Abstract

Investigating children’s outdoor play unites scholarship on neighborhoods, parental perceptions of safety, and children’s health. Utilizing the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study (N=3,448), we examine mothers’ fear of their five-year-old children playing outdoors, testing associations with neighborhood social characteristics, city-level crime rates, maternal mental health, and social support. Living in public housing, perceptions of low neighborhood collective efficacy, and living in a Census tract with a higher proportion of Blacks and households in poverty are associated with higher odds of maternal fear, but crime rates are not a significant predictor of fear. We also demonstrate that not being depressed – but not social support or collective efficacy – buffers the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fears of outdoor play.

Keywords: Child Well-being, Mental Health, Neighborhoods, Parenting

Children’s outdoor play is an important indicator of overall healthy development (Burdette & Whitaker, 2005a; Ginsburg, 2007), and scholars have increasingly called for analysis of the multidimensional factors associated with young children’s activity levels; yet few such studies exist (Papas et al., 2007). Children’s outdoor activities have declined in recent decades (Burdette & Whitaker, 2005a; Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001), at the same time as an increase in Americans’ fear of crime, particularly in urban areas (Liska & Baccaglini, 1990; Warr & Stafford, 1982). Connecting these two phenomena, Clements (2004) found that over three quarters of mothers cite safety and crime concerns when explaining why they prevent their children from playing outdoors. Concerns about safety occur across socioeconomic categories, but are especially prevalent for mothers living in high-poverty areas (Timperio, Salmon, Tedford, & Crawford, 2005; Weir, Etelson, & Brand, 2006). Urban mothers, particularly those living in high-poverty neighborhoods, may be especially likely to be fearful of their children playing outdoors; yet maternal and family characteristics associated with this fear, as well as potential characteristics which may buffer the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear, have received little attention. We use data from a large, nationally representative birth cohort study of urban children to examine how individual and neighborhood-level factors, as well as city-level crime rates, influence mothers’ fear of allowing their children to play outside; and examine whether social support, neighborhood collective efficacy (a sense of reciprocal norms and trust among neighbors), and maternal mental health may buffer the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear.

Neighborhoods and Children’s Outdoor Play

Recently, scholars have begun exploring the neighborhood factors associated with children’s activity levels (Franzini et al., 2009). Much of this scholarship has focused on the effects of parental perceptions of neighborhood safety (Carver, Timperio, & Crawford, 2008; Davison & Lawson, 2006; Gable, Chang, & Krull, 2007; Lumeng, Appugliese, Cabral, Bradley, & Zuckerman, 2006; Timperio et al., 2005; Weir et al., 2006), along with crime and poorly lit streets (Rose & Richards, 2007) and built environment conditions such as park safety (Sallis & Glanz, 2006; Singh, Siahpush & Kogan, 2010), and this literature has largely agreed that children in more disordered neighborhoods, which parents perceive as unsafe, tend to be less active. Yet not all parents who live in poor, disordered neighborhoods are afraid to let their children play outside, and at least one study found that parental perceptions of safety had no significant effect on three-year-old children’s levels of outdoor play (Burdette & Whittaker, 2005b), which may be because the relationship only emerges as children get older. Another recent study demonstrated that children in public housing, despite mothers’ concerns about safety, spent more time playing outside (Kimbro, Brooks-Gunn, & McLanahan, 2011). All together, this research suggests that while neighborhood disorder exerts a strong influence on maternal fear, certain factors may be able to buffer this influence on mothers’ fears of children playing outdoors.

Fear of Crime

Scholarship on fear of crime, a measure most commonly utilized in criminology research (for example, Warr & Ellison, 2000), has found it to capture individuals’ perceptions of danger but also to be influenced by more general neighborhood conditions (Carvalho & Lewis, 2003), as well as tapping into the emotions associated with neighborhood violence, compared to questions about safety itself which parents may answer more specifically or objectively (Carver, Timperio, Hesketh, & Crawford, 2010). Additionally, scholarship on altruistic fear—fear for others—has been shown to elicit even stronger reactions and behavior changes compared to fear for oneself (Snedker, 2006; Warr & Ellison, 2000). Also, women are more likely than men to report fear of crime, a finding which has been replicated numerous times (e.g., Scarborough, Like-Haislip, Novak, Lucas, & Alarid, 2010; Schafer, Huebner, & Bynum, 2006), and Wyant (2008) proposed that women may feel more vulnerable to crime because they are more physically vulnerable, despite statistically being at low risk for violence. It is likely that this vulnerability response extends to mothers’ fears for their children, and previously identified parental responses to neighborhood violence include: avoiding certain neighborhood locations (Brodsky, 1996); identifying safe spaces (Furstenberg, 1993); completing activities at certain times of the day (Burton & Graham, 1998); requiring older siblings to accompany younger children (Jarrett, 1998); and avoiding certain individual neighbors and seeking out others (Puntenney, 1997). In other words, it is clear that fear of violence can have significant consequences for parenting strategies and choices, and also that these fears can be affected by mothers’ emotional states in addition to their actual level of risk of victimization.

Theoretical Framework

Harding (2009) and other neighborhood scholars have utilized neighborhood disorganization theory (Shaw & McKay, 1969) to understand how negative neighborhood conditions can lead to social disorder. More specifically, Harding (2009) argued that violence impacts mental health by increasing stress (Charles, Dinwiddie, & Massey, 2004) and by limiting residents’ access to public spaces (Anderson, 1999; Venkatesh, 2002), which deprives them of opportunities to socialize and build collective efficacy with neighbors. This framework calls for simultaneously examining individual characteristics and neighborhood-level factors that may disadvantage individuals and families (Rankin & Quane, 2000). We consider this a useful framework for considering maternal fear of children playing outdoors, especially given that mothers may be particularly susceptible to altering their behaviors because of fear (Snedker, 2006). We suspect that mothers, who are largely responsible for directing their preschool-aged children’s daily activities and routines, are likely to make decisions about their child’s outdoor play based in part on their perceptions of safety outside the home.

