Abstract

Objective

Among a random sample of emergency department (ED) patients, determine the extent to which reported risk for HIV is related to ever having been tested for HIV.

Methods

A random sample of 18–64-year-old patients at an urban, academic, adult ED were surveyed about their history of ever having been tested for HIV and their reported HIV risk behaviors. A reported HIV risk score was calculated from the survey responses and divided into four levels, based upon quartiles of the risk scores. Pearson’s X2 testing was used to compare HIV testing history and level of reported HIV risk. Logistic regression models were created to investigate the association between level of reported HIV risk and the outcome of ever having been tested for HIV.

Results

Of the 557 participants, 62.1% were female. A larger proportion of females than males (71.4% versus 60.6%; p<0.01) reported they ever had been tested for HIV. Among the 211 males, 11.4% reported no HIV risk, and among the 346 females, 10.7% reported no HIV risk. The proportion of those who had been tested for HIV was greater among those reporting any risk, compared to those reporting no risk, for females (75.4% vs. 37.8%; p<0.001), but not for males (59.9% vs. 66.7%; p<0.52). However, certain high-risk behaviors, such as a history of injection-drug use, were associated with prior HIV testing for both genders. In the logistic regression analyses, there was no relationship between increasing level of reported HIV risk and a history of ever having been tested for HIV for males. For females, a history of ever having been tested was related to increasing level of reported risk, but not in a linear fashion.

Conclusions

The relationship between reported HIV risk and history of testing among these ED patients was complex and differed by gender. Among these patients, having greater risk did not necessarily mean a higher likelihood of having ever been tested for HIV.

Introduction

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s called for expanded HIV testing in all healthcare settings, including emergency departments (EDs).1 At the time of the release of the recommendations, little was known about the extent to which ED patients had been tested for HIV, which is information that is important in planning for the implementation of HIV screening programs. In our research, we found that 55% of a random sample of 2,107 patients in our ED had ever been tested for HIV2. Of particular interest, a history of prior HIV testing was not uniform among patients, but instead varied according to patient demographic characteristics. Patients who were male, white, married, and had private health-care insurance were less likely ever to have been tested for HIV. Patients who were 21-years-old and younger or 52-years-old and older were less likely to have been tested for HIV than those 22–52-years-old. In a related study, we observed that uptake of screening when offered to ED patients in an opt-in fashion also varied by patient demographic characteristics.3 The results of these studies indicate that ED-based HIV screening programs will need to be sensitive and responsive to patient demographic when designing and implementing HIV screening programs.

In addition to patient demography, it is likely that risk for HIV is a motivator for either seeking HIV testing or having been offered testing. In fact, previous CDC HIV testing recommendations have emphasized the linkage of risk and need for HIV testing.4–10 It would be logical to assume that because of prior CDC recommendations and the natural link between risk and HIV infection, those who are at greater risk for HIV are more likely to have been tested for HIV. Researchers examining the responses from several national surveys have found that a reported history of prior HIV testing is generally higher among those at risk, although this relationship, as well as risk, varies by demographic characteristics.11–16 For example, Anderson, et al., using data from the National Survey of Family Growth, observed that among 15–44-year-olds in the US, more males (13.0%) than females (10.8%) reported any sexual or drug-related risk or treatment for a sexually transmitted disease within the past year. However, of those reporting these risks, fewer males (64%) than females (69.3%) ever had been tested for HIV.13 In comparison, 48.8% of males and 53.2% of females who did not report these risks had been tested for HIV.

In this study, we sought to expand upon our prior research examining correlates of prior HIV testing among ED patients. Our objective was to investigate to what extent reported HIV risk behaviors are related to prior HIV testing among ED patients. In brief, we wanted to know if ED patients at higher risk had been tested for HIV. Although the capacity for HIV risk from sexual contact is different for females and males (e.g., men-who-have-sex-with men or MSMs), we were also interested if the relationship between HIV risk and history of HIV testing varied by gender. Gender-related differences, if they exist, would inform any future interventions or HIV screening programs in EDs.

