Abstract

Regulation of renal Na+ transport is essential for controlling blood pressure, as well as Na+ and K+ homeostasis. Aldosterone stimulates Na+ reabsorption by the Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC) in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) and by the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in the late DCT, connecting tubule, and collecting duct. Aldosterone increases ENaC expression by inhibiting the channel's ubiquitylation and degradation; aldosterone promotes serum-glucocorticoid-regulated kinase SGK1-mediated phosphorylation of the ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4-2 on serine 328, which prevents the Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction. It is important to note that aldosterone increases NCC protein expression by an unknown post-translational mechanism. Here, we present evidence that Nedd4-2 coimmunoprecipitated with NCC and stimulated NCC ubiquitylation at the surface of transfected HEK293 cells. In Xenopus laevis oocytes, coexpression of NCC with wild-type Nedd4-2, but not its catalytically inactive mutant, strongly decreased NCC activity and surface expression. SGK1 prevented this inhibition in a kinase-dependent manner. Furthermore, deficiency of Nedd4-2 in the renal tubules of mice and in cultured mDCT15 cells upregulated NCC. In contrast to ENaC, Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of NCC did not require the PY-like motif of NCC. Moreover, the mutation of Nedd4-2 at either serine 328 or 222 did not affect SGK1 action, and mutation at both sites enhanced Nedd4-2 activity and abolished SGK1-dependent inhibition. Taken together, these results suggest that aldosterone modulates NCC protein expression via a pathway involving SGK1 and Nedd4-2 and provides an explanation for the well-known aldosterone-induced increase in NCC protein expression.

The mineralocorticoid hormone aldosterone plays an important role in controlling Na+ and K+ balance by enhancing Na+ reabsorption or K+ secretion in the kidney. Aldosterone acts on the so-called aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (ASDN), which is defined by the coexpression of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC), the mineralocorticoid receptor, the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, which prevents illicit occupation of mineralocorticoid receptor by glucocorticoids, and the serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), which is a primary transducer of the aldosterone message.1–5 The ASDN lies distal to the macula densa and comprises the late part of the distal convoluted tubule (DCT2), the connecting tubule, and the collecting duct. In the ASDN Na+ is reabsorbed at the apical membrane by the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl−-cotransporter (NCC), expressed in DCT1 and DCT2,6 and by ENaC, expressed in DCT2, the connecting tubule, and the collecting duct.6 The Na+-K+-ATPase, expressed at the basolateral membrane, provides the electrochemical gradient for both Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion.7 K+ is secreted at the apical membrane by the inwardly-rectifying K+ channel (ROMK)8 and by the flow-dependent maxi-K+ channel.9

Aldosterone modulates the expression and activity of these transporters. ENaC's regulation by aldosterone has been well described and involves increased expression of SGK1, which then phosphorylates the ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4-2 (neuronal precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein) on serine 328 (S328), thereby inhibiting Nedd4-2-induced ENaC ubiquitylation and degradation.10–15 The importance of this post-translational ENaC regulation is illustrated in Liddle's syndrome, which is caused by mutations in PY (PPXY, where P is proline, Y is tyrosine, and X is any amino acid) motifs in the β- or γ-ENaC subunits, normally required for the Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction, thus leading to ENaC overactivation.11,16–18

Less is known about the molecular mechanisms involved in NCC regulation by aldosterone. It has been shown that aldosterone increases NCC expression by a post-translational mechanism, because the increased NCC protein levels, which are seen in experimental models of hyperaldosteronism, are not preceded or accompanied by an increase in NCC mRNA levels.19–22 It is known that aldosterone's effects in the ASDN are transduced by activation of the SGK1 kinase, which is only expressed in this part of the kidney.23–25 Recently, it has been suggested that SGK1 could increase NCC activity by phosphorylating WNK4 and thus preventing the WNK4-induced inhibition of the cotransporter.26

The coexpression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, SGK1, Nedd4-2, and NCC in DCT2 suggests that the post-translational increase of NCC induced by aldosterone could be explained through a mechanism involving SGK1 and Nedd4-2. Here, we present evidence that Nedd4-2 is a negative regulator of NCC and that its effect on the cotransporter is inhibited by SGK1 in a kinase-dependent fashion. In vivo observations in Nedd4-2 knockout mice corroborate our biochemical and functional findings. We propose that activation of the SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway is an important mechanism for regulation of NCC activity during high aldosterone states.

RESULTS

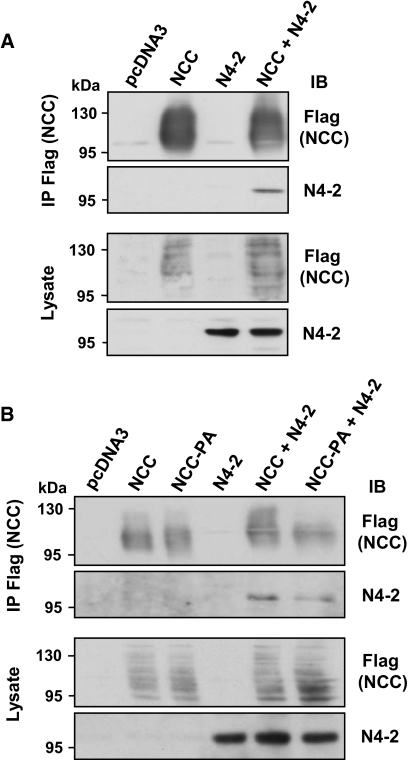

Nedd4-2 Interacts with NCC Independently of a PY Motif in NCC

Previously, it has been shown that interaction between ENaC and Nedd4-2 is required for ENaC internalization. To test whether Nedd4-2 could also be involved in the regulation of NCC, we investigated whether NCC interacts with Nedd4-2. HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged NCC with or without Nedd4-2 (Figure 1A). Coimmunoprecipitation of NCC with Nedd4-2 demonstrated that both proteins interact. Because Nedd4-2 has been shown to bind via its WW domains to PY motifs of target proteins (such as ENaC),12 we searched for PY motifs (PPXY) in the human NCC protein sequence and identified a PY-like motif (843… TLLIPYLLGR… 852) within the intracellular C terminus. Immunoprecipitations between NCC and Nedd4-2 were carried out using a mutated NCC, in which the proline of the PY-like motif was replaced by an alanine (NCC-P847A) (Figure 1B). Results show that the mutation in the PY-like motif did not prevent the interaction between NCC and Nedd4-2, suggesting that NCC interacts with Nedd4-2 independently of this motif.

Figure 1.

Nedd4-2 interacts with Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC) independently of a PY-like motif in the cotransporter. HEK293 cells were transfected with wild-type Flag-tagged NCC (A) or with NCC-P847A, mutated in the PY-like motif (NCC-PA) (B) with or without Nedd4-2 (N4-2), as indicated. Immunoprecipitation was performed on cell lysates using an anti-Flag (NCC) antibody. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated. The blots are representative of three independent experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

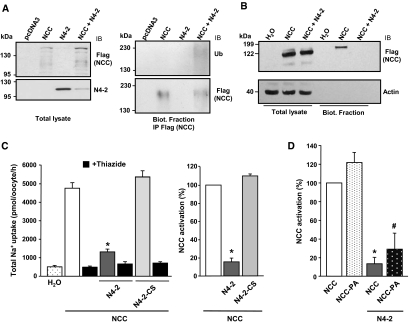

Nedd4-2 Downregulates Cell-Surface NCC Expression and Function via Ubiquitylation

Nedd4-2 has been shown to ubiquitylate and decrease the activity of several ion channels and transport proteins by inducing their ubiquitylation and degradation.13 To test whether Nedd4-2 ubiquitylates NCC at the cell surface, Nedd4-2 and Flag-tagged NCC were coexpressed in HEK293 cells. When coexpressed with Nedd4-2, NCC becomes ubiquitylated at the cell surface, and its surface expression is decreased, but not in the total lysate (Figure 2A, compare left and right panels). Interestingly, whereas the bulk of total NCC in the lysates migrated at an apparent molecular mass of 110 to 120 kD (Figures 1 and 2), the biotinylated NCC migrated at approximately 180 kD, and on the anti-ubiquitin blot, a smear appeared at around 230 kD exclusively when NCC and Nedd4-2 were coexpressed (Figure 2A, right upper panel). Our data suggest that cell-surface NCC is modified with 5 to 6 ubiquitin polypeptides, thus explaining the observed difference in apparent molecular mass (50 kD). The different molecular masses observed for NCC in the lysates versus immunoprecipitations possibly represent differences between not mature and mature NCC forms.27

Figure 2.