We also draw on theories of social isolation (Rankin & Quane, 2000; Wilson, 1996) which argue that one of the mechanisms through which neighborhood disadvantage negatively impacts residents is via resource-poor neighborhood social networks and more generally limiting the development of social capital (Coleman, 1990). Building on Kim and Ross’ (2009) positioning of social support and psychological well-being as buffers from the strain of the social isolation associated with living in a poor neighborhood, as well as Christie-Mizell and Erickson’s (2007) work demonstrating the importance of maternal perceptions of neighborhoods, we consider three measures of socioemotional health and social support which may moderate the effects of neighborhood poverty on maternal fears: not being depressed, having at least two close friends, and perceiving high levels of neighborhood collective efficacy. In other words, despite the strong influence of neighborhood poverty on fear of crime, positive socioemotional characteristics like not being depressed, social support, and perceiving a high degree of shared trust and norms among neighbors may work to reduce maternal fear.

Exploring Buffers of the Effects of Neighborhood Poverty on Maternal Fears

First, not being depressed may buffer maternal perceptions of fear in poor neighborhoods. Previous scholarship has examined how fear of crime is associated with higher levels of stress and emotional distress (Nasar & Jones, 1997), and depressed adults are more likely to report fear of crime (Stafford, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007), suggesting that mothers with lower levels of depressive symptoms may be less likely to report fear of outdoor play. However, the same negative neighborhood conditions that are associated with fear of crime and neighborhood safety have also been found to influence mothers’ risks for depression (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Ross, 2000), and exposure to violence has been linked to high levels of depression and anxiety among both mothers (Aisenberg, 2001) and children (Wallen & Rubin, 1997). Although neighborhood physical and social factors may combine to influence the mental health of residents (Mair, Diez Roux, & Morenoff, 2010), it is likely that not being depressed may help protect parents from the fear-inducing effects of living in a poor neighborhood. Thus, we hypothesize that not being depressed will buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty on maternal fears of outdoor play.

Mothers’ access to social support may also combat the effects of living in poverty on fears of letting children play outside. Instrumental support, such as the ability to borrow money or depend on someone for emergency child-care, is linked to emotional aid (Levanthal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; McLoyd, 1990; Rankin & Quane, 2000) and not being depressed (Strine, Chapman, Balluz, & Mokdad, 2008). Furthermore, work by Umberson and colleagues (1996) found that compared to men, women were more sensitive to the positive effects of social support and that women lacking supportive relationships were at higher risk for psychological distress, further suggesting that social support may be a particularly important buffer for mothers living in poor neighborhoods. However, some previous scholarship found that the positive effects of instrumental and friend support can be attenuated for mothers living in poverty (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002; Rankin & Quane, 2000), which suggests that social support may be limited in its ability to buffer maternal perceptions of fear of violence. Also, some scholars have posited that, within poor neighborhoods, friends can actually be a negative drain on limited resources (Kawachi & Berkman, 2000; Rankin & Quane, 2000). Other studies have found that social isolation (ie, lack of social support) is negative for maternal well-being in non-poor neighborhoods, but has no effect on mothers in poor neighborhoods (Rajaratnam, O’Campo, Caughy, & Muntaner, 2008). Nevertheless, we hypothesize that having high instrumental support and having two or more close friends will buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty on maternal fears of outdoor play.

Beyond individual mental health and social supports, positive community-level resources may also help to buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty on mothers’ fears of letting their children play outdoors. Maternal perceptions of the level of collective efficacy reflect the level of shared understandings and trust in a neighborhood, and previous scholarship has demonstrated that mothers with stronger social ties to their neighbors report lower levels of fear and mistrust (Ross & Jang, 2000). However, mothers who live in poor, disordered neighborhoods also report fewer neighborhood social ties (Ross & Jang, 2000), and the social characteristics of neighborhoods known to influence fear include general ‘neighborhood disorder,’ or ‘incivilities’ (Kanan & Pruitt, 2002; Wyant, 2008), poverty (Markowitz, Bellair, Liska, & Liu, 2001; Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004; Scarborough et al., 2010), and the proportion of Blacks and Hispanics present in the neighborhood (Grow et al., 2010; Schieman, 2009). These findings suggest that mothers in poor neighborhoods likely face social conditions that may decrease available levels of social support, or do not receive the same benefits of social support (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002). Nevertheless, given the subjective nature of mother’s perceptions of neighborhood disorder, and the importance of accounting for both objective and subjective measures of neighborhoods (Christie-Mizell, Steelman, & Stewart, 2003), mothers in objectively poor neighborhoods may still perceive high levels of community social support, and we hypothesize that high levels of self-reported neighborhood collective efficacy will buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear of outdoor play.

Finally, given that any observed effects on the relationship between neighborhood poverty and fear of outdoor play may be related to other characteristics associated with neighborhood poverty, fear of crime, and our hypothesized buffers, we include a number of control measures. Parent-child characteristics including race, family socioeconomic status (SES), general health status, and mother’s age (e.g. Singh et al., 2010), along with the child’s gender and age (Bacha et al., 2010; Carver et al., 2010) have been shown to be significantly associated with children’s activity levels and are also often associated with fear of crime in general (Kanan & Pruitt, 2002; Kruger, Hutchison, Monroe, Reischl, & Morrel-Samuels, 2007), making it important to control for their effects. Additionally, we control for whether or not mothers report being in a stable relationship or having a grandmother living in their home, as this may influence her levels of stress and perceived social support (Black & Nitz, 1996; Ross, 1995; Waite & Gallagher, 2000; Williams, Sassler, & Nicholson, 2008). We also include a measure of residential mobility given our expectation that mobility might be associated with disorder or fear (Sampson & Raudenbush, 2004), and a crude measure of household crowding, the number of residents, which is associated with physical activity for adolescents (Babey, Hastert, & Brown, 2007). We control for whether the family lives in public housing, given the association between public housing and children’s outdoor play (Kimbro et al., 2011). Finally, we also control for city-level crime rates and whether the mother reports ever experiencing domestic violence, given its connections to fear of crime as well as poor mental health (e.g. Coker et al., 2002).

