Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in dysfunction of the cerebrovasculature. Gap junctions coordinate vasomotor responses and evidence suggests that they are involved in cerebrovascular dysfunction after TBI. Gap junctions are comprised of connexin proteins (Cxs), of which Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 are expressed in vascular tissue. This study tests the hypothesis that TBI alters Cx mRNA and protein expression in cerebral vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Anesthetized (1.5% isoflurane) male Sprague-Dawley rats received sham or fluid-percussion TBI. Two, 6, and 24 h after, cerebral arteries were harvested, fresh-frozen for RNA isolation, or homogenized for Western blot analysis. Cerebral vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells were selected from frozen sections using laser capture microdissection. RNA was quantified by ribonuclease protection assay. The mRNA for all four Cx genes showed greater expression in the smooth muscle layer compared to the endothelial layer. Smooth muscle Cx43 mRNA expression was reduced 2 h and endothelial Cx45 mRNA expression was reduced 24 h after injury. Western blot analysis revealed that Cx40 protein expression increased, while Cx45 protein expression decreased 24 h after injury. These studies revealed significant changes in the mRNA and protein expression of specific vascular Cxs after TBI. This is the first demonstration of cell type-related differential expression of Cx mRNA in cerebral arteries, and is a first step in evaluating the effects of TBI on gap junction communication in the cerebrovasculature.

Key words: connexin, endothelial cells, gap junction, laser capture microdissection, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic injury to the brain often results in injury to the cerebral vasculature. In both humans and experimental animals, traumatic cerebral vascular injury results in impaired cerebral vascular responses to reduced arterial blood pressure and arterial oxygen content and delivery (DeWitt and Prough, 2003; Golding et al., 1999). Autoregulation, cerebral vasodilation or vasoconstriction in response to decreases or increases in systemic arterial blood pressure, respectively, is significantly reduced locally (Lewelt et al., 1980), regionally, and globally after fluid-percussion (DeWitt et al., 1992), as well as other models of experimental traumatic brain injury (TBI; Armstead et al., 2011; Engelborghs et al., 2000; Nawashiro et al., 1995). Cerebral autoregulation is also impaired after head injury in patients (Bouma and Muizelaar, 1990). Although impaired cerebral vascular reactivity after TBI may be the result of a pathological imbalance in the myriad cerebral vasoconstrictors (Armstead, 1999) or vasodilators (Gulbenkian et al., 2001), the underlying causes of cerebral vascular dysfunction after TBI are not well understood.

One potential cause of traumatic cerebral vascular dysfunction is impaired intercellular gap junction (GJ) communication in cerebral vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. This study tests the hypothesis that TBI impairs cerebral vascular reactivity by downregulating connexin (Cx) expression in cerebral vascular smooth muscle and/or endothelial cells, thereby disrupting intercellular GJ communication in these vascular wall tissues. GJs contribute to the repair of blood vessels, and are important for modulation of vasomotor tone (Haefliger et al., 2004) and propagation of vasodilation and vasoconstriction signals (Lagaud et al., 2002a; Segal and Duling, 1989). For instance, inhibitors of GJs attenuate myogenic tone (Lagaud et al., 2002b), and nitric oxide- and acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation (Ujiie et al., 2003) in cerebral arteries, suggesting that GJ communication plays an important role in cerebral arterial tone and vascular reactivity.

GJ coupling is impaired in vascular smooth muscle cells by TBI in vivo (DeWitt et al., 2009; Ohsumi et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2004,2005) or rapid stretch injury in vitro (Hawkins et al., 2009; Sell et al., 2009). Although these results indicate that TBI impairs GJ coupling, the mechanisms of trauma-induced GJ dysfunction are unknown. GJs are low-resistance pathways that permit the passage of low-molecular-weight materials between cells (Loewenstein, 1981). GJs are formed from connexons, hemi-channels in adjacent cells, which are each comprised of six Cx molecules. Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 have been detected in vascular tissues. Vascular smooth muscle cells express all four of these connexins, whereas in rats, endothelial Cx45 has not previously been reported (Figueroa and Duling, 2009; Haefliger et al., 2004). GJ dysfunction can result from reduced phosphorylation of Cx intracellular or extracellular loops (Figueroa and Duling, 2009; Solan and Lampe, 2009), or altered Cx gene and/or protein expression (Figueroa and Duling, 2009), as well as other possible mechanisms (Hesketh et al., 2009).

Thus, we begin the evaluation of TBI's effects on GJ function in the present study by investigating changes in the expression of Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 mRNA and protein in smooth muscle and endothelial cell layers in cerebral arteries harvested from rats subjected to parasagittal fluid percussion TBI or sham injury. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) was used to obtain endothelial or smooth muscle cells for mRNA analyses using ribonuclease protection assay (RPA). This is the first report of the use of LCM to obtain cells from each of the cerebral vascular tissue layers for measuring expression of genes specific to each layer.

