Abstract

Dystonia is a motor sign characterized by involuntary muscle contractions which produce abnormal postures. Genetic factors contribute significantly to primary dystonia. In comparison, secondary dystonia can be caused by a wide variety of metabolic, structural, infectious, toxic and inflammatory insults to the nervous system. Although classically ascribed to dysfunction of the basal ganglia, studies of diverse animal models have pointed out that dystonia is a network disorder with important contributions from abnormal olivocerebellar signaling. In particular, work with the dystonic (dt) rat has engendered dramatic paradigm shifts in dystonia research. The dt rat manifests generalized dystonia caused by deficiency of the neuronally-restricted protein caytaxin. Electrophysiological and biochemical studies have shown that defects at the climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapse in the dt rat lead to abnormal bursting firing patterns in the cerebellar nuclei, which increases linearly with postnatal age. In a general sense, the dt rat has shown the scientific and clinical communities that dystonia can arise from dysfunctional cerebellar cortex. Furthermore, work with the dt rat has provided evidence that dystonia (1) is a neurodevelopmental network disorder and (2) can be driven by abnormal cerebellar output. In large part, work with other animal models has expanded upon studies in the dt rat and shown that primary dystonia is a multi-nodal network disorder associated with defective sensorimotor integration. In addition, experiments in genetically-engineered models have been used to examine the underlying cellular pathologies that drive primary dystonia.

Keywords: Dystonia, Inferior olive, Purkinje cell, Caytaxin, TorsinA, Basal ganglia

Introduction

It is not possible to envision the field of movement disorders research without animal models. Normal and pathological motor behavior is the final produce of massive neural computations performed by tissues with precise but plastic three-dimensional structures with exacting connectivity patterns. Mammalian models are often essential for evaluating the efficacy of candidate drugs and devices that target specific receptors and/or structures in the brain. Accordingly, in vitro studies are often limited to biochemical and cell biology questions.

The choice of model system (e.g., patients, rodents, primates, in silico, test tube, or cultured neurons) is largely dictated by the particular hypothesis and overall experimental goals. The decision to utilize an animal model should be intimately incorporated with choice of species. Common invertebrate models include the roundworm (Caenorhabditis elegans) and fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). C. elegans only requires 3 days to develop to maturity, is translucent and very inexpensive, and can be frozen for long-term storage. Drosophila is highly amenable to sophisticated genetic manipulation with powerful tools such as the GAL4-UAS system. The mouse (Mus musculus) is the standard choice of mammalian species in most laboratories, particularly when genetic manipulations of the genome are planned. However, in recent years, transgenic techniques have also been applied to rats, ungulates and non-human primates. Primates are typically employed for pre-clinical testing of neuromodulatory devices.

Genetically dystonic rat

The genetically dystonic rat (SD-dt:JFL) is an autosomal recessive animal model of primary generalized dystonia. The dt rat is a spontaneous mutant discovered in the Sprague-Dawley (SD) strain. The dt rat develops a dystonic motor syndrome by Postnatal Day 12 (P12, Lorden et al. 1984). The mutation is fully penetrant and there is negligible variability to its expressivity. Mutations in the coding region of the gene (TOR1A) associated with DYT1 dystonia have been excluded in the dt rat (Ziefer et al. 2002). Dystonic rats exhibit both axial and appendicular dystonia that progresses in severity with increasing postnatal age. Neonatal dt rats can be reliably differentiated from normal littermates by P12. Prior to P10, normal and dt rats have an identical motor phenotype and display qualitatively similar motor activities in the open field (e.g., head elevation, grooming, crawling, and quadruped stability). Dystonia is reduced when the animals are at rest and disappears during sleep. Without surgical intervention, dt rats develop a progressive, severe, generalized dystonia that involves both the limbs and truncal musculature, and, invariably, leads to death prior to P40 despite gavage feedings and other supportive measures.

There are no gross differences between normal and dt rats in terms of brain morphology. Microscopic analysis of cresyl violet, hematoxylin and eosin, Luxol fast blue, periodic acid-Schiff and silver-stained central and peripheral nervous tissues from dt rats has shown no differences from normals (Lorden et al. 1984, LeDoux et al. 1995). Because they are a central component of the basal ganglia, the morphology of striatal neurons was examined with Golgi impregnation in both dt and normal rats; no abnormalities were detected in the mutants (McKeon et al. 1984).

Anatomical studies in the dt rat have focused on olivocerebellar pathways. Dystonic rats and normal littermates do not exhibit differences in Purkinje cell number, volume of the cerebellar nuclei, soma size of cerebellar nuclear neurons, molecular layer thickness, or granular cell layer thickness, although, in vermian and paravermian tissues at P20, Purkinje cells are 5–11% smaller in dt rats than in normal littermates (Lorden et al. 1985, 1992). This effect is not generalized since there are no differences in the size of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus. Furthermore, Purkinje cell dendritic arborizations are qualitatively similar between normal and dt rats. The inferior olivary projection to cerebellar cortex was studied with both anterogradely and retrogradely transported horseradish peroxidase. The connectivity pattern was consistent with studies in normal rats, and cerebellar cortical terminations were normal at the level of light microscopy (Stratton 1991).

The second messenger, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), together with cGMP-dependent protein kinases types I and II are expressed at high levels in cerebellar Purkinje cells (de Vente et al. 2001). Basal levels of cGMP are decreased in dt rat cerebellar cortex (Lorden et al. 1985). In addition, the increase in cerebellar cGMP seen in normal rats after the systemic administration of harmaline is much smaller in dt rats. These findings suggest that a defect in neurotransmission, probably postsynaptic, is present in dt rat cerebellar cortex.

Profound changes in GABAergic markers were then isolated to the cerebellar nuclei and Purkinje cells in the dt rat. In the dt rat cerebellar nuclei, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) activity was found to increase with increasing postnatal age (Oltmans et al. 1986, Beales et al. 1990). Opposite changes were noted in cerebellar nuclear GABAA receptors. In contrast, there were no changes in GABA levels or binding of the benzodiazepine ligand, muscimol (Beales et al. 1990, Lutes et al. 1992). The distribution, size and density of GAD-immunoreactive puncta in the cerebellar nuclei was examined in normal and dt rats; the only abnormality noted was a relative decrease in puncta density at P25 in dt rats (Lutes et al. 1992). With quantitative in situ hybridization, GAD67 mRNA was increased in Purkinje cells and decreased in the cerebellar nuclei of dt rats (Naudon et al. 1998). In aggregate, these findings are most compatible with increased activity of Purkinje cell GABAergic synapses within the dt rat cerebellar nuclei. The changes in cerebellar nuclear GABAA receptors and GAD67 transcript are probably compensatory responses.

To test the hypothesis that cerebellar dysfunction is critical to the expression of the dt rat motor phenotype, groups of dt rats and normal littermates underwent cerebellectomy (CBX) at P15 (LeDoux et al. 1993). The entopeduncular nuclei were lesioned with kainic acid in a separate group of dt rats. Age-matched unoperated dt rats served as controls. CBX included the dorsal portion of the lateral vestibular nucleus, a structure that receives direct projections from cerebellar Purkinje cells. After CBX, normal and dt rats could not be differentiated by behavioral observation or simple tests of motor function. Although non-operated rats performed better than CBX rats on tests of righting and tended to perform better on a climbing task, the differences were not striking. This is due, in part, to the milder effects of CBX on both young animals and rodents when compared to adults and higher species, respectively. CBX rats were, however, unable to perform more complex motor tasks such as narrow beam walking that are not difficult for non-operated rats. The group of dt rats with bilateral lesions of the entopeduncular nucleus showed no significant improvement in motor function. After CBX, dt rats survive into adulthood without additional treatment. The lifespan of post-CBX dt rats is equivalent to that of normal littermates. Furthermore, post-CBX dt rats are able to mate and rear their offspring.

