Abstract

Due to the advances in oncological therapy, the life expectancy of patients with malignant tumours and the incidence of pathological fractures have increased over the last decades. Pathological fractures of the long bones are common complications of metastatic disease; however, the outcome of different surgical techniques for the treatment of these fractures has not been clearly defined. The aim of this study was to evaluate differences in patient’s survival and postoperative complications after the treatment of pathological fractures of the long bones. Eighty-eight patients with 96 pathological fractures of the long bones were analysed retrospectively. Seventy-five patients with 83 fractures received surgical treatment. The operative treatments used were intramedullary fixation, gliding screws, plate osteosynthesis or arthroplasty. Five patients were still alive at the end of data collection at a median time of 42.5 months, and 16.2% survived 1 year, 7% 2 years and 4% more than 3 years postoperatively. All surgically treated patients had a reduction of local pain and were able to walk after the operation. The overall rate of complications was 8%. Early palliative treatment of pathological fractures of the long bones is indicated in most patients in the advanced stage of metastatic disease. The low complication rate, reduction of local pain and early mobilisation justify the surgical stabilisation of fractures in this cohort of patients.

Résumé

En raison des progrés des thérapies oncologiques l’espérance de vie et la fréquences des fractures pathologiques ont augmentées chez les patients porteurs de tumeurs malignes. Les fractures pathologiques des os long sont une complication de la maladie métastatique et l’efficacité des différentes techniques de traitement chirurgical ne sont pas clairement définies. Le but de cette étude était d’évaluer les différences en terme de survie et de complications selon le traitement. C’est une étude rétrospective de 88 patients avec 96 fractures pathologiques traitées par clou centro-médullaire, vissage, plaque vissée ou arthroplasty. Cinq patients étaient encore en vie à la fin de l’étude avec une médiane de 42,5 mois; 16,2, 7 et 4% avaient survécu respectivement 1, 2 ou 3 ans ou plus. Tous les patients traités chirurgicalement avaient des capacités de déambulation et une réduction de leurs douleurs après l’opération. Le taux global de complications était de 8%. Le traitement palliatif précoce des fractures pathologiques des os longs est indiqué chez la plupart des patients à un stade avancé de la maladie métastatique. Le faible taux de complications, la réduction des douleurs et la mobilisation précoce justifient la stabilisation chirurgicale chez ces patients.

Introduction

Pathological fractures of the long bones are a common complication of metastatic disease caused by a variety of primary malignant tumours. The incidence of the metastatic bone deposits by primary malignancies has been reported in up to 50% of the patients [20]. Approximately 50% of primary malignant tumours may affect the skeleton; as a result, the skeleton is the third most frequent site of metastases after the lung and liver [15]. The incidence of bony metastases in advanced breast carcinoma, myeloma and in bronchial, prostate, thyroid and kidney carcinomas has been reported to be between 25 and 100% [9].

The life expectancy of patients with metastatic disease has increased considerably over recent years due to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other oncological treatment methods. The increased life expectancy has led to a higher incidence of bone metastases and the risk of pathological fractures [15]. Pathological fracture of a long bone, especially the femur, is one of the debilitating complications that can occur in a patient with an advanced stage of malignancy.

Many methods have been described to treat pathological fractures of long bones. The use of conventional osteosynthesis methods as opposed to primary arthroplasty. In the upper limb under certain circumstances (e.g., undislocated subcapital fractures and incomplete fractures), conservative therapy is an additional treatment option. However, the exact role of different surgical techniques for the treatment of pathological fractures with respect to the outcome and patient benefit has not been clearly defined. The aim of this study was to evaluate patient survival and postoperative complications after the treatment of pathological fractures of the long bones.

Patients and methods

We studied a consecutive series of patients with one or more pathological fractures of the long bone treated between 1992 and 2005 at the Department of Traumatology of the Medical University of Vienna retrospectively. Eighty-eight patients were identified with a total of 96 long bone fractures.

There were 52 women and 36 men with a median age of 66 years (range: 39–93 years). Breast carcinoma was the most common primary tumour (41%), followed by bronchial carcinoma (18%), prostate carcinoma (11%), multiple myeloma (6%) and other tumours (24%). In 6% of the patients, the primary tumour was diagnosed after the pathological fracture. Multiple metastases were diagnosed in 74% of the patients at the time of operation. At the time of fracture, 61% of the patients had received radiotherapy, 56% had received chemotherapy and 54.5% had already had a surgical procedure to treat the primary tumour. There was no case of impending fracture among the patients.

