Abstract

Purpose

Aim of this study was to determine if BORIS (Brother of the Regulator Of Imprinted Sites) is a regulator of MAGEA2, 3 and 4 genes in lung cancer.

Experimental Design

Changes in expression of MAGEA genes upon BORIS induction/knockdown were studied. Recruitment of BORIS and changes in histone modifications at their promoters upon BORIS induction were analyzed. Luciferase assays were used to study their activation by BORIS. Changes in methylation at these promoters upon BORIS induction were evaluated.

Results

Alteration of BORIS expression by knockdown/induction directly correlated with expression of MAGEA genes. BORIS was enriched at their promoters in H1299 cells, which show high expression of these cancer testis antigens (CTAs), compared to NHBE cells which show low expression of the target CTAs. BORIS induction in A549 cells resulted in increased amounts of BORIS and activating histone modifications at their promoters along with a corresponding increase in their expression. Similarly, BORIS binding at these promoters in H1299 correlates with enrichment of activating modifications while absence of BORIS binding in NHBE is associated with enrichment of repressive marks. BORIS induction of MAGEA3 was associated with promoter demethylation, but no methylation changes were noted with activation of MAGEA2 and MAGEA4.

Conclusions

These data suggest that BORIS positively regulates these CTAs by binding and inducing a shift to a more open chromatin conformation with promoter demethylation for MAGEA3 or independent of promoter demethylation in case of MAGEA2 and A4 and may be a key effector involved in their derepression in lung cancer.

Keywords: BORIS, MAGEA, promoter binding, transcriptional activation, methylation

Introduction

Genomes of tumors are frequently characterized by alterations in the DNA methylation patterns (1–3). Hyper- and hypo-methylation of individual gene promoters (4–10) as well as global hypomethylation are commonly found in a variety of tumors. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes leads to their inactivation while demethylation may cause activation of proto-oncogenes. One class of genes that is upregulated in many types of human tumors by promoter hypomethylation is the cancer testis antigens (CTAs), so named because they are expressed only in male germ cells and are also aberrantly up-regulated in a variety of cancers including lung and melanoma (11–14). The frequency of expression of the CTAs is variable in different tumor types and has been found to correlate with tumor grade. Melanomas, lung cancers and ovarian cancers have the highest frequency of CTA expression while leukemia, lymphomas, renal, colon and pancreatic cancers have a lower frequency of CTA expression. An expression array study performed in lung cancer cell lines showed that 30% of the overexpressed genes (6 out of 20) were CTAs (5 MAGEA and NY-ESO-1) (15). The results were validated by immunohistochemical testing for protein using a tissue microarray containing 187 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) clinical samples. Derepression of these genes in cultured cells after treatment with DNA methyl-transferase inhibitors like 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine shows that demethylation is a key factor governing the regulation of these genes (16–19). Using an integrative epigenetic screening approach, we have previously shown that CTAs are upregulated in NSCLC and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) by promoter hypomethylation (18, 19).

Although it is now well accepted that CTAs are epigenetically controlled, the regulatory mechanisms of these genes remain unclear. The transcription factor BORIS has emerged as a plausible candidate for the role of a dominant regulator of these genes. BORIS is a transcription factor that is paralogous to the well characterized, highly conserved, multivalent 11 Zn-finger factor CTCF (20, 21). The combinatorial use of its 11 Zn fingers allows CTCF to bind to distinct DNA sequences and makes it functionally versatile (22, 23). It functions as a transcriptional regulator and forms methylation dependent insulators that regulate genomic imprinting and X-chromosome inactivation (23). BORIS is the paralogue of CTCF with an identical 11-Zn finger domain but distinct N- and C- termini. It plays a crucial role in spermatogenesis by regulating the expression of testis-specific form of CST, a gene that is essential for spermatogenesis (24). Thus far, two reports have suggested a direct role for BORIS in the regulation of the CTA gene expression. Vatolin et al. have shown that overexpression of BORIS in normal cells leads to MAGEA1 promoter demethylation resulting in derepression of MAGEA1 expression (25). Also, reciprocal binding of CTCF and BORIS to the NY-ESO-1 promoter in lung cancer cells regulates the expression of this CTA (26). Binding of CTCF is associated with repression while binding of BORIS is associated with derepression of NY-ESO-1 expression. In two studies we have shown a correlation between the expression of CTAs and BORIS in NSCLC and HNSCC, suggesting a role for BORIS in the epigenetic derepression of this class of genes in human cancers (18, 19). The aim of this study was to determine if BORIS is a regulator of MAGE A2, 3 and 4 genes in lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, Plasmids and Transfections

Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial cells (NHBE) were obtained from Lonza (Switzerland) and grown according to manufacturer’s instructions. Lung cancer cell lines H1299 and A549 were obtained from American Type Cell Culture (ATCC). The lung cancer cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Small-hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmids for BORIS knockdown were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). H1299 cells were transiently transfected with 4 μg shRNA plasmid carrying BORIS specific shRNA cassette or the plasmid carrying a non-effective scrambled shRNA cassette using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). They were harvested in QIAzol (Qiagen, Valencia CA) for total RNA extraction 48 hours post-transfection. For ectopic BORIS expression, BORIS expression plasmid (pBIG2i-BORIS) and the control empty vector were used (19, 25). A549 cells were transfected with 1 μg of the plasmids using fugene HD (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Twenty-four hours post- transfection, cells were induced with 0.125 μg/ml doxycycline and were allowed to grow for 48 hours before harvesting for RNA/DNA extraction. For ChIP analysis, cells were grown in 150 cm2 dishes and transfected with 16 μg of the BORIS expression plasmid or the control empty vector. They were then induced with doxycycline as described above and harvested for ChIP analysis.

