Abstract

Sister-chromatid cohesion is essential for the faithful segregation of chromosomes during cell division. Recently biochemical analysis with Xenopus extracts suggests that cohesion is established during S phase by a cohesion complex but that other proteins must maintain it in mitosis. The Drosophila melanogaster MEI-S332 protein is present on centromeres in mitosis and meiosis and is essential for cohesion at the centromeres in meiosis II. Here, we analyze the timing of MEI-S332 assembly onto centromeres and the functional domains of the MEI-S332 protein. We find that MEI-S332 is first detectable on chromosomes during prometaphase, and this localization is independent of microtubules. MEI-S332 contains two separable functional domains, as mutations within these domains show intragenic complementation. The carboxy-terminal basic region is required for chromosomal localization. The amino-terminal coiled-coil domain may facilitate protein–protein interactions between MEI-S332 and male meiotic proteins. MEI-S332 interacts with itself in the yeast two-hybrid assay and in immunoprecipitates from Drosophila oocyte and embryo extracts. Thus it appears that MEI-S332 assembles into a multimeric protein complex that localizes to centromeric regions during prometaphase and is required for the maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion until anaphase, rather than its establishment in S phase.

Keywords: Sister-chromatid cohesion, mitosis, meiosis, centromere

Accurate segregation of the genetic material is one of the most fundamental and essential cellular processes. Errors in chromosome segregation during mitosis or meiosis result in aneuploidy, which is associated with tumorigenesis, miscarriages, and congenital disorders such as Down syndrome. Several events must be linked and coordinated to occur in a timely manner to ensure accurate segregation of chromosomes. First, cohesion between duplicated sister chromatids must be established during or immediately after DNA replication. Second, the dispersed interphase chromosomes must condense to facilitate chromosomal movement during segregation. Third, during mitotic and meiotic spindle formation and chromosome congression, sister-chromatid cohesion must be maintained stably to resist the poleward pulling forces as kinetochores engage in microtubule interaction.

To ensure proper chromosome segregation, cohesion must be established between sister chromatids, and the simplest way to ensure the attachments are indeed between sisters would be to make these connections during or immediately after DNA replication. Results from FISH experiments in Saccharmomyces cerevisiae indicate that sister-chromatid cohesion is established during S phase (Guacci et al. 1994). Recent identification of S. cerevisiae proteins necessary for sister-chromatid cohesion (Guacci et al. 1997; Michaelis et al. 1997) provides additional evidence that sister-chromatid cohesion is established during S phase. Guacci et al. (1997) demonstrated that one of these proteins, Mcd1p/Scc1p, physically associates with a member of the SMC family, SMC1, and that its levels are cell-cycle regulated, peaking in S phase, declining by late S phase, and remaining constant through telophase. Michaelis et al. (1997) found that Mcd1p/Scc1p associates with chromatin in late G1/early S phase and dissociates from it at the onset of anaphase. Recently it was shown that Scc1p must associate with sister chromatids in S phase to ensure cohesion. Although Scc1p can asssemble onto chromosomes in G2 phase, chromosome nondisjunction nevertheless occurs if cells undergo S phase in the absence of Scc1p (Uhlmann and Nasmyth 1998).

Upon entry into mitosis, in prophase, chromosomes compact 5- to 10-fold in mammalian cells or 2-fold in yeast cells (for review, see Koshland and Strunnikov 1996). The isolation, in multiple species, of mutants defective in mitotic chromosome condensation demonstrated that condensation is a necessary prerequisite for proper chromosome segregation. Mutations in the S. cerevisiae smc genes and in some of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe cut genes lead to a reduction in chromosome compaction during mitosis and phenotypes indicating defects in chromosome segregation (Saka et al. 1994; Strunnikov et al. 1995). Components of the condensation machinery, a 13S protein complex termed condensin, have also been identified in Xenopus (Hirano et al. 1997) and demonstrated to be required for both establishing and maintaining the condensation state of mitotic chromosomes (Hirano and Mitchison 1994; Hirano et al. 1997).

During and after condensation, the sister-chromatid cohesion previously established must be maintained until the metaphase/anaphase transition. The physical association between sister chromatids appears to counteract the poleward forces, creating tension that keeps the sister chromatids on the metaphase plate until their separation at the onset of anaphase (for review, see Miyazaki and Orr-Weaver 1994). Sister-chromatid cohesion also likely plays a role in sister kinetochore orientation. By restricting the movement of sister chromatids via physical association, sister-chromatid cohesion forces the sister kinetochores to face opposite spindle poles and establish the bipolar attachment to the spindle microtubules during mitosis and meiosis II (for review, see Bickel and Orr-Weaver 1996).

Recent work in Xenopus identified a cohesin complex consisting of homologs of the yeast SMC1 and SMC3 proteins as well as a homolog of S. cerevisiae Mcd1p/Scc1p (Rad21p in Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Losada et al. 1998). In contrast to yeast, in Xenopus extracts, the cohesin complex does not persist through mitosis, rather it dissociates at the onset of mitosis and is replaced by the condensin complex (Losada et al. 1998). Although the condensin complex could, in theory, maintain cohesion until anaphase, mutations in the S. pombe or S. cerevisiae components of the condensin complex do not exhibit defects in sister-chromatid cohesion, making it possible that condensins are not sufficient for cohesion (Saka et al. 1994; Strunnikov et al. 1995). Therefore, a function to maintain cohesion during mitosis after the cohesin complex has dissociated from the chromosomes would be particularly important at the sister centromeres, which are subjected to microtubule pulling forces.

The Drosophila MEI-S332 protein is required for cohesion between the centromeres of the sister chromatids. Mutations in the mei-S332 gene lead to precocious separation of sister chromatids in late anaphase I, resulting in chromosome loss and mis-segregation in meiosis II (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). They also seem to cause a weakening of the centromeric cohesion in mitotic cells, indicating a role for MEI-S332 during mitosis (H. LeBlanc, T.T.-L. Tang, J. Wu, and T.L. Orr-Weaver, in prep.). Although mei-S332 mutants are defective in sister-chromatid cohesion, they are not affected in chromosome condensation (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). Furthermore, the MEI-S332 protein localizes to the centromeric regions during meiosis and mitosis while it dissociates from the chromosomes at the onset of anaphase when sister chromatids separate from one another (Kerrebrock et al. 1995; Moore et al. 1998).

The mutant phenotypes and the cellular localization of the MEI-S332 protein make it a strong candidate to maintain sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromere. Although previous mutant analysis in meiosis showed that MEI-S332 is essential at the centromeres, it did not address whether MEI-S332 is involved in establishing or maintaining cohesion. In addition, because MEI-S332 acts at the centromeres, an important step in understanding its mechanism of action is to determine the relationship between MEI-S332 localization, microtubule attachment, and spindle assembly. Thus, in this study, we used cytological, genetic, and biochemical experiments to demonstrate that MEI-S332 functions to maintain rather than establish sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromeres. MEI-S332 assembles onto condensed chromosomes during prometaphase independent of intact microtubules, and its chromosomal localization requires the carboxy-terminal basic region.

Results

MEI-S332 assembles onto condensed chromosomes during prometaphase

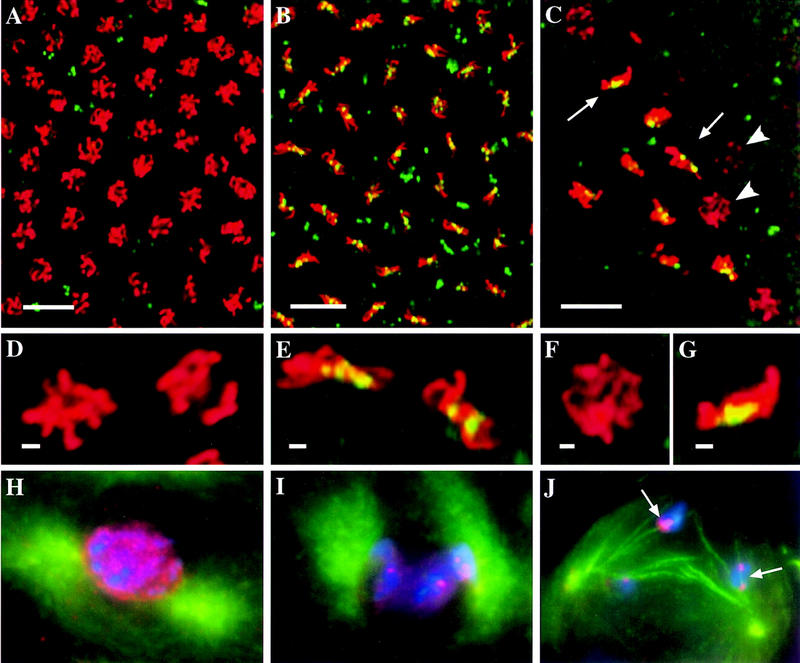

To determine whether MEI-S332 is involved in the establishment or maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion, we investigated the onset of MEI-S332 assembly onto chromosomes by double-labeling syncytial blastoderm and postblastoderm embryos with anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (anti-phospho H3) and anti-full-length MEI-S332 antibodies (for a review of Drosophila embryogenesis, see Foe et al. 1993). With anti-phospho H3 antibodies, Hendzel et al. (1997) have shown that mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates in pericentromeric heterochromatin in late G2 interphase cells and spreads throughout the condensing chromosomes, completing just prior to the formation of prophase chromosomes. By comparing the timing of MEI-S332 chromosomal localization relative to histone H3 phosphorylation and hence, to chromosome condensation, we found that MEI-S332 assembled onto the chromosomes during prometaphase (Fig. 1A–G).

Figure 1.