Methods

Study design and setting

This investigation was a part of a larger randomized, controlled trial of HIV screening in the ED. This portion involved surveying 18–64-year-old English-speaking ED patients with a sub-critical illness or injury about their history of HIV testing and reported HIV risk behaviors. The study was conducted at an urban, academic, not-for-profit, adult ED in New England from October 1, 2007 until September 30, 2008. During this period, the ED had approximately 54,000 visits for a sub-critical illness or injury by English-speaking 18–64-year-olds. This ED does not have a standing HIV screening program, although rapid diagnostic testing is available and there have been several studies of HIV screening at this ED. The institutional review board of the hospital approved the study.

Study participant selection

As outlined in detail previously, we employed a three-level plan to randomly select patients to assess their eligibility and possibly include them in the study.3 This plan is briefly summarized here. We randomly selected: (1) sixteen dates per month during which we conducted the study; (2) the eight-hour shifts that we conducted the study on those dates; and (3) the patients we approached to assess their study eligibility during those shifts. The shifts were randomly selected according to a weighting scheme that reflected the typical patterns of ED patient volume during a typical 24-hour period (40% were day, 50% were evening, and 10% were night shifts). During each shift, we randomly selected 80% of the patients present in the ambulatory care and the urgent care areas of the ED and assessed them for study eligibility. Patients in the psychiatric/substance abuse care and critical care areas of the ED were not assessed for study eligibility. ED staff members were not permitted to encourage or refer patients to be in the study.

A research assistant assessed the eligibility of ED patients randomly selected for possible study inclusion by reviewing their ED medical records and then confirming their eligibility through an in-person interview. ED patients whose medical record indicated they were not eligible for the study were not interviewed. Patients were eligible for the study if they: were 18–64-years old; English-speaking; not critically ill or injured; not incarcerated, under arrest, or on home confinement; not presenting for a psychiatric illness; not known to be HIV infected; not participating in an HIV vaccine trial; not intoxicated; and did not have a physical disability or mental impairment that prevented them from providing consent or participating in the study. All patients confirmed study eligible were invited to enroll. No incentives were offered to participants.

Measurements

Participants were interviewed about their demographic characteristics and HIV testing history using instruments developed and employed in prior studies.2, 3, 17, 18 In addition, participants completed the “HIV risk questionnaire” using an audio-computer assisted self-interviewer (ACASI). The development and content of this questionnaire have been provided in detail previously, and the questions relevant to this analysis are included in this manuscript.18 In brief, the “HIV risk questionnaire” is a multiple-choice, closed-response questionnaire that asks participants to report their injection-drug use and sexual HIV risk behaviors. Participants were asked if they had engaged in selected injection-drug and sexual HIV risk behaviors within the prior ten years. A ten-year time period was used because this reflects the usual time during which an HIV infection is diagnosed, since AIDS is typically manifested 5–10 years after an HIV exposure.19–24

The questionnaire consists of primary questions, which introduce a topic, and a consecutive series of follow-up questions, which were asked of participants who answer affirmatively to the primary questions. Therefore, the number of reported HIV risk behavior questions each participant received was dependent upon their responses to the questions, which was a function of the number of HIV risk behaviors they reported. Because males and females differ in the types of sexual risks they can engage in, e.g., females having unprotected sex with MSMs, the sexual reported HIV risk questions are gender-specific. Accordingly, there are a total of 16 possible reported HIV risk behavior questions for females and 26 for males.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA 9.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The results of the study eligibility assessment and enrollment procedures were summarized and diagramed. Study participants who refused to answer questions and those who did not know the answers to questions about their demographic characteristics or whether or not they had been tested for HIV were excluded from the analysis. Missing data were not imputed. Summary statistics of demographic characteristics, including the median and inter-quartile range (IQR) for age, were calculated for both genders. The demographic characteristics of participants previously and not previously tested for HIV were compared by gender using Pearson’s X2 test. For these and all other analyses, differences were considered to be significant at the α=0.05 level.

As described previously, we calculated a reported HIV risk score to summarize the responses from the “HIV risk questionnaire”.18 Higher scores represented a greater number of HIV risk behaviors reported. The reported HIV risk score was the sum of each participant’s responses divided by the total possible points for all questions. The maximum possible scores were 36 for females and 61 for males. The reported HIV risk score was divided into quartiles, which indicated four increasing levels of reported HIV risk behaviors in this population. Summary statistics were calculated for the reported risk score (mean, standard deviation, and proportion) by reported risk level. Pearson’s X2 testing was used to compare the HIV testing history and reported risk score level by gender.

