Abstract

Using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, factors associated with incongruence between parents’ and adolescents’ reports of teens’ sexual experience were investigated, and the consequences of inaccurate parental knowledge for adolescents’ subsequent sexual behaviors were explored. Most parents of virgins accurately reported teens’ lack of experience, but most parents of teens who had had sex provided inaccurate reports. Binary logistic regression analyses showed that many adolescent-, parent-, and family-level factors predicted the accuracy of parents’ reports. Parents’ accurate knowledge of their teens’ sexual experience was not found to be consistently beneficial for teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes. Rather, parents’ expectations about teens’ sexual experience created a self-fulfilling prophecy, with teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes conforming to parents’ expectations. These findings suggest that research on parent–teen communication about sex needs to consider the expectations being expressed, as well as the information being exchanged.

A large body of literature has examined parent–teen communication about sex (for reviews, see Devore & Ginsburg, 2005; Miller, 2002). The degree of communication and its content may vary widely, and research suggests that the influence of such dialogue on adolescent sexual behavior is not necessarily uniform or consistent (Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003; Miller, 2002). Although many studies rely on survey questions that ask broadly about discussions between parents and teenagers, they focus primarily on the flow of information from parents to teens (e.g., DiClemente et al., 2001; Whitaker, Miller, May, & Levin, 1999). Less research has specifically examined the amount of information parents have about their teens’ behaviors. The limited extant research on this aspect of parent–teen communication about sex suggests that as with other behaviors parents may consider problematic (Barker, Bornstein, Putnick, Hendricks, & Suwalsky, 2007; Fisher et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2006), parents frequently have inaccurate knowledge of teenagers’ and young adults’ sexual experience (Bylund, Imes, & Baxter, 2005; Jaccard, Dittus, & Gordon, 1998; Yang et al., 2006). Furthermore, incongruence between parent and teen reports of adolescents’ sexual experience significantly affects teenagers’ subsequent sexual behaviors (Yang et al., 2006).

There are two possible types of incongruence between parents’ and teens’ reports of teens’ sexual experience. Parents are quite likely to underestimate their children’s sexual experience (i.e., teens report having had sex, whereas their parents report that the teen has not had sex; Yang et al., 2006). Overestimation (teens reporting not having had sex, whereas parents report the opposite), on the other hand, is relatively rare (Yang et al., 2006). Both of these types of incongruent reports tend to be “self-fulfilling prophecies” in which adolescents’ subsequent sexual behaviors frequently change to conform to the parent’s earlier report (Yang et al., 2006).

In this exploratory study, we ask two primary research questions. First, what factors are associated with incongruence in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of teens’ past sexual experience? We partition incongruence into parental overestimation and underestimation of teenagers’ sexual experience because past evidence suggests that these two types of discordant reports differ in important ways (Yang et al., 2006). It is likely to matter both that teenagers have actually had sex in the case of underestimation but not overestimation, and that parents think teens have had sex in the case of overestimation but not underestimation. Second, is accurate parental knowledge of teens’ sexual experience beneficial or problematic for adolescents’ subsequent sexual behaviors? We propose four alternative hypotheses about the predictors and consequences of incongruence between parents’ and teens’ reports.

Past evidence on congruence and incongruence in parents’ and teens’ reports of teens’ sexual activity has analyzed regional, nonrepresentative samples, has included a fairly limited set of potential correlates, and has not explored the consequences of incongruence for adolescents’ sexual behaviors beyond subsequent sexual intercourse. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), our study addresses these three areas, building on earlier work to provide a more comprehensive empirical picture of the correlates and consequences of incongruent reports about teens’ sexual activity. We also provide an exploratory theoretical framework for thinking about what might cause parents’ reports to be inaccurate and why that inaccuracy might matter.

We take the view that because engaging in sexual intercourse may not have negative consequences for all teens (for a discussion, see Bearman & Brückner, 2001), to fully understand the consequences of parental knowledge we should move beyond simply studying sex itself to analyzing whether adolescents are engaging in a range of healthier or riskier sexual behaviors (Bearman & Bruckner, 2001; for examples, see Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003; Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Jaccard & Dittus, 2000). We examine several behaviors that add dimensions of protection or risk to sexual activity, including consistent contraception, condom use, sex outside a romantic relationship, and having sex while under the influence of alcohol or other drugs. We also analyze two potential consequences of risky involvement in sex: teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). This broader view of sexual behaviors and consequences does not assume that all sex is bad for all teenagers, but rather quantifies specific risks and consequences.

Background and Hypotheses

Parent–Teen Communication About Sex

Evidence shows that parent–teen communication about sex can be difficult. Jaccard, Dittus, and Gordon (2000) found that many adolescents were concerned that their mothers would ask them personal questions, implying a desire to keep their mothers “in the dark” about their sexual experience. Similarly, many mothers expressed a wish to avoid “prying” into the teen’s sexual life. This implies a mutual aspiration among some parent–teen dyads to withhold accurate knowledge of the teen’s sexual behaviors from the parent. Despite such processes that may hinder the transfer of information from adolescent to parent, Jaccard et al. (1998) found that the more discussions the pair had about sex, the more likely congruent reports of teens’ sexual behavior were; Yang et al. (2006), conversely, found no such relationship.

The effect of parent–teen communication about sex or contraception on young people’s actual sexual behaviors is not always consistent (Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003; Fingerson, 2005; Miller, Benson, & Galbraith, 2001), but it has sometimes been found to be protective (DiClemente et al., 2001; DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999; Hutchinson, 2002; Hutchinson, Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2003). Furthermore, parent–teen communication may mitigate peer influences (Fasula & Miller, 2006; Whitaker & Miller, 2000) and strengthen the dampening effect of maternal disapproval on sexual behavior (Jaccard & Dittus, 1991). Parents’ comfort and skill in discussions influences the relationship between communication and sexual behaviors (Whitaker et al., 1999). Among boys in particular, feeling self-efficacious in communicating about sex with parents is associated with condom use (Halpern-Felsher, Kropp, Boyer, Tschann, & Ellen, 2004). These findings suggest that it is worthwhile to study the relationship between bidirectional parent–teen communication and adolescents’ sexual outcomes.

Of course, a parent and a teen making the same report about the teen’s sexual experience does not necessarily mean that the reports are always based on accurate two-way communication. Many parents may be making uninformed guesses about their teens’ experience. Rather than being random speculation, however, parents’ guesses are likely biased by their own characteristics and especially those of the teen. We anticipate that adolescent characteristics that are stereotypically associated with sexual activity affect the congruence of parents’ and teen’s reports. When teenagers belong to social categories that are associated with a greater likelihood of being sexually active, such as being older, being male, or being in an established romantic relationship (Halpern, Joyner, Udry, & Suchindran et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2006), we expect many parents to assume that their teens are sexually experienced. Conversely, parents may assume that younger, female, or single adolescents are not sexually experienced. Parents may use these assumptions to fill in gaps in their actual knowledge of teens’ behaviors, or even trust these assumptions more than what their teenagers are telling them.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