The most common site of fracture was the femur, with 71% of all fractures (68/96), followed by the humerus in 28% (27/96) of the fractures. A fracture of the proximal tibia occurred in one patient.

Bilateral femoral fractures occurred in four patients, and bilateral humeral fractures occurred in one patient. Additionally, one patient experienced bilateral femoral fractures and a fracture of the humerus. Another patient had a fracture of the humerus and femur and a fracture of one vertebral body.

In this study, patient benefit was defined as early ambulation, pain reduction, a low rate of implant failure, a low complication rate and a long phase of postoperative survival.

Treatment

Thirteen patients were treated conservatively: there were four femoral fractures and nine humeral fractures. Three of the four femoral fracture patients who were treated conservatively had multiple medical problems and were unsuitable candidates for surgical fixation. The other femoral fracture patient treated conservatively declined the offer of surgical fracture fixation. In the nine humeral fracture patients treated conservatively, six were considered unfit for surgical fixation and three patients with undislocated subcapital fractures were treated conservatively in view of the good results possible with conservative management.

The remaining 75 patients with 84 fractures underwent operative treatment. The median interval between the occurrence of the pathological fracture and operation was 1 day (range: 0–20 days). The operative procedure was based on fixation with intra-lesional curettage or without intra-lesional curettage with or without the use of cement. En bloc resection of the metastasis with prosthetic reconstruction was performed in patients who were considered to have a better prognosis and who were fit to undergo extensive surgery. En bloc resection and reconstruction was also performed in patients with a large bone lesion where conventional fracture fixation was not possible.

The spectrum of the implants consisted of intramedullary and extramedullary fixation devices and prostheses (Table 1).

Table 1.

The spectrum and number of the implants used

| Site | Intramedullary nail | Prosthesis | Plate | DHS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur | |||||

| Neck | 0 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 17 |

| Trochanter | 12 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 17 |

| Subtrochanter | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Diaphysis | 22 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 23 |

| Distal | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Humerus | 11 | 1 | 6 | 18 | |

| Tiba | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Total | 53 | 18 | 7 | 6 | 84 |

Intramedullary fixation was performed in 50 patients with 53 fractures. Reconstruction with a plate was achieved in seven patients with six fractures of the humerus and one fracture of the femur. In six patients with six fractures of the proximal femur, a dynamic hip screw was used.

Endoprosthetic replacement was performed in 18 patients with 16 fractures of the proximal femur, 1 fracture of the distal femur and 1 fracture of the humerus: 12 hemiarthroplasties (2 with long stems), 2 total hip arthroplasies and 4 tumour prostheses.

Statistical analysis Results were expressed as the median. Kaplan-Meier analysis and the Wilcoxon signed rank test were performed for the calculation of the postoperative survival. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

Results

Survival

Sixteen patients were lost to follow-up at 2.4 months (range: 0.1–111.9 months) after the operation, mostly because they were transferred to other centres after the operation.

Five patients were still alive at the end of data collection in December 2005 at a median time of 42.5 months (range: 16.1–71.2 months) after surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data of the living patients

| Gender | Age | Primary tumor | Metastases | Fracture site | Survival after fracture (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 66 | Leiomyosarkoma | Multiple (skeleton, liver, rectum) | Humerus | 42.5 |

| Male | 61 | Kidney | Solitary (skeleton) | Humerus | 52.8 |

| Female | 38 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Solitary (skeleton) | Hemur | 46 |

| Female | 78 | Thyroid | Olitary (skeleton) | Humerus | 14.6 |

| Female | 77 | Breast | Solitary (skeleton) | Humerus | 71.2 |

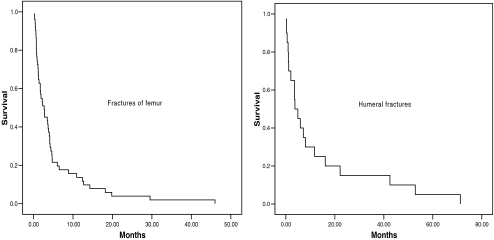

The median survival of all patients after the operation for pathological fracture was 3.2 months (range: 0.2– 29.5 months). The survival rate was 16.2% at 1 year, 7% at 2 years and 4% at 3 years after the operation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Survival curves of all patients with pathological fracture of the long bone

The subgroup of patients with pathological fracture of the humerus had a median survival of 3.7 months (range: 0.2–71.2 months). The survival rate was 25% 1 year after the operation and 15% 2 and 3 years after the operation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Survival curves for patients with fracture of the femur and fracture of the humerus

The subgroup of patients with pathological fracture of the femur had a median survival of 2.7 months (range: 0.2–46 months). The survival rate was 13.7% 1 year after the operation, 4% 2 years after and 2% after 3 Fig. 2). There was no statistically significant difference in survival between humeral and femoral fracture patients, (P=0.8).