Logistic regression models stratified by gender were created to investigate the association between the level of reported HIV risk and the outcome of a history of ever having been tested for HIV. Our prior research indicated variations in HIV testing history according to patient demographic characteristics.2 Demographic characteristics associated with a history of prior HIV testing in univariable logistic regression at the α=0.05 level were included in the multivariable models. The reference groups for the models were those with the lowest proportion of ever having been tested for HIV. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated.

Results

Description of study participants

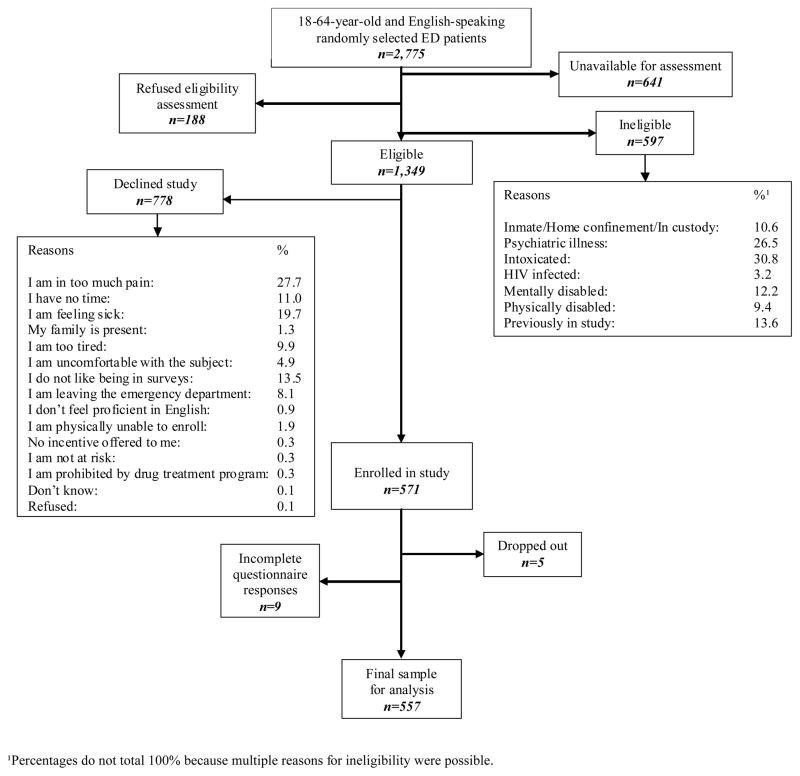

The Figure depicts the results of the study eligibility assessment and enrollment procedures for the study. Five hundred fifty-seven participants were included in this analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participants by gender. Of all 557 participants, 62.1% were female. The median age was 35 (IQR: 24–47) years for males and 28 (IQR: 22–39) years for females. Among all participants, most were white, never married, had private healthcare insurance, and had twelve or fewer years of formal education. Sixty-seven percent of the participants had been tested for HIV. A larger proportion of females than males (71.4% versus 60.6%; p<0.01) reported that they had been tested for HIV. Table 1 also provides a comparison of participants by demographic characteristics and history of ever having been tested for HIV. As shown, ethnicity/race and years of formal education were not associated with a history of prior HIV testing.

Figure 1.

Eligibility assessment and enrollment flow diagram

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and HIV testing history

| Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All males | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 1 p-value | All females | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 1 p-value | |

| n=211 | n=128 | n=83 | n=346 | n=247 | n=99 | |||

| Demographic characteristics | % | % | % | p | % | % | % | p |

| Ethnicity/Race | 0.11 | 0.09 | ||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 61.1 | 59.4 | 63.9 | 63.0 | 63.6 | 61.6 | ||

| White, Hispanic | 12.3 | 11.7 | 13.3 | 15.9 | 13.8 | 21.2 | ||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 16.6 | 19.5 | 12.1 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 8.1 | ||

| Black, Hispanic | 6.2 | 7.8 | 3.6 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 5.1 | ||

| Other | 3.8 | 1.6 | 7.1 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 4.0 | ||

| Partner status | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Never Married | 47.4 | 39.8 | 59.1 | 49.1 | 44.5 | 60.6 | ||