MEI-S332 assembles onto mitotic and meiotic chromosomes during prometaphase. (A–C) Embryos doubled-labeled with anti-MEI-S332 (green) and anti-phospho H3 (red) antibodies. (Yellow) Areas of overlap. (H–J) Spermatocytes triple-labeled with DAPI (blue), anti-MEI-S332 (red) and anti-tubulin (green) antibodies. (A,B) Images from the same S–M syncytial blastoderm embryo. In a portion of the nuclei, MEI-S332 is not detected on the chromosomes stained with anti-phospho H3; these chromosomes do not appear to be congressing (A). In nuclei where MEI-S332 is observed on the chromosomes, the chromosomes seem to be congressing (B). (C) A portion of a mitotic domain in a S–G2–M postblastoderm embryo demonstrates that MEI-S332 is not observed on the chromosomes in some of the nuclei that have already initiated histone H3 phosphorylation (arrowheads). MEI-S332 is seen on chromosomes that appear to be congressing (arrows). (D,E) Enlargements of two nuclei from A and B, respectively. (F,G) Enlargements of two nuclei shown in C. (H) In late meiotic prophase I, tubulin staining reveals two centrosomes that have not yet migrated completely to opposite sides of the nucleus, and the chromosomes appear to be condensing. MEI-S332 seems to localize in a punctate fashion inside the nucleus (stage M1a; Cenci et al. 1994). (I) In this prometaphase I spermatocyte (stage M1b; Cenci et al. 1994), the chromosomes have condensed further, and the centrosomes have completed their migration to opposite sides of the nucleus. MEI-S332 is now detected on the chromosomes in distinct foci. (J) The nuclear–cytoplasmic demarcation has disappeared in this M2 (Cenci et al. 1994) prometaphase I spermatocyte, allowing microtubule interactions with the kinetochores. MEI–S332 is observed in two foci on each bivalent, corresponding to two pairs of sister centromeres in each bivalent. Microtubule fibers emanating from one centrosome can be clearly seen colocalizing with both MEI-S332 foci on a bivalent (arrows), indicating that bipolar attachment has not yet been established. (A–C) Bars, ∼10 μm; (D–G) bars, ∼1 μm.

MEI-S332 became visible on the chromosomes only when they appeared to be congressing, and its signal on the chromosomes was most obvious at metaphase. Similar results were obtained with different MEI-S332 antibodies that recognize only a carboxy-terminal 15-mer epitope (data not shown and Moore et al. 1998). While we cannot exclude the possibility that MEI-S332 is present on chromosomes earlier than prometaphase but is not detectable by either the anti-full-length or the anti-peptide antibodies, it is unlikely. On the basis of DNA morphology and the phosphorylated histone H3 staining, the degree of chromosome compaction appears to be the same in prophase and prometaphase, and hence, if MEI-S332 were on the chromosomes during earlier cell-cycle stages, we should have detected it.

It was also important to determine when MEI-S332 assembles onto the chromosomes in meiosis. Previous analysis of oocytes showed that MEI-S332 does not localize on the chromosomes in the prophase I karyosome (Moore et al. 1998). Instead, it appeared to assemble at a time when the nuclear envelope breaks down and the spindle begins to form. However, cytological analysis with oocytes is limited in that individual chromosomes are not distinguishable in the chromosome mass until egg activation and the beginning of anaphase I movement. Therefore, we addressed this issue using spermatocytes where individual bivalents, pairs of homologous chromosomes, can be visualized. In addition, in this current study of MEI-S332 localization, we used antibodies that specifically recognize MEI-S332 (see Materials and Methods), which greatly enhanced the sensitivity of detection relative to the green fluorescence protein (GFP) used in the previous studies (Kerrebrock et al. 1995; Moore et al. 1998).

Triple-labeling of spermatocytes with anti-MEI-S332 and anti-tubulin antibodies and a DNA dye, DAPI, demonstrated that MEI-S332 exhibited nuclear localization at late meiotic prophase I (Fig. 1H). At the onset of prometaphase I, it became detectable in a few foci on the condensing chromosomes (Fig. 1I). By the time the nuclear/cytoplasmic separation was no longer visible in prometaphase I, MEI-S332 was clearly seen to localize in two dots on each bivalent (Fig. 1J).

These immunofluorescence results from embryos and spermatocytes showed that MEI-S332 is not detected on the chromosomes immediately after DNA replication when cohesion has been established and indicate that MEI-S332 is involved in the maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion.

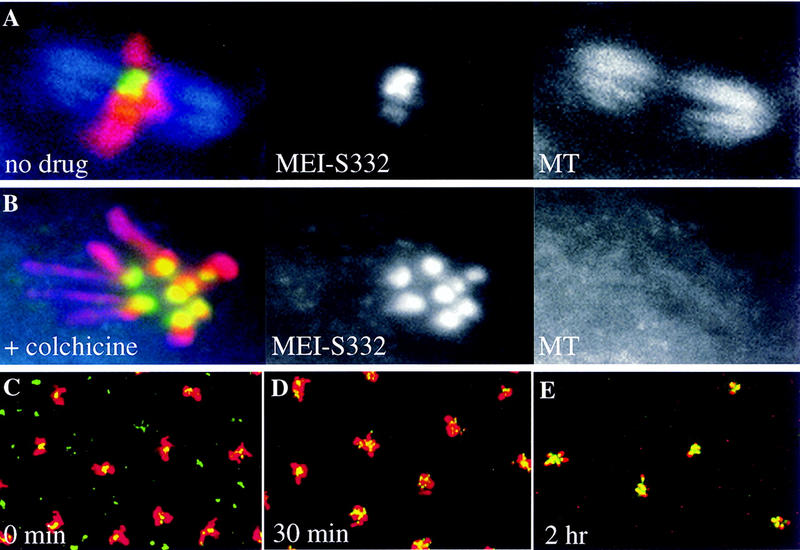

Spindle assembly is not required for MEI-S332 localization

In meiosis and mitosis, chromosomal localization of MEI-S332 correlated with the onset of spindle assembly and chromosome movement or congression, suggesting that MEI-S332 may not assemble onto the chromosomes until microtubule binding at the kinetochores. Additional cohesion proteins might be necessary when poleward forces that could separate the sister chromatids are exerted on the kinetochores. To examine the relationship between MEI-S332 and spindle forces, we tested whether the spindle was required for MEI-S332 localization.

First, we looked at whether the MEI-S332 molecules that had already assembled onto the centromeres would remain in the absence of intact microtubules. We treated embryos with a short incubation (30 min) of colchicine, a microtubule depolymerizing drug, followed by fixation and staining with anti-MEI-S332 and anti-phospho H3 antibodies. In both syncytial blastoderm S–M and postblastoderm S–G2–M embryos, MEI-S332 still localized on the chromosomes when the microtubules had been depolymerized (Fig. 2A,B; and data not shown). Anti-tubulin staining confirmed that colchicine had destabilized the spindle in these embryos (Fig. 2B). This result shows that microtubules are not required for maintaining MEI-S332 localization on the centromeres.

Figure 2.

MEI-S332 localizes to chromosomes independent of microtubules. A collection of 2-hr wild-type embryos was incubated for 30 min without (A) or with (B) colchicine (100 μg/ml), fixed, and stained with DAPI, anti-MEI-S332 and anti-tubulin antibodies. Representative nuclei from S–M syncytial blastoderm embryos are shown. Artificial colors are used: (red) DNA; (green) MEI-S332; and (blue) spindle. Under colchicine treatment, chromosomes are more spread out, MEI-S332 is seen as eight dots, corresponding to the four pairs of homologous chromosomes in Drosophila, and a metaphase plate is not visible. (C–E) Embryos untreated or treated with colchichine (100 μg/ml) for 30 min or 2 hr, fixed, and stained with anti-MEI-S332 and anti-phospho H3 antibodies. More MEI-S332 (green) signals are detected on chromosomes (red) in embryos that were treated with colchicine for 2 hr (E) than ones treated for 30 min (D) or ones that were not treated (C). With prolonged colchicine treatment (E) the chromosomes became hypercondensed.

To test whether MEI-S332 needs microtubules to assemble onto the centromeres, we incubated early embryos longer with colchicine (2 hr). In the early embryos, the cell cycles are very rapid, between 8 and 18 min, so all nuclei would enter mitosis during a 2-hr colchicine treatment. Thus, we could determine whether microtubules were necessary for MEI-S332 assembly by seeing whether all nuclei in colchicine-treated embryos had MEI-S332 localized on the chromosomes. Indeed, we still observed MEI-S332 on the mitotic chromosomes in all the nuclei after the longer treatment with colchicine (Fig. 2E). Again, anti-tubulin staining confirmed that microtubules were depolymerized by colchicine (data not shown). MEI-S332 signal and the apparent levels on the chromosomes consistently was higher in embryos incubated longer in colchicine (Fig. 2, cf. E to C and D).

In addition to showing that intact microtubules are dispensible for MEI-S332 assembly and maintenance on centromeres, these results suggest that there is a period of time during which MEI-S332 can assemble onto the chromosomes. This period is immediately after prophase but prior to microtubule binding to the kinetochores. Colchicine treatment arrests cells in this period of time, and, consequently, more MEI-S332 is able to assemble.

