Abstract

Objective To investigate whether the mortality gap has reduced in recent years between people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and the general population.

Design Record linkage study.

Setting English hospital episode statistics and death registration data for patients discharged 1999-2006.

Participants People discharged from inpatient care with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, followed for a year after discharge.

Main outcome measures Age standardised mortality ratios at each time, comparing the mortality in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with mortality in the general population. Poisson test of trend was used to investigate trend in ratios over time.

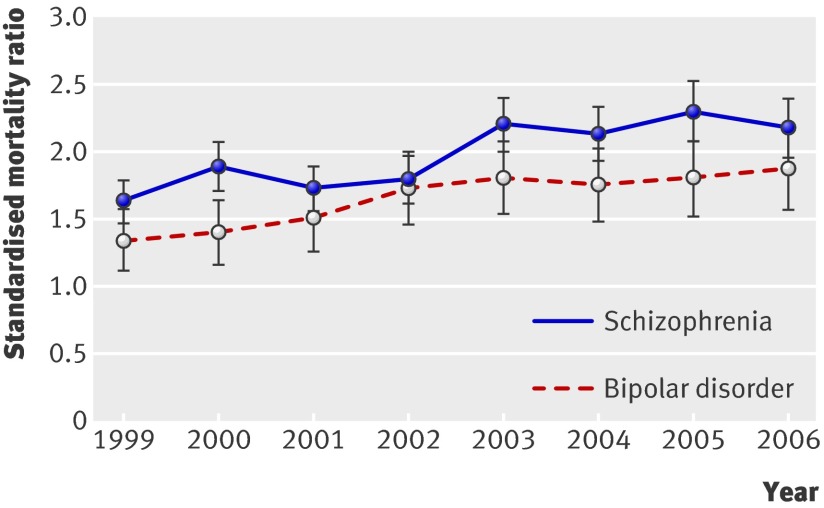

Results By 2006 standardised mortality ratios in the psychiatric cohorts were about double the population average. The mortality gap widened over time. For people discharged with schizophrenia, the ratio was 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 1.8) in 1999 and 2.2 (2.0 to 2.4) in 2006 (P<0.001 for trend). For bipolar disorder, the ratios were 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) in 1999 and 1.9 (1.6 to 2.2) in 2006 (P=0.06 for trend). Ratios were higher for unnatural than for natural causes. About three quarters of all deaths, however, were certified as natural, and increases in ratios for natural causes, especially circulatory disease and respiratory diseases, were the main components of the increase in all cause mortality.

Conclusions The total burden of premature deaths from natural causes in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder is substantial. There is a need for better understanding of the reasons for the persistent and increasing gap in mortality between discharged psychiatric patients and the general population, and for continued action to target risk factors for both natural and unnatural causes of death in people with serious mental illness.

Introduction

Schizophrenia has been described as a life shortening condition,1 and many studies have shown that people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder have higher mortality rates than the general population, both as a result of natural2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 and unnatural causes,2 3 4 5 6 including suicide. Over the past decade several strategies have been implemented in England and Wales aimed at reducing the mortality gap between people with serious mental illness and the general population, including those to address deliberate self harm and to reduce suicide,7 8 9 to decrease smoking,10 11 12 alcoholism, and drug misuse,13 14 and to deal with other lifestyles associated with increased mortality.15 16 Recent studies have suggested that the rate of suicide has been stabilising among people with mental disorders as a whole17 18 19 20 21; however, trends in mortality for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder remain poorly characterised, particularly the relative contributions of natural and unnatural causes. The United Kingdom government’s recent mental health strategy states that “more people with mental health problems will have good physical health” as one of its objectives, specifically stating that “fewer people with mental health problems will die prematurely.”22 It is therefore timely to review the level of and trends in these recognised inequalities.

We investigated trends in mortality between 1999 and 2006 during the year after discharge from hospital for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder as the principal diagnosis at discharge. We compared mortality in these populations with mortality in the general population of equivalent age in England to determine whether the “mortality gap” between people with these mental disorders and the general population has narrowed in recent years and to describe the relative contributions from natural and unnatural causes of death.

