Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionary conserved cell process that plays a central role in eukaryotic cell metabolism. Constitutive autophagy allows cells to ensure their energy needs are met during times of starvation, degrade long-lived cellular proteins, and recycle organelles. In addition, autophagy and its machinery can also be utilized to degrade intracellular pathogens, and this function likely represents one of the earliest eukaryotic defense mechanisms against viral pathogens. Within the past decade, it has become clear that autophagy has not only retained its evolutionary ancient ability to degrade intracellular pathogens, but also has co-evolved with the vertebrate immune system to augment and fine tune antiviral immune responses. Herein, we aim to summarize these recent findings as well as to highlight key unanswered questions of the field.

Introduction

The development of compartmentalized structures ubiquitous to eukaryotic cells provided the earliest eukaryotes with numerous evolutionary advantages. However, the development of these organelles presented several novel challenges. Early eukaryotic cells were likely unable to efficiently remove damaged organelles, precisely control organelle number, or utilize their components as an energy source during times of starvation. Autophagy likely represents an evolutionary solution to these challenges, as it enables the recycling of intracellular components via lysosomal degradation. Autophagy is also rapidly induced during starvation conditions and allows cells to survive periods of nutrient deprivation and stress by catabolizing self-components [1]. Moreover, autophagy allows cells to efficiently remove damaged or unneeded intracellular components without relying on cell division or cell death [2]. This ability to maintain long-term cell-autonomous homeostasis [3] likely paved the way for the development of long-lived, terminally differentiated cell types found in metazoans. Indeed, studies with mice with genetic deletion in AuTophaGy (ATG) genes have revealed that long-lived cell types such as neurons [4,5] and cardiomyocytes [6] are incapable of maintaining homeostasis in the absence of autophagy.

It is easy to envision how our early eukaryotic ancestors might have co-opted autophagy to combat another significant challenge – removal of intracellular pathogens [7]. In vertebrates, type I interferons provide a key mechanism of antiviral defense by inducing genes that have direct antiviral activities [8, 9, 10]. Prior to the evolution of the interferon system, however, the eukaryotic host had a limited repertoire of defenses to employ against intracellular pathogens. Autophagy provides eukaryotic cells with a potential means to efficiently remove invading pathogens [11]. Indeed, the autophagy and the ATG proteins have been implicated as playing a key role in the targeting and degradation of numerous bacterial [12, 13], viral [15], and parasitic [14] pathogens. This process, termed xenophagy [16], has been shown to play a critical role in pathogen degradation in multiple model organisms including, C. elegans [17], Drosophila [18], and Mus musculus [16]. Thus, autophagy is an ancient, evolutionary conserved form of defense against intracellular pathogens.

Within the past ten years, several distinct forms of autophagy have been delineated, including macroautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and microautophagy [19]. Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) involves the formation of a double membrane vesicle around intracellular components [20]. The completed vesicle is referred to as an autophagosome, and is subsequently degraded via autophagosome-lysosome fusion. The entire process of autophagosome formation is dependent on the precise coordination of an evolutionary conserved set of Atg genes [20]. However, the molecular mechanism of autophagy is beyond the scope of this review, and has been expertly reviewed elsewhere [21, 22]. Here, we focus on the mechanisms by which autophagy and/or Atg gene products are utilized by the mammalian immune system to coordinate antiviral defense.

Direct role of autophagy in antiviral defense

The first evidence for the role of autophagy in antiviral defense came from Sindbis viral infection. Overexpression of the ATG protein beclin-1 (mammalian orthologue of yeast Atg6) resulted in decreased viral replication and increased survival following intracranial injection of Sindbis virus [23]. Moreover, neuron–specific deletion of the host proteins ATG5 and ATG7 was shown to decrease survival following intracranial injection with Sindbis virus, providing further evidence that autophagy is required in antiviral defense in vivo [24]. Interestingly, viral replication was comparable in the absence of host ATG proteins, but viral proteins were incapable of being cleared in the absence of autophagy. Thus, autophagy, but not necessarily xenophagy of intact virions, is required within neurons to target and remove toxic levels of Sindbis viral proteins.

Further evidence for the role of autophagy in directly controlling viral pathogenesis has come from studies involving members of the herpes family of viruses. Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) encodes a virulence factor, ICP34.5, which inhibits a variety of host antiviral mechanisms. ICP34.5 abrogates protein kinase R (pkr)-dependent translational shutdown [25]. In addition, ICP34.5 blocks autophagy through two distinct pathways; abrogation of PKR-dependent autophagy induction [26]; and through binding and inhibiting beclin-1 [27]. Removal of the beclin-1 binding domain of ICP34.5 resulted in a mutant strain incapable of inhibiting host autophagy initiated by HSV-1 infection. Infection of both fibroblasts and parasympathetic neurons with this HSV-1 mutant resulted in autophagic engulfment of HSV-1 viral particles [28]. Thus, autophagy controls HSV-1 replication at least in part via degradation of HSV-1 virions and / or viral proteins [29].

