Abstract

We have identified a developmentally regulated, putative MEK kinase (MEKKα) that contains an F-box and WD40 repeats and plays a complex role in regulating cell-type differentiation and spatial patterning. Cells deficient in MEKKα develop precociously and exhibit abnormal cell-type patterning with an increase in one of the prestalk compartments (pstO), a concomitant reduction in the prespore domain, and a loss of the sharp compartment boundaries, resulting in overlapping prestalk and prespore domains. Overexpression of MEKKα or MEKKα lacking the WD40 repeats results in very delayed development and a severe loss of compartment boundaries. Prespore and prestalk cells are interspersed throughout the slug. Analysis of chimeric organisms suggests that MEKKα function is required for the proper induction and maintenance of prespore cell differentiation. We show that the WD40 repeats target MEKKα to the cortical region of the cell, whereas the F-box/WD40 repeats direct ubiquitin-mediated MEKKα degradation. We identify a UBC and a UBP (ubiquitin hydrolase) that interact with the F-box/WD40 repeats. Our findings indicate that cells lacking the ubiquitin hydrolase have phenotypes similar to those of MEKKα null (mekkα−) cells, further supporting a direct genetic and biochemical interaction between MEKKα, the UBC, and the UBP. We demonstrate that UBC and UBP differentially control MEKKα ubiquitination/deubiquitination and degradation through the F-box/WD40 repeats in a cell-type-specific and temporally regulated manner. Our results represent a novel mechanism that includes targeted protein degradation by which MAP kinase cascade components can be controlled. More importantly, our findings suggest a new paradigm of spatial and temporal control of the kinase activity controlling spatial patterning during multicellular development, which parallels the temporally regulated degradation of proteins required for cell-cycle progression.

Keywords: Dictyostelium, MEK kinase, ubiquitination, WD40 repeats, F-box, development

In Dictyostelium, multicellular development is initiated by the chemotactic aggregation of up to 105 cells to form a fruiting body containing a sorus of spores on a slender stalk held up by a basal disk (Loomis 1982). Aggregation is regulated through nanomolar cAMP pulses acting via pathways controlled through G protein-coupled, serpentine cell-surface receptors (cARs; Firtel 1995; Chen et al. 1996). As the mound forms, an increase in the level of extracellular cAMP is thought to activate a second signaling pathway that results in the induction of the postaggregative genes, including the transcription factor GBF and a transcriptional cascade that leads to cell-type differentiation (Abe et al. 1994; Schnitzler et al. 1994, 1995; Early et al. 1995; Firtel 1995, 1996; Ginsburg et al. 1995; Williams 1995). The newly formed prestalk and prespore cells then sort, producing a multicellular organism with a defined spatial pattern organized along the anterior-posterior axis.

A major question in developmental biology is how cells control their position and developmental state within a multicellular organism. Dictyostelium is an excellent system in which to examine this question, as cells do not become fully committed until culmination, when the fruiting body is formed. Wild-type Dictyostelium organisms can vary in size by >3 orders of magnitude, yet the spatial patterning of the cell types remains constant (Loomis 1993; Firtel 1995; Williams 1995). Recently, a number of genes have been shown to play important roles in controlling cell-type proportioning and spatial patterning in Dictyostelium. The homeobox-containing gene Wariai functions to control the respective sizes of the pstO and prespore domains via a cell nonautonomous pathway (Han and Firtel 1998). Disruption of Wariai leads to a more than doubling of the pstO compartment, with a concomitant decrease in the prespore domain. Null mutants in the cAMP receptor cAR4, which is expressed during multicellular development, or the RING-finger/leucine zipper adaptor protein result in an increase in prespore gene expression and abnormal spatial patterning. Overexpression of rZIP leads to enhanced prestalk expression and reduced prespore expression (Balint-Kurti et al. 1997; Ginsburg and Kimmel 1997). cAR4 is thought to function by negatively regulating GSK3 activity, which is required for prespore cell differentiation, and functions antagonistically on pathways controlled by cAR1 and cAR3, positive regulators of GSK3 (Harwood et al. 1995; Ginsburg and Kimmel 1997). A Dictyostelium STAT protein, Dd-STAT, regulates the spatial pattern of expression of the prestalk/stalk-specific gene ecmB and the differentiation of prestalk to stalk cells during culmination (Kawata et al. 1997; Araki et al. 1998; S. Mohanty, K.A. Jermyn, A. Early, A. Ceccarelli, T. Kawata, J.G. Williams, and R.A. Firtel, in prep.).

In this paper, we describe a new regulatory pathway including MEKKα that controls developmental timing and spatial patterning. We show that MEKKα is essential for pstO and prespore patterning: mekkα null cells or cells overexpressing a dominant-negative form of MEKKα develop rapidly, exhibit increased pstO and decreased prespore domains, and have a propensity to become prestalk cells in chimeras with wild-type cells. Overexpression of MEKKα or MEKKα lacking the WD40 repeats results in very delayed development and a loss of the discrete cell-type compartments. The F-box and WD40 repeats of MEKKα control the subcellular localization and a cell-type-specific and temporally regulated degradation via differential ubiquitination by a developmentally regulated UBP and a UBC. The spatial and temporal regulation of the stability of a MEKK represents a novel mechanism by which F-boxes and components of the ubiquitination pathway can function to control spatial patterning and developmental timing, the latter of which may have direct parallels to the regulation of cell-cycle components.

Results

Cloning and primary structure of the MEKKα

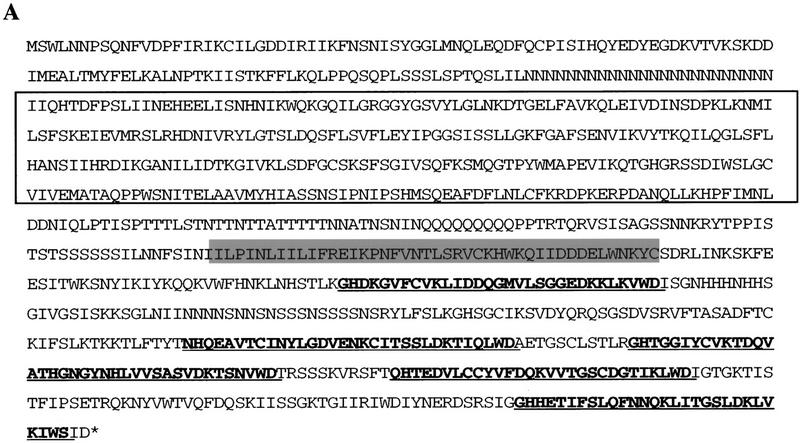

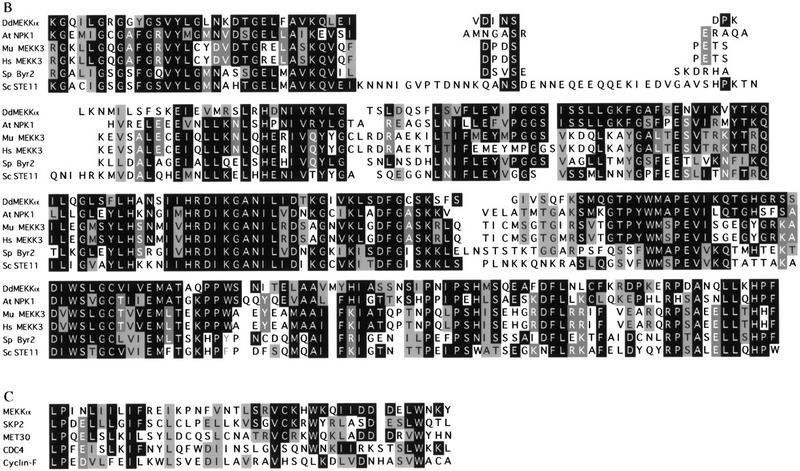

MEKKα was identified in a PCR screen for MEKKs. Using one of the PCR products as a probe, a cDNA library was screened and cDNA clones were isolated and sequenced. Analysis of the derived amino acid sequence of a full-length cDNA clone revealed that the gene encodes a putative MEKK (MEK kinase) designated MEKKα (Fig. 1A) with very high sequence homology to MEKKs from vertebrates, yeast, and plants (Fig. 1B). MEKKα has a short amino-terminal, potential regulatory domain. In addition, MEKKα has a carboxy-terminal domain containing a conserved F-box (Fig. 1C) with five WD40 repeats that are most related to those of MET30 (Thomas et al. 1995). The F-box, originally identified in yeast cyclin F and other cell-cycle regulating proteins (Bai et al. 1996), is thought to play an important role in regulating protein stability by targeting the protein for degradation via ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.

Figure 1.

Deduced sequence of MEKKα. (A) The cDNA clone, MEKKα 3-1, has an insert of 2922 nucleotides and contains the entire MEKKα ORF. The boxed region shows the conserved kinase domain. The hatched region (residues 523–563) shows the F-box sequence. The bold and underlined sequences indicate the position of five predicted β-transducin (WD40) repeats. (B) Amino acid sequence comparison of the kinase domain of MEKKα with MEKKs from a variety of organisms. Arabidopsis thaliana NPK1 (A48084); murine MEKK3 (U43187); human MEKK3 (U78876); Schizosaccharomyces pombe Byr2 (P28829); Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE11 (X53431); (C) Comparison of F-box sequence of MEKKα with the F-box sequences of other proteins such as human Cyclin F, human Skp2, Saccharomyces cerevisiae MET30, and CDC4.

