Abstract

When surgically treated, pelvic-ring deformities due to post-traumatic malunions in adults usually require invasive three-stage (prone/supine/prone or supine/prone/supine) procedures. A standardised two-stage prone/supine procedure was developed by the authors. Technical points and first clinical results are presented. Malunuions related to Tile B and C types of fracture were successfully corrected.

Résumé

lorsque les fractures du bassin avec déformation de l’anneau pelvien nécessitent un traitement chirurgical il peut en résulter des pseudarthroses ou des cals vicieux chez l’adulte, qui nécessitent, habituellement un traitement en trois temps. Un traitement standardisé en deux temps a été développé par les auteurs. Les points techniques et les premiers résultats cliniques en sont présentés. Les pseudarthroses ou les cals vicieux secondaires aux fractures de type Tile B ou C ont été traitées correctement et avec succès.

Introduction

Open reduction and internal fixation are now recommended in the treatment of acute unstable pelvic-ring disruption when possible [1, 9, 13, 14], since untreated injuries [3, 6] or injuries treated using external fixation [7] are sources of malunion and nonunion. Anatomical restoration of the pelvic ring has been correlated with better clinical results [12]. Similarly, delayed surgical treatment of pelvic malunion or nonunion aiming at restoring normal anatomy of the pelvis is worthwhile and improves quality of life [5, 8, 11, 15] in terms of sacroiliac pain, limping due to leg length difference, sitting discomfort, and some non-neurological uro-sexual problems directly related to the pelvic deformity.

Though specific and anecdotal cases have been successfully treated with one-stage intervention [4], all late anterior and posterior reconstruction of the pelvic ring reported in the literature required major surgery with three-stage interventions, including prone-supine-prone or supine-prone-supine procedures [5, 8, 10, 11, 15]. However, operative duration and consequently operative morbidity could be reduced by limiting these surgical techniques to a prone-supine two-stage-only procedure.

The goal of this paper was to present the technique and the first results of the standardised two-stage reconstruction procedure performed at our institution for treating malunion after pelvic-ring injuries.

Materials and methods

Series

Eight consecutive cases of pelvic malunion were treated using two-stage procedures between May 2002 and May 2004. There were four men and four women patients aged 18–43, on average 8 years after the initial trauma. Classification of the initial lesions was unstable B in two cases and C in six cases according to the Tile classification [13]. The fractured pelvis was initially treated using external fixation in three cases, open reduction and internal fixation in one case, temporary traction in one case, and temporary discharge in one case. In two cases the fracture was essentially not treated. Neurological consequences of the trauma included two cases of urinary incontinence; one patient had partial motor deficit with stepping. All patients suffered from posterior sacroiliac pain in association with severe discomfort on sitting in four cases. There was a significant limb length difference greater than 2 cm in seven cases. Four patients had sexual problems of mechanical origin.

Surgical technique

Two-stage surgery consisted of a primary posterior approach in the prone position for opening the sacroiliac joint and systematically and completely cutting the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments; and a secondary ilioinguinal approach in supine position for releasing the pubic symphisis and the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint, achieving reduction, and performing osteosynthesis of the pubic symphisis and sacroiliac joint, including bone-graft harvesting and grafting.

First stage

The patient was positioned in the prone position on a standard operative table. A vertical skin incision was performed lateral to the sacroiliac joint, so that the scar would not be located at the fulcrum when leaning on the back. The gluteus maximus muscle was vertically detached from the iliac crest posteriorly, at its junction with the erector spinae, to expose the sacroiliac joint. Both sacrotuberous and sacrospinal ligaments were systematically cut safely along the lateral border of the sacrum to its distal end. Depending on the initial lesion of the pelvic ring, the dislocated sacroiliac junction or the sacral alar malunion were progressively opened from posterior to anterior. In the case of a sacral alar fracture, the osteotomy had to be complete from the posterior aspect because the malunion was usually too medial to allow the anterior side to be cut easily later on. For the closure, the aponeurosis of the gluteus maximus was stitched to that of the erector spinae.