Methods

Surgical preparation

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (400–500 g) were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane, intubated, and mechanically ventilated (NEMI Scientific; New England Medical Instruments, Medway, MA) with 1.5–2.0% isoflurane in oxygen/room air (70/30), prepared for parasagittal fluid-percussion TBI as previously described (Dixon et al., 1987), and received either moderate (2 atm) TBI or sham injury (surgical preparation without TBI). Rectal temperature was monitored using a Physitemp Thermalert Model TH-8 (Physitemp Instruments, Inc., Clifton, NJ), and maintained at 37°C throughout the procedure, using a thermostatically-controlled water blanket (Gaymar Industries, Inc., Orchard Park, NY).

mRNA expression studies

Rats were re-anesthetized with 4% isoflurane at 2, 6, or 24 h after TBI or sham injury and decapitated (n=6/group/time point; total n=36). Large cerebral arteries were harvested using a dissecting microscope and stored at −80°C until they were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) medium for sectioning in a cryostat.

Protein determination studies

Rats were re-anesthetized with 4% isoflurane 24 h after trauma and decapitated (n=6/group; total n=12). Blood vessels were harvested as above and stored at −80°C.

Laser capture microdissection

Cells were obtained from cerebral blood vessels using LCM (Hellmich et al., 2007; Shimamura et al., 2004). Frozen 10-μm sections were collected on uncoated RNase-free slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and kept at −20°C until staining. The slides were fixed in 70% ethanol (1 min), rinsed in RNase-free water (15 sec), stained with hematoxylin (15 sec), immersed in 1×automatization buffer (30 sec), rinsed in RNAse-free water (30 sec), dipped in 70% ethanol (30 sec), stained with eosin (30 sec), and dehydrated in 95% ethanol (30 sec), 100% ethanol (twice for 30 sec each), and xylene (twice for 1 min each), then air dried in a hood for 2–4 min, packed with desiccant in a slide box, and stored. Two to 10 endothelial cells and 10 smooth muscle cells from resistance arteries from 4 to 6 sections per animal were captured on separate CapSure® HS LCM Caps (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA), using a PixCell II laser capture microscope (MDS Analytical Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell types were clearly discernible by visual inspection.

RNA isolation, linear amplification of mRNA, and ribonuclease protection assay

Captured cells were treated with lysis buffer and vortexed before the RNA isolation procedure. Total RNA was isolated (RNAqueous Micro Kit; Ambion, Austin, TX), and linearly amplified (MessageAmp Kit; Ambion) following genomic DNA removal with DNase1. Two to 8 μL of RNA and 1 μL of the T7 primer were denatured, and then the first strand of cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription. The single-stranded cDNA was converted into a double-stranded DNA template for transcription, purified through a spin column, and subjected to in vitro transcription for 14 h. The aRNA obtained was DNase treated, purified, and eluted in RNase-free water. Ribonuclease protection assay was performed using 400 ng of linearly-amplified mRNA (HybSpeed RPA kit; Ambion).

Probes were cloned using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as previously described (Shimamura et al., 2004). Sense riboprobes complementary to part of each Cx (connexin 37 [Cx37], connexin 40 [Cx40], connexin 43 [Cx43], and connexin 45 [Cx45]) were radioactively labeled with 32P-UTP. The sizes of the protected fragments were 200, 199, 246, and 297 base pairs, respectively, and the sequences of the primers and probes are listed in Table 1. Samples were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and the size of its protected fragment was 140 base pairs. Separate RPAs for each Cx gene were necessary due to their similarities in size and sequence. All probes were purified by ethanol and subsequently precipitated with 5 mol/L ammonium acetate; 20,000 cpm of each probe was pooled with the internal housekeeping gene probe, co-precipitated with 400 ng of antisense aRNA, denatured, hybridized, and digested with RNase. Protected fragments were run on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in Tris Borate EDTA buffer, then the gels were dried and exposed to a phosphoimaging screen (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Downers Grove, IL) for 1–4 days. Images were scanned using a Cyclone Phosphor Imager (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences), analyzed using OptiQuant image analysis software (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences), and imported into an Excel spreadsheet where all raw data were normalized to GAPDH.

Table 1.

Forward and Reverse Primer and T3 and T7 Probe Sequences Used in Ribonuclease Protection Assays for Expression of Connexin Genes

| Accession number | Gene | Primer and probe sequences |

|---|---|---|

| NM_017008 | Glyceraldeyhyde-3-phosphate | 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ (Forward) |

| 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ (Reverse) | ||

| 5′-GCCTAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGCTGCCAAGGCTGTGGGCAAGGT-3′ (T3) | ||

| 5′-CTCGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTTGATGTCATCATACTTGGCAG-3′ (T7) | ||

| M76532 | Connexin 37 | 5′-GGTCGTCTTCGAATTCGAG-3′ (Forward) |

| 5′-CTCCTCGGTGGTCAAGTTGG-3′ (Reverse) | ||

| 5′-GCCTAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGGCCAGTGGCGTCTCTACGGCT-3′ (T3) | ||

