Introduction

In 2004, Samuels et al. reported the results of the analysis of the sequences of all known lipid kinase genes in 35 colorectal cancers. PIK3CA, which encodes the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3Kα, was the only gene that showed somatic (i.e., tumor-specific) mutations [1]. Extension of this analysis to PIK3CA in 199 additional colorectal cancers revealed mutations in 32 % of the tumors (74 out of 199 tumors). In contrast, in 76 premalignant colorectal tumors only two mutations were found; both these tumors were very advanced tubulovillous adenomas. These observations were interpreted as indicating that PIK3CA mutations generally arise late in tumorigenesis, just before or coincident with invasion. In the same study, mutations PIK3CA mutations were also identified in several other tumor types, including those of the breast, brain, stomach, and lung. Subsequent studies have identified similar mutations in these and many other tumor types [2, 3]. Over 1500 such mutations are now recorded in a principle cancer mutation database[4].

The PIK3CA gene codes for p110α, the major catalytic subunit of PI3Kα. This subunit is composed of five domains: an adaptor-binding domain (ABD), a Ras-binding domain (RBD), a C2 domain, a helical domain, and a kinase domain [5–8]. The complete enzyme also contains one of several regulatory subunits of similar size and function. The regulatory subunits, such as p85α, also contain five domains: an SH3 domain, a GAP domain, an N-terminal SH2 (nSH2) domain, an inter-SH2 domain (iSH2), and a C-terminal SH2 domain (cSH2) [9, 10]. The iSH2 domain is responsible, in part, for binding the catalytic domain, while the nSH2 and cSH2 domains mediate the interactions between PI3Kα and the tyrosine kinase receptors that activate it.

Of the five p110α domains, mutations were initially found in the Adaptor Binding Domain (ABD), C2, helical domain, and the kinase domain. No mutations were found in the Ras binding domain. A large percentage of mutations (~75%) occurred in two clusters—one in the helical domain and the other in the kinase domain [1]. Mutations have since been identified in 140 of the 1068 residues of PIK3CA. While some of these mutations are rare, others are commonly observed. The residues with the highest number of observed mutations, so-called “hotspots” are His1047 in the kinase domain (470 occurrences) and Glu545, Glu542 and Gln546 (362, 193, and 51 reported occurrences, respectively).

Samuels et al. also showed that the H1047R mutation resulted in a small but significant increase in enzymatic activity with respect to the wild type [1]. Subsequently, it was determined that two additional high frequency mutations, E542K and E545K, also increased enzymatic activity [11]. The increase in activity produced by the mutations was similar in magnitude to the increase that is observed when PI3Kα is activated by its physiological effectors, including phosphorylated tyrosine kinase receptors and their substrates [12]. These data were interpreted as indicating that the observed mutations of p110α result in a constitutively activated enzyme, which in turn regulates cellular pathways that contribute to several aspects of tumor growth. These considerations made PI3Kα an ideal target for the development of chemotherapeutic agents.

PI3Kα is only one of several PI3K enzymes that are central to numerous aspects of metabolism and cell growth. Because of the potential toxicity associated with such pleiotropic enzymes, chemotherapeutic agents that target PI3Kα must be at least isoform-specific, preferentially inhibiting the PI3Kα isoform over the others. The ideal agent would of course be one that inhibited mutant PI3Kα but not normal (wild type or wt) forms of the enzyme. Structural information is crucial for this type of development.

The structure of a major portion of the complete PI3Kα, determined by x-ray diffraction, provided the first look at the overall subunit organization of the enzyme as well as the positions of mutations within the 3-dimensional structure [7]. This structure contains many of the portions of the enzyme most important for the regulation of enzymatic activity and for understanding the effects of common mutations: the complete p110α and two domains of the regulatory subunit p85, viz., nSH2 and iSH2. Of the four regions of p85, iSH2 is absolutely required for binding to p110 and nSH2 is the domain most directly involved in PI3K regulation [13]. The iSH2 domain is a long coiled-coil that protects the large subunit from degradation by cellular proteases [14]. The nSH2 domain has an inhibitory effect on the kinase activity, but this inhibition is relieved when the domain binds to a phosphorylated tyrosine from an activated upstream protein [12]. In this regard, activation of PI3Kα is, in reality, removal of the inhibition by nSH2.

