Abstract

From 1975 to 1997, 649 cases of benign giant cell tumours of the bone were treated at the Istituto Rizzoli. Fourteen patients (2.1%) experienced lung metastases after a mean of 35.2 months. The time interval between the diagnosis and the appearance of the lung metastases ranged from 3 months to 11.9 years. Metastasectomy was performed in all patients. Histologically, the metastases were identical to the primary bone lesions. Two patients with unresectable multiple metastases received additional chemotherapy. After a follow-up of 70 months (range: 8.2 to 185 months), all patients are alive. Ten patients showed no evidence of disease, one of these after a second resection of metastases, and four patients presented stable disease with multiple lung metastases. Local recurrence of the bone lesion occurred in seven patients before or simultaneously to the metastases. In contrast to previous reports, we could not detect a predominance of the distal radius, but all of the patients had a stage III tumour according to the Enneking criteria of benign lesions. We conclude that even metastatic benign giant cell tumours have an excellent prognosis after adequate resection. No prognostic factors despite high-grade lesions were detectable.

Résumé

Entre 1975 et 1997, 649 cas de tumeurs à cellules géantes ont été traités à l’Institut Rizzoli. Quatorze patients (2.1%) ont présenté une métastase pulmonaire après une évolution moyenne de 35,2 mois. Le temps intermédiaire entre le diagnostic et l’apparition d’une métastase a varié de 3 mois à 11.9 ans. Chez tous les patients, la résection de la métastase a été réalisée, histologiquement, les métastases étaient identiques aux lésions primaires. Deux patients pour lesquels la résection de métastases multiples n’a pas été possible ont bénéficié d’une chimiothérapie. Après une moyenne de 70 mois (8.2 à 185 mois) tous les patients sont en vie. Dix patients ne montrent aucun problème particulier. Parmi les patients ayant bénéficié d’une seconde résection de métastase, quatre présentent un état stable malgré des métastases pulmonaires multiples. La récidive locale de la tumeur est survenue chez sept patients avant ou de façon concomitante à l’apparition des métastases. Contrairement à une étude précédente, nous n’avons pas remarqué de prédominance de lésions de l’extrémité inférieure du radius. Tous les patients avaient une tumeur de stade 3 selon les critères de Enneking. Nous pouvons conclure que, malgré une métastase, les tumeurs à cellules géantes bénignes peuvent avoir un excellent pronostic après une résection correcte. Nous n’avons pas mis en évidence de facteur de pronostic défavorable malgré le grade élevé des lésions.

Introduction

Since the first report of lung metastases following a benign giant cell tumour by Finch and Gleave in 1926 [6], despite a number of case reports, only a few large series have been reported [2, 17, 19, 21]. Benign giant cell tumours of the bone are well known to recur frequently (25–44.6%) depending on the primary resection margins [2] and the localisation of the tumour.

Attempts to correlate these findings with the histological grading, as well as with the prognostic value of risk factors such as the age, sex, anatomical site, presence or absence of pathological fractures, state of the disease, bony width involved and proximity to the joint, have failed [10]. Other authors have argued that the primary tumour site and local recurrences seem to favour the development of lung metastases [2, 19]. Patients who experienced at least one local recurrence were reported to be more likely to develop lung metastases than those who had no local recurrence. Patients with positive cells for Ki-67 in immunohistochemistry in stage III giant cell tumours seemed to have a higher prevalence of lung metastases [16].

The most effective treatment of the lung metastases is considered to be segmental resection of the lesions. In unresectable cases, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be alternative treatments. The mortality rate of metastasising giant cell tumours is reported to be between 0 and 25% [1, 17, 21].

The aim of this paper was to add the single-institution experience with 14 histologically proven lung metastases from a series of 649 patients with benign giant cell tumours of the bone.