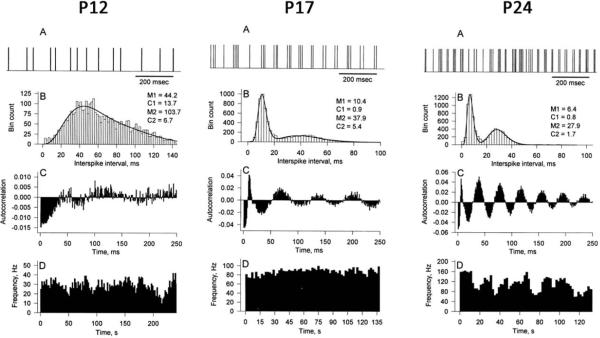

Electrophysiological studies in awake dt rats have been essential for the rational explanation of olivocerebellar network abnormalities in the mutants. In comparison with normal rats, cerebellar nuclear cells from awake dt rats as young as P12 show bursting firing patterns (Fig. 1). Bursting activity increases with increasing postnatal age in dt rats (LeDoux et al. 1998). Many cerebellar nuclear cells from older dt rats exhibit rhythmic bursting activity that shows little modification in response to either sensory stimuli or motor activity. The bursting firing patterns displayed by cerebellar nuclear neurons from dt rats can be attributed to a low-threshold inactivating calcium-dependent conductance that generates rebound excitation following transient membrane hyperpolarization (Llinás and Mühlethaler 1988).

Fig. 1.

Single-unit extracellular recordings from cerebellar nuclei in dt rats at P12, P17, and P24. (A) Representative portion of the spike trains. (B) Interspike interval histograms with parameters from a double-gamma distribution. (C) Autocorrelations. (D) Ratemeter histograms.

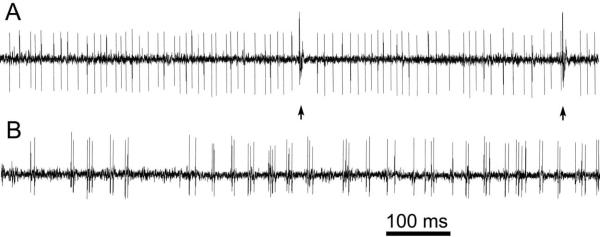

With single-unit awake recordings from cerebellar cortex, there was a trend for Purkinje cell simple-spike frequency to be higher in dt than in age-matched normal rats. In distinction, Purkinje cell complex-spike frequency was markedly lower in normal than in dt rats (Fig. 2). As demonstrated in Fig. 2, Purkinje cells from dt rats, particularly cells from the vermis or older animals, exhibited rhythmic bursting simple-spike firing patterns.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous Purkinje cell spike trains from normal (A) and dt (B) rats. Complex spikes are marked with arrows.

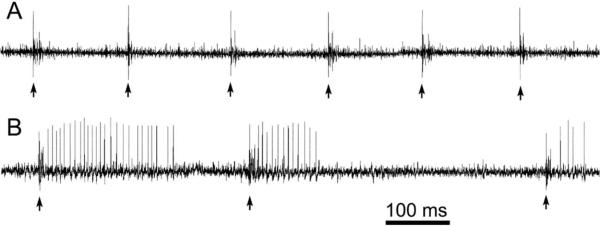

Inferior olivary firing rates were lower in dt rats than in normal littermates (Stratton and Lorden 1991). In contrast, there were no significant differences in inferior olivary post-harmaline firing rates between normal and dt rats (Stratton and Lorden 1991). After the systemic administration of harmaline, complex-spike frequency increased in both normal and dt rats although it remained lower in the mutants. As seen in Fig. 3, harmaline-stimulated complex spike activity was also more rhythmic and produced greater suppression of simple spikes in normal than in dt rats (LeDoux and Lorden 2002). These electrophysiological findings along with earlier biochemical data indicate that dt rats harbor a defect in their climbing fiber input to Purkinje cells.

Fig. 3.

Harmaline-stimulated Purkinje cell spike trains from normal (A) and dt (B) rats. Complex spikes are marked with arrows.

In order to identify the mutant gene responsible for the dt rat motor syndrome, a female spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) was bred with a post-CBX male dt rat. Microsatellite markers were spaced approximately 5 cM apart along the 20 rat autosomes. The SHR dam and post-CBX male dt rat (F0 generation) were bred twice to yield a total of 23 phenotypically-normal heterozygotic F1 rats. Heterozygote F1 rats (SD-dt/SHR) were crossbred to produce 875 F2 offspring. The genotypes of phenotypically normal F2 rats (heterozygote versus homozygote) were determined by breeding with post-CBX dt rats. After the first round of genotyping 69 F2 rats, three markers (D7Rat36, D7Rat35 and D7Rat32) showed strong linkage disequilibrium with the dystonic phenotype. More refined mapping was performed with additional microsatellite markers in 875 F2 rats.

In brief, haplotype analyses, recombination rates, and, in part, the SHRSP × BN genetic map were used to order the microsatellite markers and determine that the mutant gene was likely located between D7Rat188 and D7Rat113 (6.795–10.973Mb) within Contig NW_047773. Syntenic relationships among rat, human and mouse genomes were then rigorously examined in silico. We established that chromosomal loci syntenic with the “dt” locus (Chr 7q11) were Chr 12q13.13/ 19p13.3 and Chr 10D3/10C1 in human and mouse, respectively. Candidate genes within the dt locus were screened for mutations using semi-quantitative reverse transciptase (RT)-PCR. Primers were designed to amplify the entire coding regions of genes within the dt locus. Forty of the 105 genes within the “dt” locus were screened prior to detecting low expression levels of Atcay in dt rats.

Atcay cDNA, 5'-UTR, exon, and splice site sequences showed no differences between dt rats and normal littermates. Since Atcay coding sequences were normal, Southern blotting with a 5'-UTR cRNA probe was performed in search of an insertional mutation within 5'-Atcay. Restriction enzymes PvuII and MspI produced normal sized restriction fragments. In contrast, TaqI and PstI generated larger fragments with dt rat genomic DNA. Restriction site mapping identified an insertion in Intron 1.

PCR primers were designed to broadly flank the putative insertion site in Intron 1 of dt rat Atcay (Atcaydt). The 429-bp insertion was identified as the 3′-long terminal repeat (3′-LTR) of rat intracisternal A-particle (IAP) elements. The 3′-LTR insertion target site in the dt rat contains a 6-bp duplication (AACATA) such that a total of 435 bp are added to Atcay Intron 1 in dt rats (Atcaydt). The transcriptional orientations of Atcay and the 3′-LTR insertion are in the same direction. The 3′-LTR insertion contains transcriptional elements (Sp1, CAAT box, and TATA box), a 15-bp triplet repeat, and a polyadenylation signal (AGTAAA).

The 3′-LTR insertion in Intron 1 dramatically reduces the production of Atcay transcript. With Northern blots, three Atcay transcripts (1.8, 2.5 and 4.2 kb) were present in both cerebellar and cerebral cortical tissues from normal rats. In contrast, these bands were not clearly detectable in dt rats. As determined with relative quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR), mean cerebellar and cerebral cortical Atcay transcript levels in P15 dt rats were only 4.1% and 1.2% of normal, respectively. In comparison, mean cerebellar and cerebral cortical Atcay transcript levels in P15 heterozygotes were 53.1% and 60.0% of normal, respectively. Western blotting with polyclonal antibodies generated in mouse and rabbit were used to examine the consequences of the insertional mutation on translation of caytaxin. Marked reductions in cerebellar caytaxin levels were seen with both antibodies. In harmony with the results of QRT-PCR, an intermediate reduction of cerebellar caytaxin levels was seen in heterozygote littermates. The SD rat Atcay gene (AY611623) contains 13 exons with an open reading frame of 1116 bp that encodes a 372-amino acid protein with 97% and 91% identity to mouse and human caytaxin amino acid-sequences, respectively.