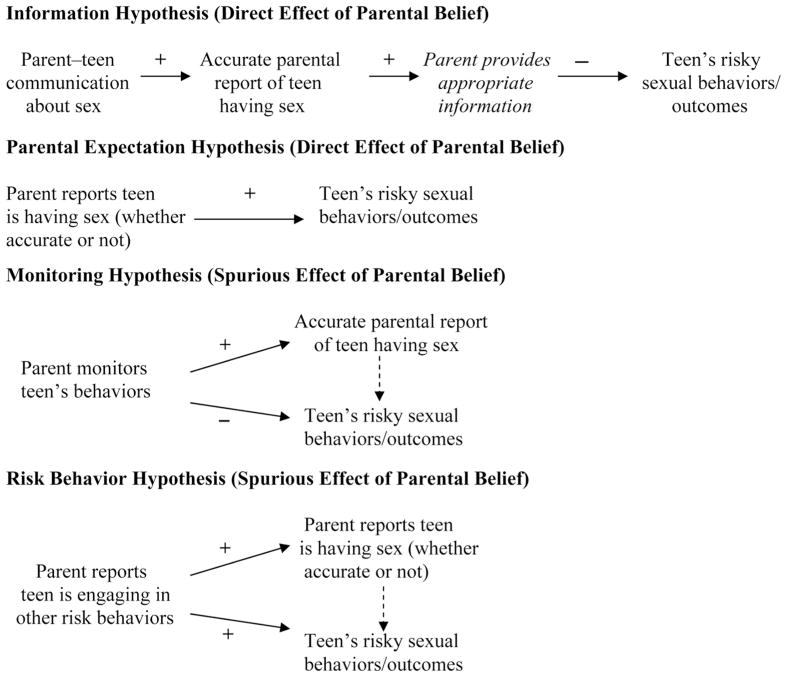

As we discussed earlier, our study has two main research questions. First, what factors are associated with incongruence in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of teens’ past sexual experience? Second, is accurate parental knowledge of teens’ sexual experience beneficial or problematic for subsequent sexual behaviors? We lay out four alternative exploratory hypotheses about the correlates of incongruence between parents’ and teenagers’ reports of teens’ sexual experience and the consequences of this incongruence for teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes. See Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of each hypothesis. Our two primary hypotheses assume a direct relationship between parents’ beliefs about whether their teens are sexually active and teens’ sexual outcomes, and two other hypotheses articulate a spurious relationship between parents’ reports and teens’ behaviors. We discuss the two primary hypotheses first.

Figure 1.

Graphical representations of hypotheses. Note. Italicized concepts are not measurable in the data; all others are measured. A dashed line indicates a relationship that is present when the third variable is excluded, and absent when it is included.

As Figure 1 shows, the information hypothesis assumes that parents’ accurate knowledge of their teens’ sexual experiences is beneficial for adolescents’ outcomes. The hypothesis first states that when parents and teens communicate more about sex, parents are more likely to accurately report their teens’ level of sexual experience, an idea that was supported by Jaccard et al. (1998). In turn, parents who have accurate knowledge of their teenage children’s sexual experiences may be able to provide situationally appropriate information and advice to minimize sexual risks and negative future consequences. Jaccard et al. (1998) wrote that when “parents anticipate [that] their children will become sexually active,” they “can ensure that teens are well informed about the consequences of an unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and strategies for practicing either abstinence or ‘safer’ sex” (p. 248). For example, Raffaelli, Bogenschneider, and Flood (1998) found that mothers who believed that their teenage child was sexually active were more likely to have discussed contraception with the teen. In the opposite situation, Bylund et al. (2005) wrote, parents not knowing about their children’s sexual activities “may inhibit parent–student conversations about … risky health behavior, ultimately putting the student at greater health risk” (p. 31). Therefore, we hypothesize that, although accurate parental knowledge may not change teens’ likelihood of having sex in the future, it may help them avoid problematic sexual behaviors and outcomes.

The second hypothesis is the parental expectation hypothesis (see Figure 1). Unlike with the first hypothesis, it is not the accuracy of the parent’s report that matters for teens’ outcomes, but rather whether the parent thinks the teenager has had sex. In some cases this parent report will be accurate, and in others it will not. This hypothesis states that parents’ expectations about whether their teens have had sex will affect teens’ subsequent sexual behaviors. If parents believe that their teenagers are not having sex, then teenagers will be motivated to live up to these expectations by abstaining from or minimizing future sex and risky sexual experiences.

A large social psychological literature on what is called “self-fulfilling prophecies” (Merton, 1948), “interpersonal expectancy effects” (Harris & Rosenthal, 1985), or “behavioral confirmations” (Swann, 1987) has demonstrated that when another person’s behavioral expectation does not match up with an individual’s actual behavior, the individual will often change the behavior to bring it in line with the expectation (for a review, see Harris & Rosenthal, 1985). Even if an expectation has not been explicitly expressed to an individual, it can be communicated through verbal and nonverbal cues (Correll & Ridgeway, 2003). Although a wide variety of social roles and specific expectations have been studied in this literature, parental expectations may have a particularly potent influence on children’s behavior. For example, parents’ expectations of their children’s performance have been shown to be powerful in determining young people’s future academic achievement (Neuenschwander, Vida, Garrett, & Eccles, 2007). The parental expectation hypothesis does not specify any particular factors that affect parental reports.

The last two hypotheses anticipate a spurious relationship between parents’ reports and teens’ sexual outcomes. Rather than incongruent reports themselves influencing teens’ behavior, these hypotheses assume that some underlying, or confounding, factor influences both parents’ reports and teens’ sexual behaviors and accounts for the initial appearance of a relationship between parents’ reports and teens’ behaviors. For the presence of a confounding factor to be supported, we identify four conditions that must be met in analyses: The underlying factor must be related to parent reports in the expected way, the underlying factor must be related to teen sexual behaviors in the expected way, there must be an initial relationship between parent reports and teen behaviors before the underlying factor is included in the model, and this initial relationship must disappear when the underlying factor is included.

The first of these two hypotheses is the monitoring hypothesis (see Figure 1), which expects that parents who monitor their teenage children’s behavior to a greater degree should more accurately assess teens’ sexual experience while at the same time making it less likely that teens will engage in subsequent sex and risky sexual behaviors. The first part of the hypothesis suggests that parents who have more knowledge of and control over their teens’ everyday lives will better be able to gauge what experiences they have had (supported by Stattin & Kerr, 2000); indeed, some studies assume this relationship by operationalizing parental monitoring as the level of agreement between parents and teens when reporting teens’ activities and experiences (for a discussion, see Stattin & Kerr, 2000). The second part of the hypothesis has also been supported in past research, which has found parental monitoring to be related to decreased risk behaviors among teens (Stanton et al., 2002). Parental monitoring has been defined differently across studies; we use multiple measures, including how often a parent is home when the teen is home, family meals shared together, and parents making decisions about the teen’s life.

The final hypothesis, which also expects a spurious relationship between parental reports and teen behavior, is the risk behavior hypothesis (see Figure 1). It considers teens’ experiences with sex to be one of a constellation of risky behaviors that are linked together in parents’ and teens’ minds and in actuality. For example, Costa, Jessor, Donovan, and Fortenberry (1995) found that earlier initiation of sexual intercourse among White and Hispanic teens was associated with earlier involvement in delinquent behavior, drinking alcohol, and marijuana use. If parents believe that their teenage children are engaging in another risky behavior such as smoking or drinking alcohol, then the parents are hypothesized to be more likely to report that the teenagers are also having sex. Similarly, teens who engage in these other risky behaviors will be more likely to experience subsequent sex and risky sexual behaviors and outcomes. Here as in the parental expectation hypothesis, it is not the accuracy of the parent’s report that initially appears to matter for teens’ outcomes (before other risky behaviors are controlled, revealing the spurious relationship), but rather whether the parent thinks the teenager has had sex.

It is important to note that, although each hypothesis specifies a unique set of directional relationships, the hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive and may influence each other. Although we have separated them neatly to describe them, real life may well be messier. For example, parents believing that a teenager is engaging in a variety of risky behaviors and closely monitoring her may be overlapping and mutually reinforcing processes.