RNA extraction and quantitative Reverse-Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using QIAzol and RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cells were harvested in QIAzol and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using qScript cDNA mix (Quanta Biosciences). Real-time PCR was performed using the Fast SYBR green master mix on the ABI 7900HT real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Primers used are listed in Table S1.

Chromatin-Immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

Exponentially growing H1299 and NHBE cells were used for ChIP assay. ChIP was performed using the Magna ChIP™ G Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. We used two different BORIS antibodies for this assay- commercially available antibody from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and an antibody kindly provided by Dr. Gius (27). Histone antibodies used are anti-rabbit trimethyl-H3K4, acetyl-H3K9/14 and trimethyl-H3K9 (Millipore). Non-specific rabbit IgG (Millipore) was used as control. A549 cells transfected with BORIS expression plasmid or the control empty vector were also used for this assay.

Construction of luciferase constructs

Promoter fragments were synthesized and cloned into the pUC 57 vector by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). The fragments were then sub-cloned into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). The fragments cloned were as follows: MAGEA2-1000 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site upto the middle of the fourth exon, MAGEA3- 1000 base pairs upstream upto the end of the second exon and MAGEA4- 1000 base pairs upstream to the middle of the first intron. MAGEA2 and MAGEA4 promoter fragments were cloned between KpnI and HindIII restriction sites. The MAGEA3 promoter fragment was cloned between SmaI and HindIII restriction sites. Sequences of the promoter regions were confirmed by sequencing.

Luciferase assay

H1299 cells were transfected with BORIS shRNA plasmid or non-specific scramble shRNA plasmid using lipofectamine 2000 reagent. At 48 hours after transfection, cells were transfected again with either specific promoter-luciferase constructs (described above) or pGL3-basic vector (Promega) and pRL-TK (Promega) at a ratio of 50:1. pRL-TK served as an internal control. Twenty-four hours after transfection with the promoter-luciferase constructs, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with 1X PLB (Passive lysis buffer) provided in the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking. The lysates were collected and dual-luciferase activity measured using Glomax 96 microplate luminometer (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 20 μl of the lysates were mixed with luciferase assay reagent (LARII) and firefly luminescence measured. Following measurement of the firefly luciferase activity, the reactions were stopped using the stop and glo buffer and the renilla luciferase activity was measured. The firefly luciferase activity that represented the activity of the cloned promoter region was normalized to the renilla luciferase activity. A549 cells transfected with BORIS expression plasmid or the empty vector were also used for this assay. Cells were transfected with the expression or the control plasmid and induced with 0.125 μg/ml doxycycline 24 hours after transfection. Forty-eight hours after induction with doxycycline, the cells were transfected with promoter luciferase constructs or pGL3- basic vector and pRL-TK as described above. At 24 hours after this second transfection, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity recorded.

DNA extraction, bisulfite sequencing and quantitative methylation-specific PCR (QMSP)

DNA extraction, bisulfite sequencing and QMSP were performed as described before (4, 18). For QMSP, primers were designed to specifically include CpGs that showed changes in methylation seen by bisulfite sequencing. Real-time PCR was performed using the Fast SYBR green master mix on the ABI 7900HT real-time PCR machine with normalization to beta-actin primers that do not contain CpGs in the sequence for quantitation. Primers used are listed in Table S1.

Results

BORIS and CTAs are derepressed in lung cancer cell lines compared to normal lung cells

We used qRT-PCR to determine the expression levels of BORIS, MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 in lung cancer cell lines H1299 and A549, and in a normal lung cell line, NHBE. Expression levels of these genes in the three cell lines are shown in Table 1. H1299 cells showed the highest levels of expression of BORIS as well as all the CT genes tested. NHBE cells showed very low or no expression of these genes. Based on these expression profiles we selected H1299 for studying the effects of BORIS knockdown on the target genes. A549 cells showed very low levels of BORIS and the target CTAs and were used for inducing BORIS expression to look at the effect of its overexpression on target CTAs.

Table 1.

Expression of BORIS, MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 in H1299, A549 and NHBE cells. qRT-PCR was done to measure their expression. Expression levels (ddCt) are relative to the levels in H1299. H1299 shows the highest expression levels of these genes while A549 and NHBE show very low or no expression.

| BORIS | MAGEA2 | MAGEA3 | MAGEA4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1299 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A549 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 0.2 | 0 |