Three Atcay transcripts were identified in brain but none were present in heart, spleen, lung, liver, muscle, kidney or testis. QRT-PCR was performed with RNA extracted from cerebral cortex, striatum, thalamus, hippocampus and cerebellum. Atcay transcript levels peaked at P7 in hippocampus, increased linearly from P1 to P36 in cerebellum, and showed minimal developmental regulation in cerebral cortex. With in situ hybridization, Atcay transcript was localized to dorsal root ganglia, peripheral ganglia, and seemingly all neuronal populations in brain. In cerebellum, Atcay transcript was present in the molecular, Purkinje and granular layers; transcript density in the molecular layer peaked at P14.

A listing of caytaxin model systems is provided in Table 1. Cayman ataxia is limited to inhabitants of Grand Cayman Island (Bomar et al. 2003). To date, ATCAY mutations have not been identified in other populations with ataxia or dystonia. Unfortunately, detailed descriptions of the “Cayman ataxia” phenotype have not been published in refereed journals, and, as such, the presence of dystonia cannot be excluded. Clinical manifestations of “Cayman ataxia” may include psychomotor retardation, ataxic gait, “scoliosis,” nystagmus. Cerebellar atrophy was detected on computed tomography imaging. Cayman ataxia is autosomal recessive and apparently non-progressive.

Table 1.

Caytaxin model systems

| Model | Mutation Location | Type of Mutation | Transcripts | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cayman ataxia (human) | Exon9/lntron 9 | C→G missense G→T splice site |

Unknown | gait ataxia, hypotonia, mental retardation, nystagmus, intention tremor, dysarthria |

| Dystonic rat | Intron 1 | IAP element insertion | all markedly reduced | severe generalized dystonia, die by 4–5 weeks |

| Jittery mouse | Exon 4 | B1 element insertion, Alu-related mutagenesis | aberrant largest transcript, smaller transcript markedly reduced | severe truncal and limb ataxia, dystonic forelimb spasms, die by 3–4 weeks |

| Hesitant mouse | Intron 1 | IAP element insertion | aberrant larger transcripts with small amounts of normal transcript | mild ataxia, dystonia |

| Sidewinder mouse | Exon 5 | 2-bp deletion | all markedly reduced | severe truncal and limb ataxia, dystonic forelimb spasms, die by 3–4 weeks |

Although not well studied, murine models of caytaxin deficiency show evidence of dystonia in addition to ataxia. Jittery homozygotes exhibit a zigzag gait when attempting to run and have great difficulty righting after placement on their backs (Kapfhamer et al. 1996). By P14, jittery homozygotes crouch on their heels in a squatting position and cannot run without falling. Forelimb dystonic spasms occur by P16. The jittery allele of Atcay has a B1 element inserted into exon 4, which, if transcribed and translated, would produce a truncated protein of only 62 amino acids (Gilbert et al. 2004). Hesitant homozygotes can be discerned at P14 by an unusual hesitant walking motion. After the third postnatal week, the hindlimbs of hesitant homozygotes are maintained in a stiff extended position causing the posterior trunk to rise abnormally during ambulation. The posturing of hesitant mice is consistent with dystonia and similar to waddles mice (Jiao et al. 2005, Jinnah et al. 2005). Homozygote sidewinder mice are phenotypically similar to jittery mice (Bomar et al. 2003).

Caytaxin contains a hydrophobic binding pocket within a CRAL-TRIO domain, a motif common to certain proteins that bind lipophilic molecules like α-tocopherol, retinal, phosphatidylcholine, and the phosphatidylinositols (Bomar et al. 2003). Although caytaxin is highly conserved among mammals, the entirety of its sequence shows weaker homology with invertebrate proteins. The CRAL-TRIO domain can also be found in plants and fungi. A CRAL-TRIO domain is the major component of the well-characterized SEC14 protein found in yeast. Some patients with mutations in the gene that encodes α-tocopherol transfer protein, another protein containing a CRAL-TRIO domain, exhibit dystonia as a major component of their phenotype. Structural analysis suggests that the ligand-binding pocket of caytaxin is more polar than that of α-tocopherol transfer protein. By extrapolation, it is plausible that caytaxin binds a lipophilic ligand essential to calcium signaling in cerebellar Purkinje cells.

The binding cavity of caytaxin is suited for an amphipathic ligand like a phosphatidylinositol (Bomar et al. 2003, Panagabko et al. 2003, Xiao and LeDoux 2005). Compatible with this hypothesis, genes encoding the phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate adaptor protein 1, phospholipid scramblase 3, and inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 were upregulated in dt rat cerebellar cortex (Xiao et al. 2007). Conversely, genes encoding inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase (INPP1), inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphastase A and frequenin were downregulated in the dt rat. INPP1 removes the 1 position phosphate from inositol 1,3,4-triphosphate and inositol 1,4-diphosphate, thereby producing inositol 3,4-diphosphate and inositol 4-phosphate, respectively (Inhorn and Majerus 1988).

In addition to phosphatidylinositol signaling pathways, data derived from oligonucleotide microarrays and QRT-PCR identified calcium homeostasis and extracellular matrix interactions as domains of cellular dysfunction in dt rats (Xiao et al. 2007). In dt rats, genes encoding the corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRH-R1, Crhr1) and calcium-transporting plasma membrane ATPase 4 (PMCA4, Atp2b4) showed the greatest up-regulation with QRT-PCR. Immunocytochemical experiments demonstrated that CRH-R1 and PMCA4 were upregulated in cerebellar cortex of mutant rats. CRH-R1 and PMCA4 were upregulated in distinct cellular compartments within the molecular layer of cerebellar cortex. CRH-R1 was upregulated in Purkinje cells whereas PMC4 was localized to parallel fibers. Along with previous electrophysiological and pharmacological studies, our data indicate that caytaxin plays a critical role in the molecular response of Purkinje cells to climbing fiber input. Caytaxin may also contribute to maturational events in cerebellar cortex.

Caytaxin is also known as BNIP-H where BNIP is the acronym for Bcl-2 nineteen kilodalton interacting protein and H applies to BNIP-2 homology. “Bcl” derives from B-cell lymphoma. BNIP-2 was originally identified as a partner for the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. BNIP-2 contains a protein-protein interaction domain known as the BNIP-2 and Cdc42GAP homology (BCH) domain (Low et al. 2000). Expression of BNIP-2 is associated with Cdc42-dependent morphological changes such as cell elongation and membrane protrusions (Zhou et al. 2005).

Caytaxin may be developmentally regulated by the ubiquitin E3 ligase CHIP (C-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein) which has been shown to polyubiquitinate caytaxin in vitro (Grelle et al. 2006). Another in vitro study suggests that caytaxin may interact with kidney-type glutaminase (KGA) which converts glutamine to glutamate (Buschdorf et al. 2006). Overexpression of caytaxin in PC12 cells relocalized KGA from the mitochondria to neurite terminals. More recently, Buschdorf and colleagues (2008) have shown that caytaxin also interacts with Pin1, a peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase. In vitro, nerve growth factor (NGF) appears to stimulate the interaction of caytaxin with Pin1. Moreover, Pin1 was shown to disrupt caytaxin-KGA complex formation.

