Abstract

Cell-cycle phase transitions are controlled by cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). Key to the regulation of these kinase activities are Cdk inhibitors, proteins that are induced in response to various antiproliferative signals but that can also oscillate during cell-cycle progression, leading to Cdk inactivation. A current dogma is that kinase complexes containing the prototype Cdk inhibitor p21 transit between active and inactive states, in that Cdk complexes associated with one p21 molecule remain active until they associate with additional p21 molecules. However, using a number of different techniques including analytical ultracentrifugation of purified p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes we demonstrate unambiguously that a single p21 molecule is sufficient for kinase inhibition and that p21-saturated complexes contain only one stably bound inhibitor molecule. Even phosphorylated forms of p21 remain efficient inhibitors of Cdk activities. Therefore the level of Cdk inactivation by p21 is determined by the fraction of kinase complexed with the inhibitor and not by the stoichiometry of inhibitor bound to the kinase or the phosphorylation state of the Cdk inhibitor.

Keywords: Cyclin-dependent kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21Cip1, cell cycle

In eukaryotic cells all major cell-cycle transitions are controlled by the regulation of the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) (Nigg 1995). In their simplest form, these kinases are composed of a catalytic subunit, termed Cdk and a positive regulatory subunit, termed cyclin (Morgan 1995; Pines 1995). The activity of Cdk/cyclin complexes can be negatively regulated by various mechanisms including binding of specific inhibitory proteins (CKIs) (Morgan 1995; Nigg 1995). The prominent physiological role these inhibitors play is underscored by the observation that numerous antiproliferative signals lead to increased CKI levels and that cells deficient for expression of specific CKIs exhibit defects in cell-cycle control (Sherr and Roberts 1995; Harper 1997; Carnero and Hannon 1998; Hengst and Reed 1998). Two families of CKIs have been described in mammalian cells. Whereas the Ink4 family inhibitors bind specifically to kinases Cdk4 and Cdk6, the Cip/Kip family is inhibitory to a broad range of Cdk/cyclin complexes (Carnero and Hannon 1998). This second family consists of three proteins, p21, p27, and p57 (Hengst and Reed 1998).

p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1/CAP20, the founding member of this family, is induced in a p53 dependent manner in response to DNA damage, accounting for cell-cycle arrest in G1 (Sherr and Roberts 1995; Hengst and Reed 1998). Elevated p21 levels have also been observed in cells during senescence and differentiation (Sherr and Roberts 1995; Hengst and Reed 1998). Surprisingly for a protein that can lead to a block in cell-cycle progression, p21 expression was found to be induced when quiescent cells were stimulated to proliferate (Li et al. 1994; Noda et al. 1994) and moreover the majority of Cdk complexes have been reported to be in complex with p21 even in proliferating cells (Zhang et al. 1994a,b; Harper et al. 1995). To explain this apparent paradox, a model has been proposed suggesting that kinase complexes associated with only one inhibitor molecule remain active and that the inactivation of Cdk kinase complexes by p21 requires association with more than one inhibitor molecule (Zhang et al. 1994a,b; Harper et al. 1995). This model has been supported by studies demonstrating that Cdk complexes immunoprecipitated with p21 antibodies are ‘ kinase active ’ (Zhang et al. 1994a,b; Harper et al. 1995) and can be inhibited by addition of excess p21 (Zhang et al. 1994a,b; Harper et al. 1995).

The amino-terminal Cdk-inhibitory domain of p21 shares an extended degree of sequence identity with the Cdk-inhibitory domain of a related inhibitor, p27 (44% identity in a region of 60 amino acids). It has been shown that the amino-terminal domains of both proteins are sufficient for Cdk inhibition (Toyoshima and Hunter 1994; Chen et al. 1995; Luo et al. 1995). In the course of analyzing inhibition of cyclin A/Cdk2 by p27, we discovered that a single p27 molecule was sufficient for inhibition of one kinase complex (L. Hengst and S.I. Reed, unpubl.). This result was consistent with the three-dimensional structure of a complex of truncated cyclin A/Cdk2/p27 polypeptides determined by X-ray diffraction crystallography (Russo et al. 1996).

