Abstract

Fifty years ago, the group of Tony Mathias and Bob Rabin at University College London, deduced the first mechanism for catalysis by an enzyme—ribonuclease (Findlay, D., Herries, D. G., Mathias, A. P., Rabin, B. R., and Ross, C.A. (1961). The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease, Nature 190, 781–784). Here, we celebrate this historic accomplishment by surveying knowledge of enzymology and protein science at that time, facts that led to the formulation of the mechanism, criticisms and alternative mechanisms, data that supported the proposed mechanism, and some of the refinements that have since provided a more precise picture of catalysis of RNA cleavage by ribonucleases. The Mathias and Rabin mechanism has appeared in numerous textbooks, monographs, and reviews, and continues to have a profound impact on biochemistry.

Keywords: General acid–base catalysis, histidine, Mathias, Rabin

The enzymatic reaction mechanism of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A1) was put forward in 1961—50 years ago2—by the group of Bob Rabin and (the late) Tony Mathias at University College London. In a paper to Nature (1), they presented a summary of the experimental work that was described in detail a year later (2–6). Their catalytic mechanism was the first in which clear roles were assigned to functional groups of a protein. Other mechanisms followed soon, such as those of chymotrypsin (7) and lysozyme (8). Although some refinements have been added to the original mechanism, its basic characteristics are still accepted, 50 years after its publication, as those that represent best the catalytic process. In this article, we recall the basic experiments that enabled its formulation, the criticisms that were raised, the alternative mechanisms put forward, and the refinements added later.

It is of the greatest historical significance that the experimental tools at hand in 1961 were, by the standards of 2011, quite unsophisticated. For example, it was not until 1963 that the complete sequence of RNase A was reported (9). Nothing was known about the three-dimensional structure of the protein, which was not determined until 1967 at low resolution (10), and 1969 at high resolution (11). As to studies using NMR spectroscopy, the first to be reported were those of the group of Roberts and Jardetzky in 1969 (12), experiments done at only 100 MHz. Recombinant DNA techniques were not available until the 1980’s. Thus, only their chemical modification implicated amino-acid residues in catalytic events.

WHY STUDY RIBONUCLEASE?

RNase A was one of the first enzymes attainable in large amounts in a purified, crystalline form (13). In addition, the Armour Company prepared a kilogram lot of the enzyme that was distributed among different laboratories to promote a deepening knowledge of protein molecules (14). That availability, added to some of the properties of the enzyme, such as its stability, lack of a cofactor, and small molecular size, favored RNase A as a protein of choice for a large number of studies that covered virtually all fields of protein research. (For a review, see: Richards and Wyckoff (15)).

For enzymologists, however, there existed an important impediment to studying RNase A—the extreme complexity of its substrate, RNA. It was impossible to make measurements that could be subjected to rational kinetic analysis with such a vaguely defined substrate. Markham and Smith had, however, demonstrated that both the alkaline- and the RNase A-catalyzed breakdown of RNA took place in two steps. In the first step, a 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide was formed; in the second step, this cyclic nucleotide was hydrolyzed to a 3′-nucleotide by RNase A and to a mixture of 2′- and 3′-nucleotides by alkali (16). The synthesis of reasonably pure cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide (17) allowed the development of an assay method for RNase A that yielded precisely quantifiable data (18). This assay was the basis for the kinetic experiments used to derive the mechanism.

SOME RELEVANT FACTS KNOWN AT THE TIME

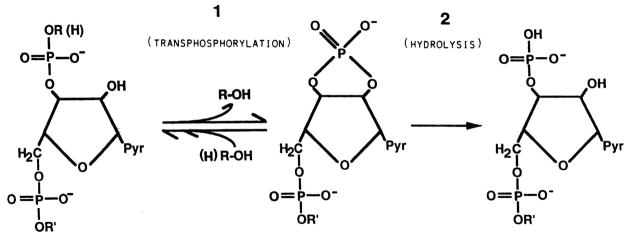

With respect to the catalytic mechanism of RNase A proposed by the group of Mathias and Rabin, the most relevant facts known in 1961 were as follows. (1) The breakdown of RNA catalyzed by RNase A took place, as noted above (16), in two steps: a transphosphorylation step in which a 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide was formed at the 3′ terminus of one product as a 5′-hydroxyl group appeared at the 5′ terminus of the other product. In the second step, the 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide was hydrolyzed to a 3′-nucleotide (Fig. 1). The first step was reversible, whereas the second was practically irreversible. In addition, the second step of the reaction was, formally, the reverse of the first (see below). (2) The RNase A sequence was known in part because of studies by the group of Stein and Moore which, incidentally, led to the development of the automated amino-acid analyzer. (3) The chemical modification studies of Barnard and Stein identified His119 as the residue reacting with bromoacetic acid at pH values near neutrality that was necessary for the catalytic activity of RNase A (19). (4) RNase A was known to have a preference for cleaving phosphodiester bonds in RNA on 3′ side of pyrimidine residues (20).

