Abstract

We have investigated, in a prospective study, the outcome of a valgus osteotomy of the tibia in patients less than 60 years of age with arthrosis of the medial compartment and a varus angle of no more than 177.7°. Included in the study were 44 high tibial osteotomies (HTO) performed in 42 patients from 1981 until 1996. There were 35 females (2 bilateral) and 7 males, with an average age of 51 years (range: 30–60 years). Only patients in the first three grades, according to Ahlback’s classification, were included. During a mean follow-up period of 10 years (range: 5–17 years), all but 2 patients experienced pain relief. The average loss of postoperative correction at 10 years was 2.4°. The average postoperative Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Rating System score (HSSK) for patients with excellent or good results was 83.5 points. Survivorship analysis showed a success rate of 80% and 66% at 10 and 15 years respectively, and over 52.8% at 17 years of follow-up. HTO results in redistribution of the main stresses towards normal levels, although normal values are never attained. This is probably the reason why patients experienced good results only in the medium term.

Résumé

Nous avons réalisé une étude prospective sur le devenir des ostéotomies tibiales de valgisation chez les patients de moins de 60 ans, présentant une arthrose du compartiment médial du genou et un varus qui était toujours inférieur à 177,7°. Nous avons inclus dans cette étude 44 ostéotomies tibiales proximales, réalisées chez 42 patients de 1981 à 1996 (35 sujets féminins don’t 2 ostéotomies bilatérales et 7 sujets masculins). L’âge moyen était de 51 ans (entre 30 et 60). Seuls les patients présentant une lésion classée dans les trois premiers grades de la classification d’Ahlback ont été inclus. Après un suivi moyen de 10 ans (entre 5 et 17 ans), tous les patients ont été revus sauf deux. La perte de correction à 10 ans était de 2,4°. Le score HSSK était de 83,5 points (excellents et bons résultats), la courbe de survie a été de 80% à 10 ans et 66% à 15 ans, 52,8% à 17 ans. L’évolution de l’ostéotomie tibiale proximale montre qu’avec le temps se produit une récidive de la déformation ce qui explique de bons résultats uniquement à moyen terme.

Introduction

Proximal tibial osteotomy remains the treatment of choice for patients suffering from medial compartment degenerative arthritis. Mayer (1853) was the first to report tibial osteotomy for the correction of a valgus knee. The use of tibial osteotomy for the treatment of degenerative arthrosis of the knee was initially described in 1958. The osteotomy was “cup shaped,” below the tibial tubercle, and it was combined with osteotomy of the fibula. Some years later, the same technique was performed above the tibial tubercle [16]. The technique was subsequently popularised through the successful use of the Gariepy osteotomy, a closed-wedge osteotomy with excision of the fibula head [9, 11]. Open-wedge osteotomy for the treatment of degenerative arthritis of the medial compartment did not have similar favourable results [2]. In this series, only cases falling into the first three categories of Ahlback’s classification were included, thus representing, a more homogenous group of patients than those so far published. The proximal tibio-fibular syndesmosis was dissected, with excision of its articular cartilage. After removal of the osseous wedge, a valgus stress was applied to the knee and the gap was closed. The osteotomy was fixed securely with one or two staples. Following the first 10 years, a definite functional and radiological deterioration was noticed, indicating that high tibial osteotomy (HTO), for patients under 60 years of age suffering from early arthrosis, gives good results only in the medium term.

Materials and methods

Forty-two patients were selected at random for the prospective study. These patients suffered from medial compartment degenerative arthritis, and underwent proximal tibial osteotomy during the period 1981–1996. There were 35 female (2 bilateral) patients and 7 male patients, and the average age was 51 years (range: 26–60 years). The main preoperative symptoms were increased pain associated with daily activities (use of stairs, sitting and rising from a chair), intermittent swelling of the knee (related to activity), and, in some cases, bowing of the affected leg. The duration of symptoms before the operation ranged from 1 to 4 years. None of the patients had pain at rest. On clinical examination, the mean flexion of the knee was 100°. The mean varus deformity of the knee, as measured on plain roentgenograms in the weight-bearing position, was 177.7°. Only patients in the first three grades of Ahlback’s classification [3] were included in the study. The involvement of the medial compartment of the knee joint is an important factor for the inclusion criteria and irrelevant to the degree of varus deformity or the loss of valgus angle. Fourteen knees were grade 1, 10 were grade 2, and 20 were grade 3. In 13 knees, the average preoperative varus angle was 2°, in 24 knees 3.3°, and in 7 knees 7.4°. The mean varus deformity of knees, as measured on plain roentgenograms in the weight-bearing position, was 4.2°.