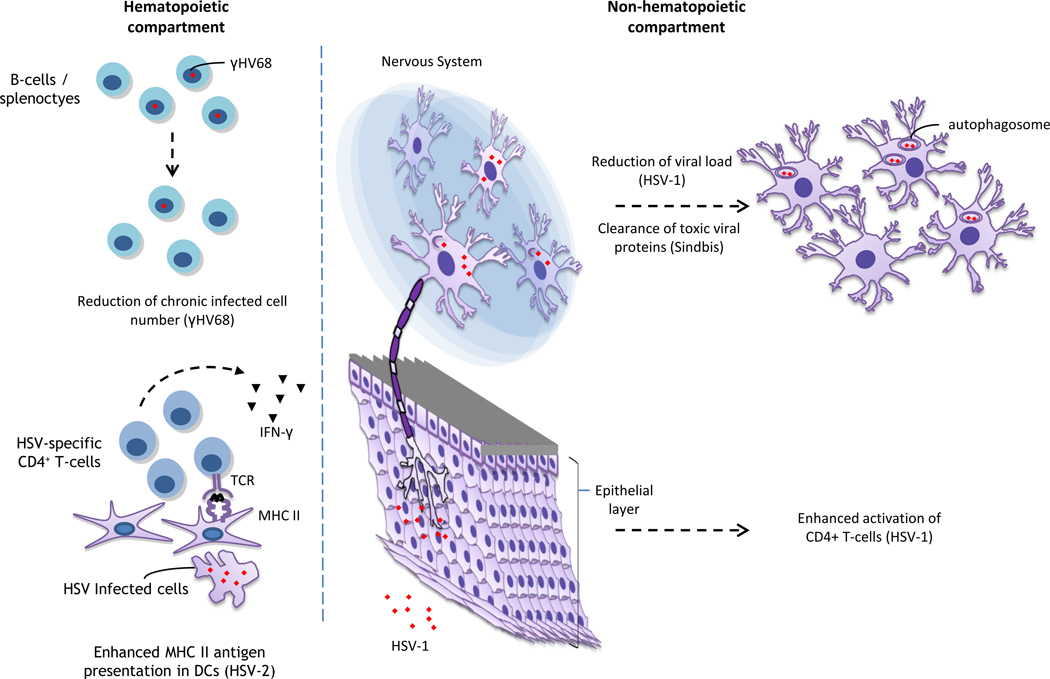

Importantly, autophagy is also critical in anti-HSV-1 defense in vivo (Figure 1) [27]. Intracranial infection with the HSV-1 beclin-1 binding deficient mutant resulted in reduced mortality and decreased HSV-1 replication [27]. The precise mechanism by which autophagy limits HSV-1 replication in these neurons is likely at least partially explained by the aforementioned degradation of HSV-1 viral particles in autophagosomes. Interestingly, no phenotype was observed in in vitro infections of cell lines or primary mouse embyroninc fibroblasts (MEFs) [27, 30]. Future studies are needed to understand the basis for the cell-type specific requirement for autophagy in antiviral defense.

Figure 1. Known roles of the autophagic machinery in vertebrate antiviral defense in vivo.

The autophagy machinery has been shown to impact numerous components of antiviral defense in vivo. γHerpes virus 68 (γHV68) encodes a protein, vbcl2, which inhibits host autophagy. Removal of this domain of vbcl2 results in a mutant virus that has a reduced ability to maintain chronic infection in splenocytes. Autophagy has also been shown to be critical in enhancing presentation of viral antigens in Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. Conditional knockout of ATG5 in DCs result in reduced antigen presentation by DCs, decreased CD4+ T-cell activation, and increased mortality following intravaginal HSV-2 infection. Moreover, removal of the beclin-1 binding domain of the HSV-1 protein ICP34.5 results in increased CD4+ T-cell activation following intraocular HSV-1 infection, presumably by enhancing autophagy-dependent antigen presentation. Autophagy has also been shown to be critical in antiviral defense in neurons. Intracranial infection with the ICP34.5 HSV-1 mutant described above results in increased viral replication and increased mortality. Moreover, genetic deletion of host ATG proteins results in decreased clearance of viral proteins and increased mortality following intracranial infection with Sindbis virus.

Of note, Sindbis virus and HSV-1 are both neurotropic viruses that replicate within neurons. Neurons are widely regarded as an immune privileged cell-type, and limited cytolytic responses are observed against neurons. Intriguingly, autophagy was shown to play a role in limiting VSV replication and decreasing mortality in Drosophila, but not in MEFs in vitro [31]. Drosophila is not a natural host of VSV and is devoid of both an adaptive immune system and type I IFNs [32]. Thus, autophagy may represent an ancient form of antiviral defense that plays a critical role in antiviral defense in systems in which other antiviral mechanisms are absent.