Fig. 1.

Transphosphorylation and hydrolysis reactions catalyzed by RNase A. (Reproduced with permission from Scheme 1 of Cuchillo et al. (53).)

WORK THAT LED TO THE MECHANISM

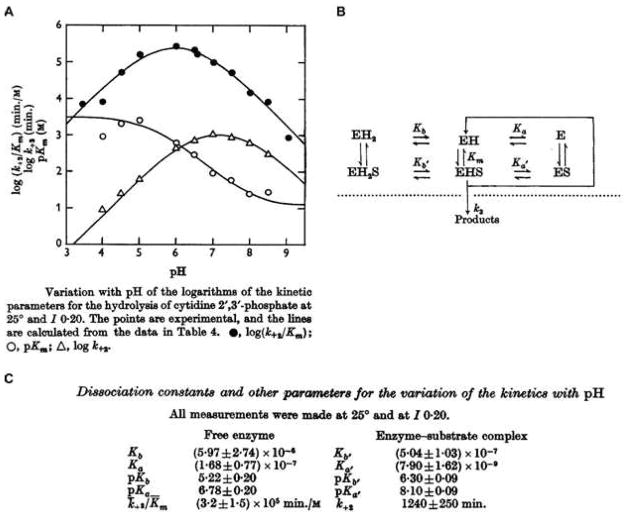

In 1962, the group of Mathias and Rabin reported on the detailed experiments that led to the formulation of the ribonuclease mechanism in a series of five papers in the Biochemical Journal (2–6). The papers were numbered 3–7 because they followed two papers published in 1960 (17, 18). In the first of the 1962 papers (2), the group studied the kinetics of RNase A, using cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate as substrate, as a function of pH. The results, of the type shown in Fig. 2A,3 were interpreted using a kinetic scheme (Fig. 2B) that enabled derivation of acid dissociation constants (Fig. 2C). The data showed that the pKa values of two functional groups increased upon binding to the substrate, and that the pKa values of these groups were consistent with their being the imidazoyl groups of histidine side chains.

Fig. 2.

pH–Rate profiles for catalysis of the hydrolysis of cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate by RNase A. (A) Data. (B) Interpretative scheme. (C) Derived parameters. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 6, Scheme 2, and Table 4 of Herries et al. (2).)

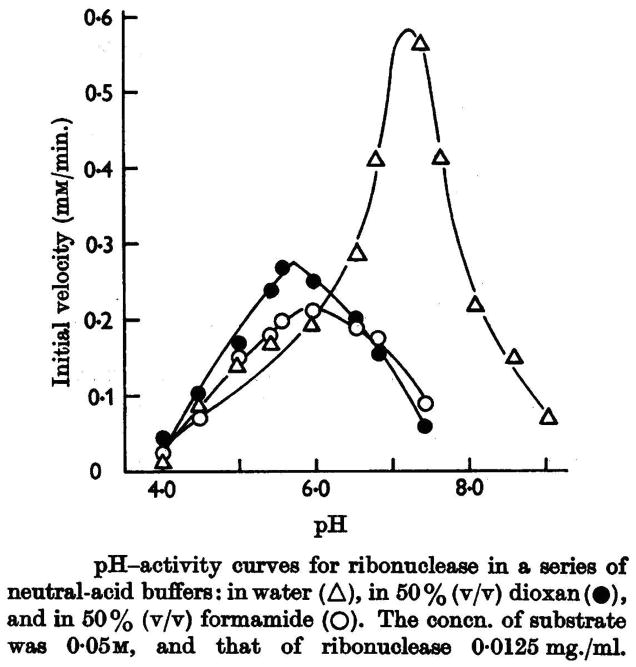

In the second and third papers (3, 4) of the 1962 series, the group of Mathias and Rabin studied the effect of organic solvents on the kinetics of the reaction, again using cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate as substrate. The results (Fig. 3) showed that the acidic group involved in catalysis was a cationic acid of the type AH+ (like an imidazolium ion) and not a neutral acid of the AH type. In addition, they showed that methanolysis of the substrate catalyzed by the enzyme (which is the formal reverse of the first step of the reaction) was much faster than hydrolysis, concluding that the 5′ side of the substrate had to interact in some way with the enzyme.