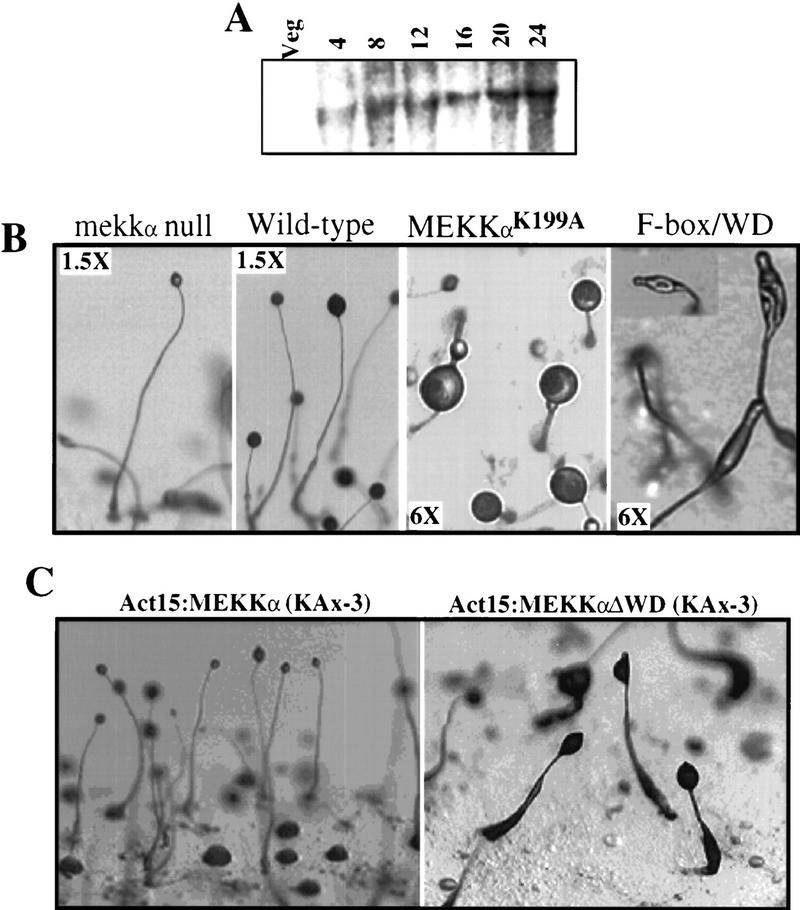

RNA blot analysis indicates that MEKKα encodes a single developmentally regulated transcript (3.7 kb) that is not detectable in vegetative cells and is induced during early development, with the highest expression during the multicellular stages (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the expression of the MEKKα gene during growth and development and the phenotype of MEKKα mutants. (A) Developmental RNA blot of MEKKα expression. Time in development is shown. (Veg) Vegetative cells. (B) Terminal phenotypes of mekkα− and wild-type cells and cells overexpressing the F-box/WD40 or MEKKαK199A. The values in the boxes are magnifications. mekkα− cells produce mature fruiting bodies that have smaller sori and longer stalks than mature wild-type fruiting bodies. Time of photographs: wild-type cells, 26 hr; mekkα− cells, 18 hr; MEKKαK199A-expressing cells, 36 hr (fruiting body formed at 18 hr, photograph shows glassy sori); cells overexpressing F-box/WD40 repeats, 36 hr. (C) Developmental morphology of cells overexpressing Act15/MEKKα or Act15/MEKKαΔ, which lacks WD40 repeats. Both MEKKα and MEKKαΔWD overexpression cause very delayed development and many of the cells are arrested at the mound stage as seen in the MEKKαOE image. The mature fruiting bodies have smaller sori than wild type. Photographs taken at 36 hr. Note the numerous mounds in the photograph of MEKKαOE cells. These are aggregates that arrested at this stage.

MEKKα regulates morphogenesis and developmental timing

To examine the potential function of MEKKα, we created a mekkα null (mekkα−) strain (see Materials and Methods). mekkα− cells aggregated with normal timing (data not shown) but developed more rapidly than wild-type cells during the multicellular stages, producing fruiting bodies at 18 hr compared to 24–26 hr for wild-type strains (Fig. 2B). The fruiting bodies had smaller sori (spore heads) and longer stalks than in wild-type strains, indicating fewer spores. A putative dominant-negative MEKKα was created by mutating the 199 lysine residue in the putative ATP-binding site of the kinase domain to alanine (MEKKαK199A) to create a MEKKα that is expected to lack kinase activity. Cells constitutively expressing MEKKαK199A from the Act15 promoter exhibited two developmental abnormalities similar to mekkα null cells. MEKKαK199A-expressing cells showed precocious development, forming fruiting bodies ∼5 hr earlier than wild-type strains. There was a significant reduction in the number of spores (15% of wild type), suggesting that MEKKα was required for efficient prespore/spore-cell differentiation. By 36 hr, the spore mass (sorus) was glassy and contained predominantly water (Fig. 2B). The stronger morphological phenotype of the MEKKαK199A-expressing cells compared to mekkα− cells suggests a redundancy in the MEKKα part of the pathway that is blocked by MEKKαK199A and/or may be caused by the sequestering of components required for multiple pathways that function to mediate prespore/spore-cell differentiation.

In contrast, cells overexpressing MEKKα or MEKKαΔWD (MEKKα in which the WD40 repeats are deleted) from the Act15 promoter exhibited very delayed development, with up to 50% of the aggregates arresting at the mound stage (Fig. 2C). The aggregates that developed further did not form slugs until ∼24 hr, and these slugs migrated for an extended period of time before culminating (∼36 hr; Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the MEKKα overexpressors were impaired in proceeding past the mound stage and defective in the initiation of culmination. Moreover, MEKKαΔWDOE cells that developed further showed very abnormal morphogenesis (Fig. 2C). These overexpression defects appear to result from defects in prespore cells because expression of either MEKKα or MEKKαΔWD from the SP60 prespore-specific promoter, but not from the ecmAO prestalk-specific promoter, results in delayed development and abnormal morphogenesis (data not shown).

We examined the effect of overexpressing the F-box motif and WD40 repeats at high levels from the Act15 promoter, which might disrupt the function of the F-box/WD40 repeats of the endogenous MEKKα. These overexpressor strains exhibited very delayed development, with <40% of cells proceeding through development (data not shown). The sori of the fruiting bodies were severely deformed (Fig. 2B) and contained only 10% of the heat- and detergent-resistant spores found in wild-type strains (data not shown). These results suggest that MEKKα plays an important role in regulating prespore cell-type differentiation.

MEKKα regulates spatial patterning

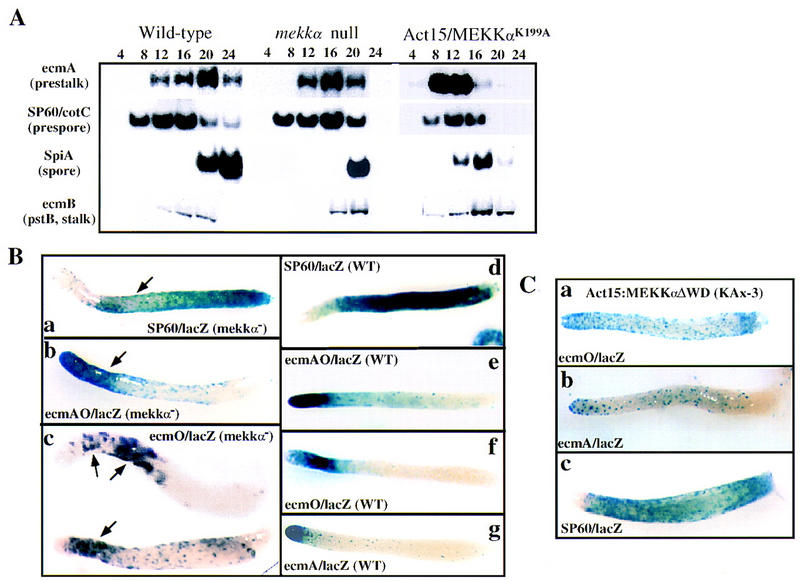

To examine a role for MEKKα in regulating cell-type differentiation, cell-type-specific markers in MEKKα mutant strains were analyzed by developmental RNA blot analysis (Fig. 3). Consistent with their precocious development during the multicellular stages, mekkα− cells exhibited a precocious peak of expression of the prestalk-specific genes ecmA and ecmB and the spore-specific marker SpiA. Compared to wild-type cells, the level of ecmA expression in mekkα− cells showed a slight, but reproducible increase, whereas the level of expression of the spore marker SpiA was reduced (Fig. 3A). This is consistent with a longer stalk and smaller sorus in mekkα− fruiting bodies. These effects were even more pronounced in cells expressing MEKKαK199A, consistent with this strain’s more severe developmental phenotype. In these cells, ecmA and ecmB exhibited an elevated and precocious expression. Expression of the prespore- and spore-specific markers SP60/cotC and SpiA was reduced and the time of expression was earlier than in wild-type cells, consistent with the more rapid development of this strain. Overexpression of either MEKKα or MEKKαΔWD resulted in an extended period of expression of both the prestalk gene ecmA and the prespore gene SP60/cotC, as would be expected from the extended period of slug migration in these strains (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Analysis of gene expression and patterning in MEKKα mutants. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from wild-type, mekkα−, and MEKKαK199A overexpressing cells at different stages of development as indicated. Blots were hybridized with probes for ecmA (prestalk-specific), SP60 (prespore-specific), SpiA (spore-specific), and ecmB (pstB- and ALC-specific). (B) Spatial patterning of prestalk and prespore cells in wild-type and mekkα− strains. Cells were transformed with the cell-type-specific lacZ reporter. For all lacZ expression studies, clonal isolates were used and several independent isolates were examined. Representative organisms are shown. Each panel is labeled to indicate the marker used and the genetic background. The arrowhead in a (SP60/lacZ, mekkα− cells) points to the lighter staining area in the region of potential pstO/prespore domain overlap. The arrowhead in b (ecmAO/lacZ, mekkα− cells) points to the extended prestalk-staining region in mekkα− cell slugs. The arrowheads in c (ecmO/lacZ, mekkα− cells) points to the larger pstO domain that shows a more scattered pattern (not all cells stain) and a region of potential pstO/prespore domain overlap. (C) Spatial patterning of prestalk and prespore cells in strains overexpressing MEKKαΔWD. Cells expressing MEKKαΔWD show very scattered staining throughout most of the slug of the pstA- and pstO/ALC-specific reporters ecmA/lacZ and ecmO/lacZ, respectively.