Method

Data sources and population included in this study

Our data for analysis came from a linked dataset of English national hospital episode statistics and data from death certification built by the team that developed and manages the Oxford record linkage study. The hospital episode statistics component of the dataset includes statistical abstracts of records of all inpatient episodes undertaken in National Health Service (NHS) trusts in England, including acute hospitals and mental health trusts. Information about deaths came from death certificates held by the Office for National Statistics. This information included the date of death and the causes of death, which were coded by the Office for National Statistics using the ninth and 10th revisions of the international classification of diseases (ICD-9 and ICD-10).

We extracted all records of discharges from inpatient care in England from 1 January 1999 to 31 December 2006 with either schizophrenia (ICD-10 codes F20-29) or bipolar affective disorder (ICD-10 code F31) as the principal diagnosis on the discharge record.

Our primary outcome was mortality within 365 days after psychiatric inpatient care as defined above. We also investigated deaths from unnatural and natural causes. Unnatural deaths were defined on the basis of ICD-10 codes V01-Y98 or ICD-9 codes E800-999 recorded anywhere on the death certificate; the remaining deaths were classified as natural. To allow more detailed interpretation of deaths under these broad categories we have also presented data for deaths from the following specific causes where there were sufficient deaths to provide a stable estimate of risk of mortality—namely, deaths from cardiovascular disease (ICD-10 codes I00-99, ICD-9 codes 390-459), respiratory disease (ICD-10 codes J00-99, ICD-9 codes 460-519), cancer (ICD-10 codes C00-D48, ICD-9 codes 140-239), accidents (ICD-10 codes V01-X59, ICD-9 codes E800-929), and suicide/deaths from undetermined intent (ICD-10 codes X60-89 and Y10-34, ICD-9 codes E950-959 and E980-989).

Analysis

We calculated mortality after hospital discharge as age and sex standardised mortality ratios, comparing mortality in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with mortality in the general population of England. Standardisation was done by using the indirect method, in five year age groups, with the age and sex specific mortality rates of England in the same time periods as the standard. These age and sex specific rates were applied to the age and sex structure of each of the discharge cohorts with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to calculate an “expected” number of deaths. The observed number was compared with the expected number to calculate the standardised mortality ratios. Its confidence intervals were calculated as described elsewhere.23 We further compared the mortality rates in three broad age groups: <45, 45-64, and 65-84 (with age standardisation, as above, using five year age groups within each truncated broader age group). We excluded analysis of those aged over 85 because of small numbers.

We used the Poisson test of trend to investigate whether there was a significant trend in standardised mortality ratios over time.24

Results

Trends in discharges with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

For this study we included 100 851 discharges from hospital for bipolar disorder and 272 248 discharges for schizophrenia in England for 1999-2006. Tables 1 and 2 show the basic demographic characteristics of the populations. Over the course of the study, the total number of discharges for bipolar disorder decreased by 3.9% from 12 369 to 11 888 (table 1) and the total number of discharges for schizophrenia decreased by 10.9% from 35 348 to 31 486 (table 2). About three in four of the deaths in each of the two cohorts were from natural causes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people discharged with principal diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-10 code F31) in England, 1999-2006

| Year of discharge | No of discharges | No of people discharged | % male | Median age (men/women) | Deaths within 365 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From all causes | From unnatural causes (% of all deaths) | |||||

| 1999 | 12 369 | 9312 | 38 | 42/48 | 132 | 30 (22.7) |

| 2000 | 12 285 | 9217 | 38 | 42/48 | 132 | 35 (26.5) |

| 2001 | 12 803 | 9384 | 38 | 43/48 | 143 | 40 (27.9) |

| 2002 | 13 153 | 9612 | 39 | 43/48 | 161 | 38 (23.6) |

| 2003 | 12 757 | 9723 | 39 | 44/48 | 175 | 46 (26.3) |

| 2004 | 13 221 | 10 102 | 40 | 43/48 | 158 | 51 (32.3) |

| 2005 | 12 375 | 9284 | 39 | 44/48 | 156 | 43 (27.6) |

| 2006 | 11 888 | 9086 | 41 | 44/48 | 148 | 38 (25.7) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of people discharged with principal diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10, codes F20-29) in England, 1999-2006