Fig. 3.

Solvent-dependence of the pH–rate profiles for catalysis of the hydrolysis of cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate by RNase A. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 4 of Findlay et al. (4).)

In the fourth paper of that series (5), the group of Mathias and Rabin studied the binding of Zn2+ to RNase A, as well as the efficacy of several cytidine nucleotides as competitive inhibitors of catalysis. They showed that the most efficient inhibitor was cytidine 2′-phosphate, inferring that a specific interaction existed between the 2′-oxygen of the substrate and the enzyme, that the interaction with the 3′-oxygen likely occurred through a water molecule, and that a histidine residue was involved in these interactions.

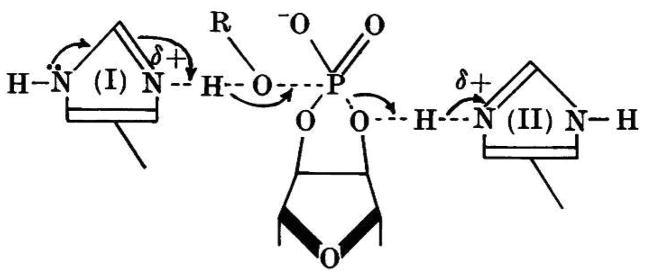

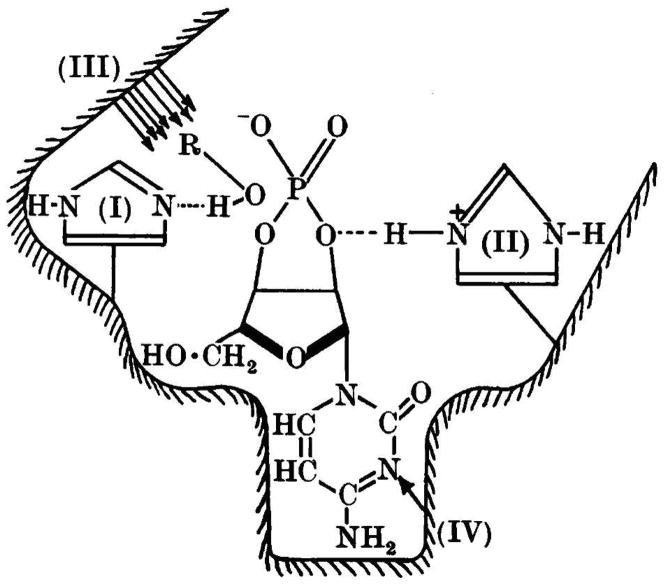

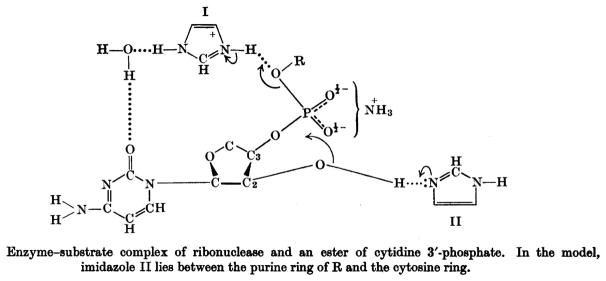

All of these facts were put together in the last paper of the series (6), in which a mechanism involving general acid–base catalysis promoted by two histidine residues was put forth. The path of the electrons and the transition state involved in the hydrolysis reaction is depicted in Fig. 4. In this representation, I is the imidazole that binds either water or alcohol, and II is the imidazolium ion that interacts with the 2′-oxygen atom of the substrate. The group of Mathias and Rabin also presented a model of the enzyme substrate complex (Fig. 5) in which I and II are the same imidazoles as in Fig. 4, III represents the sites of additional interaction with the alcohol, and IV is the specificity site in which N-1 of the pyrimidine nucleobase would seem to interact with the enzyme. A hydrogen bond between imidazolium ion II and O-2′ weakens the P–O2′ bond and renders the phosphorus more susceptible to nucleophilic attack; a hydrogen bond between imidazole I and a nucleophilic alcohol increases the nucleophilicity of its oxygen. The roles of I and II are reversed in the transphosphorylation reaction (Fig. 1, first step).

