Abstract

MAP kinase (MAPK) cascades are composed of a MAPK, MAPK kinase (MAPKK), and a MAPKK kinase (MAPKKK). Despite the existence of numerous components and ample opportunities for crosstalk, most MAPKs are specifically and distinctly activated. We investigated the basis for specific activation of the JNK subgroup of MAPKs. The specificity of JNK activation is determined by the MAPKK JNKK1, which interacts with the MAPKKK MEKK1 and JNK through its amino-terminal extension. Inactive JNKK1 mutants can disrupt JNK activation by MEKK1 or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in intact cells only if they contain an intact amino-terminal extension. Mutations in this region interfere with the ability of JNKK1 to respond to TNF but do not affect its activation by physical stressors. As JNK and MEKK1 compete for binding to JNKK1 and activation of JNKK1 prevents its binding to MEKK1, activation of this module is likely to occur through sequential MEKK1:JNKK1 and JNKK1:JNK interactions. These results underscore a role for the amino-terminal extension of MAPKKs in determination of response specificity.

Keywords: JNKK1, MEKK1, MAP kinase, interaction, specificity

MAP kinase (MAPK) cascades transduce extracellular cues to the transcriptional machinery, thereby regulating gene expression, cellular homeostasis, and differentiation (Cobb and Goldsmith 1995; Herskowitz 1995; Marshall 1995). MAPK cascades or modules are composed of a MAPK, a MAPK kinase (MAPKK or MEK), and a MAPKK kinase or MEK kinase (MAPKKK or MEKK). The MAPKs mediate effector functions through phosphorylation of substrates involved in cellular regulation (Hill and Triesman 1995; Karin and Hunter 1995). The MAPKKKs, on the other hand, receive regulatory inputs from cell-surface receptors. The identification of multiple MAPKs, MAPKKs, and MAPKKKs, even in unicellular eukaryotes, such as budding yeast, and the ability of these kinases to phosphorylate and activate more than one target when tested in vitro, pose a difficult question regarding the mechanisms that confer biological specificity to MAPK signaling cascades. Despite the potential for extensive cross talk, it is generally observed that individual MAPKs are activated in response to distinct sets of stimuli. Genetic analysis in yeast suggests at least two different solutions to the specificity problem. The prototypical pheromone-responsive MAPK cascade is organized as a distinct signaling module composed of the MAPKs Fus3 and Kss1, the MAPKK Ste7, and the MAPKKK Ste11 (Herskowitz 1995). This module is organized by the scaffolding protein Ste5, which is believed to interact simultaneously with all three components (Choi et al. 1994; Marcus et al. 1994; Printen and Sprague 1994), as well as with upstream regulators (Whiteway et al. 1995). In addition, Ste5 acts as an insulator, preventing cross talk between the pheromone responsive module and other MAPK modules (Yashar et al. 1995). Direct interactions between STE7 and its targets Fus3 and Kss1, however, which are independent of Ste5, were also detected (Choi et al. 1994; Marcus et al. 1994; Printen and Sprague 1994; Bardwell et al. 1996). Ste11 and Ste7 also regulate the invasive growth response, which is activated by starvation (Roberts and Fink 1994) and involves Kss1 but not Fus3, which acts as the output kinase of the pheromone-responsive module (Madhani et al. 1997). It was postulated that the invasive growth MAPK module is organized by another yet-to-be-identified scaffolding protein analogous to Ste5 (Herskowitz 1995). Another MAPK cascade of yeast composed of MAPK Hog1, MAPKK Pbs2, and MAPKKKs Ssk2 and Ssk22, mediates osmoadaptation following activation of the osmosensor Sln1 (Brewster et al. 1993; Maeda et al. 1995). Sho1, a second osmosensor with different properties from Sln1, also regulates Pbs2 and Hog1 (Maeda et al. 1995), but in this case the signal is transmitted through the MAPKKK Ste11 (Posas and Saito 1997). Therefore, Ste11 is involved in three distinct MAPK modules activated by pheromones, starvation, or osmotic stress, yet normally each of the MAPKs that it regulates is potently activated only by one specific stimulus (Madhani et al. 1997; Posas and Saito 1997). Specificity could be maintained through three separate pools of Ste11, but this remains to be demonstrated. It was proposed that specificity in the Sho1 osmoresponsive MAPK module is maintained through physical interactions between Pbs2, Hog1, and Ste11 (Posas and Saito 1997). Pbs2 also interacts with Sho1 (Posas and Saito 1997), but it remains to be determined whether Pbs2 interacts with all of these proteins simultaneously.

By comparison, much less is known about the mechanisms that confer specificity to MAPK modules in mammalian cells. The first mammalian MAPK module defined is composed of the MAPKKK Raf-1 (c-Raf), the MAPKKs MEK1/MEK2, and the MAPKs ERK1/ERK2 (Dent et al. 1992; Cobb and Goldsmith 1995; Marshall 1995). A-Raf and B-Raf also function as MAPKKKs capable of MEK and ERK activation (Marais et al. 1997), although B-Raf is differentially regulated from c-Raf (Vossler et al. 1997). The first identified mammalian homolog of Ste11 was MEKK1 (Lange-Carter et al. 1993). Recently, many related MAPKKKs, including MEKK2, MEKK3, MEKK4, MEKK5, ASK, TAK, and MLK were identified (Yamaguchi et al. 1995; Blank et al. 1996; Tibbles et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996; Gerwins et al. 1997; Ichijo et al. 1997). Initially, MEKK1 was proposed to be an activator of MEK1/MEK2 (Lange-Carter et al. 1993). MEKK1, however, was found to activate additional MAPKKs, including Jun amino (N)-terminal kinase kinase 1(MKK4) [JNKK1(MKK4)] (Dérijard et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995), JNKK2(MKK7) (Wu et al. 1997), MKK3, and MKK6 (Stein et al. 1996). JNKK1(MKK4) activates both JNK and p38 MAPKs (Dérijard et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995), whereas JNKK2(MKK7) is a specific JNK activator (Holland et al. 1997; Tournier et al. 1997; Wu et al. 1997) and MKK3 and MKK6 are specific p38 activators (Dérijard et al. 1995; Raingeaud et al. 1996; Stein et al. 1996). Therefore, MEKK1, and probably other family members, such as MEKK2 and MEKK3 (Blank et al. 1996), can potentially activate at least three MAPK modules. Controlled expression of truncated MEKK1, however, results in much more efficient activation of JNKs than ERKs (Minden et al. 1994; Yan et al. 1994). Another similarity between MEKK1 and Ste11 is that once isolated from the cell, both are constitutively active (Rhodes et al. 1990; Neiman and Herskowitz 1994; Xu et al. 1996). Therefore, it is essentially impossible to biochemically demonstrate their activation by distinct upstream inputs.

We investigated how MEKK1 can activate distinct MAPK modules. When expressed at low levels, MEKK1 is a highly efficient JNK activator and a somewhat less efficient p38 activator. Weak ERK activation is observed only on vast overexpression of MEKK1. The preference toward JNK (and p38) is attributable to a highly specific interaction between MEKK1 and JNKK1. None of the other MAPKKs can stably interact with MEKK1. The MEKK1:JNKK1 complex, however, is disrupted once JNKK1 is activated. JNKK1, on the other hand, can specifically interact with JNK and p38 but not with ERK. Competition experiments suggest that JNK (and p38) compete with MEKK1 for binding to JNKK1 and both interactions require the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1, which is not a part of its catalytic domain. These interactions are biologically relevant because inactive JNKK1 mutants can interfere with JNK activation in intact cells by certain upstream stimuli only if they contain an intact amino-terminal extension. Furthermore, mutations in the amino-terminal extension differentially affect the ability of JNKK1 to respond to upstream stimuli.