Method

Data

This study’s data source is the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a nationally representative survey of students begun in the mid-1990s (Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997). Investigators chose a sample of 80 U.S. high schools and 52 middle schools with an unequal probability of selection. More than two-thirds of selected schools took part in the study, and those who refused were replaced by schools from within the same community. Although several subpopulations of students were oversampled and dropouts were not interviewed, probability weights included with the data set allow researchers to accurately represent the national population of adolescents in grades 7 through 12. Data for this analysis come from the first two waves of the study. In Wave I, a subsample of students from each school and a primary parent or parent-like figure completed extensive in-home interviews in 1995. Both teen and parent interviews were conducted face to face, and sensitive questions were asked using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing. Students who were not in grade 12 at Wave I were re-interviewed about one year later in 1996. In approximately 94% of cases, the parent completing the interview was the mother, who may have more accurately reported the teen’s level of sexual experience because previous research has found that teenagers are more likely to talk about sex with mothers than fathers (DiIorio et al., 1999; Raffaelli et al., 1998). Student response rates were 79% for Wave I and 88% for Wave II, and approximately 85% had a parent complete the survey in Wave I.

There were 11,369 eligible cases for analyses predicting incongruence (student interviewed at both waves, parent interviewed at Wave I, and not missing data for weight, clustering, or stratification variables), 4,054 eligible cases for risky sexual outcomes and behaviors (restricted to respondents who had sex by Wave II), and 2,018 eligible sexually active girls for the analysis of pregnancy. The number of cases included in our analyses (reported in each table) was further limited to those persons with information on covariates included in the analysis; for descriptive analyses, N =10,344. Supplemental analysis showed that listwise deleted cases were randomly distributed across categories of underestimation, sex while using drugs, sex outside a relationship, STIs, and pregnancies, but listwise deleted cases were overrepresented among those who had sex between Waves I and II (p <.001) and, importantly, among those in the overestimation category (p <.05).

Sometimes we included an indicator variable identifying cases with missing data for a particular variable instead of listwise deleting those cases to retain the other information reported by those respondents. These indicators were only included when a substantial proportion of the data for a variable was missing and when the missing indicator was not very collinear with other missing data indicators. Results of a sensitivity analysis comparing the models used in our analysis to models that excluded all missing data indicators except for grade point average (for which the missing category included many valid responses, such as a school not giving traditional grades) and listwise deleted all other missing cases are reported later.

Measures

This study’s main measure captures congruence and incongruence between teens’ self-reports and parents’ reports of teens’ experience with sexual intercourse. Two measures were used to create this variable. Teenagers reported whether they had engaged in “sexual intercourse” (further defined as when “a male inserts his penis into a female’s vagina”), and parents answered the question, “Do you think that he/she [the parent’s teenage child] has ever had sexual intercourse?”1 Our study assumed that the teen’s report of past sexual intercourse was accurate and judged the correctness of parental reports based on the teen’s report. We coded each possible combination of these two dichotomous variables to form four categories: yes–yes congruence, in which both teen and parent report that the teen has had sexual intercourse; no–no congruence, in which both report that the teen has not engaged in sexual intercourse; overestimation, in which parents report that their teen has had sex and the teen reports not; and underestimation, in which parents report that their teen has not had sex and the teen reports the opposite. Although just 2.4% of parents overestimated their child’s sexual experience, the 173 cases in this category made it sufficiently sized for exploratory multivariate analysis.

All other measures are described in Table 1, including information about waves, source variables, and response options. The measures that tested our study’s hypotheses are listed first, followed by teen-level and parent-level control variables, then teens’ sexual behaviors and outcomes. For these latter measures, the number of teens experiencing each outcome was included. We chose control variables from the teen and the parent levels because both were potentially important for understanding the dyad-level construct of incongruent reports. Our controls included demographic and socioeconomic variables, attendance at religious services, and reports of parent–teen relationship quality, because these or related variables have been shown to influence teen sexual behaviors or congruence in teen and parent reports of these behaviors (Bearman & Bruckner, 2001; Jaccard et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Variable Descriptions and Source Information

| Variable | Wave | Measurement | Source questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized variables | |||

| Information hypothesis | |||

| Parent gave contraception advice | I | Continuous | You have recommended a specific method of birth control to respondent. (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) |

| Parent communication about sex | I | Continuous | How much have you and [teen] talked about his/her having sexual intercourse and the negative things that would happen if he got someone/she got pregnant; the dangers of getting a sexually transmitted disease? How much have you talked to [teen] about birth control; about sex? |

| Monitoring hypothesis | |||

| Parental control over decisions | I | Continuous | Do your parents let you make decisions about the time you must be home on weekend nights, the people you hang around with, what you wear, how much television you watch, what time you go to bed on week nights, what you eat? |

| Parent’s presence in the home | I | Continuous | How often is your (mother/father) home when you leave for school; How often is your (mother/father) at home when you return from school; How often is your (mother/father) at home when you go to bed? (always to never) |

| Family meals shared | I | Continuous | On how many of the past 7 days was at least one of your parents in the room with you while you ate your evening meal? |

| Risky behavior hypothesis | |||

| Parent thinks teen smokes | I | Polytomous | Does your teen use tobacco regularly, that is, once a week or more? (Yes, no, don’t know) |

| Parent thinks teen drinks | I | Polytomous | Does your teen drink alcohol once a month? (Yes, no, don’t know) |

| Teen-Level Independent Variables | |||

| Teen age (years) | I | Continuous | What is your month and year of birth? |

| Teen gender (female) | I | Continuous | Respondent is male or female |

| Race/ethnicity | I | Polytomous | Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin? What is your race? If multiple: what is your primary race? |

| Teen satisfaction with parent relationship | I | Continuous | Overall, are you satisfied with your relationship with your mother/father? (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) |

| Church attendance | I | Polytomous | In the past 12 months, how often did you attend religious services? |

| Parent-level independent variables | |||

| Parent age | I | Continuous | How old are you? |

| Parent employment | I | Polytomous | Do you work outside the home? Are you employed full time? |

| Parent education (years) | I | Continuous | How far did you/your current spouse/partner go in school? Both parents averaged if available, otherwise one. If missing, used student report. |

| Parent religious attendance | I | Polytomous | How often have you gone to religious services in the past year? |

| Parental satisfaction with teen relationship | I | Continuous | Overall, you are satisfied with your relationship with respondent. (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) |

| Dependent variables | |||

| Had sex between Waves I and II | II | Dichotomous | In what month and year did you most recently have sexual intercourse (insert penis into vagina)? (n =4,213) |

| Recently had sex while using drugs | II | Dichotomous | The most recent time you had sexual intercourse, had you been using drugs? (n =346) |

| Sex outside a relationship | II | Dichotomous | Not counting the people you have described as romantic relationships, since month of last interview, have you had a sexual relationship with anyone? (n =1,187) |

| STI diagnosis between Waves I and II | II | Dichotomous | Since month of last interview, have you ever been told by a doctor or a nurse that you had chlamydia, syphilis, gonorrhea, HIV or AIDS, genital herpes, genital wars, trichomoniasis, or hepatitis B? If female, add bacterial vaginosis and non-gonococcal vaginitis. (n =231) |

| Pregnancy between Waves I and II | II | Dichotomous | [Girls only] Have you ever been pregnant? If so, what month and year? (n =141) |

| Condom use | II | Dichotomous | Thinking of all the times you have had sexual intercourse since month of the last interview about what proportion of the time [have you/has a partner of yours] used a condom? (Some of the time, half of the time, most of the time, all of the time) (n =2,889) |

| Recently had sex while drinking | II | Dichotomous | The most recent time you had sexual intercourse, had you been drinking? (n =217) |

Results

This section first reports the prevalence of incongruent reports of teens’ sexual experience. Results of multivariate analyses of first predictors of incongruence, then consequences of incongruence, are organized by hypothesis. All analyses used probability weights and adjusted for clustering and stratification.2

Prevalence of Incongruence

Table 2 reports weighted means and bivariate design-based F tests comparing congruent to incongruent parent reports within each category of teens’ Wave I sexual experience. In other words, among adolescents who had not had sexual intercourse by Wave I, teen–parent dyads in which parents confirmed this lack of experience were compared to those in which parents overestimated teens’ sexual experience. Similarly, among teenagers who had sexual intercourse by Wave I, teen–parent dyads in which parents corroborated this experience were compared to those in which parents underestimated teens’ sexual experience. We considered it necessary to split the models because if the four categories of congruence and incongruence were included together in the same model, they would have conflated the effects of teens’ Wave I sexual experience and parental reports.