Caytaxin may be at the molecular interface between dystonia and ataxia. Caytaxin deficiency is associated with variable degrees of ataxia and dystonia in jittery, hesitant and sidewinder mice. Although caytaxin and associated signaling pathways appear essential for the developmental and/or physiology of cerebellar cortex, the roles of individual network elements (e.g., granule and Purkinje cells) in the pathobiology of dystonia and ataxia have not been delineated. Using RNA derived from cerebellar cortex in toto, we have shown that caytaxin deficiency disrupts phophatidylinositol signaling pathways, calcium homeostasis and extracellular matrix interactions (Xiao et al 2007). However, the relative contributions of pre- and post-synaptic elements, and, similarly, primary and secondary effects on changes in gene expression could not be established given the widespread neuronal distribution of caytaxin during development. In aggregate, currently available data suggest that (1) caytaxin is required for the normal development of Purkinje cells and climbing fiber-Purkinje cell synapses, (2) CHIP may regulate caytaxin levels in adult brain, and (3) the temporal specificity of caytaxin expression in Purkinje and granule cells may determine motoric expressivity (dystonia vs. ataxia).

Other genetic models

Engineered

Vertebrate

Numerous knock-out (KO), knock-in (KI) and transgenic models of DYT1 and other types of dystonia have been generated in mice (Table 2). In addition, Dang et al. (2006) produced a torsinA knock-down model. Many of these models were reviewed by Zhao et al. (2008). Although comprehensive, the list provided in Table 2 does not list all published genetic models of dystonia. Importantly, none of these models manifest dystonia. On the other hand, one or more morphological, neurochemical, behavioral, cellular and neurophysiological abnormalities have been reliably characterized in KO, KI and transgenic models of DYT1 dystonia. The KI models have high etiological validity and some would argue, face validity, given that penetrance of the classic ΔGAG mutation is less than 40%.

Table 2.

Other genetic models

| Human Disorder(s) | Human Gene | Human Protein | Model | Important Results | Reference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered- vertebrate | |||||

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Tor1a-KO mouse | vesicle formation within the nuclear envelope | Goodchild et al. 2005 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | transgenic mouse: human ΔE torsinA CMV promoter | increased striatal dopamine turnover, deficits on a raised beam task, | Sharma et al. 2005, Zhao et al. 2008 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | transgenic mouse: human ΔE torsinA NSE promoter | 40% of mice display an abnormal motor phenotype with circling, self-clasping and hyperactivity; ubiquitin+ perinuclear aggregates in pons; reduced striatal DOPAC/dopamine ratios | Shashidharan et al. 2005 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Torla-Ki mouse | impairments on beam walking task, protein aggregates in the pontine nuclei | Dang et al. 2005 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Torla-KI mouse | homozygotes have vesicles in the nuclear envelope | Goodchild et al. 2005 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Tor1a-knockdown mouse | hyperactivity & increased slips on beam-walking task; reduced striatal DOPAC | Dang et al. 2006 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | transgenic mouse: human ΔE torsinA PrP promoter | hyperactivity & defects on rotarod testing; inclusion formation in brainstem nuclei, nuclear envelope bleb formation; increased brainstem DOPAC | Grundmann et al. 2007 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | cerebral cortex Torla-KO via cross with Emx-cre mice | hyperactivity & increased slips on beam-walking task | Yokoi et al. 2008 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | transgenic mouse: human ΔE torsinA TH promoter | reduced cocaine-induced striatal dopamine, impaired beam walking | Page et al. 2010 |

| DYT8 (PNKD) | MR-1 | myofibrillogenesis regulator | MR-1 transgenic: BAC clones modified to contain A7V and A9V mutations | dystonic attacks precipitated by caffeine and ethanol | Nakayama et al. 2005 |

| DYT11 (MDS) | SGCE | ε-sarcoglycan | Sgce-KO mouse | myoclonus, motor deficits, hyperactivity, anxiety, & depression | Yokoi et al. 2006 |

| SCA27 | FGF14 | fibroblast growth factor-14 | Fgf14-KO mouse | ataxia, paroxysmal dystonia | Shakkottai et al. 2009 |

| Engineered-invertebrate | |||||

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Drosophila-transgenic overexpression ΔGAG human torsinA | enlarged boutons neuromuscular junction, disruption of TGF-β signaling | Koh et al. 2004 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | Drosophila-RNAi downregulation of torp4A | progressive retinal degeneration | Muraro & Moffat 2006 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | C. elegons-transgenic overexpression of human torsinA | reduction in polyglutamine repeat-induced protein aggregation | Caldwell et al. 2003 |

| DYT1 | TOR1A | torsinA | C. elegans-ges-1 intestinal promoter transgenic expression of WT and mutant human torsinA | torsinA mutations (ΔE torsinA, reduced ATPase activity, other) increase sensitivity to endoplasmic reticulum stress | Chen et al. 2010 |

Abbreviations: DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; KI, knock-in; KO, knock-out; MDS, myoclonus-dystonia syndrome; MR-1, myofibrillogenesis regulator; PNKD, paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia; PrP, prion protein; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; WT, wild-type

Sharma and colleagues (2005) developed three transgenic models to study DYT1 dystonia: human mutant torsinA 1 (hMT1), human mutant torsinA 2 (hMT2) and human wild-type torsinA (hWT). The hMT2 and hWT mice exhibit weak expression of their transgenes (Sharma et al. 2005, Zhao et al. 2008). In contrast, hMT1 mice express transgene 3.90–4.95× higher than human brain (Zhao et al. 2008). The hMT1 torsinA transgenic mouse developed by Sharma and colleagues (2005) shows impaired amphetamine-induced dopamine release (Balcioglu et al. 2007), increased striatal dopamine turnover (Zhao et al. 2008), impaired beam walking (Zhao et al. 2008), increased hind-base widths (Zhao et al. 2008), impaired bidirectional synaptic plasticity (Martella et al. 2009) and reduced activity of the dopamine transporter (Hewett et al. 2010). No abnormalities of the nuclear envelope have been detected in the hMT1 mouse model (Zhao et al. 2008).

Martella and colleagues (2009) reported that long-term depression (LTD) could not be elicited in medium spiny neurons from hMT1 mice. Moreover, long-term potentiation (LTP) in medium spiny neurons was enhanced in hMT1 mice in comparison to wild-type littermates. LTD was rescued in hMT1 medium spiny neurons either by lowering endogenous levels of acetylcholine or exposure to a muscarinic antagonist. In related work, a dopamine agonist, quinpirole, caused membrane depolarization and increase firing rates in striatal cholinergic interneurons from hMT1 mice (Pisani et al. 2006). In aggregate, these electrophysiological and neurochemical findings point out an imbalance between dopaminergic and cholinergic signaling in DYT1 dystonia.

Homozygous, but not heretozygous, KO and KI models exhibit structural abnormalities of the nuclear envelope (Goodchild et al. 2005). Morphological studies in other DYT1 models have shown evidence of torsinA- and ubiquitin-positive cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Shashidharan et al. 2004, Dang et al. 2005, Grundmann et al. 2007) and bleb formation at the nuclear envelope (Grundmann et al. 2007).

Recent models have been engineered to explore the role of specific brain regions and pathways in the pathobiology of DYT1 dystonia (Yokoi et al. 2008, Page et al. 2010). Yokoi and colleagues (2008) generated a cerebral cortex-specific DYT1 conditional KO mice by mating Tor1a-loxP mice with Emx1-cre KI mice. The conditional KO mice showed normal development of barrel fields in somatosensory cortex, hyperactivity and increased slips on a beam-walking task. Given the potential role of dopaminergic neurotransmission in DYT1 dystonia, Page and co-workers (2010) expressed human wild-type torsinA and ΔE-torsinA in mice under control of the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter. Expression of mutant and wild-type torsinA was limited to dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain (Page et al. 2010). There was no detectable change in striatal dopamine turnover. However, defective dopamine release was detected with microdialysis and fast cycle voltammetry. Similar to KI and other transgenic models, the TH-ΔE-torsinA mice exhibited increased slips on a beam-walking task.