Method

Data

The Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study (FFCWS) follows a birth cohort of urban parents and their children (Baseline N = 4,898) from 20 U.S. cities, and when weighted it is representative of all births in large U.S. cities in 1998-99. The study oversampled unmarried mothers, who make up about three quarters of the sample, with the remaining one quarter of mothers married at the time of the child’s birth. Follow-up interviews were conducted when the child was one (1999-2000), three (2001-2002), and five years old (2003-2004). Data for this paper are from the 3,448 mothers and children who completed all five waves of the core study, and who were still living in the same city when the child was five years old. U.S. Census 2000 data for Census tracts were merged with the FFCWS data file. For further information about the Fragile Families Study, please visit http://crcw.princeton.edu/ff.asp. These data are ideal for our research questions because they are, as far as we know, the only longitudinal data from multiple large U.S. cities on young children which incorporate both mother-reported and objectively-measured neighborhood characteristics. In addition, the data are racially diverse and include a large proportion of low SES families, so a wide range of neighborhood conditions and experiences are represented.

Measures

Our outcome of interest is a dichotomous measure based on the question, “Have you ever been afraid to let [the focal child] go outside due to violence?” (1 = fearful). We are not able to distinguish whether a mother is responding to the question as though the child would be playing outside alone relative to playing outside with adult supervision. This measure is taken from the five-year survey.

Maternal and Child Background Characteristics

With the exception of measures which reflect change from the three-year to five-year survey, almost all covariates are measured at the three-year wave (see below for exceptions) in order to more carefully clarify the causal order of which factors influence maternal fear, but it is important to note that we are not assessing change with our analysis. The data provide a variety of background factors likely to be related to maternal fear and children’s outdoor play. We classified children into racial/ethnic categories: Non-Hispanic White (reference), Non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic/Other (only about 100 respondents were of “Other” race), and controlled for the child’s age in months, child’s gender (1 = male), whether the mother reported the child to be in fair or poor health, and whether she reported herself to be in fair or poor health. We controlled for mothers’ educational attainment (when the child was born) with a set of indicators for ‘did not complete high school’ (reference group), ‘completed high school,’ and ‘some college or more,’ mother’s age, and the mother’s cognitive ability from the Similarities subset of the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised (WAIS-R) (Wechsler, 1981). We included measures for mother’s employment, with ‘not employed outside the home’ as the reference category, compared to ‘full-time’ and ‘part-time’ work. We also included a continuous measure of the income-to-needs ratio for the household, and an indicator for whether the family received TANF in the last year. The family structure indicators are based on both the three- and five-year surveys, and report the mother’s current relationship with a partner (which could be the child’s biological or social father) – married, cohabiting, or single; as well as her relationship instability – entering or exiting a romantic relationship over the past two years, because relationship instability may influence mental health and fear (Brown, 2000). Thus, we compare mothers in a stable marital relationship to those who were ‘stable cohabiters,’ ‘stable singles,’ ‘entered a relationship’ or ‘exited a relationship.’ As an additional measure of family structure, we include an indicator for whether the mother’s mother (the child’s grandmother) lives in the household (1 = grandmother in household).

Maternal Mental Health and Social Support

Because we believe that fear may be related to mothers’ mental health, we also included an indicator for whether the mother is not clinically depressed, an indicator based on the CIDI-SF (Kessler et al., 1998). In addition, we include a parenting stress index score – comprised of four questions which ask mothers about the extent of their agreement with statements about the difficulties of parenting. To create the index, we summed responses to the scale, with higher values representing higher parenting stress (α = .79). Finally, we include an indicator for whether the mother has ever reported (throughout the waves of the study) experiencing intimate partner violence. As rough measures of the degree of social support a mother experiences, we include indicators for whether the mother has one or fewer close friends; and whether a mother has high instrumental support (the ability to borrow money, depend on someone for emergency child-care, and provide a place to live if necessary – a dichotomous measure for “high support” if she replied yes to all three). We also include measures for (a) whether the family lived in public housing, (b) the number of residents in the household, and (c) whether the family moved between the three-year and five-year surveys.

Neighborhood Measures

To measure neighborhood context, we incorporate data from the 2000 Census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001) and include a measure of the proportion of households living below poverty to control for tract-level differences in neighborhood poverty, as well as a measure of the proportion of the population in the Census tract who were African American. Both of these measures are continuous and were standardized in the models. The Census tract is the smallest residential area we have in our data, although we recognize that Census block data might have been preferable. Correlations for Census tract and block measures, however, are generally very high (Diez-Roux et al., 2001), and we also presume that the influence of contextual poverty on maternal fear and children’s outdoor play may extend beyond the immediate environment of the home. Very few tracts represented in the sample have more than two respondents who reside there (just 10%). Thus, the poverty and racial composition measures are broad representations of the neighborhood and are not utilized in a multilevel framework.