Results

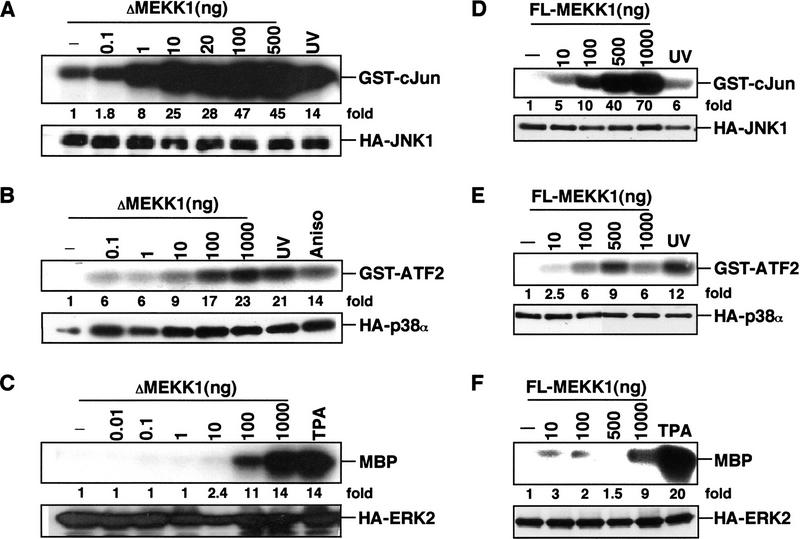

Full-length and truncated MEKK1 preferentially activate JNK and p38

The ability of transiently expressed MEKK1 to activate MAPKs has been studied mainly by expression of its catalytic domain (ΔMEKK1), which at low expression levels activates the JNKs but not the ERKs (Minden et al. 1994; Yan et al. 1994; Lin et al. 1995). To determine the specificity of native MEKK1, we isolated overlapping cDNAs encompassing the entire open reading frame (ORF) of human MEKK1 (Y. Xia and B. Su, unpubl.; sequence available under GenBank accession no. AF042838). Human MEKK1 is 83% identical to rat MEKK1 (Xu et al. 1996) and is composed of 1495 amino acids. We constructed a full-length (FL) MEKK1 expression vector specifying a 200-kD polypeptide and several proteolytic products (see Fig. 4A, below). We compared the ability of this vector to activate JNK, p38, and ERK in mammalian cells with that of a ΔMEKK1 vector. Increasing amounts of ΔMEKK1 or FL-MEKK1 were coexpressed transiently with a representative of each of the MAPK subgroups (JNK1, p38α, or ERK2) tagged with an amino-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) epitope. The MAPKs were isolated by immunoprecipitation and their activities were determined by immunecomplex kinase assays. Both ΔMEKK1 and FL-MEKK1 exhibited the same selectivity in MAPK activation (Fig. 1). At low inputs (10–100 ng of MEKK1 DNA), MEKK1 activated JNK1 very robustly and p38α somewhat less efficiently. At these levels, MEKK1 had only a marginal effect on ERK2 activity. Similar results were obtained in HEK293 cells (data not shown). These results confirmed that MEKK1 preferentially activates JNK1 and to a lesser extent p38α, but is ineffective in ERK2 activation. This selectivity is intrinsic to the carboxy-terminal catalytic domain of MEKK1 and is not modified by its amino-terminal extension. A lesser amount of the ΔMEKK1 expression vector is needed to activate JNK or p38 than the FL-MEKK1 vector because the catalytic domain is expressed more efficiently (data not shown).

Figure 4.

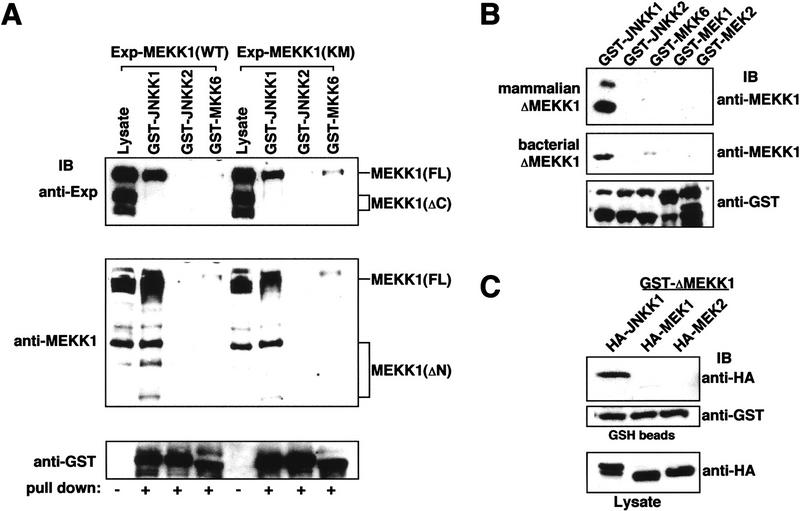

MEKK1 binds to JNKK1. (A) Full-length MEKK1 specifically interacts with JNKK1 through its carboxy-terminal kinase domain. GST–MAPKK fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified. Equal amounts of each protein were mixed with lysates of transfected Cos-1 cells containing transiently expressed wild-type (WT) or catalytically inactive (KM) MEKK1 with an amino-terminal Express epitope. The proteins were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Express (top), anti-MEKK1 directed against the carboxy-terminal kinase domain (middle), or anti-GST (bottom). (B) Purified recombinant JNKK1 specifically and directly interacts with MEKK1. Purified, recombinant GST–MAPKK fusion proteins were mixed with lysates of cells expressing ΔMEKK1 (top) or with purified His–ΔMEKK1 expressed in E. coli (middle). The proteins were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK1 or anti-GST (bottom). (C) Binding of JNKK1 to purified ΔMEKK1. Purified recombinant GST–ΔMEKK1 was mixed with Cos-1 cell lysates containing equal amounts of transiently expressed HA–JNKK1, HA–MEK1, or HA–MEK2 determined by anti-HA immunoblotting (bottom). The proteins were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (top) or anti-GST (middle).

Figure 1.

MEKK1 selectively activates JNK and p38. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for HA-tagged JNK1 (A,D), p38α (B,E), or ERK2 (C,F), together with increasing amounts (in ng) of either ΔMEKK1 (A,B,C) or FL-MEKK1 (D,E,F) vectors. After 48 hr, 10-μg samples of transfected cell lysates were used to determine MAPK expression by immunoblotting with anti-HA (bottom panels). Fifty-microgram samples were subjected to immunecomplex kinase assays using anti-HA and appropriate recombinant proteins as substrates (top panels). Fold stimulations of MAPK activities were calculated after phosphoimaging and normalization for MAPK expression levels. As a reference, JNK1 was stimulated by UV irradiation (40 J · m−2), p38α by UV irradiation or anisomycin (1 μg/ml), and ERK2 by treatment with phorbol ester (TPA, 10 ng/ml).

MEKK1 preferentially activates JNKK1 in cells and in vitro

To identify which MAPKKs respond to MEKK1, vectors encoding HA-tagged JNKK1 (Dérijard et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995), MKK3 (Dérijard et al. 1995), MKK6 (Raingeaud et al. 1996; Stein et al. 1996), MEK1, and MEK2 (Crews et al. 1992) were coexpressed with increasing amounts of ΔMEKK1. MAPKK activity was determined by immunecomplex kinase assays. At low input (1 ng of ΔMEKK1 DNA or less), MEKK1 exhibited strong preference for JNKK1 activation (Fig. 2A). Even JNKK2 was not effectively stimulated at this input level (data not shown). At higher inputs (10–100 ng of ΔMEKK1 DNA), MEKK1 also activated the other MAPKKs, but JNKK1 was still the most responsive (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that JNKK1 is most likely the preferred MAPKK target for MEKK1 in cells.

Figure 2.

JNKK1 is the preferred MAPKK substrate for MEKK1. (A) MEKK1 preferentially activates JNKK1 in mammalian cells. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with increasing amounts of ΔMEKK1, together with HA-tagged MAPKKs. Immunoblot analyses and immunecomplex kinase assays were performed as described in Fig. 1, using recombinant, catalytically inactive MAPKs as substrates. Fold stimulations of MAPKK activities were calculated as in Fig. 1 and are indicated below each autoradiograph. As references, JNKK1, MKK3, and MKK6 activities were stimulated by UV irradiation of transfected cells, and MEK1/2 by TPA treatment. (B) JNKK1 is the preferred MAPKK substrate for MEKK1 in vitro. Kinase assays (see Materials and Methods) were performed using purified recombinant GST–ΔMEKK1 as the kinase and purified recombinant GST–MAPKK fusion proteins, as well as JNKK1 truncation mutants—JNKK1(78–399) or JNKK1(89–399)—as substrates. Incorporation of 32P was determined by scintillation counting. Data were corrected for MAPKK autophosphorylation and fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation. (Inset) The substrate specificity constants (Vmax/Km).