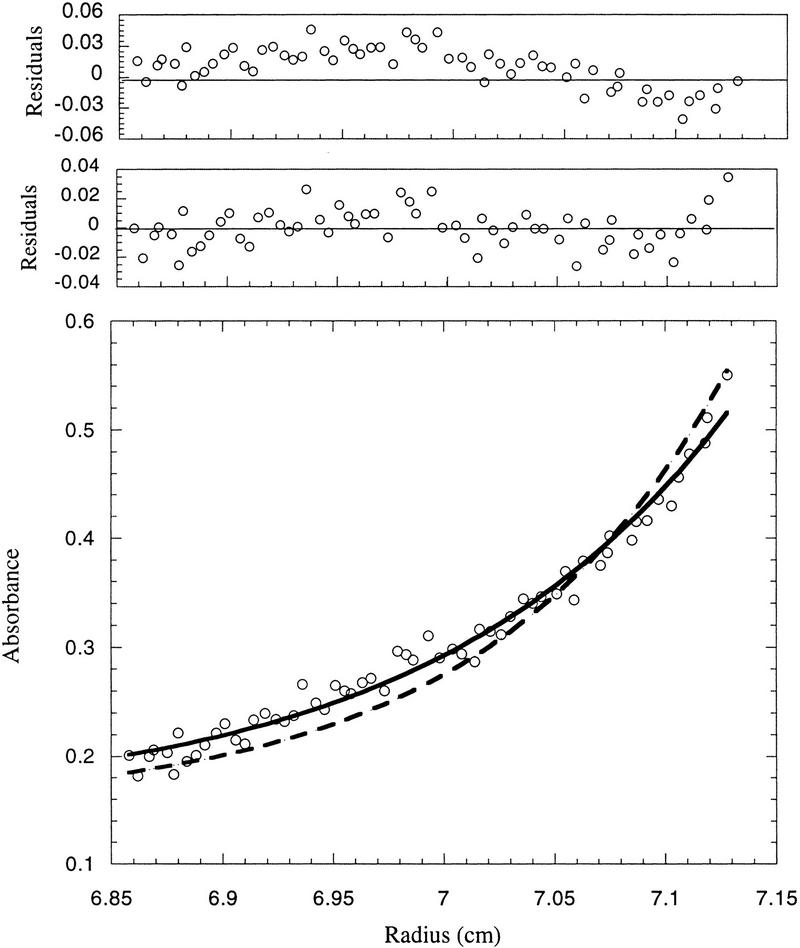

To elucidate the apparent mechanistic difference in Cdk inhibition by p21 and p27, we investigated the inhibition of cyclin A/Cdk2 by p21. To avoid potential artifacts associated with deletions of domains that might contribute to protein interactions, truncated proteins were not used in any of the studies described. We first analyzed bacterially expressed p21 by sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation to ensure it was monomeric under the buffer conditions used for inhibition studies. The concentration distribution data of p21 in the centrifugal field fit to a single ideal species model with a molecular mass of 18,490 ± 772 dalton) (Fig.1), corresponding to a monomeric species (the calculated molecular mass of the HIS-6 tagged p21 is 18,914 daltons).