Second stage

The patient was then placed in a supine position on a Judet orthopaedic table allowing traction on the inferior limb to pull down the hemiplevis if necessary. An ilioinguinal approach was performed. The middle window (iliofemoral vessels) did not have to be exposed. The lateral window (iliopsoas muscle) was prepared, taking great care to respect the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The elevation of the iliopsoas muscle from the iliac fossa allowed the release of the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint and the sacral ala, where the first-stage posterior procedure ended. The medial window was completed with a Pfannenstiel approach for exposing the superior aspect of the pubic symphysis that was anteriorly and posteriorly released, with specific attention to possible adhesions to the bladder.

Pelvic deformity was corrected using axial traction on the ipsilateral lower limb with the orthopaedic table, and rotational manipulations of the iliac bone with appropriate clamps (e.g., Letournel or Keith-Mayo clamps). Bone graft was taken from the internal aspect of the iliac fossa for filling the sacroiliac osteotomy. Posterior fixation used two percutaneous trans-sacroiliac screws (four cases), or two three-hole screwed plates (three cases), or a combination of those techniques (one case), depending on local conditions [12]. The pelvic symphysis was fixed using a six-hole screwed plate placed superiorly. A four-hole anterior screwed plate was added in cases of sacroiliac plate fixation [2] (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

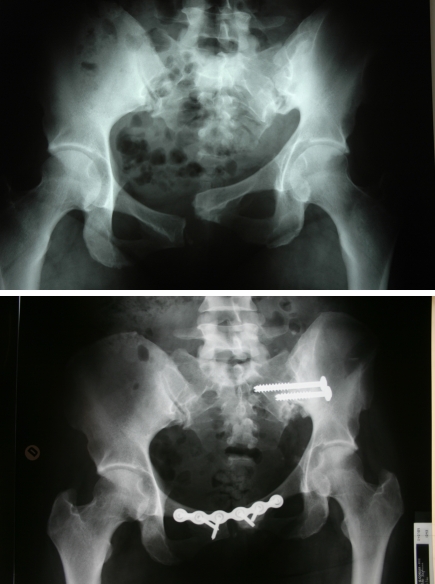

Fig. 1.

Before and after two-stage procedure using two sacroiliac screws and one symphyseal plate

Fig. 2.

Before and after two-stage procedure using two sacroiliac plates and two symphyseal plates

Fig. 3.

Before and after two-stage procedure using a combination of one sacroiliac plate and one sacroiliac screw and two symphyseal plates

Postoperative instructions

No sitting position for 3 weeks, and no weight bearing for 6 weeks.

Patient evaluation

Early surgery-related complications, bleeding, operative time and radiographic reduction were noted. At follow-up, possible clinical after effects and radiological loss of reduction were noted.

Results

Surgery duration was 4.6 h on average. Blood loss required 3.5 blood units perfusion on average including the postoperative period. Perioperative complications included one bladder injury that was immediately repaired without further repercussion. One patient had nosocomial infection in the postoperative period. Three cases of partial motor deficit with drop foot remained at follow-up, those cases had posterior fixation using screwed plates. Anatomical reduction of the malunion was achieved in six cases, but was not complete in two cases.

The average follow-up was 10 months (range: 4–26 months). Overall, the clinical status was improved in five out of eight patients, when compared to their initial condition. Specifically, the posterior sacroiliac pain was relieved in six cases. Mechanical problems due to limb length difference remained in two cases, when reduction was incomplete. Radiologically, one case showed probable posterior nonunion with breakage of one screw in a posterior screwed plate fixation. However, this asymptomatic patient did not present any loss of correction and did not require revision surgery. At follow-up, reduction was maintained in all cases.

Discussion

This paper presents a standardised two-stage surgical procedure, which was successful for treating various types of deformity after pelvic-ring trauma. Early cases showed similar results to those reported with the usual three-stage procedure in terms of reduction of the deformity. The simplified procedure tended to reduce the global morbidity. The concerns about postoperative partial L5-type deficits led to our choice of posterior fixation.