Models of paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia (DYT8) and myoclonus-dystonia syndrome (MDS/DYT11) have been generated and show many features of the corresponding human disorders. However the DYT11 model developed by Yokoi and colleagues (2006) does not manifest dystonia. A mouse model of SCA27 exhibits paroxysmal dystonia. Unfortunately, additional study of the DYT8 and DYT11 models has been lacking. As such, the underlying neurophysiological underpinnings of the corresponding movement disorders remain largely unknown.

Invertebrate

The fruit fly and roundworm provide viable tools for studying the in vivo cellular biology of movement and neurodegenerative disorders. Both, for example, harbor well-defined collections of dopaminergic neurons. Studies in invertebrates have contributed to our understanding of torsinA biology. For instance, Caldwell and colleagues (2003) provided evidence that torsinA plays a chaperone role by showing that overexpression of both human and C. elegans torsin proteins reduces polyglutamine-dependent protein aggregation. Expression of ΔE torsinA in flies caused temperature-dependent locomotor deficits, enlarged boutons at neuromuscular junctions and possible defects in TGF-β signaling (Koh et al. 2004). Of note, overexpression of Smad2, a downstream effector of the TGF-β signaling pathway, suppressed motoric and ultrastructural defects in the ΔE-torsinA flies.

Chen and colleagues (2010) used C. elegans to test the hypothesis that selective defects in torsinA function would result in increased vulnerability to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Their analyses showed that torsinA normally serves a protective function to maintain a homeostatic threshold against ER stress. Loss of torsinA or mutations that limit its translocation to the ER or block ATPase activity were shown to impair the ER stress response.

Invertebrate model systems, particularly C. elegans, also facilitate high-throughput testing of candidate drugs targeting specific biological processes. Just recently, the first screen for candidate small molecule therapeutics for dystonia was completed in C. elegans (Cao et al. 2010). Two classes of antibiotics, quinolines and aminopenicillins, were found to enhance activity of wild-type torsinA. In downstream corroborative analyses, a motoric defect in ΔE torsinA knock-in mice was rescued by systemic administration of ampicillin.

Spontaneous mutants

Rodents, mainly spontaneously mutant mice with movement disorders, have revealed molecules and cellular pathways involved in motor control. Examples of deficient or defective proteins in mice with motor dysfunction (ataxia and/or dystonia) include the type VIII alpha subunit of voltage-gated sodium channel in MedJ mice (Burgess et al. 1995), delta2 glutamate receptor in lurcher mice (Zuo et al. 1997), potassium inwardly-rectifying channel subfamily J member 6 in weaver mice (Patil et al. 1995), ATP/GTP binding protein 1 in Purkinje cell degeneration mice (Fernandez-Gonzalez et al. 2002), and P/Q type calcium channel α-1A subunit in tottering mice (Fletcher et al. 1996). Several rodents with spontaneous mutations manifest dystonia as a core feature of their motor phenotypes (Table 3). Genetically engineered mice may, sometimes unexpectedly, also exhibit dystonia. For instance, an FGF14 knock-out mouse (Table 2) was found to manifest paroxysmal dystonia along with interictal ataxia (Wang et al. 2002).

Table 3.

Spontaneous mutants

| Model | Human Disorder(s) | Gene | Protein | Function of Encoded Protein | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dystonia musculorum mouse | epidermolysis bullosa simplex (epithelial isoform) | BPAG1 | neural isoform bullous pemphigoid antigen | hemi-desmosomal protein | Brown et al. 1995 |

| dtsz hamster | unknown | unknown | unknown | Richter et al. 1991 | |

| Tottering mouse | SCA6, FHM, EA-2 | CANCA1A | α1A calcium channel | calcium channel | Fureman et al. 2002 |

| Stargazer mouse | chronic neuropathic pain | CACNG2 | γ2 calcium channel subunit | calcium channel | Leitch et al. 2009 |

| Opisthotonus mouse | SCA15/SCA16 | ITPR1 | inositol triphosphate receptor 1 (IP3R1) | intracellular calcium homeostasis | Novak et al. 2010 |

| hph-1 mouse | DYT5 (doparesponsive dystonia) | unknown | GTP cyclohydrolase type 1 | rate-limiting enzyme for synthesis of BH4 | Hyland et al. 2003 |

| Ducky mouse | CACNA2D2 | α2δ calcium channel subunit | calcium channel | Donato et al. 2006 | |

| Lethargic mouse | epilepsy | CACNB4 | β4 calcium channel subunit | calcium channel | Devanagondi et al. 2007 |

| Waddles mouse | quadrupedal gait | CAR8 | carbonic anhydrase-related protein type VIII | intracellular calcium homeostasis via IP3R1 binding | Jiao et al. 2005, Turkmen et al. 2009 |

| Wriggle mouse Sagami | PMCA2 | plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase | calcium transport | Takahashi et al. 1999 | |

| Myshkin (Myk) mouse | DYT12 (rapid-onset dystonia Parkinsonism) | ATP1A3 | Na+-K+-ATPase α3 isoform | Na+-K+-ATPase | Clapcote et al. 2009 |

Abbreviations: BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; EA-2, episodic ataxia type 2; FHM, familial hemiplegic migraine; SCA6, spinocerebellar ataxia type 6;

All of the mutations listed in Table 3 are autosomal recessive although the causal mutations have not been identified in the dtSZ hamster or hph-1 mouse. Review of Table 3 reveals that virtually all genes associated with dystonia in spontaneous mutants are involved in Purkinje cell calcium signaling. For example, deficiency of carbonic anhydrase type VIII (CAR8) produces a distinctive lifelong gait disorder in waddles mice (Jiao et al. 2005) and quadrupedal gait in humans (Türkmen et al. 2009). Although CAR8 lacks catalytic activity, it does reduce the affinity of IP3R1 for IP3. CAR8 is concentrated in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Jiao et al. 2005). Consequently, CAR8 deficiency is predicted to cause motor dysfunction by altering calcium homeostasis and disrupting the normal physiology of Purkinje cells. Similar consequences could also be attributed to deficiency of IP3R1 and PMCA2. As is the case for caytaxin, CAR8 and other Purkinje cell proteins associated with dystonia may contribute to the normal ultrastructural maturation of cerebellar cortex (Hirasawa et al. 2007).

Pharmacological and neural lesion models

Models generated with wild-type animals have proven useful for identifying neural structures from which dystonia may arise. Table 4 lists many of the most informative models that have been described I the refereed literature. Generalized and segmental dystonia can be generated via manipulations of the cerebellum, red nucleus and basal ganglia (Table 4). In contrast, hand-forearm dystonia has been associated with dedifferentiation of somatosensory cortex, and abnormal head-neck postures can be produced by lesions or stimulation of the midbrain, particularly the interstitial nucleus of Cajal. Although there is no consensus regarding specific neuroanatomical sites of origin, animal models of the focal dystonias (blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, and hand-forearm dystonia) suggest that maladaptive sensorimotor integration may be a pathophysiological event common to all of the dystonias.

Table 4.

