Abstract

That organellar genome variation can play a role in plant adaptation has been suggested by several lines of evidence, including cytoplasm capture, cytoplasm effects in local adaptation and positive selection in a chloroplast gene. In-depth analysis and better understanding of the genetic basis of plant adaptation is becoming a main objective in plant science. Arabidopsis thaliana has all the required characteristics to be used as a model for obtaining knowledge on the mechanisms underlying the role of organelles in plant adaptation. The availability of the appropriate tools and materials for assessing organelle genetic variation will open up new opportunities for developing novel breeding strategies.

Key words: chloroplasts, mitochondria, cytoplasm, cytonuclear interactions, next-generation sequencing technologies, co-evolution, plant breeding, adaptation

Plant adaptation to the environment is becoming an important issue in plant science, from both the basic and applied points of view. In applied plant science, global climate changes and the need for a more sustainable agriculture to supply food to more and more people and in more diverse environments have pressed researchers to assess the capacity for genetic progress in cultivated and wild species.1,2 In basic plant sciences, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies3 and the availability of rich genetic resources are contributing to the growing number of studies designed to decipher the genetic architecture of adaptation.4 In these aspects, model species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana and its relatives, contribute significantly to the development of highly efficient methods for identifying genes underlying ecologically relevant traits, such as traditional linkage mapping and, more recently, genome-wide association mapping.5–10

Most—not to say all—of the above-mentioned studies focus on variation in nuclear genes and very few genetic studies consider the contribution of organelle genomes to adaptation. Nevertheless, a number of reports in various scientific fields provide converging evidence that variations in organelle genomes (either plastids or mitochondria) may indeed contribute to plant adaptation to environmental conditions.

There are two main reasons why organelle genomes have long been disregarded as potential contributors to adaptation. First, these genomes encode a mere 10–15% of the proteomes of their organelles,11,12 and depend on nuclear-encoded factors for their maintenance, transmission and expression. The basic functions of mitochondria and plastids are therefore mainly ensured and regulated from the nucleus, and the well-recognized physiological role of organelles in adaptation has long been considered to involve the genetics of their nuclear components. Second, most proteins encoded in organelles are involved in the structure or assembly of multimeric complexes of the electron transport chains in mitochondria or chloroplasts. Their role in these crucial functions and the strong conservation of the genes that encode them13,14 have led to the assumption that genetic variation affecting the organellar encoded proteins would be eliminated by selection.

In this review, we argue that variation in cytoplasmic genomes contributes significantly to plant adaptation, based on the different types of studies reported in the literature. We think that the time is ripe for investigations on the bases of the organelle genomes' contribution to plant adaptation, and we present some of the exciting and pertinent scientific questions to be addressed in the near future. Finally, we illustrate why the model plant species A. thaliana is, as for many other topics, an excellent candidate species for investigating organellar genome variation and suggest some avenues for further research.

Evidence that Organelle Genomes Contributeto Plant Adaptation

The cytoplasmic contribution to plant adaptation is supported by several lines of evidence, coming from different research fields.

Firstly, some recently reported cases of chloroplast capture are probably driven by the adaptive advantage conferred by the captured cytoplasm. For example, the distribution of chlorotypes in inter-fertile species of the genus Nothofagus sampled in South America tightly correlates with latitude, but not with nuclear phylogeny.15 Another example shows that the cytoplasm of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) has been captured by wild populations of Brassica rapa, one of the parental species of B. napus. Interestingly, B. napus cytoplasm captured by B. rapa occurs significantly more frequently in riverside habitats than in other habitats. The only explanation for this pattern is that a selective advantage is conferred by the B. napus cytoplasm specifically in this habitat.16 However, these studies only used plastid genome markers, and inferring which organelle instigated the cytoplasm capture may be a difficult task because chloroplasts and mitochondria are inherited together.

Secondly, several ecological studies have identified the cytoplasm as a contributor to local adaptation. These studies generally compare the global survival or fitness (seed production) of reciprocal hybrids obtained from two related species that spontaneously hybridize in nature. The difference of behavior in reciprocal hybrids obtained from the same parents, or progeny obtained from these hybrids, indicates that the cytoplasm plays a role in the measured trait. For example, sunflower hybrids between Helianthus annuus, adapted to a moist habitat, and H. petiolaris, adapted to a dry habitat, show differential survivorship in each parental species' native habitat.17 This difference depends largely on the species from which the hybrid progeny received its cytoplasm, leading to the conclusion that the parental species possess locally adapted cytoplasms.17 Likewise, studies on spontaneous and artificial hybrids of Ipomopsis tenuituba and I. aggregata show that the survival of hybrids in each habitat depends on their cytoplasm.18

Interestingly, cytoplasmic local adaptation has also been detected at the within-species level. For example, a significant, albeit subtle effect of cytoplasm was found in the local fitness of Maryland and Illinois populations of Chamaecrista fasciculata, a North American annual legume.19,20 More recently, local adaptation of cytoplasm was observed in a comparison of American and European populations of Arabidopsis lyrata, a relative of the model species A. thaliana.10 These observations indicate that intraspecific variation in the cytoplasm can contribute to adaptive population differentiation.