Nedd4-2 down-regulates NCC cell-surface expression and function via ubiquitylation. (A) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Flag-NCC with or without Nedd4-2 (N4-2). Surface proteins were labeled with biotin and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag (NCC). Biotinylated NCC was then captured using streptavidin-sepharose beads, and the precipitated material was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Flag (NCC) or anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibodies. The blot is representative of the results obtained from two independent experiments. (B) Oocytes were injected with H2O, Flag-NCC alone or with Nedd4-2 (N4-2). Surface proteins were labeled with biotin and precipitated with streptavidin-agarose beads. Total lysates and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Flag (NCC) or anti-actin. This blot is representative of four independent experiments. (C) NCC function was assessed as the [22Na+] uptake in the absence or presence (black bars) of thiazide (100 μM) in X. laevis oocytes injected with NCC cRNA with or without Nedd4-2 wild-type (N4-2) or the catalytically inactive Nedd4-2-CS cRNA (N4-2-CS), as stated (data represents the pool of 13 experiments). The graph on the left shows the results in pmol/oocyte/h, and the graph on the right depicts the NCC activation in percentage, taking as 100% the thiazide-sensitive Na+ uptake in oocytes injected with NCC alone. NCC basal function was markedly decreased when coinjected with Nedd4-2, but not with the catalytically inactive Nedd4-2-CS. (D) The effect of Nedd4-2 was assessed on wild-type NCC and NCC lacking the PY-like motif (NCC-PA). Activity in oocytes injected with NCC alone was taken as 100%. No difference was observed in basal activity or in response to Nedd4-2 between NCC wild-type and NCC-PA variant. *P < 0.001 versus NCC alone; #P < 0.01 versus NCC-PA variant alone. NCC, Na+-Cl− cotransporter; IB, immunoblot.

Because the HEK293 cells represent a heterologous expression system that may not accurately recapitulate the physiologic situation, we aimed to support the biochemical data in these cells, with three other systems, including the Xenopus laevis oocytes. We tested the effect of Nedd4-2 on NCC function by measuring the thiazide-sensitive [22Na+] uptake. As described previously,28 Xenopus oocytes microinjected with NCC cRNA exhibited an increased Na+ uptake up to 4770 ± 279 pmol/oocyte/h that was completely abolished by thiazide (Figure 2C). The NCC-induced increase in Na+ uptake was reduced by 85% when coinjected with Nedd4-2 cRNA (1310 ± 155 pmol/oocyte/h, P < 0.01 versus no Nedd4-2). These effects did not occur in the presence of the catalytically inactive Nedd4-2-C822S (N4-2-CS) mutant, suggesting that the effect of Nedd4-2 on NCC is dependent on an ubiquitylation process, similar to what was described previously for ENaC.29 Cell-surface biotinylation experiments were carried out in the oocytes and showed that Nedd4-2 completely abolished cell-surface expression of NCC (Figure 2B). Additionally, as shown in Figure 2D, the PY-like motif present in NCC was not required for the negative effect of Nedd4-2 on NCC, because the NCC-P847A mutant, where the PY-like motif was mutated, was similarly down-regulated by Nedd4-2. These observations corroborate the experiments done in HEK293 cells, in which the PY-like motif was not required for Nedd4-2/NCC interaction (Figure 1B).

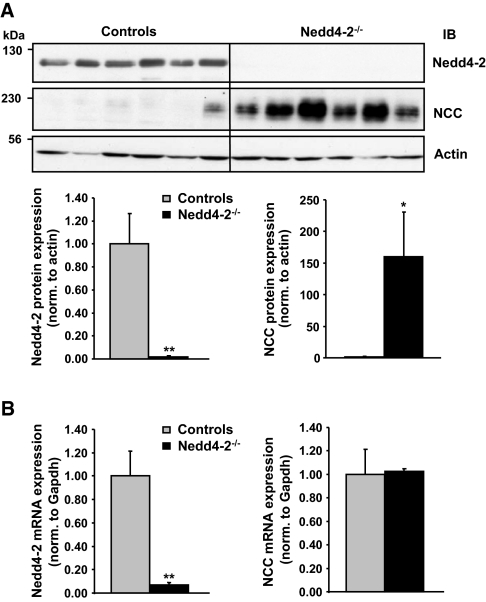

Loss of Nedd4-2 Protein in Vivo Leads to a Striking Increase in NCC Expression

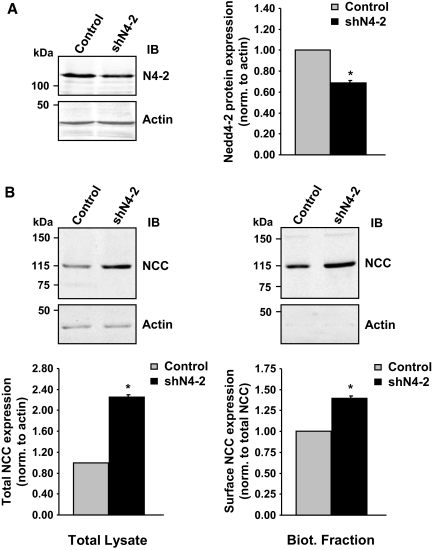

To provide in vivo corroboration of the data observed in HEK293 cells and Xenopus oocytes, we took advantage of an inducible renal tubule-specific Nedd4-2 knockout mouse model that we had recently generated. Mice homozygous for the Nedd4-2 floxed allele18 and double transgenic for Pax8-rTA and TRE-LC130 were treated with doxycycline to induce renal tubule-specific Cre-mediated recombination and thereby Nedd4-2 inactivation (Figure 3). Loss of renal Nedd4-2 protein in doxycycline-induced mutants led to an increase in ENaC protein expression, as previously shown in a total Nedd4-2 knockout model (Supplementary Figure S1), despite low plasma aldosterone levels in the mutant. Similarly, we observed a strong increase in NCC protein expression (Figure 3A) without any change in NCC mRNA levels (Figure 3B), suggesting that Nedd4-2 is controlling NCC expression at the post-translational level. To determine whether the effect of Nedd4-2 suppression on NCC was a cellular and not an indirect physiologic effect, we carried out RNA interference experiments in a cell line derived from mouse DCT (mDCT15 cells). Lentiviral infection of a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) construct directed against Nedd4-2 caused a reduction of 40% of the Nedd4-2 protein as compared with a control construct (Figure 4A). This reduction of Nedd4-2 was accompanied by an increase of total and cell-surface NCC protein, as evidenced in whole cell lysates and in cell-surface biotinylated fraction (Figure 4B). These data confirm that Nedd4-2 is crucial for down-regulating NCC protein expression in vivo.