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of Mathias and Rabin for catalysis of the hydrolysis (R = H) of cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate by RNase A. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 2 of Findlay et al. (6).)

Fig. 5.

Model of the RNase A substrate complex. The substrate here is cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic cyclic phosphate. I and II are the imidazolyl groups of two histidine residues. III is an enzymic region that interacts with an alcohol or water. IV is the specificity region of the enzyme that interacts with the pyrimidine nucleobase of the substrate. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 1 of Findlay et al. (6).)

CRITICISMS AND ALTERNATIVE MECHANISMS

The Mathias and Rabin mechanism for catalysis by RNase A was, at the beginning, questioned in several respects. On the one hand, it was known that rate increases attainable by either general acid or general base catalysis could not alone explain the high catalytic efficiency of the enzyme. On the other, the pKa values obtained for the histidines (Fig. 2C) were somewhat divergent from that of imidazole, either free or in the side-chain of the amino acid. It should be noted that in 1961, the enormous increases in rate attainable from binding energy were not known (21). Neither were known the large perturbations to the pKa values of a functional group that can occur in an enzymic active site (22, 23).

Among the alternative mechanisms that have been put forward, those of Witzel (24), Wang (25), and Breslow (26) were the most relevant. In the Witzel mechanism, only one histidine was involved, the role of the other being taken by O-2 of the pyrimidine nucleobase. The Wang mechanism invoked a charge–relay system analogous to that of chymotrypsin; and in the mechanism proposed by Breslow, a phosphorane intermediate was involved, imposing a second transition state on the path from substrate to product.

SUPPORT FOR THE MATHIAS AND RABIN MECHANISM

Several lines of evidence provided support to the mechanism of Mathias and Rabin. Experiments with haloacetic acids confirmed the important role of both His12 and His119 (27, 28), and although the pKa values so obtained were somewhat different from those obtained by kinetic studies, they were close enough to identify them as the groups involved in general acid– base catalysis. The high-resolution three-dimensional structure of RNase S (11) showed that histidines 12 and 119 were at the right distance to interact in a manner consistent with the proposed transition state (Fig. 4). In contrast, O-2 of the pyrimidine nucleobase was too distal to interact with the substrate. Experiments with 1H NMR spectroscopy (12) were also in agreement with the Mathias and Rabin mechanism. The studies on the stereospecificity of the reaction carried out by Eckstein and coworkers (29), using chiral phosphorothioate analogues of the substrate, demonstrated that the reaction followed an in-line mechanism as opposed to an adjacent one. These conditions were fulfilled by the Mathias and Rabin mechanism and not by that of Witzel. Further confirmation came from molecular dynamics studies by Deakyne and Allen (30) that could only be explained in terms of the proposed mechanism. Finally, studies using recombinant DNA technology to create variants at His12 and His119 (31–33) and measuring heavy-atom isotope effects on catalysis (34, 35) were in full accord with a concerted mechanism that employs these residues in general acid–base catalysis.

REFINEMENTS OF THE MECHANISM

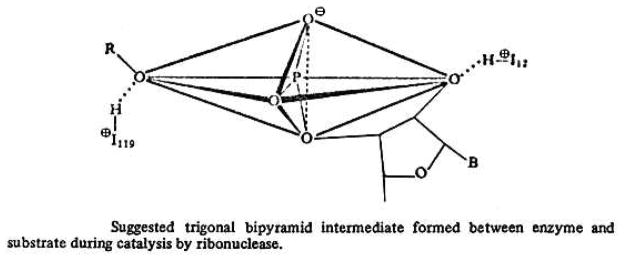

In 1966, the same team of Mathias and Rabin provided a more refined structure of the transition state (36). An additional cationic acid, such as the ammonium group in the side chain of a lysine residue, was proposed to stabilize the negative charge on the non-bridging oxygens of the phosphoryl group (Fig. 6), an aspect confirmed in 1995 by site-directed mutagenesis (37). Later (38), they applied the criteria established in phosphorus chemistry (39) and postulated that the transition state was a trigonal bipyramid (Fig. 7). NMR spectroscopy enabled the precise determination of the pKa values of the four histidine residues in RNase A, and showed that the pKa values of His12 and His119, both in the free enzyme and in the presence of a substrate analogue, were in agreement with the data obtained with kinetic methods (40). Eventually, the pKa values assigned initially to His12 and His119 had to be exchanged (41, 42). Nonetheless, this reassignment had no effect on the rationale for the catalytic mechanism.

Fig. 6.