Pharmacological and neural lesion models

| Disorder modeled | Species | Lesion/treatment | Key features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal dystonia | ||||

| blepharospasm | rat | partial unilateral 6-OHDA lesion of the SNpc & partial unilateral denervation of the orbicularis oculi muscle | blepharospasm | Schicatano et al. 1997 |

| unilateral hemifacial spasm/blepharospasm | cat | unilateral injection of serotonin into the facial motor nucleus | unilateral blepharospasm/hemifacial spasm | LeDoux et al. 1998 |

| cervical dystonia | monkey | electrolytic lesions-medial midbrain tegmentum | contraversive torticollis | Foltz et al. 1959 |

| cervical dystonia | monkey | lesions of mesencephalic tegmentum | ipsiversive torticollis | Battista et al. 1976 |

| cervical dystonia | monkey | microstimulation interstitial nucleus of Cajal | ipsiversive head rotation | Klier et al. 2002 |

| cervical dystonia | monkey (marmoset) | 6-OHDA lesion ascending nigrostriatal pathway | ipsiversive torticollis that resolved with apomorphine | Sambrook et al. 1979 |

| writer's cramp | monkey | intensive sensorimotor training | hand-forearm dystonia | Byl et al. 1996 |

| Generalized dystonia | mouse | injection of kainic acid into cerebellar cortex | severe truncal and appendicular dystonia | Pizoli et al. 2002 |

| mouse | systemic administration of L-type calcium channel agonists | severe truncal and appendicular dystonia | Jinnah et al. 2000 | |

| rat | injection of sigma receptor ligands into the red nucleus | cervical and truncal dystonia | Walker et al. 1988 | |

| rabbit | fetal hypoxia-ischemia | mixed dystonia-spasticity | Derrick et al. 2004 | |

| mouse/rat | systemic 3-nitropropionic acid | mild dystonia, bradykinesia | Guyot et al. 1997 | |

Studies of blepharospasm by Evinger and colleagues have been particularly informative (Schicatano et al. 1997, Peshori et al. 2001). In brief, a two-factor model may explain the origin of blepharospasm. The first factor is subclinical reduction in striatal dopamine, which typically occurs with normal aging. Reduced striatal dopamine may be associated with increases in trigeminal blink excitability and duration. The second factor is an external ophthalmic insult such as dry eye. This model is compatible with age-of-onset and ocular co-morbidities in humans with blepharospasm (Hallett et al. 2008).

Conclusions

Largely precipitated by work in animal models, a role for the cerebellum in the pathophysiology of human dystonia has received increasing attention in recent years (Jinnah and Hess 2006, Perlmutter and Thach 2007, Argyelan et al. 2009) and is supported by data from a variety of clinical fronts: lesion localization in secondary cervical dystonia (LeDoux and Brady 2003), functional imaging studies in DYT1 dystonia (Eidelberg et al. 1998), the syndrome of dystonia with cerebellar atrophy (DYTCA) (Le Ber et al. 2006), and dystonia as a presenting or prominent feature of several hereditary ataxias. LeDoux and Brady (2003) showed that structural lesions associated with secondary cervical dystonia were commonly localized to the cerebellum and its afferents. The cerebellum also contributes to primary dystonias. Using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography, similar patterns of hypermetabolism were detected in both manifesting and nonmanifesting carriers of DYT1 mutations (Eidelberg et al. 1998). In movement-free conditions, both manifesting and non-manifesting carriers showed increased metabolic activity in the lentiform nuclei, cerebellum, and supplementary motor areas. In movement-related conditions, manifesting carriers showed increased metabolic activity in the midbrain, cerebellum, and thalamus. Le Ber and colleagues (2006) coined the acronym DYTCA for familial syndromes with the combination of dystonia and mild slowly-progressive ataxia. Their 12 patients from 8 families displayed appendicular dystonia, often with spasmodic dysphonia. Some subjects also had cervical or facial dystonia. Similar series of patients had been previously reported by Fletcher et al. (1988) and Kuoppamaki et al. (2003). These reports suggest that both ataxia AND dystonia may arise from defective olivocerebellar pathways in humans. Moreover, some of these cases could be allelic with Cayman ataxia, with phenotypic differences being due to genetic background and type of mutation (e.g., missense vs. splice site).

In coming years it is quite likely that genetic/molecular etiologies will be identified for an ever increasing percentage of primary dystonia cases. In this context, it is important to recognize that the current clinical definition of dystonia may preclude unification of molecular etiologies. Similarly, there may be no universal “upstream” signature circuit abnormality common to all the dystonias. Simply put, dystonia may be a relatively common downstream manifestation of a variety of hereditary and acquired insults to the nervous system. Despite these caveats, some common ground is likely and animal models should contribute to identification of genetic causes of human disorders, understanding disease pathogenesis and pinpointing neural network abnormalities to guide neurosurgical intervention. Moreover, animal models may be used to develop preventative treatments in individuals with pathological allelic variants and small molecule pharmacotherapeutics in subjects with manifest disease. It should be emphasized that rigorous study of select hereditary dystonias may provide insight into the pathobiology of the more common sporadic dystonias. For case in point, work with the dt rat has contributed to our understanding of motor systems by showing that abnormal signaling in cerebellar cortex can lead to abnormal cerebellar output with bursting firing patterns in cerebellar output. As a result, neuromodulation of cerebellar cortex and/or the cerebellar nuclei may be rediscovered as targets for functional neurosurgery in patients with dystonia. In summation, integration of data from animal models and functional imaging in humans suggests that maladaptive sensorimotor learning secondary to developmental defects in cerebellar cortex as a consequence of impaired calcium homeostasis in Purkinje cells contributes to the pathogenesis of adult-onset primary dystonia. It is also possible that the manifestation of dystonia requires interactions among pathological olivocerebellar and striatal circuits (Neychev et al. 2008).

Acknowledgements

Dr. LeDoux's work on dystonia and the dystonic rat have been supported by the NIH (K08NS001593, R03NS050185, R01NS048458, R01NS069936 and U54NS065701), Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Neuroscience Institute, Bachmann-Strauss Dystonia & Parkinson Foundation, and Parkinson's and Movement Disorder Foundation. Many thanks go to Jianfeng Xiao, Yu Zhao and Kate Marshall for review and critique of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCE LIST