To examine further the specificity of MEKK1 activity, phosphorylation of different MAPKKs was studied in vitro using recombinant purified GST-tagged ΔMEKK1 as the kinase and purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)–MAPKK fusion proteins as substrates. Despite the use of GST moieties on both the kinase and the substrate it is unlikely that these moieties greatly alter the interaction between the two because they are engaged in formation of very stable homodimers and cannot mediate heterotetramerization (Wallace et al. 1998). Figure 2B shows that JNKK1 is the preferred substrate for MEKK1. The Km value of the MEKK1–JNKK1 reaction is ∼0.2 μm. Although the exact Km value may be somewhat affected by the dimeric state of the enzyme and substrates produced as GST fusion proteins, the specificity constant (Vmax/Km) for JNKK1 phosphorylation is ninefold higher than the specificity constant for JNKK2, the second-most efficient target for MEKK1. We also examined the ability of MEKK1 to phosphorylate two JNKK1 deletion mutants lacking its first 77 or 88 amino acids. Surprisingly, although the sites phosphorylated by MEKK1 are within the catalytic domain of JNKK1 (Dérijard et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995), these mutants, JNKK1(78–399) and JNKK1(89–399), were poorly phosphorylated by MEKK1 (Fig. 2B). Although JNKK1(89–399) was devoid of kinase activity and therefore may be improperly folded, JNKK1(78–399) is an active kinase that responds to certain upstream stimuli (see Fig. 8, below).

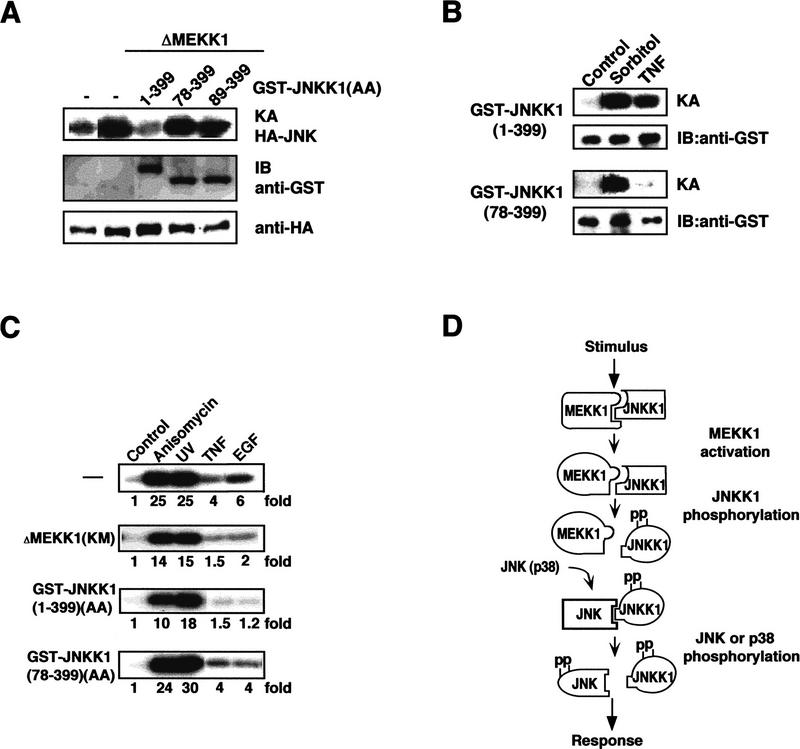

Figure 8.

The amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for transducing upstream stimuli to JNK in intact cells. (A) The amino-terminal extension is required for inhibition of JNK activation by dominant-negative JNKK1. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA–JNK2 and ΔMEKK1 expression vectors, along with either empty expression vector (−) or expression vectors for FL(1–399) GST–JNKK1(AA) or amino-terminally truncated (78–399 and 89–399) GST–JNKK1(AA). After 48 hr, JNK activity was determined by immunecomplex kinase assays (KA) using anti-HA antibody and GST–c-Jun(1–79) as a substrate (top panel). The content of GST–JNKK1(AA) proteins and HA–JNK2 was determined by immunoblotting (IB; bottom two panels). (B) The amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for response to stimuli. HeLa cells were transfected with expression vectors for either FL(1-399) or amino-terminally truncated (78–399) GST–JNKK1. After 48 hr, the cells were incubated with either 0.4 m sorbitol (osmotic shock) or 20 ng/ml of TNF for 20 min. Cell lysates were prepared, the GST–JNKK1 proteins were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose, and their kinase activities were determined. (C) The amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for inhibition of JNK activation in response to physiological stimuli. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA–JNK2 and either an empty vector (−) or expression vectors for catalytically inactive ΔMEKK1 [MEKK1(KM)] and either FL(1–399) or amino-terminally truncated (78–399) GST–JNKK1(AA). After 40 hr, the cells were exposed to anisomycin (15 ng/ml), UV-C (20 J · m−2), TNF (5 ng/ml), or EGF (20 ng/ml). Lysates were prepared after 20 min and HA–JNK2 kinase activity was determined as described above. (D) A sequential-interaction model for organization of the MEKK1–JNKK1–JNK(p38) MAPK module. MEKK1, either active or inactive, interacts with inactive JNKK1 to form a MEKK1:JNKK1 complex, whose formation depends on the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1. Activated MEKK1 phosphorylates and activates JNKK1, resulting in dissociation of the MEKK1:JNKK1 complex. Activated JNKK1 then interacts with JNK (or p38) through its amino-terminal extension. JNK (or p38) activation is followed by dissociation of the JNKK1:JNK complex and activated JNK is freed to bind its targets and phosphorylate them.

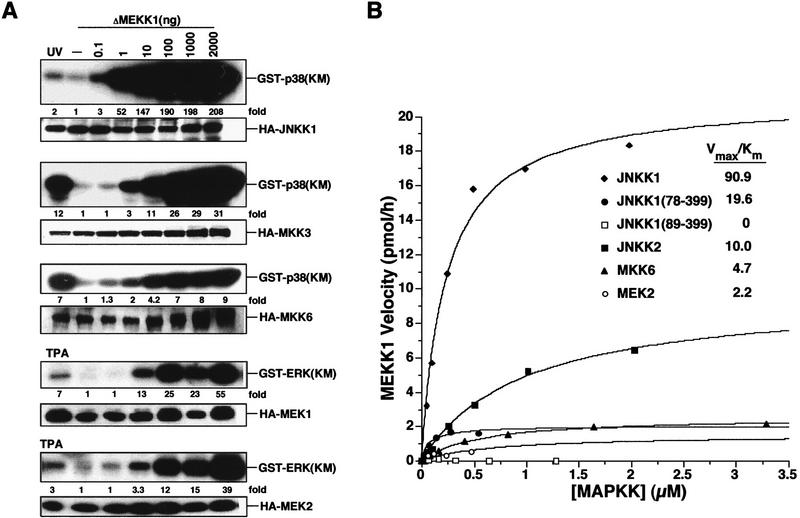

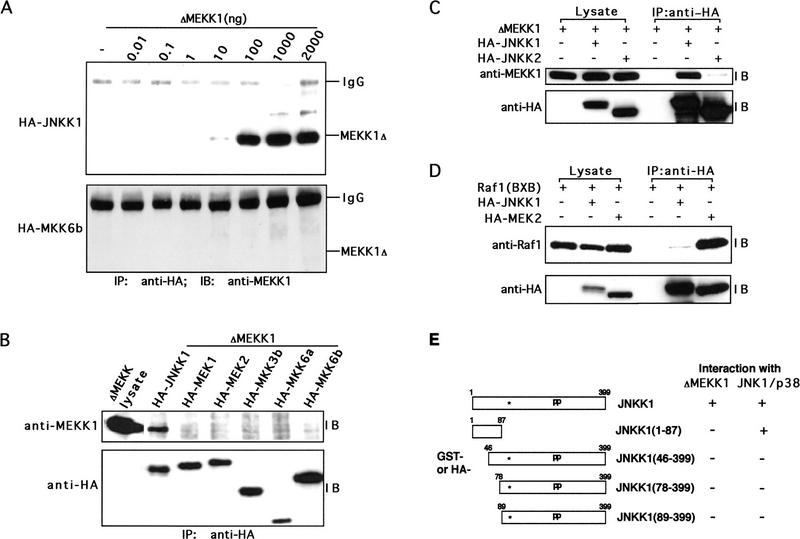

MEKK1 directly and specifically interacts with JNKK1

In addition to conventional enzyme:substrate interactions, components of signaling pathways tend to form stable complexes, whose formation has an important role in determining specificity (Avruch et al. 1994; Bax and Jhoti 1995; Cohen et al. 1995; Kallunki et al. 1996). To explore whether such interactions determine the specificity of MEKK1 action, we performed coprecipitation experiments. Lysates of the same cells in which we screened the response of MAPKKs to MEKK1 (Fig. 2A) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA and coprecipitation of MEKK1 was examined by immunoblotting. Only HA–JNKK1 formed a stable complex with ΔMEKK1 (Fig. 3A, top panel). None of the other MAPKKs, including MEK1, MEK2, MKK3, MKK6, and even JNKK2, interacted with ΔMEKK1 under these conditions (Fig. 3A,C; data not shown). The specificity of these interactions was further studied by mixing cell lysates containing ΔMEKK1 with lysates containing each of the HA–MAPKKs and a coprecipitation assay. Again, only JNKK1 formed stable complexes with MEKK1 that could be precipitated by anti-HA (Fig. 3B). Similar specificity was exhibited by FL-MEKK1 and immunoprecipitation of endogenous JNKK1 resulted in coprecipitation of transiently expressed FL-MEKK1 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