Table 2.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics and Means Comparisons

| Variable | Range | Total Population N =10,344 (100%) |

Means

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No sex at Wave I

|

Sex at Wave I

|

|||||

| No–No N =7,055 (97.60%) |

Overestimate N =l73 (2.40%) |

Yes–Yes N =l,414 (45.38%) |

Underestimate N =1,702 (54.62%) |

|||

| Hypothesized variables | ||||||

| Information | ||||||

| Parent communication about sex | 1–4 | 3.17 | 2.80*** | 3.52 | 3.40*** | 3.04 |

| Parental contraception advice | 1–5 | 3.22 | 2.97*** | 3.52 | 3.80** | 2.95 |

| Parental monitoring | ||||||

| Prental control over decisions | 0–8 | 0.77 | 0.73* | 0.79 | 0.80*** | 0.76 |

| Family meals shared | 0–7 | 4.19 | 4.87** | 3.74 | 3.75*** | 4.29 |

| Parent in-home presence | 1.67–6 | 4.68 | 4.67 | 4.80 | 4.72 | 4.68 |

| Risky behaviors | ||||||

| Parent report of teen’s smoking | ||||||

| Thinks smokes | 0 or 1 | 0.09 | 0.03*** | 0.33 | 0.35*** | 0.12 |

| Does not think smokes. | 0 or 1 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.84 |

| Does not know | 0 or 1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Parent report of teen’s drinking | ||||||

| Thinks drinks | 0 or 1 | 0.03 | 0.01*** | 0.10 | 0.15*** | 0.03 |

| Does not think drinks | 0 or 1 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.72*** | 0.90 |

| Does not know | 0 or 1 | 0.04 | 0.01*** | 0.10 | 0.13*** | 0.07 |

| Teen-level independent variables | ||||||

| Age (years) | 11.42–21.17 | 16.23 | 15.60*** | 16.73 | 16.76*** | 16.06 |

| Teen is female | 0 or 1 | 0.50 | 0.57*** | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0 or 1 | 0.70 | 0.74* | 0.63 | 0.69* | 0.62 |

| Hispanic | 0 or 1 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0 or 1 | 0.13 | 0.10* | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0 or 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Other race | 0 or 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Two biological parents | 0 or 1 | 0.57 | 0.63*** | 0.27 | 0.34*** | 0.52 |

| Single parent | 0 or 1 | 0.23 | 0.20*** | 0.44 | 0.34** | 0.26 |

| Other two parent | 0 or 1 | 0.18 | 0.15** | 0.27 | 0.27*** | 0.18 |

| Other family | 0 or 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| In a romantic relationship | 0 or 1 | 0.30 | 0.20*** | 0.50 | 0.58*** | 0.48 |

| Grade point average | ||||||

| 0 to 1.9 | 0 or 1 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| 2 to 2.99 | 0 or 1 | 0.29 | 0.27** | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| 3 to 3.49 | 0 or 1 | 0.22 | 0.23* | 0.15 | 0.18* | 0.22 |

| 3.5 to 4 | 0 or 1 | 0.27 | 0.33*** | 0.13 | 0.12* | 0.16 |

| Missing | 0 or 1 | 0.17 | 0.14** | 0.25 | 0.28* | 0.22 |

| Satisfaction with parent relationship | 1–5 | 4.19 | 4.23 | 4.27 | 4.18 | 4.17 |

| Religious attendance | ||||||

| None | 0 or 1 | 0.24 | 0.21** | 0.34 | 0.36*** | 0.25 |

| <Once a month | 0 or 1 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.25*** | 0.19 |

| ≥Once a month, <once a week | 0 or 1 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| Once a week or more | 0 or 1 | 0.39 | 0.44** | 0.26 | 0.19*** | 0.33 |

| Missing | 0 or 1 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Parent-level independent variables | ||||||

| Age (years) | 20–86 | 41.01 | 40.96 | 40.37 | 41.00 | 40.37 |

| Parent employment | ||||||

| Full time | 0 or 1 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

| Part time | 0 or 1 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Unemployed | 0 or 1 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Missing | 0 or 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Parent education (years) | 0–18 | 12.83 | 12.06 | 12.59 | 13.41*** | 12.49 |

| Parent religious attendance | ||||||

| None | 0 or 1 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.29*** | 0.22 |

| <Once a Month | 0 or 1 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.32*** | 0.23 |

| >Once a Month, <once a week | 0 or 1 | 0.18 | 0.18* | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Once a week or more | 0 or 1 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.22*** | 0.35 |

| Missing | 0 or 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Parental satisfaction with teen relationship | 1–5 | 4.22 | 4.28 | 4.00 | 4.11* | 4.23 |

| Dependent Variables | ||||||

| Had sex between Waves I and II | 0 or 1 | 0.33 | 0.15*** | 0.59 | 0.82*** | 0.73 |

| Condom use | 0 or 1 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| Contraceptive use | 1–5 | 3.80 | 3.79 | 3.84 | 3.78 | 3.89 |

| Recently had sex while drinking | 0 or 1 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Recently had sex while using drugs | 0 or 1 | 0.03 | 0.01* | 0.03 | 0.09*** | 0.05 |

| Sex outside a relationship | 0 or 1 | 0.15 | 0.08*** | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| STI diagnosis | 0 or 1 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08** | 0.04 |

| Pregnancy | 0 or 1 | 0.01 | 0.01*** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

Note. Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995–1996; Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997).

Weighted means account for sample design effects (stratification and clustering).

The difference in accuracy of parental reports by level of Wave I sexual experience is significant (p <.001).

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001, design-based F test, within-row comparisons.

Eighteen percent of parents reported that their teens had a level of sexual experience that was different from the adolescent’s report (see Ns in Table 2 column headings). This incongruence was unevenly distributed depending on the teen’s sexual experience (p <.001 in a supplemental design-based F test). Parents overwhelmingly had accurate knowledge among teenagers who had not had sexual intercourse, with 98% congruent reports. Among sexually experienced teens, however, 55% of parents reported inaccurately that their children had not had sex. Just 1% of parents answered that they did not know whether their teen had had sex; these cases were deleted from analysis because there were too few to form a separate category. This low percentage suggests that unless levels of honest parent–teen communication about sex were extraordinarily high in this sample, many parents were probably guessing about their teens’ sexual experience.