A lateral incision was used, and the insertions of the patellar tendon and the proximal tibio-fibular syndesmosis were identified. The proximal cut of the osteotomy was 0.5 cm above the insertion of the patellar tendon, and parallel to the knee joint. The distal cut of the osteotomy was done at the same angle as the desired angle of correction. At this level of osteotomy, 1 cm at the base of the wedge was almost equivalent to 10° of correction.

The anterior cortex was cut with a saw and the posterior cortex with an osteotome. The medial cortex remained intact. The proximal tibio-fibular syndesmosis was dissected, with excision of its articular cartilage. After removal of the osseous wedge, a valgus stress was applied to the knee, which caused a fracture of the medial cortex, and closed the gap. This resulted in anatomical valgus correction of 5–7°. The osteotomy was fixed securely with one or two staples.

Starting from the first postoperative day, the patients were encouraged to perform strengthening exercises for the quadriceps muscle, and partial weight-bearing (with the use of crutches) was allowed. The fragments of the osteotomy healed in a mean time of 7 weeks postoperatively.

Results

The mean follow-up time was 10 years (range: 5–17 years). Two osteotomies were considered failures, as these patients experienced continuous pain after the procedure. Two patients had a superficial postoperative infection and 1 patient had a pulmonary embolism; these cases were successfully managed. In 2 patients, an undisplaced fracture of the medial tibial plateau was fixed with one cancellous screw. In 37 out of 42 patients marked pain relief was obtained, and they were satisfied with the results of the operation. Despite the obvious elongation of the lateral elements during the closure of the osteotomy, no lateral thrust was noticed. The lack of lateral thrust is probably due to the shrinkage of these structures during the postoperative period, providing sufficient support for the lateral part of the knee joint. The average loss of correction for the 42 knees was 3.2°. Nine patients subsequently had successful knee arthroplasty.

The majority of patients regained almost normal function at an average of 6 months after osteotomy, and were pain-free. At 6 months’ follow-up, 2 patients (4.5%) continued to have constant pain and decided to seek advice from another orthopedic unit. At 5 years’ follow-up, 25 patients (27 knees, 61.3%) were classified as having excellent outcomes, 9 patients (9 knees, 20.4%) good, 3 patients (6.8%) fair, and 3 patients (6.8%) poor results. At 10 years’ follow-up, 12 patients (27.2%) had excellent results, 4 patients (9.09%) good, 2 patients (4.5%) fair, and 3 patients (6.8%) poor results. At 10–15 years’ follow-up, 2 patients (4.5%) had excellent results, 6 patients (7 knees, 15.9%) had good results, 5 patients (11.3%) had fair results, and 2 patients (4.5%) had poor results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age and sex of the patients, preoperative and postoperative angle, follow-up time, loss of angle correction, and revisions

| Age and sex of patients | Preoperative angle | Postoperative angle | Follow-up (years) | Loss of correction | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51, female | 185 | 191 | 17 | 5° | |