| Year of discharge | No of discharges | No of people discharged | % male | Median age (male/female) | Deaths within 365 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From all causes | From unnatural causes (% of all deaths) | |||||

| 1999 | 35 348 | 27 133 | 58 | 34/44 | 416 | 114 (27.4) |

| 2000 | 33 793 | 25 785 | 58 | 34/44 | 427 | 113 (26.5) |

| 2001 | 34 478 | 25 870 | 59 | 35/44 | 408 | 111 (27.2) |

| 2002 | 34 105 | 25 524 | 60 | 35/44 | 389 | 86 (22.1) |

| 2003 | 33 665 | 25 856 | 60 | 35/44 | 459 | 106 (23.1) |

| 2004 | 35 540 | 27 425 | 60 | 35/44 | 429 | 123 (28.7) |

| 2005 | 33 833 | 25 709 | 60 | 36/44 | 414 | 112 (27.1) |

| 2006 | 31 486 | 24 205 | 61 | 36/44 | 376 | 96 (25.5) |

Standardised mortality ratios for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

Age and sex standardised mortality ratios in the psychiatric cohorts were about double the population average. For example, in the 2006 cohort the ratio was 2.2 in the population discharged with schizophrenia and 1.9 in the population discharged with bipolar disorder. Standardised mortality ratios were higher in younger than in older people: in those aged under 45 discharged in 2006, the ratios were 6.2 (95% confidence interval 4.9 to 7.5) for schizophrenia and 3.4 (1.7 to 5.1) for bipolar disorder compared with 2.0 (1.7 to 2.3) and 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2), respectively, in people aged 65-84 (tables 3 and 4). Men with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia had a significantly higher risk of death within the first year than women. For example, in the 2006 cohort the standardised mortality ratio for men was 3.2 (2.8 to 3.6) and 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) for women (table 4). There was no significant sex difference in mortality risk for those discharged with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (table 3).

Table 3.

Age and sex standardised all cause mortality ratios in year after hospital discharge between 1999 and 2006 with principal diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-, 10, code F31) by age

| Year of discharge | All ages | <45 years | 45-64 years | 65-84 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men and women | ||||

| 1999 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| 2000 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| 2001 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 1.3 |

| 2002 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 1.6 |

| 2003 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| 2004 | 1.8 | 8.0 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| 2005 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| 2006 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Men | ||||

| 1999 | 1.7 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 2000 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| 2001 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 1.5 |

| 2002 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 2.5 | 1.6 |

| 2003 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 1.6 |

| 2004 | 2.3 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| 2005 | 2.0 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| 2006 | 2.3 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| Women | ||||

| 1999 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| 2000 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.2 |

| 2001 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| 2002 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 1.8 |

| 2003 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| 2004 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| 2005 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| 2006 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

Table 4.

Age and sex standardised all cause mortality ratios in year after hospital discharge between 1999 and 2006 with principal diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10, codes F20-29) by age

| Year of discharge | All ages | <45 years | 45-64 years | 65-84 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men and women | ||||

| 1999 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 3.4 | 1.3 |

| 2000 | 1.9 | 7.5 | 3.5 | 1.7 |

| 2001 | 1.7 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| 2002 | 1.8 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 1.6 |

| 2003 | 2.2 | 6.7 | 4.3 | 2.0 |

| 2004 | 2.1 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| 2005 | 2.3 | 9.1 | 3.5 | 1.9 |

| 2006 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 2.0 |

| Men | ||||

| 1999 | 2.3 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| 2000 | 2.6 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 1.8 |

| 2001 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| 2002 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 1.6 |

| 2003 | 2.9 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 2.0 |

| 2004 | 3.0 | 6.48 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

| 2005 | 3.3 | 8.7 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

| 2006 | 3.2 | 6.1 | 4.0 | 2.2 |

| Women | ||||

| 1999 | 1.6 | 7.3 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| 2000 | 1.9 | 8.2 | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| 2001 | 1.7 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 1.9 |

| 2002 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| 2003 | 2.0 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 2.1 |

| 2004 | 1.8 | 7.9 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| 2005 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 3.9 | 1.7 |