Autophagy as a “fine-tuner” of the antiviral immune response

The autophagy machinery is remarkably conserved from yeast to man. Both autophagy and the vertebrate immune system play essential roles in maintaining cellular and host homeostasis in the face of external perturbations [33]. Such proximal functions imply significant cross-talk between these systems. Indeed, numerous studies in the past decade have revealed that an intimate, reciprocal relationship has evolved between autophagy and the vertebrate immune system [34].

Autophagy plays a critical role in regulating and enhancing multiple aspects of adaptive antiviral immunity, including antigen processing and presentation. Seminal studies by Paludan and colleagues revealed that autophagy plays a critical role in presenting cytosolic viral antigens on MHC II [35]. A plethora of subsequent studies have demonstrated autophagy is critical in mediating presentation of cytosolic viral [36] and host [37] antigens on MHC II, and may also be important in presenting viral antigens on MHC I [38]. Additionally, intraocular infection with an HSV-1 mutant incapable of inhibiting host autophagy resulted in increased CD4+ T-cell activation in vivo and decreased mortality [40], indicating that autophagy within a productively infected cell type is important in activating CD4+ T-cells, presumably via enhanced MHC II antigen presentation.

In addition to the role of autophagy in presentation of cytosolic antigens, a recent in vivo study showed the importance of autophagic machinery in mediating presentation of extracellular antigens by dendritic cells [39]. It is known that extracellular antigens are taken up by phagocytosis and processed in acidic MHC class II compartment (MIIC) for presentation to CD4+ T cells. This study demonstrated that autophagic machinery may play an important role in this process. Thus, Atg proteins are recruited to the phagosomal membrane containing microbial antigens and facilitate fusion with MIIC, there by enhancing processing of antigens for presentation to MHC class II in dendritic cells. The study showed that ATG5 deficient CD11c+ dendritic cells failed to efficiently prime CD4+ T-cells, resulting in increased mortality following intravaginal herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection. DCs that lack Atg5 had an impaired ability to degrade extracellular antigens containing viral PAMPs, leading to reduced levels of MHC II+ peptide complex presented on their cell surface. However, phagosomes containing PAMPs were not surrounded by double membrane structure, and induction of canonical autophagy pathway using rapamycin did not enhance MHC II peptide presentation, indicating that Atg5 facilitates phagosome-to-lysosome fusion by directly recruiting autophagic machinery to the phagosomal membrane.