To measure neighborhood collective efficacy, we used a slightly modified version of the neighborhood social environment measures in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) Community Survey Questionnaire (Earls, Brooks-Gunn, Raudenbush, & Sampson, 2002). Ten items assessing the mother’s perception of neighborhood cohesion were summed to create the scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). There were two types of questions. The first five questions gauged how likely the mother thought that neighbors would intervene in certain situations, such as “If children were skipping school and hanging out on the street.” Mothers chose one of four responses; from “very likely” to “very unlikely.” The second five questions asked about how cohesive mothers felt their neighborhoods were, such as, “People around here are willing to help their neighbors.” Mothers chose one of four responses, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The collective efficacy score was created by averaging a mother’s responses to all ten questions, and then dividing the measure into tertiles, for ‘low collective efficacy’ (the reference group), ‘medium collective efficacy,’ and ‘high collective efficacy.’ The two subsets of questions were correlated at .49, but given the relatively high Cronbach’s alpha score and the desire to follow the example of Earls et al. (2002), we combine the two types of questions into one scale. Unfortunately, this measure of collective efficacy is only available at the five-year survey, so we are unable to account for her perceptions of collective efficacy at the three-year wave. Finally, we include a measure of a three-year average (2002-2004) of the violent crime rate for each city. Ideally, we would have crime rate data at the zip code level or below, but this data is not available for every city. This information is from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports for each of the twenty cities.

Missing data for the covariates is generally low; with the exception of 155 mothers who were missing Census tract information necessary to link those families with data on neighborhood poverty and racial composition. All missing data were imputed using multiple imputation techniques, and the imputed data was used for the regression analyses (results using non-imputed data were substantively similar).

Analytic Strategy

First, we present descriptive statistics and bivariate tests for significant differences between mothers living in low- and high-poverty neighborhoods. Chi-square tests were utilized for dichotomous measures, and two-tailed t-tests were used for continuous measures. As our ‘maternal fear’ outcome measure is dichotomous, we utilize logistic regression models to test our hypotheses. We use stepwise models in two phases of the analysis – first, to assess the independent associations between our covariates of interest and our outcome; and second, we incorporate interaction terms to test our hypotheses about social support, collective efficacy, and not being depressed as potential buffers of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear. All models (except those testing the influence of city-level crime rates) include city fixed-effects and standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the city level.

Results

Table 1 presents means or proportions for each variable as well as results of bivariate tests comparing the difference in means between respondents who live in low (at or below the mean) and high (above the mean) poverty neighborhoods. On average, mothers living in high poverty neighborhoods are in areas with 31% of households under the federal poverty line; while those living in low poverty areas live in neighborhoods where 8% of households are below the poverty line. In the full sample, 16% of mothers report being fearful of their child playing outside because of violence, but more than twice as many mothers living in high poverty neighborhoods compared to low poverty neighborhoods report being fearful (24% compared to 10%). Note the relatively disadvantaged nature of the FFCWS sample – just 36% of mothers reported some college or more; 19% report receiving TANF, and just 27% of the sample are in stable, married relationships. Approximately half of all respondents moved at least once in the past two years.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, FFCWS Sample, by Neighborhood Poverty

| Full sample | High Poverty Neighborhood |

Low Poverty Neighborhood |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Mother is fearful of her child playing outdoors | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.10*** |

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Race (Ref: White) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.32*** |

| Black | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.39*** |

| Hispanic | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Child is male | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.51 |

| Child’s Age (months) | 61.7 (2.8) | 61.8 (2.8) | 61.7 (2.8) |

| Child has fair/poor health | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01*** |

| Mom has fair/poor health | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.11*** |

| Mother’s Age (years) | 30.2 (6.1) | 29.3 (5.7) | 31.0 (6.2)*** |

| Socioeconomic Status | |||

| Household Inc/Poverty Threshold | 1.87 (1.91) | 2.4 (2.2) | 1.2 (1.3)*** |

| Household receives TANF | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.12*** |

| Mother’s Education (ref: Less than HS) | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.25*** |

| HS | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.30* |

| College | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.45*** |

| Mother’s Cog. Ability | 6.8 (2.6) | 6.4 (2.6) | 7.1 (2.7)*** |

| Mother’s Employment Status (ref: Not working) | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.38*** |

| Full-time | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.38** |

| Part-time | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.24** |

| Family Support | |||

| Grandmother Present in household | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Mother’s relationship status (Ref: Stable marital relationship) |

0.27 | 0.16 | 0.37*** |

| Single (stable) | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.28*** |

| Entering a relationship | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Exiting a relationship | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.19*** |

| Cohabiting (stable) | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10** |

| Household Characteristics | |||

| More than four residents | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.44** |

| Family lives in public housing | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.08*** |

| Moved between three and five year surveys | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.45** |

| Maternal Mental Health and Domestic Violence | |||

| Mother not depressed at three-year survey | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.81 |

| Mother’s stress index score at three-year survey | 8.9 (2.7) | 9.1 (2.8) | 8.9 (2.6)* |

| Ever experienced domestic violence | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Social Support | |||

| Mother has 0 or 1 close friends | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.15*** |

| Mother has high instrumental support | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.82*** |

|

Neighborhood Collective Efficacy (ref: High

CE) |

|||

| High collective efficacy | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.39*** |

| Medium collective efficacy | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| Low collective efficacy | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.30*** |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||

| % households in poverty (variable standardized for models) |

0.18 | 0.31 | 0.08*** |

| % Black (variable standardized for models) | 0.40 | 0.58 | 0.26*** |

| City-Level Violent Crime Rate (variable standardized for models) |

1012.6 (393.5) | 1070.4 (386.5) | 963.0 (392.8)*** |

|

| |||

| N | 3,448 | 1,579 | 1,869 |

NOTE: Chi-squares or t-tests comparing families living in low-poverty to high-poverty neighborhoods. Descriptives based on non-imputed data.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed test).