| 2006 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 2.1 |

Trends in mortality ratios

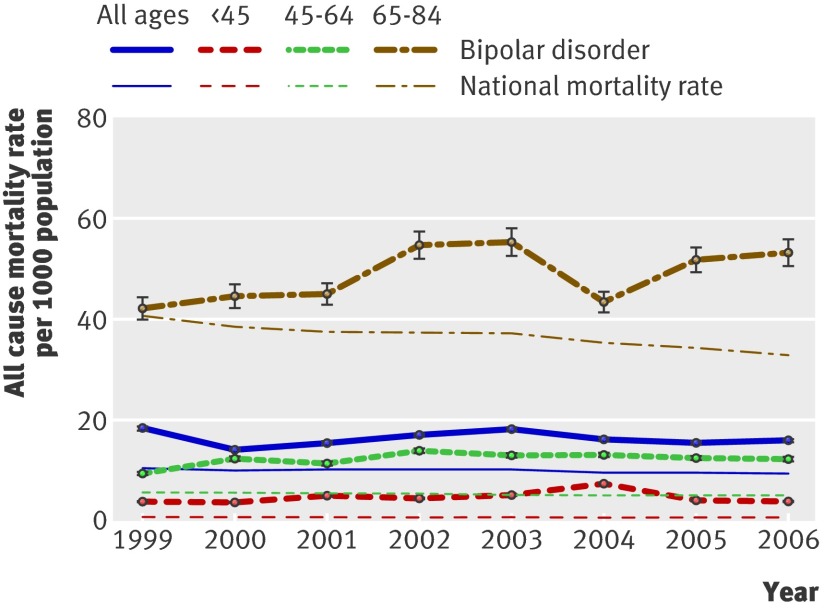

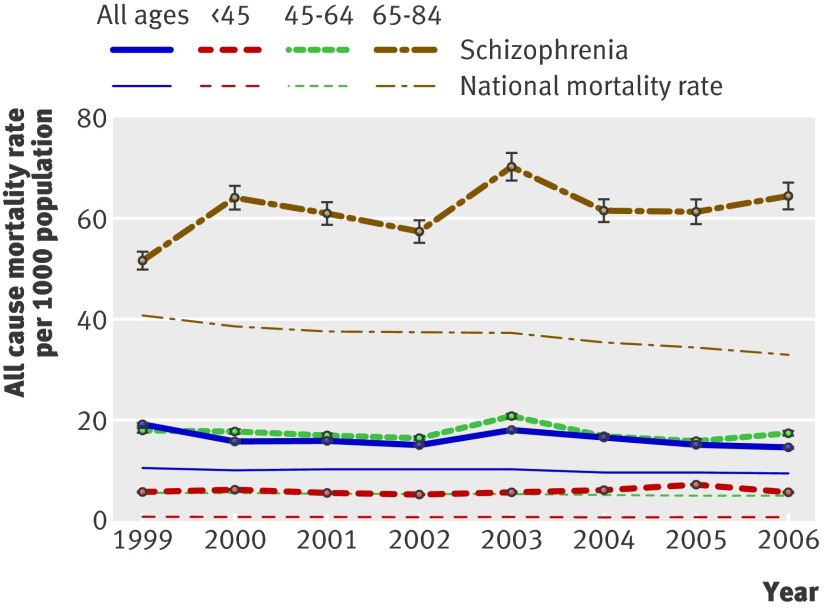

As shown in table 4 and figure 1, standardised mortality ratios for people with schizophrenia increased from 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) in people discharged in 1999 to 2.2 (2.0 to 2.4) in people discharged in 2006. The Poisson test for trend confirmed that the trend in risk of mortality was significant (P<0.001). For people with bipolar disorder, standardised mortality ratios increased from 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) in people discharged in 1999 to 1.9 (1.6 to 2.2) in people discharged in 2006 (table 3). The Poisson test of trend had results of borderline significance (P=0.06). Figures 2 and 3 summarise the data for the people with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and the general population expressed as rates (to give absolute values). While the mortality rates in the general population tended to decline over time, those in the populations with mental disorders did not. Compared with the mortality rate for the general population, the mortality gap remained fairly stable for adults aged under 65; for those aged 65-84, however, the mortality gap widened during the study period.