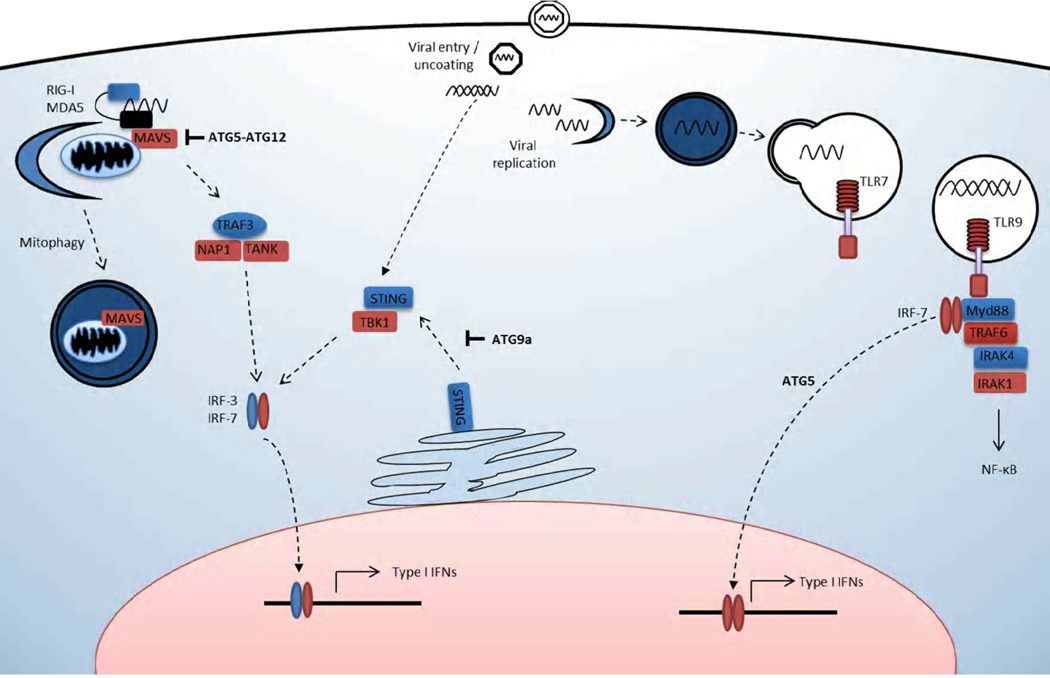

Autophagy and ATG proteins also play a critical role in innate recognition of viruses and the downstream cytokine responses during viral infection (Figure 2). Viruses are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of innate immune system through the detection of viral nucleic acid [41]. Cytosolic nucleic acid is detected by RIG-I like receptors (RLRs), while viral nucleic acid within endosomal compartments is recognized by Toll like receptors (TLRs) [42]. Both detection systems activate IRF3/IRF7 and NF-κB transcription factors, resulting in the production of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines, respectively [41,42]. The relationship between autophagy and innate recognition of viruses was first elucidated in a specialized subset of dendritic cells known as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) [43]. Both pharmacological inhibition and ATG5 genetic deficiency resulted in the absence of recognition of vesicular stromatis virus (VSV) and Sendai virus through TLR-7 [44]. Thus, autophagy is required to facilitate host recognition of viral infection via delivery of viral ligand to the appropriate TLR-containing compartment. In addition, TLR9-dependent production of type I IFN, but not pro-inflammatory cytokines, requires Atg5, indicating that a pathway involving ATG proteins is required for IRF7-dependent signals downstream of TLR9 [43].

Figure 2. Role of autophagy machinery in innate antiviral signaling.

Autophagy and ATG proteins play essential roles in enhancing and precisely regulating antiviral cytokine responses. Autophagy and ATG proteins negatively regulate antiviral cytokine production in non-hematopoietic cells. The ATG5-ATG12 conjugate inhibits production of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines by binding to and inhibiting the Rig I like receptor (RLR) adaptor MAVS. Autophagy also negatively regulates RLR signaling by reducing cellular MAVS and cellular ROS levels by mitophagy. Atg9a negatively regulates the production of antiviral cytokines in response to immunostimulatory DNA by blocking the translocation of STING to TBK1 signaling complexes. In plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), autophagy is required for the delivery of viral PAMP to the TLR-7 signaling compartment. Additionally, ATG5 is required for TLR-9 dependent type I interferon production, but not NF-κB signaling, in pDCs.

In contrast, autophagy has also been shown to attenuate RLR-dependent production of both type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to several viral stimuli in non-hematopoietic cells. The ATG5-ATG12 conjugate binds to MAVS, an adaptor protein downstream of RLR, and abrogates MAVS-dependent type I IFN production independent of canonical autophagy [45]. In addition, in the absence of autophagy, there is an accumulation of both cellular MAVS and damaged mitochondria [46]. This results in elevated levels of both mitochondrial associated reaction oxygen species (ROS) and MAVS, which synergize to amplify RLR signaling. In both studies, ATG5 dependent down-regulation of RLR signaling led to an enhanced VSV replication. Furthermore, it has recently been shown that ATG9a negatively regulates pro-inflammatory cytokine and type I IFN production. ATG9a interacts with STING, a transmembrane protein involved in the immunostimulatory DNA pathway, and prevents translocation to TBK1 signaling complexes [47]. Autophagy can also indirectly regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production, as accumulation of the selective autophagy substrate p62 can oligomerize TRAF6, thus activating downstream NF-κB signaling [48].

Such findings could be extrapolated to argue that the autophagy machinery is ‘pro-viral’, as autophagy-dependent reduction in antiviral cytokines results in increased replication of certain viruses in vitro. However, immune-competent vertebrate hosts are able to sufficiently clear VSV infection [49]. Thus, the additional production of pro-inflammatory cytokines produced in the absence of autophagy is not required in anti-VSV defense. On the contrary, robust cytokine production in the absence of autophagy potentially contributes to a prolonged pro-inflammatory state that is detrimental to the host [50]. In support of this paradigm, several recent studies have demonstrated a link between autophagy deficiency, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and the development of Crohn’s disease. Both humans and mice with a mutation in ATG16L have an increased susceptibility to develop Crohn’s disease [51]. Although multiple defects of the ATG16L mutant host likely contribute to this phenotype, ATG16L deficient cells have increased production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-17 [52, 53]. Recently, Cadwell and colleagues demonstrated that exposure to a specific viral pathogen in ATG16L hypomorphic mice led to increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production and the development of colitis upon physical injury caused by DSS [54]. Thus, in the absence of autophagy, increased cytokine production during viral infection contributes to the development of pathological inflammation.

Viral modulation of host autophagy

The importance of the type I IFN program in antiviral defense is underscored by the observation that numerous viral pathogens have developed countermeasures to antagonize this response [55]. Similarly, it is now clear that many viruses employ strategies to counter and / or subvert host autophagy [56]. These strategies can be broadly classified into three non-mutually exclusive approaches: (1) direct inhibition of host ATG proteins responsible for autophagy induction; (2) downstream interference of autophagy degradation pathway; (3) subverting host autophagy to aid in viral replication.