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 14.2 | 18.7 | 7.2 | 14.5 | 15.5 | 12.1 | ||

| Married | 26.5 | 26.7 | 26.5 | 19.3 | 19.8 | 18.2 | ||

| Unmarried couple | 11.9 | 14.8 | 7.2 | 17.1 | 20.2 | 9.1 | ||

| Insurance status | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Private | 40.2 | 29.7 | 56.6 | 41.9 | 36.8 | 54.6 | ||

| Governmental | 29.9 | 39.1 | 15.7 | 41.6 | 46.6 | 29.3 | ||

| None | 29.9 | 31.2 | 27.7 | 16.5 | 16.6 | 16.1 | ||

| Years of formal education | 0.24 | 0.50 | ||||||

| Grades 1–11 | 22.2 | 25.8 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 19.0 | 13.1 | ||

| Grade 12/GED2 | 32.8 | 32.0 | 33.7 | 26.9 | 27.5 | 25.3 | ||

| College/Graduate studies | 45.0 | 42.2 | 49.5 | 55.8 | 53.5 | 61.6 | ||

| Age groups (in years) | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 18–25 | 28.4 | 16.4 | 47.0 | 40.5 | 35.6 | 52.5 | ||

| 26–35 | 22.8 | 25.8 | 18.1 | 30.1 | 35.6 | 16.2 | ||

| 36–45 | 19.0 | 23.4 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 15.8 | 8.1 | ||

| 46–55 | 24.6 | 29.7 | 16.8 | 11.3 | 9.7 | 15.1 | ||

| 56–64 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 8.1 | ||

p-values reflect comparison of those Previously tested for HIV vs. Never Tested for HIV by demographic characteristic and gender using Pearson’s X2 testing

General equivalency degree

Reported HIV risk behaviors

Table 2 provides the participant responses to the “HIV risk questionnaire” by history of ever having been tested for HIV and by gender. Among females, a history of any injection-drug use, all of heterosexual sexual behaviors, and unprotected sex with MSMs were associated with ever having been tested for HIV. Among males, a history of any injection-drug use, sharing of injection-drug needles or syringes, and unprotected anal/vaginal sexual intercourse with women who inject drugs were associated with ever having been tested for HIV.

Table 2.

Responses to the “HIV risk questionnaire” by HIV testing history and gender

| MALES | FEMALES | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary questions and follow-up questions sequence | Question | Answer choices | All males | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 1 p-value | All females | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 1 p-value | |||

| Primary questions | Follow-up questions2 | % | % | % | P | % | % | % | P | ||||

| a | b | c | Section 1: Injection drug use | n=211 | n=128 | n=83 | n=346 | n=247 | n=99 | ||||

| 1 | In the past ten years, have you injected “street drugs” such as heroin, cocaine or crystal meth? | Yes | 12.8 | 18.0 | 4.8 | 0.01 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 2.0 | 0.01 | |||

| No | 87.2 | 82.0 | 95.2 | 93.6 | 92.7 | 96.0 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1a | In the past ten years, have you injected “street drugs” with a needle or syringe that had been used by someone else first? | Yes | 6.2 | 8.6 | 2.4 | 0.02 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 0.22 | |||

| No | 6.6 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 87.2 | 82.0 | 95.2 | 94.2 | 92.7 | 98.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1b | Now think about the times in the past ten years you injected “street drugs” with a needle or syringe that had been used by someone else first. Were there times when the needle or syringe was NOT cleaned with bleach and water before you used it? | Yes | 4.7 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 0.15 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.61 | |||

| No | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 93.9 | 91.4 | 97.6 | 97.4 | 96.8 | 99.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1c1 | Please think only about the times in the past ten years you used a needle or syringe that was not cleaned before you used it. Were there times you knew the needle or syringe had been used by someone who had HIV or AIDS? | Yes | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.84 | |||

| No | 4.3 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 95.2 | 93.0 | 98.8 | 97.7 | 97.2 | 99.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1c2 | Please think only about the times in the past ten years you used a needle or syringe that was not cleaned before you used it. Were there times you were UNSURE if the needle or syringe had been used by someone who had HIV or AIDS? | Yes | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 0.17 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.84 | |||