Predictors of Incongruence

Our first research question asks what factors are associated with incongruence in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of teens’ past sexual experience. With the exception of teen reports of parent–teen relationship quality and parents’ employment status, at least one category of each of the selected correlates was significantly associated with parental over- or underestimation of teens’ sexual experience in Table 2. Rather than discussing specific bivariate relationships, we turn to the multivariate logistic regression models reported in Table 3 that combined all of these potential predictors. The models used the same comparison of overestimation to no–no congruence and underestimation to yes–yes congruence. As we expected, when teens belonged to social categories that parents probably associated with being sexually active, their parents were often more likely to report that the adolescents have had sex. Parents were more likely to report that older teens and teens who were in a romantic relationship had had sex in both models, and parents were more likely to report for male teens than for females that the teens had had sex when they actually had not.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression, Analyses of Incongruent Reports of Sexual Experience

| Sexually Inexperienced Teens, Parental Overestimation Compared to Accurate Knowledge

|

Sexually Experienced Teens, Parental Underestimation Compared to Accurate Knowledge

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Information hypothesis | ||||

| Parent contraception advice | 0.17* | .08 | −0.34*** | .04 |

| Parent communication about sex | 0.33* | .16 | −0.49*** | .09 |

| Monitoring hypothesis | ||||

| Parental control over decisions | 0.71 | .42 | 0.04 | .27 |

| Family meals shared | −0.06 | .04 | 0.05* | .02 |

| Parent in-home presence | 0.15 | .12 | −0.18 | .10 |

| Risky behavior hypothesis | ||||

| Parent thinks teen drinks | 0.55 | .50 | −1.08*** | .25 |

| Parent does not know | 1.19* | .47 | −0.61** | .19 |

| Parent thinks teen smokes | 1.78*** | .33 | −0.86*** | .15 |

| Parent does not know | 1.09 | .76 | −0.44 | .31 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Teen age (years) | 0.52*** | .08 | −0.42*** | .05 |

| Teen is female | −0.88*** | .25 | 0.06 | .13 |

| Race/ethnicity (White) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.71* | .34 | 0 | .15 |

| Hispanic | 0.35 | .33 | 0.15 | .19 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | −0.08 | .6 | 0.53 | .42 |

| Other race | 0.26 | .46 | 0.07 | .34 |

| Parent age (years) | −0.02 | .02 | 0.03** | .01 |

| Family structure (2 biological parents) | ||||

| Other two parent | 1.06*** | .29 | −0.68*** | .13 |

| Single parent | 1.34*** | .3 | −0.47** | .16 |

| Other family structure | 0.89 | .63 | −0.93** | .32 |

| Parent employment (not working) | ||||

| Full-time | 0.08 | .27 | −0.03 | .14 |

| Part-time | −0.33 | .36 | 0.12 | .18 |

| Missing | 0.74 | .61 | −0.32 | .52 |

| Parent education (years) | −0.09 | .06 | 0.08*** | .02 |

| Parent religious attendance (≥1/week) | ||||

| No attendance | −0.07 | .34 | −0.43** | .15 |

| <Once a month | −0.21 | .28 | −0.59*** | .14 |

| ≥1/month, <1/week | −0.64 | .33 | −0.2 | .16 |

| Missing | 0.39 | .89 | ||

| Teen in a romantic relationship | 1.26*** | .22 | −0.42*** | .11 |

| Teen grade point average (≥3.5) | ||||

| 0 to 1.9 | −0.1 | .71 | 0.09 | .29 |

| 2 to 2.9 | 0.44 | .37 | −0.09 | .19 |

| 3 to 3.49 | −0.17 | .41 | 0.05 | .19 |

| Missing | 0.29 | .47 | −0.02 | .2 |

| Parent satisfaction with parent-teen relationship | −0.26 | .14 | 0.17** | .06 |

| Constant | −12.53** | (1.88) | 8.67** | (.1) |

| N =7228 | N =3116 | |||

Note. Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995–1996; Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997). Analyses account for sample design effects (weighting, stratification, and clustering).

n =7,228.

n =3,116.

The examination of the predictors of accurate parental knowledge reported in Table 3 tested part of each of the hypotheses depicted in Figure 1 except the parental expectation hypothesis. The positive relationship between parent–teen communication and accurate parental reports of teens’ sexual experience that we expected based on the information hypothesis was not confirmed. When parents communicated more with their teen about sex and when they gave the teen advice about contraception, they were not consistently more accurate in their reports of the teen’s sexual experience. Instead, in these cases parents were consistently more likely to report that the teen had had sex, whether or not this was accurate.

The monitoring hypothesis, which expected parental monitoring to increase the accuracy of parents’ reports of teens’ sexual experience, was largely not supported in Table 3 either. Only one relationship between the three measures of parental monitoring and over- or underestimation was significant, and it was in the opposite direction from the predictions made by the hypothesis. This was the positive association between the number of family meals shared and parental underestimation of teens’ sexual experience.

Analyses reported in Table 3 mostly supported the risk behavior hypothesis, which expected parents’ reports that teens are engaging in other risk behaviors to increase the likelihood of parents reporting that the teen has had sex (whether accurate or not). Although the relationship between parents thinking that their teens drank alcohol and overestimation was not significant, all of the others were significant in the expected direction. Parents who thought their teens drank or smoked were less likely to underestimate teens’ sexual experience, and parents who thought their teens smoked were also more likely to overestimate. In other words, these parents thought their teen had had sex in both models.

Several other significant relationships in Table 3 are worth mentioning. Two other factors were related to parental reports of teens’ sexual experience across both categories of teens’ actual sexual experience. Single-parent and other two-parent family structures were positively associated with parents believing their teens had had sex in both models, compared to two biological parent family structures. Parents’ overestimation of adolescents’ sexual experience was more likely for African American than for White teens. Four characteristics of the parents were positively related to their underestimation of their teenage children’s sexual experience but not their overestimation: being older, attending religious services more frequently, being more highly educated, and being more satisfied with the parent–teen relationship. The first two of these factors in particular may be related to parents perceiving social norms that discourage teenage sex, which could influence their own expectations about whether their teenage child has past sexual experience in the absence of concrete evidence to the contrary.

It is interesting that none of the variables in the models reported in Table 3 consistently predicted the accuracy of parents’ reports of teens’ sexual experience across both models. Rather, the variables that were significant in both models were consistent in a different way: They predicted parents’ beliefs about whether the teen had had sex (which, by definition, would have been an accurate report in one model, but not the other). If any of these predictors had improved the information that teens were providing to parents about their sexual experiences, then we would have expected them to be consistently related to accuracy. The lack of such consistent accuracy suggests that on average, expectations, assumptions, and attitudes had a greater influence on parents’ reports of their teens’ sexual experience than honest information received from the adolescent.

Consequences of Incongruence

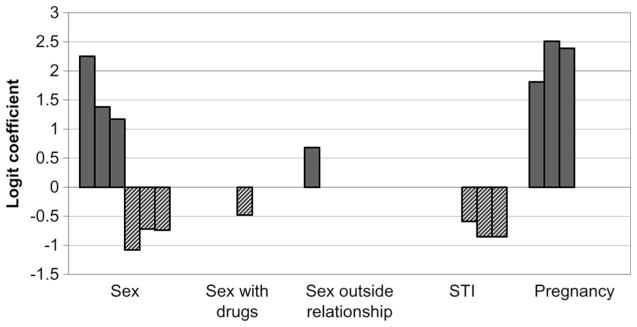

Our second research question asks how incongruence between teens’ sexual activity and parental reports influences adolescents’ subsequent sexual behaviors. Guided by our perspective that sexual activity can be conducted in healthier or riskier ways, we chose a series of sex-related adolescent outcomes, reported in bivariate analyses in Table 2 and multivariate analyses in Figure 2 and Table 4. Each outcome was measured during the one-year interval between Waves I and II of the survey. Multivariate models included most of the variables from Table 2 as controls and again split teens by their Wave I sexual experience. We first analyzed subsequent sexual intercourse, replicating part of Yang et al.’s (2006) analysis on a larger, nationally representative sample with a wider variety of covariates. Second, we expanded on past research by analyzing five measures of protective or risky sexual practices for a subsample of teens who had sex between Waves I and II: condom use, general contraceptive use, sex while drinking alcohol, sex while using drugs, and sex outside an established romantic relationship. Third, we analyzed two problematic sexual health outcomes for teens who had sex between Waves I and II: STI diagnosis and (for girls only) pregnancy. These outcomes were relatively rare, but Table 1 reports that there were enough cases (155 STI diagnoses and 141 pregnancies) for exploratory multivariate analysis.