As discussed above, HSV-1 virulence factor ICP34.5 inhibits autophagy via inhibition of beclin 1 and PKR [27]. Intriguingly, additional members of the herpes family of viruses employ similar strategies to inhibit autophagy. Gamma herpes virus 68 (γHV68) encodes a virulence factor, vbcl2, which inhibits host autophagy via interaction with beclin 1 [57]. Removal of the vbcl2 binding domain results in a significant reduction in the number of chronically γHV68 infected splenocytes in vivo [58]. Further, Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) utilizes vFLIP to interact with ATG3 and inhibit autophagy [59]. Additionally, human cytomegalovirus was recently shown to inhibit autophagy via upstream activation of mTOR signaling [60]. Of note, HSV also encodes a molecule, Us3, which acts as a viral Akt surrogate to activate mTORC1 [61], potentially inhibiting host autophagy upstream of induction as well. Thus, multiple members of the herpesviridae family of viruses employ both evolutionary convergent and divergent strategies to inhibit host autophagy.

In contrast to viruses that have developed mechanisms to inhibit de novo autophagosome formation, influenza and HIV-1 antagonize process downstream of autophagy induction. Although genetic deletion of Atg5 resulted in no significant change in influenza replication in MEFs, influenza-infected WT cells rapidly accumulated autophagosomes [62]. Further analysis revealed that the M2 protein of influenza prevents autophagosome-lysosome fusion. HIV-1 appears to employ an analogous strategy as, HIV-1 nef also blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages [63]. However, the relationship between HIV-1 and autophagy is complex, and seems to be dependent on the infected cell type and viral load [64, 65, 66, 67, 68] (see [67,68] for detailed review). The viral evasion strategy employed by influenza and HIV-1 allows sequestration of virions and viral proteins within autophagosomses. By preventing autophagosome maturation, these viruses circumvent autophagy-dependent degradation and possibly interfere with innate recognition and presentation of viral antigens on MHC molecules. Teleologically, this suggests that a key function of autophagy in antiviral defense against these pathogens is not only viral degradation but also delivering viral components to innate and / or adaptive processing compartments. Indeed, autophagy-dependent presentation of both HIV-1 [69] and influenza [36] antigens have been shown to be key in stimulating virus specific T cells in vitro.

In contrast, several classes of viruses have been reported to require autophagy to achieve maximal viral replication in vitro. Coxsackieviruses (CVB) 3 [70], CVB 4 [71], foot and mouth disease virus [72], and poliovirus [73,74] all induce autophagy upon infection, and siRNA knockdown of host ATG proteins decreases viral yields. Moreover, autophagy is also triggered by ER stress following Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [75]. Pharmacological inhibition or siRNA knockdown of ATG genes results in both decreased translation and replication of HCV RNA [76]. Other studies suggest that the requirement for autophagy in HCV replication may be in part due to negative regulatory role of autophagy on RLR recognition pathway [45, 46], as depletion of Atg expression result in increased antiviral cytokine production after HCV infection [77,78]. Autophagy has also been shown to indirectly aid viral replication in vitro by affecting cell metabolism. siRNA knockdown of Atg genes or pharmacological inhibition of autophagy resulted in decreased Dengue viral replication in vitro [79] and viral RNA may [80] co-localize with autophagic vesicles. Interestingly, siRNA knockdown of Atg genes decreased fatty acid metabolism during Dengue virus infection, and supplementation with fatty acids restored Dengue virus replication to WT levels [81]. These data suggest Dengue virus utilizes autophagy in infected cells to meet the energy needs required for maximal virus replication. Hence, viruses have evolved numerous strategies to subvert the host ATG machinery to directly or indirectly aid multiple aspects of viral replication.

The mechanism(s) by which these viruses subvert the host ATG machinery is an intriguing question that requires further investigation. In several of these host-viral interactions, recent studies have insinuated a sophisticated relationship in which the virus hijacks certain components of the ATG machinery to aid in viral replication, while simultaneously inhibiting functional autophagy. Accordingly, the poliovirus protein 3A inhibits autophagosome movement along the microtubule network [82], potentially antagonizing autophagosome-to-lysosome fusion. CBV 3 has also been shown to functionally block autophagosome maturation [83]. Moreover, autophagy appears to be induced with minimal antiviral effects in certain herpesviridae experimental systems [84,85]. Thus, the current distinction between viruses that inhibit autophagy and those that require the autophagy machinery for maximal viral replication might yet prove to be not so black and white.

Importantly, several studies have shown that genetic deletion of host ATG proteins results in both increased morbidity and mortality following viral infection in vivo (Figure 1). Interestingly, no current studies have demonstrated the converse - the absence of autophagy results in reduced viral replication, morbidity, or mortality in vivo. This may simply be due to the model systems employed by investigators, and future studies might yet reveal in vivo models (e.g. HCV) in which the absence of autophagy is beneficial to the mammalian host during virus infection. However, we suspect that this scenario is unlikely. Although autophagy inhibition in vivo may reduce local replication of certain viruses, such a reduction comes at a high cost – failure to robustly activate and precisely regulate innate and adaptive immunity.