| 5′-CTCGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCGGCTGTCACAGCGGCACAACA-3′ (T7) | ||

| NM_019280 | Connexin 40 | 5′-GAGTTCCTGGAGGAGGTCCA-3′ (Forward) |

| 5′-GAAGACGTTCTTCTCTGTGG-3′ (Reverse) | ||

| 5′-GCCTAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGACGGCACCGCTGCTGAGTCCTCCT-3′ (T3) | ||

| 5′-CTCGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCTGCATGCGCACAGTGTGCATG-3′ (T7) | ||

| NM_012567 | Connexin 43 | 5′-GGTCAACGTGGAGATGCACC-3′ (Forward) |

| 5′-GCTCGCTAGCTTGCTTGTTG-3′ (Reverse) | ||

| 5′-GCCTAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGGCGGCTTGCTGAGAACCTACAT-3′ (T3) | ||

| 5′-CTCGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGTAGAAGAGCTCAATGATGTTC-3′ (T7) | ||

| AF536559 | Connexin 45 | 5′-CGACGCATTCGTGAGGATGG-3′ (Forward) |

| 5′-GGTTGTTCTGGTGATGGTAG-3′ (Reverse) | ||

| 5′-GCCTAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGGTGTCACAGGCCTCTGCCTATT-3′ (T3) | ||

| 5′-CTCGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCAGATCGGCCGGGAGGTGCTCC-3′ (T7) |

Western blot analysis

Cerebral blood vessels were homogenized using a glass homogenizer and 500 μL of homogenization buffer (5 mM EDTA in Ca++-free PBS with protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] per each 50 mL of buffer), then stored at −20°C. Roughly 30 μg of protein extract, as determined by standard BCA (BCA Protein Assay Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL) protein assay, was diluted in 4×sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer and loaded onto a 10% Tris-Glycine gel. Following electrophoresis for 90–120 min at 105 V, the gel was blotted onto a polyvinyldifluoride membrane by overnight electrophoretic transfer at 4°C at 20 V. After preblocking in 5% milk in TBST for 1 h (to reduce nonspecific binding), the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-Cx37 (1:500; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, or 1:250–1:1000; Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX), rabbit anti-Cx40 (1:2000; Invitrogen), rabbit anti-Cx43 (1:2000; Invitrogen), or rabbit anti-Cx45 (1:500; Invitrogen). The membranes were washed for 15 min in TBST, incubated for 1 h at room temperature in horseradish peroxidase-goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:3000; Invitrogen), then washed 3 times (15 min per wash) in TBST. Immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate; Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and were exposed to x-ray film, which was developed for subsequent densitometric analysis using UN-SCAN-IT image analysis software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT). All blots were then normalized to GAPDH (1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, and 1:3000 horseradish peroxidase-goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

Statistical analysis

RPA data were expressed as mean±standard error (SE). Separate one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine differences between groups (sham versus TBI), survival time points (2, 6, or 24 h), and blood vessel cell type (endothelial or smooth muscle). The Fisher protected least squares difference procedure was used for post-hoc analysis. RPA analyses were performed using StatView for Windows software, version 5.0 (1992–1998; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Protein data were not normally distributed and are therefore expressed as quartiles. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test for differences in protein expression between groups (sham versus TBI) for each Cx. For all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of protein data was conducted using SAS software (SAS/STAT® 9.1 user's guide).

Results

There were no significant differences in body weight or temperature between the TBI and sham-injured groups, and no differences in injury levels among the 2-, 6-, or 24-h TBI groups.

Cx mRNA expression

In uninjured rats, the mRNA for all four Cx genes analyzed was detected in both endothelial and smooth muscle cell layers of the cerebrovasculature and was significantly greater in smooth muscle cells compared to endothelial cells (Fig. 1; p<0.01).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of connexin (Cx) mRNA expression in endothelial cells versus smooth muscle cells from cerebral arteries. mRNA for each of the four Cxs in the cerebral arteries of rats is shown. Cells were isolated from uninjured male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=6) using laser capture microdissection to select specific cells from each layer (endothelial layer: 2–10 cells per rat; smooth muscle layer: 10 cells per rat). Data are presented as mean±standard error (*p<0.05 versus corresponding endothelial cells; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; DLU, digital light units).