Because the developmental Northern blots of MEKKα mutants suggested an abnormality in cell-type differentiation that usually causes aberrant spatial patterning, we examined the spatial patterning of prestalk and prespore cells in the mekkα−- and MEKKα-overexpressing strains by using cell-type-specific lacZ reporters and histochemical staining for β-gal activity. In mekkα− slugs, there was a decrease in the size of the prespore zone (staining region; Fig. 3Ba,d) as shown by the expression pattern of the prespore reporters SP60/GFP and SP60/lacZ (Haberstroh and Firtel 1990; data for SP60/GFP not shown). There was a concomitant increase in the size of the prestalk zone stained by ecmAO/lacZ reporter (Fig. 3Bb, compare to wild-type Fig. 3Bd,e). [ecmAO is the promoter of the ecmA gene and is expressed at a high level in pstA cells and a lower level in pstO cells (Early et al. 1993).] This increase in the prestalk region appears to be specific for the pstO cells, as observed by the size of the region expressing ecmO/lacZ, a reporter expressed in pstO cells and anterior-like cells (ALCs) (Early et al. 1993; Fig. 3B, cf. c and f). The size of the more anterior pstA domain, as determined by the expression pattern of the pstA-specific reporter ecmA/lacZ, was the same as in wild-type cells (data not shown). These data indicate that prespore cell-type differentiation is compromised in mekkα− slugs and there is an increase in the size of the pstO domain.

In addition to an increase in the size of the region occupied by pstO cells, we observe that the pstO (ecmO/lacZ-expressing) cells are more scattered within the slug and do not form a tight domain as they do in wild-type slugs (Fig. 3Bc). Comparison of the staining patterning in many slugs indicates that the pstO and prespore domains overlap partially (Fig. 3Ba,b), suggesting an intermixing of the pstO and prespore cells in this region. Thus, mekkα− slugs appear to lack the normally well-defined boundary between the prespore and prestalk domains. To determine if this potential overlap of the prestalk and prespore domains might be accounted for by cells that express both prestalk and prespore markers, double immunofluorescence staining was performed in mekkα− cells expressing the ecmO/lacZ reporter using the MUD1 prespore cell-specific mAb (Krefft et al. 1985) and an antibody against β-gal to identify pstO cells. No cells that expressed both markers were observed (data not shown).

A role for MEKKα in regulating cell-type patterning is even more evident from the staining pattern of the cell-type reporters in cells expressing MEKKαΔWD. In these strains, prespore cells were present almost uniformly throughout most of the slug and found almost to the very anterior (Fig. 3Cc). However, the staining appeared very diffuse, suggesting that not all of the cells in this expanded region express the marker. Consistent with this observation, staining of the pstO- and pstA-specific reporters ecmO/lacZ and ecmA/lacZ, respectively, was also diffuse and scattered throughout most of the slug, with an apparent loss of the normally distinct pstA, pstO, and prespore compartments (Fig. 3Ca,b, compare to wild-type pattern, Fig. 3Bf,g). These data suggest that MEKKα levels, and presumably kinase activity, are important in regulating the position of pstO and prespore cells within the slug.

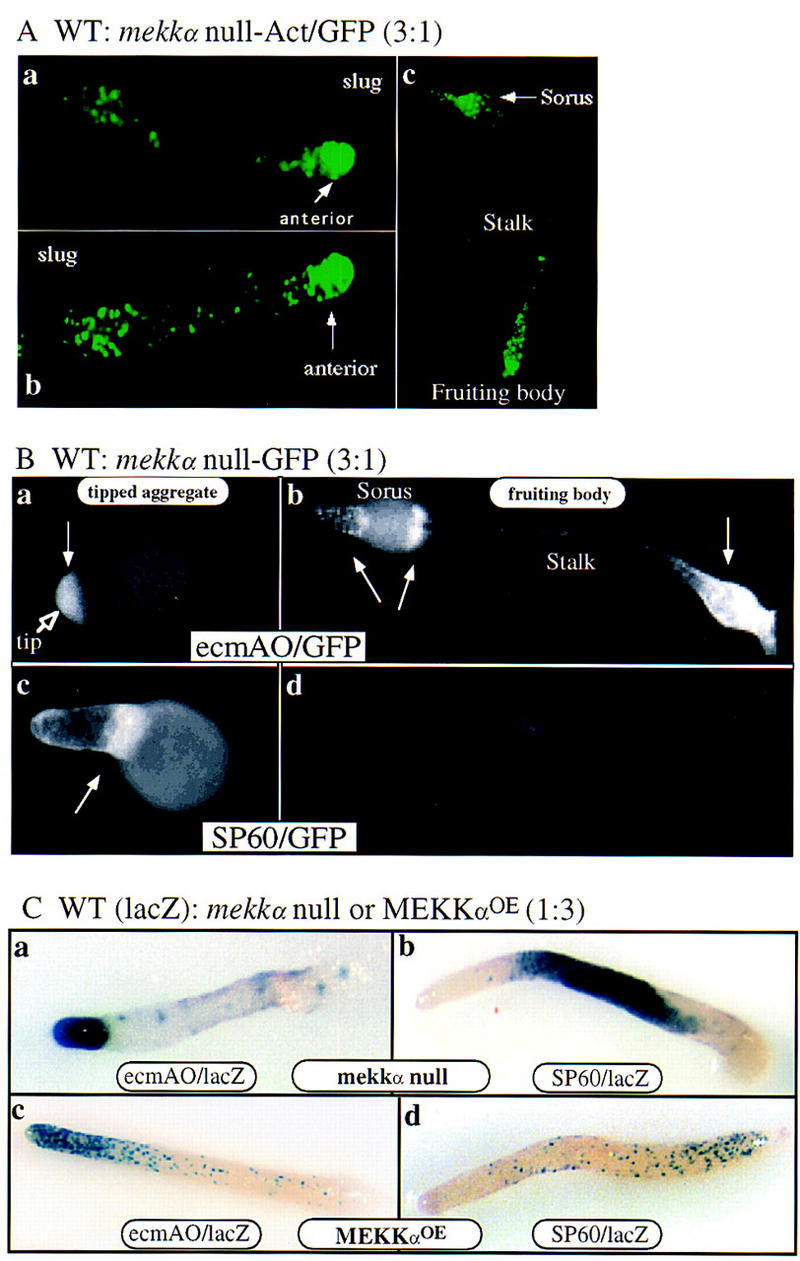

Spatial patterning of prestalk and prespore cells in chimeras: mekkα− cells differentiate into prestalk cells preferentially

A decrease in the number of prespore cells and an increase in pstO cells in mekkα− cells suggest that, in the absence of MEKKα function, cells might have a tendency to differentiate into prestalk cells. To better understand the properties of the mekkα− cells, we observed the developmental potential and the position of wild-type and MEKKα mutant strains tagged with GFP or lacZ reporter in chimeric organisms. This allows us to differentiate between potentially cell-autonomous and nonautonomous functions. When mekkα− cells expressing Act15/GFP (which is uniformly expressed in all cells) were mixed with wild-type cells in a ratio of 1:3 and plated for development (Fig. 4Aa,b), most of the mekkα− cells in slugs were localized to the anterior prestalk domain and the most posterior rearguard compartment. The rearguard compartment is composed of two prestalk cell types: ALCs and pstAB-derived cells (Sternfeld 1992). In the fruiting body, mekkα− cells differentiate mainly into the lower portion of stalk and the basal disk (derived from rearguard cells) and upper cup of fruiting body (derived from pstO/ALCs). Few mekkα− cells were found in the prespore domain and mekkα− cells did not differentiate into spores, as no GFP-expressing spore cells were observed (Fig. 4Ac; data not shown). The fruiting bodies exhibited an enlarged lower stalk and basal disc, suggesting that the chimeras contain an elevated number of pstO and ALCs, probably differentiated from the mekkα− cells. mekkα− prestalk cells (as defined by those expressing ecmAO/GFP) were localized in the tip of chimeric mound and the basal disk, lower portion of the stalk, and upper and lower cups of the sorus (Fig. 4Ba,b; the light staining on the sorus in Fig. 4Bb is caused by the ALC-derived ‘epithelial’ layer often found covering the sorus). These results suggested that in chimeras with wild-type cells, mekkα− cells differentiated into prestalk cells preferentially.

To examine whether mekkα− cells have a cell-autonomous defect that prevents them from differentiating into prespore cells in these chimeras, mekkα− cells were tagged with the prespore-specific reporter SP60/GFP. In the tipped aggregate, when cell sorting first establishes the spatial pattern of the cell types, SP60–GFP-tagged mekkα− cells were found primarily in a band below the prestalk domain in the very anterior of the prespore region (Fig. 4Bb). However, expression of this marker was lost subsequently and, by mid-culmination (Fig. 4Bd) or later stages (data not shown), no GFP was detected. The simplest explanation is that mekkα− prespore cells form in these chimeras initially and then the expression of this marker is lost in mekkα− cells, probably because differentiation of the putative mekkα− prespore cells is not stable. This is consistent with the mekkα− cells in chimeras contributing only to the prestalk and stalk compartments in slugs and fruiting bodies. Reciprocal mixing experiments in which one part tagged wild-type cells was mixed with three parts unlabeled mekkα− cells support the above model. Wild-type cells were able to form the very anterior of the prestalk domain as shown by the fact that ecmAO/lacZ-tagged wild-type cells localized to the very anterior pstA domain, as do mekkα− cells (Fig. 4Ca). The wild-type prespore cells localize to a central band of cells in the slug (Fig. 4Cb). A large posterior domain, seen as an unstained region in the SP60/lacZ panel, must be composed of mekkα− cells and presumably represents an enlarged rearguard domain (see above), which is probably composed of mostly mekkα−-derived pstO/ALCs. In toto, these data are consistent with the decreased ability of mekkα− cells to participate in the formation of the prespore domain in the slug in the presence of wild-type cells. As mekkα− cells form a true prespore domain when developed by themselves, we suggest that this regulation is nonautonomous and dependent on morphogenetic factors such as cAMP and the prestalk differentiation factor DIF in the slug and the ability of mekkα− and wild-type cells to sense and respond to these factors.

Because mekkα− cells have a propensity to become prestalk cells, it is reasonable to believe that cells having higher activity of MEKKα differentiate into prespore cells. Thus, similar chimeric analyses were conducted with Act15/MEKKαOE wild-type cells mixed with wild-type cells carrying lacZ reporters in a ratio of 3:1 (Fig. 4Cc,d). In contrast to the above chimeric analysis, wild-type cells localized preferentially to the prestalk rather than the prespore region of migrating slugs (Fig. 4Cc,d). Wild-type cells expressing the prestalk reporter ecmAO/lacZ showed staining that extended over the pstA and pstO domains, indicating that the wild-type cells differentiated into pstA and pstO cells in the chimeras. However, very few wild-type prespore cells formed, as indicated by the few wild-type cells within the slug that express the prespore reporter SP60/lacZ. These were found concentrated towards the posterior of the prespore domain. Thus, in mekkα/wild-type chimeras, mekkα− cells become prestalk cells preferentially and do not contribute to the prespore domain, whereas in MEKKαOE/wild-type chimeras, very few of the wild-type cells contribute to the prespore domain. These data suggest that the level of expression of MEKKα determines the propensity to contribute to the formation of the prestalk or prespore domains in a chimera.