Materials and methods

Since 1900, 936 cases of benign giant cell tumour of the bone have been treated at the Istituto Rizzoli, Bologna, Italy. Conventional X-ray examination of the chest or more recently CT scans of the lungs have been performed routinely in these patients since 1975. Therefore, 649 patients (305 males and 344 females) treated between 1 January 1975 and 1 July 1997 were included into this study. Of these, only patients who also had histologically verified diagnoses of lung metastases from benign giant cell tumours of the bone were included. Benign giant cell tumour was characterised by the absence of atypical nuclei and a high mitotic rate. Fourteen patients (2.1%) out of 649 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Clinical and radiological follow-up was obtained from the medical records for a mean of 70 months (range: 8.2 to 185 months) after the diagnosis of the lung metastasis. Definitive surgical treatment of the primary bone lesions was performed at the Orthopaedic Department of Rizzoli; all of the lung metastases were operated on by one of the co-authors. X-rays of the chest were available in 13 patients, and additional CT scans of the lungs could be analysed in nine patients. The data concerning the site, extension and number of the pulmonary lesions were completed by the medical reports of the thoracic surgeon. The patient data were analysed according to the age, sex, primary site of the bone lesion, surgical treatment, prior operations before admission to the authors institution, histological grading of the primary tumour and analysis of local recurrences before the diagnosis of pulmonary metastases. Blood group data were available for 13 patients. The demographic data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of 14 patients with lung metastases

| Patient | Sex | Age(years) | Localisation | Stage | First operation | Local recurrence | Local adjuvants | Pulmonary metastases | CHT | Follow-up after ME | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Months | Treatment | Months | Treatment | Months | |||||||

| 1 | F | 29.3 | Distal femur | 3+ | Tumour resection-endoprosthesis | 24.1 | Tumour resection- | 32.9 | ME | − | 8.2 AWD | |

| Endoprosthesis | ||||||||||||

| 2 | M | 27.4 | Prox. humerus | 3+ | Tumour resection-endoprosthesis | − | 11.3 | ME | − | 19 NED | ||

| 3 | F | 28.6 | Prox.tibia | 3 | Curretage, *bone cement | 3 | Excision of soft tissue nodules | − | ||||

| 4.6 | Tumour resection-endoprosthesis | 48.7 | ME | - | 17 NED | |||||||

| 4 | F | 29.6 | Distal humerus | 3 | Tumour resection-bone graft | − | 55.8 | WR | − | 172 NED | ||

| 5 | M | 25.5 | Prox.tibia | 3 | Curretage *bone graft | 24 | Tumour resection-bone cement | 27.4 | WR | − | 185 NED | |

| 6 | M | 21.0 | Distal femur | 3 | Tumour resection-bone graft | 18.1 | Excision of soft tissue nodules | 20.3 | WR | − | 137 NED | |

| 7 | M | 18.8 | Distal femur | 3 | Curretage, *bone graft | 5 | Curretage, bone graft | Phenole | ||||

| 27.6 | Curretage Bone cement | Phenole | 28.7 | WR | − | 150 NED | ||||||

| 8 | M | 33.7 | Prox.tibia | 3 | Curretage, *bone graft | 14 | Tumour resection, bone graft | |||||

| 44.6 | Excision of one distant soft tissue nodule | 143.3 | Incomplete ME | − | 29 AWD | |||||||

| 9 | M | 25.8 | Distal femur | 3 | Curretage, *bone graft | 5 | Excision of soft tissue nodules | |||||

| 8 | Curretage, bone cement * | Phenole | 14.2 | Biopsy | + | 90 AWD | ||||||

| 26 | Excision of soft tissue nodules | |||||||||||

| 10 | F | 37.9 | Distal femur | 3 | Marginal tumour resection-endoprosthesis | − | 30.4 | ME | − | 39 NED | ||

| 11 | M | 22.4 | Distal radius | 3 | Marginal tumour resection-endoprosthesis | 32.6 | Tumour resection, bone graft arthrodesis | 28.1 | WR | − | ||

| 80.9 | WR | 49 NED | ||||||||||

| 12 | F | 21.2 | Distal femur | 3 | Curretage, bone cement | 53.6 | Curretage, bone cement | Phenole | 36.3 | WR | − | 88 NED |

| 13 | F | 20.6 | Distal femur | 3 | Tumour resection-endoprosthesis | − | 0.3 | Biopsy | + | 49 AWD | ||