Table 2 presents results from logistic regression models predicting maternal fear, in the form of odds ratios. In Model 1, which includes all of our control measures, we first notice large racial/ethnic differences in the odds of a mother being fearful of her child playing outdoors – Black mothers have 2.29 times the odds, and Hispanic mothers have 2.01 times the odds, compared to white mothers, of being fearful, adjusting for a variety of child and mother background factors. We also see that a mother has higher odds of being fearful if she reports herself as being in fair or poor health, if she receives TANF, if she lives in public housing, and if she has fewer than two close friends. We see that the odds of being fearful decrease as the income-to-poverty ratio increases; if a mother has at least a high school degree; if she works full-time, if she is not depressed, and if she reports high instrumental social support.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios, Predicting Maternal Fear

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Race (Ref: White) | |||||

| Black | 2.29** | 2.03** | 1.55 | 1.38 | 1.57 |

| Hispanic | 2.01* | 1.74* | 1.67† | 1.46 | 1.64** |

| Child is male | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.87† | 0.89 | 0.85† |

| Child’s Age (months) | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.02 |

| Child has fair/poor health | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.95 |

| Mom has fair/poor health | 1.27* | 1.17 | 1.28* | 1.21† | 1.20† |

| Mother’s Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Socioeconomic Status | |||||

| Household Inc/Poverty Threshold | 0.88** | 0.93† | 0.91* | 0.96 | 0.97† |

| Household receives TANF | 1.32* | 1.31* | 1.28* | 1.27* | 1.31* |

| Mother’s Education | |||||

| HS | 0.79† | 0.78* | 0.78 | 0.78† | 0.82 |

| College | 0.76* | 0.72** | 0.80* | 0.77* | 0.84 |

| Mother’s Cog. Ability | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Mother’s Employment Status | |||||

| Full-time | 0.74* | 0.73* | 0.75* | 0.73* | 0.69** |

| Part-time | 0.80† | 0.80† | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| Family Support | |||||

| Grandmother Present in household | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.95 |

| Mother’s relationship status (Ref: Stable marital relationship) |

|||||

| Single (stable) | 1.23 | 1.30† | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.13 |

| Entering a relationship | 1.54† | 1.59* | 1.52† | 1.60* | 1.73** |

| Exiting a relationship | 1.33 | 1.37† | 1.26 | 1.31 | 1.32 |

| In a stable cohabitating relationship | 1.24 | 1.30† | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.24 |

| Household Characteristics | |||||

| More than four residents | 1.21* | 1.27* | 1.19† | 1.25* | 1.17† |

| Family lives in public housing | 1.53*** | 1.45** | 1.38* | 1.31* | 1.28* |

| Moved between three and five year surveys | 0.88 | 0.86* | 0.88 | 0.87* | 0.80** |

| Maternal Mental Health and Domestic Violence | |||||

| Mother not depressed at three-year survey | 0.71** | 0.73* | 0.70** | 0.72* | 0.76* |

| Mother’s stress index score at three-year survey | 1.04* | 1.02 | 1.05* | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Ever experienced domestic violence | 1.40 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 1.29 | 1.23 |

| Social Support | |||||

| Mother has 0 or 1 close friends | 1.45** | 1.25† | 1.48** | 1.27† | 1.23 |

| Mother has high instrumental support | 0.75*** | 0.86 | 0.75*** | 0.86 | 0.83† |

| Neighborhood Collective Efficacy (ref: Low CE) | |||||

| Medium collective efficacy | 0.34*** | 0.35*** | 0.34*** | ||

| High collective efficacy | 0.13*** | 0.13*** | 0.12*** | ||

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||

| % households in poverty (standardized) | 1.29*** | 1.28*** | 1.33*** | ||

| % Black (standardized) | 1.23* | 1.23* | 1.25* | ||

| City-Level Violent Crime Rate (standardized) | 1.02 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Sample Size | 3448 | 3448 | 3448 | 3448 | 3448 |

NOTE: Models 1-4 include city fixed-effects and standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the city level.

Model 5 does not include city fixed-effects, as it tests the association between city-level crime rates and fear.

p≤.10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

In Model 2, we add the mothers’ perceptions of neighborhood collective efficacy to the model, and see that mothers living in neighborhoods with medium or high collective efficacy have much lower odds of fear relative to mothers who report low collective efficacy. Model 3 tests the association between the neighborhood demographic measures and maternal fear, and we see that living in higher-poverty neighborhoods as well as those with a larger proportion of African American residents increase the odds that a mother reports being fearful of her child playing outdoors. In model 4, we include both the subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics measures to test whether the influence of either changes, and the results already described remain relatively unchanged. Finally, in Model 5 we add the city-level violent crime rate to the full model, to test whether our observed associations differ when we account for an objective measure of crime. In this final model, which does not include city fixed-effects because we are testing a city-level measure, we see that contrary to expectations, city-level violent crime is not associated with maternal fear. Thus, we do not include this measure in our subsequent models.

Table 3 presents results of our models which test whether collective efficacy, maternal mental health, or social support buffer the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear. Here, we include interaction terms between neighborhood poverty and our potential buffering measures to see whether the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear is reduced under certain circumstances. In model 1, we test whether the influence of neighborhood poverty on fear is reduced (or buffered) if mothers report medium or high collective efficacy neighborhoods. We see that an increase in poverty influences maternal fear in a similar way for mothers living in low and medium collective efficacy neighborhoods. But for mothers who report high collective efficacy, the effect of increasing poverty is actually larger – contrary to our hypothesis that higher collective efficacy would buffer the influence of poverty. In other words, living in a high-collective efficacy neighborhood slightly exacerbates the influence of poverty on maternal fear. Despite this slight increase to the influence of poverty on fear, however, mothers living in high collective efficacy neighborhoods (and medium collective efficacy neighborhoods) still have lower probabilities of fear across levels of neighborhood poverty.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios, Predicting Maternal Fear