JNKK1 specifically interacts with MEKK1. (A) JNKK1, but not MKK6, forms stable complexes with MEKK1. Lysates of Cos-1 cells cotransfected with the indicated amounts of ΔMEKK1 and either HA–JNKK1 or HA–MKK6b expression vectors were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HA. The precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-MEKK1. The efficiencies of HA–JNKK1 and HA–MKK6 expression were similar (data not shown). (B) JNKK1, but not other MAPKKs, interacts with MEKK1. Lysates of Cos-1 cells transiently expressing HA–MAPKKs were mixed with lysates containing ΔMEKK1. The mixtures were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA, the immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted sequentially with anti-MEKK1 (top) and anti-HA (bottom). (C) JNKK1, but not JNKK2, interacts with MEKK1. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with ΔMEKK1 and either HA–JNKK1, HA–JNKK2, or empty expression vector. Cell lysates were either directly separated by SDS-PAGE or immunoprecipitated with anti-HA as indicated and then resolved by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblot analyses were performed with anti-MEKK1 (top) or anti-HA (bottom). (D) Raf-1 interacts with MEK2 but not with JNKK1. Cos-1 cells were transfected with Raf1(BXB), HA–JNKK1, and HA–MEK2 expression vectors, as indicated. Cell lysates were analyzed as described in A. Protein expression was evaluated by separating one-fortieth of each lysate directly by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-Raf-1 (top) or anti-HA (bottom) antibodies. The same antibodies were used for immunoblotting of anti-HA immunoprecipitates. (E) Amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for interacting with MEKK1 and JNKs(p38). Schematic representation of JNKK1 deletion mutants with either GST or HA tags at their amino termini. The location of the ATP-binding site is indicated by an asterisk and the activating phosphoacceptor sites by pp. GST-tagged full-length and truncated JNKK1 proteins were expressed either in Cos-1 cells or in bacteria and their binding to ΔMEKK1, JNK, and p38 was examined by in-vitro mixing–coprecipitation assays, as described in B. The results are indicated on the right.

To investigate the specificity of MEKK1:JNKK1 interaction, coprecipitation of other MAPKKKs, including Raf-1 (Dent et al. 1992), ASK (Ichijo et al. 1997), NIK (Malinin et al. 1997), and GCK (Pombo et al. 1995), with JNKK1 was examined. None of these MAPKKKs could be coprecipitated with JNKK1 (Fig. 3D; data not shown). Raf-1 is the MAPKKK for MEK1/MEK2 (Dent et al. 1992). Correspondingly, the catalytic domain of Raf-1 was efficiently coprecipitated with MEK2, but not with JNKK1 (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that the specificity of MEKK1 toward JNK and p38 is achieved through specific association with JNKK1. Moreover, MAPKKK: MAPKK interactions may represent a general mechanism for determining the specificity of MAPKKK action.

To define the part of JNKK1 that interacts with MEKK1, deletion mutants of JNKK1 were constructed and expressed in Cos-1 cells as HA-tagged or GST fusion proteins (Fig. 3E). Cell lysates containing different HA–JNKK1 derivatives were mixed with cell lysates containing ΔMEKK1 and the mixtures were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies. Coprecipitation of ΔMEKK1 was determined by immunoblotting. Only full-length JNKK1 stably interacted with ΔMEKK1 and the mere deletion of only 45 amino acids from its amino-terminal extension was sufficient to abolish this interaction (Fig. 3E). These results together with the relative phosphorylation of the JNKK1 derivatives by MEKK1 (Fig. 2B; data not shown) indicate that an intact amino-terminal extension is required for a stable interaction between JNKK1 and MEKK1 and for efficient JNKK1 phosphorylation and activation. On its own, however, the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is not sufficient for stable binding to MEKK1 (Fig. 3E).

GST–MAPKK fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and examined for their ability to precipitate amino-terminally Express(Exp)-tagged FL-MEKK1 and its derivatives from transfected cell extracts. Immunoblot analysis with anti-Express detected a 200-kD FL-Exp–MEKK1 polypeptide and two carboxy-terminally truncated forms (ΔC), 150 and 120 kD in size (Fig. 4A, top). Only the 200-kD form, which contains an intact carboxy-terminal kinase domain, interacted with GST–JNKK1. Very little binding of this form to GST–JNKK2 or GST–MKK6 was observed. As similar interactions were displayed by catalytically inactive MEKK1(KM) mutant, MEKK1 kinase activity is not required for binding to JNKK1. An antibody directed to the carboxy-terminal kinase domain of MEKK1 (anti-MEKK1) detected the full-length MEKK1 polypeptide and several amino-terminally truncated forms (ΔN), the major one being 90 kD in size (Fig. 4A, middle). Both this form and the full-length form were precipitated by GST–JNKK1 but not by GST–JNKK2 or GST–MKK6. Although the amino-terminal portion of MEKK1 is not necessary for binding to JNKK1, it is likely to be involved in interactions with upstream signaling proteins (Su et al. 1997).

We also compared binding of either ΔMEKK1 expressed in Cos-1 cells (mammalian ΔMEKK1) presented as a crude lysate or purified E. coli-expressed ΔMEKK1 (bacterial ΔMEKK1) to different bacterially expressed and purified GST–MAPKK proteins (Fig. 4B). Only JNKK1 was able to bind ΔMEKK1, regardless of its source. As this interaction was exhibited between two purified, bacterially expressed proteins, we conclude that JNKK1, but not other MAPKKs, binds directly to the catalytic domain of MEKK1. Specific interaction between ΔMEKK1 and JNKK1 was also observed when E. coli-expressed and purified GST–ΔMEKK1 were used to precipitate various HA–MAPKKs expressed in Cos-1 cells (Fig. 4C).

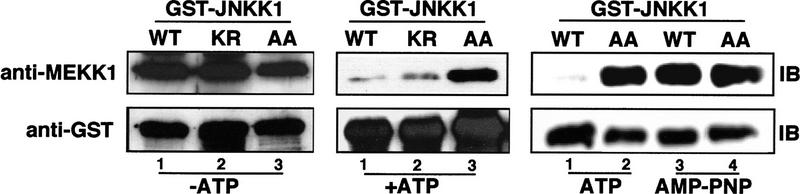

JNKK1 phosphorylation disrupts its interaction with MEKK1

The effect of JNKK1 activation on its interaction with MEKK1 was studied by comparing the binding of MEKK1 with wild-type JNKK1 and two mutants—JNKK1(KR), which is defective in ATP binding and therefore catalytically inactive, and JNKK1(AA), which can bind ATP but cannot be activated by MEKK1 because it lacks the activating phosphoacceptor sites (Lin et al. 1995). In the absence of ATP or in the presence of nonhydrolyzable ATP analog adenylyl-imidodiphosphate, tetralithium salt (AMP–PNP), all three forms of JNKK1 bound MEKK1 equally well (Fig. 5). When ATP was included and the mixture was preincubated to allow phosphorylation of JNKK1 prior to the precipitation precedure, however, wild-type JNKK1 and JNKK1(KR) bound MEKK1 much less efficiently than JNKK1(AA). These results indicate that phosphorylation of JNKK1 by MEKK1 either weakens its association with MEKK1 or promotes complete dissociation of the complex.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of JNKK1 disrupts its binding to ΔMEKK1. GST-fusion proteins containing wild-type JNKK1, an ATP-binding mutant, JNKK1 (KR), or a mutant lacking the activating phosphoacceptor sites, JNKK1(AA), were transiently expressed in Cos-1 cells. Lysates containing these proteins were mixed with ΔMEKK1-containing lysates and incubated for 20 min at 30°C in kinase buffer without ATP or with 1 mm ATP or AMP–PNP as indicated. Next, the GST fusion proteins were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose. After washing six to eight times, the precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-MEKK1 (top) and anti-GST (bottom).