| NHBE | 0.34 | 0.0006 | 0.0001 | 0 |

BORIS derepresses CTAs in lung cancer cell lines

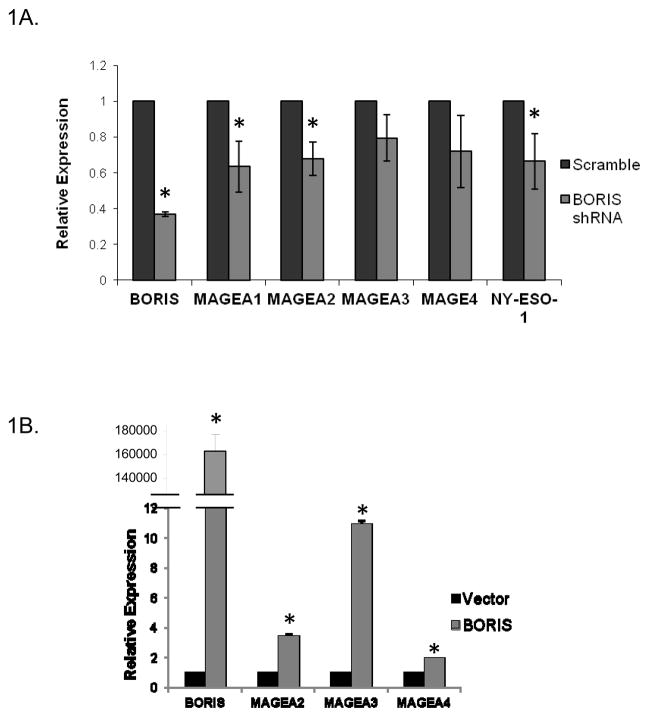

To evaluate the effect of BORIS on the expression of the selected targets, we knocked down the expression of BORIS in H1299 cells using a plasmid carrying a BORIS-specific shRNA cassette. H1299 cells were transiently transfected with the BORIS shRNA plasmid and control plasmid carrying a scramble shRNA sequence. At 48 hours after transfection, we measured the changes in the mRNA levels of BORIS and the target CTAs. BORIS mRNA levels were knocked down to approximately 40% compared to the control plasmid transfected cells as measured by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1A). Upon reduction of BORIS expression, the expression of all the selected targets as well as two control CTAs, MAGEA1 and NY-ESO-1, were reduced by 20–40% compared to the control cells (Fig. 1A). We then wanted to see if aberrant BORIS expression in a low-expressing cell line would alter the expression profile of the target CTAs. We, therefore, transiently induced BORIS expression in the A549 cell line, which shows low levels of BORIS and other CTAs. Following transient transfection of the cells with BORIS expression plasmid and induction with doxycycline, we measured the mRNA levels of BORIS and the CTAs. Cells transfected with the empty vector were used as control. There was significant upregulation of BORIS mRNA in the cells transfected with the BORIS expression plasmid (Fig. 1B). We also saw a marked increase in the levels of the MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 expression in these cells (Fig. 1B). These results showed that altering the levels of BORIS expression in cells positively correlates with the levels of the target CTAs suggesting a role for BORIS in the activation of these genes. We could not validate BORIS protein levels due to unavailability of acceptable antibody for western blot.

Figure 1.

Effects of altering the levels of BORIS on expression of the target CTAs. A, Expression of BORIS and CTAs after knocking down BORIS expression in H1299 cells is shown (*, p < 0.05). BORIS specific shRNA was used for knocking down BORIS expression. shRNA containing a scramble sequence was used as control. Expression was measured 48 hours after treatment with the shRNAs. The reduction in MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 expression showed borderline significance by t-test which may be attributed to residual amounts of BORIS (~ 40%) left behind after treatment with shRNA. Only significant p-values are shown. For those bar graphs where the p-values are not significant, (p-value > 0.05), we have not reported these values. B, Expression of BORIS and CTAs after transient transfection of A549 cells with BORIS expression plasmid and control empty vector is shown (*, p < 0.001). Cells were induced with 0.125 μg/ml doxycycline 24 hours after transfection for 48 hrs. All expression measurements in A and B were made using qRT-PCR.

BORIS is recruited to the promoters of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 in vivo

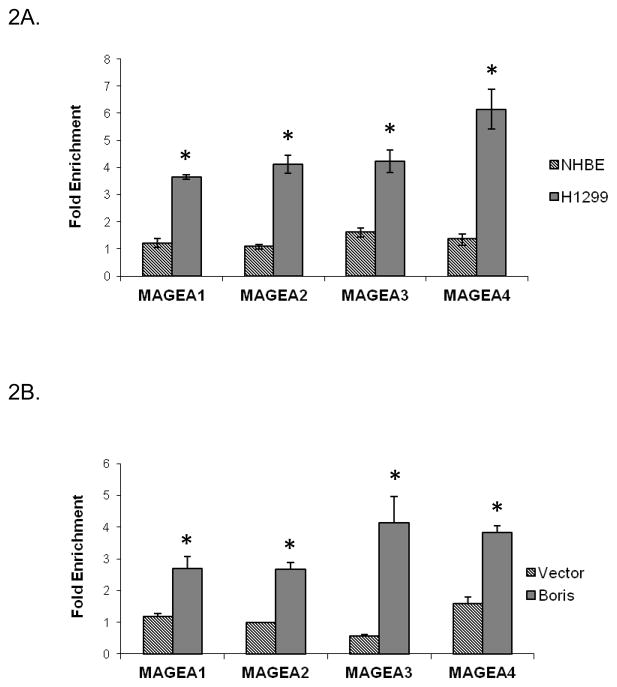

In light of the finding that BORIS regulates the levels of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 gene transcription, we wanted to investigate if this was a direct effect of BORIS binding to their promoters. Therefore, we looked for binding of BORIS at the promoters of these genes in H1299 and NHBE cells using chromatin-immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP). With prior knowledge of BORIS binding to the promoter of MAGEA1 as shown by Vatolin et. al. (25), we were able to delineate the homologous promoter regions of MAGEA2, A3 and A4 to be tested for BORIS binding. The promoter regions tested for BORIS binding are shown in Fig. S1. We used two different BORIS antibodies for this assay (a commercially available antibody from Abcam and an antibody provided by Dr. Gius (27)) and obtained similar results using both antibodies. We found that BORIS was enriched at the promoter regions of all the three MAGEA targets in the H1299 cells (Fig. 2A). BORIS was also enriched at the control promoter, MAGEA1, in H1299 cells (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, no BORIS binding was seen at the target or the control gene promoters in the NHBE cells (Fig. 2A). This suggested that BORIS binding to the promoters of the target genes is associated with their derepression in H1299 cells. These genes remain repressed in NHBE cells in absence of BORIS binding.