Refined model of the RNase A substrate complex showing the interaction of an ammonium group with non-bridging oxygens of the phosphoryl group. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 1 of Deavin et al. (36).)

Fig. 7.

Trigonal bipyramid formed during catalysis by RNase A. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 12 of Rabin et al. (38 ).)

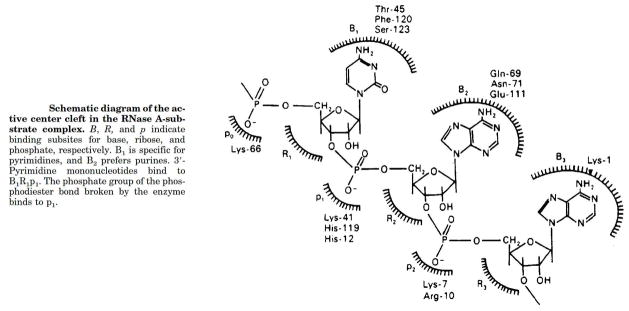

One of us (C.M.C.) started to work with Tony Mathias and Bob Rabin at University College London in 1966. The goal was to determine the identity of the residues in region III (Fig. 5), as it was known that the type of nucleobase (R in Fig. 5) had an important effect on the rate of catalysis for RNA cleavage. For example, the cleavage rate for substrates of the type NpN′, where N is a pyrimidine, was known to depend on N′ and to decrease in the order: A > G > C > U (43). The electrophile 6-chloropurine was used to label region III, and led to the identification of several enzymic amino groups proximal to the active site (38). A more elaborate affinity label, the 5′-nucleotide of 6-chloropurine, reacted specifically with the á-amino group of Lys1 (44). Stereochemical and other considerations allowed us to postulate the presence of a secondary site (p2) that bound the phosphoryl group on the 3′ side of the scissile bond. Similarly, other subsites were postulated, and eventually some of them were assigned to distinct residues in RNase A (45). Thus, a great deal of information is now available about region III in Fig. 5. A scheme of the amino-acid residues involved in each subsite is shown in Fig. 8. A fourth phosphate-binding subsite was identified in 1998 (46). In assays at low salt concentration, the favorable Coulombic interactions engendered by these phosphate-binding subsites leads to a second-order rate constant (kcat/KM = 2.7 × 109 M−1s−1 (47)) that is among the largest in enzymology.

Fig. 8.

Subsites of RNase A. Bn, Rn, and pn are nucleobase-, ribose-, and phosphate-binding subsites, respectively, and are shown with their constituent residues. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 1 of Moussaoui et al. (48).)

Studies on the RNase A subsites have provided insight on the unusual kinetic behavior for the turnover of either the mononucleotide cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate at very high concentrations or cytidine oligonucleotides of various lengths (48). They have also provided an explanation for the exo- and endonucleolytic activities of RNase A with poly(C) as substrate (49). Finally, it has been possible to construct an alternative active site by replacing the constituent amino acids (Lys7 and Arg8) of the p2 subsite with two histidines that act as do His12 and His119 of the original active site located in the p1 subsite (50).

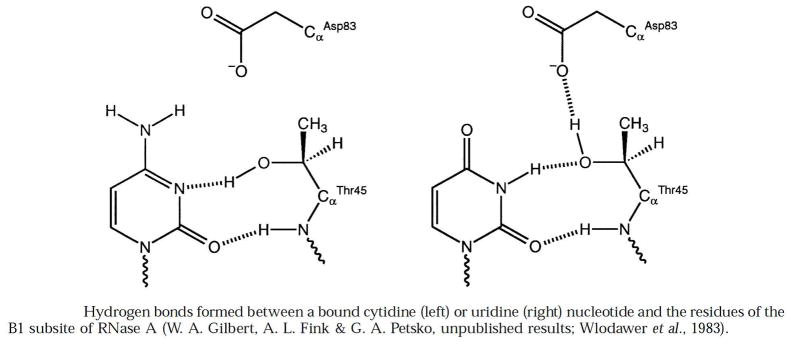

In region IV of Fig. 5, the side-chain hydroxyl and main-chain carbonyl groups of Thr45 mediate the specificity of RNase A by forming hydrogen bonds with a pyrimidine nucleobase and excluding a purine nucleobase (51). Asp83 also affects the uridilyl specificity of the enzyme through an interaction that relies on the side chain of Thr45 forming a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asp83 (Fig. 9). The space created by replacing Thr45 with a smaller alanine or glycine residue enables RNase A to cleave poly(A) efficiently and processively (52).