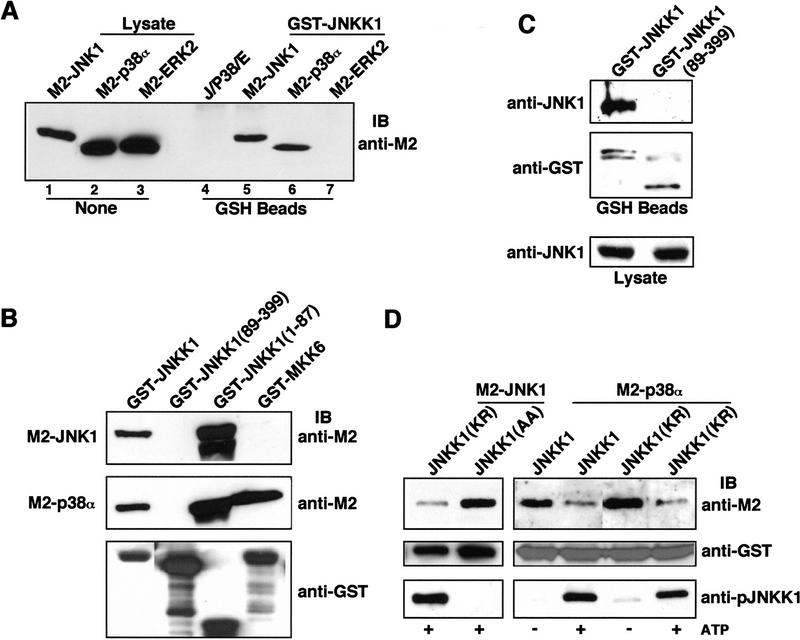

JNKK1 specifically interacts with JNK and p38, but not with ERK

We also examined the interaction of JNKK1 with various MAPKs. Similar amounts of transiently expressed M2-tagged JNK1, ERK2, or p38α were mixed with cell lysates containing GST–JNKK1 and the mixtures were precipitated with glutathione–Sepharose (GSH). Immunoblotting revealed that GST–JNKK1 interacted stably with JNK1 and p38α, but not with ERK2 (Fig. 6A). No precipitation of any of the MAPKs occurred in the absence of GST–JNKK1. In addition, transfected cell lysates containing M2–JNK1 or M2–p38α were subjected to precipitation with GSH beads after mixing with bacterially expressed GST fusion proteins containing either FL-JNKK1, its catalytic domain JNKK1(89–399), its amino-terminal extension JNKK1(1–87), or MKK6. JNK1 was precipitated by GST–JNKK1 but not GST–JNKK1(89–399) or GST–MKK6 (Fig. 6B). p38α, however, was precipitated by both GST–JNKK1 and GST–MKK6, but not by GST–JNKK1(89–399). Interestingly, both JNK1 and p38α formed stable complexes with the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1, JNKK1(1–87). More extensive deletion analysis revealed that removal of only 43 amino acids from the amino terminus of JNKK1 abolished JNK or p38α binding (Fig. 3E; data not shown). Therefore, in the case of the JNKK1:JNK (or p38) interaction, the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is necessary and sufficient.

Figure 6.

JNKK1 specifically interacts with JNK1 and p38α. (A) JNKK1 stably interacts with JNK1 and p38α, but not with ERK2. Lysates (10 μg) of Cos-1 cells transfected with M2-tagged MAPK vectors were examined for MAPK expression by immunoblotting with anti-M2 (lanes 1–3). Lysates (400 μg) were also mixed with lysates containing GST–JNKK1, precipitated with GST–Sepharose, and immunoblotted with anti-M2. In addition, equal amounts of lysates containing each of the MAPKs were mixed and examined for binding to GSH–Sepharose in the absence of GST–JNKK1 (lane 4). (B) JNKK1 interacts with both JNK1 and p38α through its amino-terminal extension. Lysates containing M2–JNK1 or M2–p38α were mixed with purified, recombinant GST–JNKK1, GST–JNKK1(89–399), GST–JNKK1(1–87), or GST–MKK6. After precipitation with GSH–Sepharose and separation by SDS-PAGE, the precipitated proteins were immunoblotted with anti-M2 (top two panels) or anti-GST (bottom panel). (C) JNKK1 binds endogenous JNK1. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with either GST–JNKK1 or GST–JNKK1(89–399) expression vectors. Cell lysates were prepared, precipitated with GSH–Sepharose, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-JNK1 or anti-GST. A small fraction ( ) of each lysate was directly analyzed for its content of JNK1. (D) Lysates of Cos-1 cells expressing GST–JNKK1, GST–JNKK1(KR), or GST–JNKK1(AA) were incubated with a small amount of lysate containing ΔMEKK1 in kinase buffer in the absence or presence of 1 mm ATP. Then, lysates containing similar amounts of M2–JNK1 (left panels) or M2–p38α (right panels) were added. The mixtures were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose followed by immunoblotting with anti-M2 (top panels), anti-GST (middle panels), or anti-phospho-JNKK1 (bottom panels).

) of each lysate was directly analyzed for its content of JNK1. (D) Lysates of Cos-1 cells expressing GST–JNKK1, GST–JNKK1(KR), or GST–JNKK1(AA) were incubated with a small amount of lysate containing ΔMEKK1 in kinase buffer in the absence or presence of 1 mm ATP. Then, lysates containing similar amounts of M2–JNK1 (left panels) or M2–p38α (right panels) were added. The mixtures were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose followed by immunoblotting with anti-M2 (top panels), anti-GST (middle panels), or anti-phospho-JNKK1 (bottom panels).

JNKK1 also interacts with endogenous JNK. HEK293 cells were transfected with either GST–JNKK1 or GST–JNKK1(89–399) vectors and cell lysates were precipitated with GSH beads. Immunoblotting with anti-JNK1 revealed that GST–JNKK1, but not GST–JNKK1(89–399), interacts with endogenous JNK1 (Fig. 6C).

We examined the effect of JNKK1 phosphorylation on binding to JNK and p38. GST–JNKK1, GST–JNKK1(KR), or GST–JNKK1(AA) were incubated with ΔMEKK1 in the absence or presence of ATP and examined for binding to M2–JNK1 or M2–p38α by GST pull-down. Immunoblotting with anti-M2 revealed that JNK1 or p38α interacted with phosphorylated JNKK1 somewhat less efficiently than with nonphosphorylated JNKK1 (Fig. 6D). Nevertheless, the effect of JNKK1 activation on binding to JNK or p38 was far less dramatic than its disruptive effect on binding to MEKK1 (cf. Figs. 6D and 5).

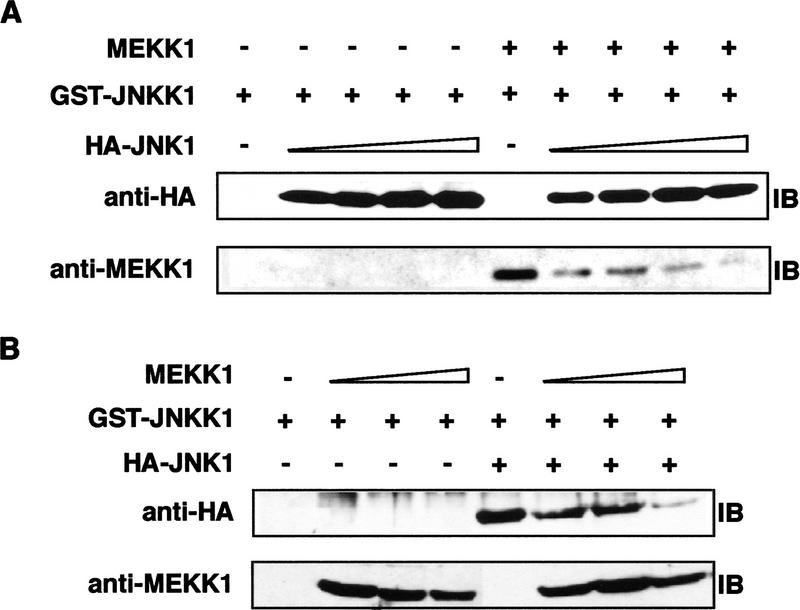

MEKK1 and JNK compete for binding to JNKK1

The amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for binding to either MEKK1 or to JNK and p38. We asked whether MEKK1, JNKK1, and JNK1 form a stable ternary complex. Fixed amounts of a cell lysate containing GST–JNKK1 were mixed with a fixed amount of a ΔMEKK1 containing lysate and then increasing amounts of HA–JNK1 were added. GST pull-down experiments revealed that as the amount of JNK1 increased, the amount of MEKK1 bound to JNKK1 decreased (Fig. 7A). Similar results were obtained when the amount of HA–JNK1 incubated with GST–JNKK1 was fixed and increasing amounts of ΔMEKK1 were added (Fig. 7B). We also obtained similar results when HA–p38α was used instead of HA–JNK1 (data not shown). As JNK does not interact directly with MEKK1 (data not shown), these results suggest that MEKK1 and JNK (or p38α) are unlikely to bind simultaneously to JNKK1.