| No | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 95.3 | 93.0 | 98.8 | 97.6 | 97.2 | 99.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Section 2: Heterosexual sexual behaviors | n=211 | n=128 | n=83 | n=346 | n=247 | n=99 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2 | In the past ten years, have you had vaginal or anal sex with a (woman/man)? | Yes | 85.3 | 82.8 | 89.2 | 0.20 | 88.7 | 94.0 | 75.8 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 14.7 | 17.2 | 10.8 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 23.2 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2a | In the past ten years, how many different (women/men) did you have vaginal or anal sex with when you did NOT use a condom? [Count each(woman/man) once.] | 21 or more | 3.8 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 0.82 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 0.00 | |||

| 11–20 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 2.0 | |||||||

| 6–10 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 3.0 | |||||||

| 2–5 | 28.9 | 26.6 | 32.5 | 36.1 | 38.9 | 29.3 | |||||||

| 1 | 34.1 | 32.8 | 36.1 | 35.0 | 34.8 | 35.4 | |||||||

| None | 7.1 | 6.3 | 8.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.0 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 14.7 | 17.1 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 6.1 | 24.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b1 | Please think only about the (women/men) you had vaginal or anal sex with in the past ten years when (you/they) did not use a condom. Do you KNOW if any of these (women/men) had HIV or AIDS? That is, did any of these (women/men] have a positive HIV test, have an HIV infection, or have AIDS? | Yes | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 0.32 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 73.5 | 70.3 | 78.3 | 72.8 | 74.9 | 67.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 5.7 | 7.8 | 2.4 | 9.3 | 10.9 | 5.1 | |||||||

| N/A | 18.4 | 18.8 | 18.1 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b2 | Please think only about the (women/men) you had vaginal or anal sex with in the past ten years when (you/they) did not use a condom. Are you UNSURE if any of these (women/men) had HIV or AIDS? That is, did you have vaginal or anal sex without a condom with (women/men) you never knew or never asked if they had HIV or AIDS? | Yes | 31.3 | 32.8 | 28.9 | 0.90 | 26.0 | 27.1 | 23.2 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 48.8 | 46.9 | 51.8 | 57.5 | 60.3 | 50.5 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 18.5 | 18.7 | 18.1 | 14.5 | 9.8 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b3 | Please think only about the (women/men) you had vaginal or anal sex with in the past ten years when (you/they) did not use a condom Have any of these (women/men) ever injected “street drugs” such as heroin, cocaine or crystal meth? | Yes | 10.4 | 14.8 | 3.6 | 0.05 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 5.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 65.9 | 60.9 | 73.5 | 67.3 | 68.0 | 65.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 5.2 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 3.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 18.5 | 18.8 | 18.1 | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b4 | Please think only about the (women/men) you had vaginal or anal sex with in the past ten years when (you/they) did not use a condom. Did any of these (women/men) have a sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes | Yes | 7.1 | 10.2 | 2.4 | 0.18 | 11.9 | 13.4 | 8.1 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 63.5 | 60.2 | 68.7 | 64.2 | 66.0 | 59.6 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 10.9 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 9.5 | 10.9 | 6.1 | |||||||

| N/A | 18.5 | 18.7 | 18.1 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b5 | In the past ten years, have you had vaginal or anal sex with someone so they would give you money, drugs or other things? | Yes | 5.2 | 7.8 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 83.4 | 79.7 | 89.2 | 79.8 | 83.4 | 70.7 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.4 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b6 | In the past ten years, have you used money, drugs or other things to pay for vaginal of anal sex? | Yes | 8.1 | 10.2 | 4.8 | 0.30 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 79.6 | 75.8 | 85.5 | 83.2 | 87.5 | 72.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.3 | 12.4 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b7 | In the past ten years, have you had vaginal or anal sex when you were drunk, high or stoned? | Yes | 52.6 | 52.3 | 53.0 | 0.89 | 47.7 | 52.2 | 36.4 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 35.6 | 34.4 | 37.4 | 37.9 | 38.1 | 37.4 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.3 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2b8 | In the past ten years, have you had a sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes or syphilis? | Yes | 7.1 | 9.4 | 3.6 | 0.39 | 15.0 | 18.6 | 6.1 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 79.2 | 75.8 | 84.3 | 69.9 | 71.3 | 66.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.3 | 12.5 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Section 3: Potentiators of HIV sexual risk | n=211 | n=128 | n=83 | n=346 | n=247 | n=99 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3b13 | In the past ten years, have you had vaginal or anal sex with someone so they would give you money, drugs or other things? | Yes | 52 | 7.8 | 1.2 | 0.08 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 83.4 | 79.7 | 89.2 | 79.8 | 83.4 | 70.7 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.4 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3b23 | In the past ten years, have you used money, drugs or other things to pay for vaginal or anal sex? | Yes | 8.1 | 10.2 | 4.8 | 0.30 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 79.6 | 75.8 | 85.6 | 83.2 | 87.5 | 72.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.90 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.4 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3b33 | In the past ten years, have you had vaginal or anal sex when you were drunk, high or stoned? | Yes | 52.6 | 52.3 | 53.0 | 0.89 | 47.7 | 52.2 | 36.4 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 35.6 | 34.4 | 37.4 | 37.9 | 38.1 | 37.4 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.4 | 12.5 | 9.6 | 14.4 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3b43 | In the past ten years, have you had a sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes or syphilis? | Yes | 7.1 | 9.4 | 3.6 | 0.39 | 13.0 | 18.6 | 6.1 | 0.00 | |||