| 14 | M | 38.1 | Prox.fibula | 3 # | Fibular esection * | 5 | Tumour resection * | 14.6 | ME | − | ||

| 13 | Amputation | 26.4 | LOB | 21 NED | ||||||||

+St.p. pathological fracture

# Pulmonary metastases diagnosed on admission

*Therapy elsewhere

LOB: lobectomy

WR: wedge resection

ME: metastasectomy

CHT: chemotherapy

NED: no evidence of disease

AWD: alive with disease

Results

Six female and eight male patients with a mean age at diagnosis of 27.1 years (range: 18.8 to 38.1) experienced lung metastases after a mean of 35.2 months (range 0.3 to 143.3) of their primary treatment.

The primary tumour was predominantly located around the knee joint (71%): in seven patients at the distal femur (50%) and in three patients at the proximal tibia (21%). The localisation of the remaining four patients was the proximal humerus, the distal humerus, the distal radius and the proximal fibula.

Six patients had a surgical intervention of the primary tumour 3 months to 2 years before admission (five curettages and one resection of the fibula). Two of them had a history of two surgical interventions. In eight patients the initial therapy was performed at Rizzoli (seven resections and one curettage).

Therapy in the six patients who were admitted for local recurrence consisted of three resections, one amputation, one curettage and two excisions of soft tissue nodules. Radiologically, all patients had a stage III lesion according to Enneking. Two patients had a pathological fracture on admission.

Local recurrence occurred in three of the primarily treated patients at 18, 24 and 54 months, respectively, and in three patients after prior operations.

Pulmonary metastases were diagnosed at a mean of 35.2 months (0.3–143.3) after the first operation. In three patients, metastases were obvious at the first admission, in three patients pulmonary metastases were diagnosed after 3 years (31%) (Figs. 1, 2, 3), and in one patient after more than 11 years (143 months). Twelve patients had a mean of 4.6 pulmonary lesions (range: 1 to 9), and in two patients disseminated bilateral metastases were diagnosed. Ten patients had at least one local recurrence before pulmonary metastases occurred (71%), but four patients had no prior local recurrence.

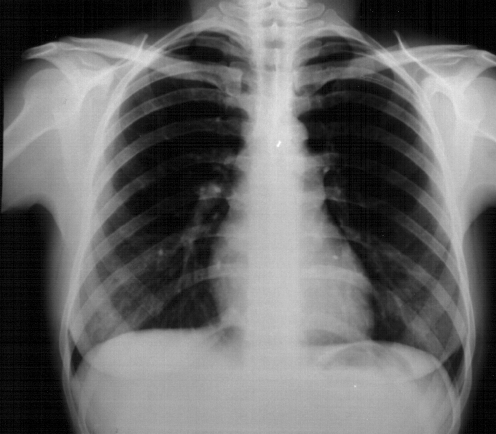

Fig. 1.