Figure 7.

ΔMEKK1 and JNK compete for binding to JNKK1. (A) Cell lysates containing GST–JNKK1 or a mixture of GST–JNKK1 lysate with ΔMEKK1-containing lysate were mixed with increasing amounts of HA–JNK1-containing lysates. The mixtures were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-HA (top) and anti-MEKK1 (bottom). (B) Lysates containing GST–JNKK1 were mixed with increasing amounts of ΔMEKK1-containing lysates in the absence or presence of HA–JNK1-containing lysates. The mixtures were precipitated with GSH–Sepharose and analyzed as described above.

The amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 is required for inhibition of JNK activation and responsiveness to physiological activators

To examine the role of the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 in physiological signal transduction, we tested the ability of FL-JNKK1(AA) or its amino-terminally truncated derivatives thereof to interfere with JNK activation in intact cells. Transient expression of a small amount of ΔMEKK1 results in JNK activation, which is inhibitable by a FL(1–399) GST–JNKK1(AA) mutant (Fig. 8A). JNK activation, however, was not inhibited on coexpression of equal amounts of amino-terminally truncated (78–399 or 89–399) GST–JNKK1(AA) mutants. These truncation mutants either failed to respond or responded poorly to coexpression of MEKK1 (data not shown).

We also compared the ability of FL(1–399) and truncated (78–399) GST–JNKK1 fusion proteins to respond to upstream stimuli. Whereas the kinase activity of FL-GST–JNKK1 was stimulated by both sorbitol and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), GST–JNKK1(78–399) was activated by sorbitol but not TNF (Fig. 8B). The amino-terminal deletion also had little effect on the responses to other stress stimuli—UV and anisomycin (data not shown). The ability of inactivatable derivatives of the two JNKK1 constructs, FL-GST–JNKK1(AA) and (78–399) GST–JNKK1(AA), to interfere with JNK activation by upstream stimuli was also examined (Fig. 8C). As described previously (Minden et al. 1995), the activation of HA–JNK2 by TNF or epidermal growth factor (EGF) was inhibited almost completely by coexpression of catalytically inactive ΔMEKK1(KM). This mutant only partially inhibited the responses to anisomycin or UV radiation. A similar inhibitory effect was caused by coexpression of FL-GST–JNKK1(AA). Coexpression of a similar amount of truncated (78–399) GST–JNKK1(AA), however, did not significantly interfere with JNK activation by any of these stimuli.

Discussion

Eukaryotic cells use MAPK cascades to transfer information from cell-surface receptors to transcription factors in the nucleus and other important regulatory molecules (Herskowitz 1995; Hill and Triesman 1995; Karin and Hunter 1995; Marshall 1995). The existence of multiple MAPKs, MAPKKs, and MAPKKKs within a single cell raises an important and not thoroughly explored problem regarding the specificity of MAPK activation and action. We investigated how specific activation of the JNK cascade is achieved. Although the MAPKKK MEKK1 was originally identified as a MEK kinase (hence, the name MEKK) that activates MEK1/MEK2 (Lange-Carter et al. 1993; Xu et al. 1996) (Fig. 2), when expressed at modest levels, MEKK1 does not cause considerable ERK activation. Instead, it is a highly efficient activator of the JNK cascade (Minden et al. 1994; Yan et al. 1994). By comparing the ability of MEKK1 to activate various MAPKKs, we found that JNKK1 is the preferred substrate for MEKK1. Similar results were obtained in vitro and the specificity constant for JNKK1 phosphorylation by MEKK1 is at least 10-fold higher than the specificity constant for any other MAPKK. The preferential phosphorylation and activation of JNKK1 by MEKK1 correlates with specific formation of MEKK1:JNKK1 complexes. None of the other mammalian MAPKKs that we examined can interact stably with MEKK1. This specificity is underscored by the failure of JNKK2(MKK7), which is also a JNK kinase (Holland et al. 1997; Tournier et al. 1997; Wu et al. 1997), and MKK3 or MKK6, which are specific p38 kinases (Dérijard et al. 1995; Stein et al. 1996), to interact with MEKK1. JNKK1 did not bind to MAPKKKs other than MEKK1, including ASK, NIK, and Raf-1. We did, however, detect stable interaction between Raf-1 and MEK2. The stable interaction between MEKK1 and JNKK1 is functionally important because it is abolished by short deletions removing the first 45 amino acids of JNKK1, which also interfere with the phosphorylation of JNKK1 and its activation by MEKK1 or certain physiological stimuli, such as TNF. These deletions, however, do not remove the phosphoacceptor sites recognized by MEKK1, which are located within the catalytic domain of JNKK1 (Lin et al. 1995) and most importantly, do not abolish activation of JNKK1 by physical and chemical stresses. As purified recombinant MEKK1 and JNKK1 also form a stable complex, the interaction between the two proteins is direct.

The requirement of the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1 for binding to MEKK1 strongly suggests that the complex between the two is not a standard enzyme:substrate complex formed by an interaction between the catalytic pocket of MEKK1 with the activation loop (which contains the phosphoacceptor sites) of JNKK1. In fact, substitution of the phosphoacceptor sites with nonphosphorylatable residues does not interfere with binding of JNKK1 to MEKK1 and catalytically inactive MEKK1 binds JNKK1 as efficiently as its wild-type counterpart. The MEKK1:JNKK1 complex is, however, highly sensitive to phosphorylation of JNKK1. Preincubation with ATP allowing phosphorylation of JNKK1 by MEKK1 prevents the coprecipitation of either wild-type or a catalytically inactive JNKK1 mutant, JNKK1(KR). ATP, however, has no effect on binding of a mutant that lacks the activating phosphoacceptor sites, JNKK1(AA), and therefore is not phosphorylated by MEKK1.

We also examined the direct interaction of JNK1 with MEKK1, as it was reported previously that JNK and ERK interact with MEKK1 through the amino-terminal extension of MEKK1 (Xu and Cobb 1997). We found that both JNK1 and ERK2 interacted weakly with FL-MEKK1, but not with ΔMEKK1 (data not shown). Similar weak interactions were also observed between FL-MEKK1 and MKK6 (Fig. 4A). These interactions, however, are much weaker than the interaction between FL-MEKK1 and JNKK1 (Fig. 4A). We therefore conclude it is the MEKK1–JNKK1 interaction rather than the MEKK1–JNK interaction that determines the specificity of this signaling cascade.

The interaction between MEKK1 and JNKK1 is only one component that contributes to formation of a specific JNK MAPK module. We detected stable JNKK1:JNK1 or JNKK1:p38α complexes but no JNKK1:ERK2 complexes. JNK1, on the other hand, interacted with JNKK1 but not with MEK1/2 or MKK6, whereas p38α bound both JNKK1 and MKK6. These interactions are consistent with the specificity of MAPK activation by MAPKKs, because JNKK1(MKK4) activates JNK and p38α (Dérijard et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995), whereas MKK6 activates p38α but not JNK (Han et al. 1996). These results are somewhat different from an earlier report that in mammalian cells JNKK1 could be associated with JNK but not with p38α (Zanke et al. 1996). Using the more sensitive two hybrid system, however, the same authors found that JNKK1 interacted equally well with JNK or p38α and that MKK6 interacts with p38α but not with JNK. The interaction between JNKK1 and p38α is likely to be physiologically relevant, because MEKK1 is also an effective p38 activator (Fig. 1) and so far no major differences in the response of JNK1/2 and p38α to upstream stimuli were observed (Raingeaud et al. 1995; T. Sudu and M. Karin, unpubl.).

The interaction with JNK1 or p38α also requires the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1. In this case, however, amino-terminal extension is sufficient for binding either JNK1 or p38α. Therefore, the interaction with either JNK1 or p38α is also not a classical enzyme:substrate interaction. As both MEKK1 and JNK1 interact with the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1, it is not surprising to find that, at least in vitro, JNK1 and MEKK1 compete for binding to JNKK1 rather than form a ternary complex. It is possible, however, that in the presence of a scaffold protein such a complex does form. Unlike the binding of JNKK1 to MEKK1, which is disrupted by JNKK1 activation, the activation of JNKK1 has only a small effect on binding to JNK1. Based on these results, we offer the simplified sequential interaction model (Fig. 8D) to explain the organization and function of a specific MAPK module consisting of JNK1, JNKK1, and MEKK1. According to this model, active (or possibly inactive) MEKK1 binds JNKK1 in a manner that depends on contacts with its amino-terminal extension. If MEKK1 is active, JNKK1 is phosphorylated and the MEKK1:JNKK1 complex dissociates. Activated JNKK1 is freed to specifically interact with its substrate JNK1 (and p38α) through its amino-terminal extension. Once this complex is formed, the MAPK is activated followed by somewhat slower dissociation of the JNKK1:JNK complex compared with the MEKK1:JNKK1 complex. The activated MAPK is then freed to phosphorylate downstream targets.