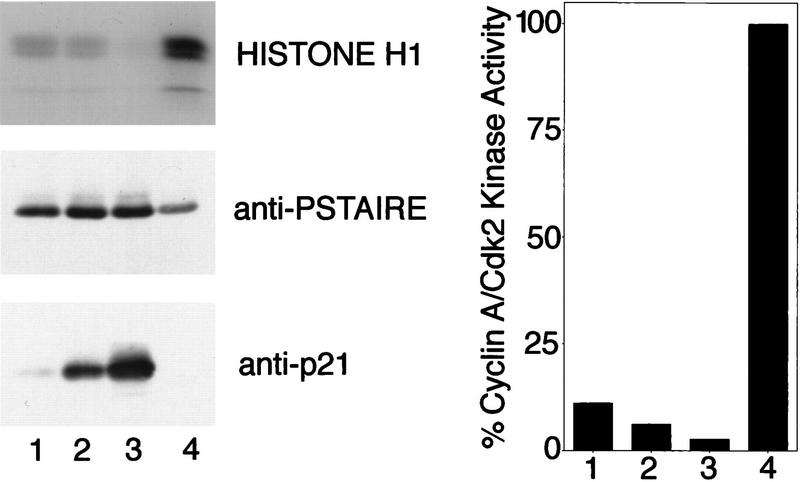

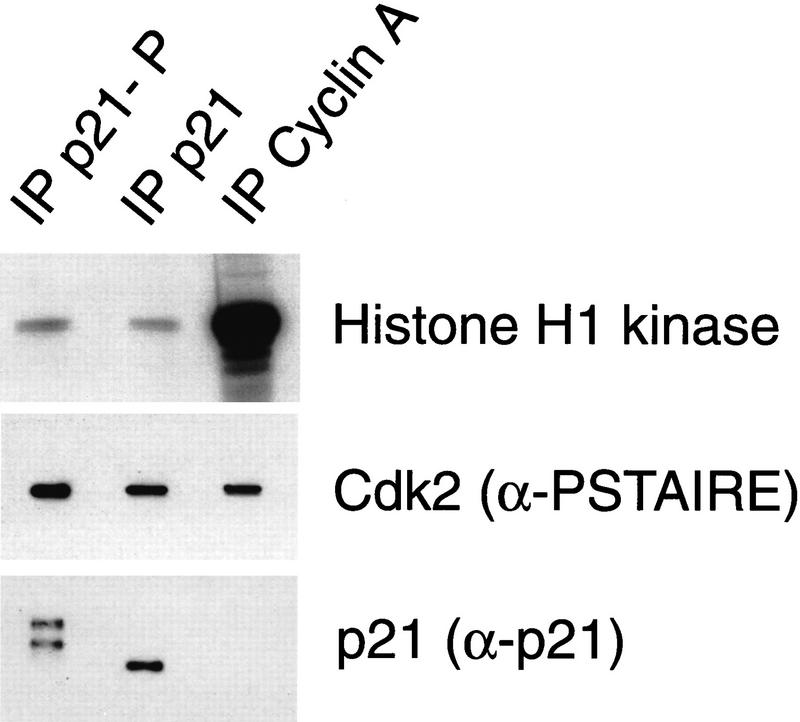

The monomeric p21 was adsorbed to protein A–Sepharose beads via anti-p21 antibodies (directed against a carboxy-terminal peptide known to be dispensable for inhibition). This immobilized monomeric p21 was incubated subsequently with recombinant, full-length, purified and activated cyclin A/Cdk2 to form trimeric, p21-bound kinase complexes on beads. If a stoichiometry of more than one inhibitor molecule per kinase complex were needed for inhibition, the p21-associated Cdk complexes should remain kinase active. The kinase activity of the p21 bound complexes was determined and compared to the activity of noninhibited kinase complexes precipitated directly with anti-cyclin A antibodies and protein A–Sepharose. Normalized for kinase polypeptides, only 6% of the kinase activity of non-p21-bound complexes was retained in complexes bound to p21 beads (Fig. 2, cf. bars 2 and 4). This remaining kinase activity could be reduced slightly to 3% by addition of a twofold excess of soluble p21 protein (Fig. 2, bar 3). These data suggest that a single, bead-associated p21 molecule almost completely inhibits a Cdk complex.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of cyclin A/Cdk2 by immobilized p21. (lanes 1–3) or anti-cyclin A (lane 4) antibodies were bound to protein A–Sepharose beads. These beads were incubated with varying amounts of purified p21: (lane 1) 0.05 μg; (lane 2) 0.2 μg; (lane 3) 0.2 μg; (lane 4) 0 μg. All beads were washed and incubated with ∼ 0.2 μg cyclin A/Cdk2. Nonbound kinase was removed from the beads and the sample of lane 3 was incubated subsequently with additional 0.4 μg of p21. The nonbound p21 was removed and the kinase activities associated with all samples were determined using [γ-32P]ATP and histone H1 as substrates. (Left) The amount of precipitated p21 protein (anti-p21) and Cdk2 (anti-PSTAIRE) was determined in Western blots using monoclonal antibodies. The level of 32P incorporation in the histone H1 bands (histone H1) was determined after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography of the dried gel. The amount of 32P incorporation in the histone H1 bands shown in this autoradiograph was measured using a PhosphorImager. The quantities of precipitated cyclin A and Cdk2 were determined by densitometric scanning of anti-PSTAIRE and anti-cyclin A Western blots and the histone H1 kinase activity of the samples is shown after normalization for the amount of precipitated kinase protein (right).

To exclude a possible dimerization of p21 molecules when bound to the beads, we repeated the experiment with a fourfold lower density of p21 on the beads (Fig. 2, lane 1). Under these conditions, slightly less cyclin A/Cdk2 bound to the p21 beads, indicating that here the amount of immobilized p21 becomes limiting. Again, we found strong inhibition of the kinase activity, most consistent with the conclusion that a single p21 monomer is sufficient to inhibit a cyclin A/Cdk2 kinase complex. Whereas the remaining activity in this experiment (11%) was slightly higher than that in the experiment using more p21 (6%), this is probably because of dissociation and rebinding of the kinase during the assay (see below).