| 2 | 54, female | 182 | 187 | 17 | 2° | |

| 3 | 52, female | 183 | 188 | 16 | 3° | |

| 4 | 56, male | 182 | 187 | 15 | 7° | Revision |

| 5 | 48, female | 184 | 190 | 15 | 3° | |

| 6 | 60, male | 184 | 189 | 14 | 4° | |

| 7 | 40, female | 180 | 186 | 14 | 6° | Revision |

| 8 | 52, female | 183 | 189 | 14 | 3° | |

| 9 | 59, female | 184 | 190 | 13 | 5° | |

| 10 | 57, female | 184 | 191 | 13 | 4° | |

| 11 | 57, female | 185 | 192 | 13 | 5° | |

| 12 | 51, male | 180 | 187 | 12 | 5° | Revision |

| 13 | 45, female | 184 | 189 | 12 | 3° | |

| 14a | 51, female | 177 | 183 | 12 | 3° | Bilateral |

| 14b | 176 | 185 | 12 | 2° | Osteotomy | |

| 16 | 53, female | 175 | 185 | 11 | 2° | |

| 17 | 54, female | 177 | 186 | 11 | 2° | |

| 18 | 55, female | 176 | 182 | 11 | 3° | |

| 19 | 53, female | 175 | 185 | 10 | 2° | |

| 20 | 55, female | 178 | 184 | 10 | 2° | |

| 21 | 49, female | 176 | 186 | 10 | 3° | |

| 22 | 38, male | 175 | 187 | 10 | 4° | |

| 23 | 32, female | 175 | 181 | 10 | 2° | |

| 24 | 49, male | 177 | 187 | 9 | 3° | |

| 25 | 50, female | 176 | 185 | 9 | 1° | |

| 26 | 54, female | 175 | 180 | 9 | 2° | |

| 27a | 55, female | 176 | 187 | 9 | 1° | Bilateral |

| 27b | 175 | 186 | 9 | 2° | Osteotomy | |

| 29 | 52, female | 175 | 181 | 9 | 4° | Revision |

| 30 | 52, female | 177 | 186 | 9 | 3° | |

| 31 | 53, female | 175 | 184 | 8 | 3° | |

| 32 | 48, female | 176 | 182 | 8 | 2° | |

| 33 | 47, male | 178 | 187 | 8 | 1° | |

| 34 | 50, female | 175 | 180 | 8 | 2° | Revision |

| 35 | 30, female | 176 | 186 | 8 | 4° | |

| 36 | 58, female | 175 | 188 | 8 | 3° | |

| 37 | 51, female | 175 | 182 | 7 | 5° | Revision |

| 38 | 53, female | 174 | 185 | 7 | 3° | |

| 39 | 55, female | 172 | 180 | 7 | 4° | Revision |

| 40 | 47, female | 170 | 181 | 7 | 2° | |

| 41 | 50, female | 173 | 186 | 5 | 5° | Revision |

| 42 | 49, male | 174 | 180 | 5 | 6° | Revision |

| −43 | 52, female | 178 | 186 | 0.6 | 0° | Failure |

| −44 | 60, female | 179 | 187 | 0.6 | 0° | Failure |

| 7,821: 44=177.7° | 8,176: 44=185.8° | Average correction angle 8.1° |

The Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Rating System (HSSK) was used for evaluation of the patients. The average preoperative score (HSSK) was 52 points, the average postoperative score for patients with excellent or good results was 83.5 points, and the average score for patients with fair or poor results was 58.83 points.

With regard to the radiological results (Figs. 1, 2, the mean varus preoperative deformity of knees, as measured on plain roentgenograms in the weight-bearing position, was 4.2°. The average preoperative angle was 177.7° and the average postoperative angle was 185.8°, achieving an average correction angle of 8.1°. Nine knees were overcorrected, with an average angle of 189.8°. The average loss of postoperative correction for 24 knees (23 patients), with a follow-up of 10 years, was 2.8°, and the average loss of postoperative correction for 18 knees (17 patients), with a follow-up of more than 10 years, was 3.7°. Average loss of correction in the series was 3.2°.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative X-rays of a varus knee due to medial compartment arthritis. Postoperative X-rays of the correction at 12 years’ follow-up. Note the enormous osteophytes at the upper and lower patella poles. Nevertheless, the medial compartment is still functioning and the patient is pain-free on walking

Fig. 2.

Preoperative X-rays of a varus knee joint due to medial compartment arthritis. Postoperative correction at 15 years’ follow-up. Tri-compartmental arthritis has developed. The patient complained of pain in his daily activities

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA, USA, http://www.graphpad.com).

Average preoperative angle = 177.7°

Average postoperative angle = 185.8°

Average correction = 8.1°

The preoperative and postoperative means are mean ± SEM 177.8±0.5880, n=44 and mean±SEM 185.6±0.4837, n=44 respectively. The difference between the means is −7.841±0.7614, the 95% confidence interval 6.325 to 9.357, with a p value of <0.0001.