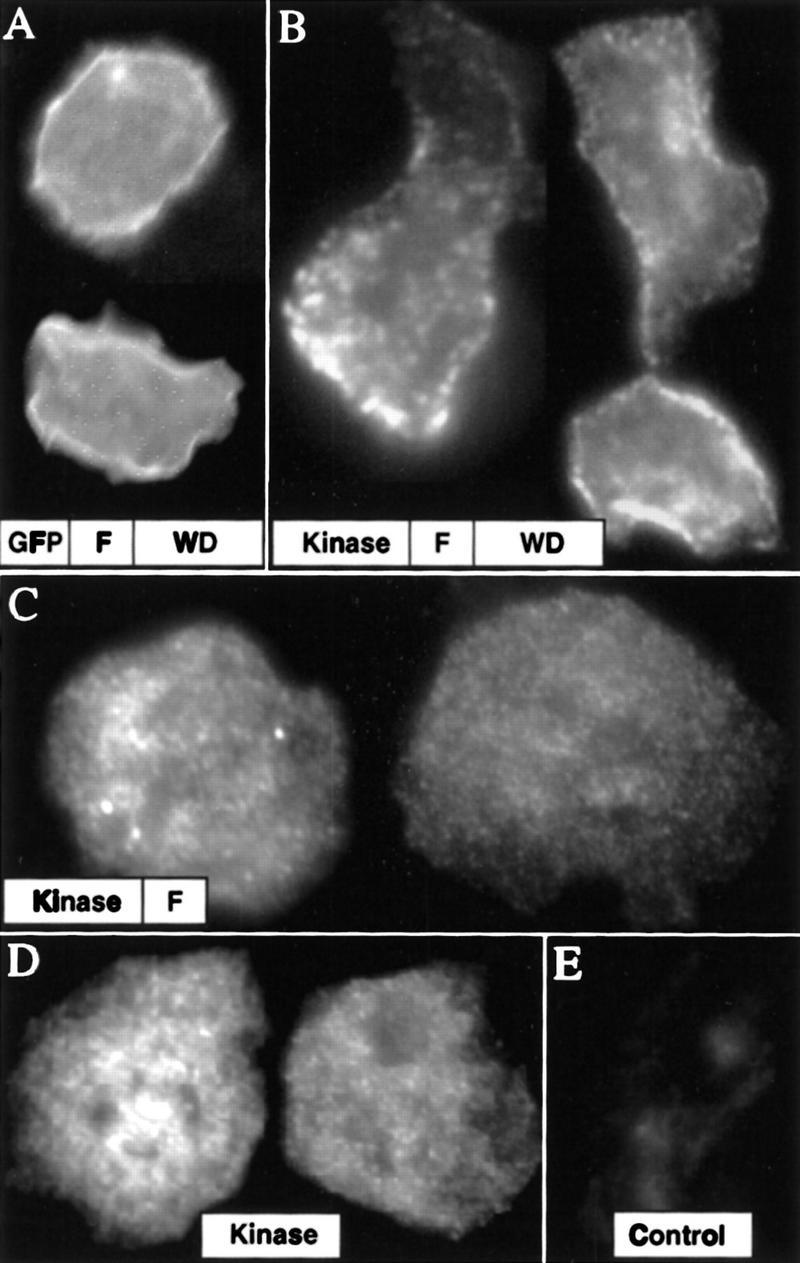

Subcellular localization of MEKKα

The fact that we obtained dominant phenotypes by overexpressing the F-box and WD40 repeats suggests that the F-box/WD40 domain of MEKKα might interact with proteins that play important roles in regulating the activity and subcellular localization of MEKKα. We examined the subcellular localization of the F-box/WD40 and MEKKα by using GFP–F-box/WD40 fusion protein or FLAG-tagged MEKKα. The F-box/WD40–GFP fusion protein exhibited a predominantly cortical staining (Fig. 5A), suggesting that these domains might localize MEKKα to the membrane. Controls with GFP alone showed a uniform staining pattern throughout the cell (data not shown). Consistent with the distribution of GFP–F-box/WD40, MEKKα was localized predominantly at the periphery of the cells, possibly in the cortex or the plasma membrane as examined by indirect immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5B). However, FLAG–MEKKα staining was not distributed uniformly but showed a clustered, granular pattern. FLAG-tagged MEKKα lacking WD40 repeats (Fig. 5C) or both the F-box and WD40 repeats (containing only the kinase domain; Fig. 5D) were no longer targeted to the membrane, but found in clusters throughout the cytoplasm, supporting the model that the WD40 repeats are an important component in targeting MEKKα to the cell cortex or plasma membrane.

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of MEKKα. (A) Localization of GFP-tagged F-box/WD40 protein in the cortical region of the cytoplasmic membrane. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of cells expressing Flag-tagged MEKKα. The staining is clustered and mainly localized in the membrane cortex. (C) Staining of a truncated Flag-MEKKα from which WD40 repeats were deleted (MEKKαΔWD40). (D) Staining of FLAG-MEKKα missing both F-box and WD40 repeats (MEKKαΔF-box/WD40). (E) Control, untransformed cells.

The F-box/WD40 repeat domain interacts with components of the ubiquitination/ deubiquitination pathway and regulates MEKKα stability

We performed two-hybrid screens to identify Dictyostelium proteins that might interact with the MEKKα F-box and WD40 repeats (Lee et al. 1997). One of the genes recovered in the screen is UbcB, encoding an E2 class ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that links ubiquitin covalently (often in association with E3 ligase) to proteins to be degraded by 26S proteasomes (Varshavsky 1997). We isolated this gene previously in a REMI screen and ubcB null (ubcB−) cells show a delay at the mound stage and eventually arrest at the first finger stage (Clark et al. 1997). Analysis of these cells showed that the developmental pattern of several ubiquitin-linked proteins was altered. Another identified gene encodes a putative UBP (designated UBPB), a potential ubiquitin hydrolase that removes ubiquitin from proteins. These enzymes are thought to play roles in stabilizing proteins by preventing them from being targeted for degradation and/or in ubiquitin precursor processing (Hochstrasser 1995, 1996). The sequence of the UbpB open reading frame (ORF) revealed the conserved Cys and His sequence motifs, which may form an active site and are conserved in all known UBPs (not shown).

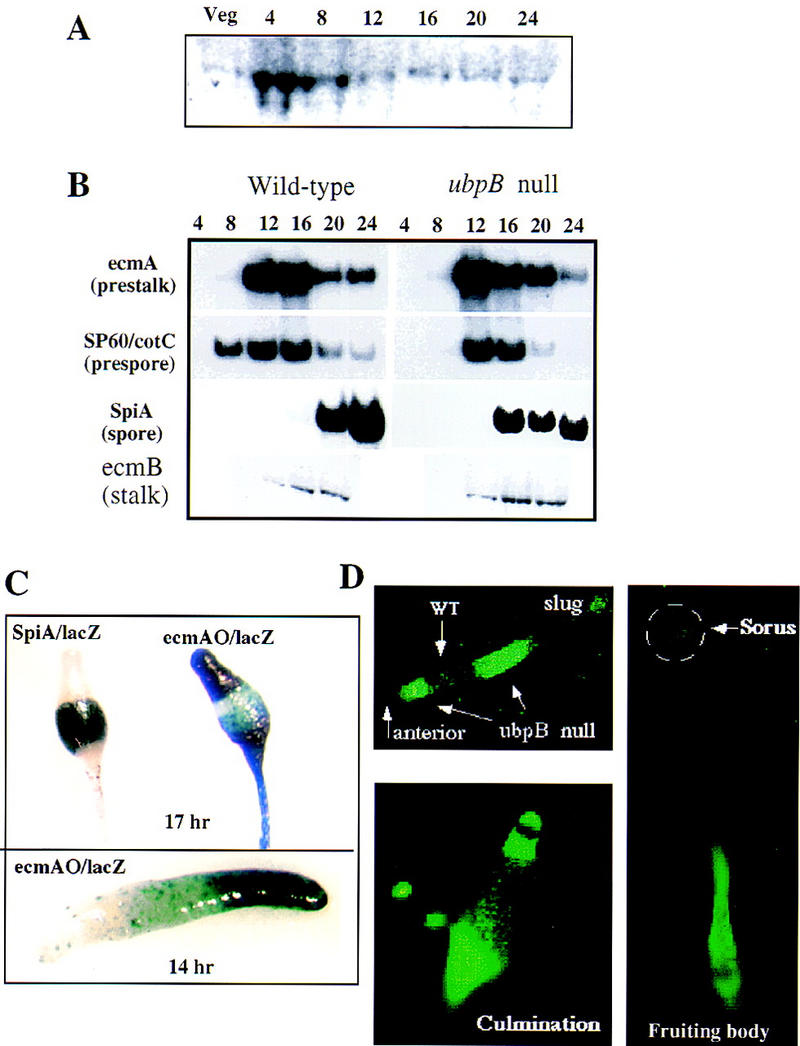

UbpB expresses a single developmentally regulated transcript (2.0 kb) that is found at low levels in vegetative cells and at higher levels during aggregation and mound formation (4 and 8 hr; Fig. 6A). UbpB was disrupted by homologous recombination and disruptants were identified by Southern blot analysis as described for mekkα− cells (see Materials and Methods). As observed with mekkα− cells, ubpB null (ubpB−) cells exhibit precocious development, similar to that of mekkα− strains. They form fruiting bodies at ∼17 hr (Fig. 6C; data not shown) and exhibit precocious expression of the spore marker SpiA (Fig. 6B). The expression levels of the prespore/spore markers are lower in the ubpB− cells compared to wild-type cells, whereas expression of the prestalk/stalk marker ecmB is elevated slightly.

Figure 6.