Finally, amino-acid sequence variation in the plastid-encoded large subunit of Rubisco (ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase oxygenase, the major actor of CO2 assimilation) correlates with the conquest of new ecological niches in the Hawaiian genus Schiedea.21 Furthermore, analysis of rbcL sequences from a wide range of species detected positive selection in its coding sequence, suggesting that its evolution is driven by environmental conditions.22 In this respect, it is particularly interesting to observe that the signature of positive selection is stronger in terrestrial species than in aquatic species, which probably evolved in more buffered environmental conditions.22 Moreover, an analysis of the enzymatic characteristics of Rubisco in a wide range of species also indicated that these characteristics seem to be adjusted to environmental parameters, such as temperature or water availability.23,24 This association suggests that selection can operate on Rubisco activity in particular environmental conditions and that positive selection on specific residues in its sequence can modulate its biochemical characteristics.

Scientific Questions

The above-mentioned reports provide convincing evidence that organelle genomes indeed contribute to plant adaptation and they open two new questions.

First, of the phenotypic traits that are likely to drive selection, which are influenced by variation in organelle genomes? In this respect, the physiological analysis of the cytoplasm background in Ipomopsis hybrids25 is particularly instructive. Reciprocal hybrids reached similar water-use efficiency (i.e., ratio of fixed CO2 to transpired H2O) through different physiological processes. Hybrids carrying the tenuituba cytoplasm had lower transpiration, and lower optimal soil moisture for photosynthesis, whereas those carrying the aggregata cytoplasm had a higher photosynthesis rate.25,26 This example highlights the need to assess the impact of cytoplasm variation on the phenotype at different levels of integration.

Secondly, given the limited number of proteins encoded in organelle genomes and the central importance of the physiological processes in which they are involved, to what extent does organellar genome variation participate in the adaptation process and how is the available range of variation constrained by conservative selective forces? In addition, what constraints are exerted by the nuclear genome on the range of variation in organellar genes? One possibility is that co-adaptation between genetic compartments constrains the range of variation and the phenotypic consequences of this variation. A number of studies that have detected a cytoplasmic effect on fitness or local adaptation also show significant cytoplasm x nuclear genotype interactions.10,17–19 A recent report on the Rubisco large subunit shows that its evolution has been shaped by the combined effect of adaptation and the structural and biochemical constraints that result, at least in part, from functional interactions with nuclear encoded proteins.27

Therefore, the study of “cytoplasmic adaptation” also implies identifying nuclear encoded factors whose variation is coupled with that of cytoplasmic genes as a result of co-adaptation. The most frequently expected situation is a co-adaptive epistasis between the cytoplasm and one (or several) nuclear gene(s).

If we are to address these questions, we need a detailed view of the range of available genetic variation, i.e., how much variation is available in organelle genes, and how much phenotypic variation results from this genetic variation.

Arabidopsis thaliana as a Model to Investigatethe Cytoplasmic Role in Plant Adaptation

We believe that the time has come to genetically dissect the cytoplasmic role in plant adaptation, at least in a species presenting favorable characteristics such as (1) diversity of ecological conditions to which natural populations have adapted; (2) natural genetic diversity of the cytoplasm; and (3) evidence for an effect of cytoplasm or cytoplasm x environment interactions on fitness-related traits. In addition, the availability of rich genetic tools and resources makes for more efficient genetic studies.

A. thaliana meets all the required characteristics for becoming a model species for these investigations on cytoplasmic adaptation. First, natural populations are found in a wide range of habitats, from Norway to the Cape Verde Islands, from the high prairies of Central Asia to Mediterranean or Japanese coasts. Worldwide genotypes collected from natural populations are available in Resource Seed Stock Centers as fixed accessions that can be indefinitely reproduced through selfing. Second, a large amount of information, including information on natural nuclear polymorphism, is available for these genetic resources, and the sequence variation of the whole genome in 1001 accessions is currently under analysis (www.1001genomes.org/). The natural variation in A. thaliana and its relatives has been a growing research field since its nuclear genome has been completely sequenced.7,28,29 Genetic studies exploiting this natural diversity to identify nuclear genes or quantitative trait loci involved in adaptation are beginning to produce results,30,31 and we expect that the number of such studies conducted in the coming years will increase. Unfortunately, to date, only some of these large-scale analyses of sequence variation include organelle genomes.