Giant cell tumour of the left distal humerus in a 30-year-old female patient

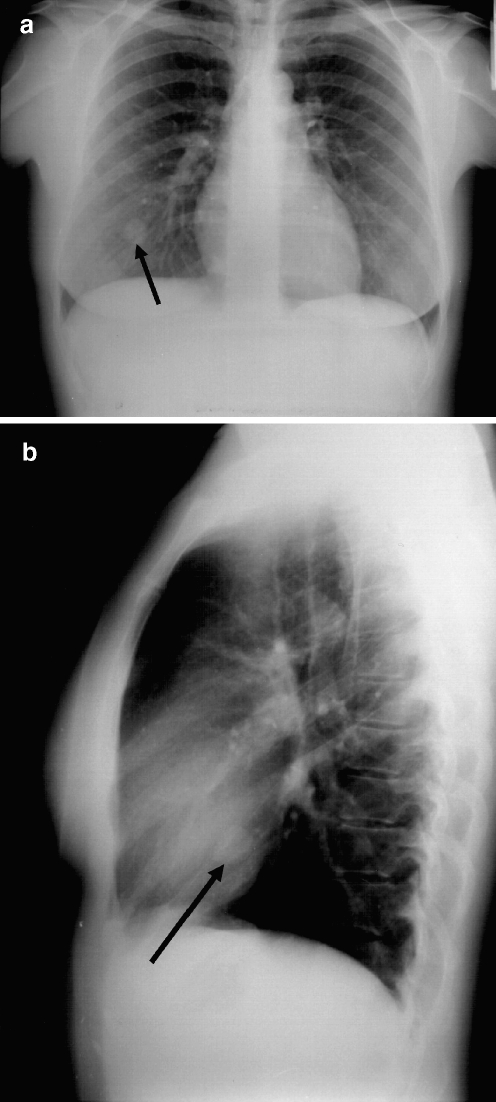

Fig. 2.

X-ray of the lung at the time of first presentation

Fig. 3.

a X-ray of the lung 4 years later presenting a 3-cm metastasis in the right lower area. b Lateral view of the chest X-ray (the metastasis is marked by an arrow)

Treatment of metastases was complete excision in 11 patients, biopsy in 2 and incomplete excision in 1. In one patient, a second pulmonary operation (lobectomy) had to be performed 12 months after the metastasectomy of four nodules because of a new solitary nodule. Adjuvant chemotherapy (doxorubicin 75 mg/day for 2 days; three cycles) was performed in two patients, and two patients had an additional administration of calcitonine (100 U/day).

Discussion

Analysing the reports of the larger series published so far, 25% of local recurrences occur within the first 6 months, 97% during the first 2 years, and 100% during the first 3 years [7]. Local recurrence was noted in five of six patients (83%) before or concurrent with pulmonary metastasis [13]. In Tubbs et al.’s series, 7 of 13 patients (54%) developed local recurrence before lung metastases were diagnosed [21]. However, no association was found between the number of surgical interventions and the interval of onset of pulmonary metastases.

In our series, all patients who were treated initially elsewhere were admitted for a local recurrence. Three of them experienced a second local recurrence after curettage, and one patient had a total of four local recurrences before the diagnosis of pulmonary metastases. Of the eight patients who were primarily treated at Rizzoli, four had a local recurrence: three after initial en-bloc resection and one after curettage.

Late recurrences have been published 6 to 30 years after the primary operation [4, 5, 11].

The incidence of lung metastases varied between 1 and 9.1% [7, 13, 17]. Most of the metastases are diagnosed within the first few years, and some authors suspect that they might not be found after 10 years [17, 21].

Lung metastases occurred in two of six patients 3 years after their initial presentation [13]. In larger series, the majority of metastases occurred within 7.5 years (92%) with a maximum interval of 10.7 years [17, 21]. Siebenrock reported one patient with an interval of 24 years [19]. With our series we add another case of late metastases 11.9 years after diagnosis.

Different factors have been argued to determine the ability of these tumours to metastasise.

Many authors suggest metastases to be more frequent in cases of recurrent tumours and in those where surgery for local recurrence has been performed [13, 17]. In fact, our own data show 71% of patients have local recurrence prior to pulmonary metastases and in the remaining 29%, no recurrence occurred before the diagnosis of lung metastases.

Kay reported that all patients who developed lung metastases had curettage as the initial treatment [13]. In our series, only 6 of 14 patients had an initial curettage.

The prognostic value of Enneking’s surgical stage of the tumour can be confirmed by our data, which revealed benign aggressive stage III lesions in all metastatic patients.

Similar to the previously reported cases, we found a slight male predominance, and half of the patients had their primary located around the knee joint. However, only one patient’s initial lesion was the distal radius, which may be in contrast to the findings of other authors [21] who found 54% of the metastatic cases primarily located at the distal radius.

Rare cases of metastases to other sites have been described: the lymph nodes [7], liver, soft tissue [12], brain, mediastinum [14], scalp, kidney and penis.

Vascular embolism does not seem to increase the risk of metastasising [3, 18]. Sladden found vascular invasion in 5 cases out of a total of 11, and none of them metastasised [20].

The report of metastasis in two immunodepressed patients has caused speculation that immunocompetence may protect against metastasis [15].