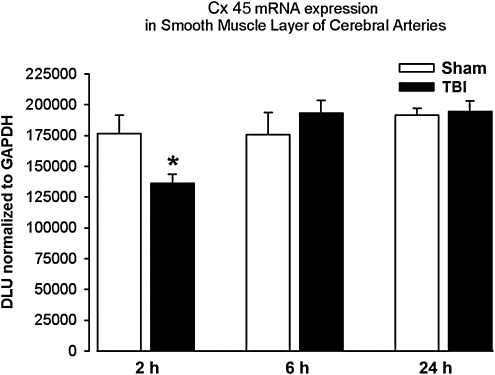

Cx mRNA expression after TBI in vascular smooth muscle cells

In the smooth muscle cell layer, Cx43 mRNA expression was significantly lower (23%) in the TBI group compared to the sham group at the 2-h time point (Fig. 2; p<0.05). There were no significant changes in Cx43 mRNA expression at the 6- or 24-h time points. There were no significant differences in Cx37, Cx40, or Cx45 mRNA expression between sham and TBI animals at the 2-, 6-, or 24-h time points in the smooth muscle cell layer.

FIG. 2.

Connexin 43 (Cx43) mRNA expression in smooth muscle cells. Cells were harvested from the cerebral arteries of male Sprague-Dawley rats at 2, 6, and 24 h after fluid-percussion traumatic brain injury (TBI; n=6/time point) or sham injury (sham; n=6/time point) using laser capture microdissection to select specific cells from the smooth muscle layer. Data are presented as mean±standard error (*p<0.05 versus corresponding sham animals; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; DLU, digital light units).

Cx mRNA expression after TBI in vascular endothelial cells

In the endothelial cell layer, Cx45 mRNA expression was significantly lower (25%) in the TBI group compared to the sham group at the 24-h time point (Fig. 3; p<0.05). There were no significant changes in endothelial Cx45 expression at the 2- or 6-h time points. There were no significant differences in Cx37, Cx40, or Cx43 mRNA expression between sham and TBI animals at the 2-, 6-, or 24-h time points in the endothelial layer.

FIG. 3.

Connexin 45 (Cx45) mRNA expression in endothelial cells of cerebral arteries. Cells were isolated at 2, 6, and 24 h after fluid-percussion traumatic brain injury (TBI; n=6/time point) or sham injury (sham; n=6/time point) using laser capture microdissection to select specific cells from the endothelial layer. Data are presented as mean±standard error (*p<0.05 versus corresponding sham animals; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; DLU, digital light units).

Cx protein expression

Cx protein expression was measured in whole cerebral blood vessels collected 24 h after surgery. Using Western blot analysis, Cx protein expression was detected for Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45 (Fig. 4A). Cx37 protein was not detected despite using multiple dilutions of two different antibodies and clear detection of GAPDH bands (data not shown). Twenty-four hours after surgery, Cx40 protein levels were significantly higher in cerebral blood vessels from rats subjected to TBI compared to sham-injured rats (66%; p=0.016). In contrast, Cx45 protein levels were significantly reduced 24 h post-injury in cerebral blood vessels from rats subjected to TBI compared to sham-injured rats (84%; p=0.037). There was no difference in Cx43 protein levels between sham and injured rats (p=0.749; Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Connexin (Cx) protein expression. Cerebral arteries of rats 24 h following fluid-percussion traumatic brain injury (TBI; T1–T6; n=6) or sham injury (sham; S1–S6; n=6) were evaluated using Western blot (A, upper panel), and densitometrically quantified to compare changes between injury groups (B, lower panel). Data are presented as median (solid line), first and third quartiles (boundaries of box), and range (error bars). The mean is also shown by the dashed lines (*p<0.05 versus corresponding sham animals; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase).

The mRNA and protein data at 24 h are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Cx protein and mRNA Expression Changes at 24 Hours after Traumatic Brain Injury

| |

Protein |

mRNA |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral arteries | Endothelial cells | Smooth muscle cells | |

| Cx37 | ND | NC | NC |

| Cx40 | ↑ 66% | NC | NC |

| Cx43 | NC | NC | NC |

| Cx45 | ↓ 84% | ↓ 25% | NC |

NC, no change; ND, not detected; Cx, connexin.

Discussion

This study is the first step in examining the mechanisms by which TBI disrupts GJ function. TBI was associated with significant reductions in mRNA for smooth muscle Cx43 mRNA at 2 h and endothelial Cx45 mRNA at 24 h post-TBI, as well as significant changes in protein expression at 24 h post-TBI: increased for Cx40 and decreased for Cx45. This is the first report of Cx gene and protein expression in the cerebral vasculature after TBI, and the first quantification of Cx subtype gene expression in rodent cerebral vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells harvested using LCM. To our knowledge, Cx45 has previously only been reported in smooth muscle cells in the rat (Li and Simard, 2001), and thus this is the first report of Cx45 mRNA expression in the endothelial layer of cerebral blood vessels in the rat. The presence of mRNA for all four vascular Cxs (Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, and Cx45) was confirmed, with higher levels of mRNA for each Cx in smooth muscle cells compared to endothelial cells.