Figure 2.

Summary of logistic regression coefficients predicting effects of parents’ over- and underestimation on teens’ sexual behaviors. Note. Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995–1996; Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997). Logistic regression coefficients are drawn from Table 4; N varies. Only significant effects (p <.05) are included. Solid bars compare overestimation to accurate knowledge of no sexual experience at Wave I; striped bars compare underestimation to accurate knowledge of sexual experience at Wave I. The first bar in each group of three is from bivariate models, the second includes controls and parent–teen communication about sex, and the third includes parental monitoring and reports of teens’ non-sex-related risky behaviors. The two single bars are both from bivariate models. Analyses account for sample design effects (weighting, stratification, and clustering). STI =sexually transmitted infection.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Analyses of Teens’ Sexual Behaviors Between Waves

| Had Sex at Wave II

|

Recent Sex w/Drugs

|

Casual Sex

|

STI

|

Pregnancy

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Sex, W1 | Sex, W1 | No Sex, W1 | Sex, W1 | No Sex, W1 | Sex, W1 | No Sex, W1 | Sex, W1 | No Sex, W1 | Sex, W1 | |

| Incongruent reports | ||||||||||

| Overestimation | 1.17*** | −0.37 | 0.45 | −0.79 | 2.39** | |||||

| Underestimation | −0.74*** | −0.25 | 0.05 | −0.79** | −0.20 | |||||

| Information hypothesis | ||||||||||

| Parental contraception advice | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.32 | −0.09 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.18* | −0.07 | −0.04 |

| Communication about Sex | 0.18** | 0.21* | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.33 | 0.35* | −0.20 | 0.13 |

| Monitoring hypothesis | ||||||||||

| Parent control over decisions | 0.42* | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.31*** | 0.32 | −0.89 | −1.41* | −0.10 | −0.65 | 2.80*** |

| Family meals shared | −0.04* | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.23* | −0.05 |

| Parent in-home presence | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.26 | 0.06 | 0.28 | −0.22 |

| Risky behaviors hypothesis | ||||||||||

| Parent thinks teen drinks | 0.90** | −0.03 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.02 | −0.66 |

| Parent does not know | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.79 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.61 | ||

| Parent thinks teen smokes | 0.52** | −0.34 | 0.29 | 0.64** | 0.43 | 0.16 | −0.33 | −0.35 | 1.19 | 0.59 |

| Parent does not know | 0.71 | 0.60 | −0.35 | 1.19* | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.04 | −0.31 | 1.84* | 0.03 |

| Constant | −4.38*** | −3.61* | −0.16 | −0.65 | 0.99 | 2.67* | 1.75 | −0.77 | −5.27 | −0.15 |

Note. Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995–1996; Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997).

Coefficients, not odds ratios, are reported. Analyses account for sample design effects (weighting, stratification, and clustering). All dependent variables but the first are restricted to those who had sex between waves; the last is further restricted to females. Models control for teen age, gender, race or ethnicity, family structure, religious attendance, relationship status, grade point average, relationship with parent, and parent employment and education.

p <.05,

p <0.01,

p <.001; two-tailed tests.

Table 2 shows that not all of these outcomes were related to incongruent reports in bivariate tests. Neither over- nor underestimation was significantly related to subsequent condom use, broader contraceptive use, or having sex while drinking alcohol. Because incongruent reports were not associated with these outcomes, we did not present them in Table 4. Underestimation was not related to having subsequent sex outside a romantic relationship or pregnancy, and overestimation was not related to receiving an STI diagnosis.

All other relationships were statistically significant. For each of these associations, parents’ belief that their teen had had sex (i.e., overestimation in the first model and yes–yes congruence in the second) was positively related to subsequent sex and risky sexual behaviors and outcomes. In past analyses using nonrepresentative data, Yang et al. (2006) found a similar relationship between underestimation and subsequent sex, but they did not find a significant relationship for overestimation as we did. The findings reported here do not support the information and monitoring hypotheses, which expected the accuracy of parents’ reports, rather than their beliefs that their teens had or had not had sex, to drive these relationships. These findings do provide preliminary support for the risk behavior and expectations hypotheses, which predicted that parents’ beliefs that their teens had had sex, and not the accuracy of parent reports, would be related to teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes.

Figure 2 expresses these same relationships in terms of bivariate logistic regression coefficients in the first bar for each dependent variable. The second bar shows the coefficients when controls were added in multivariate logistic regression models. The third bar, which represents coefficients from the models reported in Table 4, included monitoring and non-sexual risky behaviors to test for confounding factors. In every case, only significant relationships at the p <.05 level were displayed in the figure. We discuss results pertaining to each hypothesis below.

The information hypothesis made no prediction about subsequent sex, but expected parent–teen communication about sex and contraception advice to reduce the likelihood of risky sexual behaviors and negative outcomes. Results reported in Table 4 did not support this hypothesis. The only relationship in the expected direction was that each one-unit increase in the five-point scale of parental contraception advice reduced the likelihood of receiving an STI diagnosis by 16% among teens who had had sex by Wave I.3 The only other significant relationships between communication/advice and outcomes were not in the expected direction: Parent–teen communication about sex by Wave I increased the odds of subsequently having sex both for teens who had and those who had not had sex.

The monitoring hypothesis expected parental monitoring of teens to reduce the likelihood of subsequent sex and risky sexual behaviors and outcomes. Most of the findings reported in Table 4 did not support the hypothesis. The few relationships between monitoring measures and teen outcomes that were significant were inconsistent in their direction, and more of them contradicted than supported the hypothesis. On the one hand, eating more meals together reduced the likelihood of first sex among virgins at Wave I, and more parent decisions about the teen’s life reduced the likelihood of receiving an STI diagnosis among the same group; but on the other hand, eating more meals together increased the likelihood of pregnancy among Wave I virgins, and more parental decisions raised the odds of subsequently having sex among Wave I virgins and increased the likelihood of having sex while on drugs and getting pregnant among teens who were sexually experienced at Wave I. The rest of the hypothesized relationships were not significant.

The risk behavior hypothesis received some support in the direction expected by the hypothesis, but only three of the 20 hypothesized relationships were significant. Parents’ reports that they believed their teen drank alcohol (as opposed to thinking that they did not) were associated with a 146% increase in the likelihood of subsequently having sex among Wave I virgins, whereas believing that their teen smoked increased the likelihood of having sex by 68% among the same group. Parent reports of believing their teen smoked cigarettes were associated with a 90% increase in the risk of reporting having sex while using drugs among teens that were sexually experienced at Wave I. For all other models, however, neither of the risk behavior variables were significant, providing only weak empirical support for that part of the hypothesis. We tested another part of the hypothesis by introducing risk behavior measures into the multivariate model. Including these measures did not substantially reduce the effect of parental over- or underestimation on any teen sexual outcome. This can be seen by comparing the second and third bars for each outcome in Figure 2. This lack of reduction in the effect of incongruent reports on sexual outcomes does not provide support for the risk behavior hypothesis.