Figure 2.

In vivo occupancy of the target gene promoters by BORIS as analyzed by ChIP. BORIS binding at the promoter regions in A, exponentially growing H1299 and NHBE cells (*, p < 0.02) and B, in control A549 cells and cells induced to express exogenous BORIS (*, p < 0.05) is shown. A549 cells were transiently transfected with BORIS expression plasmid and control empty vector. Cells were induced with 0.125 μg/ml doxycycline 24 hours after transfection for 48 hrs. They were then crosslinked for ChIP analysis as described in materials and methods. Commercially available BORIS antibody from Abcam and non-specific rabbit IgG (negative control) were used for immunoprecipitation. Chromatin pulled down by the BORIS antibody and non-specific IgG was purified and analyzed by quantitative-PCR. Fold enrichment is relative to IgG binding.

As shown in figure 1B, BORIS induction in A549 cells causes a marked increase in the expression levels of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4. We wanted to see if the increased expression of the target genes was accompanied by an increased BORIS binding at their promoters. Therefore, we determined the binding of BORIS at their promoters following induction of BORIS as described above. Increased levels of BORIS and increased expression of the target CTAs coincided with increased occupancy of the promoters by BORIS (Fig. 2B). No BORIS binding was seen at the promoters in the empty vector transfected cells (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that BORIS activates it targets by binding to their promoters.

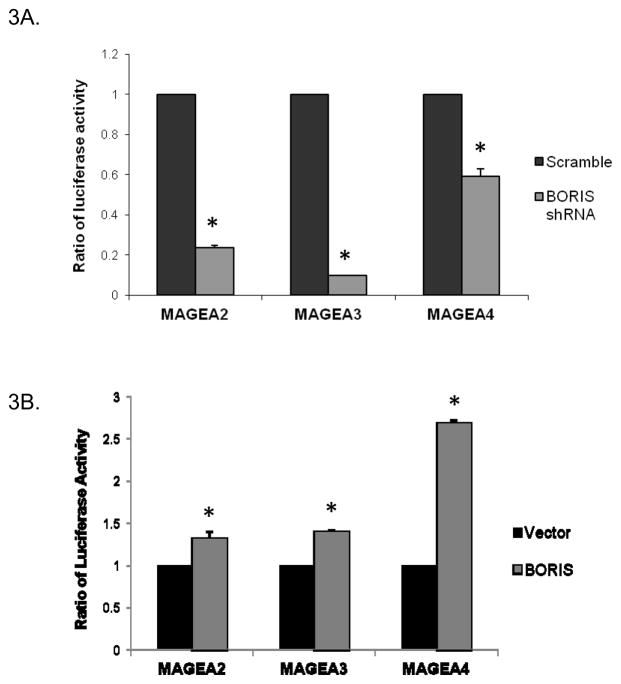

BORIS activates the promoters of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4

Confirmation of BORIS recruitment at the three target MAGEA promoters as well as regulation of these genes by BORIS led us to investigate the regulation of their promoters by BORIS. We performed luciferase reporter assays to investigate the regulation of the promoters by BORIS in lung cancer and normal cells. We cloned the promoters of the three genes upstream of the luciferase gene in the promoter-less plasmid, pGL3-basic. Using shRNA, we knocked down the levels of BORIS expression in H1299 cells. To ensure BORIS levels were knocked down before we measured the promoter activity, we treated the cells with shRNA for 48 hours before transfecting the promoter luciferase constructs. Luciferase activity was measured 24 hours after transfection with the promoter constructs. Cells transfected with BORIS shRNA showed a dramatic decrease in the luciferase activity compared to the cells treated with non-specific scrambled shRNA (Fig. 3A). We also measured the promoter activity in A549 cells following induction of BORIS expression. BORIS induction in A549 cells markedly increased the activity of all three promoters tested (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that BORIS binds to and activates the promoters of the three MAGEA genes tested.

Figure 3.

Effect of BORIS on promoter activity as measured by luciferase reporter assay. Promoter activities of MAGEA2, A3 and A4 were measured A, after knocking down BORIS expression in H1299 cells (*, p < 0.0005) and B, upon induction of BORIS expression in A549 cells (*, p < 0.004). Firefly luciferase activity, that represents the promoter activity, was normalized to renilla luciferase activity.