In addition, the same portion of the oncogenic H1047R mutant of PI3Ka was determined as the free enzyme and in complex with the covalent inhibitor wortmannin [15].

Description of the Structure

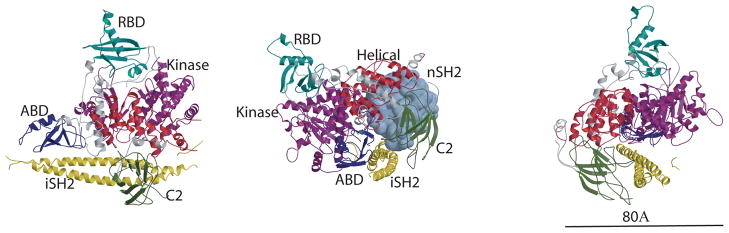

The p110α/niSH2 complex [7] is a large sail-boat shaped molecule with a narrow cross section (~80 Å, Fig. 1) [7]. The base is approximately 100 Å and its height 100 Å. The p110 portion forms the “sail” while the iSH2 of p85 constitutes the “hull” (Fig. 1a). Four of the p110 domains are arranged roughly along the top edge of p85, with the RBD at the top of the molecule. The base of the p110 subunit has the ABD at one end and the kinase domain at the other but permits a direct interaction between these two domains. The helical and C2 domain are closer to the center of the structure, at one side of the kinase domain along the narrow thickness of the subunit.

Figure 1.

Structure of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer. (A) Ribbon diagram of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer. For p110α, ABD is colored navy blue, RBD is turquoise, C2 is green, helical is red and kinase is purple. p85α iSH2 is yellow; all linkers are colored gray. (B) View of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer highlighting the iSH2-ABD and iSH2-C2 contacts. The nSH2 domain is modeled in a light blue surface. In this orientation of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer, the kinase, C2 and iSH2 domains are in contact with the membrane. (C) View of p110α/niSH2 at 90° from (A) that highlights its shape and dimensions.

The ABD (residues 1–108) and the RBD (residues 191–291) domains interact with the kinase domain over a large surface area. They both fold with α/β topologies and are connected to each other by an 81 residue linker (109–190) that contains two helices.

A short helix and a long coil (residues 292–329) connects the RBD to the C2 domain (residues 330 to 480), which folds as a β-sandwich composed of two four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets. C2 interacts not only with the helical and kinase p110 domains but also with the iSH2 domain of p85: H-bonds between Asp560 and Asn564 of iSH2 to Asn345 of C2 form the major interaction sites. The topology of the C2 domain of the p110 domains in class I PI3K enzymes appears to be highly conserved despite the fact that this domain has lower sequence homology than the other four domains (27% identity between α and γ). The differences between the C2 domains of p110α and p110γ are concentrated in the loops connecting the β-strands and includes insertions/deletions: the loop spanning residues 406 to 424, for example, is ten residues shorter in p110α than in p110γ (Fig. 2). Differences in conformation between the loops of the two isoforms may be a consequence of the interaction of the C2 domain of p110α with the iSH2 domain of the regulatory subunit p85 (p85 is not the regulatory subunit of p110γ). Importantly, the conformation that the loops adopt in p110γ makes it impossible for the iSH2 coiled-coil to fit in a position equivalent to that of the p110α/niSH2 complex.

Figure 2.