Analysis of UBPB expression during growth and development and the phenotype of the ubpB− mutant. (A) Developmental RNA blot of UBPB expression. Time in development is shown. (Veg) Vegetative cells. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from wild-type and ubpB− cells at different stages of development. Blots were hybridized with probes for ecmA, SP60, ecmB, and SpiA. (C) Spatial patterning of prestalk and prespore cells in ubpB− strains. Cells were transformed with the prespore-specific reporter SP60/lacZ, ecmAO/lacZ, or SpiA/lacZ and clones were isolated. In ubpB− cells, the prespore region containing cells expressing SP60/lacZ is reduced compared to the wild-type prespore region. The pstA/O domain is expanded in null cells. (D) Prestalk localization of ubpB− cells expressing Act15/GFP in the chimera of wild-type cells and ubpB− cells in a ratio of 3:1.

We performed an analysis of cell-type patterning in ubpB− cells similar to that described above for mekkα− cells using cell-type-specific reporters. Our analyses of ubpB− cells show an enlarged prestalk domain (ecmAO/lacZ) and a reduced prespore (sp60/lacZ) domain in the slug and spore domain in a fruiting body (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the strain does not form the normal spherical sori seen in mature wild-type fruiting bodies. Instead, the sori remain elongated, similar to those seen in wild-type fruiting bodies that are not fully mature (Fig. 6C). The upper and lower cups of the fruiting body, which are derived from prestalk cells and ALCs, are enlarged. The spore-containing region, as determined from SpiA/lacZ expression, is reduced. These abnormalities suggest that UBPB activity is required for proper prespore cell patterning and ubpB− cells differentiate into prestalk cells preferentially.

To determine if ubpB− cells also have a propensity to become prestalk cells, we examined the fate of ubpB− cells in similar mixing experiments. ubpB− cells were tagged with Act15/GFP and mixed with wild-type cells in a ratio of 1:3. As with mekkα− cells, most of the tagged ubpB− cells localized to prestalk-derived compartments in the anterior and posterior of the slug and differentiated into the lower stalk and basal disk in mature fruiting bodies (Fig. 6D). This suggests that ubpB− cells, like mekkα− cells, have a propensity to develop into prestalk cells.

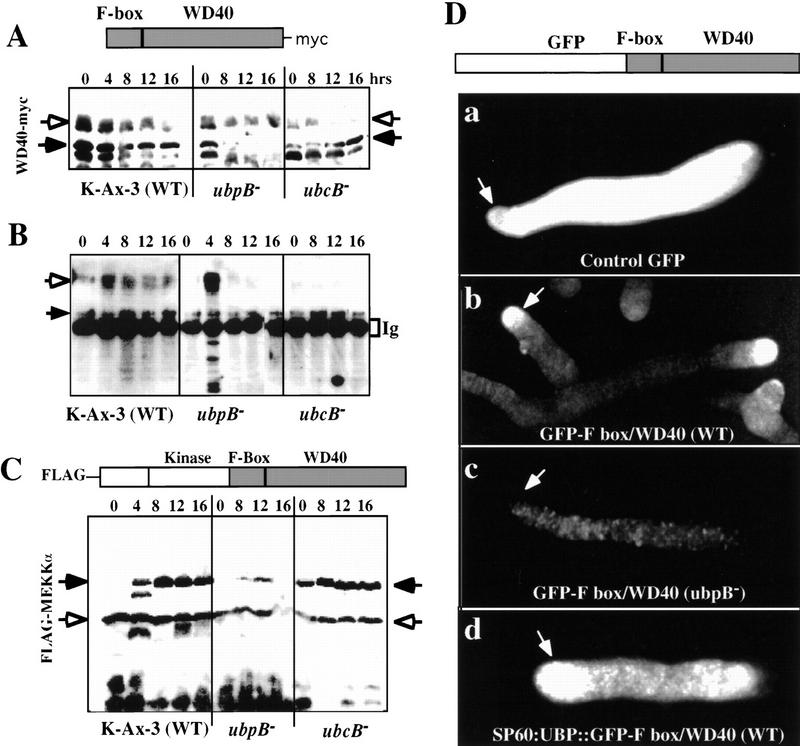

Differential stability of MEKKα in various genetic backgrounds: evidence for regulation of MEKKα stability by UBCB and UBPB

Identification of UBC and UBP as MEKKα-interacting proteins suggests that MEKKα may be regulated by ubiquitin-dependent degradation. This possibility is consistent with the fact that MEKKα has an F-box sequence that is thought to be involved in ubiquitin-dependent degradation of cyclin F and other proteins (Bai et al. 1996; Skowyra et al. 1997). To examine whether MEKKα has a differential stability in ubcB− and ubpB− cells and whether that stability is mediated via the F-box/WD40 repeats, a myc-tagged F-box/WD40 domain was expressed from the Act15 promoter in wild-type, ubcB−, and ubpB− cells (Fig. 7A). In wild-type cells, the level of the tagged protein (as marked by the closed arrowhead) was high during early development, but decreased in amount during later development after mound formation. No bands were observed in control, untransformed cells, indicating that the observed bands were specific for those carrying the myc epitope. In addition, a higher molecular weight band (open arrowhead), which probably is polyubiquitinated, was observed that also decreased after mound formation. Bands of this same mobility react with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (see below, Fig. 7B). Lower molecular weight myc-tag-containing bands, which may represent degradation products as they carry the myc tag, were observed. In ubcB− cells, a band the size of the tagged F-box/WD40 repeats accumulated in intensity during development and a reduced amount of the higher molecular weight band was seen. The latter observation would be predicted if UBCB participated in the ubiquitination of MEKKα via the F-box/WD40 repeats, which then targeted the protein for degradation. In ubpB− cells, the tagged F-box/WD40 band and a diffuse higher molecular weight set of bands were observed in vegetative cells. As development proceeded, the intensity of the band of the F-box/WD40 repeats decreased significantly faster than the band of wild-type cells.

Figure 7.

Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of MEKKα. (A) Western blot analysis of the stability of myc-tagged F-box/WD40 protein in wild-type, ubpB−, and ubcB− cells. Extracted proteins (20 μg) were resolved in a 10% polyacrylamide gel, blotted onto PVDF membrane, and stained with anti-myc antibody. Closed arrowheads indicate the position of the expected 60-kD F-box/WD40 protein and open arrowheads indicate the higher molecular weight proteins, which might be polyubiquitinated. (B) Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated F-box/WD40 protein with anti-ubiquitin antibody. myc-F-box/WD40 protein in wild-type, ubpB−, and ubcB− cells was immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody and probed with anti-ubiquitin antibody. Solid arrowheads indicate the F-box/WD40 protein and open arrowheads indicate polyubiquitinated proteins. (C) Western blot analysis of the stability of Flag-tagged MEKKα in different genetic backgrounds. Solid arrowheads indicate the expected 100-kD MEKKα and open arrowheads indicate smaller protein bands that might be proteolitic degradation productions. (D) Differential stability of the GFP–F-box/WD40 fusion in living wild-type and ubpB− slugs. GFP (a) or GFP-tagged F-box/WD40 fusion protein was ex pressed in wild-type (b) and ubpB− (c) cells.The higher GFP fluorescence in the pstA domain suggests that the turnover of the GFP–F-box/WD40 might be regulated spatially. (d) Wild-type cells expressing constitutively GFP–tagged F-box/WD40 from the Act15 promoter and UBPB from the SP60 promoter, which directs expression in prespore cells. The samples shown in A and B are from different experiments. Control blots of untransformed wild-type cells show no immunoprecipitated bands using the anti-myc antibody.

We examined the ubiquitination of F-box/WD40 repeats during development by performing immunoprecipitation of the myc-tagged F-box/WD40 protein with anti-myc antibody followed by probing a Western blot with anti-ubiquitin antibody (Fig. 7B). In wild-type cells, we observed higher molecular weight polyubiquitinated bands (open arrowhead), with the level of ubiquitination peaking at 4–8 hr of development. Starting at the mound stage (8 hr of development), smaller bands were observed. We observed these smaller bands also in the Western blot of FLAG-tagged holo-MEKKα, so these bands are likely to represent the degradation products of F-box/WD40. They are not observed in control, untransformed cells (data not shown). Similar to our observations in wild-type cells, a strong, polyubiquitinated F-box/WD40 band was detected at 8 hr of development in ubpB− cells, as were many lower molecular weight bands. This finding suggests the F-box/WD40 protein is ubiquitinated and degraded extensively at this time in development. In ubcB− cells, we observed a significantly reduced level of ubiquitinated F-box/WD40 and the smaller molecular weight degradation products. However, there was still a signal at the position of the F-box/WD40 repeat in the gel, suggesting that some ubiquitination occurred and there is some redundancy in the ubiquitination pathway. These results are consistent with the F-box/WD40 repeat protein being polyubiquitinated and requiring UBCB for efficient ubiquitination and the targeting of the protein for degradation. Our results are also consistent with UBPB stabilizing the F-box/WD40 repeat protein by deubiquitinating the protein.

We also examined the stability of a Flag-tagged holo-MEKKα in the three genetic backgrounds. As shown in Figure 7C, no detectable full-length MEKKα is found in vegetative wild-type cells, although we observe an ∼55-kD protein, which may be either a cleavage or degradation product (see below). In addition, we observe a large amount of material migrating as very low molecular weight bands, which we expect are degradation products. Full-length MEKKα protein was observed by 4 hr of development, the time when UBPB expression increases. The amount of this band stays constant during development. In ubcB− cells, the tagged MEKKα is stable and the presence of the ∼55-kD band is observed. An important observation is that very few of the smaller bands, presumably MEKKα degradation products, are observed, suggesting that MEKKα degradation is reduced in this strain. In contrast, the tagged MEKKα is very unstable in ubpB− cells and only a small amount of the full-length protein or the ∼55-kD band is observed at any stage of development. Instead, we observed numerous lower molecular weight bands that presumably represent degradation products. By comparing the amount of the full-length MEKKα to the amount of low molecular weight, putative degradation products, we conclude that MEKKα is least stable in ubpB− cells and most stable in ubcB− cells. Interestingly, the 110-kD band representing FLAG-tagged MEKKα was absent in vegetative wild-type and ubpB− cells. However, we observe a FLAG-tagged protein of ∼55 kD, the expected size of MEKKα lacking the F-box and WD40 repeats. As this protein is tagged at the amino terminus, the deleted protein must be lacking carboxy-terminal residues including the WD40 repeats. It is not clear if this is a normal cleavage product or a result of the overexpression of MEKKα.