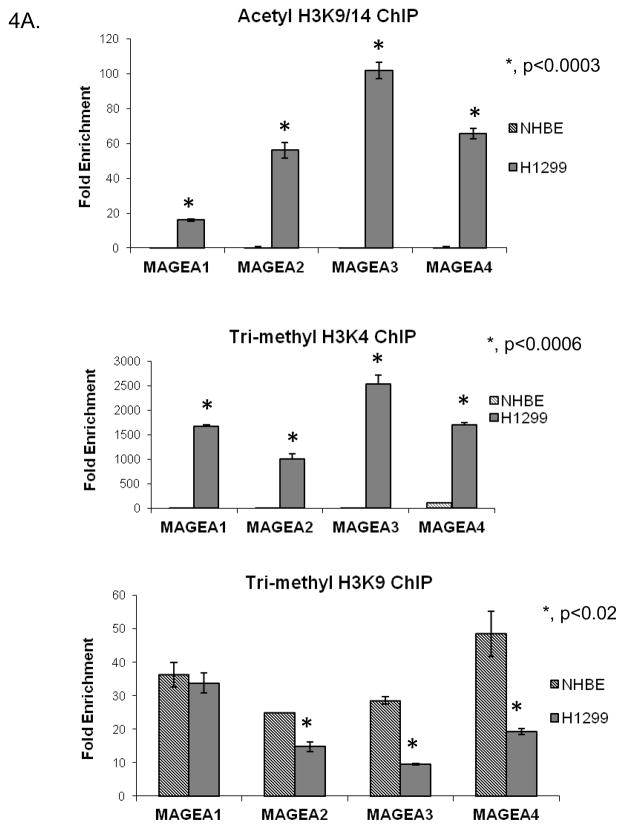

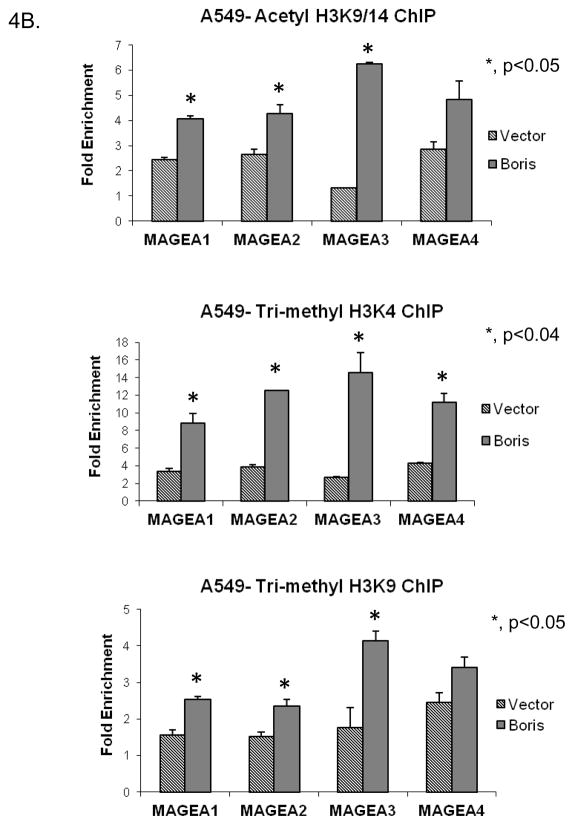

BORIS recruitment at the promoters coincides with the enrichment of activating histone modifications

In the past decade, a new concept called the “histone code” hypothesis has emerged that explains the functional consequences of the variable types of covalent modifications present on the core histone tails. According to this hypothesis, the types of covalent modifications associated with histone tails dictate the recruitment of specific factors that in turn define the formation of open or closed chromatin structures (28–35). BORIS has been shown to change the histone methylation status of the bag-1 gene from a non-permissive to permissive status (27). BORIS also helps in the recruitment of histone (H3K4) methyl transferase, SET1A, onto the promoters of myc and BRCA1 to promote a permissive histone modification status (36). We wanted to determine if BORIS occupancy of the MAGEA promoters was associated with specific histone tail modifications. Therefore, we used ChIP to determine the type of histone modifications enriched at the promoters of these genes in the presence or absence of BORIS. We tested the presence of two modifications that are enriched in transcriptionally active chromatin regions, namely acetylated histone H3 lysine 9/14 (H3K9/14) and tri-methylated histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) and one that is present in transcriptionally silent regions, namely tri-methylated histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9). In H1299 cells, the presence of BORIS at the promoter regions coincided with the presence of the two activating modifications (Fig. 4A). In NHBE cells, on the other hand, the absence of BORIS coincided with the presence of the silencing modification (Fig. 4A). We then checked whether changing levels of BORIS in cells would alter the levels of different histone modifications at the target gene promoters. We induced the expression of BORIS in A549 cells and determined the levels of different histone modifications at the target genes promoters. Cells transfected with the empty vector were used as control. Induction of BORIS resulted in increased levels of BORIS occupancy at the target promoters as shown in Fig. 2B. This increased BORIS presence at the promoters, resulted in increased presence of the activating histone modifications, acetylated H3K9/14 and tri-methylated H3K4, at the promoters compared to the control cells (Fig. 4B). This suggested that presence of BORIS at the promoters induces a change in the histone modification pattern more conducive to active gene transcription. Surprisingly, levels of the repressive mark tri-methyl H3K9 also increased at these promoters in presence of BORIS (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Presence of three core histone modifications namely acetyl H3K9/14, trimethyl H3K4 and trimethyl H3K9, at target promoters as evaluated using ChIP. This analysis was done in A, exponentially growing H1299 and NHBE cells and B, Control A549 cells and A549 cells induced to express exogenous BORIS. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR. Rabbit IgG was used as negative control. Fold enrichment is relative to IgG binding. Only significant p-values are shown.