Our knowledge on cytoplasmic diversity in A. thaliana is much poorer than that of nuclear diversity. Using plastid and mitochondria sequence polymorphisms, we recently analyzed cytoplasmic variability in 95 accessions of A. thaliana and show that organelle genomes have diversified within the species.32 However, the polymorphisms that we used for this study are non-coding sequences, as is usually the case for studies on genome variability and phylogeny. Nevertheless, several studies provide support for a cytoplasmic adaptation role in A. thaliana, as they mention or suggest a cytoplasm effect or a cytoplasm x nuclear interaction effect on traits that may affect fitness. These effects have been shown to influence germination in a study comparing reciprocal F1 hybrids and F1 hybrids crossed with a tester as a father.33 We have also reported a significant effect of the origin of cytoplasm on the germination percentage of reciprocal F2 families.32 Comparisons of reciprocal recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations also reveal that the origin of the cytoplasm in RILs has a significant impact on the segregation distortion of nuclear alleles.34 This observation can be interpreted as an effect of cytonuclear co-adaptation: a non-optimal phenotype resulting from a discordant combination of cytoplasm and nuclear allele(s) results in selection against one parent's allele(s) in one parental cytoplasm, but not in the other. An interesting result on cytoplasm effects is reported from a study that identified QTLs related to water-use efficiency in reciprocal RILs obtained from two natural accessions from very different habitats.5 In contrast to nuclear QTLs, the cytoplasm effect was seemingly contradictory: the cytoplasm from the drought-adapted accession had a negative effect on water-use efficiency compared to the accession from the wet habitat. This observation reinforces the idea that adaptation of cytoplasmic genomes may be limited by their nuclear context. If this situation also occurs in crops, then genetic progress might be enhanced by gearing breeding strategies to the cytoplasm or, even better, to combinations of cytoplasm and nuclear alleles.

We are convinced that investigating the role of the organelle genomes in adaptation is now feasible in A. thaliana and will produce valuable results, both for basic knowledge on plant adaptation and for guiding crop breeders with regard to the future challenges of sustainable agriculture.

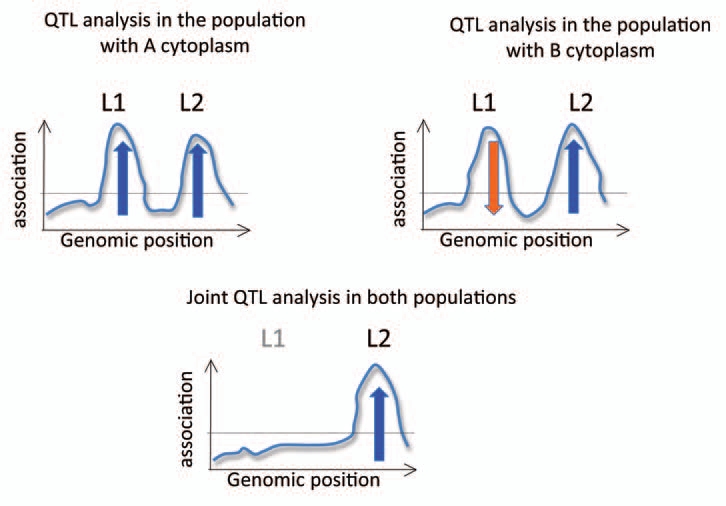

As a first step, a survey of the impact of cytoplasm on the phenotype could be carried out by constituting new genetic resources that combine the nuclear genotype of one accession with the cytoplasmic genomes of another. We will call these new genotypes “cytolines;” they are similar to alloplasmic lines, except that their parents belong to the same species. By evaluating any phenotypic trait of the two cytolines obtained from a reciprocal cross between a pair of accessions with their parental accessions, access is gained to a direct view of the effect of cytoplasm and cytonuclear interactions on this trait. The next step would be to identify nuclear genes that are co-adapted to the cytotypes and that influence the phenotype of interest. A classical QTL mapping approach is appropriate, except that screening would involve identifying a QTL whose allele effect depends on the cytoplasm with which it is combined (see Fig. 1). Once the nuclear gene has been identified, it should provide relevant information on the organelle involved in the cytoplasm effect, which is expected to be that to which the nuclear gene product is addressed, and potentially on the physiological mechanism behind phenotypic variation. Then, relevant organellar genetic variation could be screened for, using a candidate gene approach driven by the knowledge of the function of the co-adapted nuclear gene.