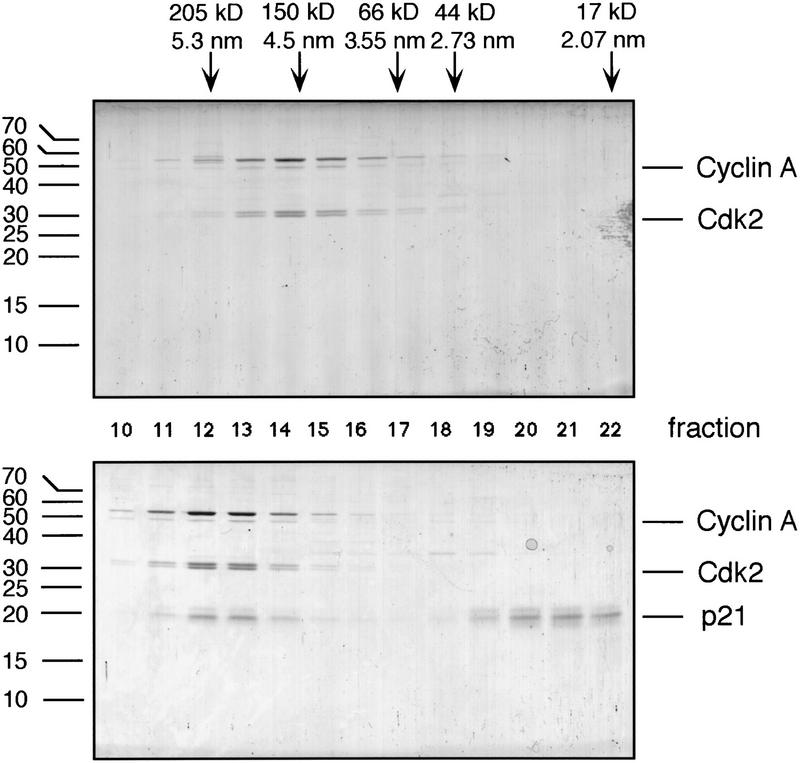

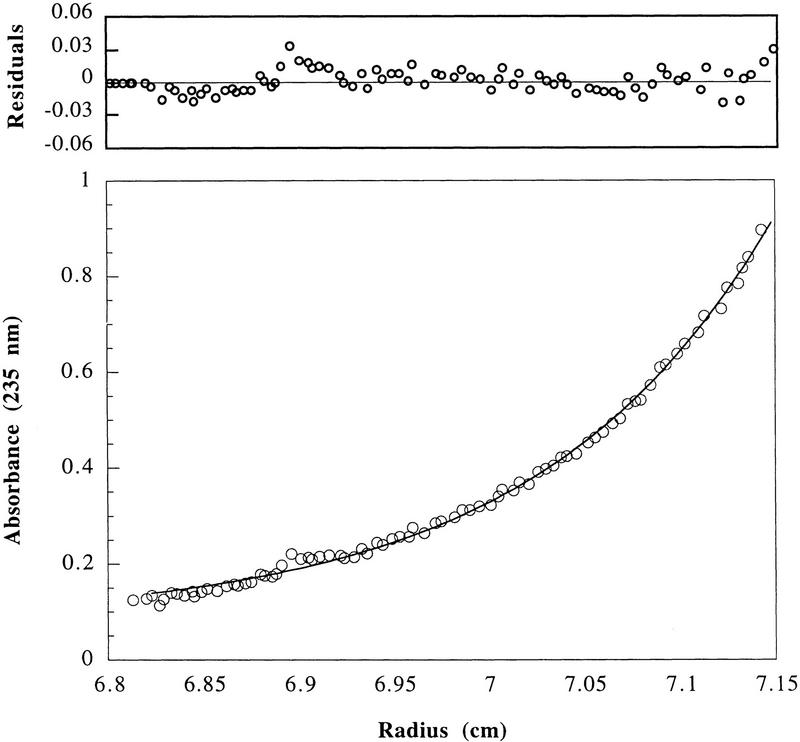

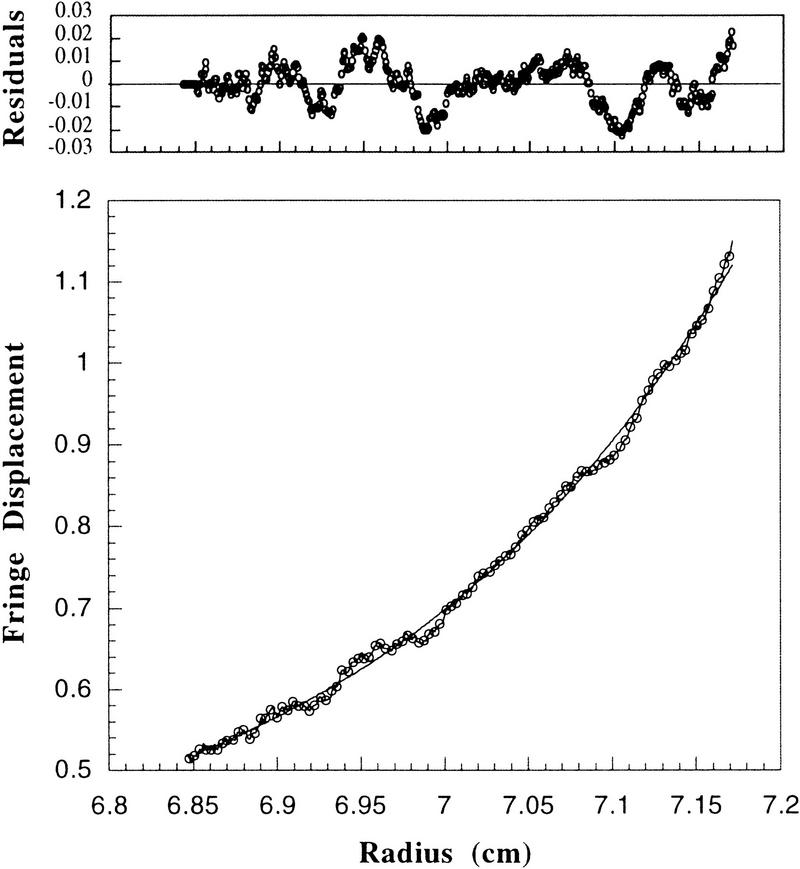

To rule out steric effects of the antibodies used for immobilization of p21, we investigated the inhibition of purified cyclin A/Cdk2 kinase by p21 in solution. Cyclin A/Cdk2 elutes from a gel-filtration column with a Stokes’ radius of 4.72 nm and, thus, an apparent molecular mass >84,955 dalton calculated for the heterodimeric complex of one molecule each of cyclin A and Cdk2 (Fig. 3). However, using analytical ultracentrifugation for equilibrium sedimentation and velocity sedimentation analysis, we found that the buoyant molecular mass for the purified cyclin A/Cdk2 was 86,064 ± 2105 daltons, and is in excellent agreement with the calculated mass (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Size-exclusion chromatography of cyclin A/Cdk2 (top) and p21-saturated complexes of cyclin A/Cdk2 (bottom). Proteins were resolved on a Superdex 200 FPLC column. Aliquots of each fraction were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained using Coomassie blue. The migration of size standards are shown at the left on the gel, and the elution behavior, the Stokes radius, and the apparent molecular mass of marker proteins separated on this column are shown above.

Figure 4.

Determination of the molecular mass of purified cyclin A/Cdk2 by sedimentation equilibrium centrifugation. The apparent molecular mass of the cyclin A/Cdk2 kinase complex was determined as 86 ± 2 daltons. (Bottom) The raw concentration data determined by measuring the absorbance at 235 nm (cyclin A/Cdk2). The solid line drawn through the data points was obtained by fitting the fringe displacement vs. radial position to a single-species model. (Top) The residual differences between the experimental data and the fitted data for each point. The purified proteins used for analytical ultracentrifugation are shown in Fig. 6. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis was performed at 4°C and a rotor speed of 10,000 rpm.

Next, we wished to determine how many p21 molecules can associate with a cyclin A/Cdk2 complex in solution. To saturate all possible binding sites for p21 on cyclin A/Cdk2, we incubated the kinase complex with an excess of the inhibitor. Nonbound p21 was separated from the complex by gel-filtration chromatography (see Fig. 3, bottom, fractions 20–22). The Cdk/p21 complexes appeared homogeneous, as the peak and flanking fractions showed an identical ratio of p21 to cyclin A/Cdk2 (Fig. 3, bottom, lanes 11–14). This was confirmed by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation, as p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 sedimented as a single boundary across the cell, in an excellent fit with a single sedimenting species model (data not shown). To determine whether one or two p21 molecules were bound in this complex, we determined the buoyant molecular mass of the purified p21-containing kinase (shown in Fig. 6A, below) by analytical ultracentrifugation using equilibrium sedimentation. The concentration distribution data fit to a single species model (Fig. 5, solid line), and the molecular mass of the complex was determined to be 105 kD, which is consistent with the presence of a single p21 molecule bound per kinase complex (the calculated molecular mass of this complex is 104 kD). Considering that the maximum error in the determination of the molecular mass in this experiment is ±9 kD, the result is not consistent with a stoichiometry of more than one p21 molecule per Cdk/cyclin complex. To demonstrate this, a theoretical curve modeled to two molecules of p21 per complex is superimposed as a dashed line. It is apparent from comparative fits to the data points and the analysis of residual differences between experimental and fitted data shown above, that the data are much more compatible with a 1:1:1 stoichiometry. From this, we conclude that only a single p21 can stably bind to cyclin A/Cdk2. However, we can not exclude that additional p21 molecules might interact with cyclin A/Cdk2 transiently without forming a stable complex.