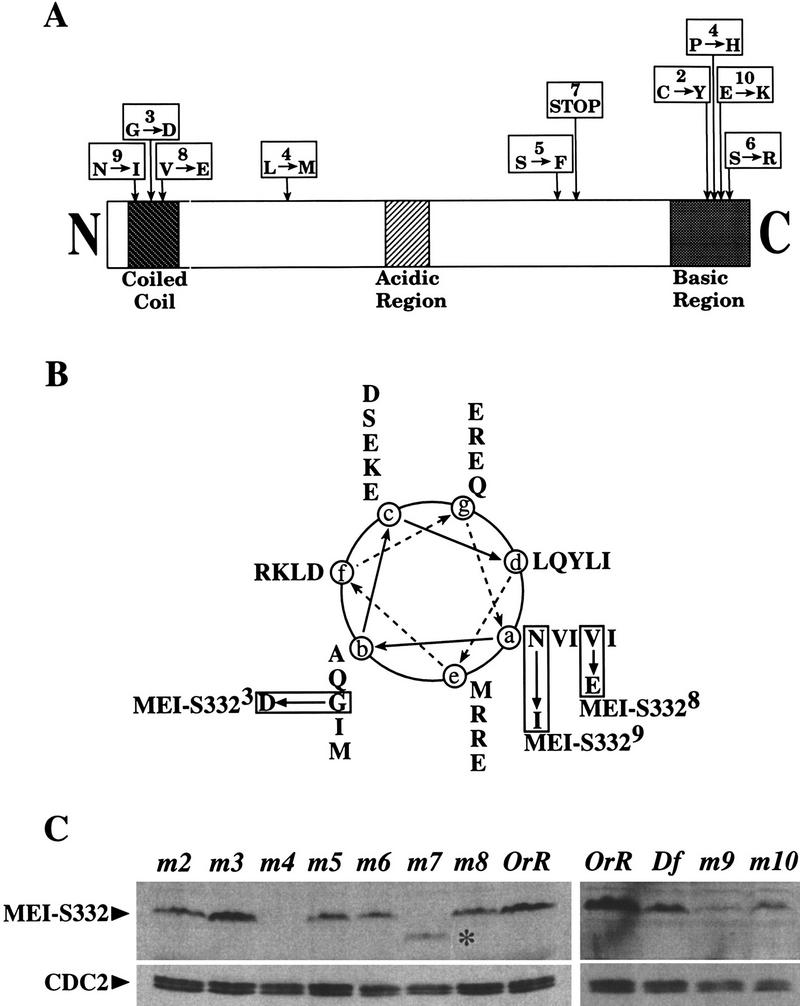

Mutations in MEI-S332 highlight two domains

Knowing the timing of MEI-S332 assembly onto chromosomes, we next defined the domain(s) of the MEI-S332 protein necessary for its chromosomal localization. Mutations in mei-S332 highlight two distinct domains of MEI-S332, a predicted coiled-coil domain near the amino terminus and a basic region at the carboxyl terminus of the protein (Kerrebrock et al. 1995; Fig. 3A). Furthermore, mutations in the predicted coiled-coil domains are male-predominant alleles, because they cause high frequencies of chromosome loss and missegregation in male meiosis but low frequencies in female meiosis (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). In contrast, mutations in the basic region are female-predominant alleles and result in a stronger missegregation phenotype in females than in males.

Figure 3.

Amino acid alterations in MEI-S332. (A) The MEI-S332 protein has several distinct structural features. There are 10 alleles of mei-S332, most of which map to two domains, the amino-terminal predicted coiled coil and the carboxy-terminal basic region. (Downward arrows) Relative positions of the mutations. Numbers in the boxes designate the allele numbers; below are the amino acid changes. (B) The predicted coiled coil of MEI-S332 is represented in this helical wheel diagram showing the amino acids corresponding to positions a–e in the coil. Both mei-S3328 and mei-S3329 mutations are located at position a in the hydrophobic face of the predicted coiled coil, but mei-S3323 is more proximal to the hydrophilic face of the coil at position b. (C) Immunoblots of ovary extracts from mei-S332 mutant females bound to anti-MEI-S332 antibodies reveal the stability of the mutant forms of the MEI-S332 protein. CDC2 levels are shown as the loading control. Except for the truncated, faster-migrating MEI-S3327 (*), mutant forms of the MEI-S332 protein do not exhibit any altered mobility rate in gels. They are designated by m followed by a corresponding allele number. The relative protein levels of MEI-S3329 and MEI-S33210 should be compared to that in ovaries from females carrying one copy of the mei-S332 gene (Df; see Materials and Methods).

We recovered two new alleles of mei-S332 in a noncomplementation screen with mei-S3321 (Bickel et al. 1997). One allele, mei-S3329, is a mutation of asparagine 13 to isoleucine at the start of the predicted coiled-coil, and the other, mei-S33210, is a change from glutamate to lysine at residue 382 in the basic region (Fig. 3A,B). We also sequenced the weakest allele, mei-S3325 and found that it changes serine 277 to phenylalanine.

Because mei-S3329 and mei-S33210 map to the coiled-coil domain and the basic region, respectively, we predicted that they would exhibit sex-predominant chromosome segregation phenotypes. By standard genetic tests (see Materials and Methods) we found that mei-S3329 and mei-S33210 mutations resulted in high frequencies of chromosome loss and mis-segregation in both male and female meiosis II (Tables 1 and 2). Three previously described alleles, mei-S3326, mei-S3327, and mei-S3328, were included in the tests as controls (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). Furthermore, in males, mei-S3329 caused a stronger mis-segregation phenotype than mei-S33210 (Table 1). On the other hand, in females, mei-S33210 resulted in a higher mis-segregation frequency than mei-S3329 (Table 2). Thus, the genetic results were consistent with our previous observation and strongly suggest that the amino-terminal coil domain plays a male-specific role whereas the carboxy-terminal basic region is more important in females.

Table 1.

Sex chromosome mis-segregation in males with the indicated allele over Df(2R)X58-6

| Allele

|

Percent regular sperma

|

Percent exceptional sperma

|

Total progeny

|

Total percent mis-segregation

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

X

|

Y(Y)

|

O

|

XY(Y)

|

XX

|

XXY(Y)

|

|||

| mei-S3329 | 34.2 (480) | 26.5 (373) | 26.7 (375) | 1.6 (22) | 11.0 (155) | 0.0 (0) | 1405 | 39.3 |

| mei-S3327 | 41.1 (363) | 26.3 (232) | 23.9 (211) | 0.7 (6) | 8.0 (71) | 0.0 (0) | 883 | 32.6 |

| mei-S33210 | 39.4 (551) | 28.5 (398) | 21.0 (293) | 0.8 (11) | 10.3 (144) | 0.0 (0) | 1397 | 32.1 |

| mei-S3328 | 38.3 (415) | 31.8 (345) | 19.3 (209) | 0.6 (6) | 10.1 (109) | 0.0 (0) | 1084 | 29.9 |

| mei-S3326 | 52.0 (654) | 41.1 (517) | 5.2 (66) | 0.3 (4) | 1.4 (17) | 0.0 (0) | 1258 | 6.9 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of progeny counted.

Table 2.

Sex chromosome mis-segregation in females with the indicated allele over Df(2R)X58-6

|

Allele

|

Percent regular ovaa

|

Percent exceptional ovaa

|

Total progeny

|

Adjusted totalb

|

Total percent mis-segregation

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

X

|

O

|

XX

|

||||

| mei-S3327 | 42.3 (423) | 24.2 (121) | 33.2 (167) | 711 | 999 | 57.7 |

| mei-S33210 | 51.9 (710) | 33.6 (230) | 14.5 (99) | 1039 | 1368 | 48.1 |

| mei-S3326 | 52.6 (572) | 21.3 (116) | 26.1 (142) | 830 | 1088 | 47.4 |

| mei-S3329 | 55.2 (1034) | 25.5 (239) | 19.2 (180) | 1453 | 1872 | 44.8 |

| mei-S3328 | 74.7 (1072) | 8.8 (63) | 16.6 (119) | 1254 | 1436 | 25.3 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of progeny counted.

The total progeny is adjusted to correct for the recovery of only half of the total number of exceptional progeny.

Prior to testing the effects of these mutations on MEI-S332 localization in mitosis as well as in male and female meioses, we wanted to confirm that the mutant MEI-S332 proteins were stable. We were particularly interested in this for the two strong alleles, mei-S3324 and mei-S3327. Ovary extracts were prepared from mutant mei-S332 females, and immunoblots were bound to guinea pig anti-MEI-S332 antibodies (Fig. 3C). For alleles 2 through 8, ovaries were dissected from homozygous mutant females, whereas for alleles 9 and 10, ovaries were from mutant over deficiency females.

The results from these experiments revealed that we have a null allele of mei-S332, there is a stable truncated form of the protein, and that the mutant missense forms are stable. Specifically we found the following: (1) MEI-S3324 was completely absent from ovaries (Fig. 3C, lane 3) and could be considered as a null in females, consistent with previous genetic results (Kerrebrock et al. 1992); (2) the MEI-S3327 protein was seen as a stable and truncated protein by the use of the guinea pig antibodies generated against the full-length MEI-S332 protein (Fig. 3C, lane 6); (3) mutant MEI-S332 proteins were present in ovaries from mei-S3322, mei-S3325, mei-S3326, mei-S3328, mei-S3329, and mei-S33210 females, although with decreased levels (Fig. 3C, lanes 1,4,5,7,11,12); (4) MEI-S3323 appeared to be present in wild-type levels (Fig. 3C, lane 2); and (5) Western blots of testis extracts from mutant mei-S332 males showed similar results, except that MEI-S3324 was present at very low levels (data not shown). Again, this observation is consistent with previous genetic analysis (Kerrebrock et al. 1992); unlike in females, mei-S3324 did not behave genetically as a null in males.

The carboxy-terminal basic domain of MEI-S332 is required for chromosomal localization

We looked at the effect of mutations in the MEI-S332 basic region on the ability of the protein to localize onto meiotic and mitotic chromosomes. We were able to test the effects of amino acid substitutions using the mei-S3322, mei-S3326, and mei-S33210 alleles and to also examine the consequence of complete loss of the carboxy-terminal basic region with the truncation allele, mei-S3327 (Fig. 3A).