Figure 1.

Use of reciprocal mapping populations to detect nuclear genes co-adapted to cytoplasmic variation. Reciprocal mapping populations (RiLs or F2s) originating from accessions whose cytoplasms (A or B) have a contrasting effect on the phenotype of interest can be used to map QTLs for the target trait. The horizontal line corresponds to the statistical threshold for QTL detection. Vertical arrows symbolize the effect of the A allele on the phenotype. For a nuclear gene whose alleles are co-adapted to the considered variations in the cytoplasm, the effect of parental alleles detected by QTL analysis in the reciprocal mapping populations would appear to depend on the cytoplasmic background. Since parental alleles of a cytoplasm co-adapted QTL (L1) have opposite effects in the parental cytoplasms, this QTL may not be detected when the two mapping populations are analyzed together (bottom graph), but would be detected when each cytoplasm population is analyzed separately (top graphs). in some cases, allelic effects at L1 may only be detectable in one cytoplasmic background but not the other. The positional cloning of the gene responsible for this cytoplasm-dependent QTL could be carried out in the most convenient cytoplasmic background, e.g., the one that shows a more contrasting effect at the QTL. The QTL whose effect does not depend on the cytoplasm (L2) is detected in each cytoplasm population as well as in the global joint population.

Obviously, this type of research program would be considerably facilitated if extended information on organellar genetic variation is made available. Non-synonymous variation can be found in mitochondrial and plastid genes from different accessions (our unpublished work). Whether this genetic variation has an impact on some phenotypic traits remains to be assessed. NGS technologies will soon make it possible to recover organellar variants (the 1001 genomes project; www.1001genomes.org/). Genetic association approaches will then be feasible for identifying cytoplasmic candidate genes whose variation may determine the phenotype. The effect on the phenotype detected for one cytotype can be screened in closely related cytoplasms, and differences in plastid or mitochondrial genomes found between two closely related cytoplasms with contrasted effects on the phenotype will appear as candidates. This approach has been recently successfully used in our group (our unpublished work).

Conclusions and Perspectives

Despite their limited size and number of genes, the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of plants undoubtedly participate in adaptation to environments. It is currently difficult to estimate to what extent organellar genetic diversity determines phenotypic variation, and how much this variation is constrained by genetic and physiological interactions with nuclear gene products. However, organelles' impact on the elaboration of plant adaptive phenotypes has most probably been largely overlooked thus far. A. thaliana appears as an ideal model for analyzing the phenotypic range of variation provided by cytoplasmic genetic variability. Given the availability of organellar genomic variation data and dedicated genetic resources, such as cytolines and reciprocal mapping populations, the genetic dissection of phenotypic variation will soon lead to a mechanistic understanding of the genetic role of organelles in plant adaptation.

This knowledge will in turn provide valuable information crop breeders to evaluate genetic resources and to elaborate new breeding strategies. It will be conceivable to define “elite” cytoplasms, and associated, co-adapted nuclear alleles, according to specific field conditions or to develop breeding targets and strategies. Several studies, which have set out to evaluate the source of different cytoplasms in crop breeding, report a significant impact of cytoplasm and nuclear-cytoplasmic cross-talk on a number of agriculturally relevant traits. For example, cytoplasm and nucleo-cytoplasm interactions have been found for to significantly impact yield and low-temperature tolerance in rice.35

Acknowledgements

We thank Georges Pelletier and Olivier Loudet for critically reading the manuscript and for their stimulating discussions.