Fig 1 Trend in standardised 365 day all cause mortality ratio for all people discharged from hospital with principal diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia

Fig 2 All cause mortality rate within 365 days after discharge per 1000 people discharged with principal diagnosis of bipolar disorder by age

Fig 3 All cause mortality rate within 365 days after discharge per 1000 people discharged with principal diagnosis of schizophrenia by age

Standardised mortality ratios for unnatural/natural causes and specific causes

For unnatural causes, the standardised mortality ratios showed no evidence of a narrowing mortality gap. In people with schizophrenia they were 11.6 (9.5 to 13.7) in the 1999 cohort and 11.6 (9.3 to 13.9) in the 2006 cohort. The corresponding figures for bipolar disorder were 9.3 (6.0 to 12.7) and 12.6 (8.6 to 16.6). Numbers in individual age groups were small, but there was no evidence of a narrowing of the gap in any age group (table 5).

Table 5.

Age and sex standardised mortality ratios for unnatural causes of death in year after hospital discharge between 1999 and 2006 by age and principal diagnosis

| Year of discharge | All ages | <45 years | 45-64 years | 65-84 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar disorder (ICD-10, code F31) | ||||

| 1999 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 6.5 |

| 2000 | 11.0 | 9.4 | 17.6 | 9.5 |

| 2001 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 18.7 | 6.6 |

| 2002 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 21.2 | 4.2 |

| 2003 | 13.9 | 17.2 | 13.0 | 15.1 |

| 2004 | 15.6 | 22.3 | 18.9 | 7.1 |

| 2005 | 14.2 | 11.5 | 27.5 | 7.5 |

| 2006 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 15.4 | 10.5 |

| Schizophrenia (ICD-10, codes F20-29) | ||||

| 1999 | 11.6 | 15.2 | 16.0 | 3.9 |

| 2000 | 12.3 | 16.7 | 12.2 | 8.7 |

| 2001 | 11.6 | 15.0 | 16.6 | 7.3 |

| 2002 | 9.8 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 7.9 |

| 2003 | 11.9 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 9.9 |

| 2004 | 13.6 | 17.9 | 18.1 | 4.8 |

| 2005 | 13.8 | 19.3 | 13.1 | 8.2 |

| 2006 | 11.6 | 15.2 | 14.3 | 6.5 |

For natural causes, the mortality gap widened (table 6). For people with schizophrenia, the standardised mortality ratio was 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) in the 1999 cohort and 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) in the 2006 cohort. The corresponding figures for bipolar disorder were 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) and 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7). Table 7 shows that deaths from cardiovascular disease and respiratory diseases accounted for most of this increase. From 1999 to 2006, in those with schizophrenia, the standardised mortality ratios for circulatory disease rose from 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) to 2.5 (2.1 to 2.9), while the risk of death from respiratory disease increased from 3.1 (2.6 to 3.6) to 4.7 (3.8 to 5.6). The figures for those discharged with bipolar disorder rose from 1.6 (1.2 to 2.0) to 2.5 (1.9 to 3.1) for circulatory disease and from 3.0 (2.1 to 3.8) to 5.8 (4.3 to 7.3) for respiratory disease.

Table 6.

Age and sex standardised mortality ratios for natural causes of death in year after hospital discharge between 1999 and 2006 by age and principal diagnosis

| Year of discharge | All ages | <45 years | 45-64 years | 65-84 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar disorder (ICD-10, code F31) | ||||

| 1999 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 2000 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| 2001 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| 2002 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| 2003 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| 2004 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 2005 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| 2006 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Schizophrenia (ICD-10, codes F20-29) | ||||

| 1999 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| 2000 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

| 2001 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.6 |

| 2002 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| 2003 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| 2004 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 1.7 |

| 2005 | 1.8 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| 2006 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 1.8 |

Table 7.