Structural alignment and overlap of human p110α/niSH2 heterodimer (PDB id 2RD0) and wild boar p110γ (PDB id 1E8X)in relationship to the iSH2 domain of p110α. (A) Ribbon diagram of the p110α/niSH2 C2 (green) and p110γ C2 (lavender) domains showing the differences in loops and CRB2. (B) Structural overlap of the kinase domains of structure 2RD0 (purple) and 1E8X (green). Helices that show the largest differences as well as the ATP are shown. Observed C-terminal residues in both structures are also shown (1050 and 1092)

The helical domain is connected through a linker (residues 481 to 524) to the C2 domain and through another linker (residues 525 to 696) to the kinase domain (Fig. 1). The kinase domain (residues 696 to 1068) folds as an α/β structure composed of two subdomains separated by a cleft that harbors the catalytic site of the enzyme, in an arrangement reminiscent of other kinases. This similarity allows assignment of the catalytic and the activation loops of p110α to residues 912 to 920 and 933 to 957. The structure of this domain is conserved among Class I PI3Ks (rmsd between p110α and p110γ for 288 Cα atoms is 1.8 Å), especially for residues surrounding the binding pocket. The largest differences occur in the the helices spanning residues 856 to 865, a region that lines the ATP binding site, as well as in residues 1032 to 1048 (rmsd 3.2 Å), a region that contains two positions that are mutated with high frequency in cancers, (Fig. 2b). The ATP binding site was identified by aligning the structure of the kinase domain of p110α with that of the same domain in the structure of the complex of p110γ with ATP. The high degree of similarity between the two structures in this region allowed an unambiguous localization of the ATP.

Association with the lipid membrane

Although PI3Ks are not integral membrane proteins, their substrate, PIP2 is mainly found as a plasma membrane component. To gain access to their substrates, PI3Ks must be recruited to the plasma membrane. The C2 domain within the p110 sequence is thought to provide a locus for the association of PI3Ks with membranes. In PI3Kα, iSH2 binds between the C2 domain and the rest of the p110 in such a way that if C2 and the kinase domain interact with the membrane, iSH2 must also interact (Fig. 3). In this arrangement, iSH2 would provide a large contact surface lined with positively charged residues lysines 447, 448, 480, 530, 532, 551, and 561, and arginines 461, 465, 472, 480, 523, 534, 543, and 544 (Fig. 3c). Residues 723 to 729 and 863 to 867 of the kinase domain, which includes positively charged residues Lys 723, Lys729, Lys 863, and Lys867 complete this surface. Arg349, Lys410, Arg412, Lys413, and Lys416 of the C2 domain of p110 may also interact with the membrane.

Figure 3.

Model of the association of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer with the lipid membrane. (A) Model of the lipid membrane with a ribbon diagram of the p110α/niSH2 structure. A black box highlights the loops that move in the mutant structure. (B) Model of the lipid membrane with a ribbon diagram of the p110α H1047R/niSH2. A black box highlights the loops that change conformation (residues 864–874 and 1050–1062). (C) Face of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer that interacts with the membrane; the iSH2 is shown as yellow ribbons. Positively charged residues, such as lysines and arginines, are shown in black as ball and stick representations.

Cancer-specific mutations

The cancer-associated mutations that have been identified in the ABD, C2, helical and kinase domains of p110α were believed to act through unrelated mechanisms [16, 17] but these hypotheses were difficult to interpret in the absence of structural information. The structure of the p110α/niSH2 suggest specific mechanisms through which these mutations increase kinase activity [7, 18, 19].

As the ABD domain was known to interact with p85, ABD mutations Arg38Cys, Arg38His and Arg88Gln were initially thought to disrupt the interaction between ABD and iSH2. However, the structure of the complex between ABD and iSH2 showed that these mutations are not located at the interface between the two domains [20]. In the structure of the p110α/niSH2 heterodimer, Arg38 and Arg88 are located at a contact surface between the ABD and the kinase domains, at hydrogen bonding distance (<3.2 Å) of Gln738, Asp743, and Asp746 of the N-terminal lobe of the kinase domain (Fig. 4a and 4b). Thus, mutations of Arg38 and Arg88 are likely to disrupt these interactions, resulting in a conformational change of the kinase domain that alters enzymatic activity.

Figure 4.