Previous evidence suggests that TBI markedly reduces GJ coupling in cerebral arteries; stretch deformation injury reduced GJ coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro (Hawkins et al., 2009; Sell et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2003,2004), and fluid percussion TBI impaired GJ coupling in middle cerebral arteries in vivo (DeWitt et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2005). Given that GJs are comprised of Cxs, we designed the present study to determine whether altered Cx mRNA or protein expression in cerebral vascular tissue after fluid-percussion TBI might be one of the mechanisms by which injury induces alterations in GJ function. Investigation of the expression of Cxs in the cerebral circulation must be done separately from the systemic circulation because cerebral arteries have anatomical and developmental characteristics that are distinct from systemic arteries. Thus investigating cerebrovascular gene expression of Cxs is an important first step in understanding the role of Cxs in maintaining cerebrovascular myogenic tone and in response to traumatic cerebrovascular injury. The production of mRNA is one of the earliest steps in genetic manifestation, leaving room for numerous other means of control at the pre-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels that can be studied in future investigations.

The significant downregulation of mRNA expression of Cx45 observed at 24 h post-injury in the endothelial layer corresponded with a significant decrease in Cx45 protein at 24 h, suggesting a role for Cx45 in prolonged vascular dysfunction after injury. Kochanek and associates reported that controlled cortical impact TBI produced significant reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF), an indicator of cerebral vascular health, which persisted up to a year (Kochanek et al., 2002). Previous reports that the Cx45 protein is important for the development and differentiation of the vasculature such as formation of the vascular tree and development of the smooth muscle layer of major arteries (Kruger et al., 2000), suggest that enhancing Cx45 expression after injury may be related to revascularization or repair. However, other investigators observed an inconsistent correlation between CBF and vascular remodeling after TBI. Hayward and colleagues reported significant changes in CBF and vascular density in rats within 14 days (Hayward et al., 2011) and 8 months (Hayward et al., 2010) after lateral fluid-percussion TBI. Significant hypoperfusion, then normalization of CBF, then subsequent hypoperfusion, were observed along with an increase in cerebral vascular density during the 14-day monitoring period after TBI (Hayward et al., 2011). In contrast, at 8 months post-injury, although CBF and vascular density correlated in a few brain regions (e.g., thalamus), in general, they were not significantly related (Hayward et al., 2010). Although the association between blood vessel density and CBF was inconsistent and appeared to vary with time after TBI, TBI in rodents does result in lasting reductions in CBF and significant vascular remodeling. Although it is unclear whether increasing Cx45 after TBI may improve revascularization, and whether this is beneficial, these studies demonstrate the need for further investigation of the role of Cx45 in the maintenance or restoration of CBF after TBI.

We observed a small, temporary reduction in Cx43 mRNA expression early after injury (2 h), and no significant changes in Cx43 protein expression at 24 h post-injury, making it unlikely that Cx43 plays a significant long-term role in cerebral vascular dysfunction after TBI. However, a small acute decrease in gene expression may influence CBF in the first few hours after injury. In other studies, Cx43 has been reported to play a role after vascular injury. Using Cx43 knockout mice and the GJ inhibitor carbenoxolone, Song and colleagues (2009) found that blocking Cx43 GJs after systemic vascular injury minimizes neointimal proliferation. Thus, the therapeutic usefulness of targeting Cx43 requires further research.

Although no significant changes in Cx40 mRNA were detected, Cx40 protein was increased 24 h after injury. Cx40 mRNA was present in both smooth muscle and endothelial cells; Cx40 has been shown to predominate in the endothelial layer of the rat aorta (Bruzzone et al., 1993), being the most abundant Cx in this tissue (van Kempen and Jongsma, 1999). Studies in knockout mice indicate that Cx40 has an important role in vascular development and blood pressure regulation (Figueroa and Duling, 2009). Ablation of Cx40 produced hypertension associated with irregular vasomotion, and interfered with the regenerative component of conducted vasodilation (de Wit et al., 2003). Thus increased expression of Cx40 protein in cerebral arteries 24 h after TBI may improve coordination of vasomotor tone and conduction of vasodilation signals, thereby contributing to restoration of vessel function, and thus may be a protective response to injury and a possible treatment target.

Although we observed Cx37 mRNA expression in smooth muscle and endothelial cells, we found no effects of TBI on Cx37 mRNA, and we failed to detect Cx37 protein. The absence of Cx37 protein expression is consistent with the findings of Sokoya and associates (2006), who reported no Cx37 immunofluorescence in the endothelial cell layer of rat MCAs. Since we were unable to detect Cx37 protein, we have no verification of Cx37 protein expression in rodent cerebral arteries. Thus Cx37 may not have an important role in the cerebrovascular response to TBI.

Previous investigations demonstrated changes in gene expression after traumatic injury (Dash et al., 2004; Hayes et al., 1995; Hellmich et al., 2005,2008; Shimamura et al., 2004,2005). Mechanical injury (Morrison et al., 2000) or other types of trauma, including ischemia or seizures, can lead to disruption of calcium homeostasis that can produce alterations in gene expression (Bazan et al., 1995; West et al., 2001). Fluid percussion TBI altered the expression of immediate early genes secondary to random depolarization and large potassium efflux (Giza et al., 2002). Thus, ample evidence indicates that traumatic injury can alter gene expression, and although we did not specifically address the issue of model-dependency, it is likely that the results presented here are not model-dependent.