Conclusion

Autophagy has not only retained an evolutionary ancient ability to eliminate intracellular pathogens but also has co-evolved with the immune system to fine-tune, enhance, and regulate numerous antiviral immunological responses. Although our understanding of autophagy in antiviral immunity has increased exponentially within the past decade, many ambiguities remain. Foremost of these is understanding the complex relationship that exists between the numerous immunological processes autophagy has been implicated in and the various components of the ATG machinery. In many of the previously discussed studies, it is unclear whether or not autophagy, or distinct components / proteins of the autophagic machinery, are the key mediators of the observed phenotype [86]. This ambiguity is not trivial, as development of successful autophagy antiviral therapeutics requires understanding of the appropriate molecular pathways to target. Along these lines, the development of pharmacological agents that specifically induce autophagy is a key future goal [87]. Although numerous autophagy-inducing pharmacological agents are widely employed, the vast majority of these induce autophagy through modulation of upstream signaling nodes, all of which have pleiotropic effects in vitro and in vivo [87, 88]. The development of specific inducers of autophagy will not only serve as a powerful tool for investigators to dissect the roles of the autophagy versus the Atg proteins but also offer promise as a novel class of antiviral therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AI054359, AI062428, AI064705 and AI083242 to A.I.). A.I. holds an Investigators in Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. B.Y. was supported by the Interdisciplinary Immunology Training Program grant T 32 AI 07019, 33. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, Mizushima N. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata J-, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 2007;13:619–624. doi: 10.1038/nm1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuel CE. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen GC. Viruses and interferons. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Type I Interferons in Host Defense. Immunity. 2006;25:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deretic V, Levine B. Autophagy, Immunity, and Microbial Adaptations. Cell Host and Microbe. 2009;5:527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh SB, Davis AS, Taylor GA, Deretic V. Human IRGM induces autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria. Science. 2006;313:1438–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, Miller BC, Cadwell K, Delgado MA, Ponpuak M, Green KG, et al. Autophagosome-Independent Essential Function for the Autophagy Protein Atg5 in Cellular Immunity to Intracellular Pathogens. Cell Host and Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumpter R, Levine B. Autophagy and innate immunity: Triggering, targeting and tuning. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2010;21:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: Autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell. 2005;120:159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia K, Thomas C, Akbar M, Sun Q, Adams-Huet B, Gilpin C, Levine B. Autophagy genes protect against Salmonella typhimurium infection and mediate insulin signaling-regulated pathogen resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14564–14569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813319106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano T, Mita S, Ohmori H, Oshima Y, Fujimoto Y, Ueda R, Takada H, Goldman WE, Fukase K, Silverman N, et al. Autophagic control of listeria through intracellular innate immune recognition in drosophila. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:908–916. doi: 10.1038/ni.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majeski AE, Fred Dice J. Mechanisms of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2435–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:421–429. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: Lessons from yeast. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10:458–467. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang XH, Kleeman LK, Jiang HH, Gordon G, Goldman JE, Berry G, Herman B, Levine B. Protection against fatal sindbis virus encephalitis by Beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J Virol. 1998;72:8586–8596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8586-8596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orvedahl A, MacPherson S, Sumpter R, Jr, Tallόczy Z, Zou Z, Levine B. Autophagy Protects against Sindbis Virus Infection of the Central Nervous System. Cell Host and Microbe. 2010;7:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.007.. This paper defined the mechanism by which autophagy is important in Sindbis antiviral defense in vivo, as well as provided the first evidence that viral proteins are specifically targeted to autophagosomes.

- 25.He B, Gross M, Roizman B. The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1α to dephosphorylate the α subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:843–848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tallόczy Z, Jiang W, Virgin HW, IV, Leib DA, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Eskelinen E-, Levine B. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the elF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:190–195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012485299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Orvedahl A, Alexander D, Tallόczy Z, Sun Q, Wei Y, Zhang W, Burns D, Leib DA, Levine B. HSV-1 ICP34.5 Confers Neurovirulence by Targeting the Beclin 1 Autophagy Protein. Cell Host and Microbe. 2007;1:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001.. This study provided the first evidence that viral pathogens encode virulence factors that inhibit autophagy and that this inhibition antagonizes host antiviral defense in vivo.

- 28.Tallόczy Z, Virgin HW, IV, Levine B. PKR-dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy. 2006;2:24–29. doi: 10.4161/auto.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander DE, Leib DA. Xenophagy in herpes simplex virus replication and pathogenesis. Autophagy. 2008;4:101–103. doi: 10.4161/auto.5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander DE, Ward SL, Mizushima N, Levine B, Leib DA. Analysis of the role of autophagy in replication of herpes simplex virus in cell culture. J Virol. 2007;81:12128–12134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01356-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shelly S, Lukinova N, Bambina S, Berman A, Cherry S. Autophagy Is an Essential Component of Drosophila Immunity against Vesicular Stomatitis Virus. Immunity. 2009;30:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leclerc V, Reichhart J- The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelekar A. Autophagy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1066:259–271. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paludan C, Schmid D, Landthaler M, Vockerodt M, Kube D, Tuschl T, Münz C. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science. 2005;307:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1104904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmid D, Pypaert M, Münz C. Antigen-Loading Compartments for Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Molecules Continuously Receive Input from Autophagosomes. Immunity. 2007;26:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nedjic J, Aichinger M, Emmerich J, Mizushima N, Klein L. Autophagy in thymic epithelium shapes the T-cell repertoire and is essential for tolerance. Nature. 2008;455:396–400. doi: 10.1038/nature07208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.English L, Chemali M, Duron J, Rondeau C, Laplante A, Gingras D, Alexander D, Leib D, Norbury C, Lippé R, Desjardins M. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:480–487. doi: 10.1038/ni.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee HK, Mattei LM, Steinberg BE, Alberts P, Lee YH, Chervonsky A, Mizushima N, Grinstein S, Iwasaki A. In Vivo Requirement for Atg5 in Antigen Presentation by Dendritic Cells. Immunity. 2010;32:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.006.. This study that demonstrated that host ATG machinery is critical in antigen presentation of viral pathogens in vivo.