Somatic mutations of p110α identified in human cancers localize to domain interfaces. (A) Location of representative mutations within p110α and niSH2. Amino acids mutated in cancers are shown as CPK models and framed with a black box. (B) ABD Arg38 and Arg88 mutations at the interface of the ABD and kinase domains. (C) C2 Asn345 mutation at the interface with iSH2. The C378R mutation is also shown. (D) C2 E453N mutation at the interface of C2 with iSH2 on one side and modeled nSH2 on the other side. (E) Mutations in the helical domain (Glu542, Glu545, and Gln 546) are located at the interface with nSH2 (light blue surface). (F) Helical Gln661 mutation is located across from kinase domain residue His701, which also is independently mutated. (G) Kinase Met1043 and His1047 located near the C-terminal end of the protein, shown in relationship to the helical domain (red), the iSH2 domain (yellow) as observed in the p110α H1047R/niSH2 structure.

Before the determination of the structure of the p110α/niSH2 complex, the C2 domain was considered to be the main locus of interaction of PI3K with the membrane. Not surprisingly, mutations in the C2 domain were thought to change the affinity of p110α for the lipid membrane [19]. In the structure of the complex however, Asn345, which is mutated to Lys in some cancers, is within hydrogen bonding distance (2.8 Å and 3.0 Å) of Asn564 and Asp560 of iSH2, suggesting that mutation of Asn345 would disrupt the interaction of the C2 domain with iSH2, (Fig. 4a and 4c). This mutation may alter the regulatory effect of p85 on p110α rather than disrupt the interaction between p110α with the membrane. Another mutation identified in cancers, Glu453Gln, is also located at the interface between C2 and iSH2, Fig. 4d. A recently identified mutation (Cys378Arg) most likely increases the positive charge of the surface proposed to interact with the membrane, as it is contiguous with the surface of the iSH2 domain (Fig. 4c and 4d).

The two residues of the helical domain that are most frequently mutated in cancers are Glu542 and Glu545 (Fig. 4e). In the majority of cases, these two residues are mutated to Lys, causing a charge reversal. These residues as well as the less frequently mutated Gln546 are located on an exposed region of the helical domain (Fig. 4e). Biochemical studies suggested that they interact with Lys379 and Arg340 of the p85 nSH2 domain and that this interaction inhibited the activity of the catalytic subunit [20]. Though nSH2 was included in the wild type p110α/niSH2 protein complex, it was not highly ordered in the crystal. However, in the crystal structure of the same construct carrying the H1047R mutation, the nSH2 domain was clearly visible [15]. In this structure, the nSH2 is located close to the interface between the kinase and the helical domain, in a manner that allows it to interact with both domains as well with the C2 domain of p110α. Biochemical experiments showed that mutations at residues 542, 545, and 546 abrogate the inhibitory effect of nSH2 [20]. The structure suggests a mechanism through which the mutations may have this effect: they could modify the interaction of nSH2 with the helical and the kinase domains in a manner similar to that achieved by binding of the phosphotyrosine residue of physiological activators to nSH2. Other examples of somatic mutations at the interface between domains are provided by those at His701 of the kinase domain and Gln661 at the helical domain (Fig 4f).

His1047 in the kinase domain is another hot spot for somatic mutations in cancer and is associated with an unfavorable clinical prognosis breast cancers [21–23]. It is interesting that His1047 is mutated to Arg in the majority of cases, yet arginine is normally present at the homologous position in human p110γ (Fig. 4g). In the structure of the p110α/niSH2 p85 complex of the wild type enzyme, His 1047 is located within a helix of the C-terminal lobe of the kinase domain and is close to the C-terminal end of the activation loop, making a hydrogen bond with the main chain carbonyl of Leu956 within the activation loop. In the structure of the H1047R mutant with and without wortmannin [15], (Fig. 5), the orientation of the arginine side chain of residue 1047 is perpendicular to that of the histidine residue in the wild type. In this orientation, Arg 1047 occupies a crevice in the kinase domain and points toward the membrane (Fig. 4g). Additional effects of this mutation include ordering of the C-terminal residues of p110α 1050 to 1062, which were disordered in the wild type (Fig. 3a). The new orientation of this loop places some of its residues directly on the surface that was proposed to interact with the membrane (Fig. 3b). The conformation of another loop (residues 864–874) that also interacts with the membrane assumes different conformations in the wild type and the mutant (Fig. 3a, b). Taken together, these changes suggest that the gain of function that results from the H1047R is a result of stronger interaction of the mutant with the membrane that, in turn, provides increased accessibility to the PIP2 substrate. This mode of increasing enzymatic activity is compatible with the observation that binding to a cognate phosporylated peptide further increases the activity of this mutant [11]. Another less frequently observed mutation, Met1043IIe, is located on the same helix and may exert its effect through changes in the activation loop (Fig. 4g).