Age and sex standardised mortality ratios for death in year after hospital discharge between 1999 and 2006 by principal psychiatric diagnosis and specific cause of death

| Year of discharge | Circulatory disease* | Cancer† | Respiratory disease‡ | Accidents§ | Suicide and undetermined intent¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar disorder (ICD-10, code F31) | |||||

| 1999 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 6.8 | 13.5 |

| 2000 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 21.2 |

| 2001 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 24.8 |

| 2002 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 20.2 |

| 2003 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 27.7 |

| 2004 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 32.1 |

| 2005 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 29.5 |

| 2006 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 19.8 |

| Schizophrenia (ICD-10, codes F20-29) | |||||

| 1999 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 6.5 | 19.5 |

| 2000 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 19.6 |

| 2001 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 21.8 |

| 2002 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 17.8 |

| 2003 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 23.3 |

| 2004 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 24.7 |

| 2005 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 24.0 |

| 2006 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 20.9 |

*ICD-10: I00-I99; ICD-9: 390-459.

†ICD-10: C00-D48; ICD-9: 140-239.

‡ICD-10: J00-99; ICD-9: 460-519.

§ICD-10: V01-X59; ICD9: E800-E929.

¶ICD-10: X60-X84, Y10-Y34; ICD-9: E950-E959, E980-E989.

Discussion

Principal findings

The risk of death for people recently discharged from inpatient psychiatric care in England is significantly higher than that in the general population. This excess risk was observed for patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and for those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Our findings of a persistent mortality gap in England in patients discharged between 1999 and 2006 are similar to results recently published by Tiihonen et al on all cause mortality in people with schizophrenia over a similar time period in Finland.25 26 Additionally, our findings suggest that the differential mortality for people with schizophrenia has widened in some groups, a result that is similar to the findings from a systematic review by Saha et al in 2007.27 Much of the increase in mortality is attributable to deaths from natural causes, especially circulatory disease and respiratory disease. Our findings support the recommendation of Saha et al that “in light of the potential for second-generation antipsychotic medications to further adversely influence mortality rates . . . optimizing the general health of people with schizophrenia warrants urgent attention.”27

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include its large size and the fact that it includes all records of discharges with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in the study period and is therefore nationally representative. By linkage to national mortality data we have included comprehensive information on mortality in these vulnerable groups, especially in the period after discharge from hospital when the risk of death is greatest.2 In addition, to the best of our knowledge, ours are the first published findings on trends in mortality over the past decade for people with bipolar disorder in England, a condition that shares some clinical and management characteristics with schizophrenia.28 These study characteristics aid the generalisability of our findings compared with previous studies in the UK, which have been limited to case registers within individual mental health trusts.29 30

To quantify the mortality gap and assess the trend in risk of mortality for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, we calculated standardised mortality ratios, which take into account differences in the age structure of the cases, as well as changes in the underlying mortality rates of the general population. The widening gap in standardised mortality ratios alone could represent an absolute rise in mortality in the psychiatric population or a fall in mortality in the general population in conjunction with a smaller fall in mortality in the psychiatric population. Accordingly, we have presented rates for all causes of death after discharge compared with national mortality rates over the same period, which allowed us to compare trends in the absolute difference in mortality risk between the groups. Both figures—the standardised mortality ratios and the rates—show that the risk of mortality after discharge is substantial and that the gap in risk, whether calculated in relative or absolute terms, remains substantial. The standardised mortality ratios for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder towards the end of this observation period are similar to those recently reported from the South London and Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre psychiatric case register for 2007-9, which also found a similarly pronounced excess in younger patients.29

Potential limitations include the usual caveats concerning the use of routinely collected data, including information from hospital records and death certificates, which are not collected for research purposes.31 32 33 34 There are also caveats about the validity of a dichotomy between “natural” and “unnatural” categories of death, although the definitions of these categories from the ICD codes were standard.35 36 The case groups consisted of people who had been recently admitted to hospital with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder during the period in question and cannot be said to represent all people with the disorders; they are likely to represent a more severely affected group at a period of higher risk. The severity of the disorders in the case groups might have changed over the monitoring period because of changes in admission policy. Keown et al found little evidence of any significant decrease in admissions for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during this period,37 and our finding of minor reductions in discharges over the observation period compared with the increases in standardised mortality ratios suggests that the concentration of mortality risk in these patients admitted to hospital is unlikely to be the sole explanation for the widening mortality gap, although residual confounding with severity of illness cannot be excluded entirely.

