Abstract

Monteggia fracture dislocations are uncommon in childhood. Over a period of time, various equivalents of this entity have been described. These fractures with concomitant elbow injuries are exceedingly rare in young children. We present a case of a 6-year-old boy who sustained a fracture of proximal ulna with ipsilateral supracondylar fracture humerus. We suggest that the fracture pattern can be included under type I Monteggia equivalent on the basis of its characteristics, biomechanics and the mode of injury.

Keywords: Monteggia lesions, Monteggia equivalents, Supracondylar fracture

Introduction

Since the first description, Monteggia fracture dislocations have been problem injuries in the terms of diagnosis, mechanism of injury, treatment and its outcome. Its first description dates back to 1814, when Giovanni Battista Monteggia first observed this entity [1]. Shortly before his death, he wrote [2]…

“…I unhappily remember the case of a girl who seemed to me to have sustained a fracture of the upper third of the ulna. At the end of a month of bandaging, the head of the radius dislocated when I extended the forearm. I applied a new bandage but the head of the radius would not stay in place…”

Bado described ‘true Monteggia lesions’ and classified them into four types [3]. He also classified certain injuries as equivalents to the ‘true Monteggia lesions’ based on their similar radiographic pattern and biomechanism of injury and ‘Monteggia equivalent’ term was used for these patterns. Since then various types and their equivalents have been described in the literature. We present a rare case which can be included under type I Monteggia equivalent on the basis of its characteristics, biomechanics and the mode of injury.

Case Report

A 6-year-old boy sustained a fall from a height of about 6 ft and landed on his outstretched left hand and sustained an injury to the left forearm and ipsilateral elbow. He presented to the emergency department approximately 12 h after sustaining the injury with the complaints of swelling, severe pain and restricted motion of left elbow. On examination, his vitals were stable. Left elbow displayed gross swelling and deformity. Forearm was in the attitude of pronation. Painful abnormal mobility and crepitus were present both at the elbow and the ulnar aspect of forearm. There was no bruising and fractures were closed. There was no distal neurovascular deficit in the extremity. It was not associated with other significant systemic injury. Roentgenograms showed a fracture of ulnar diaphysis at proximal and middle third junction with 200 of anterior angulation. There was also an ipsilateral Gartland type 3 extension type of supracondylar humerus fracture (Figs. 1 and 2). The patient was treated with closed reduction followed by above elbow Plaster of Paris (POP) slab under sedation. The parents were advised for closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, but they wished to be managed conservatively. Hence the patient was planned for continuation of nonoperative treatment (Fig. 3). Since the radiographs taken on 3rd and 7th day follow-up revealed no further displacement, it was converted to a cast after 2 weeks. Both the fractures healed at 6 weeks and he regained the full range of flexion, extension, and rotations with bony union at 12 months following physiotherapy (Fig. 4).

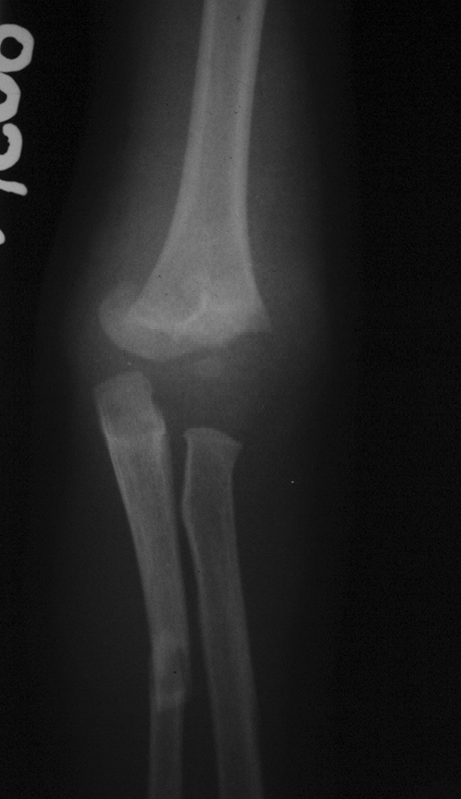

Fig. 1.

Pre reduction AP radiograph showing displaced supracondylar fracture humerus with fracture of middle third shaft of ulna

Fig. 2.

Pre reduction lateral radiograph showing supracondylar fracture humerus (Gartland type 3) with fracture of middle third shaft of ulna (200 anterior angulation)

Fig. 3.

Post-reduction radiograph showing acceptable alignment

Fig. 4.

Follow-up radiograph at 12 months showing fracture healing with acceptable alignment

A written informed consent was obtained authorizing treatment, radiological examination and photographic documentation. The parents were informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication and they consented.