Fig. 9.

Hydrogen bonds formed by pyrimidine nucleobases and residues in the B1 subsite of RNase A. (Reproduced with permission from Fig. 3 of delCardayré and Raines (51).)

A final aspect of the enzymatic reaction is now clear. The traditional depiction has the reaction of RNase A taking place in two steps—transphosphorylation with the formation of a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate followed by hydrolysis of the cyclic nucleotide to a 3′-nucleotide (Fig. 1). Do the two reactions take place sequentially, with the intermediate 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate remaining bound to the enzyme? We showed, separately (53, 54), that this depiction is incorrect—RNase A is actually an “RNA depolymerase” (55). For example, during the breakdown of poly(C) by RNase A, 2′,3′-cyclic phosphates of a progressively lower molecular mass accumulate in the medium and undergo hydrolysis only when no susceptible phosphodiester bonds remain intact (53). These accumulating intermediates are readily apparent with 31P NMR spectroscopy (54). The hydrolysis step, which is much slower than the transphosphorylation step, is essentially the microscopic reverse of the transphosphorylation step in which R in Fig. 5 is simply a hydrogen atom. This added precision does not contravene the mechanism of Mathias and Rabin, as they had considered that the reactions could be treated as the reverse of each other and that the histidine residues took on opposite roles in each reaction (6). After each catalytic cycle, the proper form—protonated or unprotonated—of His12 and His119 has to be reset, probably through rapid proton-exchange reactions mediated by water or buffer ions.

CONTRIBUTION OF THE MECHANISM TO BIOCHEMISTRY

The mechanism that we have been discussing is, at present, acknowledged as the one that fits the known data on RNase A most faithfully. Inevitably, more details will be reported, but these will not affect the basis of the mechanism. They will only add precision to what is accepted as an accurate picture on how RNase A modifies its RNA substrate. The importance of this mechanism can be seen in the number of general reviews that have been published regularly on RNase A and that consider it to be the most plausible. Among them we can mention those of Richards and Wyckoff in 1971 (15), Blackburn and Moore in 1982 (56), Eftink and Biltonin in 1987 (57), Lolis and Petsko in 1990 (58), D’Alessio and Riordan in 1997 (59), and Raines in 1998 (60). Several specialized books on enzymology also include this mechanism (61–65). In addition, we note that the mechanism has been depicted in many of the most influential textbooks of biochemistry (66–70).

To sum up, the first catalytic mechanism of an enzyme was deduced 50 years ago by an extraordinary integration of attainable knowledge about enzymology and protein chemistry (1). This mechanism is accepted widely today. On this notable anniversary,2 we want to pay due homage to Tony Mathias, Bob Rabin, and their coworkers, who contributed so consequentially to the field of mechanistic enzymology.

Footnotes

Work by the authors on ribonucleases has been supported by generous grants from the Direcció General de Recerca of the Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR2009-795), Dirección General de Investigación of the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain) (BFU2009-09731), and the National Institutes of Health (USA) (R01 CA073808).

Abbreviations: poly(A), poly(adenylic acid); poly(C), poly(cytidylic acid); RNase, ribonuclease.

We note that the deduction of the first enzymatic reaction mechanism in 1961 coincides with the founding of the journal Biochemistry.

The kcat/KM curve (●) in Fig. 2A has become a canonical “bell-shaped” pH–rate profile.