Figure 3.

Loss of Nedd4-2 protein in vivo leads to increase in NCC protein expression but unchanged mRNA levels, suggesting a post-translational regulation of the cotransporter. (A) Inducible renal tubule-specific Nedd4-2Pax8/LC1 knockout mice (Nedd4-2−/−) and Nedd4-2Pax8 or Nedd4-2LC1 control littermates (controls) were treated with doxycycline and challenged with high-Na+ diet. Total kidney lysates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated (Nedd4-2−/−, n = 6; controls, n = 6). Graphs show quantification of Nedd4-2 and NCC protein expression in controls and induced Nedd4-2−/− mice in two independent experiments (Nedd4-2−/−, n = 9; controls, n = 12). Protein expression is expressed relative to control values and normalized to the amount of actin. (B) Nedd4-2 and NCC mRNA expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR in controls (n = 7) and induced Nedd4-2−/− mice (n = 11). mRNA expression is expressed relative to control values and normalized to the expression of GAPDH mRNA. NCC mRNA levels were unchanged between controls and induced Nedd4-2−/− mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus controls. NCC, Na+-Cl− cotransporter; IB, immunoblot.

Figure 4.

RNA interference of Nedd4-2 causes increased NCC expression. (A) mDCT15 cells were infected with a lentiviral shRNA construct specific for Nedd4-2 (shN4-2) or a control construct. Lysates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated. The accompanying graphs show quantification of Nedd4-2 (N4-2) protein expression by densitometry, demonstrating a reduction in Nedd4-2 expression with shN4-2 infection. Protein expression is expressed relative to control values and normalized to the amount of actin. A representative blot of four independent experiments is shown. (B) mDCT15 cells infected as above were treated with cell-impermeable biotin, with resulting lysates undergoing streptavidin pull-down to obtain biotinylated (cell surface expressed) fractions. Lysates and cell-surface fractions were analyzed by Western blot as indicated. The accompanying graphs show quantification of NCC protein expression by densitometry, demonstrating an increase in NCC expression with decreased Nedd4-2 expression. Protein expression is indicated relative to control values and normalized to the amount of actin for total NCC and to the amount of normalized total NCC for surface expressed NCC (biotinylated fraction). A representative blot of four independent experiments is shown. *P < 0.05. NCC, Na+-Cl− cotransporter; IB, immunoblot.

SGK1 Interacts with NCC and Prevents Nedd4-2-mediated Inhibition of the Cotransporter in a Kinase-dependent Manner

SGK1 has been shown to increase ENaC activity by phosphorylating Nedd4-2, thereby preventing the Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction and degradation of the channel.10,14 To test the hypothesis that SGK1 may also be involved in the Nedd4-2-dependent NCC regulation,26,31 we investigated first whether SGK1 could interact with NCC. HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-NCC with or without the constitutively active SGK1-S422D (SGK1-SD) mutant (Figure 5A). Using an anti-Flag (NCC) antibody, we found that SGK1 coimmunoprecipitates with NCC. As described previously for the Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction,10,14 the effect of SGK1 on Nedd4-2/NCC interaction was then investigated in HEK293 cells transfected with NCC, Nedd4-2, and SGK1. Our data revealed that coimmunoprecipitation between Nedd4-2 and NCC was reduced when both proteins were coexpressed with the constitutively active SGK1-S422D mutant, but not when coexpressed with the inactive SGK1-K127A (SGK1-KA) mutant (Figure 5B), indicating that SGK1 interferes with the Nedd4-2/NCC interaction in a kinase-dependent manner. To confirm the relevance of this result at the functional level, thiazide-sensitive [22Na+]uptake was measured in Xenopus oocytes injected with NCC cRNA alone or in the presence of Nedd4-2 cRNA, SGK1 cRNA, or both. As shown in Figure 4C, injection of Nedd4-2 cRNA resulted in a marked decrease in NCC activity. This inhibition was completely abolished by coexpression with the constitutively active SGK1-S422D (SGK1-SD) and was dependent on SGK1 kinase activity, because the catalytically inactive mutant SGK1-K127A (SGK1-KA) had no effect on Nedd4-2-induced NCC inhibition (Figure 5C). Taken together, these data show that SGK1 interacts with NCC, reduces Nedd4-2/NCC interaction, and prevents Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of NCC activity in a kinase-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

SGK1 prevents Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of NCC in a kinase-dependent manner. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-NCC with or without constitutively active SGK1-S422D (SGK1-SD). NCC was immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated, demonstrating that SGK1 and NCC interact. A representative blot of three independent experiments is shown. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-NCC alone, with Nedd4-2 (N4-2), or with SGK1-SD or the SGK1-K127A kinase-dead mutant (SGK1-KA). NCC was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using an anti-Flag. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated. SGK1 was able to abrogate interaction between NCC and Nedd4-2 in a kinase-dependent manner. (C) NCC function in X. laevis oocytes was assessed as total Na+ uptake in pmol/oocyte/h (left graph) and as NCC activation in percentage versus control (right graph) in the absence or presence (black bars) of thiazide (100 μM). NCC was inhibited by coinjection with Nedd4-2 cRNA (100% versus 32%). This effect was abrogated in the presence of the constitutively active SGK1-SD mutant, but not the kinase-dead SGK1-KA mutant (100% versus 41%). *P < 0.01 versus NCC. NCC, Na+-Cl− cotransporter; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