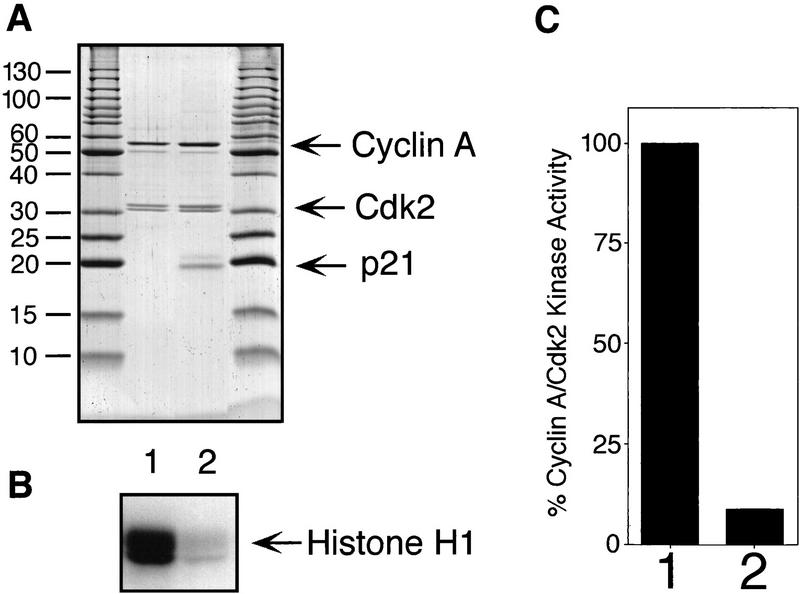

Figure 6.

p21/Cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes are kinase inactive. (A) Purified cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes (lane 1) and p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes (lane 2) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to estimate relative concentrations of their polypeptides (A). Size markers are shown at the sides. The kinase activities of diluted samples (1:100) were determined using [γ-32P] ATP and histone H1 as substrates. The amount of 32P incorporation in the histone H1 bands is shown after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography (bottom) (B) and determined using a PhosphorImager (C). Kinase activities are shown as percentage of that of the noninhibited complexes and were normalized for the kinase subunits present in the complexes. (C).

Figure 5.

Determination of the molecular mass of purified p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes. The apparent molecular mass of cyclin A/Cdk2 complex increases from 86 to 105 kD after saturation of the complex with p21. (Bottom) The raw concentration data determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm. The solid line drawn through the data points was obtained by fitting the fringe displacement vs. radial position to a single-species model. The dashed line represents the predicted behavior of a 1:1:2 (cyclin A:Cdk2:p21) complex using the same single-species model. (Top panels) The residual differences between the experimental data and the fitted data for each point, with those corresponding to the 1:1:2 model placed above those corresponding to the 1:1:1 model. The purified proteins used for analytical ultracentrifugation are shown in Fig.6. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis was performed at 4°C and a rotor speed of 9,000 rpm.

To determine whether the single p21 molecule in these complexes is sufficient for inhibition, we compared the kinase activities of purified cyclin A/Cdk2 and p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes in solution. The relative concentration of the complexes was estimated by Coomassie blue staining of the separated proteins after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A). Only 9% of the activity determined for noninhibitor-bound kinase was found to be associated with the p21-bound kinase (Fig 6B,C). Therefore, one molecule of p21 inhibits a cyclin A/Cdk2 complex efficiently.