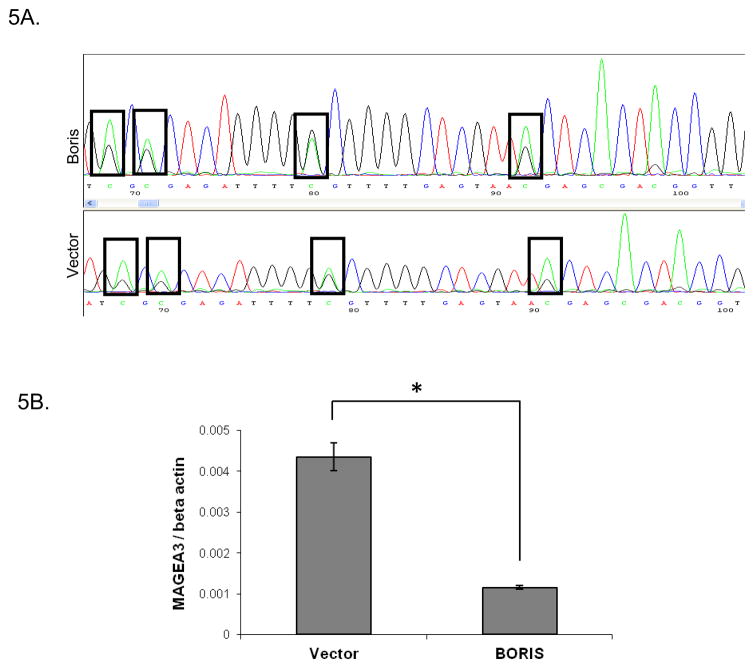

BORIS expression is associated with demethylation of MAGEA3 promoter

It has been reported previously that aberrant BORIS expression in NHDF cells (Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts) causes demethylation of the MAGEA1 promoter (25). We performed bisulfite sequencing and QMSP to assess the changes in methylation status of MAGEA2, A3 and A4 promoters associated with aberrant BORIS expression. We induced the expression of BORIS in A549 cells and analyzed the methylation status of the MAGEA2, A3 and A4 promoters using bisulfite sequencing. MAGEA3 promoter showed reduced methylation of 4 out of 15 CpG dinucleotides analyzed, as judged by a reduced cytosine to thymine nucleotide ratio, upon overexpression of BORIS (Fig. 5A). We did not see any changes in the methylation of CpG dinucleotides in the MAGEA2 and MAGEA4 promoters under similar conditions of BORIS overexpression (data not shown). The promoter region of MAGEA3 analyzed by bisulfite sequencing is shown in Fig. S2. We next performed QMSP to confirm the changes in methylation seen in the MAGEA3 promoter. We saw a significant reduction in the methylation of the MAGEA3 promoter upon overexpression of BORIS (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that BORIS may regulate the expression of MAGEA3 by promoting demethylation of its promoter. However, the lack of any changes in the methylation of MAGEA2 and MAGEA4 promoter regions upon BORIS overexpression may indicate an alternative mechanism by which BORIS regulates their expression.

Figure 5.

Effect of aberrant expression of BORIS on promoter methylation. MAGEA3 promoter methylation assessed by A, bisulfite sequencing and B, QMSP, after transient transfection of A549 cells with BORIS expression plasmid and control empty vector is shown (*, p = 8.7 × 10−5). Cells were induced with 0.125μg/ml doxycycline 24 hours after transfection for 48 hrs. Values are normalized to beta-actin. In A green peaks represent C and black peaks represent T.

Discussion

CTAs are proteins that are normally expressed only in the male germ cells. These proteins are not expressed in other normal somatic tissues but are aberrantly upregulated in a variety of cancers like lung and melanoma. The expression of CT genes is known to be regulated epigenetically by promoter methylation. Global hypomethylation, which is a hallmark of many cancers, as well as promoter specific demethylation are the key factors involved in the derepression of these genes in a wide variety of cancers, and we have shown that CTAs are upregulated in NSCLC and HNSCC by promoter hypomethylation. Although it is well known that methylation plays a role in the regulation of these genes, the mechanism of their regulatory pathway remains unknown. Whether these highly homologous genes that show coordinated expression patterns (37, 38) are under the control of a common pathway is still an open question. Two recent reports have suggested a role for BORIS in the regulation of the CTAs, MAGEA1 and NY-ESO-1. With the knowledge that BORIS regulates the transcription of two CTAs and the premise that CTAs may have a common regulatory pathway, we investigated if BORIS also regulates the expression of three other MAGEA genes- MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4. Our study revealed a direct correlation between BORIS induction and expression of the three MAGEA genes. Interestingly, we also saw that increased amounts of BORIS resulted in increased recruitment of BORIS at the target promoters. This clearly suggested that BORIS is an effector in the upregulation of these genes and does so by directly binding to their promoters. Promoter activity assays further validated the role of BORIS in activating these promoters. Thus, these data suggest that BORIS is a significant regulator of a broad range of CTAs.