SGK1 Regulates Nedd4-2-dependent Inhibition by Direct Phosphorylation

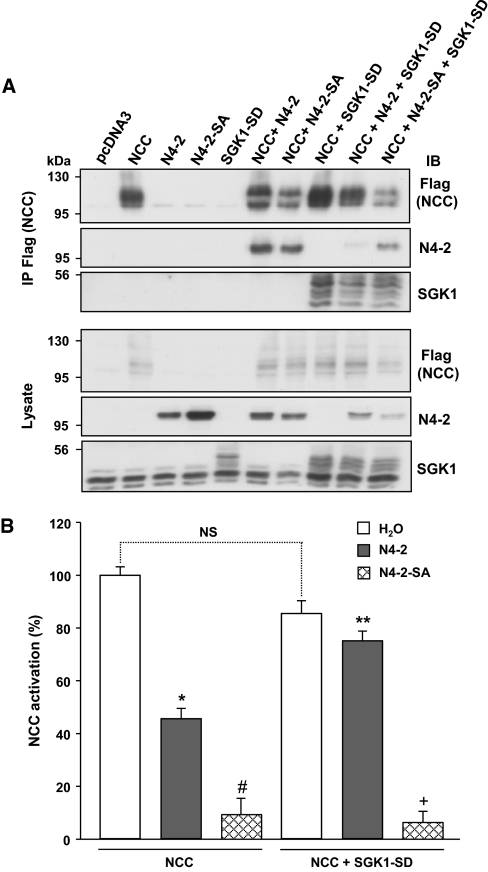

It has been previously shown that, to interfere with Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction, SGK1 phosphorylates Nedd4-2 primarily on S328 and to a lesser extent on S222.14 To test whether SGK1 regulates NCC by phosphorylating Nedd4-2 on the same sites as for ENaC, we carried out experiments in which we mutated either S328 or S222 to alanine and performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments in HEK293 cells and functional assays in Xenopus oocytes. Coimmunoprecipitation in HEK293 cells did not yield to consistent data (not shown). However, in contrast to what has been shown for the regulation of ENaC, we observed that Nedd4-2-S328A inhibits NCC by 76 ± 4% and by only 37 ± 5% in the presence of SGK1. In contrast, Nedd4-2-S222A inhibits NCC by 44 ± 5.6%, and intriguingly, this inhibition was further increased to 67 ± 6% in the presence of SGK1. These results suggest that neither S222 nor S328 is critical by itself for the regulation of NCC. Because Nedd4-2 can be phosphorylated on these sites by numerous different kinases,32 we reasoned that there may be differential phosphorylations by endogenous kinases varying from batch to batch of oocytes or HEK293 cells, to which the regulation of NCC might be more susceptible than ENaC. We therefore generated a double mutant Nedd4-2-S222,328A (N4-2-SA) and cotransfected HEK293 cells with either wild-type or Nedd4-2 double mutant, NCC and SGK1. Immunoprecipitation of NCC revealed that both wild-type Nedd4-2 and N4-2-SA interacted with NCC (Figure 6A). When SGK1 was coexpressed, coimmunoprecipitation of wild-type Nedd4-2 and NCC was reduced, as shown in Figure 5A, whereas SGK1 had no effect on the interaction between the double mutant N4-2-SA and NCC. These data suggest that SGK1 acts via phosphorylation of both S222 and S328. To confirm these findings, we carried out functional experiments in X. laevis oocytes measuring thiazide-sensitive [22Na+] uptake. Similarly to what was observed in HEK293 cells, we found that both wild-type Nedd4-2 and the double mutant, to a stronger extent, were able to inhibit NCC activity (Figure 6B). Moreover, SGK1 only reversed the inhibition by wild-type Nedd4-2 and not by the double mutant. These results imply that NCC is inhibited by Nedd4-2 and that SGK1 interferes with this inhibition possibly by directly phosphorylating Nedd4-2 on both S222 and S328.

Figure 6.

Nedd4-2-mediated NCC regulation by SGK1 involves Nedd4-2 phosphorylation on both S222 and S328. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-NCC alone, with Nedd4-2 (N4-2), or the Nedd4-2-S222,328A (N4-2-SA), and with or without constitutively active SGK1 mutant (SGK1-SD), as indicated. NCC was immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag antibody. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot as indicated. The blot is representative of the results obtained from three independent experiments. (B) NCC function was assessed as the [22Na+] uptake in the absence or presence of thiazide (100 μM) in X. laevis oocytes injected with NCC with or without wild-type Nedd4-2 (N4-2) or the double mutant Nedd4-2-SA (N4-2-SA), with or without the constitutively active SGK1 (SGK1-SD), as indicated. SGK1 was able to recover inhibition by wild-type N4-2 but not by N4-2-SA, which in turn inhibited NCC more efficiently than the wild-type variant. The results of five different experiments, expressed as percentages of activity, taking the uptake in NCC control group as 100%. *P < 0.001 versus NCC, #P < 0.001 versus NCC, **P < 0.0001 versus NCC+N4-2, +P < 0.001 versus NCC+SGK1. NCC, Na+-Cl− cotransporter; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms by which aldosterone promotes a post-translational increase in NCC protein levels have long remained elusive. WNK4 has been proposed to be an important player behind aldosterone's actions on ENaC, NCC, and ROMK.33–38 It has been shown that NCC protein expression is increased under aldosterone secretion, without changes in NCC mRNA levels, suggesting a post-translational modification of the cotransporter.19–22 In the case of ENaC, SGK1 phosphorylates the ubiquitin-protein ligase Nedd4-2 and prevents the ENaC/Nedd4-2 interaction, ubiquitylation, and degradation of the channel and thus increases ENaC-mediated Na+ reabsorption.14,15 This mechanism explains, at least in part, how aldosterone secretion is associated with increased ENaC protein levels.

Here, we show both in vitro and in vivo that Nedd4-2 regulates NCC. Using transfected HEK293 cells, we demonstrate that Nedd4-2 interacts with NCC in a PY motif-independent manner (Figure 1, A and B), in contrast to ENaC.12 In addition, we show that Nedd4-2 induces ubiquitylation of the cotransporter at the cell surface (Figure 2A). It was previously shown that NCC resides at the apical membrane, as well as in subapical vesicles, and that NCC is redistributed to the cell surface in response to angiotensin II.39 However, it was not clear whether this was due to an increase in NCC exocytosis to the cell surface or a decrease in NCC endocytosis. Our findings establish that cell-surface (biotinylated) NCC is ubiquitylated by Nedd4-2. These results reinforce recent data from Ko et al.,40 who recently showed that NCC is ubiquitylated under Ras-GRP1 stimulation via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in mDCT cells, leading to endocytosis and decreased NCC activity. Other groups have suggested that WNK4 is involved in the inhibition of NCC forward trafficking.26 However, they did not show that phosphorylation of NCC is necessary for the WNK4 inhibitory effect. It is possible that acute phosphorylation of the cotransporter (presumably by SPAK) involves an increase in the transporter activity without any increase in surface expression.41,42 Some other studies have shown that increased activity of NCC by phosphorylation stimuli is associated with increased trafficking toward the plasma membrane,43,44 and more recent papers suggested that sodium and potassium diets regulate NCC surface expression.45,46 It is therefore not clear whether phosphorylation occurs before or after trafficking to the cell surface.47 One hypothesis would be that surface-expressed NCC could be a better substrate for phosphorylation and that phosphorylation would not cause the translocation.

Our biochemical observations are corroborated by functional studies in X. laevis oocytes. Indeed, coinjection of NCC with wild-type Nedd4-2, but not the catalytically inactive mutant, dramatically decreased NCC activity (Figure 2C). Moreover, we find that silencing Nedd4-2 by RNA interference in mDCT15 cells leads to an increase of NCC protein both in whole cell lysates and at the cell surface (Figure 4). Importantly, in vivo experiments confirmed that NCC expression is highly up-regulated in inducible renal tubule-specific Nedd4-2 knockout mice versus control littermates (Figure 3), despite decreased plasma aldosterone (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore, this regulation takes place at the post-translational level, because NCC mRNA is not affected in these mice (Figure 3B). This increase in NCC protein expression is not observed in a constitutive Nedd4-2 total knockout mouse model, or at least it did not reach significance.18 It is possible that in the constitutive knockout mice, where Nedd4-2 has been inactivated already during development, compensatory mechanisms have taken place and have led to adaptation, activating other pathways to decrease NCC. Our inducible Nedd4-2 knockout model would lack the adaptation because the mutation has been induced a few days before the protein expression was analyzed. Thus, both in vitro and in vivo observations point to Nedd4-2 as a key regulator of NCC.