- Argyelan M, Carbon M, Niethammer M, Ulug AM, Voss HU, Bressman SB, et al. Cerebellothalamocortical connectivity regulates penetrance in dystonia. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9740–9747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2300-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu A, Kim MO, Sharma N, Cha JH, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Dopamine release is impaired in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista AF, Goldstein M, Miyamoto T, Matsumoto Y. Effect of centrally acting drugs on experimental torticollis in monkeys. Adv. Neurol. 1976;14:329–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beales M, Lorden JF, Walz E, Oltmans GA. Quantitative autoradiography reveals selective changes in cerebellar GABA receptors of the rat mutant dystonic. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:1874–1885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-06-01874.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomar JM, Benke PJ, Slattery EL, Puttagunta R, Taylor LP, Seong E, et al. Mutations in a novel gene encoding a CRAL-TRIO domain cause human Cayman ataxia and ataxia/dystonia in the jittery mouse. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:264–269. doi: 10.1038/ng1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Bernier G, Mathieu M, Rossant J, Kothary R. The mouse dystonia musculorum gene is a neural isoform of bullous pemphigoid antigen 1. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:301–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DL, Kohrman DC, Galt J, Plummer NW, Jones JM, Spear B, et al. Mutation of a new sodium channel gene, Scn8a, in the mouse mutant `motor endplate disease'. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:461–465. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschdorf JP, Chew LL, Soh UJ, Liou YC, Low BC. Nerve growth factor stimulates interaction of Cayman ataxia protein BNIP-H/Caytaxin with peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 in differentiating neurons. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschdorf JP, Li Chew L, Zhang B, Cao Q, Liang FY, Liou YC, et al. Brain-specific BNIP-2-homology protein Caytaxin relocalises glutaminase to neurite terminals and reduces glutamate levels. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:3337–3350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byl NN, Mezenich MM, Jenkins WM. A primate genesis model of focal dystonia and repetitive strain injury: I. Learning-induced dedifferentiation of the representation of the hand in the primary somatosensory cortex in adult monkeys. Neurology. 1996;47:508–520. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell GA, Cao S, Sexton EG, Gelwix CC, Bevel JP, Caldwell KA. Suppression of polyglutamine-induced protein aggregation in Caenorhabditis elegans by torsin proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:307–319. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Hewett JW, Yokoi F, Lu J, Buckley AC, Burdette, et al. Chemical enhancement of torsinA function in cell and animal models of torsion dystonia. Dis. Model Mech. 2010;3:386–396. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Burdette AJ, Porter JC, Ricketts JC, Fox SA, Nery FC, et al. The early-onset torsion dystonia-associated protein, torsinA, is a homeostatic regulator of endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:3502–3515. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapcote SJ, Duffy S, Xie G, Kirshenbaum G, Bechard AR, Rodacker Shack V, et al. Mutation I810N in the alpha3 isoform of Na+,K+-ATPase causes impairments in the sodium pump and hyperexcitability in the CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:14085–14090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904817106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Pence MA, Li Y. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in Dyt1 knockdown mice. Neurosci. Res. 2006;56:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vente J, Asan E, Gambaryan S, Markerink-van Ittersum M, Axer H, Gallatz K. Localization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase type II in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2001;108:27–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick M, Luo NL, Bregman JC, Jilling T, Ji X, Fisher K, et al. Preterm fetal hypoxia-ischemia causes hypertonia and motor deficits in the neonatal rabbit: a model for human cerebral palsy? J. Neurosci. 2004;24:24–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2816-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanagondi R, Egami K, LeDoux MS, Hess EJ, Jinnah HA. Neuroanatomical substrates for paroxysmal dyskinesia in lethargic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;27:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R, Page KM, Koch D, Nieto-Rostro M, Foucault I, Davies A, et al. The ducky(2J) mutation in Cacna2d2 results in reduced spontaneous Purkinje cell activity and altered gene expression. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12576–12586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3080-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelberg D, Moeller JR, Antonini A, Kazumata K, Nakamura T, Dhawan V, et al. Functional brain networks in DYT1 dystonia. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:303–312. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez A, La Spada AR, Treadaway J, Higdon JC, Harris BS, Sidman RL, et al. Purkinje cell degeneration (pcd) phenotypes caused by mutations in the axotomy-induced gene, Nna1. Science. 2002;295:1904–1906. doi: 10.1126/science.1068912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher CF, Lutz CM, O'Sullivan TN, Shaughnessy JD, Jr., Hawkes R, Frankel WN, et al. Absence epilepsy in tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 1996;87:607–617. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher NA, Stell R, Harding AE, Marsden CD. Degenerative cerebellar ataxia and focal dystonia. Mov. Disord. 1988;3:336–342. doi: 10.1002/mds.870030410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz EL, Knopp LM, Ward AA., Jr. Experimental spasmodic torticollis. J. Neurosurg. 1959;16:55–67. doi: 10.3171/jns.1959.16.1.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fureman BE, Jinnah HA, Hess EJ. Triggers of paroxysmal dyskinesia in the calcium channel mouse mutant tottering. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002;73:631–637. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Bomar JM, Burmeister M, Moran JV. Characterization of a mutagenic B1 retrotransposon insertion in the jittery mouse. Hum. Mutat. 2004;24:9–13. doi: 10.1002/humu.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild RE, Kim CE, Dauer WT. Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron. 2005;48:923–932. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelle G, Kostka S, Otto A, Kersten B, Genser KF, Muller EC, et al. Identification of VCP/p97, carboxyl terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP), and amphiphysin II interaction partners using membrane-based human proteome arrays. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:234–244. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500198-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann K, Reischmann B, Vanhoutte G, Hubener J, Teismann P, Hauser TK, et al. Overexpression of human wildtype torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;27:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot MC, Hantraye P, Dolan R, Palfi S, Maziere M, Brouillet E. Quantifiable bradykinesia, gait abnormalities and Huntington's disease-like striatal lesions in rats chronically treated with 3-nitropropionic acid. Neuroscience. 1997;79(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett M, Evinger C, Jankovic J, Stacy M. Update on blepharospasm: report from the BEBRF International Workshop. Neurology. 2008;71(16):1275–1282. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327601.46315.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett J, Johanson P, Sharma N, Standaert D, Balcioglu A. Function of dopamine transporter is compromised in DYT1 transgenic animal model in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2010;113:228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa M, Xu X, Trask RB, Maddatu TP, Johnson BA, Naggert JK, et al. Carbonic anhydrase related protein 8 mutation results in aberrant synaptic morphology and excitatory synaptic function in the cerebellum. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland K, Gunasekara RS, Munk-Martin TL, Arnold LA, Engle T. The hph-1 mouse: a model for dominantly inherited GTP-cyclohydrolase deficiency. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54(Suppl 6):S46–48. doi: 10.1002/ana.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn RC, Majerus PW. Properties of inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:14559–14565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Yan J, Zhao Y, Donahue LR, Beamer WG, Li X, et al. Carbonic anhydrase-related protein VIII deficiency is associated with a distinctive lifelong gait disorder in waddles mice. Genetics. 2005;171:1239–1246. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah HA, Sepkuty JP, Ho T, Yitta S, Drew T, Rothstein JD, et al. Calcium channel agonists and dystonia in the mouse. Mov. Disord. 2000;15:542–551. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200005)15:3<542::AID-MDS1019>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah HA, Hess EJ, LeDoux MS, Sharma N, Baxter MG, Delong MR. Rodent models for dystonia research: characteristics, evaluation, and utility. Mov. Disord. 2005;20:283–292. doi: 10.1002/mds.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnah HA, Hess EJ. A new twist on the anatomy of dystonia: the basal ganglia and the cerebellum? Neurology. 2006;67:1740–1741. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000246112.19504.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfhamer D, Sweet HO, Sufalko D, Warren S, Johnson KR, Burmeister M. The neurological mouse mutations jittery and hesitant are allelic and map to the region of mouse chromosome 10 homologous to 19p13.3. Genomics. 1996;35:533–538. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier EM, Wang H, Constantin AG, Crawford JD. Midbrain control of three-dimensional head orientation. Science. 2002;295:1314–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.1067300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TW, Verstreken P, Bellen HJ. Dap160/intersectin acts as a stabilizing scaffold required for synaptic development and vesicle endocytosis. Neuron. 2004;43:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppamaki M, Giunti P, Quinn N, Wood NW, Bhatia KP. Slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia and cervical dystonia: clinical presentation of a new form of spinocerebellar ataxia? Mov. Disord. 2003;18:200–206. doi: 10.1002/mds.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ber I, Clot F, Vercueil L, Camuzat A, Viemont M, Benamar N, et al. Predominant dystonia with marked cerebellar atrophy: a rare phenotype in familial dystonia. Neurology. 