Pain relief

The three patients with a conservatively treated humeral fracture reported a reduction of pain after closed reduction and immobilisation in a Gilchrist sling.

All patients undergoing surgical fracture fixation had local pain; however, most of the patients suffered from pain related to the primary disease, requiring analgesic therapy.

Ambulation

Following surgical fixation of lower limb fractures, mobilisation was commenced on the second postoperative day under the supervision of a physical therapist. All patients with surgically treated humeral fractures regained stability and at least limited use of the arm by the day of discharge.

Complications Two patients suffered severe systemic complications after surgery: one patient died from pneumonia 7 days after fixation by γ-Nail fixation of a proximal femoral fracture, and the second patient died 24 days after a long stem hemi-arthroplasty from a pulmonary embolus.Local complications were observed in five patients: One patient suffered an irreversible radial nerve palsy following plate osteosynthesis of an humeral fracture. One patient with a distal femural fracture treated with tumour prosthesis suffered an aseptic wound dehiscence 42 days postoperatively, which was treated with secondary wound closure. One case of deep infection occurred after intramedullary fixation of a tibial fracture. Control of the infection was achieved by antibiotic therapy, operative debridement and removal of one of the interlocking screws (the sagittal proximal screw, which had perforated the skin).A conversion from a DHS to a total hip arthroplasty was performed in one patient after the lag screw cut out of the femoral head. Lastly, one patient with a tumour prosthesis suffered a dislocation 50 days after surgery, requiring a revision operation. The overall rate of complications was 8% in the reported series of patients.

Discussion

The incidence of the pathological fractures of the long bones is approximately 10% in patients with bone metastases [5, 9, 16, 25, 26]. Breast carcinoma was the most frequent primary cause of metastases in our patients (41%), followed by bronchial carcinoma (18%), prostate carcinoma (11%) and multiple myeloma (6%).

Pathological fracture of the bone due to a metastatic deposit often heralds the final stages of the tumour disease and may indicate that the malignant process is in its terminal stage. Ultimately, it is the progression of the primary disease that is the cause of death, with the majority of these patients having a very limited life expectancy. Therefore, a realistic estimation of the life expectancy is essential for planning an appropriate fracture treatment strategy for each patient.

A look at our data shows that only 4.5% of our patients survived a period of more than 3 years. Our results are in keeping with the long-term results of the two Swedish studies describing 192 patients treated surgically for 228 metastatic lesions of the long bones and 142 patients surgically treated for metastatic lesions of the proximal femur [25, 26]. Furthermore, analysis of the mid-term survival results of our patients shows a 2-year survival rate of 7%, which is similar to rates reported in earlier studies [25, 26]. However, the early survival of our patients appears to be considerably lower than the survival of the patients in the earlier Swedish studies [25, 26]. In this study, the 1-year survival rate was only 16.2% compared to 30% in pervious studies [25, 26]. Moreover, Böhm et al. reported an even higher 1-year survival rate of 54% in a study of 94 patients with bone metastases of the lower limb, pelvis or spine [5].

All patients in this study had suffered a complete fracture of a long bone, which may partially explain the lower survival rate compared to other studies that also included patients who had prophylactic fixation of impending pathological long bone fractures [1, 2, 25, 26]. It is well established that the prophylactic treatment of impending pathological fractures results in longer postoperative survival than the treatment of complete pathological fractures [17, 24]. Katzer et al. reported that patients who underwent prophylactic stabilisation of impending fractures survived 5.9 months longer than those who were treated for complete pathological fractures [17]. Furthermore, Ward et al. [24] showed that the treatment of impending pathological fractures yielded better results than the treatment of completed fractures; the postoperative survival was significantly higher in patients with impending pathological fractures compared to those with completed pathological fractures.