The use of LCM methods permitted the examination of the effects of TBI on Cx gene expression specifically in endothelial or smooth muscle cells, while RPA allowed for absolute, quantitative measures of mRNA levels (Shimamura et al., 2004). Vascular smooth muscle cells contain all four of the vascular Cxs. While only three of them, Cx37, Cx40, and Cx43, have previously been observed in endothelial cells, Cx45 protein expression has only been reported sparingly in the vascular endothelial layer early in development in mice (Haefliger et al., 2004). This is the first report of significant differences in Cx mRNA expression between vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells in cerebral arteries. Although the magnitude of the change in mRNA observed after TBI was small, small changes in mRNA can contribute to significant changes in functional outcomes, as in the case of enzymes that have catalytic activity (Clarke et al., 1984). For instance, a 20% change in mRNA for the serotonin 2A receptor corresponded with increased swimming behavior in the forced swim test (Sell et al., 2008), suggesting that modest changes in mRNA expression can have significant influences on functional outcomes.

For measures of Cx protein levels using Western blot analysis, whole-vessel homogenates were necessary to obtain sufficient protein for detection. The greater abundance of smooth muscle cells compared to endothelial cells in vascular tissue suggests that the protein detected in whole-tissue homogenates reflects primarily the contribution of smooth muscle cells.

Changes in Cx expression and GJ communication in the cerebral vasculature post-TBI may be beneficial, detrimental, or both. After injury, reactive oxygen species and other toxic metabolites accumulate in the cytoplasm of cerebral vascular cells; some of these may be small enough to pass through GJs to coupled healthy cells. This could be hazardous and protective at the same time, because it could increase diffusion of toxic metabolites to coupled cells and compromise their function (Lin et al., 1998), or instead, healthy surrounding cells could buffer those toxic substances (Blanc et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2003).

Our results indicating that fluid-percussion TBI is associated with changes in vascular Cx mRNA and protein expression support the idea that TBI impairs GJ coupling by altering the expression of specific Cxs in cerebral vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. However, it is unlikely that the changes observed here would contribute to cerebrovascular changes immediately or acutely after injury. Since gene and protein expression changes can take hours to days, it is more likely that these observations point to long-term physiological effects on cerebral vascular health. Furthermore, other mechanisms may be more relevant for short-term effects. For example, TBI-induced Cx phosphorylation may trigger the internalization of Cxs (Laird, 2005), thereby inhibiting GJ communication without affecting gene or protein levels. Additionally, tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and cadherin contribute to GJ formation (Hesketh et al., 2009), suggesting that disruption of tight junctions by TBI may result in impaired GJ communication. Other evidence supports a role for reactive oxygen species. TBI increases superoxide production (Fabian et al., 1998; Kontos and Wei, 1986), and protein kinase C activation (Yang et al., 1993), and these phenomena are also associated with GJ uncoupling.

Thus the results presented here suggest that changes in Cx gene and protein expression after TBI contribute in part to GJ dysfunction in what is likely a complicated physiological response to brain injury involving many factors. This is a primary investigation of the mechanisms by which TBI disturbs GJ communication processes. Understanding these mechanisms is an avenue toward potential treatment for TBI by therapies designed to improve GJ coupling in the cerebrovasculature.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following for their expert assistance: Bridget Capra, Research Associate, animal preparation; Kristine Eidson, Research Associate, tissue processing; Rashmi Mueller, M.D., Assistant Professor, animal preparation, study design; Margaret Parsley, Assistant Laboratory Director, animal preparation, tissue collection; and Andrew Hall and Maria-Adelaide Micci, Ph.D., editorial assistance.