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Race (Ref: White) | ||||

| Black | 1.37 | 1.36 | 1.35 | 1.38 |

| Hispanic | 1.45 | 1.41 | 1.44 | 1.46 |

| Child is male | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Child’s Age (months) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Child has fair/poor health | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| Mom has fair/poor health | 1.20† | 1.21† | 1.22† | 1.21† |

| Mother’s Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Household Inc/Poverty Threshold | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Household receives TANF | 1.27* | 1.27* | 1.27* | 1.27* |

| Mother’s Education | ||||

| HS | 0.77† | 0.78† | 0.78† | 0.78† |

| College | 0.76* | 0.76* | 0.77* | 0.77* |

| Mother’s Cog. Ability | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Mother’s Employment Status | ||||

| Full-time | 0.73* | 0.74* | 0.73* | 0.73* |

| Part-time | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81† | 0.81 |

| Family Support | X | X | X | X |

| Household Characteristics | X | X | X | X |

| Maternal Mental Health and Domestic Violence | ||||

| Mother not depressed at three-year survey | 0.72** | 0.81 | 0.72** | 0.72* |

| Mother’s stress index score at three-year survey | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Ever experienced domestic violence | 1.31 | 1.27 | 1.28 | 1.29 |

| Social Support | ||||

| Mother has 0 or 1 close friends | 1.27† | 1.27† | 1.39* | 1.27† |

| Mother has high instrumental support | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Neighborhood Collective Efficacy (ref: Low CE) | ||||

| Medium collective efficacy | 0.33*** | 0.34*** | 0.35*** | 0.35*** |

| High collective efficacy | 0.11*** | 0.13*** | 0.13*** | 0.13*** |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||

| % households in poverty (standardized) | 1.19** | 1.61*** | 1.35*** | 1.28* |

| % Black (standardized) | 1.23* | 1.23* | 1.23* | 1.23* |

| Interactions between poverty and potential buffers | ||||

| Medium collective efficacy * % households in poverty |

1.11 | |||

| High collective efficacy * % households in poverty | 1.30* | |||

| Mother not depressed * % households in poverty | 0.74** | |||

| Mother has few close friends * % households in poverty |

0.81† | |||

| Mother has high support * % households in poverty | 0.99 | |||

|

| ||||

| Sample Size | 3448 | 3448 | 3448 | 3448 |

NOTE: All models include all control measures presented in Table 2. All models include city fixed-effects and standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the city level.

p≤.10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

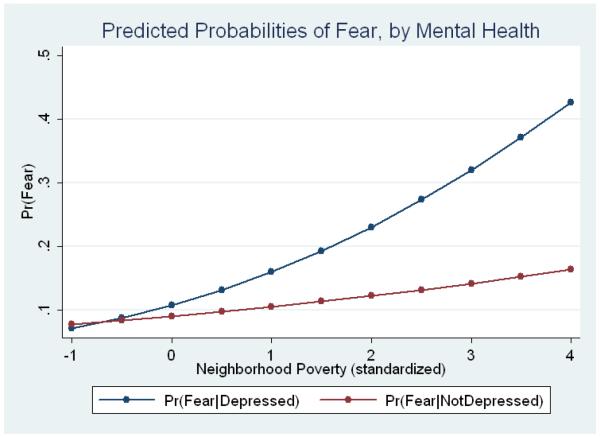

Model 2 and Figure 1 present results of testing our hypothesis that not being depressed would buffer the influence of neighborhood poverty on fear for mothers, and we find some evidence supporting our contention (though note that the main effect of not being depressed becomes insignificant). Mothers who are not depressed experience little growth in the predicted probability of fear as neighborhood poverty increases; compared to mothers who are depressed. In other words, not being depressed buffers the influence of poverty on maternal fear. This effect, however, does not become pronounced until after neighborhood poverty surpasses the mean, and grows as neighborhood poverty increases. Models 3 and 4 test whether social support buffers the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear; and we do not find evidence for our hypothesis about the buffering influence of social support.

Figure 1.

Discussion

This paper demonstrates the potential utility for researchers interested in the healthy development of children of focusing on maternal fear regarding children’s outdoor play. Studies of U.S. children’s time use have demonstrated large drops in the percentage of time spent in free play (Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001), and Burdette and Whitaker (2005a) have argued that we need to “resurrect” children’s play. Our paper conceptualizes a mother’s fear of her five-year-old child playing outside as a major component of her decisions regarding the child’s free play time. Thus, we test maternal, household, and neighborhood characteristics which may be related to maternal fear. We find individual characteristics such as the household’s economic status, the mother’s education and employment, and her physical and mental health status, to influence fear. We also find that a mother’s perception of her neighborhood’s collective efficacy is associated with fear, such that mothers who believe they are in medium or high collective efficacy neighborhoods are less likely to be fearful of their child playing outdoors. In addition, we find that the percent of households in poverty and the percent of Blacks in the neighborhood are associated with increased maternal fear, after controlling for a robust set of control measures. The persistent influence of neighborhood demographic characteristics on maternal fear is in line with prior research demonstrating the powerful influence of neighborhood racial/ethnic composition on fear (Kanan & Pruitt, 2002; Schieman, 2009) and children’s healthy development (Grow et al., 2010).