This model attributes a major role in determination of signaling specificity to the amino-terminal extension of JNKK1. The physiological role of this part of JNKK1 is demonstrated by several experiments. Short deletions that remove parts of the amino-terminal extension interfere with the ability of JNKK1 to be activated in response to TNF but have little effect on its response to physical and chemical stressors, such as sorbitol (osmotic shock) or UV radiation. Likewise, an intact amino-terminal extension is required for the ability of an inactivatable JNKK1 mutant to interfere with JNK activation by either TNF or EGF.

Is the model presented in Figure 8D consistent with other models proposed to explain the organization of MAPK modules? An extensively studied system is the pheromone-responsive MAPK cascade of yeast (Herskowitz 1995). In this case, functional integrity of the cascade composed of Ste11, Ste7, and Fus3 depends on a fourth component, Ste5 (Choi et al. 1994). Ste5 acts as a scaffold that can simultaneously bind the three other components (Choi et al. 1994; Marcus et al. 1994; Printen and Sprague 1994). By doing so, Ste5 may facilitate information transfer within the module while isolating it from inputs generated by other MAPK modules, thereby preventing potential cross talk (Herskowitz 1995; Levin and Errede 1995). Ste7, however, can interact with Fus3 and Kss1 in the absence of Ste5 and this interaction is also required for optimal functioning of the pheromone-responsive module (Bardwell et al. 1996). Interestingly, the interaction with Fus3 and Kss1 is mediated by the amino-terminal extension of Ste7 (Bardwell et al. 1996). Therefore, a great deal of inherent specificity may exist between different components of the pheromone-responsive module and one of the main roles of Ste5 is to stabilize these interactions further and act as a coactivator. Therefore, the most basic organization of the pheromone-responsive MAPK module may not be all that different from that of the JNK module. In addition, our results do not rule out the existence of a scaffold protein that stabilizes the JNK module further. A greater apparent similarity with the JNK module is, however, exhibited by the osmosensitive Sho1-dependent MAPK module of yeast. In that case, the MAPKK Pbs2 can interact stably with both the MAPK Hog1 and one of its MAPKKKs, which also happens to be Ste11 (Posas and Saito 1997). It was not examined, however, whether the three kinases form a ternary complex and the region of Pbs2 that mediates these interactions was not defined.

Formation of stable complexes that include all the components of a given MAPK module, as proposed for the pheromone-responsive module (Choi et al. 1994; Herskowitz 1995; Levin and Errede 1995), creates a conceptual problem as it prevents signal amplification. It was hypothesized, however, that complexes between Ste5 and components of the pheromone-responsive module are unstable and that the MAPKK and MAPKs associate with Ste5 transiently (Choi et al. 1994). It was even proposed that Ste5 may facilitate the dissociation of the kinases, thereby promoting signal amplification (Elion et al. 1995). On the other hand, stable complexes could be needed to restrict the action of kinases, such as Ste11, which is involved in three different and distinctly regulated MAPK cascades.

Although stable and specific MAPKKK:MAPKK interactions have not been amply described, we find that in addition to the specific MEKK1:JNKK1 interaction, Raf-1 interacts with its target MEK2 but not with JNKK1. This interaction could be mediated by a proline-rich sequence unique to MEK1/2 and is inserted into their kinase domain (Catling et al. 1995). Several stable and specific MAPKK:MAPK interactions, on the other hand, have been documented. In addition to JNKK1:JNK1, JNKK1:p38α and Ste7:Fus3 complexes, MEK:ERK complexes were also described (Fukuda et al. 1997). In this case, the interaction is also mediated by the amino-terminal extension of the MAPKK. Despite the absence of obvious primary sequence homology between the amino-terminal extensions of JNKK1, Ste7, and MEK, the three regions appear to serve the same function. In the future, it would be of interest to determine the structure of these regions and identify the basis for their specific interactions with the corresponding MAPKs and MAPKKKs.

Materials and methods

Reagents, antibodies, cells, and plasmids

Phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (TPA), anisomycin, sorbitol, ATP, and protein A–agarose were from Sigma, AMP–PNP and EGF were from Calbiochem, and TNF was a gift from Chiron. Glutathione (GSH)–Sepharose 4B was purchased from Pharmacia. Anti-HA was purified from ascites fluid of mice bearing hybridoma 12CA5; anti-M2 was from Kodak; anti-MEKK1 (C22), anti-Raf1 (C12), and anti-Express were from Santa Cruz Antibodies; anti-phospho JNKK1 was from Boehringer Mannheim; monoclonal anti-JNK1 (333.8) was from Pharmingen; and anti-GST was a gift from Dr. Ebrahim Zandi (UCSD). HEK293, Cos-1, and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle (DME)–high glucose medium with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO).

The different plasmids were either described previously (Minden et al. 1994, 1995; Cavigelli et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1995; Wu et al. 1997) or constructed by standard recombinant DNA procedures (details available on request). MEKK1 4.7-kb cDNA was isolated from HeLa, B-cell, and Jurkat cDNA libraries. This cDNA was subcloned into pCDNA3.1 (Invitrogene Inc.) in-frame with the Express epitope sequence. The ATP-binding site mutant MEKK1 [MEKK1(K1255M)] was constructed using Chameleon double-stranded, site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

Plasmid DNAs were introduced into mammalian cells using Lipofectamine as suggested by the manufacturer (GIBCO).

Proteins

GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified on GSH–Sepharose (Hibi et al. 1993). GST–ΔMEKK1 contains human MEKK1(1199–1496) in-frame with GST at its amino terminus. The His6–ΔMEKK1 protein contains carboxy-terminal 385 amino acids of human MEKK1 in pRSET (Invitrogene, Inc.) in-frame with the (His)6 tag.

Cell lysates were prepared 40–48 hr after transfection in lysis buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 250 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 3 mm EGTA, 3 mm EDTA, 100 μm Na3VO4, 10% glycerol] for immunecomplex kinase assays or in low salt lysis buffer [50 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol] for coprecipitation and GST pull-down assays.

Coprecipitation and GST pull-down assays

For coprecipitation assays, mixtures of cell lysates and proteins were precleared by incubation with protein A–agarose at 4°C for 30 min using washing buffer [20 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol]. The lysates were then immunoprecipitated with appropriate antibodies and protein A–agarose at 4°C for 2 hr. The beads were then washed six times with washing buffer and the precipitates eluted with sample buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto Immobilon membrane and detected by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham). GST pull-down assays were done in a similar manner except that GSH–Sepharose beads were used instead of protein A–agarose and antibodies.

Protein kinase assays

Immunecomplex kinase assays were performed as described (Minden et al. 1994). The kinetics of MAPKK phosphorylation by ΔMEKK1 were determined by quantifying the amount of 32P incorporation into purified substrates in a discontinuous assay. MEKK1 was preincubated with unlabeled ATP for 30 min, followed by the addition of [γ-32P]ATP (5 μCi/reaction) and GST–MAPKK substrates. Reactions were carried out in 96-well plates for 1 hr at room temperature and terminated by addition of trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The TCA precipitates were collected on 96-well glass-fiber plates (Packard) and analyzed for their 32P content using a Packard TopCount scintillation counter. Data were corrected for MAPKK and ΔMEKK1 autophosphorylation. To obtain kinetic constants, the data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation with a nonlinear least squares method.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Han, Z. Liu, and N. Li for providing expression vectors; E. Zandi for MEKK1 protein and helpful discussions; and B. Errede and T. Hunter for critical comments. We also thank O. Chen for technical assistance and B. Thompson for manuscript preparation. Y.X. and Z.W. were supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Irvington Research Institute and Human Frontier Science Project Organization (HFSPO). Research was supported by HFSPO grant RG-598/96M and National Institutes of Health grant HL 35018.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL karinoffice@ucsd.edu; FAX (619) 534-8158.