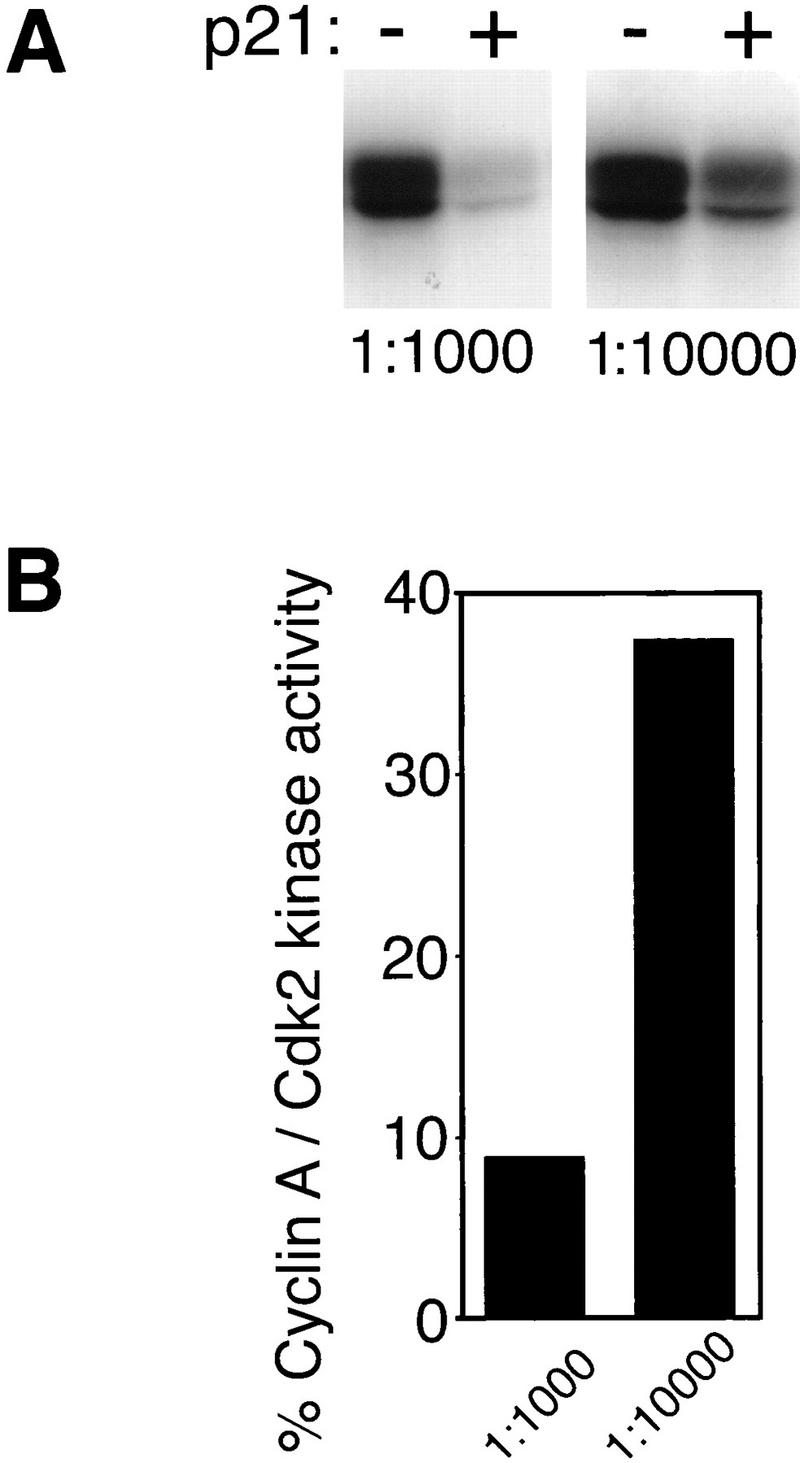

Yet, a low residual activity was observed consistently when the activity of p21-bound kinase was determined. Two possible explanations account for this. First, inhibited complexes might retain an intrinsic kinase activity of ∼10% of that of the noninhibited complexes. If this were the case, dilution of inhibited kinase complexes should not affect the measurable kinase activity. On the other hand, the residual kinase activity of p21-associated complexes could reflect a dissociation/reassociation equilibrium of the kinase complex from the inhibitor during the kinase assay. In this case, it would be expected that the residual kinase activity of p21-saturated cyclin A/Cdk2 would increase if these complexes were diluted prior to a kinase activity assay. The increase in kinase activity upon dilution would result from the lower concentration of p21 available for rebinding of the dissociated active kinase. We found that dilution of p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes can lead to a significant loss of inhibition by p21. As shown in Figure 7, a 10-fold dilution of inhibited, purified p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes under a threshold level led to a dramatic decrease in inhibition. The kinase activity of the diluted complex rose from 9% to nearly 40% of the activity determined for noninhibitor-bound kinase in the same dilution (Fig. 7B). Because the increase of apparent p21-associated kinase activity is obtained without a change in the ratio of p21 to cyclin A/Cdk2, dissociation of kinase without efficient reassociation must account for the loss of inhibition. The degree of residual kinase activity is therefore most likely dependent on the concentration of the pool of unbound p21 that is present or accumulates during the kinase assay. Such considerations need to be factored into the interpretation of kinase assays that are based on immunoprecipitations of CKI or Cdks from cell lysates.

Figure 7.

Inhibition by p21 is lost when inhibited kinase complexes were diluted under a threshold level. The complexes shown in Fig. 5A were diluted 1:1000 (left) and 1:10,000 (right). Kinase activities of p21-bound cyclin A/Cdk2 (+) were compared to that of noninhibited kinase (−) using [γ-32P] ATP and histone H1 as substrates. (A) The amount of 32P incorporation in the histone H1 bands is shown after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography (A). Two different exposures of the same gel are shown. The exposure time shown for the 10-fold diluted samples (1:10,000) is 10 times longer than that for the concentrated sample (1:1000). (B) Histone H1 kinase activities of all samples were determined using a PhosphorImager and the kinase activities of p21-inhibited kinase are shown as a percentage of that of noninhibited kinase and are normalized to the relative kinase subunit concentrations (B).

In addition to its role as a CKI, p21 has also been suggested to be a substrate for Cdks. Phosphorylation of p21 might potentially alter its ability to bind and inhibit kinase complexes. Phosphorylation of a Cdk-inhibitor by its target Cdk was previously described for p27. When p27 is incubated with cyclin E / Cdk2 kinase, a phosphorylation of the inhibitor on threonine residue 187 was observed, resulting in the elimination of p27 from the cell (Sheaff et al. 1997; Vlach et al. 1997).

There are three potential minimal Cdk-consensus phosphorylation sites in the p21 primary structure. Two forms of different electrophoretic mobility have been observed previously in cyclin A complexes immunoprecipitated from G2/M cells (Dulic et al. 1998). To analyze whether p21 is a substrate of cyclin A/Cdk2, purified p21 was incubated with cyclin A/Cdk2 for an extended period of time. At equimolar stoichiometries of p21 and cyclin A/Cdk2, a phosphorylation event was observed that led to a minor mobility shift of p21 analyzed by SDS-PAGE. This phosphorylation event could be followed most easily by incorporation of radioactive phosphate into p21 (data not shown). Incubation with an excess of kinase led first to the minimally shifted form of p21 that appeared with rapid kinetics (within 15 min of incubation), which was subsequently chased to two additional more slowly migrating forms of p21 (data not shown). Using extended incubation times, all of the p21 could be shifted to these novel forms of lower electrophoretic mobility, corresponding to apparent molecular masses of ∼23 and 25 kD vs. 21 kD for the unmodified protein (Fig. 8). These more slowly migrating forms most likely contain several phosphorylated residues per p21 molecule and were analyzed for Cdk inhibition.