Like the risk behavior hypothesis, the parental expectation hypothesis anticipates that parents’ reports of the teen having sex, rather than accurate reports, will be related to teens’ sexual outcomes. Because the effect of parents’ beliefs about teens’ sexual experience is assumed to be direct, the hypothesis anticipates that other factors will not reduce the effect of parental reports on sexual outcomes. Figure 2 shows that regardless of the model being presented, every significant relationship was in the direction predicted by the parental expectation hypothesis. Figure 2 and Table 4 report coefficients from models that controlled for parent–teen communication, monitoring, and risk behaviors. Four of the 10 relationships between incongruent reports and teen outcomes were still significant in the direction predicted by the parental expectation hypothesis, providing some support for this hypothesis. In these models, parents’ reports that teens had had sex increased the likelihood of subsequently having sex by 222% for previously inexperienced teens and by 52% for previously experienced teens, parental underestimation of teens’ sexual experience cut the odds of receiving an STI diagnosis by more than half, and parental overestimation raised the odds of girls getting pregnant more than tenfold.4 This means that when parents believed their teens had had sex, the teens were more likely subsequently to have sex and have negative sex-related outcomes. Furthermore, when parents believed their teens had not had sex, the teens were less likely to engage in sex, and those who did were less likely to report an STI diagnosis.

Discussion

Using nationally representative data from the Add Health survey, we found that the overwhelming majority of parents of teens who had not had vaginal intercourse accurately reported the adolescents’ lack of experience. In contrast, more than one half of parents whose children had had intercourse inaccurately reported that the adolescent had not had sex. The finding that parents more often had accurate knowledge of their teenage children’s sexual experience when they were virgins suggests that parents’ awareness of their children’s sexual activity was influenced by societal norms or personally held attitudes against teenage sex. This could occur either through social desirability bias in the information teens provided to parents, or through parents’ assumption that their children would conform to their own and society’s expectations, which may have influenced the information they sought and the ways in which they perceived this information.

A wide variety of adolescent-, parent-, and family-level factors were involved in predicting parents’ knowledge of teenagers’ sexual experience. The results suggest that parents’ objective estimation of their children’s sexual experience was not solely based on actual knowledge, but rather was influenced both by their own characteristics and by a probabilistic assessment of the kinds of adolescents who are likely to have sex. Some of the significant findings confirmed past evidence on the predictors of congruence. For example, Jaccard et al. (1998) found that teens’ and parents’ ages, parents’ satisfaction with their relationship with the teen, and parent–teen communication about sex were related to parental underestimation in the same direction as in Table 3, and Yang et al. (2006) found that teens’ age was positively related to parental overestimation. Other significant findings were not replicated in other studies: In Yang et al., teen gender was not significantly related to overestimation of teens’ sexual experience, and teen age and parent attendance at religious services were not associated with underestimation. Some of our predictors had not previously been included in these studies’ multivariate models of parental reports of teens’ sexual experience, such as teens’ race or ethnicity and involvement in a romantic relationship, family structure, and parents’ education levels and reports of teens’ experience with smoking and drinking.

We proposed several hypotheses about the relationship between incongruent parent and teen reports of teens’ sexual experience and teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes (see Figure 1). Although the hypotheses were treated as separate from each other and from the control variables, these processes are not necessarily mutually exclusive and may work in tandem. First, the information hypothesis expected parent–teen communication about sex to increase the accuracy of parents’ reports, which in turn would allow parents to provide appropriate information to the teen that would reduce their risky sexual outcomes. This hypothesis was not supported by the data: Parent–teen communication about sex made parents more likely to report that their teen was having sex, which was not necessarily accurate, and correct parental reports only decreased the likelihood of risky sexual outcomes when parents believed the teen had not had sex.

Second, the monitoring hypothesis expected parental monitoring of teens’ behaviors to account for the relationship between accurate parental reports and teens’ sexual outcomes. This hypothesis was not supported. Parental monitoring was positively related to accurate parental reports and negatively associated with teens’ risky sexual outcomes only rarely and inconsistently. Furthermore, accurate parental reports only reduced the odds of teens’ risky sexual outcomes when parents thought the teen had not had sex.

The third hypothesis, risk behavior, maintained that parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ involvement in other risky behaviors should account for the relationship between parents reporting that teens have had sex and teens’ sexual outcomes. This hypothesis received mixed support. Two findings supported this hypothesis: First, parental reports of teens’ experience with drinking and smoking were usually positively associated with parents believing that teens had had sex. Second, parent reports that teens had had sexual intercourse, rather than accurate parent reports, predicted subsequent sex and some risky sexual behaviors and outcomes. Two findings provided less support: Parents’ reports that they believed their teens had smoked or drank alcohol only occasionally predicted teens’ sexual outcomes, and introducing other risky behaviors and parental monitoring measures into Model 3 in Figure 2 did not substantially reduce the effect of over- or underestimation on any outcome.

We did find support for the parental expectation hypothesis, which stated that parents’ beliefs about their teenagers’ sexual experience would influence adolescents’ subsequent behaviors to confirm the parents’ expectations. First, parental reports that teens were sexually experienced, rather than accurate parental reports, predicted teens’ subsequent sexual outcomes. Second, the positive relationships between parent reports that their teens had had sex and teens’ subsequent sex and risky sexual outcomes frequently remained strong, even after accounting for parent–teen communication about sex and possible confounding factors (other risky behaviors and parental monitoring). None of the other hypotheses predicted this finding accurately.

Taken together, the findings suggest that parental expectations about teens’ sexual experience may have important effects on adolescents’ behaviors, and may frequently outweigh the potential benefits of advice and information that parents can convey if they are aware of teens’ sexual activity. Although the mechanism through which this occurs could not be documented empirically, we believe that these expectations affected teens’ subsequent sexual behaviors through the process of self-fulfilling prophecy. We know from experimental and field research that when someone else’s expectations about a person’s behavior do not square with the person’s actual behavior, that person will frequently modify the behavior to conform to the expectation (for a review, see Harris & Rosenthal, 1985). As we discussed earlier, this can occur even when the expectation has been communicated through indirect verbal and nonverbal cues (Correll & Ridgeway, 2003) rather than directly. It is important to note that some individuals in some situations will try to alter the other person’s expectation rather than their own behavior (Swann, 1987), but often it is the behavior that they work to change instead. Adolescents may be motivated to do this by the human impulse to conform to others’ expectations (Asch, 1956; Milgram, 1965). When those expectations are being communicated by a parent, teens may be motivated further by a desire to please the parent to maintain a good relationship and to keep parents from exercising the considerable structural power they have over minor teens. The finding that teens are changing their sexual activity, a relatively private behavior that their parents presumably do not observe, suggests that at least some adolescents have internalized the parents’ expectations and are not merely making an appearance of conformity.

It is less clear why the self-fulfilling prophecy extends beyond sexual intercourse, the precise behavior about which the parents have expectations, to other kinds of risky and protective sexual behaviors and outcomes. The teen outcomes that changed on the basis of parents’ expectations included sex outside a relationship, sex under the influence of drugs, STI diagnoses, and (for girls) pregnancy. At the same time, use of condoms and general contraceptives and sex under the influence of alcohol were not affected by parental beliefs about teens’ sexual experience. Future research should work to understand why the self-fulfilling prophecy extended to some sexual outcomes but not others.

Parents’ knowledge of their teenagers’ sexual experience is only sometimes beneficial: It is frequently problematic for teens’ sexual outcomes when parents believe that teens are having sex when they are not, but parents believing that teens have not had sex when they have is actually protective. Therefore, increasing the accuracy of parental knowledge of teens’ sexual activity may not be a panacea for improving adolescents’ sexual outcomes. Rather, clearly expressing an expectation that the teen is avoiding risky sexual behaviors may be a more promising route for parents that could lead to a positive self-fulfilling prophecy.