References

- Avruch J, Zhang X, Kyriakis J. Raf meets ras: Completing the framework of a signal transduction pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:279–283. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell L, Cook J, Chang E, Cairns B, Thorner J. Signaling in the yeast pheromone response pathway: Specific and high-affinity interaction of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases Kss1 and Fus3 with the upstream MAP kinase kinase Ste7. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3637–3650. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax B, Jhoti H. Protein-protein interactions: putting the pieces together. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1119–1121. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank JL, Gerwins P, Elliott EM, Sather S, Johnson GL. Molecular cloning of mitogen-activated protein/ERK kinase kinases (MEKK) 2 and 3. J Biol Chem. 1996;274:5361–5368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster JL, de Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.7681220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catling AD, Schaeffer H-J, Reuter CWM, Reddy GR, Weber MJ. A proline-rich sequence unique to MEK1 and MEK2 is required for Raf binding and regulates MEK function. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5214–5225. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli M, Dolfi F, Claret FX, Karin M. Induction of c-fos expression through JNK-mediated TCF/Elk-1 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995;14:5957–5964. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KY, Satterberg B, Lyons DM, Elion EA. Ste5 tethers multiple protein kinases in the MAP kinase cascade required for mating in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1994;78:499–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb M, Goldsmith EJ. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GB, Ren R, Baltimore D. Modular binding domains in signal transduction proteins. Cell. 1995;80:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews CG, Alessandrini A, Erickson RL. The primary structure of MEK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ERK gene product. Science. 1992;258:478–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1411546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent P, Hasar W, Haystead T, Vincent L, Roberts T, Sturgill T. Activation of mitogenic activated protein kinase kinase by v-raf in NIH3T3 cells and in vitro. Science. 1992;254:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.1326789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dérijard B, Raingeaud J, Barrett T, Wu IH, Han J, Ulevitch RJ, Davis RJ. Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elion EA, Trueheart J, Fink GR. Fus2 localizes near the site of cell fusion and is required for both cell fusion and nuclear alignment during zygote formation. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1283–1296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Interaction of MAP kinase with MAP kinase kinase: Its possible role in the control of nucleocytoplasmic transport of MAP kinase. EMBO J. 1997;16:1901–1908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwins P, Blank JL, Johnson GL. Cloning of a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, MEKK4, that selectively regulates the c-Jun amino terminal kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8288–8295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee J-D, Jiang Y, Li Z, Feng L, Ulevitch RJ. Characterization of the structure and function of a novel MAP kinase kinase (MKK6) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2886–2891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz I. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: For mating and more. Cell. 1995;80:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M, Lin A, Smeal T, Minden A, Karin M. Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:2135–2148. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CS, Triesman R. Transcriptional regulation by extracellular signals: Mechanisms and specificity. Cell. 1995;80:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P, Suzanne M, Campbell J, Noselli S, Cooper J. MKK7 is a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase functionally related to hemipterous. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24994–24998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of Apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallunki T, Deng T, Hibi M, Karin M. c-Jun can recruit JNK to phosphorylate dimerization partners via specific docking interactions. Cell. 1996;87:929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Hunter T. Transcriptional control by protein phosphorylation: Signal transmission from cell surface to the nucleus. Curr Biol. 1995;5:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Carter CA, Pleiman C, Gardner A, Blumer K, Johnson G. A divergence in the MAP kinase regulatory network defined by MEK kinase and Raf. Science. 1993;260:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.8385802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D, Errede B. The proliferation of MAP kinase signaling pathways in yeast. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Minden A, Martinetto H, Claret FX, Lange-Carter C, Mercurio F, Johnson GL, Karin M. Identification of a dual specificity kinase that activates the Jun kinases and p38-Mpk2. Science. 1995;268:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.7716521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani HD, Styles CA, Fink GR. MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:673–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Takekawa M, Saito H. Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science. 1995;269:554–558. doi: 10.1126/science.7624781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinin NL, Bolden MP, Kovalenko AV, Wallach D. MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-kappaB induction by TNF, CD95 and IL-1. Nature. 1997;385:540–544. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais R, Light Y, Paterson H, Mason C, Marshall C. Differential regulation of Raf-1, A-Raf, and B-Raf by oncogenic ras and tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4378–4383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S, Polverino A, Barr M, Wigler M. Complexes between STE5 and components of the pheromone-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase module. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:7762–7766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine signaling: Transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minden A, Lin A, McMahon M, Lange-Carter C, Dérijard B, Davis RJ, Johnson GL, Karin M. Differential activation of ERK and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science. 1994;266:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7992057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minden A, Lin A, Claret FX, Abo A, Karin M. Selective activation of the JNK signaling cascade and c-Jun transcriptional activity by the small GTAPases Rac and Cdc42Hs. Cell. 1995;81:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A, Herskowitz I. Reconstitution of a yeast protein kinase cascade in vitro: Activation of the yeast MEK homologue STE7 by STE11. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:3398–3402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombo CM, Kehrl JH, Sanchez I, Katz P, Avruch J, Zon LI, Woodgett JR, Force T, Kyriakis JM. Activation of the SAPK pathway by the human STE20 homologue germinal centre kinase. Nature. 1995;377:750–754. doi: 10.1038/377750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas F, Saito H. Osmotic activation of the HOG MAPK pathway via Ste11p MAPKKK: Scaffold role of PBS2p MAPKK. Science. 1997;276:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Printen JA, Sprague GF., Jr Protein-protein interactions in the yeast pheromone response pathway: Ste5p interacts with all members of the MAP kinase cascade. Genetics. 1994;138:609–619. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingeaud J, Gupta S, Rogers JS, Dickens M, Han J, Davis RJ. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7420–7426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingeaud J, Whitmarsh AJ, Barrett T, Dérijard B, Davis RJ. MKK3 and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1247–1255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes N, Connell L, Errede B. STE11 is a protein kinase required for cell-type-specific transcription and signal transduction in yeast. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:1862–1874. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RL, Fink GR. Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: Mating and invasive growth. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2974–2985. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein B, Brady H, Yang MK, Young DB, Barbosa MS. Cloning and characterization of MEK6, a novel member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11427–11433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y-C, Han J, Xu S, Cobb MH, Skolnik EY. NIK is a new Ste20-related kinase that binds NCK and MEKK1 and activates the SAPK/JNK cascade via a conserved regulatory domain. EMBO J. 1997;16:1279–1290. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbles LA, Ing YL, Kiefer F, Chan J, Iscove N, Woodgett JR, Lassam NJ. MLK-3 activates the SAP/JNK and -38/RK pathways via SEK1 and MEK3/6. EMBO J. 1996;15:7026–7035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis RJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:7337–7342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossler MR, Yao H, York RD, Pan M-G, Rim CS, Stork PJS. cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell. 1997;89:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace LA, Sluis-Cremer N, Dirr HW. Equilibrium and kinetic unfolding of dimeric human glutathione transferase A1-1. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5320–5328. doi: 10.1021/bi972936z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Diener K, Jannuzzi D, Trollinger D, Tan T, Lichenstein H, Zukowski M, Yao Z. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel protein kinase with a catalytic domain homologous to mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31607–31611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteway MS, Wu C, Leeuw T, Clark K, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Thomas DY, Leberer E. Association of the yeast pheromone response G beta gamma protein subunits with the MAP kinase scaffold Ste5p. Science. 1995;269:1572–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.7667635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Jacinto E, Karin M. Molecular cloning and characterization of human JNKK2, a novel Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK)-specific kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7407–7416. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Cobb MH. MEKK1 binds directly to the c-Jun amino-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32056–32060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Robbins D, Christerson LB, English JM, Cobb MH. Cloning of rat MEK kinase 1 cDNA reveals an endogenous membrane-associated 195-kD protein with a large regulatory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:5291–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Shirakabe K, Shibuya H, Irie K, Oishi I, Oeno N, Taniguchi T, Nishida E, Matsumoto K. Identification of a member of the MAPKKK family as a potential mediator of TGF-beta signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:2008–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Dai T, Deak JC, Kyriakis JM, Zon LI, Woodgett JR, Templeton DJ. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase by MEKK1 phosphorylation of its activator SEK1. Nature. 1994;372:798–800. doi: 10.1038/372798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashar B, Irie K, Printen J, Stevenson BJ, Sprague GF, Jr, Matsumoto K, Errede B. Yeast MEK-dependent signal transduction: Response thresholds and parameters affecting fidelity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6556–6553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanke B, Rubie E, Winnett E, Chan J, Randall S, Parsons M, Boudreau K, McInnis M, Yan M, Templeton D, Woodgett J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are regulated through formation of specific kinase-activator complexes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29876–29881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]