We also tested the ubiquitination of MEKKα in the three genetic backgrounds and found a pattern similar to that observed with the F-box/WD40 domain. MEKKα exhibited a lower level of ubiquitination in ubcB− cells than in wild-type cells, with the level higher in ubpB− cells (data not shown). The above data imply that MEKKα exhibits differential stability in the three genetic backgrounds, suggesting that MEKKα is degraded in a developmentally regulated fashion and UBCB and UBPB play a role in controlling MEKKα stability.

The speculation that the degradation of MEKKα might be cell-type specific arose from the observation of phenotypes from expressing MEKKα in prespore cells, but not in prestalk cells. To determine if we could observe a differential stability of the F-box/WD40 repeats in living wild-type and ubpB− slugs, we expressed GFP or GFP–F-box/WD40 from the Act15 promoter. Clones that expressed similar levels of the transcript in vegetative cells were developed to the slug stage and examined for GFP fluorescence (Fig. 7D). [Note: ubcB− cells produce very few slugs, which are abnormal and not observed until 20 hr of development (Clark et al. 1997).] In wild-type slugs expressing GFP–F-box/WD40, we observed a very high level of fluorescence in the anterior pstA domain but a much lower level of expression in the pstO and prespore domains (Fig. 7Db). This is in sharp contrast to control cells expressing free GFP, which showed very strong fluorescence that was distributed throughout the slug uniformly (Fig. 7Da, also examined using shorter exposures; data not shown). Thus, the lower fluorescence of GFP–F-box/WD40 in the prespore domain suggests that GFP–F-box/WD40 turnover is spatially regulated, being higher in prespore than prestalk cells. ubpB− cells expressing GFP–F-box/WD40 showed an even lower level of fluorescence throughout the slug, suggesting that the GFP–F-box/WD40 fusion protein turned over rapidly in all cell types in this genetic background. These results are consistent with the F-box/WD40 repeats mediating turnover of the associated protein and UBPB differentially regulating stability of this protein in vivo. To test this further, we overexpressed UBPB only in prespore cells using the SP60 promoter in wild-type cells expressing GFP–F-box/WD40. As shown in Figure 7Dd, we observed high fluorescence in the prespore domain, especially in the posterior of this domain. This result indicates that overexpression of UBPB in prespore cells can help stabilize the GFP–F-box/WD40 protein in wild-type cells.

Discussion

MEKKα is required for pstO/prespore cell patterning and maintaining the prespore state of differentiation

We have identified a gene, MEKKα, which probably encodes a MEK kinase because of its very high homology in the kinase domain to known MEKKs, the first kinase in MAP kinase cascades. Our findings indicate that MEKKα plays a key role in a new regulatory pathway by which cell-type differentiation, morphogenesis, spatial patterning, and developmental timing are controlled. Whereas components of three MAP kinase pathways required for chemotaxis, activation of adenylyl cyclase, and prespore cell differentiation have been identified previously in Dictyostelium (Gaskins et al. 1994, 1996; Segall et al. 1995; Ma et al. 1997), we expect that they are independent pathways and unrelated to the pathway containing MEKKα. MEKKα contains an F-box, a domain known to control ubiquitin-mediated degradation of proteins, and WD40 repeats, which we show are important for targeting MEKKα to the cell cortex or possibly the plasma membrane. We demonstrate that MEKKα’s stability, and thus its function, is differentially regulated temporally and in a cell-type-specific fashion via developmentally regulated ubiquitination/deubiquitination. Our results represent a novel mechanism by which MAP kinase cascade components can be controlled.

Our data suggest that MEKKα plays several roles in regulating cell-type patterning and morphogenesis. We have shown that disruption of MEKKα or overexpression of a putative dominant negative construct (MEKKαK199A) results in a loss of proper spatial patterning, including an expansion of the pstO domain, a concomitant reduction of the prespore domain, a smaller sorus, and a longer stalk. This indicates that MEKKα may be required to maintain the proportions of prespore cells in the multicellular organism. MEKKα also controls the boundaries between these two distinct cell-type compartments within the organism. In the null and overexpression strains, the tight cell-compartment boundaries are lost and there is an intermixing of the cell types. The effect is very extreme in strains overexpressing MEKKαΔWD in which pstA, pstO, and prespore cells are mixed throughout the slug. The phenotype could result from cells losing their spatial identity within the slug because of an abrogation of the patterning signals, thought to be cAMP and DIF, which control a cell’s position within the organism and its fate (Kay 1992; Loomis 1993; Ginsburg et al. 1995; Siegert and Weijer 1995; Williams 1995; Firtel 1996; Bretschneider et al. 1997). Alternatively, cells may lose the ability to sense and/or respond to these signals, which causes the alteration in their ability to sort in the multicellular aggregate, leading to a loss of compartment boundaries and, in the most extreme examples, an intermixing of the cell types.

The other phenotype is that mekkα− cells develop more rapidly than wild-type cells, with the major change in timing occurring after the mound is formed, the time when MEKKα expression increases during development. More rapid development is an earmark of strains having constitutively active PKA, which is known to be essential for prespore differentiation, culmination, and spore formation (Abe and Yanagisawa 1983; Simon et al. 1992; Firtel 1995; Reymond et al. 1995; Mann et al. 1997). MEKKα may integrate into this pathway. In all cells, overexpression of MEKKα or MEKKαΔWD40 results in very delayed development in which many of the aggregates arrest at the mound stage. The effect appears to result from expression in prespore cells, as overexpression of MEKKα from the SP60 prespore promoter but not the ecmAO prestalk promoter produces a similar delay and additional aberrant morphological phenotypes. The results suggest that MEKKα function is required at the time of cell-type differentiation and patterning for establishment and maintenance of proper proportioning and patterning. Its degradation, possibly preferentially in prespore cells, appears to be required for proper onset of later development and morphogenesis.

We also observed that mekkα− and ubpB− cells differentiate preferentially into structures that derive from the prestalk cell populations in a chimeric organism. This is consistent with the increase in the size of the pstO compartment in mekkα− and ubpB− slugs. Moreover, it further supports the suggestion that mekkα− cells have a reduced ability to form and/or maintain prespore cell fate, leading to an impairment in proper prestalk:prespore proportioning, possibly because of a reduced ability to recognize the morphogenetic cues within the organism. In Dictyostelium, development is highly regulative and a cell’s fate is not finally determined until culmination. Before that, prestalk and prespore cells can interconvert via a pathway that has been termed transdifferentiation, which is thought to play a role in the maintenance of spatial patterning in the slug (Abe et al. 1994). The uncommitted fate of cells in Dictyostelium slugs indicates that the cells are able to respond to environmental cues continually to regulate their state of differentiation and thus control the patterning of the organism. Our data suggest that MEKKα is one of the critical components controlling the equilibrium between the cell types, probably by maintaining prespore differentiation. We show that although mekkα− prespore cells are formed in chimeras with wild-type cells, as determined by SP60/GFP expression, GFP expression is lost in the chimeras (Fig. 4B). The simplest explanation is that SP60-expressing mekkα− cells must dedifferentiate and then differentiate into prestalk cells and eventually stalk cells later in development. This conclusion is consistent with our observation that mekkα− cells appear to participate exclusively in prestalk-derived structures in the chimeric fruiting body. It is thus possible that not only is prespore cell differentiation of mekkα− cells unstable in chimeras with wild-type cells, but prespore differentiation is compromised generally in this genetic background. Conversely, we show that in chimeras of wild-type and MEKKαOE cells, the wild-type cells preferentially become prestalk cells and the MEKKαOE cells become prespore cells. This further supports the conclusion that the level of MEKKα expression helps determine whether a cell differentiates into a prestalk or prespore cell. As this is occurring in chimeras, it must do this in the context of the signals within the slug. It is unclear whether the complete loss of the compartment boundaries in MEKKαOE cells and the intermixing of the cell types is the result of continuous transdifferentiation of pstO to prespore cells and vice versa in the region adjoining the pstO and prespore compartments.

Figure 4.

Spatial patterning in chimeric slugs. (A) Prestalk localization of mekkα− cells expressing Act15/GFP in the chimera of wild-type cells and mekkα− cells in a ratio of 3:1. (B) Localization of null cells expressing ecmA/GFP or SP60/GFP in chimeras of wild-type and null cells in a ratio of 3:1. Null cells expressing ecmA/GFP localize in the tip of the mound and later develop into stalk cells. Null cells expressing SP60/GFP are concentrated in the region near the tip of mounds. However, the expression of SP60/GFP is not prominent in the mature fruiting body. Arrowheads indicate cells expressing GFP. (C) Localization of wild-type cells in chimeras of null and wild-type cells (3:1) or MEKKα overexpression mutants and wild-type cells (3:1). (c and d) Chimeras containing one part wild-type cells and three parts MEKKαOE cells. Patterns of wild-type cells expressing either ecmAO/lacZ (c) or SP60/lacZ (d) are shown.

Interactions among various activation pathways and lateral inhibitions are thought to be involved in regulating prestalk and prespore differentiation (Kay 1992; Loomis 1993; Williams 1995; Firtel 1996). There are several known genes that function to control spatial patterning of prespore and prestalk cells and might function in the pathway mediated by MEKKα. Strains carrying null mutations of the cAMP receptor cAR4, which is thought to negatively regulate GSK3 and antagonize pathways controlled by cAR1 and 3 (Ginsburg and Kimmel 1997), or the RING-leucine zipper protein rZIP (Balint-Kurti et al. 1997), have a reduction in prestalk cells and increased prespore cells and, like strains exhibiting altered MEKKα function, a loss of the sharp pstO/prespore compartment boundary. Our data are consistent with MEKKα acting to antagonize pathways mediated by cAR4 and rZIP and activated by cAR1/3.