References

- 1.Findlay D, Herries DG, Mathias AP, Rabin BR, Ross CA. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. Nature. 1961;190:781–784. doi: 10.1038/190781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herries DG, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. 3. The pH-dependence of the kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of cytidine 2′,3′-phosphate. Biochem J. 1962;85:127–134. doi: 10.1042/bj0850127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findlay D, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. 4. The activity in inert organic solvents and alcohols. Biochem J. 1962;85:134–139. doi: 10.1042/bj0850134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Findlay D, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. 5. The charge types at the active centre. Biochem J. 1962;85:139–144. doi: 10.1042/bj0850139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross CA, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. 6. Kinetic and spectrophotometric investigation of the interaction of the enzyme with inhibitors and p-nitrophenyl acetate. Biochem J. 1962;85:145–151. doi: 10.1042/bj0850145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Findlay D, Herries DG, Mathias AP, Rabin BR, Ross CA. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. 7. The catalytic mechanism. Biochem J. 1962;85:152–153. doi: 10.1042/bj0850152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender ML. The mechanism of á-chymotrypsin-catalyzed hydrolyses. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:2582–2590. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake CCF, Johnson LN, Mair GA, North ACT, Phillips DC, Sarma VR. Crystallographic studies of the activity of hen egg-white lysozyme. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1967;167:378–388. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1967.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smyth DG, Stein WH, Moore S. The sequence of amino acid residues in bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Revisions and confirmations. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kartha G, Bello J, Harker D. Tertiary structure of ribonuclease. Nature. 1967;213:862–865. doi: 10.1038/213862a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyckoff HW, Hardman KD, Allewell NM, Inagami T, Johnson LN, Richards FM. The structure of ribonuclease-S at 3.5 Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:3984–3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts GCK, Dennis EA, Meadows DH, Cohen JS, Jardetzky O. The mechanism of action of ribonuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;62:1151–1158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunitz M. Isolation from beef pancreas of a crystalline protein possessing ribonuclease activity. Science. 1939;90:112–113. doi: 10.1126/science.90.2327.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards FM. Linderstrøm-Lang and the Carlsberg Laboratory: The view of a postdoctoral fellow in 1954. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1721–1730. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards FM, Wyckoff HW. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. The Enzymes IV. 1971:647–806. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markham R, Smith JD. The structure of ribonucleic acids. 1. Cyclic nucleotides produced by ribonuclease and by alkaline hydrolysis. Biochem J. 1952;52:552–557. doi: 10.1042/bj0520552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crook EM, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The preparation and purification of cytidine 2′:3′-cyclic phosphate. Biochem J. 1960;74:230–233. doi: 10.1042/bj0740230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crook EM, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. Spectrophotometric assay of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease by the use of cytidine 2′:3′-phosphate. Biochem J. 1960;74:234–238. doi: 10.1042/bj0740234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnard EA, Stein WD. The histidine in the active centre of ribonuclease. I. A specific reaction with bromoacetic acid. J Mol Biol. 1959;1:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rushizky GW, Knight CA, Sober HA. Studies on the preferential specificity of pancreatic ribonuclease as deduced from partial digests. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:2732–2737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page MI, Jencks WP. Entropic contributions to rate accelerations in enzymic and intramolecular reactions and the chelate effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:1678–1683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey PA, Kokesh FC, Westheimer FH. A reporter group at the active site of acetoacetate decarboxylase. I. Ionization constant of the nitrophenol. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:7266–7269. doi: 10.1021/ja00755a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokesh FC, Westheimer FH. A reporter group at the active site of acetoacetate decarboxylase. II. Ionization constant of the amino group. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:7270–7274. doi: 10.1021/ja00755a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witzel H. The function of the pyrimidine base in the ribonuclease reaction. Progr Nucleic Acid Res. 1963;2:221–258. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JH. Facilitated proton transfer in enzyme catalysis. Science. 1968;161:328–334. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3839.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anslyn E, Breslow R. On the mechanism of catalysis by ribonuclease: Cleavage and isomerization of the dinucleotide UpU catalyzed by imidazole buffers. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4473–4482. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamden MP, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. The inhibition of ribonuclease by iodoacetate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1962;8:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crestfield AM, Stein WH, Moore S. Alkylation and identification of the histidine residues at the active site of ribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:2413–2420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usher DA, Richardson DI, Jr, Eckstein F. Absolute stereochemistry of the second step of ribonuclease action. Nature. 1970;228:663–665. doi: 10.1038/228663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deakyne CA, Allen LC. Role of active-site residues in the catalytic mechanism of ribonuclease A. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:3951–3959. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson DY, Burnier J, Quan C, Stanley M, Tom J, Wells JA. A designed peptide ligase for total synthesis of ribonuclease A with unnatural catalytic residues. Science. 1994;266:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7939659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson JE, Raines RT. Value of general acid–base catalysis to ribonuclease A. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5467–5468. doi: 10.1021/ja00091a060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park C, Schultz LW, Raines RT. Contribution of the active site histidine residues of ribonuclease A to nucleic acid binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4949–4956. doi: 10.1021/bi0100182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sowa GA, Hengge AC, Cleland WW. 18O isotope effects support a concerted mechanism for ribonuclease A. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2319–2320. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hengge AC, Bruzik KS, Tobin AE, Cleland WW, Tsai MD. Kinetic isotope effects and stereochemical studies on a ribonuclease model: Hydrolysis reactions of uridine 3′-nitrophenyl phosphate. Bioorg Chem. 2000;28:119–133. doi: 10.1006/bioo.2000.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deavin A, Mathias AP, Rabin BR. Mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. Biochem J. 1966;101:14c–16c. doi: 10.1042/bj1010014c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messmore JM, Fuchs DN, Raines RT. Ribonuclease A: Revealing structure–function relationships with semisynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8057–8060. doi: 10.1021/ja00136a001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabin BR, Cuchillo CM, Deavin A, Kemp CM. FEBS Symposium. Vol. 19. Academic Press; New York: 1969. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Substrate binding and mechanism of action; pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennis EA, Westheimer FH. The rates of hydrolysis of esters of cyclic phosphinic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3431–3432. doi: 10.1021/ja00966a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meadows DH, Jardetzky O, Epand RM, Rüterjans HH, Scheraga HA. Assignment of the histidine peaks in the nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of ribonuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;60:766–772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.60.3.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradbury JH, Teh JS. Reassignment of the histidine 1H nuclear magnetic resonances of ribonuclease-A. Chem Commun. 1975:936–937. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markley JL. Correlation proton magnetic resonance studies at 250 MHz of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. I. Reinvestigation of the histidine peak assignment. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3546–3553. doi: 10.1021/bi00687a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witzel H, Barnard EA. Mechanism and binding sites in the ribonuclease reaction II. Kinetic studies of the first step of the reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 1962;7:295–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parés X, de Llorens R, Arús C, Cuchillo CM. The reaction of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A with 6-chloropurineriboside 5′-monophosphate. Eur J Biochem. 1980;105:571–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuchillo CM, Vilanova M, Nogués MV. Pancreatic ribonucleases. In: D’Alessio G, Riordan JF, editors. Ribonucleases: Structures and Functions. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 271–304. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher BM, Grilley JE, Raines RT. A new remote subsite in ribonuclease A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34134–34138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park C, Raines RT. Quantitative analysis of the effect of salt concentration on enzymatic catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11472–11479. doi: 10.1021/ja0164834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moussaoui M, Nogués MV, Guasch A, Barman T, Travers F, Cuchillo CM. The subsites structure of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A accounts for the abnormal kinetic behavior with cytidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25565–25572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuchillo CM, Moussaoui M, Barman T, Travers F, Nogués MV. The exo- or endonucleolytic preference of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A depends on its subsites structure and on the substrate size. Protein Sci. 2002;11:117–128. doi: 10.1110/ps.13702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moussaoui M, Cuchillo CM, Nogués MV. A phosphate-binding subsite in bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A can be converted into a very efficient catalytic site. Protein Sci. 2007;16:99–109. doi: 10.1110/ps.062251707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.del Cardayré SB, Raines RT. A residue to residue hydrogen bond mediates the nucleotide specificity of ribonuclease A. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:328–336. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.delCardayré SB, Raines RT. Structural determinants of enzymatic processivity. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6031–6037. doi: 10.1021/bi00186a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cuchillo CM, Parés X, Guasch A, Barman T, Travers F, Nogués MV. The role of 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesters in the bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A catalysed cleavage of RNA: Intermediates or products? FEBS Lett. 1993;333:207–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80654-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson JE, Venegas FD, Raines RT. Energetics of catalysis by ribonucleases: Fate of the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester intermediate. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7408–7414. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnard EA. Ribonucleases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1969;38:677–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.38.070169.003333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blackburn P, Moore S. Pancreatic ribonuclease. The Enzymes XV. 1982:317–433. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eftink MR, Biltonen RL. Pancreatic ribonuclease A: The most studied endoribonuclease. In: Neuberger A, Brocklehurst K, editors. Hydrolytic Enzymes. Elsevier; New York: 1987. pp. 333–375. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lolis E, Petsko GA. Transition state analogues in protein crystallography: Probes of the structural source of enzyme catalysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:597–630. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D’Alessio G, Riordan JF, editors. Ribonucleases: Structures and Functions. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1045–1065. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernhard S. The Structure and Function of Enzymes. W. A. Benjamin; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fersht A. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. 2. W. H. Freeman; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walsh C. Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms. W. H. Freeman and Company; San Francisco: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. W. H. Freeman; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frey PA, Hegeman A. Enzymatic Reaction Mechanisms. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metzler DE. Biochemistry The Chemical Reactions of Living Cells. Academic Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rawn JD. Biochemistry. Neil Patterson Publishers; Burlington, VT: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stryer L. Biochemistry. 4. Freeman; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devlin TM. Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. 5. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 3. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]