Over-correction in 9 knees with average angle = 189.8°

Average loss of correction = 3.2°

Average loss of correction in patients with follow-up over 10 years = 3.7°

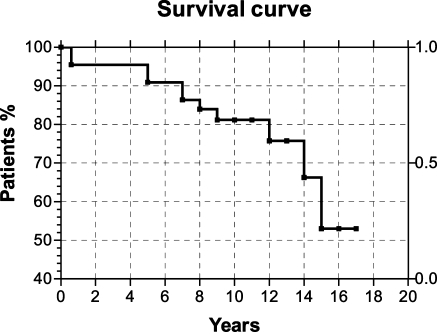

The survivorship analysis showed a success rate of 80% and 66% at 10 and 15 years respectively, and over 52.5% at 17 years’ follow-up (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Survivorship analysis with a success rate of over 52% at 17 years’ follow-up.

Discussion

Proximal tibial osteotomy is the treatment of choice for early degenerative arthrosis of the knee. The results are more favourable if the level of the osteotomy is proximal to the tibial tubercle; the cancellous bone heals rapidly and the risk of nonunion or delayed union is low. Osteotomy was once the only surgical regime giving reliable medium-term results, mainly attributed to the correction of the leg axis and the so-called biological factor. HTO for medial compartment arthrosis has been described extensively [1, 6, 9, 11, 13, 15, 24] There are three types of osteotomy: the open-wedge, the closed-wedge, and the dome-shaped [6]. To achieve the desired degrees of correction, osteotomy of the fibula or detachment of the upper tibio-fibular syndesmosis must first be performed [19]. There is a possible risk of damaging the peroneal nerve [5]. The osteotomy can be fixed securely by staples, plates, and screws, by external fixation or without internal fixation [1, 4, 10, 12, 18].

All operations in this study were performed by the senior author (G.P.), using a lateral wedge excision osteotomy, less than 1 cm above the tibial tubercle, with disruption of the upper tibio-fibular joint. Following closure of the osteotomy, stable fixation was accomplished with one or two staples and the patients were encouraged to carry out weight-bearing activities in order to increase the compression forces at the level of the osteotomy. No cast was used for protection of the osteotomy site because of the security and stability of this technique.

The success of an osteotomy has been attributed to the following factors: correction of the malalignment and unloading of the medial compartment [22], redistribution of load [4], as has been shown by photoelasticity experimental studies [21], and decongestion of the vascular inflow of the area [14].

Some 5- to 10-year studies have shown a tendency to deteriorate [9, 15, 24]. Long-term results of HTO show a progressive deterioration, although there is a discrepancy between good clinical function and a poor radiological appearance [7, 15, 22, 24, 25].

The amount of correction remains a matter of controversy. Overcorrection is recommended by a number of investigators, who have observed better results [9, 17, 20, 25] but, overcorrection may create cosmetic problems or difficulties with future revisions. Average loss of correction in our study was 3.2° and at 10–15 years 3.7°. Overcorrection in our series favourably influenced the long-term results.

Lowering of the patella [22, 23] was not observed, probably because of the small amount of bone removed and the immediate mobilisation of the patients.

Results in our study were correlated with the length of follow-up. Excellent or good results were obtained with 81.7%, 38.6%, and 20.4% of the patients attending the follow-up after 5, 10, and 15 years respectively. There is also a correlation between clinical results and radiological appearance. Patients with fair or poor results complain of pain and reduced activity. The results of this prospective study are similar to those of other studies [2, 4, 5, 8, 13, 22] and demonstrate that the beneficial effects last 10–15 years postoperatively.

What is questionable is the longevity of the good results following osteotomy; in our opinion, good results were fewer than expected in patients suffering early arthrosis.

In a medial compartment knee joint arthrosis, the inclination of the leg axis increases the acting forces in the medial condyles. HTO for knee medial compartment arthrosis restores the axis of the leg and rearranges the contact stresses in the articular cartilage; in fact, it redistributes internal stresses in the condyles and reduces the increased contact stresses in the articular surfaces but does not achieve normal values [21]. This is probably the reason why patients experienced only medium-term good results following corrective osteotomies; in our view it also explains why in cases without severe destruction of the articular cartilage and in patients less than 60 years of age with early return to continuous activities, the beneficial results of the osteotomy do not last for a longer period of time.

Conclusions

High tibial osteotomy is a safe procedure for patients under 60 years of age, suffering early arthrosis, and allows immediate mobilisation. The successful medium-term good results are attributed to the fact that corrective osteotomy redistributes the main stresses toward normal levels, but normal values are never attained. HTO buys time for patients, and allows them to lead a normal life for 10–15 years.