MEKKα levels are spatially regulated through protein ubiquitination/deubiquitination pathways

Protein ubiquitination followed by the 26S proteasome-dependent proteolysis is crucial to a variety of cellular processes (Ciechanover 1994; Hochstrasser 1995, 1996). The ubiquitination is composed of multiple reactions requiring a series of specific enzymes, including ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (UBC or E2). The predicted sequence of MEKKα has an F-box sequence and WD40 repeats, which are often found in proteins subjected to degradation via a ubiquitin-dependent pathway (Bai et al. 1996). Several proteins involved in cell-cycle regulation such as Cdc4 and Met30 of budding yeast, MD6 of mouse, and Cyclin F and Skp2 of human have an F-box, which is sometimes associated with WD40 repeats (Cdc4, Met30, MD6). The F-box has been suggested to be a receptor for phosphorylated ubiquitination targets, with Skp1 linking the F-box/target complex to ubiquitination machinery (Bai et al. 1996; Skowyra et al. 1997). Our data are consistent with the conclusion that the F-box/WD40 repeats in MEKKα control MEKKα turnover via ubiquitination and deubiquitination. A UBC and a UBP were identified as proteins interacting with MEKKα in a yeast two-hybrid screen. mekkα− and ubpB− cells develop rapidly, show increased prestalk and decreased prespore domains, and differentiate preferentially into prestalk cells in chimeras with wild-type cells. UBPs are thought to remove ubiquitin from proteins, making them less likely to be degraded by the 26S proteasome. The loss of UBP function, therefore, might lead to increased MEKKα ubiquitination and a more rapid turnover of MEKKα, as our data suggest. This should result in a reduced level of MEKKα activity, possibly producing a phenotype similar to that of mekkα− cells, as we observe.

Cells lacking the E2 UBCB (ubcB− cells), like MEKKαOE cells, exhibit a significant delay at the mound stage and arrest at the first finger stage (Clark et al. 1997). The developmental delay in ubcB− cells, in which MEKKα is more stable and thus might be expected to have higher MEKKα activity or be mislocalized, exhibits some properties similar to those of MEKKαOE strains. We have shown previously that multiple ubiquitinated proteins have altered developmental patterns of ubiquitination as determined on developmental Western blots using an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Clark et al. 1997). It is probable that the ubcB− phenotype results from altering the ubiquitination pattern and possibly the kinetics of degradation of several of these proteins.

The strongest evidence for a role of UBPB and UBCB in the regulation of MEKKα turnover is the differential stability of the tagged F-box/WD40 protein and MEKKα in wild-type, ubpB−, and ubcB− cells. These proteins are most stable in ubcB− cells and least stable in ubpB− cells, consistent with UBCB controlling the ubiquitination and degradation of MEKKα through the F-box/WD40 repeats and with UBPB regulating MEKKα’s stability. We show that the proteins are differentially ubiquitinated in the various genetic backgrounds. All of our data are consistent with our proposal that UBCB and UBPB regulate MEKKα stability. The data are also consistent with this regulation being developmentally controlled, as full-length MEKKα expressed from the Act15 promoter is not detected in wild-type cells until the time of development when UBPB expression is induced.

The observation that overexpression of mutant MEKKα proteins results in phenotypes when the proteins are expressed in prespore but not prestalk cells also suggests strongly spatial/cell-type regulation of MEKKα degradation. Our in vivo analysis examining the level and spatial distribution of GFP–F-Box/WD40 fluorescence in living slugs supports strongly the differential degradation of MEKKα. In wild-type slugs, the GFP–F-Box/WD40 showed a much stronger fluorescence in the anterior, pstA population than the remainder of the slug, compared to control GFP alone showing very strong fluorescence throughout the slug. In ubpB− cells, only a low level of scattered staining is observed, consistent with a higher rate of degradation of the protein in these cells. Thus, the Western blot data and the in vivo fluorescence analysis suggest strongly that the F-box and WD40 repeats target MEKKα for degradation and/or processing and this targeting may be spatially and temporally regulated in Dictyostelium. A strong indication that the stability is mediated by UBPB is derived from our results demonstrating that overexpression of UBPB in prespore cells stabilizes the GFP–F-Box/WD40 in these cells. We conclude that MEKKα is a substrate for UBCB and UBPB. Although substrates for other UBCs have been identified, we know of no reports in which a substrate for a UBP has been identified other than MEKKα.

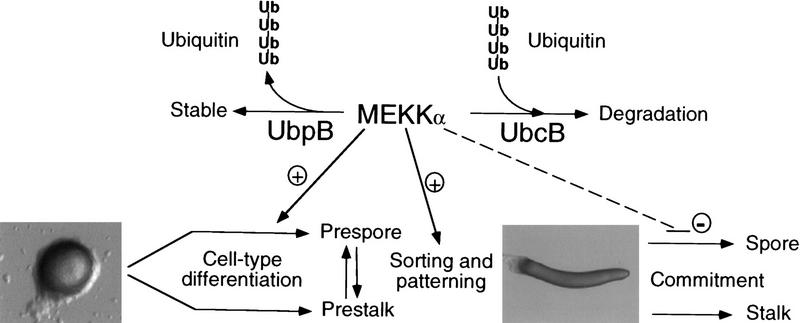

A model for the function of MEKKα is shown in Figure 8. MEKKα is required for proper prespore cell patterning and maintaining cells in the prespore state of differentiation. In this model UBPB and UBCB differentially control MEKKα degradation and/or processing and UBPB functions genetically to potentiate prespore cell differentiation. MEKKα is required for patterning and developmental timing, but its degradation may also be required for the initiation of culmination. This is reminiscent of the regulation of cyclins during mitosis. Cyclins are required to pass through a stage but must be later degraded by ubiquitin-directed proteolysis (Surana et al. 1991; Amon et al. 1994; Seufert et al. 1995; Amon 1997). The regulation of MEKKα may have direct parallels to that of cyclins during the cell cycle, whereby the temporal and spatial control of MEKKα function is mediated partially through its degradation.

Figure 8.

Model for MEKKα function. MEKKα is required for normal prespore cell-type differentiation and sorting and/or patterning of prestalk and prespore cells as reflected in the phenotypes of null cells, cells expressing MEKKαN, and cells overexpressing MEKKα in which there is a loss of the distinct boundaries between the prestalk and prespore domains. MEKKα is also required for maintaining the prespore state, as suggested by the developmental propensity of mekkα− cells to differentiate into prestalk cells in chimeras. Overexpression of MEKKα− in prespore cells keepscells from entering terminal differentiation, resulting in delayed development and abnormal patterning. We propose that UBPB and UBCB control temporal and spatial activity of MEKKα differentially by degradation and/or processing and UBPB functions genetically to potentiate prespore cell differentiation. Whether this is solely through its effect on MEKKα or by controlling other proteins as well is not known. Down-regulation of MEKKα activity via ubiquitination through UBCB and ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis may be important for terminal differentiation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and development

The wild-type Dictyostelium cells, strain KAx-3, were grown and transformed using standard techniques (Nellen et al. 1987). Clonal isolates of non-drug-resistant strains were selected by plating clonally on SM plates in association with Klebsiella aerogenes as a food source. Clonal isolates carrying MEKKα expression constructs were transformed using G418 as a selectable marker and clonal isolates were selected on DM plates in association with Escherichia coli B/r carrying neomycin resistance (Hughes et al. 1992). Morphology was examined by plating cells at different densities on nonnutrient agar plates containing 12 mm Na/KPO4 (pH 6.1).

Molecular biology

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cloning of MEKKα was performed using sense [GA(A/G)(C/T)TIATGGCIGTIAA(A/G)C] and antisense [TTIGCICC(T/C)TTIAT(A/G)TCI C(G/T)(A/G)TG] degenerate primers to prime genomic DNA of KAx-3. Using one of the PCR products as a probe, a λZAP cDNA library was screened as described previously (Schnitzler et al. 1994) and cDNA clones were isolated and sequenced. The plasmid for homologous recombination was constructed by insertion of the Dictyostelium THY1 gene cassette into the MEKKα open reading frame (ORF) at the PvuII site located 1136 bp downstream from the start codon of MEKKα cDNA subcloned into pSP72 (XhoI/BglII). This construct was linearized with XhoI and EcoRV, electroporated into the thymidine auxotrophic strain JH10, and transformants were selected and screened for disruption of the MEKKα by genomic DNA blot analysis as described previously (Nellen et al. 1987). Transformants were selected and screened for disruption of the gene encoding MEKKα by Southern blot analysis. Site-directed mutagenesis to create a dominant-negative mutant of MEKKα was performed using the Transformer Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Clontech with mutation primer (5′-TTTGCTGTTGCACAATTAGAAATCG-3′). The construct containing site-directed mutants was sequenced to confirm the nucleotide substitutions and the absence of other mutations. RNA blots were done as described previously (Mann et al. 1987). All MEKKα constructs were expressed in Dictyostelium as stable G418-resistant transformants downstream from the Act15, Discoidin, prespore-specific SP60, or prestalk-specific ecmA promoters as described previously (Dynes et al. 1994). For the expression of myc-tagged WD40 in the pDXA3C vector, PCR was done with sense (5′-GTTTTGGATCCAAAATGGCAACAGCACAACCACCATGGT-3′) and antisense (5′-GTTTTCTCGAGTATCAATACTCCAAATTTTTACAAGTTTATC-3′). The PCR product was cut with BamHI/XhoI and subcloned into a pDXA-3C vector carrying a myc-epitope sequence. Flag-tagged MEKKα was created by performing PCR with sense (5′-GTTTTAGATCTAAAATGGACTACAAGGACGATGACAAGATGTCATGGTTGAATAATCCTTCTC-3′) and antisense (5′-CTTGTGACATATGTGA TGGTATATTTG-3′) primers. The PCR product was cut with BamHI/NcoI and ligated into pDXA-3C in association with an NcoI/XhoI fragment of MEKKαDN. The plasmid for homologous recombination of UBPB was constructed by insertion of a blasticidin-resistance gene cassette into the UBPB ORF at the AflIII site. This construct was linearized with EcoRI and EcoRV, electroporated into the KAx-3 strain, and transformants were selected and screened for disruption of the UBPB by genomic DNA blot analysis. MEKKα and MEKKαΔWD overexpression constructs were made by cloning the XhoI or XhoI/ClaI fragment of a 3–1 cDNA clone into DIP-a.

Analysis of morphology and β-galactosidase staining

Cells grown to mid-log phase in shaking cultures of HL5 medium were washed in 12 mm Na/KPO4 buffer (pH 6.1), resuspended in phosphate buffer at 2 × 107 cells, and spread on nonnutrient plates for development. For β-galactosidase staining, cells were developed on nitrocellulose filters resting on top of nonnutrient plates and then stained as described previously (Mann et al. 1994).