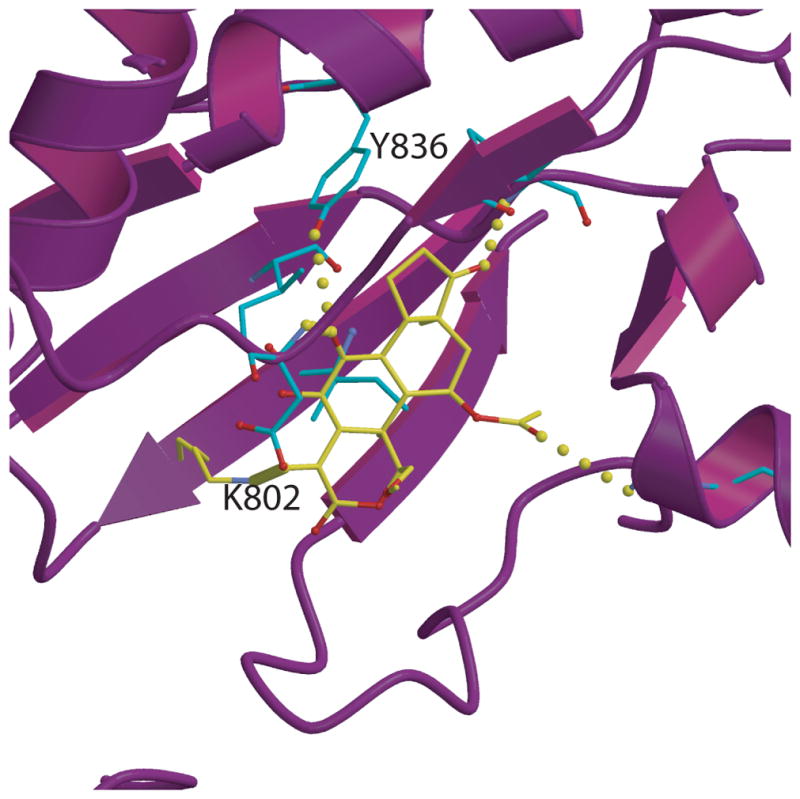

Figure 5.

Wortmannin bound to the p110α H1047R/niSH2. The kinase domain is shown as purple ribbons with the wortmaninn carbons in yellow. The covalent bond between K802 and wormannin is shown as a thicker line to distinguish it from other bonds. Residues at hydrogen bonding distance Q859, Y836, V851 are shown in turquoise.

In addition to mutations in p110α, mutations in p85α have been observed, particularly in brain tumors [2, 3]. Residues Asn564 and Asp560 of iSH2, which make H-bonds with Asn345, were found to be mutated. These iSH2 mutations probably affect PI3K activity by the same mechanism proposed above for the Asn345 mutations, i.e., by disrupting the interaction between the iSH2 and C2 domains.

Most other mutations in p85α have involved truncations or deletions starting at or near residue 571 (Fig. 6). In particular, a truncation mutant known as p65, that lacks all amino acids C-terminal to residue 571 leads to constitutively activated PI3Kα activity [24]. It is possible, that residues 581–593 constrain the location of the inhibitory nSH2 domain and that the deletion removes this constraint. Based on the crystal structure of p110/niSH2, however, an alternative possibility appears more likely: truncation at residue 571 might destabilize the iSH2 coiled-coil around residues 560 and 564 that make an important contact with Asn345 of the C2 domain (Fig. 6). Thus, the effect of this truncation may also be equivalent to that of the Asn345 mutation discussed above.

