Abstract

Objectives: In a pilot study, the library had good results using SERVQUAL, a respected and often-used instrument for measuring customer satisfaction. The SERVQUAL instrument itself, however, received some serious and well-founded criticism from the respondents to our survey. The purpose of this study was to test the comparability of the results of SERVQUAL with a revised and shortened instrument modeled on SERVQUAL. The revised instrument, the Assessment of Customer Service in Academic Health Care Libraries (ACSAHL), was designed to better assess customer service in academic health care libraries.

Methods: Surveys were sent to clients who had used the document delivery services at three academic medical libraries in Texas over the previous twelve to eighteen months. ACSAHL surveys were sent exclusively to clients at University of Texas (UT) Southwestern, while the client pools at the two other institutions were randomly divided and provided either SERVQUAL or ACSAHL surveys.

Results: Results indicated that more respondents preferred the shorter ACSAHL instrument to the longer and more complex SERVQUAL instrument. Also, comparing the scores from both surveys indicated that ACSAHL elicited comparable results.

Conclusions: ACSAHL appears to measure the same type of data in similar settings, but additional testing is recommended both to confirm the survey's results through data replication and to investigate whether the instrument applies to different service areas.

INTRODUCTION

Libraries are competing with many commercial and noncommercial services to provide access to medical information. In a highly competitive environment, providing excellent, personalized service can be a relatively low-cost way of gaining a competitive advantage. For this reason, among others, many libraries are paying more attention to customer service.

While libraries have traditionally been evaluated using tangible indicators such as size and quality of their collections, customer satisfaction as a measure of quality is relatively unfamiliar. Libraries have had tools to assist them in decision making on the basis of these tangible measures, but, in contrast to the retail and commercial service industries, there have been few sophisticated tools developed for libraries to monitor and measure customer satisfaction and customer service delivery. One tool that has been used, however, is the SERVQUAL customer service instrument.

This study relates the authors' experiences with using SERVQUAL in an academic medical library setting and compares those results with the ones obtained with our own revised and shortened version of the instrument. Results are presented for three academic institutions in the state of Texas.

BACKGROUND

The original SERVQUAL was the work of Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry, and is built upon the Gaps Model of service quality [1]. This model claims that customer satisfaction can be understood as and measured by a series of gaps between expectations and perceptions. In SERVQUAL, service quality is divided into five distinct dimensions:

Tangibles: the physical environment where the service personnel work (e.g., the general office layout, the general state and appearance of equipment, etc.)

Reliability: the accuracy of the information that service personnel deliver

Responsiveness: the timeliness of information provided by service personnel

Assurance: the level of competence service personnel exhibit

Empathy: the emotional demeanor of service personnel (e.g., personnel politeness, helpfulness, etc.)