Our data indicate that BORIS is involved in the activation of the CTAs tested. However, the underlying mechanism/s by which BORIS activates these CTAs still remains incompletely defined. Our study shows that binding of BORIS at the CT gene promoters results in enrichment of two histone modifications at these promoters-acetylated H3K9/14 and methylated H3K4- that are known to play a role in the formation of open chromatin conformation. According to the histone code hypothesis, combinations of core histone modifications define binding sites for different types of proteins that in turn dictate the formation of open or closed chromatin conformation. This suggests that BORIS binding may help in shifting the chromatin conformation from a closed to a more open state. The kind of transcriptional activators that BORIS binding helps in recruiting to the promoters would be of significant interest, and may help further define the role of BORIS in transcriptional activation. Another mechanism by which BORIS may be speculated to regulate the expression of CTAs is via promoter demethylation. It has been reported in the literature that BORIS overexpression is associated with the demethylation of at least one CTA promoter, MAGEA1 (25). In this study, we have shown that BORIS overexpression induces demethylation of another CTA promoter, MAGEA3, which further supports the role for BORIS as a demethylation promoting factor. However, the lack of change in promoter methylation of the other two CTAs studied, (MAGEA2 and A4) indicates the possibility of transcriptional regulation independent of promoter methylation changes. For example, NY-ESO-1 is derepressed in lung cancer cells by BORIS mediated recruitment of a transcription factor Sp1 onto its promoter (39), and derepression of this CTA does not coincide with the demethylation of its promoter (26, 39). These observations further support our results that BORIS regulates CTA gene expression through methylation dependent and independent mechanisms. A recent report that investigated the role of BORIS in the regulation of Rb2/p130 gene transcription has shown that BORIS binding triggers changes in the local chromatin organization with respect to nucleosome positioning thus causing altered Rb2/p130 expression (40). Evaluating the effects of BORIS on nucleosome positioning at the MAGEA promoters would provide significant insight into its mechanism of action. Overall, our study suggests the regulation of CT genes by BORIS via epigenetic alterations. Although it is beyond the scope of this work, it would be of great interest to identify the downstream effectors in the putative BORIS transcription factor pathway that may be involved in the establishment of the epigenetic marks at these promoters.

As mentioned above, a noteworthy feature of CTA expression is that CTAs are often coordinately expressed in solid tumors. In a study where expression of 12 CTAs was evaluated in primary lung cancer tissues, it was seen that 62% of the samples showed expression of two or more CTAs (38). We have reported an epigenetic mechanism for the coordinated regulation of these genes in NSCLC (18). The regulation of CTAs by a common transcriptional mechanism may also explain the coordinated expression profile of the antigens.

Because of their exclusive expression in a wide variety of human cancers and their ability to elicit cellular and humoral immune responses, CTAs are promising targets for cancer immunotherapy (41–43). Two CTAs, MAGEA3 and NY-ESO-1, are being evaluated as targets for cancer vaccines in multiple clinical trials. If BORIS functions as a master activator of these genes, its induction might help in their upregulation that may in turn help the host in mounting an enhanced immune response. Finally, CTAs have been recently defined by us and other groups to have growth stimulatory properties (18, 19), and the involvement of a common regulatory control of CTA expression provides an opportunity for development of therapeutic agents for CTA expressing cancers.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Primers used for qRT-PCR, ChIP, bisulfite sequencing and QMSP.

Figure S1. Promoter regions of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 analyzed for BORIS binding by ChIP are shown. Transcription start sites are labeled +1. Exons are shown in uppercase. Promoters and introns are shown in lowercase. ChIP primers are underlined and shown in bold.

Figure S2. Promoter region of MAGEA3 analyzed by bisulfite sequencing and QMSP is shown. Transcription start site is labeled +1. Exon 1 is shown is in uppercase. Promoter region and intron are shown in lowercase. CpG dinucleotides are shaded and underlined.

Translational Relevance.

Cancer testis genes are potential oncogenes that are activated in a variety of cancers. These genes are known to be coordinately regulated and promoter hypomethylation plays a major role in their derepression in cancers. Here, we have shown that BORIS is a key common factor involved in the derepression of these genes in lung cancer cell lines. CTAs are promising targets for cancer immunotherapy because they are exclusively expressed in cancers and elicit cellular and humoral immune responses. If BORIS functions as a master activator of these genes, its induction might help in their upregulation that may in turn help the host in mounting an enhanced immune response. Also, CTAs have been shown to have growth stimulatory properties and the involvement of a common regulatory control of CTA expression provides an opportunity for development of therapeutic agents for CTA expressing cancers.

Acknowledgments

This paper/analysis is based on a web database application provided by Research Information Technology Systems (RITS) - https://www.rits.onc.jhmi.edu/