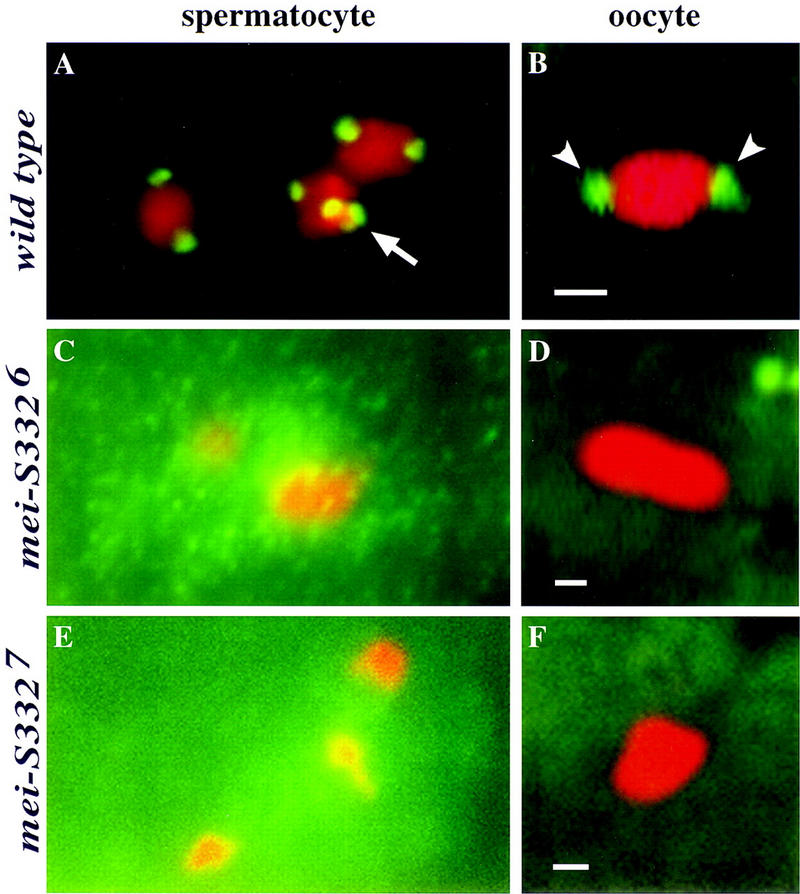

In both spermatocytes and oocytes, either amino acid substitution within or truncation prior to the basic domain ablated detectable MEI-S332 chromosomal localization. The wild-type pattern of localization was not observed with MEI-S3326 or MEI-S3327 mutant proteins in either spermatocytes or oocytes (Fig. 4, cf. A and B to C–F). Anti-tubulin staining on spermatocytes confirmed the stages of meiosis (data not shown). Failure of centromere localization was observed also with MEI-S3322 and MEI-S33210 mutant proteins (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Mutations in the carboxy-terminal basic region alter MEI-S332 localization in spermatocytes and oocytes. (Green) MEI-S332; (red) chromosomes. (A) Wild-type MEI-S332 protein localizes to two distinct foci on each bivalent in a prometaphase I spermatocyte. Each of these foci represents one pair of sister-chromatid centromeres in each homolog. All four chromosome bivalents can been seen here. The tiny fourth chromosome bivalent, which is often difficult to visualize, is seen clustered with a large bivalent (arrow). (B) In a metaphase I-arrested oocyte, wild-type MEI-S332 protein is seen on two opposite ends of the condensed karyosome (arrowheads). Unlike the foci in spermatocytes, these foci represent two clusters of sister-chromatid centromeres of all four chromosomes. (C) MEI-S3326 mutant protein fails to localize to the typical two foci on each bivalent in a prometaphase I spermatocyte. Three large bivalents can be seen clearly here. Instead, this mutant form of the protein seems to be concentrating around the chromosomes in the nucleus. Among all the spermatocytes (∼100 cells) examined in eight separate trials with either the rabbit carboxy-terminal peptide MEI-S332 antibodies (Moore et al. 1998) or the guinea pig full-length MEI-S332 antibodies (this study), MEI-S3326 protein has never been clearly observed on the chromosomes in the two-foci-per-bivalent fashion. (D) MEI-S3326 protein also has never been observed on the karyosome in metaphase I-arrested oocytes. (E,F) Deletion of the carboxy-terminal basic region ablates the ability of the MEI-S332 protein to localize properly. MEI-S3327 mutant protein is absent from the chromosomes in both prometaphase I spermatocyte (E) and metaphase I oocyte (F). Bars, ∼1 μm.

It was surprising that missense mutations in the basic region of MEI-S332 disrupted MEI-S332 chromosomal localization in spermatocytes, given that two of these alleles exhibit only weak defects in male meiosis. The cloud of MEI-S3326 signal concentrated around the chromosomes (Fig. 4C) leaves open the possibility that a small amount of the mutant protein localized onto the chromosomes and was capable of ensuring cohesion in males.

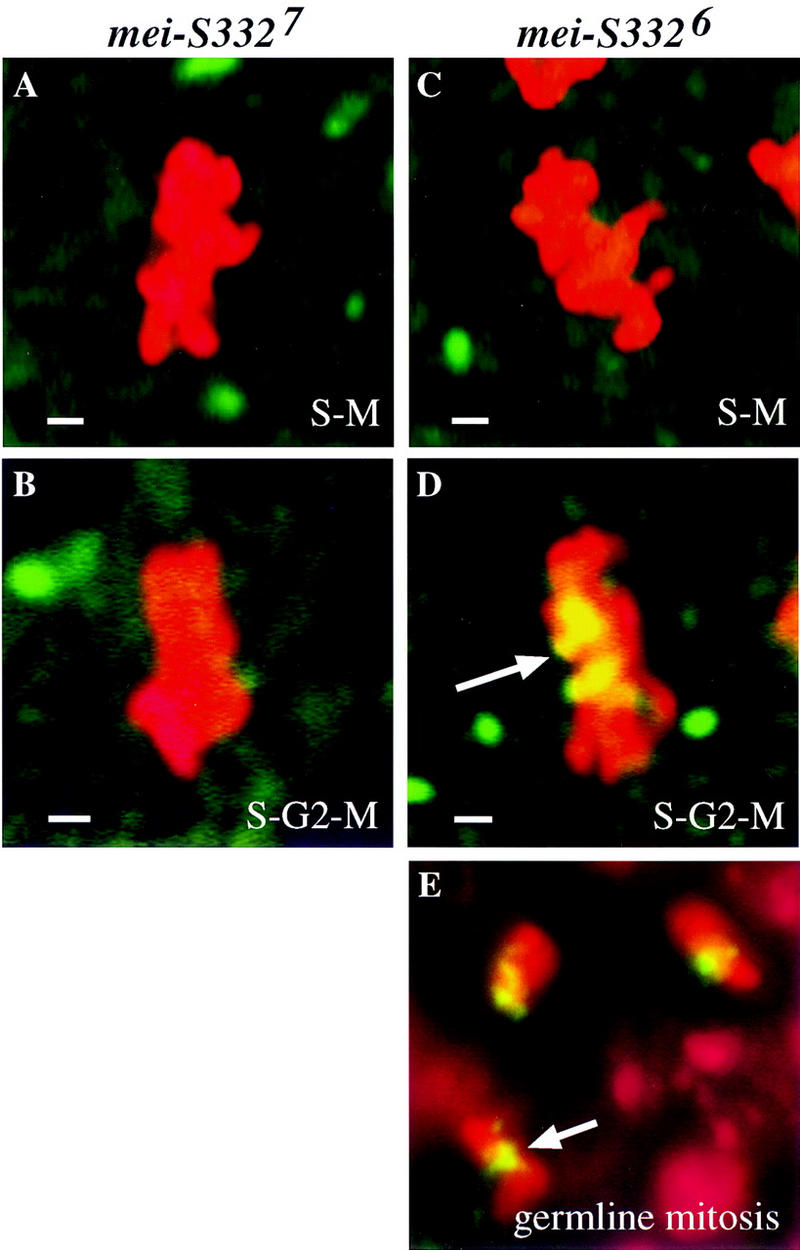

We examined the requirements for the carboxy-terminal basic region for mitotic chromosomal localization by staining mutant embryos. The truncated MEI-S3327 protein failed to localize during the S–M cycles and the postblastoderm divisions, demonstrating that the carboxyl terminus of the protein is essential for centromere localization in mitosis as well as meiosis (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Missense mutations in the carboxy-terminal basic region impede but do not preclude chromosomal localization. (Green) MEI-S332; (red) chromosomes; (yellow) areas of overlap. (A,B) Representative metaphase nuclei from a mei-S3327 S–M syncytial blastoderm embryo (A) and a S–G2–M postblastoderm embryo (B) are shown. MEI-S3327 is not detectable on the condensed chromosomes. (C) MEI-S3326 protein is not observed on metaphase chromosomes in S–M syncytial blastoderm embryos. (D) As the cell cycles lengthen with an addition of the G2 phase and a longer M phase in postblastoderm embryos, MEI-S3326 localizes to the condensed metaphase chromosomes (arrow). (E) In spermatogonial mitotic divisions with the canonical cell cycle, MEI-S3326 localizes to the condensed metaphase chromosomes. Chromosomes in embryos were visualized by use of anti-phospho H3 antibodies, and chromosomes in spermatogonial mitotic nuclei were stained with DAPI. Bars, ∼1 μm.

The analysis of MEI-S3326 protein in embryos gave unexpected results. No localization of MEI-S3326 was observed during the S–M cycles (Fig. 5C). However, in postblastoderm divisions, we observed MEI-S3326 localized to the mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 5D). The MEI-S3326 signals appeared dimmer and more diffuse than wild type. The ability of MEI-S3326 to localize correlated with the length of the cell cycle. The rapid S–M cycles at syncytial blastoderm stage lack a G2 phase and at most have an interphase of 13 min and mitosis of 4.5 min (Foe et al. 1993). The S–G2–M postblastoderm cycles, when MEI-S3326 did localize, have a G2 of 30 to >150 min (Edgar and O’Farrell 1989) and a mitosis of 10–60 min (Foe et al. 1993). We hypothesize that while deletion of the basic region ablates the ability of MEI-S332 to localize, missense mutations in the basic region only weaken it. Thus missense mutant proteins can localize given enough time. Consistent with this idea, we detected MEI-S3326 in spermatogonial mitotic divisions with the canonical cell cycle (Fig. 5E).