Patients with impending pathological fractures had a 1- and 2-year survival rate of 35 and 19%, respectively, compared to those with completed pathological fractures who had 1- and 2-year postoperative survival rates of 25 and 10%, respectively [24]. Ward et al. attributed the improvement to a lower average rate of bleeding, shorter postoperative hospital stay and the higher rate of regaining ambulation in patients treated for impending pathological fractures.

Additionally, the survival differences may also, in part, be due to the different stages of metastatic progression in each reported group. Six percent of the patients in this study suffered a pathological long bone fracture prior to the diagnosis of the primary malignant disease. As a result, these patients presented with advanced-stage malignancy without having had any oncological treatment.

The survival analysis with regard to the fracture site showed a trend towards a better prognosis in patients with pathological fractures of the upper limb than those with a fracture of the lower limb. Patients with humeral fractures had survival rates of 25, 15 and 15% at 1, 2 and 3 years postoperatively, respectively, compared to the patients with femoral fractures with survival rates of 13.7, 4 and 2% after 1, 2 and 3 years postoperatively, respectively. However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Survival analysis related to the primary tumour showed that patients with pathological fractures secondary to breast carcinoma have a tendency to longer median postoperative survival (3.2 months) than patients with other types of primary tumurs, such as prostate (2.2 months) and lung (1.2 months). This is in keeping with the results of earlier studies [18, 19].

The treatment of metastatic bone lesions represents only palliative care in most cases; therefore, an aggressive approach is only justified in selected situations such as for patients with a solitary metastasis (e.g., metastatic lesion from a primary renal carcinoma). However, analysis of our patient group showed almost 75% of the patients with metastatic bone lesions had multiple metastases in different organs and bones.

In this study, we observed a higher percentage of patients with multiple metastases and a lower rate of complications compared to earlier studies in Austrian patient groups [16, 28].

The higher percentage of patients with multiple metastases compared to earlier reports may be the result of the improvement of the current diagnostic methods, while the lower rate of complications may be due to the improvement in intensive care, oncological therapy and surgical techniques.

In this study, the rate of systemic complications was only 2%. Intraoperative complications such as intraoperative death due to fat embolism or intraoperative periprosthetic fractures as well as perioperative complications have been frequently reported in other studies, but were not observed in this study [3, 7, 8]. Pneumonia and pulmonary emboli, each observed in one patient, were the only systemic complications in this cohort of patients. The rate of systemic complications is lower than reported by Wedin et al., with a rate of 4.1%, and is comparable to the 1% reported by Wedin et al. in 1999 [25, 26].

The overall rates of postoperative local complications vary widely with local complication rates ranging from less than 5% to more than 25% [5, 11, 23, 29]. The local complication rate in this study of 5.6% is at the lower end of the scale and is comparable to the 3.4% reported by Wedin et al. [26]. Radial nerve palsy occurred in 5.5% (1/18) of the patients who were operated on for humeral fracture. This is comparable to other reports [12, 13].

Cutting-out of the lag screw within the femoral head is the most commonly reported failure of the sliding hip screws in patients with a “non-pathological” fracture of the proximal femur. The incidence of lag screw migration has been reported to between 1–3% within 6 months of operation and up to 6% within 12–18 months after surgery [6, 14, 21], which is similar to the rate occurring in this patient group.

Dislocation of a tumour prosthesis is a recognised complication following resection of the proximal femur; however, the rate of dislocation in this study was low (6%) and comparable to Clarke et al.’s results [7]. Moreover, they were considerably lower than the 21% dislocation rate of McLaughin et al. in a series of 48 cases [22] and the 13.8% dislocation rate reported by Wiekart and Schwart [27].

The reported rate of other local complications such as deep infection, osteomyelitis and wound healing complications in patients surgically treated for metastases of the long bone have ranged from 1.5 to 9% [16, 25]. The local complication rate in our patient group falls within the range of earlier studies.

It should be appreciated that this study is limited by its retrospective design, the small number of patients and the variety of primary tumours. Due to the small number of patients and the variety of the implants used, it is not possible to define clearly the optimal method of surgical treatment for pathological long bone fractures. However, the low incidence of postoperative complications, reduction of pain and early ambulation, as observed in the study, strongly support operative treatment of pathological fractures of long bones in patients with bone metastases. The treatment of bone metastases is only for palliation in the vast majority of the patients; therefore, an aggressive therapy involving extensive surgery is only justified in selected situations. The timing of surgery is dependent on the patient’s general condition, but ideally should be performed at the first safe opportunity.