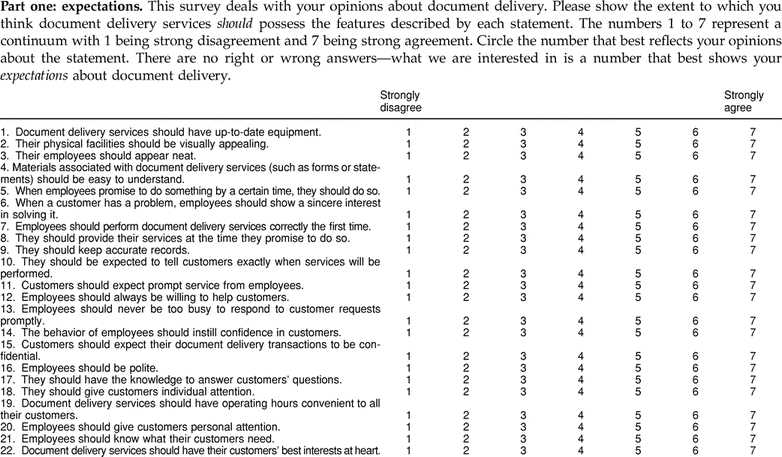

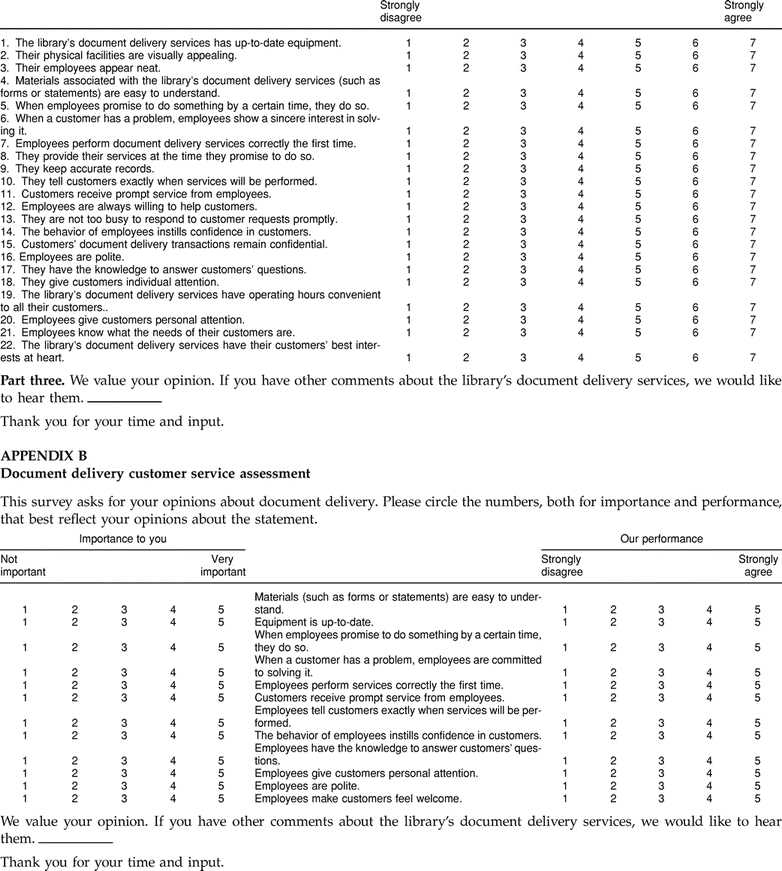

The survey instrument as designed by Parasuraman et al. is divided into an “expectations” section, which rates the level of service customers expect, and a “perceptions” section, which rates how customers perceive the existing service [2]. The statements in each of the two sections differ only in verb tense. For example, the statement “Document delivery services should have up-to-date equipment” appears in the expectations section; however, in the perceptions section, the statement is rendered as follows: “The library's document delivery services has up-to-date equipment” (Appendix A, parts 1 and 2). The customer-oriented definition of service quality, as measured by the discrepancy between the customer's expectations of the service and the perceptions of the delivered service, forms the conceptual basis for the instrument.

Some authors, most notably Cronin and Taylor, disagree about the usefulness of gap analysis and wish to concentrate only on the perception of service quality, in other words, the performance side of the equation [3]. In this same line of thinking, White and Abels suggest the use of another instrument, SERVPERF, which addresses the performance measure alone [4]. In spite of these theoretical controversies, SERVQUAL has been and continues to be widely used and reported extensively in the business literature.

Nitecki slightly revised the original SERVQUAL of Parasuraman et al., tested it carefully in a general academic library setting, and began publishing her results in 1995 [5–8]. Her work with the instrument prompted us to select it as the basis for our service quality pilot survey.

PILOT STUDY‡

The University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Library serves a population of approximately 16,000 faculty, staff, students, and residents from UT Southwestern and its affiliated hospitals. The library maintains a collection of more than 260,000 volumes and 1,800 current journal subscriptions.

In the fall of 1996, we used SERVQUAL to measure customer satisfaction with our document delivery services. The survey instrument was sent to all of the library's primary clients who had used our document delivery services during the previous year.

When we began to analyze the results of the pilot study, we found that our clients had given uniformly high scores (from an average of 5.29 to 5.66 on a seven-point scale) for how well they perceived we were doing. This high perception did not allow us to identify any single area where we were failing to provide above average customer service. Also, the instrument indicated our clients had very high expectation levels (averaging from 5.76 to 6.66) for all dimensions of service. These scores thus did not give us much useful information about areas to which we could devote less effort.

In an attempt to explain these discrepancies, we theorized that the highly specialized and dedicated scientists, physicians, and researchers in an academic medical center have uniformly high expectations of their colleagues and carry this over to their expectations of service from library staff. Such “artificially” high expectations would naturally produce distorted results in an instrument such as SERVQUAL, which depends on respondents differentiating between expectations in various dimensions of customer service.