In addition, we found that SGK1 coimmunoprecipitates with NCC (Figure 5A) and prevents, in a kinase-dependent fashion, Nedd4-2/NCC interaction in HEK293 cells and Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of NCC activity in X. laevis oocytes (Figure 5 B and C). These observations are supported by in vivo data from previously published SGK1 total knockout mice, which displayed decreased expression of total NCC.31 Impaired up-regulation of NCC expression in SGK1 knockout mice are most likely contributing to the renal Na+-losing phenotype under dietary Na+ restriction. Taken together, these data suggest that the SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway is involved in NCC regulation and may contribute to the aldosterone-mediated increase of NCC protein expression without altering NCC mRNA levels. These novel findings complement what has been already shown for numerous channels and transporters that are regulated by either SGK1 or Nedd4-2 or both, including the voltage-gated Na+ channels SCN5A,48 the voltage-gated K+ channels Kv1.5,49 KCNQ1,50 the Cl− channels ClCKa/Barttin,51 the intestinal phosphate cotransporter NaPi IIb,52 connexin 43,53 and many other transporters.54

Interestingly, we obtained evidence for differential regulation of NCC and ENaC by the SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway. Our data suggest that the NCC regulation via Nedd4-2 is probably indirect, because it does not depend on a PY motif in NCC. This is in contrast with what has been shown for the Nedd4-2-mediated regulation of ENaC, and a number of other membrane proteins,55 which require PY motifs.12 It is known that Nedd4 and Nedd4-like proteins can bind to target proteins that do not contain any PY motif, using adaptors that contain PY motifs themselves.56–58 Further work will be required to establish whether the interaction between NCC and Nedd4-2 is direct or occurs via such adaptors and, in this case, to find the involved adaptor. However, the fact that the Nedd4-2's effect on NCC is independent of a PY motif in the cotransporter provides evidence that Nedd4-2-mediated ubiquitylation of NCC and ENaC occurs by different mechanisms and is thus susceptible for differential regulation. It has been previously shown that Nedd4-2-specific phosphorylation on S328 by SGK1 is needed for the kinase to prevent the Nedd4-2/ENaC interaction and thus the ubiquitylation of the channel.10,14 In this work, mutation to alanine of neither S328 nor S222 provided conclusive evidence with respect to interference with SGK1-dependent regulation of Nedd4-2. However, the simultaneous mutation of these two serines to alanine yielded stronger inhibition of NCC activity, and SGK1 was no longer able to abrogate the Nedd4-2/NCC interaction and the Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of the cotransporter activity (Figure 6). This suggests that, in contrast to ENaC, both Nedd4-2 sites have to be phosphorylated in order for SGK1 to interfere with Nedd4-2-dependent inhibition of NCC. During this study, we noticed that wild-type Nedd4-2 decreased NCC activity in every single experiment, but the percentage of inhibition varied from 50 to 90%. In contrast, the double Nedd4-2 mutant reduced NCC activity by more than 90% in every single experiment, suggesting that there might be variable phosphorylation of these sites by endogenous kinases. Indeed, it is well known that these phosphorylation sites on Nedd4-2 are not only targets of SGK1, but also of a number of other kinases such as PKA, Akt, GRK2, or IκB kinase β,15,59,60 which may explain the variation between different batches of oocytes.

Taken together, these results point to a dissimilar regulatory mechanism between ENaC and NCC by the SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway. Whereas phosphorylation of S328 alone interferes with the Nedd4-2 action on ENaC, our data suggest that phosphorylation of either S222 or S328 alone is not sufficient for the prevention of Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of NCC by SGK1 and that phosphorylation on both sites is necessary to intervene with SGK1 action. Hence, such differential phosphorylation may contribute to the physiologic regulation of NCC and ENaC. During hyperkalemia, increased salt delivery in the distal nephron (NCC inhibition) is required to allow the proper Na+ and K+ exchange (ENaC activation together with ROMK/BK activation). In this case, Nedd4-2 may be phosphorylated on S328, thereby inhibiting NCC, but not ENaC. However, during hypovolemia, when salt needs to be reabsorbed via NCC and possibly also ENaC, Nedd4-2 could presumably be phosphorylated on both sites. Further studies will be necessary to clarify this issue.

In conclusion, our work has identified Nedd4-2 as a new regulator of NCC. In contrast to ENaC, the Nedd4-2-mediated regulation of NCC is independent of a PY motif in NCC. Our data provide evidence that NCC and ENaC are regulated by different mechanisms and are thus susceptible for differential regulation. We showed that phosphorylation of Nedd4-2-S328 by SGK1, needed to abrogate Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of ENaC, is not sufficient for the regulation of NCC, because phosphorylation on S222 is also required. These results further suggest that under aldosterone stimulus NCC and ENaC would be regulated through a differential mechanism in DCT2. How the WNK-SPAK/OSR1-NCC and the novel SGK1-Nedd4-2-NCC pathways interact with each other in the regulation of Na+ and K+ homeostasis are important questions for future investigations.

CONCISE METHODS

cDNA Constructs

Used in HEK293 Cells.

pCMV5 comprising Flag-tagged human NCC was kindly provided by Dr. D. Alessi (Dundee, UK).37 A PY-like motif mutant NCC-P847A (NCC-PA) was generated by site-directed PCR-based mutagenesis. The cDNA from human wild-type and catalytically inactive mutant Nedd4-2-C822S (Nedd4-2-CS) have been described previously.61 The constitutively active mouse SGK1-S422D (SGK1-SD) construct was kindly provided by Dr. D. Pearce (San Francisco, CA) and described previously.62 A catalytically inactive mouse SGK1 cloned into pcDNA3 and tagged with a T7 epitope and a kinase-dead mouse mutant SGK1-K127A (SGK1-KA) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Stratagene) was applied to generate the double mutant Nedd4-2-S222,328A (N4-2-SA).

Used in X. laevis Oocytes.

NCC and Nedd4-2 cDNA constructs were described previously.14,63 Clones for the wild-type SGK1, the kinase-dead mutant (SGK1-KA), and the constitutively active mutant SGK1-SD were kindly provided by Dr. R. Lifton (Yale).64 Site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Stratagene) was performed with custom-made primers (Sigma) to obtain the rat mutant NCC-P847A (NCC-PA), the mouse Nedd4-2-S222A, Nedd4-2-S328A, and the double mutant Nedd4-2-S222,328A. All of the mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. cRNAs generated for microinjection were made by in vitro transcription utilizing mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion).

HEK293 Cell Studies

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HEK293 cells were cultured at 37°C/5% CO2 in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 0.05 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were transiently transfected in 10-cm dishes at 60% confluence using the calcium phosphate method.65

Ubiquitylation of Cell-Surface Proteins.

Cell-surface proteins were labeled by surface biotinylation as described previously for ENaC.65 Briefly, immunoprecipitation with an anti-Flag antibody was done after cell lysis, and the biotinylated fraction of NCC was recovered with streptavidin-agarose. The immunoprecipitated material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blotting with either anti-ubiquitin (Enzo Life Sciences) or anti-Flag antibodies (Sigma).

Western Blots.

Western blots were carried out as described previously.65 NCC was detected using an anti-Flag antibody (1:500, Sigma). Anti-Nedd4-2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-SGK1 (Sigma), and anti-actin (Sigma) were diluted 1:500, 1:1000, and 1:1000 for immunoblots, respectively. Secondary antibodies coupled with horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare) were used diluted 1:25,000, and Western blots were revealed with ECL reagents (GE Healthcare or Pierce, Rockford, IL).

mDCT15 Cell Studies

Generation of mDCT15 Cells.

mDCT cells (gift from Dr. P. Friedman)66 were dilutely plated and single colonies isolated via cloning rings. Individual clones were screened for NCC mRNA expression using real-time PCR and for NCC activity determined via [22Na+] uptake as described above. Clone number 15 (mDCT15) was selected for its robust NCC activity. For experiments, mDCT15 cells were plated on cell culture dishes and grown in growth medium containing a 50:50 mix of DMEM/F12, 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/neomycin, at 37°C. Experiments were conducted when the cells reached 90 to 95% confluence.

Lentiviral Transduction.

mDCT15 cells cultured as above were plated in a 96-well microtest tissue culture plate at a density of 2.5 × 103/well. At 24 hours after plating, hexadimethrine bromide was added to the medium at a final concentration of 8 μg/ml, and the cells were transduced with human GIPZ Nedd4-2 construct (V2LHS_80459) or control nontargeting shRNA (RHS-4348) (Open Biosystems). Medium containing viral particles was removed the following day and replaced with medium containing puromycin at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Medium was aspirated every 3 days and replaced with fresh puromycin-containing medium for 1 week.