Figure 6.

Somatic mutations of p850α identified in human cancers. (A) Modeled structure of nSH2 domain shown as a surface in relation to C2, iSH2 and helical domains. Single mutations observed in the iSH2 are shown as stick and ball representations (Lys 459, Asp 464, Glu 560, Asn 564, Trp583); the indel mutation is shown in turquoise (DKRMNS560del) and p65 (deletion from 571) is shown in orange. (B) Location of mutations with respect to the indicated domains with p85α.

Another intriguing mutation identified in p85α is Gly376Arg. Residue 376 is within the nSH2 domain in a tightly packed volume at the interface between nSH2 and the C2 domain of p110α. It forms a close contact with Glu365 of C2 and substitution of the glycine at residue 376 with a bulky positively, charged arginine residue would disrupt this contact.

In sum, most of the p85α mutations described to date, whether they be subtle point mutations or large deletions, appear to disrupt the interaction between nSH2 and iSH2 and the C2 domain of p110α, thereby relieving inhibition of the kinase domain by nSH2.

Summary and Conclusions

PI3Kα is mutated in many cancers and biochemical analyses have shown that they often result constitutively activated enzymes. Some mutants, such as H1047R, can be further activated by tyrosine phosphorylated peptides derived from their physiological effectors. The increased PI3Kα activity of the mutants activate downstream processes that control cell growth, survival, apoptosis, differentiation, motility, migration, and adhesion. Structural information on PI3Kα has provided an initial look at possible mechanisms through which the oncogenic mutations may result in enzyme activation. Most commonly, mutations occur at the interfaces between p110α domains or between p110α and p85 domains, disrupting the negative regulatory influences that results from the interfacial contacts. Other mutations, such as H1047R, may affect the activity of PI3Kα by changing the interaction of the protein with the membrane.

References

- 1.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304(5670):554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons DW, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.TCGAR Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Catalogue of Somatic Cancer Mutations. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296(5573):1655–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD. Signaling by distinct classes of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253(1):239–54. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CH, et al. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318(5857):1744–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amzel LM, et al. Structural comparisons of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8:665–669. doi: 10.1038/nrc2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escobedo JA, et al. cDNA cloning of a novel 85 kd protein that has SH2 domains and regulates binding of PI3-kinase to the PDGF beta-receptor. Cell. 1991;65(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90409-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otsu M, et al. Characterization of two 85 kd proteins that associate with receptor tyrosine kinases, middle-T/pp60c-src complexes, and PI3-kinase. Cell. 1991;65(1):91–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90411-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson JD, et al. Effects of oncogenic p110alpha subunit mutations on the lipid kinase activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J. 2008;409(2):519–24. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, et al. Regulation of the p85/p110 phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase: stabilization and inhibition of the p110alpha catalytic subunit by the p85 regulatory subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(3):1379–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J, Wjasow C, Backer JM. Regulation of the p85/p110alpha phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Distinct roles for the n-terminal and c-terminal SH2 domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(46):30199–203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Z, et al. The iSH2 domain of PI 3-kinase is a rigid tether for p110 and not a conformational switch. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432(2):244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelker D, et al. A frequent kinase domain mutation that changes the interaction between PI3Ka and the membrane. PNAS. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Class I PI3K in oncogenic cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2008;27(41):5486–96. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110alpha of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2652–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CH, et al. Insights into the oncogenic effects of PIK3CA mutations from the structure of p110alpha/p85alpha. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1151–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogt PK, et al. Cancer-specific mutations in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(7):342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miled N, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317(5835):239–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai YL, et al. PIK3CA exon 20 mutation is independently associated with a poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(4):1064–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerma E, et al. Exon 20 PIK3CA mutations decreases survival in aggressive (HER-2 positive) breast carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2008;453(2):133–9. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalinsky K, et al. PIK3CA mutation associates with improved outcome in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5049–59. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimenez C, et al. Identification and characterization of a new oncogene derived from the regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. EMBO J. 1998;17(3):743–53. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]