Interpretation, unanswered questions, and need for further work

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are known to be associated with a higher risk of mortality.1 Over the past decade the contribution of natural causes to excess mortality in people with severe mental illness has been increasingly recognised, particularly the impact of coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer.38 For example, Osborn and colleagues used information from the UK General Practice Research Database to follow up a community sample of people with severe mental illness and found that these people had a significantly increased risk of death from coronary heart disease and stroke compared with controls that was not wholly explained by antipsychotic medication, smoking, or social deprivation.39

While knowledge about the specific causes of death in severe mental illness are becoming clearer, the pathogenic mechanisms that culminate in higher than expected mortality from natural causes in people with mental disorder are little understood and likely to be complex.40 41 Mechanisms acting through the direct effects of symptoms of mental disorder are unlikely to have a large effect on mortality from natural causes, although they are likely to influence death from suicide and other unnatural causes.42 Premature deaths from natural causes are likely to be influenced by adverse lifestyle and social factors associated with the presence of mental illness—such as smoking, use of alcohol and illicit drugs, and exposure to poor housing and social conditions40 43—or the adverse effects of antipsychotic medication.44 45 It has been suggested, however, that these factors do not account for all the excess mortality,39 and there is an urgent need for more research to understand the contribution of the six leading global risk factors for mortality identified by WHO—namely, hypertension, smoking, raised glucose concentration, physical inactivity, overweight and obesity, and high cholesterol concentration—to excess mortality in people with severe mental illness, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.41

Our results reinforce the need for further research in the UK as the mortality gap has not decreased and is increasing in some groups, such as those aged over 65. These results have particular policy relevance in the context of the implementation of the new national mental health strategy in England. They strongly point to the need for continued action to target risk factors for both natural and unnatural causes of death, including known risk factors for circulatory and respiratory disease, particularly to lower the risk for these people in the year after discharge from hospital. It is encouraging that the government has recognised and prioritised the importance of preventing premature mortality in its recently published mental health strategy.22 A reduction of the gap is also a challenge for the forthcoming reorganisation of the NHS in England, for general practitioner commissioning, and for the reorganisation’s emphasis on an NHS driven by outcomes. The already widening mortality gap between people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and the general population, however, suggests that these policies might be challenging aspirations.

What is already known on this topic

People with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder have higher mortality rates than the general population, both as a result of natural and unnatural causes

Recent evidence suggests that the rate of suicide and death from unnatural causes has been stabilising among people with mental illness in the UK

The English government’s recent mental health strategy has stated clearly that “fewer people with mental health problems will die prematurely”

What this study adds

The mortality gap between people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who have been recently discharged from hospital and the general population persisted between 1999 and 2006 in England

For some age groups, such as those aged 65-84, the mortality gap has increased

Most of this excess mortality was the result of deaths from natural causes, especially deaths from circulatory and respiratory diseases

Contributors: UH and MG were responsible for the conception and design of this study. UH analysed the data. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data, drafting the article, and approval of the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. UH is guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded in part by the English National Institute for Health Research. RS is funded by the NIHR Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. UH is an academic clinical fellow at the Oxford University Clinical Academic Graduate School and the Oxford School of Public Health. The work of the authors is independent from the funders of this research. The funders were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The current work programme of analysis using the linked datasets held at the unit of health-care epidemiology was approved by an ethics committee of the NHS central office for research (reference No 04/Q2006/176).

Data sharing: Hospital Episodes Statistics and mortality data can be obtained through the NHS Information Centre and the Office for National Statistics, respectively. More detailed aggregated statistical tables than those shown in this paper are available from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d5422

References

- 1.Allebeck P. Schizophrenia: a life-shortening disease. Schizophr Bull 1989;15:81-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldacre M, V Seagroatt, K Hawton. Suicide after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care. Lancet 1993;342:283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall DJ, O’Brien F, Stark C, Pelosi A, Smith H. Thirteen-year follow-up of deliberate self-harm, using linked data. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:239-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:205-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiroeh U, Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Dunn G. Death by homicide, suicide, and other unnatural causes in people with mental illness: a population-based study. Lancet 2001;358:2110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gau SSF, Cheng ATA. Mental illness and accidental death: case-control psychological autopsy study. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Service Framework for Mental Health; modern standards and service models. Department of Health, 1999.

- 8.National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England. Department of Health. 2002.