Importantly, we also find some evidence that not being depressed buffers the influence of neighborhood poverty on maternal fear. Given the elevated rates of depression found in previous studies of mothers in poor neighborhoods (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Mair et al., 2010; Ross, 2000), our results suggest that efforts to minimize depression among mothers living in poverty could have significant, positive impacts on parenting behaviors, and particularly in the promotion of children’s outdoor play. Our hypotheses received mixed support, however, as social support did not buffer the influence of neighborhood poverty on fear; and higher collective efficacy actually exacerbated the influence of neighborhood poverty on fear. We speculate that in the poorest neighborhoods, mothers may be perceiving high levels of neighborhood collective efficacy because there has been a real (or perceived) threat to the members of the community (Janowitz, 1967; Rankin & Quane, 2000; Suttles, 1972), and that parents may be mobilizing to manage the risks for their children (Furstenberg, 1993), while at the same time reporting high levels of fear because of this real or perceived threat. In other words, in high poverty neighborhoods, high collective efficacy may be an indicator of a real or perceived neighborhood threat, which would explain why the likelihood of reporting fear of outdoor play increases for these mothers.

Implications for Practice and Limitations

Our findings, which suggest the crucial role of maternal perceptions of neighborhoods, have implications for policies and practitioners seeking to improve young children’s outdoor play. First, although high collective efficacy appears to intensify the effects of neighborhood poverty on maternal fears, mothers reporting higher levels of collective efficacy have lower absolute levels of fear, regardless of the level of poverty in their neighborhoods. The strong associations among neighborhood collective efficacy and fear of outdoor play suggest that interventions ought to target community building as a key mechanism for decreasing maternal fear. Second, higher levels of neighborhood poverty, as well as the percent of Black residents in the neighborhood, are consistently associated with higher likelihoods of fear, and our findings suggest that interventions ought to be directed at these neighborhoods.

There are, however, some limitations to our study. First, we were unable to distinguish whether mothers were envisioning sending a child out alone or with supervision when they answered whether or not they were fearful. It is plausible that maternal fear may operate differently depending on whether respondents were imagining their child playing outside alone or under adult or sibling supervision, and it is likely that this relationship differs for older versus younger children. Second, we only had access to city-level crime data, and much of the fear of crime literature suggests that neighborhood-level measures are more important predictors of fear. In addition, although the study is longitudinal, we are unable to take advantage of the longitudinal data as we only have the outcome measure at the five-year follow-up. Thus, we are unable to sufficiently address issues of time ordering in our analysis. Finally, because of the sampling design, we did not have enough respondents in each neighborhood to allow for multilevel analyses which would allow us to more precisely estimate the influence of neighborhood poverty. In addition, we are unable to account for the possibility of mothers selecting into neighborhoods based on key characteristics in our study. Nevertheless, we believe our findings represent a significant contribution to the child health literature by exploring maternal fear, as well as providing an assessment of maternal fear in urban areas for practitioners and policymakers interested in increasing children’s outdoor play.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this article was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through its national program Active Living Research (ALR). The authors thank the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through grants R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations for their support of the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study. The authors appreciate feedback from Justin T. Denney, Christopher Browning, and Bridget Gorman.

Contributor Information

Rachel Tolbert Kimbro, Department of Sociology, MS-28 Rice University 6100 Main St. Houston, TX 77005 (713) 348-4265 (office) (713) 348-5296 (fax) rtkimbro@rice.edu.

Ariela Schachter, Department of Sociology Stanford University 450 Serra Mall Stanford, CA 94305-2047 (908) 723-3027 arielas1@stanford.edu.

References

- Aisenberg E. The effects of exposure to community violence upon Latina mothers and preschool children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23(4):378. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. WW Norton & Company; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Babey SH, Hastert TA, Brown RE. UCLA Health Policy Research Brief. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2007. Teens Living in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Lack Access to Parks and Get Less Physical Activity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacha J, Appugliese D, Coleman S, Kaciroti N, Bradley R, Corwyn R, Lumeng J. Maternal perception of neighborhood safety as a predictor of child weight status: the moderating effect of gender and assessment of potential mediators. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2010;5:72–79. doi: 10.3109/17477160903055911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Nitz K. Grandmother co-residence, parenting, and child development among low income, urban teen mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;18:218–226. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00168-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky A. Resilient single mothers in risky neighborhoods: Negative psychological sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(4):347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. The effect of union type on psychological well-being: depresion among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette H, Whitaker R. Resurrecting Free Play in Young Children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005a;159(1):46–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette H, Whitaker R. A National Study of Neighborhood Safety, Outdoor Play, Television Viewing, and Obesity in Preschool Children. Pediatrics. 2005b;16(3):657–662. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L, Graham J. Neighborhood rhythms and the social activities of adolescent mothers. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1998;82:7–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho I, Lewis D. Beyond community: Reactions to crime and disorder among inner-city residents. Criminology. 2003;41:779. [Google Scholar]

- Carver A, Timperio A, Crawford D. Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children’s physical activity—a review. Health and Place. 2008;14(2):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver A, Timperio A, Hesketh K, Crawford D. Are children and adolescents less active if parents restrict their physical activity and active transport due to perceived risk? Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:1799–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1310–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Dinwiddie G, Massey D. The Continuing Consequences of Segregation: Family Stress and College Academic Performance. Social Science Quarterly. 2004;85(5):1353–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Christie-Mizell CA, Steelman LC, Stewart J. Seeing Their Surroundings: The Effects of Neighborhood Setting and Race on Maternal Distress. Social Science Research. 2003;32(3):402–428. [Google Scholar]

- Christie-Mizell CA, Erickson R. Mothers and Mastery: The Consequences of Perceived Neighborhood Disorder. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70(4):340–365. [Google Scholar]