Figure 8.

Phosphorylated p21 is a potent Cdk inhibitor. Phosphorylated p21 was obtained by incubating the inhibitor with an excess of activated cyclin A/Cdk2 and 1 mm ATP. Phosphorylated (p21-P) and mock-incubated, nonphosphorylated p21 (p21) were purified and immobilized on protein A–Sepharose beads as described in Fig. 2. These beads and anti-cyclin A antibodies bound to control beads were incubated with 250 ng of active cyclin A/Cdk2 complex and washed and equal aliquots were analyzed for associated kinase activities (histone H1 kinase) and the amount of precipitated proteins. Precipitated proteins were detected after SDS-PAGE and Western blotting and analyzed for precipitated kinase subunit Cdk2 (Cdk2, α-PSTAIRE) and inhibitor p21 (p21, α-p21). The phosphorylated forms of p21 show a lower electrophoretic mobility compared to nonmodified p21. Precipitated kinase activities associated with these samples were determined in assays using [γ-32P]ATP and histone H1 as substrate and detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography of the dried gel (histone H1 kinase).

When immobilized using antibodies against the carboxy-terminal sequence of p21 and bound to protein A–Sepharose beads, phosphorylated p21 was able to bind cyclin A/Cdk2. Using similar amounts of modified and nonphosphorylated p21, similar amounts of soluble cyclin A/Cdk2 were adsorbed (Fig. 8).

Moreover, phosphorylated p21 is a potent inhibitor of Cdk activity with an inhibition efficiency similar to that of the nonmodified p21 (Fig. 8; >98% inhibition in each case). To exclude a possible dimerization of p21 molecules when bound to the beads, we repeated the experiment with a fourfold lower density of p21 molecules on the beads. Again, we found strong inhibition of the kinase activity using both forms of p21 (data not shown), only consistent with the conclusion that a single p21 monomer is sufficient to inhibit a cyclin A/Cdk2 kinase complex even if p21 is phosphorylated.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

p21 was expressed in Escherichia coli as a carboxy-terminal 6-His–tagged protein as described earlier (Kriwacki et al. 1996). The His6 tag does not interfere with the inhibitory properties of p21 (Kriwacki et al. 1996). p21 was isolated from inclusion bodies by denaturing the insoluble proteins in 8 m urea and purified as a denatured protein using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Quiagen) and Hi-Trap Q column (Pharmacia). The protein was renatured after binding to a Hi-Trap SP column (Pharmacia) and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography in buffer containing 200 mm NaCl and 50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.2 on a Superose 12 column (Pharmacia).

Cdk2 and cyclin A were expressed using baculovirus and insect cells as unmodified (Cdk2) and amino-terminal 6-His-tagged (cyclin A) full-length proteins. The baculovirus constructs were a gift of D. Morgan (University of California, San Francisco). Using a Dounce homogenizer, cyclin A and Cdk2 were extracted in buffer containing 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 300 mm NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 4 mm AEBSF (PEFA block, Boehringer Mannheim), 1 μg/ml E64, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin. The cyclin A/Cdk2 kinase complex was formed in vitro and activated in the presence of 10 mm MgCl2, 4 mm ATP, and phosphatase inhibitors during a 45-min incubation with insect cell extracts containing baculovirus expressed cyclinH/Cdk7. The cyclin A/Cdk2 complex was then purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, anion-exchange chromatography, and Superdex 200 size-exclusion chromatography.

Fast-performance liquid chromatography on a Superdex 200 column was performed at a flow rate of 1 ml/min in chromatography buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl) and 0.5-ml fractions were collected. Standards for the gel-filtration column were gamma globulin (apparent molecular mass in gel filtration 205 kD, Stokes radius 53 Å) (Andrews 1970), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kD, 45 Å) serum albumin (66 kD, 35.5 Å), ovalbumin (43 kD, 27.3 Å), and myoglobin (17.8 kD, 20.7 Å) (Andrews 1970).

Immunoprecipitations and kinase activity analysis

p21-containing complexes were immunoprecipitated using an antibody raised against a carboxy-terminal domain of the protein (C19, Santa Cruz). Cyclin A was precipitated using the polyclonal antibody T310 described previously (Hengst et al. 1994). Immunoprecipitations and Western blots have been described elsewhere (Hengst et al. 1994). Kinase assays were performed at 30°C for 30 min in kinase assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.2, 10 mm MgCl2) containing histone H1, ATP (as indicated or 200 μm), [γ-32P]ATP, as described earlier (Hengst et al. 1994).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium analysis was performed on a temperature-controlled Beckman XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with a An60Ti rotor and photoelectric scanner at 20°C (p21) or 4°C (p21/cyclin A/Cdk2 and cyclin A/Cdk2 complexes) at rotor speeds of 17,000 rpm (p21), 10,000 rpm (cyclin A/Cdk2), or 9000 rpm (p21/cyclin A/Cdk2). Scans were performed using interference optics (p21) or by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm (p21/cyclin A/Cdk2) or 235 nm (cyclin A/Cdk2), with a step size of 0.001 cm and 25 averaged scans. Samples were allowed to equilibrate for 24 hr and duplicate scans 3 hr apart were overlaid to determine that equilibrium had been reached. The partial specific volume of p21 (0. 73 ml/gram) or the protein complexes was calculated based on the amino acid composition and then adjusted for temperature using the Origin software provided by Beckman. The data were analyzed by a nonlinear least squares analysis using the Origin software provided by Beckman and then fit to a single ideal species model using the following equation:

|

1 |

where Ar is the fringe displacement at radius x a0 is the fringe displacement at a reference radius x0,  is the partial specific volume of p21 or the protein complexes, ρ is the density of the solvent, θ is the angular velocity of the rotor, E is the baseline error correction factor, M is the molecular weight, and R is the universal gas constant.