2006;67:1769–1773. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244484.60489.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Lorden JF, Ervin JM. Cerebellectomy eliminates the motor syndrome of the genetically dystonic rat. Exp. Neurol. 1993;120:302–310. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Lorden JF, Meinzen-Derr J. Selective elimination of cerebellar output in the genetically dystonic rat. Brain Res. 1995;697:91–103. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00792-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Hurst DC, Lorden JF. Single-unit activity of cerebellar nuclear cells in the awake genetically dystonic rat. Neuroscience. 1998;86:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Lorden JF. Abnormal spontaneous and harmaline-stimulated Purkinje cell activity in the awake genetically dystonic rat. Exp. Brain. Res. 2002;145:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux MS, Brady KA. Secondary cervical dystonia associated with structural lesions of the central nervous system. Mov. Disord. 2003;18:60–69. doi: 10.1002/mds.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch B, Shevtsova O, Guevremont D, Williams J. Loss of calcium channels in the cerebellum of the ataxic and epileptic stargazer mutant mouse. Brain Res. 2009;1279:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Muhlethaler M. Electrophysiology of guinea-pig cerebellar nuclear cells in the in vitro brain stem-cerebellar preparation. J. Physiol. 1988;404:241–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorden JF, McKeon TW, Baker HJ, Cox N, Walkley SU. Characterization of the rat mutant dystonic (dt): a new animal model of dystonia musculorum deformans. J. Neurosci. 1984;4:1925–1932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-08-01925.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorden JF, Oltmans GA, McKeon TW, Lutes J, Beales M. Decreased cerebellar 3',5'-cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels and insensitivity to harmaline in the genetically dystonic rat (dt) J. Neurosci. 1985;5:2618–2625. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-10-02618.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorden JF, Lutes J, Michela VL, Ervin J. Abnormal cerebellar output in rats with an inherited movement disorder. Exp. Neurol. 1992;118:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90026-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low BC, Seow KT, Guy GR. The BNIP-2 and Cdc42GAP homology domain of BNIP-2 mediates its homophilic association and heterophilic interaction with Cdc42GAP. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37742–37751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutes J, Lorden JF, Davis BJ, Oltmans GA. GABA levels and GAD immunoreactivity in the deep cerebellar nuclei of rats with altered olivo-cerebellar function. Brain Res. Bull. 1992;29:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella G, Tassone A, Sciamanna G, Platania P, Cuomo D, Viscomi MT, et al. Impairment of bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the striatum of a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia: role of endogenous acetylcholine. Brain. 2009;132:2336–2349. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeon TW, Lorden JF, Oltmans GA, Beales M, Walkley SU. Decreased catalepsy response to haloperidol in the genetically dystonic (dt) rat. Brain Res. 1984;308:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90920-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraro NI, Moffat KG. Down-regulation of torp4a, encoding the Drosophila homologue of torsinA, results in increased neuronal degeneration. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:1338–1353. doi: 10.1002/neu.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naudon L, Delfs JM, Clavel N, Lorden JF, Chesselet MF. Differential expression of glutamate decarboxylase messenger RNA in cerebellar Purkinje cells and deep cerebellar nuclei of the genetically dystonic rat. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neychev VK, Fan X, Mitev VI, Hess EJ, Jinnah HA. The basal ganglia and cerebellum interact in the expression of dystonic movement. Brain. 2008;131:2499–2509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak MJ, Sweeney MG, Li A, Treacy C, Chandrashekar HS, Giunti P, et al. An ITPR1 gene deletion causes spinocerebellar ataxia 15/16: A genetic, clinical and radiological description. Mov. Disord. 2010;25:2176–2182. doi: 10.1002/mds.23223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmans GA, Beales M, Lorden JF. Glutamic acid decarboxylase activity in micropunches of the deep cerebellar nuclei of the genetically dystonic (dt) rat. Brain Res. 1986;385:148–151. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Bao L, Andre P, Pelta-Heller J, Sluzas E, Gonzalez-Alegre P, et al. Cell-autonomous alteration of dopaminergic transmission by wild type and mutant (DeltaE) TorsinA in transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagabko C, Morley S, Hernandez M, Cassolato P, Gordon H, Parsons, et al. Ligand specificity in the CRAL-TRIO protein family. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6467–6474. doi: 10.1021/bi034086v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N, Cox DR, Bhat D, Faham M, Myers RM, Peterson AS. A potassium channel mutation in weaver mice implicates membrane excitability in granule cell differentiation. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:126–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JS, Thach WT. Writer's cramp: questions of causation. Neurology. 2007;69:331–332. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269330.95232.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshori KR, Schicatano EJ, Gopalaswamy R, Sahay E, Evinger C. Aging of the trigeminal blink system. Exp. Brain Res. 2001;136:351–363. doi: 10.1007/s002210000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Martella G, Tscherter A, Bonsi P, Sharma N, Bernardi G, Standaert DG. Altered responses to dopaminergic D2 receptor activation and N-type calcium currents in striatal cholinergic interneurons in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;24:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizoli CE, Jinnah HA, Billingsley ML, Hess EJ. Abnormal cerebellar signaling induces dystonia in mice. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7825–7833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07825.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter A, Fredow G, Loscher W. Antidystonic effects of the NMDA receptor antagonists memantine, MK-801 and CGP 37849 in a mutant hamster model of paroxysmal dystonia. Neurosci. Lett. 1991;133:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90056-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook MA, Crossman AR, Slater P. Experimental torticollis in the marmoset produced by injection of 6-hydroxydopamine into the ascending nigrostriatal pathway. Exp. Neurol. 1979;63:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicatano EJ, Basso MA, Evinger C. Animal model explains the origins of the cranial dystonia benign essential blepharospasm. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2842–2846. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakkottai VG, Xiao M, Xu L, Wong M, Nerbonne JM, Ornitz DM, et al. FGF14 regulates the intrinsic excitability of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;33:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Baxter MG, Petravicz J, Bragg DC, Schienda A, Standaert DG, et al. Impaired motor learning in mice expressing torsinA with the DYT1 dystonia mutation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5351–5355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0855-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Sandu D, Potla U, Armata IA, Walker RH, McNaught KS, et al. Transgenic mouse model of early-onset DYT1 dystonia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:125–133. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton S. Neurophysiological and neuroanatomical investigations of the olivo-cerebellar system in the mutant rat dystonic (dt) University of Alabama at Birmingham; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton SE, Lorden JF. Effect of harmaline on cells of the inferior olive in the absence of tremor: differential response of genetically dystonic and harmaline-tolerant rats. Neuroscience. 1991;41:543–549. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90347-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Kitamura K. A point mutation in a plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase gene causes deafness in Wriggle Mouse Sagami. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;261:773–778. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkmen S, Guo G, Garshasbi M, Hoffmann K, Alshalah AJ, Mischung C, et al. CA8 mutations cause a novel syndrome characterized by ataxia and mild mental retardation with predisposition to quadrupedal gait. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(5):e1000487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JM, Matsumoto RR, Bowen WD, Gans DL, Jones KD, Walker FO. Evidence for a role of haloperidol-sensitive sigma-`opiate' receptors in the motor effects of antipsychotic drugs. Neurology. 1988;38:961–965. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Bardgett ME, Wong M, Wozniak DF, Lou J, McNeil BD, et al. Ataxia and paroxysmal dyskinesia in mice lacking axonally transported FGF14. Neuron. 2002;35:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Gong S, LeDoux MS. Caytaxin deficiency disrupts signaling pathways in cerebellar cortex. Neuroscience. 2007;144:439–461. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, LeDoux MS. Caytaxin deficiency causes generalized dystonia in rats. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;141:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi F, Dang MT, Li J, Li Y. Myoclonus, motor deficits, alterations in emotional responses and monoamine metabolism in epsilon-sarcoglycan deficient mice. J. Biochem. 2006;140:141–146. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, DeCuypere M, LeDoux MS. Abnormal motor function and dopamine neurotransmission in DYT1 DeltaGAG transgenic mice. Exp. Neurol. 2008;210:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YT, Guy GR, Low BC. BNIP-2 induces cell elongation and membrane protrusions by interacting with Cdc42 via a unique Cdc42-binding motif within its BNIP-2 and Cdc42GAP homology domain. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;303:263–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziefer P, Leung J, Razzano T, Shalish C, LeDoux MS, Lorden JF, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of rat torsinA in the normal and genetically dystonic (dt) rat. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2002;101:132–135. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, De Jager PL, Takahashi KA, Jiang W, Linden DJ, Heintz N. Neurodegeneration in Lurcher mice caused by mutation in delta2 glutamate receptor gene. Nature. 1997;388:769–773. doi: 10.1038/42009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]