- Clements R. An investigation of the State of Outdoor Play. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 2004;5:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Coker A, Davis K, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt H, Smith P. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cradock AL, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Gortmaker SL, Buka SL. Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Youth Participation in Physical Activity in Chicago. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006;3(19) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux AV, Kiefe CI, Jacobs DR, Jr., Haan M, Jackson SA, Nieto FJ, Paton CC, Schulz R. Area characteristics and individual-level socioeconomic position indicators in three population-based epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2001;11(6):395–405. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls FJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) Harvard Medical School; Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; Boston, MA: Ann Arbor, MI: 2002. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L, Eliottt M, Cuccaro P, Schuster M, Gilliland J, Grunbaum J, Franklin F, Tortolero S. Influences of physical and social neighborhood environments on children’s physical activity and obesity. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:271–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg F, Wilson WJ. Sociology and the public agenda. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods; pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Chang Y, Krull JL. Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg KR. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):182–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow HMG, Cook AJ, Arterburn DE, Saelens BE, Drewnowski A, Lozano P. Child obesity associated with social disadvantage of children’s neighborhoods. Social Science & Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.018. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding D. Collateral Consequences of Violence in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2009;88(2):757–784. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Sandberg JF. How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(2):295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Janowitz M. The community press in an urban setting. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RL. Neighborhood Transformation and Family Development Initiative. Annie E. Casey Foundation; Baltimore, MD: 1998. Indicators of family strengths and resilience that influence positive child-youth out-comes in urban neighborhoods: A review of quantitative and ethnographic studies. [Google Scholar]

- Kanan JW, Pruitt MW. Modeling fear of crime and perceived victimization risk: The (in)significance of neighborhood integration. Sociological Inquiry. 2002;72(4):527–548. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LE. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman LE, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun TB, Wittchen HU. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Ross CE. Neighborhood-specific and general social support: which buffers the effect of neighborhood disorder on depression? Jounral of Community Psychology. 2009;37(6):725–736. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbro RT, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S. Young Children in Urban Areas: Links Among Neighborhood Characteristics, Weight Status, Outdoor Play, and Television-Watching. Social Science and Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.015. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger DJ, Hutchison P, Monroe MG, Reischl T, Morrel-Samuels S. Assault injury rates, social capital, and fear of neighborhood crime. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(4):483–498. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liska A, Baccaglini W. Feeling safe by comparison: crime in the newspapers. Social Problems. 1990;37(3):360–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Appugliese D, Cabral HJ, Bradley RH, Zuckerman B. Neighborhood Safety and Overweight Status in Children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(1):25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair C, Roux A.V. Diez, Morenoff J. Neighborhood stressors and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the Chicago Community Adult Study. Health & Place. 2010;16:811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE, Bellair PE, Liska AE, Liu J. Extending social disorganization theory: Modeling the relationships between cohesion, disorder and fear. Criminology. 2001;39:293–321. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasar JL, Jones KM. Landscapes of fear and stress. Environment and Behavior. 1997;29(3):291–323. [Google Scholar]

- Papas M, Alberg A, Ewing R, Helzlsouer K, Gary T, Klassen A. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiological Review. 2007;29(1):129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntenney D. The impact of gang violence on the decisions of everyday life: Disjunctions between policy assumptions and community conditions. Journal of Urban Affairs. 1997;19:143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin BH, Quane JM. Neighborhood poverty and the social isolation of inner-city African American families. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):139–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam JK, O’Campo P, Caughy MO, Muntaner C. The effect of social isolation on depressive symptoms varies by neighborhood characteristics: a study of an urban sample of women with pre-school aged children. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2008;6(4):464–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Richards R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;7(08):1081–1088. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE. Reconceptualizing marital status as a continuum of social attachment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57(1):129–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Jang SJ. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:401–420. doi: 10.1023/a:1005137713332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. The role of built environments in physical activity, eating, and obesity in childhood. The Future of Children. 2006:89–108. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(4):319–42. [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough BK, Like-Haislip TZ, Novak KJ, Lucas WL, Alarid LF. Assessing the relationship between individual characteristics, neighborhood context, and fear of crime. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2010;38:819–826. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Huebner B, Bynum T. Fear of crime and criminal victimization: Gender-based contrasts. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S. Residential Stability, Neighborhood Racial Composition, and the subjective assessment of neighborhood problems among older adults. The Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50:608–632. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CR, McKay HD. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Siahpush M, Kogan M. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, built environments, and childhood obesity. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):503–512. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedker K. Altruistic and Vicarious Fear of Crime: Fear for Others and Gendered Social Roles. Sociological Forum. 2006;21(2):163–195. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M, Chandola T, Marmot M. Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(11):2076–2081. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz L, Mokdad AH. Health-related qualit of life and health behaviors by social and emotional support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttles GD. The social construction of communities. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Timperio A, Salmon J, Telford A, Crawford D. Perceptions of local neighbourhood environments and their relationship to childhood overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29:170–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Chen MD, House JS, Hopkins K, Slaten E. The effect of social relationships on psychological well-being: are men and women really so different? American Sociological Review. 1996;61(5):837–857. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Census 2000 Summary Files 1 and 3. United States: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S. American project: The rise and fall of an American ghetto. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wallen J, Rubin R. The role of the family in mediating the effects of community violence on children. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2(1):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The case for marriage. Doubleday; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Warr M, Ellison C. Rethinking social reactions to crime: Personal and altruistic fear in family households. American Journal of Sociology. 2000;106(3):551–578. [Google Scholar]

- Warr M, Stafford M. Fear of victimization: a look at proximate causes. Social Forces. 1982;61:1033–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS-R Manual) The Psychological Corporation. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Weir LA, Etelson D, Brand DA. Parents′ perceptions of neighborhood safety and children′s physical activity. Preventive Medicine. 2006;43(3):212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Sassler S, Nicholson L. For better or for worse? The consequences of marriage and cohabitation for single mothers. Social Forces. 2008;86(4) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears: the world of the new urban poor. Alfred A. Knopf; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wyant B. Multi-level impacts of perceived incivilities and perceptions of crime risk on fear of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2008;45:39–64. [Google Scholar]