References

- 1.Adili A, Bhandari M, Giffin R, Whately C, Kwok DC. Valgus high tibial osteotomy. Comparison between an Ilizarov and a Coventry wedge technique for the treatment of medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10(3):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s00167-001-0250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agoropoulos Z, Papachristou G, Efstathopoulos N, Karras K, Giannakopoulos P (1989) High tibial osteotomy. Common meeting of the Hellenic Association of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology with the British Orthopaedic Association. 2–6 May, Rhodes

- 3.Ahlback S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;Suppl 277:7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonescu DN. Is knee osteotomy still indicated in knee osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2000;66(5):421–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aydogdu S, Cullu E, Arac N, Varolgunes N, Sur H. Prolonged peroneal nerve dysfunction after high tibial osteotomy: pre- and postoperative electrophysiological study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(5):305–308. doi: 10.1007/s001670000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer G, Insall J, Koshino T. Tibial osteotomy in gonarthrosis (osteoarthritis of the knee) J Bone Surg. 1969;51-A:1545–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouharras M, Hoet F, Watillon M, Dspontin J, Geullete R, Thomas P, Parmentier D. Results of tibial valgus osteotomy for internal femoro-tibial arthritis with an average 8-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Belg. 1994;60:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi HR, Hasegawa Y, Kondo S, Shimizu T, Ida K, Iwata H. High tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis: a 10- to 24-year follow-up study. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6(6):493–497. doi: 10.1007/s007760100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coventry MB. Osteotomy of the upper portion of the tibia for degenerative arthritis of the knee. A preliminary report. J Bone Surg. 1965;47-A:984–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flamme CH, Kohn D, Kirsch L. High tibial osteotomy—primary stability of several implants. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1999;137(1):48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1037035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gariepy R. Genu varum treated by high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Surg. 1964;46-B:783–788. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautier E, Thomann BW, Brantchen R, Jacob RP. Fixation of high tibial osteotomy with the AO cannulated knee plate. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(4):397–399. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giagounidis EM, Sell S. High tibial osteotomy: factors influencing the duration of satisfactory function. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119(7–8):445–449. doi: 10.1007/s004020050018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison MHM, Schajowicz F, Trueta J. Osteoarthritis of the hip: a study of the nature and evolution of the disease. J Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35-A:598–604. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.35B4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insall J, Ranawat CS, Anglietti P, Shine J. A comparison of four models of total knee replacement prostheses. J Bone and Joint Surg. 1976;58-A:754–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson JP, Waugh W. Tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Surg. 1961;43-B:746–751. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kettelcamp DB, Wender DR, Chao EYS, Thompson C. Results of proximal tibial osteotomy. The effects of tibiofemoral angle, stance-phase, flexion-extension, and medial plateau force. J Bone Jt Surg. 1976;58A:952–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan MT, Matthews JG. High tibial osteotomy without internal fixation for medial uni-compartmental osteoarthrosis. Orthopedics. 2000;23(10):1045–1048. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20001001-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurosaka M, Tsumura N, Yoshiya S, Matsui N, Mizuno K. A new fibular osteotomy in association with high tibial osteotomy (a comparative study with conventional mid-third fibular osteotomy) Int Orthop. 2000;24(4):227–230. doi: 10.1007/s002640000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacIntosh DL, Welsh RP. Joint debridement. A compliment to high tibial osteotomy in the treatment of denerative arthritis of the knee. J Bone Jt Surg. 1997;59A:1094–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papachristou G. Photoelastic study of the internal and contact stresses on the knee joint before and after osteotomy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:288–297. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0657-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rinonapoli E, Mancini GB, Corvaglia A, Musiello S. Tibial osteotomy for varus gonarthrosis. A 10- to 21-year followup study. Clin Orthop. 1998;353:185–193. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199808000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scuderi GR, Winsdsor RE, Insall JN. Observations on patellar height after proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Jt Surg. 1989;71A:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vainiopää S, Laike E, Kirves P, Tiusanen P. Tibial osteotomy for osteoarthitis of the knee. A five to ten year follow-up study. J Bone Jt Surg. 1981;63A:938–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valenti JR, Calvo R, Lopez R, Canadell J. Long term evaluation of high tibial osteotomy. Int Orthop. 1990;14:347–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00182642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]