Grant support: NIH: NCI/NIDCR P50 CA096784

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Califano is the Director of Research of the Milton J. Dance Head and Neck Endowment. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Das PM, Singal R. DNA methylation and cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4632–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Momparler RL, Bovenzi V. DNA methylation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:145–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200005)183:2<145::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demokan S, Chang X, Chuang A, Mydlarz WK, Kaur J, Huang P, et al. KIF1A and EDNRB are differentially methylated in primary HNSCC and salivary rinses. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2351–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brait M, Begum S, Carvalho AL, Dasgupta S, Vettore AL, Czerniak B, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation of multiple genes during pathogenesis of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2786–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrow KL, Park HL, Hoque MO, Kim MS, Liu J, Argani P, et al. Pharmacologic unmasking of epigenetically silenced genes in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1184–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation of ras oncogenes in primary human cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;111:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(83)80115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanada M, Delia D, Aiello A, Stadtmauer E, Reed JC. bcl-2 gene hypomethylation and high-level expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1993;82:1820–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watt PM, Kumar R, Kees UR. Promoter demethylation accompanies reactivation of the HOX11 proto-oncogene in leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:371–7. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1050>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun W, Liu Y, Glazer CA, Shao C, Bhan S, Demokan S, et al. TKTL1 is activated by promoter hypomethylation and contributes to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma carcinogenesis through increased aerobic glycolysis and HIF1alpha stabilization. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:857–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zendman AJ, Ruiter DJ, Van Muijen GN. Cancer/testis-associated genes: identification, expression profile, and putative function. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:272–88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:615–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Smet C, Lurquin C, Lethe B, Martelange V, Boon T. DNA methylation is the primary silencing mechanism for a set of germ line- and tumor-specific genes with a CpG-rich promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7327–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koslowski M, Bell C, Seitz G, Lehr HA, Roemer K, Muntefering H, et al. Frequent nonrandom activation of germ-line genes in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5988–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugita M, Geraci M, Gao B, Powell RL, Hirsch FR, Johnson G, et al. Combined use of oligonucleotide and tissue microarrays identifies cancer/testis antigens as biomarkers in lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3971–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber J, Salgaller M, Samid D, Johnson B, Herlyn M, Lassam N, et al. Expression of the MAGE-1 tumor antigen is up-regulated by the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1766–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Smet C, De Backer O, Faraoni I, Lurquin C, Brasseur F, Boon T. The activation of human gene MAGE-1 in tumor cells is correlated with genome-wide demethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7149–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazer CA, Smith IM, Ochs MF, Begum S, Westra W, Chang SS, et al. Integrative discovery of epigenetically derepressed cancer testis antigens in NSCLC. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith IM, Glazer CA, Mithani SK, Ochs MF, Sun W, Bhan S, et al. Coordinated activation of candidate proto-oncogenes and cancer testes antigens via promoter demethylation in head and neck cancer and lung cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loukinov DI, Pugacheva E, Vatolin S, Pack SD, Moon H, Chernukhin I, et al. BORIS, a novel male germ-line-specific protein associated with epigenetic reprogramming events, shares the same 11-zinc-finger domain with CTCF, the insulator protein involved in reading imprinting marks in the soma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6806–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092123699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klenova EM, Morse HC, 3rd, Ohlsson R, Lobanenkov VV. The novel BORIS + CTCF gene family is uniquely involved in the epigenetics of normal biology and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filippova GN, Fagerlie S, Klenova EM, Myers C, Dehner Y, Goodwin G, et al. An exceptionally conserved transcriptional repressor, CTCF, employs different combinations of zinc fingers to bind diverged promoter sequences of avian and mammalian c-myc oncogenes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2802–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet. 2001;17:520–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki T, Kosaka-Suzuki N, Pack S, Shin DM, Yoon J, Abdullaev Z, et al. Expression of a testis-specific form of Gal3st1 (CST), a gene essential for spermatogenesis, is regulated by the CTCF paralogous gene BORIS. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2473–84. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01093-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vatolin S, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Flanagan PT, Custer M, Loukinov DI, et al. Conditional expression of the CTCF-paralogous transcriptional factor BORIS in normal cells results in demethylation and derepression of MAGE-A1 and reactivation of other cancer-testis genes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7751–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong JA, Kang Y, Abdullaev Z, Flanagan PT, Pack SD, Fischette MR, et al. Reciprocal binding of CTCF and BORIS to the NY-ESO-1 promoter coincides with derepression of this cancer-testis gene in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7763–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun L, Huang L, Nguyen P, Bisht KS, Bar-Sela G, Ho AS, et al. DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3B activate BAG-1 expression via recruitment of CTCFL/BORIS and modulation of promoter histone methylation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2726–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iizuka M, Smith MM. Functional consequences of histone modifications. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:154–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger SL. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:142–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottomley MJ. Structures of protein domains that create or recognize histone modifications. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:464–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, et al. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–4. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116–20. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:73–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen P, Bar-Sela G, Sun L, Bisht KS, Cui H, Kohn E, et al. BAT3 and SET1A form a complex with CTCFL/BORIS to modulate H3K4 histone dimethylation and gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6720–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00568-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahin U, Tureci O, Chen YT, Seitz G, Villena-Heinsen C, Old LJ, et al. Expression of multiple cancer/testis (CT) antigens in breast cancer and melanoma: basis for polyvalent CT vaccine strategies. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:387–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981029)78:3<387::AID-IJC22>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tajima K, Obata Y, Tamaki H, Yoshida M, Chen YT, Scanlan MJ, et al. Expression of cancer/testis (CT) antigens in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang Y, Hong JA, Chen GA, Nguyen DM, Schrump DS. Dynamic transcriptional regulatory complexes including BORIS, CTCF and Sp1 modulate NY-ESO-1 expression in lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4394–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiorentino FP, Macaluso M, Miranda F, Montanari M, Russo A, Bagella L, et al. CTCF and BORIS Regulate Rb2/p130 Gene Transcription: A Novel Mechanism and a New Paradigm for Understanding the Biology of Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:225–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Jungbluth AA, Old LJ, Chen YT. Cancer/testis antigens: an expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:22–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caballero OL, Chen YT. Cancer/testis (CT) antigens: potential targets for immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2014–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghafouri-Fard S, Modarressi MH. Cancer-testis antigens: potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:395–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Primers used for qRT-PCR, ChIP, bisulfite sequencing and QMSP.

Figure S1. Promoter regions of MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 analyzed for BORIS binding by ChIP are shown. Transcription start sites are labeled +1. Exons are shown in uppercase. Promoters and introns are shown in lowercase. ChIP primers are underlined and shown in bold.

Figure S2. Promoter region of MAGEA3 analyzed by bisulfite sequencing and QMSP is shown. Transcription start site is labeled +1. Exon 1 is shown is in uppercase. Promoter region and intron are shown in lowercase. CpG dinucleotides are shaded and underlined.