Screening of the yeast two-hybrid system

The yeast two-hybrid system developed in the laboratory of Roger Brent was used and screened as described previously (Gyuris et al. 1993; Lee et al. 1997). An NcoI/XhoI fragment of MEKKα was subcloned into pEG202, a bait vector. Approximately 0.8 × 106 independent library clones were obtained and screened for a β-galactosidase activity. Nine positive clones were obtained after the primary and secondary screenings.

Western blot and indirect immunofluorescence staining

Cells harvested at various developmental time points were washed, solubilized with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris at pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF), and heated at 100°C for 5 min. The protein content of each extract was measured with the BioRad protein assay kit. Twenty micrograms of protein per lane were resolved on either 8% or 10% gels, transferred onto PVDF membrane, and blots were processed by standard procedures (Harlow and Lane 1988). Bound antibody was detected with the ECL Western blotting kit (Amersham). Monoclonal anti-myc antibody, 9E10, was a generous gift of Beverly Errede (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill). Monoclonal anti-Flag antibody was obtained from Kodak. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were starved in 12 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.2) for >5 hr and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 5 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, washed, and incubated with 1.4 μg/ml anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20 for 1 hr. Cells were washed in 0.5% BSA containing PBS and incubated with FITC-labeled anti-mouse antibodies for 1 hr. After washing, cells were observed with a 60× oil immersion lens on a Nikon Microphot-FX microscope. Images were captured with a Photometrics Sensys camera and IP Lab Spectrum software. The GenBank accession number for MEKKα (mkka) is AF093689 and for ubpB is AF093690.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Randy Hampton (University of California at San Diego) for valuable discussions on ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, and to Beverly Errede (University of North Carolina) and Laurence Aubry and Jason Brown (UCSD), for helpful discussions and reading the manuscript critically. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants to R.A.F.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL rafirtel@ucsd.edu; FAX (619) 534-7073.

References

- Abe K, Yanagisawa K. A new class of rapid developing mutants in Dictyostelium discoideum: Implications for cyclic AMP metabolism and cell differentiation. Dev Biol. 1983;95:200–210. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Early A, Siegert F, Weijer C, Williams J. Patterns of cell movement within the Dictyostelium slug revealed by cell type-specific, surface labeling of living cells. Cell. 1994;77:687–699. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon A. Regulation of B-type cyclin proteolysis by Cdc28-associated kinases in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1997;16:2693–2702. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon A, Irniger S, Nasmyth K. Closing the cell cycle circle in yeast: G2 cyclin proteolysis initiated at mitosis persists until the activation of G1 cyclins in the next cycle. Cell. 1994;77:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T, Gamper M, Early A, Fukuzawa M, Abe Y, Kawata T, Kim E, Firtel RA, Williams JG. Developmentally and spatially regulated activation of a Dictyostelium STAT protein by a serpentine receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:4018–4028. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint-Kurti P, Ginsberg G, Rivero-Lezcano O, Kimmel A R. rZIP, a RING-leucine zipper protein that regulates cell fate determination during Dictyostelium development. Development. 1997;124:1203–1213. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider T, Vasiev B, Weijer CJ. A model for cell movement during Dictyostelium mound formation. J Theor Biol. 1997;189:41–51. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Insall R, Devreotes P. Signaling through chemoattractant receptors in Dictyostelium. Trends Genet. 1996;12:52–57. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1994;79:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Nomura A, Mohanty S, Firtel RA. A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme is essential for developmental transitions in Dictyostelium. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1989–2002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynes JL, Clark AM, Shaulsky G, Kuspa A, Loomis WF, Firtel RA. LagC is required for cell–cell interactions that are essential for cell-type differentiation in Dictyostelium. Genes &Dev. 1994;8:948–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early A, Abe T, Williams J. Evidence for positional differentiation of prestalk cells and for a morphogenetic gradient in Dictyostelium. Cell. 1995;83:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early AE, Gaskell MJ, Traynor D, Williams JG. Two distinct populations of prestalk cells within the tip of the migratory Dictyostelium slug with differing fates at culmination. Development. 1993;118:353–362. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firtel RA. Integration of signaling information in controlling cell- fate decisions in Dictyostelium. Genes &Dev. 1995;9:1427–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firtel RA. Interacting signaling pathways controlling multicellular development in Dictyostelium. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:545–554. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins C, Maeda M, Firtel RA. Identification and functional analysis of a developmentally regulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase gene in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6996–7012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins C, Clark AM, Aubry L, Segall JE, Firtel RA. The Dictyostelium MAP kinase ERK2 regulates multiple, independent developmental pathways. Genes &Dev. 1996;10:118–128. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GT, Kimmel AR. Autonomous and nonautonomous regulation of axis formation by antagonistic signaling via 7-span cAMP receptors and GSK3 in Dictyostelium. Genes &Dev. 1997;11:2112–2123. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GT, Gollop R, Yu YM, Louis JM, Saxe CL, Kimmel AR. The regulation of Dictyostelium development by transmembrane signalling. J Euk Microbiol. 1995;42:200–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstroh L, Firtel RA. A spatial gradient of expresssion of a cAMP-regulated prespore cell type-specific gene in Dictyostelium. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:596–612. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Firtel RA. The homeobox-containing gene Wariai regulates anterior-posterior patterning and cell-type homeostasis in Dictyostelium. Development. 1998;125:313–325. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood AJ, Plyte SE, Woodgett J, Strutt H, Kay RR. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 regulates cell fate in Dictyostelium. Cell. 1995;80:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin, proteasomes, and the regulation of intracellular protein degradation. Curr Biol. 1995;7:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JE, Podgorski GJ, Welker DL. Selection of Dictyostelium discoideum transformants and analysis of vector maintenance using live bacteria resistant to G418. Plasmid. 1992;28:46–60. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(92)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawata T, Shevchenko A, Fukuzawa M, Jermyn KA, Totty NF, Zhukovskaya NV, Sterling AE, Mann M, Williams JG. SH2 signaling in a lower eukaryote: A STAT protein that regulates stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Cell. 1997;89:909–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RR. Cell differentiation and patterning in Dictyostelium. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:934–938. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90121-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krefft M, Voet L, Gregg JH, Williams KL. Use of a monoclonal antibody recognizing a cell surface determinant to distinguish prestalk and prespore cells of Dictyostelium discoideum slugs. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;88:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Escalante R, Firtel RA. A RAS GAP is essential for cytokinesis and spatial patterning in Dictyostelium. Development. 1997;124:983–996. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis WF. The development of Dictyostelium discoideum. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- ————— The development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1993;28:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Gamper M, Parent C, Firtel RA. The Dictyostelium MAP kinase kinase DdMEK1 regulates chemotaxis and is essential for chemoattractant-mediated activation of guanylyl cyclase. EMBO J. 1997;16:4317–4332. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann SKO, Datta S, Howard P, Hjorth A, Reymond C, Silan CM, Firtel RA. Cyclic AMP regulation of gene expression during Dictyostelium development. In: Firtel RA, Davidson EH, editors. Molecular approaches to developmental biology. New York, NY: A.R. Liss; 1987. pp. 303–328. [Google Scholar]

- Mann SKO, Devreotes PN, Eliott S, Jermyn K, Kuspa A, Fechheimer M, Furukawa R, Parent CA, Segall J, Shaulsky G, Vardy PH, Williams J, Williams KL, Firtel RA. Cell biological, molecular genetic, and biochemical methods to examine Dictyostelium. In: Celis JE, editor. Cell biology: A laboratory handbook. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 412–451. [Google Scholar]

- Mann SKO, Brown JM, Briscoe C, Parent C, Pitt G, Devreotes PN, Firtel RA. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in controlling aggregation and post-aggregative development in Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1997;183:208–221. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellen W, Datta S, Reymond C, Sivertsen A, Mann S, Crowley T, Firtel RA. Molecular biology in Dictyostelium: Tools and applications. Meth Cell Biol. 1987;28:67–100. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper KB. Pseudoplasmodium formation and organization in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Elisha Mitchell Sci Soc. 1940;56:241–282. [Google Scholar]

- Reymond CD, Schaap P, Veron M, Williams JG. Dual role of cAMP during Dictyostelium development. Experientia. 1995;51:1166–1174. doi: 10.1007/BF01944734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler GR, Briscoe C, Brown JM, Firtel RA. Serpentine cAMP receptors may act through a G protein-independent pathway to induce postaggregative development in Dictyostelium. Cell. 1995;81:737–745. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler GR, Fischer WH, Firtel RA. Cloning and characterization of the G-box binding factor, an essential component of the developmental switch between early and late development in Dictyostelium. Genes &Dev. 1994;8:502–514. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segall JE, Kuspa A, Shaulsky G, Ecke M, Maeda M, Gaskins C, Firtel RA. A MAP kinase necessary for receptor-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:405–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert W, Futcher B, Jentsch S. Role of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme in degradation of S- and M-phase cyclins. Nature. 1995;373:78–81. doi: 10.1038/373078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert F, Weijer CJ. Spiral and concentric waves organize multicellular Dictyostelium mounds. Curr Biol. 1995;5:937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MN, Pelegrini O, Veron M, Kay RR. Mutation of protein kinase-A causes heterochronic development of Dictyostelium. Nature. 1992;356:171–172. doi: 10.1038/356171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D, Craig KL, Tyers M, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell. 1997;91:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld J. A study of pstB cells during Dictyostelium migration and culmination reveals a unidirectional cell type conversion process. Wm Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1992;201:354–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00365123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surana U, Robitsch H, Price C, Schuster T, Fitch I, Futcher A, Nasmyth K. The role of CDC28 and cyclins during mitosis in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991;65:145–161. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90416-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Kuras L, Barbey R, Cherest H, Blaiseau PL, Surdin-Kerjan Y. Met30p, a yeast transcriptional inhibitor that responds to S-adenosylmethionine, is an essential protein with WD40 repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6526–6534. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky A. The ubiquitin system. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:383–387. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Morphogensis in Dictyostelium: New twists to a not-so-old tale. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:426–431. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)90044-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]