References

- 1.Algan SM, Horowitz SM. Surgical treatement of pathologic hip lesions in patients with metastatic disease. Clin Orthop. 1996;332:223–231. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199611000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assal M, Zanone X, Peter RE. Osteosynthesis of metastatic lesions of the proximal femur with a solid femoral nail and interlocking spiral blade inserted without reaming. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:394–397. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barwood SA, Wilson JL, Molnar PR, Choong PF. The incidence of cardiorespiratory and vascular dysfunction following intramedullary nail fixation of femoral metastasis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:147–152. doi: 10.1080/000164700317413111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer HC, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases: prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:143–146. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böhm P, Huber J. The surgical treatment of bony metastases of the spine and limbs. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84B:521–529. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B4.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridle SH, Patel AD, Probe RA, et al. Fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. A randomised prospective comparison of the gamma nail and the dynamic hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:330. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke HD, Damron TA, Sim FH. Head and neck replacement endoprostheses for pathologic proximal femoral lesion. Clin Orthop. 1998;353:210–217. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199808000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole AS, Hill GA, Theologis TN, Gibbons CLM, Willett K. Femoral nailing for metastatic disease of the femur: a comparison of reamed and unreamed femoral nailing. Injury. 2000;31:25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80:1588–1594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1588::AID-CNCR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coley BL, Higinbotham NL. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic lesions in bone. AAOS Instr Cours Lect. 1950;7:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colyer RA (1986) Surgical stabilization of pathological neoplastic fractures. In: Hickey RC, Clark RL (eds) Current problems in cancer. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers 118–168 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Demirel M, Turhan E, Dereboy F, Ozturk A. Interlocking nailing of humeral shaft fractures. A retrospective study of 114 patients. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59:436–442. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.17050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franck WM, Olivieri M, Jannasch O, Hennig FF. An expandable nailing system for the management of pathological humerus fractures. Ach Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:400–405. doi: 10.1007/s00402-002-0428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldhagen PR, Conner DR, Schwarze D, et al. A prospective comparative study of the compression hip screw and the gamma nail. J Orthop Surg. 1994;8:367. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hage WD, Aboulafia AJ, Aboulafia DM. Incidence, location and diagnostic evaluation of metastatic bone disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31:515–528. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinz TH, Stoick W, Vecsei V. Behandlung und Ergebnisse von pathologischen Frakturen. Unfallchirurg. 1989;92:477–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzer A, Meenen NM, Grabbe F, Rueger JM. Surgery of skeletal metastases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00402-001-0359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koskinen EV, Nieminen RA. Surgical treatment of metastatic pathological fracture of major long bones. Acta Orthop Scand. 1973;44:539–549. doi: 10.3109/17453677308989090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs H. Management of pathologic fractures of long bones in malignant disease. Acta Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;92:133–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00397949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis S, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo P. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:6–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung KS, So WS, Shen WY, et al. Gamma nails and dynamic hip screws for pertrochanteric fractures: A randomised prospective study in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:345. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B3.1587874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laughin JR, Harris WH. Revision of the femoral component of a total hip arthroplasty with the calcar–replacement femoral component. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:331–339. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schatzker J, Ha’eri GB. Methylmethacrylate as an adjnct in the internal fixation of pathologic fractures. Can J Surg. 1979;2:179–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward WG, Holsenbeck S, Dorey FJ, Spang J, Howe D. Metastatic disease of the femur: surgical treatment. Clin Orthop. 2003;415:230–244. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093849.72468.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedin R, Bauer HC, Wersäll P. Failures after operation for skeletal metastatic lesions of long bones. Clin Orthop. 1999;358:128–139. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199901000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wedin R, Bauer HC. Surgical treatment of skeletal metastatic lesions of the proximal femur. Endoprosthesis or reconstruction nail? J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87B:1653–1657. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B12.16629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weikert DR, Schwart HS. Intramedullary nailing for impending pathological subtrochanteric fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:668–670. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windhager R, Ritschl P, Rokus U, Kickinger W, Braun O, Kotz R. The incidence of recurrence of intra- and extralesional operated metastases of long tubular bones. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1989;127:402–405. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1044687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yazawa Y, Frassica FJ, Chao EY, Pritchard DJ, Sim FH, Shives TC. Metastatic bone disease. Clin Orthop. 1990;251:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]