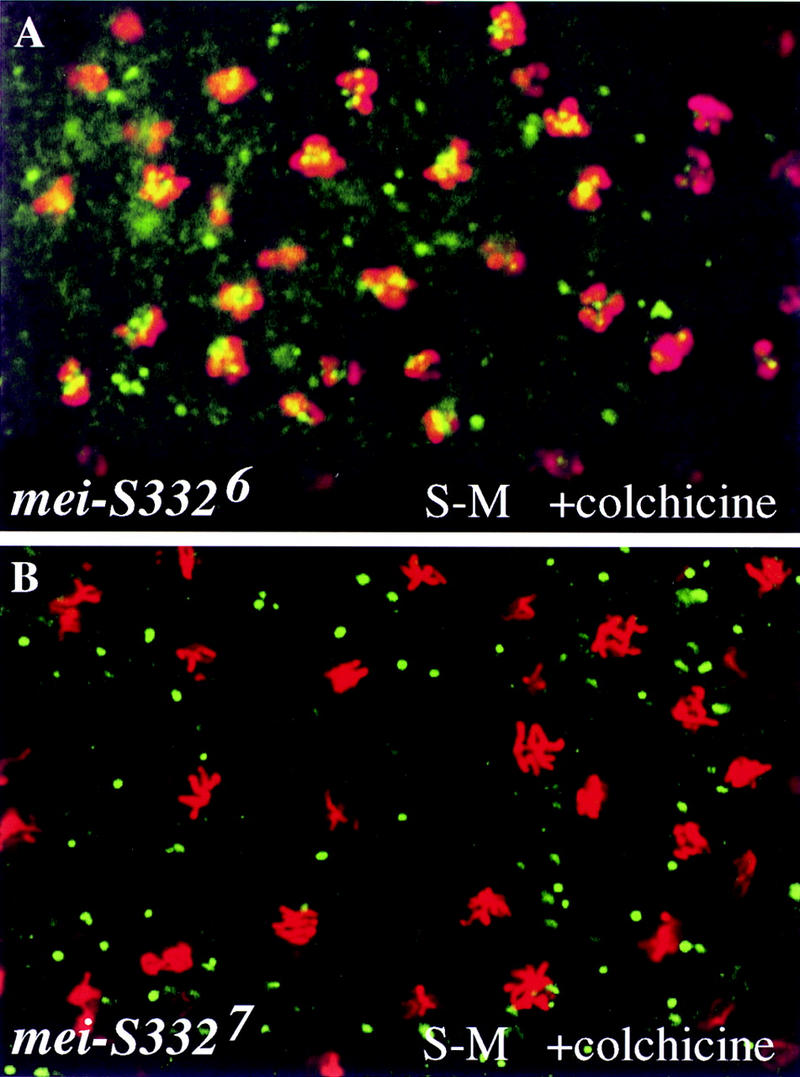

To test this hypothesis further, we provided the mutant proteins with an unlimited amount of time to assemble onto the centromeres by arresting the S–M cycles in prometaphase with colchicine. Whereas MEI-S3326 was not detected on the chromosomes in the syncytial blastoderm S–M cycles under normal conditions, it was seen on the chromosomes in these early cycles after the embryos had been treated with colchicine (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, MEI-S3327 still failed to localize to the chromosomes when prometaphase was arrested by colchicine (Fig. 6B). Therefore, the localization studies on MEI-S3326 and MEI-S3327 show that the carboxyl terminus is essential for centromere binding and that amino acid substitutions in the basic region impede but do not preclude chromosomal localization.

Figure 6.

MEI-S332 proteins with missense mutations in the carboxy-terminal basic region require more time to achieve chromosomal localization. Syncytial blastoderm (S–M) embryos from mei-S3326 (A) and mei-S3327 (B) females were treated with 100 μg/ml colchicine for 2 hr, fixed, and stained with anti-MEI-S332 (green) and anti-phospho H3 (red) antibodies.

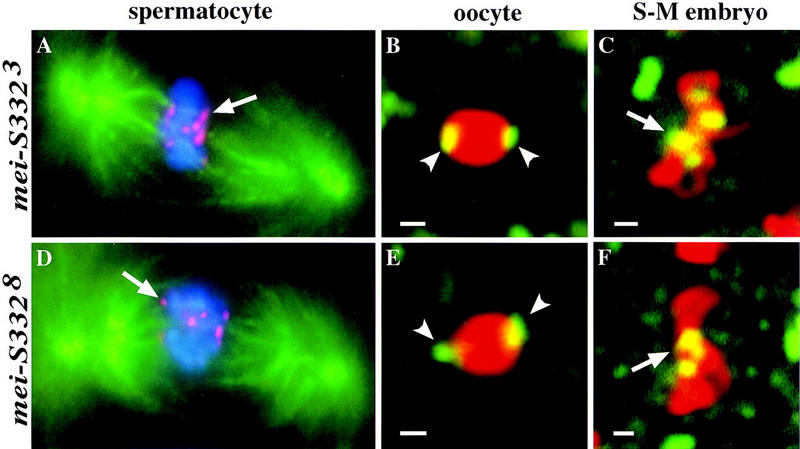

MEI-S332 proteins with alterations in the predicted coiled–coil domain localize to meiotic and mitotic chromosomes

Next, we tested the role of the predicted coiled–coil domain of MEI-S332 for chromosomal localization in meiosis and mitosis. In spermatocytes, oocytes, and the S–M cycles, both MEI-S3323 and MEI-S3328 mutant proteins localized normally to the centromeres (Fig. 7A–F). This was also true for postblastoderm and spermatogonial divisions (data not shown). The signals on the chromosomes were more intense for MEI-S3323 than MEI-S3328, most likely reflecting the endogenous mutant protein levels as revealed by Western blotting (Fig. 3C). We could not detect MEI-S3329 on the chromosomes in mei-S3329/Df(2R)X58-6 spermatocytes (data not shown), even in conditions under which we could see MEI-S332 chromosomal localization in Df(2R)X58-6/+ spermatocytes. One possibility is that the reduced levels of MEI-S3329 protein render it difficult to detect by immunofluorescence microscopy. Nevertheless, given the nature of mei-S3328 mutation, these results suggest that the predicted coiled–coil structure is not required for MEI-S332 chromosomal localization.

Figure 7.

MEI-S332 proteins with mutations in the predicted coiled-coil domain still localize to mitotic and meiotic chromosomes. (A,D) MEI-S332 is red, chromosomes stained by DAPI are blue, and the spindle is green. (B,C,E,F) MEI-S332 is green, and anti-phospho H3-stained chromosomes are red. (A) In metaphase I spermatocytes, MEI-S3323 mutant protein is observed on the chromosomes in eight foci corresponding to the eight pairs of sister-chromatid centromeres. Microtubules can be seen colocalizing with every MEI-S3323 dot (arrow). (B) MEI-S3323 mutant protein is also capable of localizing to the meiotic centromeric regions in oocytes. The pattern of localization resembles that of wild type (arrowheads; see Fig. 4B). (C) In S–M syncytial blastoderm embryos, MEI-S3323 localizes properly to the metaphase chromosomes. (D) A nonconservative amino acid substitution (valine to glutamate) in the hydrophobic face of the predicted coiled coil does not disrupt the ability of MEI-S332 to localize onto meiotic chromosomes in spermatocytes. Eight dots of MEI-S3328 are detected on the metaphase I chromosomes, each colocalizing with microtubules (arrow). (E) This amino acid change also fails to perturb chromosomal localization of MEI-S332 in metaphase I-arrested oocytes. Like the wild-type protein, MEI-S3328 localizes to opposite sides of the karyosome (arrowheads). (F) MEI-S3328 continues to localize properly onto mitotic chromosomes during embryogenesis (arrow). Bars, ∼1 μm.

MEI-S332 has homotypic interactions and is in a multimeric complex

In vivo studies in S. cerevisiae with dimerized LacI–GFP fusion proteins suggested that protein–protein interactions may be sufficient to mediate sister-chromatid cohesion (Straight et al. 1996). Thus we determined whether MEI-S332 was capable of interacting with itself, a potential mechanism by which MEI-S332 could provide cohesion activity. We used two approaches to address this possibility: (1) The yeast two-hybrid system to test whether MEI-S332 is capable of binding to itself; and (2) immunoprecipitation to determine whether a complex containing more than one MEI-S332 protein subunit exists in vivo.

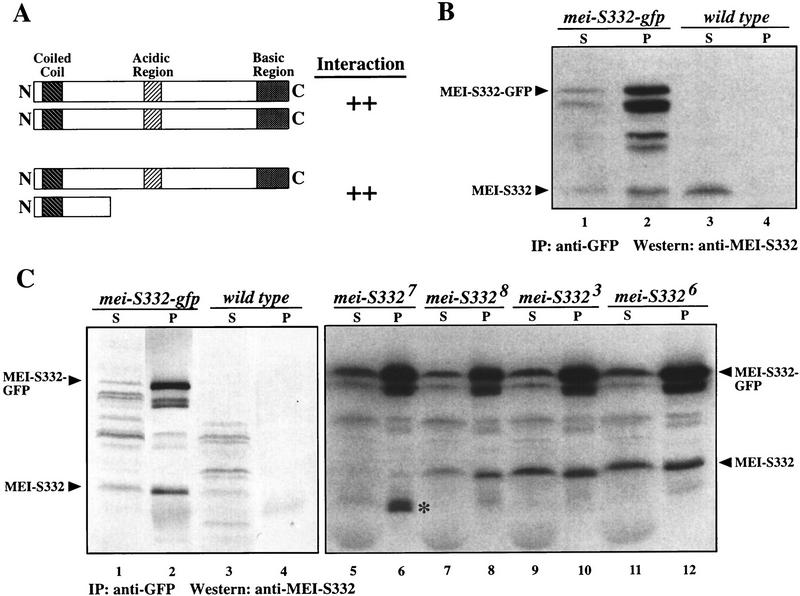

To determine whether MEI-S332 would bind itself in the yeast cell, we employed the LexA-based interaction system (Gyuris et al. 1993). Full-length MEI-S332 fused to an activation domain interacted strongly with full-length MEI-S332 fused to the LexA DNA-binding domain, resulting in high levels of expression from two reporter genes (Fig. 8A). A fusion containing only the amino-terminal third of MEI-S332 and the DNA-binding domain exhibited comparable levels of interaction with the full-length MEI-S332 fused to activation domain, showing that the carboxy-terminal two-thirds of MEI-S332 was not required for homotypic interaction in the yeast cell. A fusion containing only the carboxy-terminal two thirds of MEI-S332 and the DNA-binding domain activated on its own and hence could not be tested.

Figure 8.