Discussion

Monteggia fracture dislocation in a child is an uncommon injury [3] consisting approximately 1.5%–3% of the elbow injuries in the childhood. Essentially, the lesion consists of dislocation of the head of the radius with a fracture of ulna at various levels. Bado, in a series of 40 patients, recognized 4 patterns and classified them according to the direction of dislocation of the radial head [3]. He suggested that these injury types should be referred to as “Monteggia lesions” [3, 4] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Various Monteggia lesions and proposed mechanism of injury

| Direction of radial head dislocation | Ulna fracture | Mechanism of injury | Incidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Anterior | Anterior angulation, usually midshaft | Hyperextension, Hyperpronation, Direct blow (?) | ~70% |

| Type II | Posterior | Posterior angulation, diaphyseal or metaphyseal | Hyperflexion | ~3%–5% |

| Type III | Lateral or anterolateral | Lateral angulation, Metaphyseal, usually greenstick | Hyperextension, Lateral varus stress | ~23%–26% |

| Type IV | Anterior, with fracture radius shaft at same level or distal to ulna fracture | Diaphyseal | Hyperpronation | <1% |

Bado also supplemented his classification to accommodate some unusual varieties, which he called ‘equivalents’ or ‘Monteggia like lesions’ [3]. He described three equivalents (all were type I equivalents), which included (1) isolated radial head dislocation (with plastic deformation of ulna), (2) fracture of proximal ulna with fracture of the radial neck and (3) both-bone proximal third fractures with the radial fracture more proximal than the ulnar fracture [5]. Over a period of time various other equivalents of type I Monteggia have been described which included pulled elbow syndrome, isolated radial neck fracture, fracture of ulnar diaphysis with anterior dislocation of radial head and an olecranon fracture [6] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Various fracture pattern under Monteggia equivalents

| Type I Monteggia equivalents [6]: | Type II Monteggia equivalent [6]: |

|---|---|

| Isolated anterior dislocation of radial head (with plastic deformation of ulna) | Posterior elbow dislocation in children |

| Isolated radial neck fracture | |

| Pulled elbow syndrome | Type III Monteggia equivalent [6, 9]: |

| Fracture of the ulnar diaphysis with fracture of radial neck | Oblique fracture of ulna (with varus malalignment) with displaced fracture of the lateral condyle of humerus |

| Fractures of both bones in forearm (wherein, the radial fracture is above the junction of the proximal and the middle third) | |

| Fracture of ulnar diaphysis with anterior dislocation of radial head and an olecranon fracture | Type IV Monteggia equivalent [6, 10]: |

| Fracture of ulnar diaphysis (at proximal and middle third junction) with displaced extension type supracondylar fracture of humerus (present case) | Distal humerus fracture with proximal third ulnar diaphysis fracture and distal radial metaphyseal fracture with anterior dislocation of radial head |

Though Bado stated that there were no equivalents of type II, III, IV Monteggia, but various investigators have described other equivalents also on the basis of fracture characteristics, biomechanics and the mode of injury [3, 5, 6]. Considering the mechanism of injury as defined by Penrose [7] in type II Monteggia lesion, a posterior elbow dislocation could be considered as type II equivalent [6]. Similarly, considering the hyperextension and lateral varus stress as the mechanism of injury, as defined by Wright in type III Monteggia lesion, the case reported by Ravessoud was considered as type III equivalent [4, 6, 8, 9]. He reported an oblique fracture of the ulna with varus malalignment and an ipsilateral displaced fracture lateral condyle humerus in a 13 year-old-patient [9] (Table 2). A case reported by Arazi et al. was considered as type IV equivalent because the case (13 year-old-girl) sustained Monteggia fracture dislocation along with an ipsilateral distal humerus and distal radius fracture [6, 10] (Table 2). Similar fracture patterns were also reported by Rouhani et al. and Powell et al. [11, 12]. Monteggia fracture dislocation with intercondylar fracture humerus was reported in skeletally mature patients by Beredjiklian et al. [13] and Amite et al. [14] but they could not further subtype the fracture. The results of Monteggia fracture pattern in children have been reported to better than adults [15].

It is usually very difficult to determine the exact mechanism of injury in a very young child, who is usually unable to provide precise details of the sequence of events [16]. However, the position of the forearm when the patient is first seen, the position of the distal radius on roentgenograms, the direction of dislocation of radial head, and the direction of angulation of ulnar fracture, all provide indirect clues about the mechanism of injury [17]. One of the most widely accepted theories is that isolated Monteggia fracture–dislocation is caused by hyperpronation as described by Evans [18]. However, Tompkins postulated that hyperextension of the elbow plays significant role in causing this injury [19]. In our case, probably both of these indirect mechanisms, hyperextension and hyperpronation, were involved considering the facts that there was presence of anterior angulation in ulnar fracture and forearm was in the attitude of pronation when patient presented to us (which was further confirmed by roentgenogram of the wrist with the extremity in same position, which revealed that the distal epiphysis of radius and ulna were at the same level). The patient having suffered a fall on the outstretched hand, it seems logical to believe that the load transmission from distal to proximal and from radius to ulna across the interrosseous membrane resulted initially in the ulnar fracture. The continuing hyperextension force which usually results in the dislocation of radial head in a Monteggia ‘lesion’ along with continuing hyperpronation force could have resulted, instead, in a supracondylar humerus fracture. The excessive forces acting in and around a joint may result in capsulo-ligamentous or bony failure on a case to case basis. Instead of the anterior dislocation of the radial head or the radial neck fracture, intact radio-capitellar and proximal radio-ulnar joints moved along with the supracondylar fragment in the attitude of deforming force i.e. pronation, and thus leading to postero-medial type of supracondylar fracture pattern (Fig. 5). Thus, the postero-medial displacement of the supracondylar humerus fracture may well corroborate with the described mechanism of injury.