Our policy recommendations are only tentative because this study is exploratory, but the results imply that decoupling parent–teen communication about sex from an assumption that the teen is sexually active and communicating high parental expectations of the teen staying safe from sexual risk may be promising routes for policy. The former goal might be achieved through early discussions about sex and contraception, prior to an age when it is likely that the teen may be sexually active. If parents combined concrete information with a clearly expressed expectation that the teen will stay safe from sexual risk, then the latter goal might be attained as well. Future research should examine whether this type of communication is effective for reducing sexual risk.

This exploratory study has other limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, it is important to note that parents’ reports in the survey could not tell us whether they truly knew that their teenagers were or were not sexually active, or whether they were simply making a guess. It would be useful to know when parents are guessing and when they have actual knowledge of the adolescent’s sexual experience.5 The implications of congruent reports could be more positive for this latter group than what we found in this study. In particular, when teenagers have explicitly communicated to parents that they are sexually active, then parents may be able to provide information and support that could reduce sexual risk. Second, both mothers and fathers of teens should be included in future research because these processes may differ by parents’ gender and may interact with the teen’s gender. Third, social desirability bias may influence parents’ reports of teens’ sexual activity. Community norms discouraging adolescent sex may disproportionately influence some parents to report less sexual experience on the part of the teen to prove themselves as “good parents,” in which case it may be the norms themselves and not parents’ expectations that actually influence some adolescents’ sexual behaviors in our study.6 Measures of community norms would make it possible to disentangle the effects of community norms from those of parental expectations.

This study adds to our understanding of the factors that shape the information parents have about their teens’ risky behaviors, as well as the ways in which this information is directly or spuriously related to teens’ subsequent outcomes. We find that greater levels of parent–teen communication about sex do not lead to parents reporting more accurate information about adolescents’ sexual experience. Rather, parents who think their teen is having sex are communicating with the adolescent more about sex and providing advice about contraception, without gaining accurate knowledge from this communication. Our findings echo past research in suggesting that the process of parent–teen communication about sex is often complicated, opaque, and rife with assumptions and expectations that may sometimes be more important than the information being exchanged.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by Grant P01–HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin St., Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth/contract.html). We thank Richard Rogers and Jeff Dennis for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

It is unfortunate that the survey defined “sexual intercourse” more specifically for teens but not for parents. Furthermore, the survey’s definition of sexual intercourse excluded all homosexual acts, as well as anal and oral heterosexual acts that many people include in their definitions of sexual intercourse (Bogart, Cecil, Wagstaff, Pinkerton, & Abramson, 2000; Sanders & Reinisch, 1999). Add Health did not include questions about oral sex in either wave, and anal sex experience was only recorded at Wave II. Supplementary analyses using Wave II teen reports and Wave I parent reports (the only wave available) suggested that including both anal and vaginal sex provoked little change in levels of congruence between parent and teen reports compared to vaginal sex only.

We compared multivariate models presented in Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 2 with models using analysis samples that listwise deleted all missing cases instead of including missing data indicators on some variables. The only exception is that we still include a missing data indicator for grade point average (GPA) because that missing data indicator includes many valid cases in which students cannot report a GPA (e.g., if their school does not give traditional grades). For the main results testing hypotheses, the sign and significance does not differ across the two samples except that in the analysis of the effect of underestimation on the likelihood of having sex with drugs equivalent to Table 4, the effect of parents having control over decisions about the teens’ life was no longer significant, but had the same sign and similar magnitude.

Odds and percentages reported here and again later were calculated using odds ratios by exponentiating the logistic regression coefficients from Table 4 or Figure 2 and subtracting from 1 when applicable (in this case, e−0.2 =0.82 and 1 −0.82 =0.18).

Although this last result is statistically significant at the p <.01 level, it is based on 31 overestimating parents. Therefore, these results should be treated as preliminary.

Supplemental analyses not shown restructured the congruency categories such that if parents were wrong by more than one year when predicting the age at which their child first had sex, they were moved into the incongruent category. This restructuring did not change our findings, nor did it largely change the size of the categories.

Analyses not shown examined the effects of teens’ beliefs that their peers would respect them more if they had sex (a proxy for peers’ social norms) and of teens’ perception of peers’ familiarity with different contraception methods (a proxy for peers’ behavioral norms) and found that these variables did not alter the relationships between overestimation or underestimation and sexual outcomes.

References

- Asch SE. Studies of independence and conformity: A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs. 1956;70(9 Whole No 416) [Google Scholar]

- Barker ET, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hendricks C, Suwalsky JTD. Adolescent–mother agreement about adolescent problem behaviors: Direction and predictors of disagreement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:950–962. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Brückner H. Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:859–912. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Cecil H, Wagstaff DA, Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Is it “sex”? College students’ interpretations of sexual behavior terminology. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bylund CL, Imes RS, Baxter LA. Accuracy of parents’ perceptions of their college student children’s health and health risk behaviors. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:31–37. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.1.31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clawson CL, Reese-Weber M. The amount and timing of parent–adolescent sexual communication as predictors of late adolescent sexual risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:256–265. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll SJ, Ridgeway CL. Expectation states theory. In: Delamater J, editor. Handbook of social psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Donovan JE, Fortenberry JD. Early initiation of sexual intercourse: The influence of psychosocial unconventionality. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:93–121. [Google Scholar]

- DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2005;17:460–465. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000170514.27649.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies SL. Parent–adolescent communication and sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent females. Journal of Pediatrics. 2001;139:407–412. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasula AM, Miller KS. African-American and Hispanic adolescents’ intentions to delay first intercourse: Parental communication as a buffer for sexually active peers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerson L. Do mothers’ opinions matter in teens’ sexual activity? Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:947–974. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SL, Bucholz KK, Reich W, Fox L, Kuperman S, Kramer J, et al. Teenagers are right—Parents do not know much: An analysis of adolescent–parent agreement on reports of adolescent substance use, abuse, and dependence. Alcoholism—Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1699–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Joyner K, Udry JR, Suchindran C. Smart teens don’t have sex (or kiss much either) Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:213–225. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Kropp RY, Boyer CB, Tschann JM, Ellen JM. Adolescents’ self-efficacy to communicate about sex: Its role in condom attitudes, commitment, and use. Adolescence. 2004;39:443–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, Rosenthal R. Mediation of interpersonal expectancy effects: 31 meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shrier LA, Shahar G. Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological–transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:286–297. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK. The influence of sexual risk communication between parents and daughters on sexual risk behaviors. Family Relations. 2002;51:238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman P, Fong GT. The role of mother–daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus P. Parent–teen communication: Toward the prevention of unintended pregnancies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ. Adolescent perceptions of maternal approval of birth control and sexual risk behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1426–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon VV. Parent–adolescent congruency in reports of adolescent sexual behavior and in communications about sexual behavior. Child Development. 1998;69:247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon VV. Parent–teen communication about premarital sex: Factors associated with the extent of communication. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;15:187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Review. 1948;8:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram S. Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Human Relations. 1965;18:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC. Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:22–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Benson B, Galbraith KA. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001;21:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander MP, Vida M, Garrett VL, Eccles JS. Parent’ expectations and students’ achievement in two western nations. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(6):594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Bogenschneider K, Flood MF. Parent–teen communication about sexual topics. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19:315–333. doi: 10.1177/019251398019003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. Would you say you “had sex” if …? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:275–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Li X, Pack R, Cottrell L, Harris C, Burns JM. Longitudinal influence of perceptions of peer and parental factors on African American adolescent risk involvement. Journal of Urban Health. 2002;79:536–548. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB., Jr Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1038–1051. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Miller KS. Parent–adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: Impact on peer influences of sexual risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;15:251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, Levin ML. Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: The importance of parent–teenager discussions. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Stanton B, Cottrel L, Kaljee L, Galbraith J, Li X, et al. Parental awareness of adolescent risk involvement: Implications of overestimates and underestimates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]