- 40.Leib DA, Alexander DE, Cox D, Yin J, Ferguson TA. Interaction of ICP34.5 with beclin 1 modulates herpes simplex virus type 1 pathogenesis through control of CD4+ T-cell responses. J Virol. 2009;83:12164–12171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01676-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee HK, Lund JM, Ramanathan B, Mizushima N, Iwasaki A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science. 2007;315:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1136880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manuse MJ, Briggs CM, Parks GD. Replication-independent activation of human plasmacytoid dendritic cells by the paramyxovirus SV5 Requires TLR7 and autophagy pathways. Virology. 2010;405:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jounai N, Takeshita F, Kobiyama K, Sawano A, Miyawaki A, Xin K-, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, Akira S, Suzuki K, Okuda K. The Atg5–Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14050–14055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tal MC. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen speciesdependent amplification of RLR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2770–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807694106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saitoh T, Fujita N, Hayashi T, Takahara K, Satoh T, Lee H, Matsunaga K, Kageyama S, Omori H, Noda T, et al. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20842–20846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911267106.. This report demonstrates the ATG machinery negatively regulates innate antiviral signaling by regulating the localization of innate signaling components.

- 48.Sanz L, Diaz-Meco MT, Nakano H, Moscat J. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-κB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J. 2000;19:1576–1586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iannacone M, Moseman EA, Tonti E, Bosurgi L, Junt T, Henrickson SE, Whelan SP, Guidotti LG, Von Andrian UH. Subcapsular sinus macrophages prevent CNS invasion on peripheral infection with a neurotropic virus. Nature. 2010;465:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature09118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saitoh T, Akira S. Regulation of innate immune responses by autophagy-related proteins. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:925–935. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Brant SR, Silverberg MS, Taylor KD, Barmada MM, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:955–962. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, Kishi C, Kc W, Carrero JA, Hunt S, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, Uematsu S, Yang B-, Satoh T, Omori H, Noda T, Yamamoto N, Komatsu M, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1β production. Nature. 2008;456:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature07383.. This study (along with [52]) provided the first evidence that genetic deficiency of Atg16L can lead to increased cytokine production in vitro and contribute to pathological inflammation in vivo.

- 54. Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, Liu T-, Ng ACY, Storer CE, Head RD, Xavier R, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW. Virus-Plus-Susceptibility Gene Interaction Determines Crohn's Disease Gene Atg16L1 Phenotypes in Intestine. Cell. 2010;141:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009.. This study revealed that an interaction between a specific virus infection and a mutation in the host gene Atg16L1 induces intestinal pathology in vivo.

- 55.García-Sastre A, Biron CA. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: A lesson in détente. Science. 2006;312:879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1125676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orvedahl A, Levine B. Autophagy in mammalian antiviral immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:267–285. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ku B, Woo J-, Liang C, Lee K-, Hong H-, E X, Kim K-, Jung JU, Oh B- Structural and biochemical bases for the inhibition of autophagy and apoptosis by viral BCL-2 of murine γ-herpesvirus 68. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.E X, Hwang S, Oh S, Lee J-, Jeong JH, Gwack Y, Kowalik TF, Sun R, Jung JU, Liang C. Viral Bcl-2-mediated evasion of autophagy aids chronic infection of γherpesvirus 68. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J-, Li Q, Lee J-, Lee S-, Jeong JH, Lee H-, Chang H, Zhou F-, Gao S-, Liang C, Jung JU. FLIP-mediated autophagy regulation in cell death control. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1355–1362. doi: 10.1038/ncb1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaumorcel M, Souquère S, Pierron G, Codogno P, Esclatine A. Human cytomegalovirus controls a new autophagy-dependent cellular antiviral defense mechanism. Autophagy. 2008;4:46–53. doi: 10.4161/auto.5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chuluunbaatar U, Roller R, Feldman ME, Brown S, Shokat KM, Mohr I. Constitutive mTORC1 activation by a herpesvirus Akt surrogate stimulates mRNA translation and viral replication. Genes and Development. 2010;24:2627–2639. doi: 10.1101/gad.1978310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gannagé M, Dormann D, Albrecht R, Dengjel J, Torossi T, Rämer PC, Lee M, Strowig T, Arrey F, Conenello G, et al. Matrix Protein 2 of Influenza A Virus Blocks Autophagosome Fusion with Lysosomes. Cell Host and Microbe. 2009;6:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.005.. This paper demonstrated influenza M2 protein inhibits autophagosome maturation by preventing lysosome fusion.