These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS19355 (D.S.D.), and the Moody Center for Traumatic Brain & Spinal Cord Injury Research/Mission Connect.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Armstead W.M. Kiessling J.W. Cines D.B. Higazi A.A. Glucagon protects against impaired NMDA-mediated cerebrovasodilation and cerebral autoregulation during hypotension after brain injury by activating cAMP protein kinase A and inhibiting upregulation of tPA. J. Neurotrauma. 2011;28:451–457. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead W.M. Role of endothelin-1 in age-dependent cerebrovascular hypotensive responses after brain injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;274:H1884–H1894. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan N.G. Rodriguez de Turco E.B. Allan G. Mediators of injury In Neurotrauma: intracellular signal transduction, gene expression. J. Neurotrauma. 1995;12:791–814. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc E.M. Bruce-Keller A.J. Mattson M.P. Astrocytic gap junctional communication decreases neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress-induced disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis and cell death. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:958–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70030958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouma G.J. Muizelaar J.P. Relationship between cardiac output and cerebral blood flow in patients with intact and with impaired autoregulation. J. Neurosurg. 1990;73:368–374. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.3.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R. Haefliger J.A. Gimlich R.L. Paul D.L. Connexin40, a component of gap junctions in vascular endothelium, is restricted in its ability to interact with other connexins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993;4:7–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C.F. Fogelman A.M. Edwards P.A. Diurnal rhythm of rat liver mRNAs encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:10439–10447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash P.K. Kobori N. Moore A.N. A molecular description of brain trauma pathophysiology using microarray technology: an overview. Neurochem. Res. 2004;29:1275–1286. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000023614.30084.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit C. Roos F. Bolz S.S. Pohl U. Lack of vascular connexin 40 is associated with hypertension and irregular arteriolar vasomotion. Physiol. Genom. 2003;13:169–177. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt D.S. Hawkins B.E. Zeng Y. Prough D.S. Penicillamine and superoxide dismutase improve vascular gap junction communication after injury. Anesthesiology. 2009:A785. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Taylor C.L. Whitley J.M. Deal D.D. Vines S.M. Regional cerebrovascular responses to progressive hypotension after traumatic brain injury in cats. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:H1276–H1284. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Traumatic cerebral vascular injury: the effects of concussive brain injury on the cerebral vasculature. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:795–825. doi: 10.1089/089771503322385755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C.E. Lyeth B.G. Povlishock J.T. Findling R.L. Hamm R.J. Marmarou A. Young H.F. Hayes R.L. A fluid percussion model of experimental brain injury in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 1987;67:110–119. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.1.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelborghs K. Haseldonckx M. Van Reempts J. Van Rossem K. Wouters L. Borgers M. Verlooy J. Impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in an experimental model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2000;17:667–677. doi: 10.1089/089771500415418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian R.H. DeWitt D.S. Kent T.A. The 21-aminosteroid U-74389G reduces cerebral superoxide anion concentration following fluid percussion injury of the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:433–440. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa X.F. Duling B.R. Gap junctions in the control of vascular function. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2009;11:251–266. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giza C.C. Prins M.L. Hovda D.A. Herschman H.R. Feldman J.D. Genes preferentially induced by depolarization after concussive brain injury: Effects of age and injury severity. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:387–402. doi: 10.1089/08977150252932352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding E.M. Robertson C.S. Bryan R.M. The consequences of traumatic brain injury on cerebral blood flow and autoregulation: a review. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 1999;21:299–332. doi: 10.3109/10641969909068668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbenkian S. Uddman R. Edvinsson L. Neuronal messengers in the human cerebral circulation. Peptides. 2001;22:995–1007. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefliger J.A. Nicod P. Meda P. Contribution of connexins to the function of the vascular wall. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;62:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B. Zeng Y. Prough D.S. DeWitt D.S. Penicillamine and superoxide dismutase improve vascular gap junction communication after injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:A5. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R.L. Yang K. Raghupathi R. McIntosh T.K. Changes in gene expression following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 1995;12:779–790. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward N.M. Immonen R. Tuunanen P.I. Ndode-Ekane X.E. Gröhn O. Pitkänen A. Association of chronic vascular changes with functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:2203–2219. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward N.M. Tuunanen P.I. Immonen R. Ndode-Ekane X.E. Pitkänen A. Gröhn O. Magnetic resonance imaging of regional hemodynamic and cerebrovascular recovery after lateral fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:166–177. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich H.L. Eidson K.A. Capra B.A. Garcia J.M. Boone D.R. Hawkins B.E. Uchida T. DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Injured Fluoro-Jade-positive hippocampal neurons contain high levels of zinc after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2007;1127:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich H.L. Eidson K. Cowart J. Crookshanks J. Boone D.K. Shah S. Uchida T. DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Chelation of neurotoxic zinc levels does not improve neurobehavioral outcome after traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;440:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich H.L. Garcia J.M. Shimamura M. Shah S.A. Avila M.A. Uchida T. Parsley M.A. Capra B.A. Eidson K.A. Kennedy D.R. Winston J.H. DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic hypotension suppress neuroprotective gene expression in injured hippocampal neurons. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:806–814. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh G.G. Van Eyk J.E. Tomaselli G.F. Mechanisms of gap junction traffic in health and disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2009;54:263–272. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181ba0811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek P.M. Hendrich K.S. Dixon C.E. Schiding J.K. Williams D.S. Ho C. Cerebral blood flow at one year after controlled cortical impact in rats: Assessment by magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:129–137. doi: 10.1089/089771502760341947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos H.A. Wei E.P. Superoxide production in experimental brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 1986;64:803–807. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.5.0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger O. Plum A. Kim J.S. Winterhager E. Maxeiner S. Hallas G. Kirchhoff S. Traub O. Lamers W.H. Willecke K. Defective vascular development in connexin 45-deficient mice. Development. 2000;127:4179–4193. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagaud G. Gaudreault N. Moore E.D. Van Breemen C. Laher I. Pressure-dependent myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries occurs independently of voltage-dependent activation. Am. J. Physiol. 2002a;283:H2187–H2195. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagaud G. Karicheti V. Knot H.J. Christ G.J. Laher I. Inhibitors of gap junctions attenuate myogenic tone in cerebral arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 2002b;283:H2177–H2186. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00605.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird D.W. Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction internalization and degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1711:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewelt W. Jenkins L.W. Miller J.D. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow after experimental fluid percussion injury of the brain. J. Neurosurg. 1980;53:500–511. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.4.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.H. Weigel H. Cotrina M.L. Liu S. Bueno E. Hansen A.J. Hansen T.W. Goldman S. Nedergaard M. Gap-junction-mediated propagation and amplification of cell injury. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:494–500. doi: 10.1038/2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.H. Yang J. Liu S. Takano T. Wang X. Gao Q. Willecke K. Nedergaard M. Connexin mediates gap junction-independent resistance to cellular injury. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:430–441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00430.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Simard J.M. Connexin45 gap junction channels in rat cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;281:H1890–H1898. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein W.R. Junctional intercellular communication: the cell-to-cell membrane channel. Physiol. Rev. 1981;61:829–913. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison B. Eberwine J.H. Meaney D.F. McIntosh T.K. Traumatic injury induces differential expression of cell death genes in organotypic brain slice cultures determined by complementary DNA array hybridization. Neuroscience. 2000;96:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawashiro H. Shima K. Chigasaki H. Immediate cerebrovascular responses to closed head injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 1995;12:189–197. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi A. Nawashiro H. Otani N. Ooigawa H. Toyooka T. Shima K. Temporal and spatial profile of phosphorylated connexin43 after traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1255–1263. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal S.S. Duling B.R. Conduction of vasomotor responses in arterioles: a role for cell-to-cell coupling? Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:H838–H845. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.3.H838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S.L. Craft R.M. Seitz P.K. Stutz S.J. Cunningham K.A. Thomas M.L. Estradiol-sertraline synergy in ovariectomized rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S.L. Zeng Y.P. Mathew B.P. Prough D.S. DeWitt D.S. Estradiol increases gap junction communication and vasodilation following injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:A5. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura M. Garcia J.M. Prough D.S. Dewitt D.S. Uchida T. Shah S.A. Avila M.A. Hellmich H.L. Analysis of long-term gene expression in neurons of the hippocampal subfields following traumatic brain injury in rats. Neuroscience. 2005;131:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura M. Garcia J.M. Prough D.S. Hellmich H.L. Laser capture microdissection and analysis of amplified antisense RNA from distinct cell populations of the young and aged rat brain: effect of traumatic brain injury on hippocampal gene expression. Mol. Brain Res. 2004;17:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoya E.M. Burns A.R. Setiawan C.T. Coleman H.A. Parkington H.C. Tare M. Evidence for the involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in EDHF-mediated relaxation in the rat middle cerebral artery. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H385–H393. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan J.L. Lampe P.D. Connexin43 phosphorylation: structural changes and biological effects. Biochem. J. 2009;419:261–272. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. Yu X. Cui X. Zhu G. Zhao G. Chen J. Huang L. Blockade of connexin 43 hemichannels reduces neointima formation after vascular injury by inhibiting proliferation and phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2009;234:1192–1200. doi: 10.3181/0902-RM-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujiie H. Chaytor A.T. Bakker L.M. Griffith T.M. Essential role of gap junctions in NO- and prostanoid-independent relaxations evoked by acetylcholine in rabbit intracerebral arteries. Stroke. 2003;34:544–550. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000054158.72610.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen M.J. Jongsma H.J. Distribution of connexin37, connexin40 and connexin43 in the aorta and coronary artery of several mammals. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1999;112:479–486. doi: 10.1007/s004180050432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A.E. Chen W.G. Dalva M.B. Dolmetsch R.E. Kornhauser J.M. Shaywitz A.J. Takasu M.A. Tao X. Greenberg M.E. Calcium regulation of neuronal gene expression. PNAS. 2001;98:11024–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K. Taft W.C. Dixon C.E. Todaro C.A. Yu R.K. Hayes R.L. Alterations of protein kinase C in rat hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1993;10:287–295. doi: 10.1089/neu.1993.10.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.-X. Prough D.S. Vergara L.A. DeWitt D.S. Impaired gap junction communication after rapid stretch injury in vascular smooth muscle cells. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:A796. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.-X. Wang Y. Prough D.S. DeWitt D.S. The peroxynitrite scavenger, FeTPPS, reduces endothelial cell injury after stretch-induced trauma in vitro. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1074. [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.-Y. Prough D.S. Mathew B.P. Parsley M.O. DeWitt D.S. Penicillamine improves gap junction communication between smooth muscle cells in middle cerebral arteries after moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1181. [Google Scholar]