- 9.National Framework for the Prevention of Suicide and Deliberate Self-Harm in Scotland. Scottish Executive, 2002.

- 10.Moving towards smoke-free in mental health services in Scotland. NHS Health Scotland, 2008.

- 11.Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008.

- 12.Health Bill. Department of Health, 2009.

- 13.Drug misuse: opioid detoxification. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007.

- 14.Drug misuse: psychosocial interventions. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. [PubMed]

- 15.Choosing health: making healthier life choices. Department of Health, 2004.

- 16.Public health white paper. Department of Health, 2009.

- 17.Biddle L, Brock A, Brookes ST, Gunnell D. Suicide rates in young men in England and Wales in the 21st century: time trend study. BMJ 2008;336:539-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deaths 1901-2000: deaths from injury and poisoning: external cause and year of registration or occurrence. Mortality statistics: injury and poisoning (series DH4 no 26). Office for National Statistics, 2005.

- 19.Griffiths C, Wright O, Rooney C. Trends in injury and poisoning mortality using the ICE on injury statistics matrix, England and Wales, 1979-2004. Health Stat Q 2006;32:5-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Life expectancy and all age all cause mortality monitoring (overall and health inequalities)—update to include data for 2007. Department of Health, 2008.

- 21.Kapur N, Hunt IM, Webb R, Bickley H, Windfuhr K, Shaw J, et al. Suicide in psychiatric in-patients in England, 1997 to 2003. Psychol Med 2006;36:1485-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.No health without mental health: a cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. Department of Health, 2010.

- 23.Higham J, Flowers J, Hall P. Standardisation. Eastern Region Public Health Observatory, 2005.

- 24.Breslow N, Day N. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol II: the design and analysis of cohort studies. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1987. [PubMed]

- 25.Chwastiak LA, Tek C. The unchanging mortality gap for people with schizophrenia. Lancet 2009;374:590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet 2009;374:620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J, A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1123-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelder M, Andreasen N, Lopez-Ibor J, Geddes J. New Oxford textbook of psychiatry. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- 29.Chang CK, Hayes RD, Broadbent M, Fernandes AC, Lee W, Hotopf M, et al. All-cause mortality among people with serious mental illness (SMI), substance use disorders, and depressive disorders in southeast London: a cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassall C, Prior P, Cross KW. A preliminary study of excess mortality using a psychiatric case register. J Epidemiol Community Health 1988;42:286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrne N, Regan C, Howard L. Administrative registers in psychiatric research: a systematic review of validity studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;112:409-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldacre M, Shiwach R, Yeates D. Estimating incidence and prevalence of treated psychiatric disorders from routine statistics: the example of schizophrenia in Oxfordshire. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:318-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldacre MJ, Duncan ME, Griffith M, Cook-Mozaffari P. Psychiatric disorders certified on death certificates in an English population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:409-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins N, Howard L. Database use in psychiatric research: an international review. Eur J Psychiatry 2005;19:19-30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:116-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordentoft M, Breum L, Nordestgaard AG, Hunding A, Laursen Bjaeldager PA. High mortality by natural and unnatural causes: a 10 year follow up study of patients admitted to a poisoning treatment centre after suicide attempts. BMJ 1993;306:1637-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keown P, Mercer G, Scott J. Retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics, involuntary admissions under the Mental Health Act 1983, and number of psychiatric beds in England 1996-2006. BMJ 2008;337:a1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24:17-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osborn DPJ, Levy G, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Islam A, King M. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leucht S, Burkard T, Henderson JH, Maj M, Sartorius N. Physical illness and schizophrenia. Cambridge University Press, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wildgust HJ, Hodgson R, Beary M. The paradox of premature mortality in schizophrenia: new research questions. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24:9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutta R, Murray RM, Allardyce J, Jones PB, Boydell J. Early risk factors for suicide in an epidemiological first episode psychosis cohort. Schizophr Res 2011;126:11-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robson D, Gray R. Serious mental illness and physical health problems: a discussion paper. Int J Nursing Stud 2007;44:457-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson M. Risk of cardiovascular disease and sudden death in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;9:5-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sicouri S, Antzelevitch C. Sudden cardiac death secondary to antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2008;7:181-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]