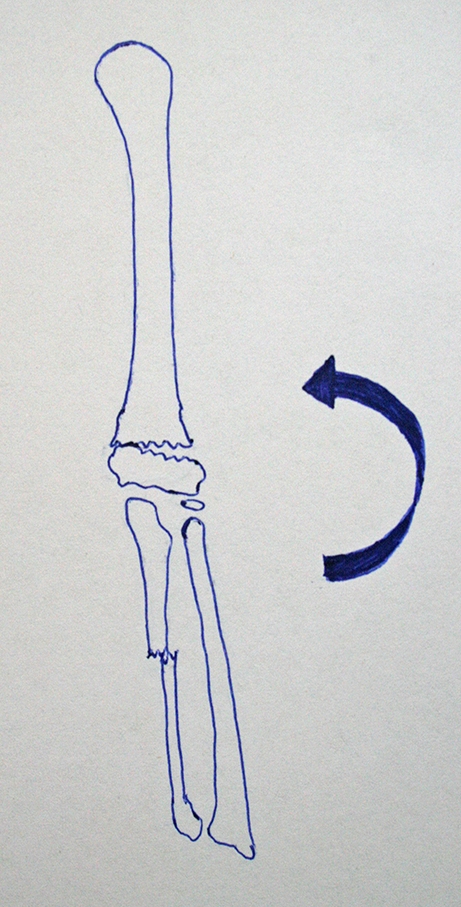

Fig. 5.

Line diagram showing hyperpronation force, which lead to failure of supracondylar area of humerus before radial head dislocation or fracture of radial neck. Instead of the anterior dislocation of the radial head or the radial neck fracture, intact radio-capitellar and proximal radio-ulnar joints moved along with distal supracondylar fragment in the attitude of deforming force

Concomitant supracondylar and ulnar diaphyseal fractures are exceedingly rare in young children. All the published studies of Monteggia fractures with ipsilateral distal humerus or intercondylar fractures were described in adults or older children, most of them were compound, were caused by high speed trauma with other significant systemic injuries, and some of them were designated as Monteggia type III or IV equivalents as described above. We describe our case, a 6-year-old boy, who sustained fracture diaphysis ulna with ipsilateral extension type fracture supracondylar fracture humerus after a simple fall, and recommend it to be included under type I Monteggia equivalent based on the fracture characteristics, biomechanics and mode of injury.

References

- 1.Peltier LF. Eponymic fractures: Giovanni Battista Monteggia and Monteggia’s fracture. Surgery. 1957;42:585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monteggia GB. Instituzioni chirurgiche. Milan: Maspero. 1814;5:130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;50:71–86. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dormans JP, Rang M. The problem of Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1990;21(2):251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terry Canale S. Fractures and dislocations in children. In: Terry Canale S, editor. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. Vol. Two. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1391–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garza JF. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. In: Beaty JH, Kasser JR, editors. Rockwood and Wilkin’s Fractures in Children. 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 491–528. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penrose JH. The Monteggia fracture with posterior dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1951;33:65–73. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.33B1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright PR. Greenstick fracture of the upper end of the ulna with dislocation of the radio-humeral joint or displacement of the superior radial epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963;45:727–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravessoud F. Lateral condyle fracture and ipsilateral ulnar shaft fracture: Monteggia equivalent lesions. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5:364–6. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198505000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arazi M, Ogun TC, Kapicioglu MF. The Monteggia lesion and ipsilateral supracondylar humerus and distal radius fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13:60–66. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199901000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouhani AR, Navali AM, Sadegpoor AR, Soleimanpoor J, Ansari M. Monteggia lesion and ipsilateral humeral supracondylar and distal radial fractures in a young girl. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(7):1127–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell RS, Bowe JA. Ipsilateral supracondylar humerus fracture and Monteggia lesion: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(10):737–40. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Ramsey ML. Ipsilateral intercondylar distal humerus fracture and Monteggia fracture-dislocation in adults. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(6):438–40. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pankaj A, Malhotra R, Bhan S. Monteggia fracture-dislocation with intercondylar fracture of the ipsilateral humerus: an unusual Monteggia variant. Injury Extra. 2005;36(3):51–4. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givon U, Pritsch M, Levy O, Yosepovich A, Amit Y, Horoszowski H. Monteggia and equivalent lesions: a study of 41 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;337:208–15. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199704000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiley JJ, Galey JP. Monteggia injuries in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:728–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B5.4055870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhandari N, Jindal P. Monteggia lesions in a child: variant of a Bado type-IV lesion. A case report. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1996;78:1252–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans EM. Pronation injuries of the forearm with special reference to the anterior Monteggia fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1949;31:578–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tompkins DG. The anterior Monteggia fracture: observations on etiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:1109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]