- 63.Kyei GB, Dinkins C, Davis AS, Roberts E, Singh SB, Dong C, Wu L, Kominami E, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, et al. Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:255–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Denizot M, Varbanov M, Espert L, Robert-Hebmann V, Sagnier S, Garcia E, Curriu M, Mamoun R, Blanco J, Biard-Piechaczyk M. HIV-1 gp41 fusogenic function triggers autophagy in uninfected cells. Autophagy. 2008;4:998–1008. doi: 10.4161/auto.6880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Espert L, Denizot M, Grimaldi M, Robert-Hebmann V, Gay B, Varbanov M, Codogno P, Biard-Piechaczyk M. Autophagy is involved in T cell death after binding of HIV-1 envelope proteins to CXCR4. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2161–2172. doi: 10.1172/JCI26185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou D, Spector SA. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection inhibits autophagy. AIDS. 2008;22:695–699. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4a836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dinkins C, Arko-Mensah J, Deretic V. Autophagy and HIV. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Espert L, Biard-Piechaczyk M. Autophagy in HIV-induced T cell death. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:307–321. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blanchet FP, Moris A, Nikolic DS, Lehmann M, Cardinaud S, Stalder R, Garcia E, Dinkins C, Leuba F, Wu L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 inhibition of immunoamphisomes in dendritic cells impairs early innate and adaptive immune responses. Immunity. 2010;32:654–669. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wong J, Zhang J, Si X, Gao G, Mao I, McManus BM, Luo H. Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J Virol. 2008;82:9143–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seung YY, Young EH, Jung EC, Ahn J, Lee H, Kweon H-, Lee J-, Dong HK. Coxsackievirus B4 uses autophagy for replication after calpain activation in rat primary neurons. J Virol. 2008;82:11976–11978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01028-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O'Donnell V, Pacheco JM, LaRocco M, Burrage T, Jackson W, Rodriguez LL, Borca MV, Baxt B. Foot-and-mouth disease virus utilizes an autophagic pathway during viral replication. Virology. 2011;410:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taylor MP, Kirkegaard K. Modification of cellular autophagy protein LC3 by poliovirus. J Virol. 2007;81:12543–12553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00755-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suhy DA, Giddings THJ, Kirkegaard K. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: An autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J Virol. 2000;74:8953–8965. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8953-8965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sir D, Chen W-, Choi J, Wakita T, Yen TSB, Ou J-J. Induction of incomplete autophagic response by hepatitis C virus via the unfolded protein response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1054–1061. doi: 10.1002/hep.22464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dreux M, Gastaminza P, Wieland SF, Chisari FV. The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Aug 18;106:14046–14051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907344106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ke P-, Chen SS- Activation of the unfolded protein response and autophagy after hepatitis C virus infection suppresses innate antiviral immunity in vitro. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:37–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI41474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shrivastava S, Raychoudhuri A, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Knockdown of autophagy enhances the innate immune response in hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2011;53:406–414. doi: 10.1002/hep.24073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee Y-, Lei H-, Liu M-, Wang J-, Chen S-, Jiang-Shieh Y-, Lin Y-, Yeh T-, Liu C-, Liu H- Autophagic machinery activated by dengue virus enhances virus replication. Virology. 2008;374:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khakpoor A, Panyasrivanit M, Wikan N, Smith DR. A role for autophagolysosomes in dengue virus 3 production in HepG2 cells. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:1093–1103. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.007914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heaton NS, Randall G. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host and Microbe. 2010;8:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taylor MP, Burgon TB, Kirkegaard K, Jackson WT. Role of microtubules in extracellular release of poliovirus. J Virol. 2009;83:6599–6609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01819-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kemball CC, Alirezaei M, Flynn CT, Wood MR, Harkins S, Kiosses WB, Whitton JL. Coxsackievirus infection induces autophagy-like vesicles and megaphagosomes in pancreatic acinar cells in vivo. J Virol. 2010;84:12110–12124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01417-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee DY, Sugden B. The latent membrane protein 1 oncogene modifies B-cell physiology by regulating autophagy. Oncogene. 2008;27:2833–2842. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taylor GS, Mautner J, Munz C. Autophagy in herpesvirus immune control and immune escape. Herpesviridae. 2011;2:2. doi: 10.1186/2042-4280-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Virgin HW, Levine B. Autophagy genes in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:461–470. doi: 10.1038/ni.1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nature Chemical Biology. 2011;7:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Easton JB, Houghton PJ. Therapeutic potential of target of rapamycin inhibitors. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2004;8:551–564. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]