Problems with the survey instrument

We received a number of negative comments from our respondents regarding both the length and the apparent redundancy of the survey, which presented twenty-two questions each for the expectations and perceptions sections with only slight differences in wording between the two sets. In fact, the majority of negative comments focused on these “survey problems” rather than on the document delivery service itself.

In an effort to respond to this criticism of the instrument, we used SERVQUAL as the basis for a modified survey instrument, which we named the Assessment of Customer Service in Academic Health Care Libraries (ACSAHL). We made the following changes when we constructed the modified instrument:

Structure: We reduced the base number of questions from twenty-two to twelve and arranged both measurement scales on the same page, which would allow busy clients to answer them more easily and quickly. Because standard deviation measured the uniformity of responses, we reasoned that those statements with the highest standard deviation scores were the most ambiguous in wording or were the most confusing to the respondents. Our respondents also singled out other specific statements that were redundant within the same section.

Measurement: We reduced the Likert scale from seven points to five. We thought that the seven-point scale used with SERVQUAL might confuse some respondents (i.e., they were unable to distinguish the expectations and perceptions to such a high degree).

Vocabulary: We altered the names of the two scales to better clarify what we were looking for without the need to include the extremely long and confusing instructions for each section (Appendix A). The changes were as follows:

“Importance” replaced “expectations,” because we thought the concept “how important is this service to you” was easier to understand than “how do you expect this service to be.”

“Performance” replaced “perceptions,” because we thought the concept “how did we perform” was clearer than “how did you perceive the service to be.”

By making these changes, we were able to reduce the entire survey instrument from three pages in length to approximately one-half of a page. The reduction in the length of the survey allowed room for surveyors to add additional questions, either task-specific or open-ended, and still keep the total length either under two pages or one page, front and back (Appendix B).

METHODOLOGY

Our research had two main objectives:

to determine whether the SERVQUAL instrument as previously tested in our library gave comparable results, especially with regard to its expectation scale, in other academic medical libraries

to test the comparability of the results of ACSAHL and SERVQUAL in the same setting

Two other academic medical libraries in Texas were asked to participate in the research project. Each library was asked to provide a list of names and addresses of document delivery clients during the previous twelve to eighteen months. The client list used in the SERVQUAL pilot study contained somewhat more than 500 names. Each cooperating institution provided a comparable number from their active client databases.

Because we had given SERVQUAL to our clients last year in the pilot study, we administered only the ACSAHL instrument to our own pool of document delivery clients. The client pool at each of the other institutions was divided at random into two groups: one received the SERVQUAL instrument, and the other received the ACSAHL instrument.

Postcard alerts were first mailed to all potential survey respondents approximately two weeks before the surveys, which allowed us to make an initial cleanup of incorrect or outdated addresses while alerting respondents to the survey's arrival. We also used the lists of names and addresses to print personalized cover letters to accompany the surveys.

Each survey carried a unique number that allowed us to track which surveys were returned to follow up with a second letter and survey for all nonrespondents. To preserve confidentiality, respondent information and the survey results were maintained in separate tables. Survey codes were the only common factors.

To ensure compatibility of results, the team at UT Southwestern prepared all correspondence, modifying the postcard and cover letter texts to conform to each institution's accepted guidelines for internal communications. The prepared correspondence was delivered to each of the other institutions—and each institution collected and returned the completed surveys to UT Southwestern—through courier services.

We then compiled and tabulated the survey results. Because the surveys did use two different Likert scales, we needed to convert the original ACSAHL scores to compare them more easily with the SERVQUAL results. We accomplished this by simply multiplying the original scores by a factor of 1.4 (i.e., the SERVQUAL point scale of 7 divided by the ACSAHL point scale of 5).

RESULTS

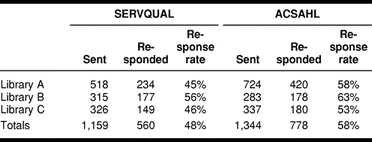

A combined total of 1,159 SERVQUAL surveys were mailed to library clients at all three participating institutions, and 560 were returned completed. Out of a total 1,344 ACSAHL surveys mailed, 778 were returned. Table 1 displays the response rates by library and survey for each participating institution. Overall, the ACSAHL survey had uniformly higher response rates than the SERVQUAL survey (an average of 58% versus 48%).