is the partial specific volume of p21 or the protein complexes, ρ is the density of the solvent, θ is the angular velocity of the rotor, E is the baseline error correction factor, M is the molecular weight, and R is the universal gas constant.

Analysis of phosphorylated p21

p21 (1.5 μg; protein concentrations were estimated after SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining) were incubated for 1.5 hr with 20 μg of activated Cdk2/cyclin A in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris/HCl, 140 mmNaCl, 7.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, and 1× Complete protease inhibitors without EDTA (Boehringer Mannheim) in a reaction volume of 60 μl. As a control, p21 was mock incubated in the presence of ATP but without addition of Cdk.

Phosphorylated and mock-incubated p21 were dissociated and separated from kinase complexes by heat treatment (95°C, 5 min) and immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal anti-p21 antibody, directed against a carboxy-terminal sequence of p21 (C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunecomplexes were recovered using protein A–Sepharose beads (CL4B, Sigma). p21 bound to the beads was incubated with 250 ng of recombinant purified activated cyclin A/Cdk2. It was estimated that p21 or phosphorylated p21 were in a twofold molar excess over the enzyme. To determine noninhibited kinase activities, 250 ng Cdk2/cyclin A were precipitated using a polyclonal anti-cyclin A antiserum (T310), immobilized on protein A–Sepharose beads and analyzed as the p21-bound kinase. Beads were washed twice with IP buffer and once with reaction buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl at pH 7.2, 7.5 mm MgCl2). Matrix-bound proteins were either analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or tested for their associated histone H1 kinase activities as described above.

Figure 1.

Free p21 is a monomer. The buoyant molecular mass of recombinant p21 was determined by sedimentation equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation and is 18,490 ± 772 daltons. A scan after 30 hr is shown. (Bottom) The raw concentration data determined using interference optics and the solid line drawn through the data points was obtained by fitting the fringe displacement vs. radial position to a single species model of equation 1 (see Materials and Methods). (Top) The residual difference between the experimental data and the fitted data for each point shown.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Morgan for the gift of baculovirus expressing cyclin A, cyclin H, Cdk2, or Cdk7; Jeffery Kelly for providing use of the analytical ultracentrifuge; and Frauke Melchior for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a fellowship from the Leukemia Society of America to L.H. and by U.S. Public Health service grant GM46006 and U.S. Army grant DAMD17-94-J4208 to S.I.R.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL sreed@scripps.edu; FAX (619) 784-2781.

References

- Andrews P. Estimation of molecular size and molecular weights of biological compounds by gel filtration. Meth Biochem Anal. 1970;18:1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnero A, Hannon G. The INK4 family of CDK inhibitors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;227:43–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71941-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jackson PK, Kirschner MW, Dutta A. Separate domains of p21 involved in the inhibition of Cdk kinase and PCNA. Nature. 1995;374:386–388. doi: 10.1038/374386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulic V, Stein G, Far D, Reed S. Nuclear accumulation of p21Cip1 at the onset of mitosis: a role at the G2/M-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:546–557. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors. Cancer Surv. 1997;29:91–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai LH, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell CL, Swindell E, Fox MP, Wei N. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:387–400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst L, Reed S. Inhibitors of the Cip/Kip family. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;227:25–41. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71941-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst L, Dulic V, Slingerland JM, Lees E, Reed SI. A cell cycle-regulated inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:5291–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriwacki R, Hengst L, Tennant L, Reed S, Wright P. Structural studies of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 in the free and Cdk2-bound state: Conformational disorder mediates binding diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:11504–11509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Jenkins CW, Nichols MA, Xiong Y. Cell cycle expression and p53 regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Oncogene. 1994;9:2261–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hurwitz J, Massagué J. Cell-cycle inhibition by independent CDK and PCNA binding domains in p21Cip1. Nature. 1995;375:159–161. doi: 10.1038/375159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Cyclin-dependent protein kinases: Key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle. BioEssays. 1995;17:471–480. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda A, Ning Y, Venable SF, Pereira SO, Smith JR. Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:90–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: A biochemical view. Biochem J. 1995;308:697–711. doi: 10.1042/bj3080697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo AA, Jeffrey PD, Patten AK, Massague J, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent -kinase inhibitor bound to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature. 1996;382:325–331. doi: 10.1038/382325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheaff RJ, Groudine M, Gordon M, Roberts JM, Clurman BE. Cyclin E-Cdk2 is a regulator of p27Kip1. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1464–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima H, Hunter T. p27, a novel inhibitor of G1 cyclin-Cdk protein kinase activity, is related to p21. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlach J, Hennecke S, Amati B. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. EMBO J. 1997;16:5334–5344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hannon GJ, Beach D. p21-containing cyclin kinases exist in both active and inactive states. Genes & Dev. 1994a;8:1750–1758. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hannon GJ, Casso D, Beach D. p21 is a component of active cell cycle kinases. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1994b;59:21–29. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]