MEI-S332 is capable of homotypic interactions and exists in a multimeric complex in vivo. (A) In a yeast two-hybrid assay, MEI-S332 was found to interact with itself. The amino-terminal third of MEI-S332, consisting of the predicted coiled-coil domain, was sufficient to mediate this interaction. (B) Endogenous MEI-S332 coimmunoprecipitates with MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein from 2- to 6-hr embryos. By use of anti-GFP antibodies, the MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein was precipitated from embryos of flies carrying the mei-S332–gfp transgene, and the immunocomplex was analyzed by immunoblotting with guinea pig anti-MEI-S332 antibodies. In addition to MEI-S332–GFP, a band corresponding to the endogenous MEI-S332 is also present in the immunoprecipitate from mei-S332–gfp extracts. This band is absent from wild-type immunoprecipitates lacking the MEI-S332–GFP fusion. (S) Supernatant fractions from the immunoprecipitation; (P) pellets from the immunoprecipitation. The amounts of proteins seen in S represent only ∼ of the total immunoprecipitation supernatant, whereas all of the pellet was loaded. Other bands in S and P from mei-S332–gfp extracts are likely to be degradation products of the MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein. (C) Endogenous MEI-S332 also coimmunoprecipitates with MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein from mature metaphase I-arrested oocytes. Probed with anti-MEI-S332 antibodies, the immunoblot of the immunoprecipitates demonstrates that the band corresponding to MEI-S332 is the endogenous MEI-S332 protein rather than a degradation product of MEI-S332–GFP. (The band is absent from the mei-S3327 immunoprecipitate). This complex is not disrupted by mutations in the coiled-coil domain or in the basic region, and consistent with the yeast two-hybrid result, the carboxy-terminal portion of MEI-S332 is not necessary for the formation of this multimeric MEI-S332 complex. Four mutant forms of MEI-S332 coimmunoprecipitate with MEI-S332–GFP. MEI-S3323, MEI-S3326, and MEI-S3328 have the same mobility as the wild-type protein (arrow), whereas the truncated MEI-S3327 protein migrates faster (*). Again, the endogenous MEI-S332 protein is absent in extracts from flies lacking the mei-S332–gfp transgene.

of the total immunoprecipitation supernatant, whereas all of the pellet was loaded. Other bands in S and P from mei-S332–gfp extracts are likely to be degradation products of the MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein. (C) Endogenous MEI-S332 also coimmunoprecipitates with MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein from mature metaphase I-arrested oocytes. Probed with anti-MEI-S332 antibodies, the immunoblot of the immunoprecipitates demonstrates that the band corresponding to MEI-S332 is the endogenous MEI-S332 protein rather than a degradation product of MEI-S332–GFP. (The band is absent from the mei-S3327 immunoprecipitate). This complex is not disrupted by mutations in the coiled-coil domain or in the basic region, and consistent with the yeast two-hybrid result, the carboxy-terminal portion of MEI-S332 is not necessary for the formation of this multimeric MEI-S332 complex. Four mutant forms of MEI-S332 coimmunoprecipitate with MEI-S332–GFP. MEI-S3323, MEI-S3326, and MEI-S3328 have the same mobility as the wild-type protein (arrow), whereas the truncated MEI-S3327 protein migrates faster (*). Again, the endogenous MEI-S332 protein is absent in extracts from flies lacking the mei-S332–gfp transgene.

To examine the association between MEI-S332 subunits in vivo, we immunoprecipitated a MEI-S332–GFP fusion protein and tested whether the endogenous MEI-S332 was present in the immunocomplex by immunoblotting the immunoprecipitates. Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies pulled down not only MEI-S332–GFP but also the endogenous MEI-S332 present in mei-S332–gfp transgenic embryos (Fig. 8B). As a negative control, no MEI-S332–GFP was present in the parallel immunoprecipitate from wild-type nontransgenic embryo extracts; MEI-S332 was also absent from this immunoprecipitate. Similar results were seen with oocytes (Fig. 8C, cf. lanes 3 and 4 to lanes 1 and 2). We confirmed that the indicated band (Fig. 8B) was the endogenous MEI-S332 by performing a parallel immunoprecipitation using oocyte extracts from homozygous mei-S3327 mutant females that expressed MEI-S332–GFP. Although the fusion protein was detected in the immunocomplex, the band corresponding to the endogenous wild-type MEI-S332 protein was absent from the complex (Fig. 8C, lane 6). Instead, a faster migrating band corresponding to the endogenous truncated MEI-S3327 protein was seen on the blot. Therefore, in embryos and oocytes, MEI-S332 is in a multimeric complex with more than one subunit of MEI-S332.

Combining the immunoprecipitation results with the results from yeast two-hybrid, we postulated that MEI-S332 interaction with itself was mediated by the predicted coiled-coil domain at the amino terminus. One prediction of this model is that the mei-S3328 mutation would disrupt MEI-S332 self-interaction. However, immunoprecipitation of mei-S3328 mutant, mei-S332–gfp transgenic oocyte extracts with anti-GFP antibodies showed that MEI-S3328 was still in the complex with MEI-S332–GFP (Fig. 8C, lane 8). Nevertheless, this result does not exclude the idea that MEI-S332 self-interaction is mediated through the coiled-coil domain, and we present several possibilities for this in the Discussion.

Preliminary results from gel-filtration and glycerol-gradient experiments indicated that MEI-S332 with a predicted molecular mass of 44.4 kD is present in two populations in embryos (data not shown). Most of the MEI-S332 protein is in a large complex of 200–1000 kD, indicating that MEI-S332 is in a multimeric complex. The less abundant form is 45–200 kD, suggesting a dimer of MEI-S332. The Multicoil program (Wolf et al. 1997) predicts that the coiled coil of MEI-S332 has a higher probability of forming a dimer than a trimer.

Intragenic complementation between the two MEI-S332 domains

Given that MEI-S332 can multimerize, it was possible that mutations disrupting the coiled-coil domain might complement mutations in the basic region, and vice versa. We tested this hypothesis by measuring the frequencies of meiotic chromosome nondisjunction and loss in female and male meioses in mei-S3326/mei-S3328. Strikingly, we observed complementation between the two alleles, mei-S3326 and mei-S3328 (Table 3). In males, mei-S3328 chromosome segregation was improved by the presence of mei-S3326 mutation. Similarly, mei-S3326 was improved by mei-S3328 in females. These results are due to intragenic complementation rather than the activity of the mei-S3326 gene in males or the mei-S3328 gene in females. mei-S3328/Df females had 22.3% nondisjunction, and mei-S3326/Df males had 12.0% nondisjunction (Kerrebrock et al. 1992; data not shown). Thus it appears that the MEI-S3328 mutant protein was able to tether the MEI-S3326 mutant protein, which is itself unable to localize to chromosomes, to the meiotic chromosomes in both males and females. Once on the chromosomes, the wild-type coiled-coil domain of MEI-S3326 may have compensated for the mutant coil in MEI-S3328. This genetic complementation strongly suggests that MEI-S332 is in a complex with itself in vivo, not only in females as seen with immunoprecipitations in oocyte extracts, but also in males.

Table 3.

Genetic complementation between two mei-S332 alleles

| Male tests | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genotype

|

Percent regular sperma

|

Percent exceptional sperma

|

Total progeny

|

Total percent mis-segregation

|

||||

| X | Y(Y) | O | XY(Y) | XX | XXY(Y) | |||

|

55.0 (991) | 43.9 (792) | 0.4 (8) | 0.2 (4) | 0.4 (8) | 0.0 (0) | 1803 | 1.1 |

|

50.2 (915) | 46.8 (854) | 1.8 (33) | 0.1 (2) | 1.1 (20) | 0.0 (0) | 1824 | 3.0 |

|

49.3 (240) | 47.4 (231) | 1.8 (9) | 0.2 (1) | 1.2 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 487 | 3.3 |

|

47.0 (239) | 33.9 (172) | 12.4 (63) | 1.2 (6) | 5.5 (28) | 0.0 (0) | 508 | 19.1 |

| Female tests | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genotype

|

Percent regular ovaa

|

Percent exceptional ovaa

|

Total progeny

|

Adjusted totalb

|

Total percent mis-segregation

|

|

| X | O | XX | ||||

|

90.8 (3686) | 4.1 (84) | 5.1 (103) | 3873 | 4060 | 9.2 |

|

92.4 (3333) | 3.5 (64) | 4.0 (73) | 3470 | 3607 | 7.6 |

|

62.3 (878) | 21.6 (152) | 16.2 (114) | 1144 | 1410 | 37.7 |

|

92.6 (1336) | 3.7 (27) | 3.6 (26) | 1389 | 1442 | 7.4 |

Number in parentheses indicate the numbers of progeny counted.

The total progeny is adjusted to correct for the recovery of only half of the total number of exceptional progeny.

Discussion

We found that the MEI-S332 centromere cohesion protein first assembles onto the chromosomes during prometaphase, and its chromosomal localization does not require intact microtubules. There are two functional domains of MEI-S332 that can act in trans to complement each other. The carboxy-terminal basic region of MEI-S332 is essential for chromosomal localization. Although the amino-terminal coiled-coil domain may not be necessary for localization, it may be involved in mediating protein–protein interactions with a yet-unidentified male-specific factor. Furthermore, MEI-S332 is capable of self-interaction, and this may facilitate its function in sister-chromatid cohesion.

MEI-S332 maintains sister-chromatid cohesion

To ensure proper chromosome segregation, the physical association between the duplicated sister chromatids appears to be established during or immediately after DNA replication, and it must be maintained until sister chromatids separate at the onset of anaphase. The timing of association and dissociation of the Xenopus cohesin complex raised the possibility of additional cohesion proteins to maintain cohesion in mitosis (Losada et al. 1998). It is intriguing that MEI-S332, shown to be required for sister-chromatid cohesion, does not assemble onto the chromosomes until prometaphase. Our interpretation is that MEI-S332 acts to maintain cohesion specifically at the centromere.