Table 1 SERVQUAL and Assessment of Customer Service in Academic Health Care Libraries (ACSAHL) response rates

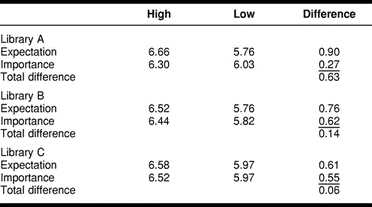

Table 2 illustrates the differentiation between the “expectation” scores from SERVQUAL and the “importance” scores from ACSAHL. The results for Library A show a greater difference (0.63) between the two measurement scales than the other two libraries. The scores for the other two libraries are relatively comparable (0.14 for Library B and 0.06 for Library C). These scores would seem to indicate that the two scales are collecting the same information.

Table 2 Differentiation on “expectation” (SERVQUAL) and “importance” (ACSAHL) attributes

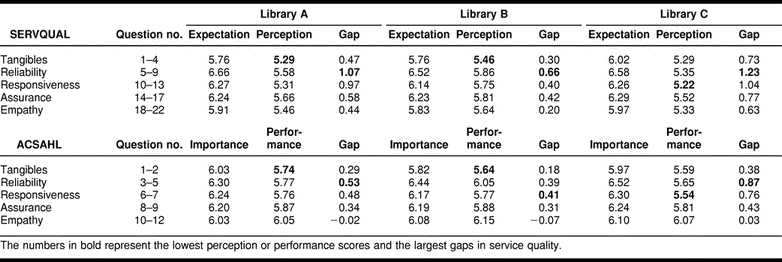

Table 3 presents both the grouping of the questions within each dimension as well as the averages of all survey scores across the five dimensions. The numbers in bold represent the lowest perception or performance scores and the largest gaps in service quality.

Table 3 Average scores on five dimensions of customer service

To calculate the averages, the scores for each question are added together and divided by the total number of responses. The question totals within each dimension are then added together and divided by the number of questions in each dimension on the survey instrument. For example, the totals for questions one through four in SERVQUAL are added together and divided by four to obtain the average for the Tangibles dimension.

For Library A, the SERVQUAL and ACSAHL results both indicate that the Tangibles dimension has the lowest perception or performance scores, and the greatest gap exists in the Reliability dimension. Library C's results show a similar correlation between the two instruments, where the Responsiveness dimension has the lowest perception or performance scores, and the Reliability dimension has the greatest gap.

However, Library B's results demonstrate that while the two instruments “agree” on the lowest perception or performance scores (Tangibles), the greatest gap appears in the Reliability dimension for SERVQUAL and in the Responsiveness dimension for ACSAHL.

DISCUSSION

As indicated above, we identified certain conditions in the results from the SERVQUAL pilot study (uniformly high perception and expectation scores) that made it difficult to clearly identify dimensions on which we could decrease attention or increase effort. Accordingly, we designed the ACSAHL instrument with the intent of correcting those conditions.

Structure

Many respondents to the SERVQUAL instrument, which was administered at the participating libraries, continued to complain about the survey's length and redundancy rather than commenting on those libraries' document delivery services. In contrast, far fewer negative comments were recorded on the ACSAHL instrument from all three libraries.

Also, the high response rates from all three participating libraries showed that clients at each library were very involved in using document delivery services and were concerned about maintaining the quality of those services. However, the ACSAHL response rates were substantially higher than SERVQUAL's.

Both of these factors indicated that ACSAHL respondents felt more comfortable navigating the revised instrument, with its fewer questions (12 questions compared to SERVQUAL's 22) and its simplified layout (both measurement scales on one page). This higher comfort level suggested that respondents focused less on the survey design and more on the particular questions, and, as a result, ACSAHL respondents felt more confident about expressing their true opinions.

Measurement

We initially felt that SERVQUAL's seven-point Likert scale was too detailed to measure customer satisfaction accurately. After examining the results, the five-point scale used in ACSAHL did show comparable scores (after being converted to a seven-point scale) to SERVQUAL's scores, but the gaps were substantially lower on all dimensions, suggesting that the reduced scale was not detailed enough to allow for sufficient discrimination between the importance and performances scores. Because discrimination is essential in determining the gap, we feel that future applications of ACSAHL may be better served by reapplying the seven-point scale.