The main goal of pelvic malunion surgery is the restoration of normal symmetrical anatomy of the pelvis. In addition to sacroiliac fusion, reduction of acetabular height, acetabular orientation, and ischial tuberosity height we aim to reduce discomfort on standing, walking and sitting. In these terms, the two-stage technique was successful with various types of deformities including vertical, horizontal, and rotational malunions. Complete reduction was achieved in 75% of cases in our series, while Mears reported 85% anatomical and satisfactory reduction [10], and Matta presented 89% correct reduction using a prone/supine/prone procedure.

We acknowledge, as have others, that pelvic-deformity surgery is invasive and associated with a high rate of complications, including neurological and vascular risks. Matta reported three neurological complications and one vascular complication out of 37 patients [8]. Mears reported eight cases of sciatic palsy in 204 patients; three of them were permanent [10]. We noted three partial sciatic deficits. The use of an anterior endopelvic plate for the fixation of the sacroiliac area (two screws lateral, one screw medial to the osteotomy) was a common feature in these cases. It is possible that this type of fixation puts the lumbosacral trunk at risk during retraction, specifically in cases of post traumatic adhesions. In addition, the fact that the only case of nonunion with breakage of a sacroiliac plate suggests that sacroiliac screws should be used when possible, although the procedure is more demanding technically.

Systematic two-stage procedure tends to reduce blood loss and operating time in comparison with three-stage procedures. Matta et al. [8] reported seven hours of operative time with 1,977 ml of average blood loss. Other authors do not specify operative time and blood loss.

We acknowledge that this study is limited by the number of patients. However, we have demonstrated the feasibility of two-stage prone/supine surgery in various and dramatic pelvic deformities. We emphasise that three-stage procedures are not necessary provided that the primary posterior release is extensive, including systematic complete section of both the sacrospinal and sacrotuberous ligaments. The second key point is the fact that reduction and fixation (anterior and posterior) can be performed under direct vision during the same stage in the supine position, using both the medial and lateral windows of the ilioinguinal approach without dissecting the iliofemoral vessels.

References

- 1.Borrelli JJ, Koval K, Helfet D. Operative stabilization of fracture dislocations of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop. 1996;329:141–146. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comstock C, Meulen M, Goodman S. Biomechanical comparison of posterior internal fixation techniques for unstable pelvic fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(8):517–522. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199611000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebraheim N, Biyani A, Wong F. Nonunion of pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 1998;44(1):202–204. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199801000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frigon V, Dickson K. Open reduction internal fixation of a pelvic malunion through an anterior approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(7):519–524. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200109000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautier E, Rommens P, Matta J. Late reconstruction after pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27(Suppl 2):B29–B46. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(96)89818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gertzbein S, Chenoweth D. Occult injuries of the pelvic ring. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E, Bostman O, Santavirta S. Failure of reduction with an external fixator in the management of injuries of the pelvic ring. Long-term evaluation of 110 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(6):955–962. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B6.8571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matta J, Dickson K, Markovich G. Surgical treatment of pelvic nonunions and malunions. Clin Orthop. 1996;329:199–206. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matta J, Tornetta Pr. Internal fixation of unstable pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop. 1996;329:129–1410. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mears D, Velyvis J. Surgical reconstruction of late pelvic post-traumatic nonunion and malalignment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(1):21–30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B1.13349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennal G, Massiah K. Nonunion and delayed union of fractures of the pelvis. Clin Orthop. 1980;151:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pohlemann T, Gansslen A, Shellwald O, Culemann U, Tscherne H. Outcome after pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27(Suppl 2):S31–S38. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(96)89817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tile M. Pelvic ring fractures: should they be fixed? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:1–12. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B1.3276697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tornetta Pr, Dickson K, Matta J. Outcome of rotationally unstable pelvic ring injuries treated operatively. Clin Orthop. 1996;329:147–151. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderschot P, Daenens K, Broos P. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic pelvic deformities. Injury. 1998;29(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(97)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]