Why would a cell require multiple, different complexes for sister-chromatid cohesion? Losada et al. (1998) speculated that upon entry into mitosis, the cohesin complex must be cleared from the chromosomes to relieve steric hindrance that could otherwise prevent the condensin-mediated chromosome condensation. Consequently, the cohesin complex is dissociated from the chromosomes early, prior to the onset of sister-chromatid separation. If the condensins do not contribute to sister-chromatid cohesion activity, a possibility raised by the yeast mutants (Saka et al. 1994; Strunnikov et al. 1995), we postulate that additional cohesion proteins are required in mitosis. This would be particularly true at the centromeres. When kinetochores engage in microtubule attachment, additional centromere cohesion is likely to be needed to counteract the poleward pulling forces exerted on the kinetochores. On the basis of its spatial and temporal pattern of chromosomal localization, MEI-S332 may be a component of the maintenance complex, counteracting the poleward spindle forces by maintaining sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromeres. Consistent with this model, we found that MEI-S332 assembly onto the chromosomes is not dependent on microtubule attachment to the kinetochores. To maintain sister-chromatid cohesion against the poleward pulling forces, MEI-S332 would have to localize to the centromeres before the kinetochores capture microtubules.

A defined period of time when MEI-S332 has accessibility to chromosomes

The observation that more MEI-S332 localizes onto the chromosomes when nuclei are arrested in prometaphase suggests that there is a defined period of time, with both an onset and an end, when MEI-S332 can localize to the chromosomes. The fact that lengthening prometaphase allowed a mutant MEI-S332 protein with a crippled basic region to localize to chromosomes supports the model that there is a defined period of time when MEI-S332 has accessibility to the chromosomes. Whereas these results demonstrate an onset for when MEI-S332 is capable of assembling on the centromere, our failure to observe localization of MEI-S3326 mutant protein onto the chromosomes of mature oocytes suggests an endpoint beyond which MEI-S332 cannot localize. This endpoint would be marked by microtubule binding and spindle assembly. Mature oocytes are arrested indefinitely in metaphase I until the egg is activated (Theurkauf and Hawley 1992). Although the metaphase I arrest in mature oocytes should provide sufficient time for MEI-S332 mutant proteins with a crippled basic region to localize, we never observed MEI-S332 proteins with mutations in the basic regions on the karyosome. The distinction between our failure to observe MEI-S3326 localized in oocytes and its localization in colchicine-treated embryos is that the kinetochores are already attached to microtubules during metaphase I. We propose that microtubule attachment blocks the ability of MEI-S332 to localize. Thus, if MEI-S332 fails to localize in the preceding short prometaphase stage, it will not localize in mature oocytes regardless of how long the metaphase-I arrest lasts.

Functional domains within MEI-S332

Mutations in mei-S332 highlight two domains of the protein, a predicted coiled-coil domain at the amino terminus and a basic region at the carboxyl terminus. We found that these two domains have distinct functions. The basic region is essential for MEI-S332 chromosomal localization, whereas mutations in the coiled-coil domain do not have any effect on localization. The results from the intragenic complementation tests between mutations in the two domains provide compelling evidence that these two domains play essential but different functions. The basic region of MEI-S332 may bind to DNA directly, perhaps by recognizing specific DNA sequences in the centromeric heterochromatin. Alternatively, the basic region could be critical for protein–protein interactions between MEI-S332 and other DNA-binding factors.

The yeast two-hybrid and immunoprecipitation results demonstrate that MEI-S332 is capable of interacting with itself. The self-interaction of MEI-S332 could be mediated through the coiled-coil domain, even though mei-S3328, a mutation in the hydrophobic side of the coil, does not disrupt this self-interaction in the coimmunoprecipitation experiments. If more than two subunits of MEI-S332 are associated in a single complex and/or if there is another protein in the MEI-S332 complex, we would not expect to detect the effect of the coiled-coil mutation on self-interaction by coimmunoprecipitation. Because cohesion at the centromere may need to spread over a chromosomal domain and not be restricted to the kinetochore, it is reasonable that there may be more than two subunits of MEI-S332 in a complex and/or that they are associated with bridging proteins. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that on glycerol gradients and gel-filtration columns MEI-S332 migrates with a high molecular mass complex. Previous work with a LacI–GFP fusion protein in S. cerevisiae showed that sister-chromatid cohesion can be mediated via protein–protein interaction (Straight et al. 1996). It is attractive to think that the mechanism by which MEI-S332 functions to hold sister chromatids together is protein–protein interactions between MEI-S332 subunits on separate sister chromatids.

Mutations in the coiled-coil domain affect chromosome segregation more severely in males than in females. However, they do not have a detectable effect on MEI-S332 chromosomal localization. Therefore, we postulate that the coiled-coil domain interacts with some protein(s) necessary for male but not female meiosis. Because the basic region of MEI-S332 is required for chromosomal localization in both sexes, it is surprising that mutations in the basic region cause only limited chromosome mis-segregation in males. Perhaps the basic-region mutant proteins, MEI-S3322 and MEI-S3326, do localize to the chromosomes, although at a level lower than wild type and not detectable by the antibodies. Low levels of MEI-S332 on the chromosomes may be sufficient for proper sister-chromatid cohesion in males, but higher levels might be needed for females. Alternatively, MEI-S332 could be required on the male meiotic chromosomes only transiently but must remain associated with the female meiotic chromosomes from prometaphase until sister-chromatid separation at the onset of anaphase II. The reason could be that in addition to MEI-S332 there are other factors participating in sister-chromatid cohesion that are present in males but not in females.

All of the proteins necessary for sister-chromatid cohesion identified so far either do not localize to chromosomes (eg., Pds1p; Ciosk et al. 1998) or localize all along the length of the chromosomes (e.g., the cohesin complex; Michaelis et al. 1997). MEI-S332 is the only protein that localizes specifically to the centromeres. It functions to maintain sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromeres and appears to counteract the poleward pulling forces. It is attractive to think that in addition to being a structural component necessary for maintaining sister-chromatid cohesion, MEI-S332 also plays a regulatory role in sister-chromatid cohesion. Because the spindle assembly checkpoint components are observed at the centromeres along with the anaphase-promoting complex, MEI-S332 could interact with these proteins. Finally, MEI-S332 can be used as a bait for finding sex-specific factors necessary for proper chromosome segregation. Meiosis is different between males and females in D. melanogaster, and the identification and characterization of these sex-specific factors will help us understand the differences in the two sexes.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

To generate homozygous mei-S332 mutant flies, two different stocks of each allele were crossed to each other (Kerrebrock et al. 1992), and progeny of the genotype pr cn mei-S332 bw sp/cn mei-S332 px sp were selected. Alleles 9 and 10 are exceptions in that they were analyzed in trans to the Df(2R)X58-6 deficiency (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). The Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn/SM1 stock and Oregon-R were used as the wild-type control for Western blotting and MEI-S332 localization in embryos, oocytes, and spermatocytes. In addition, Oregon-R was also used as the negative control for immunoprecipitation experiments.

A y/y+Y; +/SM1 stock was used to isogenize the sex chromosomes in the mei-S332 mutant stocks. The isogenized mei-S332 and deficiency stocks were crossed to each other to generate mei-S332/Df(2R)X58-6 flies for the nondisjunction tests. C(1)RM, y2 su(wa)wa YSX · YL, In(1)EN y+ v f B, carrying attached XX and XY chromosomes, was used to measure sex chromosome nondisjunction and loss in meiosis.

In the studies of the MEI-S332 multimeric complex, females of the genotype y w P[w+mc 5.6KK mei-S332+::GFP=GrM]-7; +/SM1 and y w P[GrM]-7; +/+ were used to provide the MEI-S332–GFP-expressing oocytes and embryos for immunoprecipitation extracts. P[GrM]-7, an insertion of the fusion transgene mei-S332+::GFP on the X chromosome (Moore 1997), was crossed into both stocks of mei-S332 alleles 3, 6, 7, and 8 to generate mei-S332 mutants that express MEI-S332–GFP. This mei-S332–gfp transgene is functional in meiosis (Moore 1997).

Immunofluorescence in embryos, oocytes, and spermatocytes

Antibodies against a full-length MEI-S332 recombinant protein fused to GST were generated in guinea pigs. The cloning of the GST–MEI-S332 expression construct was described previously (Moore et al. 1998). The GST–MEI-S332 fusion protein was expressed in BL21(λDE3)pLysS cells by IPTG induction. The small fraction of soluble GST–MEI-S332 was purified with glutathione–agarose beads (Sigma Chemicals), combined with purified inclusion bodies containing the majority of the GST–MEI-S332 protein, and separated on standard 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels. The band corresponding to GST–MEI-S332 was excised, eluted, and injected into guinea pigs for antibody production (Covance, Denver, PA).

For immunofluorescence studies in mei-S332 mutant embryos, embryos were collected for 6 hr from females of the genotype pr cn mei-S332 bw sp/cn mei-S332 px sp as well as from Oregon-R control females, fixed essentially as described (Whitfield et al. 1990), and stained first with anti-MEI-S332 antibodies (1:5000 dilution), followed by Cy3-conjugated anti-guinea pig (1:150 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA), and then with anti-phospho H3 (1:500 dilution; D. Allis), followed by Cy2-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (1:100 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.).

Mature unactivated oocytes were prepared by use of protocols described by Theurkauf (1994) and Page and Orr-Weaver (1997) from fattened females of the genotype pr cn mei-S332 bw sp/cn mei-S332 px sp for alleles 2–8 and cn bw sp If mei-S332/Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn for alleles 9 and 10 as well as from Oregon-R and Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn/SM1 females. They were bound to MEI-S332 antibodies as described above for embryos, and stained with YOYO-1 iodide (Molecular Probes) at 1:1000 in PBS before dehydration in methanol and mounting in clearing solution.

To stain spermatocytes for MEI-S332 and tubulin, testes were dissected from newly eclosed males of the genotype described above and processed for immunostaining as described in Hime et al. (1996) with slight modifications. Slides were incubated with anti-MEI-S332 (1:10,000 dilution), followed by Cy3-conjugated anti-guinea pig, and then with rat monoclonal anti-tubulin (YL1/2 and YOL1/34 at 1:5 dilution; Sera-Lab Ltd., Sussex, UK), followed by Cy2-conjugated anti-rat antibodies (1:100 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). DNA was stained with DAPI at 1 μg/ml in PBS before the slides were mounted in glycerol containing 50 mg/ml n-propyl gallate.