Vocabulary

We hypothesized that SERVQUAL's “expectations of service” and “perceptions of service” scales were too ambiguous and required too much explanation to understand. We also thought that some respondents might have overlooked the directions simply because of the length. Therefore, ACSAHL was designed with an “Importance” scale and a “Performance” scale, which we believed would better communicate the values we wanted to measure without detailed explanations.

Comparing the results, we can see that the same data are being gathered by both surveys. While this does not initially show a preference for either scale classification scheme, we still feel that the “importance” and “performance” headings are slightly more intuitive to understand, based on both the higher response rates and the fewer negative comments.

It is also interesting to note that Cronin and Taylor state that it is more important to focus on the perception scores of service quality [9] when measuring customer satisfaction. Clearly, different service dimensions would warrant a higher priority for intervention if the lowest perception or performance scores receive more attention than the largest gap in both instruments. However, while the ACSAHL gaps do identify problem areas, we have some questions as to how well ACSAHL discriminates in determining the gaps, because the gaps are consistently lower overall compared to the SERVQUAL gaps.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of our study was to determine if both the SERVQUAL and ACSAHL instruments recorded comparable results in similar settings. For two out of the three participating libraries, both instruments revealed the same “problem” areas in both the lower perception or performance scores and in the gap analysis. From our very limited testing, we believe that ACSAHL does measure the same quality of service as SERVQUAL and can be applied in related settings. Also, the higher response rates and fewer negative comments for ACSAHL indicate that survey respondents prefer a shorter survey instrument (about one page) to a much longer one.

However, the lower gap scores in the ACSAHL instrument do suggest that additional research needs to be done to verify its results. Some possible avenues include replicating the survey methodology in the same service area to confirm the results, restoring the seven-point Likert scale to increase the level of discrimination and to see if the results are more consistent with SERVQUAL, and using the survey to measure customer satisfaction in another service area entirely.

APPENDIX A Document delivery customer survey

Part two: perceptions. The following set of statements relate to your opinions about the UT Southwestern library's document delivery services. For each statement, please show the extent to which you think the library's document delivery services has the feature described by the statement. Once again, the numbers 1 to 7 represent a continuum with 1 being strong disagreement and 7 being strong agreement. Circle the number that best reflects your opinions about the statement. There are no right or wrong answers—all we are interested in is a number that best shows your perceptions about the library's document delivery services

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the South Central Academic Medical Libraries Consortium Research Committee and would like to thank Kathryn Connell of the UT Southwestern Medical Center Library for her assistance with this project as well as her involvement in the SERVQUAL pilot study. We also express our appreciation to Martha Adamson, Dottie Eakin, and Virginia Bowden for permitting us to survey their libraries' document delivery services. We also thank Barbara Guidry, Nancy Burford, and the document delivery staff at the Texas A&M University Medical Sciences Library as well as Elizabeth Anne Comeaux and the document delivery staff at the Briscoe Library at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for their assistance in completing this project. And lastly, we thank Louella V. Wetherbee for introducing us to the SERVQUAL concept.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by a grant from the South Central Academic Medical Libraries (SCAMeL).

† Based on a presentation at the Ninety-ninth Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association, Chicago, Illinois; May 14–20, 1999.

‡ The results of this study were presented at the Ninety-eighth Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; May 22–27, 1998.

REFERENCES

- Parasuraman A, Zeithmal VA, and Berry LL. SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retailing. 1988 Spring; 64(1):12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A, Zeithmal VA, and Berry LL. SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retailing. 1988 Spring; 64(1):16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin JJ, Taylor SA. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J Market. 1992 Jul; 56(3):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- White MD, Abels EG. Measuring service quality in special libraries: lessons from service marketing. Spec Libr. 1995 Winter; 86(1):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki DA. An assessment of the applicability of SERVQUAL dimensions as customer-based criteria for evaluating quality of services in an academic library. [dissertation]. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland, 1995 263. [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki DA. An assessment of the applicability of SERVQUAL dimensions as customer-based criteria for evaluating quality of services in an academic library. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki DA. User expectations for quality library services identified through application of the SERVQUAL scale in an academic library. In: Continuity & transformation: the promise of confluence: proceedings of the seventh national conference of the Association of College and Research Libraries, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, March 29–April 1, 1995. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries, 1995 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki DA. Changing the concept and measure of service quality in academic libraries. J Acad Libr. 1996 May; 22(3):181–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin JJ, Taylor SA. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J Market. 1992 Jul; 56(3):64–65. [Google Scholar]