Cell-Surface Biotinylation.

mDCT15 cells were incubated as above. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and cell-surface proteins were labeled with Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS for 30 minutes at 4°C. The reaction was quenched by adding 500 μl of the quenching solution (Pierce). The cells were harvested, lysed using lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor, and homogenized by sonication on ice. The cell lysates were centrifuged briefly, and supernatant was collected. 80 μl of the supernatant from each group was stored separately at −80°C. Biotinylated proteins in the cell lysates were isolated by incubating with NeutrAvidin gel (Pierce) for 60 minutes at room temperature. The labeled proteins were eluted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 50 mM dithiothreitol. Protein concentrations were determined using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce).

Generation of Anti-NCC Polyclonal Antibody.

An NCC amino-terminal peptide sequence (PGEPRKVRPTLADLHSFLKQEGC) was provided to Pocono Rabbit Farms and Laboratory for antigen generation. The peptide was generated, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin, and injected into rabbits according to their protocol. Sequential bleeds were screened by ELISA, yielding an appropriate serum sample. The serum was then affinity purified utilizing a column with the immunizing peptide. Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry were done to confirm the specificity of the immunopurified antibody.

Immunoblotting

The eluted biotinylated proteins and the cell lysates were immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-NCC antibody. For each experimental group, 80 μg of total protein from cell lysate was loaded along with 30 μl of biotinylated protein from the control group and the proportionate volume from the rest of the biotinylated protein groups. Proteins were transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 3% BSA, the membranes were probed with corresponding primary antibodies (NCC 1:1000 diluted, actin 1:200 diluted) overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed in TBST. Signal detection for NCC and actin was done using IRDye800 goat anti-mouse IgG antibody and IRDye800 rabbit anti-goat IgG antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals; dilution 1:10,000) and subsequent scanning of the membrane by the Odyssey Infrared Imager. Intensity of the protein bands was analyzed by using Odyssey Infrared Imaging Software (Li-Cor Biosciences).

X. laevis Oocyte Studies

Assessment of NCC Function.

NCC activity was assessed utilizing X. laevis oocytes as a functional expression system as described previously.28,63,67 Oocytes were injected with 10 ng of wild-type or mutant NCC cRNA per oocyte, alone or in combination with other cRNAs expressing wild-type or mutant mNedd4-2 or SGK1, as indicated in each experiment. Seventy-two to 96 h after injection, NCC activity was assessed by measuring [22Na+] tracer uptake in the presence or absence of 100 μM thiazide. The oocytes were initially placed in a Cl−-free preincubation solution for 30 minutes and then transferred to a [22Na+]-containing uptake solution for 60 minutes. Mean [22Na+] uptake that occurred in the presence of thiazide was subtracted to the values measured in its absence to obtain the thiazide-sensitive [22Na+] uptake mediated by NCC. Percentage of NCC activation was calculated by adjusting the values to the mean value of [22Na+] uptake in NCC control group. All of the NCC function data were assessed from a minimum of three independent experiments, which contained at least 10 oocytes per group and per experiment.

Oocyte Cell-Surface Biotinylation.

As described previously,68 oocytes injected with NCC with or without Nedd4-2 cRNA were washed five times in ND-96 TEA buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 8.8, 10 mM TEA) and incubated for 30 minutes with 1.5 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo; Pierce) in ND96-TEA buffer at 4°C. The oocytes were washed five times in ND-96-TEA buffer and homogenized using a 25-gauge needle in a sucrose-based buffer (4 μl/oocyte) comprising 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.9, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The samples were then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 8000 × g, the supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was assessed utilizing the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Reagents). Streptavidin precipitation was done by adding 50 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads in 50% slurry (Upstate; Cell Signaling Solutions) to 500 μg of biotinylated proteins diluted in 1 ml of Tris-buffered saline (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Samples were rolled overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed one time with Buffer 1 (5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), twice with Buffer 2 (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4), and once with Buffer 3 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) with a 2-minute 4000 × g centrifugation between washes. After the last wash, Buffer 3 was substituted with 30 μl of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad). Protein samples were heated to 65°C for 15 minutes before separation on a 7.5% acrylamide gel.

In Vivo Studies

Animals.

Inducible renal tubule-specific Nedd4-2 knockout mice were generated by combined use of Tet-On and Cre-loxP systems. Pax8-rtTA transgenic mice, which express the reverse tetracycline-dependent transactivator (rtTA) in all proximal and distal tubules, and the entire collecting duct system of both embryonic and adult kidneys were bred with TRE-LC1 transgenic mice, which express the Cre recombinase under the control of a rtTA-response element.30 Double transgenic Pax8-rtTA/TRE-LC1 mice (Pax8/LC1), which allow doxycycline (a tetracycline analog)-inducible renal tubule-specific Cre-mediated recombination, were bred with mice homozygous for the Nedd4-2 floxed allele18 to obtain double transgenic Nedd4-2fl/fl/Pax8/LC1 mutants (Nedd4-2Pax8/LC1). Double transgenic homozygous Nedd4-2Pax8/LC1 mice (mutants) and simple transgenic homozygous Nedd4-2Pax8 or Nedd4-2LC1 littermates (controls) were treated with doxycycline (2 mg/ml in 2% sucrose drinking water) for 11 days to induce the mutation and challenged with high-Na+ (>3.2%) diet (SNIFF, Germany) for 8 days. Plasma aldosterone was measured by RIA (Coat-a-Count; Diagnostics Products Inc.).

Western Blots on Kidney Extracts.

Half mouse kidneys were homogenized using polytron at maximum speed for 30 seconds in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.27 mM sucrose, and 1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitors (Protease inhibitor cocktail, Complete; Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (100 mM NaF, 10 mM Di-Na-pyrophosphate, and 1 mM Na3VO4). Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 20,000 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were recovered, and protein concentration was assessed by the Bradford method. Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blotting. Endogenous NCC and β- and γ-ENaC were detected using the respective antibodies (kindly provided by Dr. J. Loffing, Zurich), and Nedd4-2 was detected using an anti Nedd4-2 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) all diluted 1:500 and incubated overnight. Anti-actin (Sigma) was diluted 1:1000. The blots were revealed, as described for HEK293 cell studies, and quantified.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR on Kidney Extracts.

Total RNA of half mouse kidney was extracted using a TissueLyser (Qiagen) and the RNAquous Kit (Ambion). RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed using SuperscriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and 1 μg of random hexamer primers (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 20 μl. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in replicate for each sample using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System, the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) for Nedd4-2 (Mm01258749_m1), NCC (Mm00490213_m1), and GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1) as housekeeping gene, and the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Diluted reverse-transcribed samples (total RNA of 5 ng) were amplified in a final volume of 20 μl. The amount of Nedd4-2 and NCC mRNA was normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression.