References

- 1.Lefebvre V, Kiani SP, Durand-Tardif M. A focus on natural variation for abiotic constraints response in the model species Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:3547–3582. doi: 10.3390/ijms10083547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tardieu F, Tuberosa R. Dissection and modelling of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies—the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergelson J, Roux F. Towards identifying genes underlying ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:867–879. doi: 10.1038/nrg2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mckay JK, Richards JH, Nemali KS, Sen S, Mitchell-Olds T, Boles S, et al. Genetics of drought adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana II. QTL analysis of a new mapping population, KAS-1 x TSU-1. Evolution. 2008;62:3014–3026. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauwels M, Roosens N, Frérot H, Saumitou-Laprade P. When population genetics serves genomics: putting adaptation back in a spatial and historical context. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso-Blanco C, Aarts M, Bentsink L, Keurentjes J, Reymond M, Vreugdenhil D, Koornneef M. What has natural variation taught us about plant development, physiology and adaptation? Plant Cell. 2009;21:1877–1896. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atwell S, Huang YS, Vilhjálmsson BJ, Willems G, Horton M, Li Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature. 2010;465:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature08800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brachi B, Faure N, Horton M, Flahauw E, Vazquez A, Nordborg M, et al. Linkage and association mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana flowering time in nature. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leinonen PH, Remington DL, Savolainen O. Local adaptation, phenotypic differentiation and hybrid firness in diverged natural populations of Arabidopsis lyrata. Evolution. 2010;65:90–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Q, Emanuelsson O, van Wijk KJ. Analysis of curated and predicted plastid subproteomes of Arabidopsis. Subcellular compartmentalization leads to distinctive proteome properties. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:723–734. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millar AH, Heazlewood JL, Kristensen BK, Braun HP, Møller IM. The plant mitochondrial proteome. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe K, Li W, Sharp P. Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast and nuclear DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9054–9058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demesure B, Sodzi N, Petit RJ. A set of universal primers for amplification of polymorphic non-coding regions of mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA in plants. Mol Ecol. 1995;4:129–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1995.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acosta MC, Premoli AC. Evidence of chloroplast capture in South American Nothofagus (subgenus Nothofagus, Nothofagaceae) Mol Phyl Evol. 2010;54:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allainguillaume J, Harwood T, Ford CS, Cuccato G, Norris C, Allender CJ, et al. Rapeseed cytoplasm gives advantage in wild relatives and complicates genetically modified crop biocontainment. New Phytol. 2009;183:1201–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambatti JBM, Ortiz-Barrientos D, Baack EJ, Rieseberg LH. Ecological selection maintains cytonuclear incompatibilities in hybridizing sunflowers. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:1082–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell DR, Waser NM. Genotype-by-environment interaction and the fitness of plant hybrids in the wild. Evolution. 2001;55:669–676. doi: 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0669:gbeiat]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galloway LF, Fenster CB. The effect of nuclear and cytoplasmic genes on fitness and local adaptation in an annual legume, Chamaechrista fasciculata. Evolution. 1999;53:1734–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galloway LF, Fenster CB. Nuclear and cytoplasmic contributions to intraspecific divergence in an annual legume. Evolution. 2001;55:488–497. doi: 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0488:naccti]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapralov MV, Filatov DA. Molecular adaptation during adaptive radiation in the Hawaiian endemic genus Schiedea. PLoS ONE. 2006;20;1:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapralov MV, Filatov DA. Widespread positive selection in the photosynthetic Rubisco enzyme. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galmes J, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Cifre J, Mitchell RAC, Madgwick PJ, et al. Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant Cell Environm. 2005;28:571–579. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tcherkez GGB, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7246–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CA, Campbell DR. Leaf physiology reflects environmental differences and cytoplasmic background in Ipomopsis (Polemoniaceae) hybrids. Am J Bot. 2007;94:1804–1819. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.11.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell DR, Wu CA, Travers SE. Photosynthetic and growth responses of reciprocal hybrids to variation in water and nitrogen availability. Am J Bot. 2010;97:925–933. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T. Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3475–3480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911663107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell-Olds T, Schmitt J. Genetic mechanisms and evolutionary significance of natural variation in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2006;441:947–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baxter I, Brazelton JN, Yu D, Huang YS, Lahner B, Yakubova E, et al. A Coastal Cline in Sodium Accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana Is Driven by Natural Variation of the Sodium Transporter AtHKT1;1. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang X, Schmitt J, Dorn L, Griffith C, Effgen S, Takao S, et al. The earliest stages of adaptation in an experimental plant population: strong selection on QTLS for seed dormancy. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:1335–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moison M, Roux F, Quadrado M, Duval R, Ekovich M, Lê DH, et al. Cytoplasmic phylogeny and evidence of cyto-nuclear co-adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2010;63:728–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corey LA, Matzinger DF, Cockerham CC. Maternal and reciprocal effects on seedling characters in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Genetics. 1976;82:677–683. doi: 10.1093/genetics/82.4.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Törjék O, Witucka-Wall H, Meyer RC, von Korff M, Kusterer B, Rautengarten C, Altmann T. Segregation distortion in Arabidopsis C24/Col-0 and Col-0/C24 recombinant inbred line populations is due to reduced fertility caused by epistatic interaction of two loci. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;113:1551–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tao D, Hu F, Yang J, Yang G, Yang Y, Xu P, Li J. Cytoplasm and cytoplasm-nucleus interactions affect agronomic traits in japonica rice. Euphytica. 2004;135:129–134. [Google Scholar]