Surgical excision of lung metastases is now widely accepted as the treatment of choice with excellent long-term survival [1, 8, 9]. Ten out of 14 patients in the current series are free of disease with a mean follow-up of 70 months. Four patients are alive with stable disease, and none of the patients died in the follow-up period. The majority of our patients have only been treated surgically. Only two patients with multiple disseminated lung nodules received additional adjuvant chemotherapy (doxorubicin). One of these patients and one patient who developed his lung metastasis after 143 months were administered additional calcitonine (100 U/day). Radiation therapy was not performed in this series.

In the context of previous reports, we conclude from our findings the necessity of plain X-rays of the chest and CT scans at the time of the first presentation even in benign giant cell tumours. Follow-up investigations are recommended in the same way as usually performed in primary skeletal sarcomas regarding the late onset of local recurrences as well as pulmonary metastases.

References

- 1.Bertoni F, Present D, Sudanese A, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone with pulmonary metastases. Six case reports and a review of the literature. Clin Orthop. 1988;237:275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1987;69-A:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlin DC, Unni KK (1986) Bone tumors. General aspects and data on 8,542 cases. Springfield, Charles C.Thomas 119

- 4.Enneking WF. Musculoskeletal tumor surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exarchou E, Maris J, Assimakopoulos A. Soft tissue recurrence of osteoclastoma. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1989;71-B:432–433. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B3.2722935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finch EF, Gleave HH. A case of osteoclastoma (myeloid sarcoma: benign giant cell tumour) with pulmonary metastasis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1926;29:399. doi: 10.1002/path.1700290408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldenberg RR, Campbell CJ, Bonfiglio M. Giant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of 218 cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1970;52:619–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gresen AA, Dahlin DC, Peterson LF, Payne WS. ‘‘Benign’’ giant cell tumor of bone metastasizing to lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1973;16:531–535. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huvos AG (1991) Giant-cell tumor of bone. In: Huvos AG (ed) Bone tumors: Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Philadelphia, London, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Tokyo, WB Saunders 452–467

- 10.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L, Portis RB. Giant cell tumor of bone. Its pathologic appearance, grading supposed variants and treatment. Arch Pathol. 1940;30:993–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson EW, Dahlin DC. Treatment of giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1959;41-A:895–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joly MA, Vazquez JJ, Martinez A, Guillen FJ. Blood-Borne spread of a benign giant cell tumor from the radius to the soft tissue of the hand. Cancer. 1984;54:2564–2567. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841201)54:11<2564::AID-CNCR2820541143>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay RM, Eckardt JJ, Seeger LL, Mirra JM, Hak DJ (1994) Pulmonary metastasis of benign giant cell tumor of bone. Six histologically confirmed cases, including one of spontaneous regression. Clin Orthop 219–230 [PubMed]

- 14.Lewis JJ, Healey JH, Huvos AG, Burt M. Benign giant-cell tumor of bone with metastasis to mediastinal lymph nodes. A case report of resection facilitated with use of steroids. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1996;78:106–110. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.List AF. Metastatic giant-cell tumor in a man positive for HIV. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:517. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802253180813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osaka S, Sugita H, Osaka E, Yoshida Y, Ryu J, Hemmi A, Suzuki K. Clinical and immunohistochemical characteristics of benign giant cell tumour of bone with pulmonary metastases: case series. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2004;12(1):55–62. doi: 10.1177/230949900401200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock MG, Pritchard DJ, Unni KK. Metastases from histologically benign giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984;66-A:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanerkin NG. Malignancy, Aggressiveness and recurrence in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer. 1980;46:1641–1649. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1641::AID-CNCR2820460725>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebenrock KA, Unni KK, Rock MG. Giant-cell tumour of bone metastasising to the lungs. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998;80-B:43–47. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B1.7875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sladden RA. Intravascular osteoclasts. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1957;39-B:346. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.39B2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tubbs WS, Brown RL, Beabout JW, Rock MG, Unni KK. Benign giant-cell tumor of bone with pulmonary metastases: Clinical findings and radiologic appearance of metastases in 13 cases. AJR. 1992;158:331–334. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.2.1729794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]