Colchicine treatment of embryos

To arrest the mitotic cell cycles at prometaphase, Oregon-R embryos from a 2-hr or a 4-hr collection were dechorionated in 50% Clorox bleach, rinsed with Grace’s medium (GIBCO/BRL), permeabilized by Grace’s medium-saturated octane (Aldrich; Ashburner 1989), and incubated for 30 min. or 2 hr, respectively, in Grace’s medium with or without colchicine at 100 μg/ml. After colchicine treatment, embryos were immediately fixed and processed either for MEI-S332 and phosphorylated histone H3 immunostaining or for MEI-S332 and tubulin immunostaining followed by DAPI staining.

Microscopy

Two types of epifluorescence microscopy were used in our studies of MEI-S332 localization. In cases where tissues were triple-labeled, a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a 100× oil Plan Apo objective was employed to visualize the chromatin, spindles, and MEI-S332. Images were captured by a Photometrics CE200A cooled CCD video camera and subsequently processed with the CELLscan 2.1 system (Scanalytics) to create volume views from focal planes separated by 0.25 μm. When tissues were double-labeled, specimens were viewed with a confocal laser scanning head (MRC 600; Bio-Rad) that was equipped with a kryopton/argon laser and mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Oberkochen, Germany). A 40× oil Plan Neofluar objective was used. Adobe Photoshop 3.0 was used to process and merge the images; artificial colors were used.

PCR and sequencing of mei-S332 alleles

Genomic DNA from female flies of genotypes cn bw sp If mei-S3329/Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn, cn bw sp If mei-S33210/Df (2R)X58-6 pr cn, pr cn mei-S3325 bw sp/Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn, or cn mei-S3325 px sp/Df(2R)X58-6 pr cn was prepared by use of the single-fly DNA preparation protocol described by Gloor and Engels (1992), amplified by PCR with primers flanking the mei-S332 ORF, and subjected to automated DNA sequencing (Research Genetics). Two independently amplified PCR products were sequenced for each mutation. In addition, both strands of DNA were sequenced.

Western blot analysis

Protein extracts were prepared and Western blotting was performed as described previously (Moore et al. 1998) with the exception that ovaries were dissected in IB buffer [55 mm NaOAc, 40 mm KOAc, 100 mm sucrose, 10 mm glucose, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 100 mm HEPES (pH 7.4)], and anti-full-length MEI-S332 antibodies were used. Blots were first incubated with both guinea pig anti-MEI-S332 whole serum at 1:20,000 and rabbit anti-CDC2 antibodies (Edgar et al. 1994) at 1:5000 and then with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (Promega) diluted 1:2500 and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-guinea pig antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) at 1:5000. Visualization of bound HRP-conjugated antibodies was done first with the ECL chemiluminescent detection (Amersham), followed by that of bound alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies with CDP-Star as the chemiluminescent substrate (Tropix, Bedford, MA).

For mei-S332 alleles 2–8, ovary extracts were prepared from homozygous mutant females, and hence their relative MEI-S332 levels could be compared to that in the wild-type Oregon-R ovary extract. For mei-S332 alleles 9 and 10, the extracts were made from mei-S332/Df females, and thus, their relative MEI-S332 levels should be compared to that in Df/+ ovary extract. CDC2 protein levels were used as the loading controls.

Nondisjunction tests

Genetic assays used to measure the frequencies of sex chromosome nondisjunction and loss in both female and male meiosis were performed as described previously (Kerrebrock et al. 1992). Isogenized mei-S332/Df(2R)X58-6 virgin females or males were crossed to attached XY males or attached XX virgin females, respectively (see Fly Strains). The parents of the crosses were removed at day 7, and progeny were scored on days 13 and 18. Crosses with mei-S332/SM1 and Df(2R)X58-6/SM1 were included in the tests as controls. All crosses were kept at 25°C during the testing period.

Yeast two-hybrid and immunoprecipitation experiments

The full-length MEI-S332 coding sequence was cloned into the prey and bait vectors of Gyuris et al. (1993) by inserting a BamHI–DraI fragment of the mei-S332 cDNA. In addition, a BglII fragment that contains the amino-terminal third of the protein was cloned into the bait vector. Both the lacZ and leu2 reporter genes were used to test interaction as described (Golemis et al. 1997).

For immunoprecipitation experiments, embryos and mature unactivated oocytes were homogenized in IP buffer [150 mm or 500 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris (pH 8), 2.5 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 0.2% NaN3, 0.3 mm Na3VO4, 0.1 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml chymostatin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml soybean tripsin inhibitor). Then, NP-40 was added to the extracts to a final concentration of 1% before extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 4°C for 5 min. Extracts were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (Clontech) were added to the IP extracts and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C before binding to protein A–sepharose 6MB beads for 1 hr. Beads were washed 10 times at 4°C with NP-40 buffer [150 mm or 500 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris (pH 8), 2.5 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 0.2% NaN3, 0.3 mm Na3VO4, and 1% NP-40]. Finally, 2× SDS sample buffer was added to the beads, and the samples were heated at 95°C for 5 min and centrifuged for 5 min. The immunocomplexes were separated on SDS–polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by immunoblotting with guinea pig anti-MEI-S332 antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Allis for providing the anti-phospho H3 antibodies, D. Dawson for suggesting the intragenic complementation experiments, and D. Burney and R. Austin for their help with gel filtration and glycerol gradients. We thank K. Kaplan, J. Lee, K. Lemon, D. Lin, and F. Solomon for helpful comments on the manuscript. T.T.-L.T. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation (NSF), S.E.B. was a postdoctoral fellow of the Damon Runyon–Walter Winchell Cancer Fund, and this research was supported by grant MCB-9604135 from the NSF.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL weaver@wi.mit.edu; FAX (617) 258-9872.

References

- Ashburner M. Drosophila: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel SE, Orr-Weaver TL. Holding chromatids together to ensure they go their separate ways. BioEssays. 1996;18:293–300. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel SE, Wyman DW, Orr-Weaver TL. Mutational analysis of the Drosophila sister-chromatid cohesion protein ORD and its role in the maintenance of centromeric cohesion. Genetics. 1997;146:1319–1331. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenci G, Bonaccorsi S, Pisano C, Verni F, Gatti M. Chromatin and microtubule organization during premeiotic, meiotic, and early postmeiotic stages of Drosophila melanogaster spermatogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:3521–3534. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, O’Farrell PH. Genetic control of cell division patterns in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1989;57:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, Sprenger F, Duronio RJ, Leopold P, O’Farrell PH. Distinct molecular mechanisms regulate cell cycle timing at successive stages of Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:440–452. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE, Odell GM, Edgar BA. Mitosis and morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo: Point and counterpoint. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 149–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gloor G, Engels W. Single-fly DNA preps for PCR. Dros Inf Serv. 1992;71:148–149. [Google Scholar]

- Golemis EA, Serebriiskii I, Gyuris J, Brent R. Interaction trap/two-hybrid system of identify interacting proteins. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1997. pp. 20.1.1–20.1.35. [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V, Hogan E, Koshland D. Chromosome condensation and sister chromatid pairing in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:517–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A. A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1997;91:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett-Jones DP, Allis CD. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hime GR, Brill JA, Fuller MT. Assembly of ring canals in the male germ line from structural components of the contractile ring. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2779–2788. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Kobayashi R, Hirano M. Condensins, chromosome condensation protein complexes containing XCAP-C, XCAP-E and a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila barren protein. Cell. 1997;89:511–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Mitchison TJ. A heterodimeric coiled-coil protein required for mitotic chromosome condensation in vitro. Cell. 1994;79:449–458. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebrock AW, Miyazaki WY, Birnby D, Orr-Weaver TL. The Drosophila mei-S332 gene promotes sister-chromatid cohesion in meiosis following kinetochore differentiation. Genetics. 1992;130:827–841. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrebrock AW, Moore DP, Wu JS, Orr-Weaver TL. MEI-S332, a Drosophila protein required for sister-chromatid cohesion, can localize to meiotic centromere regions. Cell. 1995;83:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland D, Strunnikov A. Mitotic chromosome condensation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:305–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T. Identification of Xenopus SMC protein complexes required for sister chromatid cohesion. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1986–1997. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cohesins: Chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell. 1997;91:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki WY, Orr-Weaver TL. Sister-chromatid cohesion in mitosis and meiosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:167–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DP. ‘The mechanisms of chromosome segregation.’ Ph.D., thesis. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moore DP, Page AW, Tang TT-L, Kerrebrock AW, Orr-Weaver TL. The cohesion protein MEI-S332 localizes to condensed meiotic and mitotic centromeres until sister chromatids separate. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1003–1012. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A, Orr-Weaver T. Activation of the meiotic divisions in Drosophila oocytes. Dev Biol. 1997;183:195–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka Y, Sutani T, Yamashita Y, Saitoh S, Takeuchi M, Nakaseko Y, Yanagida M. Fission yeast cut3 and cut14, members of a ubiquitous protein family, are required for chromosome condensation and segregation in mitosis. EMBO J. 1994;13:4938–4952. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Belmont AS, Robinett CC, Murray AW. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister-chromatid cohesion. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunnikov AV, Hogan E, Koshland D. SMC2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene essential for chromosome segregation and condensation, defines a subgroup within the SMC family. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:587–599. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurkauf WE. Immunofluorescence analysis of the cytoskeleton during oogenesis and early embryogenesis. In: Goldstein LSB, Fyrberg EA, editors. Methods in cell biology. Vol. 44. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 489–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurkauf WE, Hawley RS. Meiotic spindle assembly in Drosophila females: Behavior of nonexchange chromosomes and the effects of mutations in the nod kinesin-like protein. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1167–1180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be established during DNA replication. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield WG, Gonzalez C, Maldonado-Codina G, Glover DM. The A- and B-type cyclins of Drosophila are accumulated and destroyed in temporally distinct events that define separable phases of the G2-M transition. EMBO J. 1990;9:2563–2572. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf E, Kim PS, Berger B. MultiCoil: A program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1179–1189. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]