Statistics

All of the measurements are presented as mean values ± SEM and were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t test. For NCC function assessment in Xenopus oocytes, significant differences between groups were assessed by a one-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons were done using Bonferroni's correction. For mDCT15 cell data, statistical analysis was performed using the SigmaStat software package (Systat, San Jose, CA), and statistical significance was assessed using ANOVA (Holm-Sidak). A p value of less than 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bernard Rossier and Olivier Bonny as well as the members of the Staub laboratory for critically reading the manuscript. We are grateful to Marc Maillard from the Division of Nephrology of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois CHUV for the quantification of aldosterone. This work was supported in part by the Leducq Foundation Transatlantic Network on Hypertension (to O.S. and G.G.), National Institutes of Health Grants DK-64635 (to G.G.) and K08 DK081728 (to B.S.K.), El Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología Mexico Grant 59992 (to G.G.), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01 DK085097 and K08 DK070668 (to R.S.H.), Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 31003A_125422/1 (to O.S.), the NCCR-Kidney.ch (Swiss National Science Foundation, to O.S.), and funds from the Swiss Kidney Foundation (to C.R.). J.P.A. was supported by a scholarship from El Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología Mexico and is a graduate student in the Biomedical Science Ph.D. Program of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, Valderrabano V, Klausli L, Hebert SC, Rossier BC, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Kaissling B: Distribution of transcellular calcium and sodium transport pathways along mouse distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1021–F1027, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bostanjoglo M, Reeves WB, Reilly RF, Velazquez H, Robertson N, Litwack G, Morsing P, Dorup J, Bachmann S, Ellison DH, Bostonjoglo M: 11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, mineralocorticoid receptor, and thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter expression by distal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1347–1358, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reilly RF, Ellison DH: Mammalian distal tubule: Physiology, pathophysiology, and molecular anatomy. Physiol Rev 80: 277–313, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonvalet JP, Doignon I, Blot-Chabaud M, Pradelles P, Farman N: Distribution of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase along the rabbit nephron. J Clin Invest 86: 832–837, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rusvai E, Naray-Fejes-Toth A: A new isoform of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in aldosterone target cells. J Biol Chem 268: 10717–10720, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loffing J, Kaissling B: Sodium and calcium transport pathways along the mammalian distal nephron: From rabbit to human. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F628–F643, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doucet A: Function and control of Na-K-ATPase in single nephron segments of the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 34: 749–760, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu JZ, Hall AE, Peterson LN, Bienkowski MJ, Eessalu TE, Hebert SC: Localization of the ROMK protein on apical membranes of rat kidney nephron segments. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F739–F749, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Woda CB, Bragin A, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM: Flow-dependent K+ secretion in the cortical collecting duct is mediated by a maxi-K channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F786–F793, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Snyder PM, Olson DR, Thomas BC: Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase modulates Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. J Biol Chem 277: 5–8, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abriel H, Loffing J, Rebhun JF, Pratt H, Schild L, Horisberger J-D, Rotin D, Staub O: Defective regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by Nedd4 in Liddle's syndrome. J Clin Invest 103: 667–673, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staub O, Dho S, Henry PC, Correa J, Ishikawa T, McGlade J, Rotin D: WW domains of Nedd4 binds to the proline-rich PY motifs in the epithelial Na+ channel deleted in Liddle's syndrome. EMBO J 15: 2371–2380, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abriel H, Staub O: Ubiquitylation of ion channels. Physiology 20: 398–407, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Debonneville C, Flores SY, Kamynina E, Plant PJ, Tauxe C, Thomas MA, Munster C, Chraibi A, Pratt JH, Horisberger JD, Pearce D, Loffing J, Staub O: Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by Sgk1 regulates epithelial Na(+) channel cell surface expression. EMBO J 20: 7052–7059, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snyder PM, Olson DR, Kabra R, Zhou R, Steines JC: cAMP and serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) regulate the epithelial Na(+) channel through convergent phosphorylation of Nedd4-2. J Biol Chem 279: 45753–45758, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hansson JH, Nelson-Williams C, Suzuki H, Schild L, Shimkets R, Lu Y, Canessa C, Iwasaki T, Rossier B, Lifton RP: Hypertension caused by a truncated epithelial sodium channel gamma subunit: Genetic heterogeneity of Liddle syndrome. Nat Genet 11: 76–82, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shimkets RA, Warnock DG, Bositis CM, Nelson-Williamns C, Hansson JH, Schambelan M, Gill JR, Ulick S, Milora RV, Findling JW, Canessa CM, Rossier BC, Lifton RP: Liddle's syndrome: Heritable human hypertension caused by mutations in the beta subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. Cell 79: 407–414, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi PP, Cao XR, Sweezer EM, Kinney TS, Williams NR, Husted RF, Nair R, Weiss RM, Williamson RA, Sigmund CD, Snyder PM, Staub O, Stokes JB, Yang B: Salt-sensitive hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in mice deficient in the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F462–F470, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim G-H, Masilamani S, Turner R, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA: The thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter is an aldosterone-induced protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14552–14557, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knepper MA, Brooks HL: Regulation of the sodium transporters NHE3, NKCC2 and NCC in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 10: 655–659, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abdallah JG, Schrier RW, Edelstein C, Jennings SD, Wyse B, Ellison DH: Loop diuretic infusion increases thiazide-sensitive Na+/Cl− cotransporter abundance: Role of aldosterone. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1335–1341, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moreno G, Merino A, Mercado A, Herrera JP, González-Salazar J, Correa-Rotter R, Hebert SC, Gamba G: Electronuetral Na-coupled cotransporter expression in the kidney during variations of NaCl and water metabolism. Hypertension 31: 1002–1006, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vallon V, Wulff P, Huang DY, Loffing J, Volkl H, Kuhl D, Lang F: Role of Sgk1 in salt and potassium homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R4–R10, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCormick JA, Bhalla V, Pao AC, Pearce D: SGK1: A rapid aldosterone-induced regulator of renal sodium reabsorption. Physiology 20: 134–139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lang F, Bohmer C, Palmada M, Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Vallon V: (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol Rev 86: 1151–1178, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rozansky DJ, Cornwall T, Subramanya AR, Rogers S, Yang YF, David LL, Zhu X, Yang CL, Ellison DH: Aldosterone mediates activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter through an SGK1 and WNK4 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest 119: 2601–2612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Jong JC, Willems PH, Mooren FJ, van den Heuvel LP, Knoers NV, Bindels RJ: The structural unit of the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter is a homodimer. J Biol Chem 278: 24302–24307, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moreno E, San Cristobal P, Rivera M, Vazquez N, Bobadilla NA, Gamba G: Affinity defining domains in the Na-Cl cotransporter: Different location for Cl− and thiazide binding. J Biol Chem 281: 17266–17275, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamynina E, Debonneville C, Bens M, Vandewalle A, Staub O: A novel mouse Nedd4 protein suppresses the activity of the epithelial Na+ channel. FASEB J 15: 204–214, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Traykova-Brauch M, Schonig K, Greiner O, Miloud T, Jauch A, Bode M, Felsher DW, Glick AB, Kwiatkowski DJ, Bujard H, Horst J, von Knebel DM, Niggli FK, Kriz W, Grone HJ, Koesters R: An efficient and versatile system for acute and chronic modulation of renal tubular function in transgenic mice. Nat Med 14: 979–984, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fejes-Toth G, Frindt G, Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Palmer LG: Epithelial Na+ channel activation and processing in mice lacking SGK1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1298–F1305, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hallows KR, Bhalla V, Oyster NM, Wijngaarden MA, Lee JK, Li H, Chandran S, Xia X, Huang Z, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL, Pearce D: Phosphopeptide screen uncovers novel phosphorylation sites of Nedd4-2 that potentiate its inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. J Biol Chem 285: 21671–21678, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kahle KT, Wilson FH, Leng Q, Lalioti MD, O'Connell AD, Dong K, Rapson AK, MacGregor GG, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP: WNK4 regulates the balance between renal NaCl reabsorption and K+ secretion. Nat Genet 35: 372–376, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. San Cristobal P, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Richardson C, Ring AM, Vazquez N, Rafiqi FH, Chari D, Kahle KT, Leng Q, Bobadilla NA, Hebert SC, Alessi DR, Lifton RP, Gamba G: Angiotensin II signaling increases activity of the renal Na-Cl cotransporter through a WNK4-SPAK-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4384–4389, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ring AM, Leng Q, Rinehart J, Wilson FH, Kahle KT, Hebert SC, Lifton RP: An SGK1 site in WNK4 regulates Na+ channel and K+ channel activity and has implications for aldosterone signaling and K+ homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 4025–4029, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gamba G: The thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter: Molecular biology, functional properties, and regulation by WNKs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F838–F848, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HK, Moleleki N, Vandewalle A, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Alessi DR: Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci 121: 675–684, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Richardson C, Alessi DR: The regulation of salt transport and blood pressure by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signalling pathway. J Cell Sci 121: 3293–3304, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sandberg MB, Riquier AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, McDonough AA, Maunsbach AB: Angiotensin II provokes acute trafficking of distal tubule NaCl cotransporter (NCC) to apical membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F662–F669, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ko B, Kamsteeg EJ, Cooke LL, Moddes LN, Deen PM, Hoover RS: RasGRP1 stimulation enhances ubiquitination and endocytosis of the sodium-chloride cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F300–F309, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pacheco-Alvarez D, San Cristobal P, Meade P, Moreno E, Vazquez N, Munoz E, Diaz A, Juarez ME, Gimenez I, Gamba G: The Na-Cl cotransporter is activated and phosphorylated at the amino terminal domain upon intracellular chloride depletion. J Biol Chem 281: 28755–28763, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pedersen NB, Hofmeister MV, Rosenbaek LL, Nielsen J, Fenton RA: Vasopressin induces phosphorylation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule. Kidney Int 78: 160–169, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rinehart J, Kahle KT, De Los Heros P, Vazquez N, Meade P, Wilson FH, Hebert SC, Gimenez I, Gamba G, Lifton RP: WNK3 kinase is a positive regulator of NKCC2 and NCC, renal cation-Cl− cotransporters required for normal blood pressure homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16777–16782, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mutig K, Saritas T, Uchida S, Kahl T, Borowski T, Paliege A, Böhlick A, Bleich M, Shan Q, Bachmann S: Short-term stimulation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+,Cl− cotransporter by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F502–F509, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Frindt G, Palmer LG: Surface expression of sodium channels and transporters in rat kidney: Effects of dietary sodium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1249–F1255, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frindt G, Palmer LG: Effects of dietary K on cell-surface expression of renal ion channels and transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F890–F897, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gamba G: The nanopeptide hormone vasopressin is a new player in the modulation of renal Na(+)-Cl(-) cotransporter activity. Kidney Int 78: 127–129, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Bemmelen MX, Rougier JS, Gavillet B, Apotheloz F, Daidie D, Tateyama M, Rivolta I, Thomas MA, Kass RS, Staub O, Abriel H: Cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 is regulated by Nedd4-2 mediated ubiquitination. Circ Res 95: 284–291, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Boehmer C, Laufer J, Jeyaraj S, Klaus F, Lindner R, Lang F, Palmada M: Modulation of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.5 by the SGK1 protein kinase involves inhibition of channel ubiquitination. Cell Physiol Biochem 22: 591–600, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jespersen T, Membrez M, Nicolas CS, Pitard B, Staub O, Olesen SP, Baro I, Abriel H: The KCNQ1 potassium channel is down-regulated by ubiquitylating enzymes of the Nedd4/Nedd4-like family. Cardiovasc Res 74: 64–74, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Embark HM, Bohmer C, Palmada M, Rajamanickam J, Wyatt AW, Wallisch S, Capasso G, Waldegger P, Seyberth HW, Waldegger S, Lang F: Regulation of CLC-Ka/barttin by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and the serum- and glucocorticoid-dependent kinases. Kidney Int 66: 1918–1925, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Palmada M, Dieter M, Speil A, Bohmer C, Mack AF, Wagner HJ, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Murer H, Biber J, Closs EI, Lang F: Regulation of intestinal phosphate cotransporter NaPi IIb by ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and by serum- and glucocorticoid-dependent kinase 1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G143–G150, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leykauf K, Salek M, Bomke J, Frech M, Lehmann WD, Durst M, Alonso A: Ubiquitin protein ligase Nedd4 binds to connexin43 by a phosphorylation-modulated process. J Cell Sci 119: 3634–3642, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rotin D, Staub O: Role of the ubiquitin system in regulating ion transport. Pflugers Arch 461: 1–21, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Staub O, Rotin D: Role of ubiquitylation in cellular membrane transport. Physiol Rev 86: 669–707, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin CH, MacGurn JA, Chu T, Stefan CJ, Emr SD: Arrestin-related ubiquitin-ligase adaptors regulate endocytosis and protein turnover at the cell surface. Cell 135: 714–725, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Howitt J, Putz U, Lackovic J, Doan A, Dorstyn L, Cheng H, Yang B, Chan-Ling T, Silke J, Kumar S, Tan SS: Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) regulation by Ndfip1 prevents metal toxicity in human neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15489–15494, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mund T, Pelham HR: Control of the activity of WW-HECT domain E3 ubiquitin ligases by NDFIP proteins. EMBO Rep 10: 501–507, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee IH, Dinudom A, Sanchez-Perez A, Kumar S, Cook DI: Akt mediates the effect of insulin on epithelial sodium channels by inhibiting Nedd4-2. J Biol Chem 282: 29866–29873, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dinudom A, Fotia AB, Lefkowitz RJ, Young JA, Kumar S, Cook DI: The kinase Grk2 regulates Nedd4/Nedd4-2-dependent control of epithelial Na+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 11886–11890, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Blot V, Perugi F, Gay B, Prevost MC, Briant L, Tangy F, Abriel H, Staub O, Dokhelar MC, Pique C: Nedd4.1-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent recruitment of Tsg101 ensure HTLV-1 Gag trafficking towards the multivesicular body pathway prior to virus budding. J Cell Sci 117: 2357–2367, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bhalla V, Daidie D, Li H, Pao AC, LaGrange LP, Wang J, Vandewalle A, Stockand JD, Staub O, Pearce D: Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 regulates ubiquitin ligase neural precursor cell-expressed, developmentally down-regulated protein 4-2 by inducing interaction with 14-3-3. Mol Endocrinol 19: 3073–3084, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gamba G, Miyanoshita A, Lombardi M, Lytton J, Lee WS, Hediger MA, Hebert SC: Molecular cloning, primary structure and characterization of two members of the mammalian electroneutral sodium-(potassium)-chloride cotransporter family expressed in kidney. J Biol Chem 269: 17713–17722, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kobayashi T, Deak M, Morrice N, Cohen P: Characterization of the structure and regulation of two novel isoforms of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase. Biochem J 344: 189–197, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ruffieux-Daidie D, Poirot O, Boulkroun S, Verrey F, Kellenberger S, Staub O: Deubiquitylation regulates activation and proteolytic cleavage of ENaC. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2170–2180, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ko B, Joshi LM, Cooke LL, Vazquez N, Musch MW, Hebert SC, Gamba G, Hoover RS: Phorbol ester stimulation of RasGRP1 regulates the sodium-chloride cotransporter by a PKC-independent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 20120–20125, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Monroy A, Plata C, Hebert SC, Gamba G: Characterization of the thiazide-sensitive Na(+)-Cl(-) cotransporter: a new model for ions and diuretics interaction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F161–F169, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zecevic M, Heitzmann D, Camargo SM, Verrey F: SGK1 increases Na,K-ATP cell-surface expression and function in X. laevis oocytes. Pflugers Arch 448: 29–35, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]