| No | 79.2 | 75.8 | 84.3 | 69.9 | 71.3 | 66.7 | |||||||

| Don’t know | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | |||||||

| N/A | 11.3 | 12.5 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.2 | |||||||

| Primary questions and follow-up questions sequence | Question | Answer choices | All | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 1 p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary questions | Follow-up questions2 | % | % | % | P | |||

| a | b | Section 4: Male-only sexual behaviors | n=211 | n=128 | n=83 | |||

| 4 | In the past ten years, have you had anal sex with a man? | Yes | 4.7 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 0.11 | ||

| No | 94.8 | 92.1 | 98.8 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4a | Think of men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when YOUR penis was inside of HIS butt (you were the “top”). With how many of these men did you have anal sex when YOU did NOT use a condom? (Count each man once.) | 21 or more | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.67 | ||

| 11–20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| 6–10 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| 2–5 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | |||||

| 1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | |||||

| None- I used a condom | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 95.2 | 92.9 | 98.8 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4a1 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when you were the “top” and you did not use a condom. Do you KNOW if any of these men had HIV or AIDS? That is, did any of these men have a positive HIV test, have an HIV infection, or have AIDS? | Yes | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.35 | ||

| No | 3.3 | 4.7 | 1.2 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 95.2 | 93.0 | 98.8 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4a2 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when you were the “top” and you did not use a condom. Are you UNSURE if any of these men had HIV or AIDS? That is, did you have sex without a condom with men you never knew or never asked if they had HIV infection or had AIDS? | Yes | 2.8 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.09 | ||

| No | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.2 | |||||

| N/A | 95.3 | 93.0 | 98.8 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4a3 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when you were the “top” and you did not use a condom. Have any of these men ever injected “street drugs” such as heroin, cocaine or crystal meth? | Yes | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.31 | ||

| No | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.2 | |||||

| Don’t know | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 95.3 | 93.0 | 98.8 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4a4 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when you were the “top” and you did not use a condom. Did any of these men have a sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes or syphilis? | Yes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.12 | ||

| No | 4.3 | 6.2 | 1.2 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 95.2 | 93.0 | 98.8 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4b | Think of men you had anal sex within the past ten years when HIS penis was inside of YOUR butt (you were the “bottom”). With how many of these men did you have anal sex with when HE did NOT use a condom? (Count each man once.) | 21 or more | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.67 | ||

| 11–20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| 6–10 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| 2–5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | |||||

| None - They/He used a condom | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | |||||

| 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | ||||||

| None- I was not the bottom | 95.2 | 92.9 | 98.8 | |||||

| N/A | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4b1 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when he did not use a condom when you were the “bottom”. Do you KNOW if any of these men had HIV or AIDS? That is, did any of these men have a positive HIV test, have an HIV infection or have AIDS? | Yes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.71 | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 98.5 | 97.6 | 100.0 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4b2 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when he did not use a condom when you were the “bottom”. Are you UNSURE if any of these men had HIV or AIDS? That is, did you have anal sex without a condom with men you never knew or never asked if they had HIV or AIDS? | Yes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.71 | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 98.5 | 97.6 | 100.0 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3b3 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when he did not use a condom when you were the “ bottom”. Have any of these men ever injected “street drugs” such as heroin, cocaine or crystal meth? | Yes | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.00 | ||

| No | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 98.5 | 97.6 | 100.0 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4b3 | Please think only about the men you had anal sex with in the past ten years when he did not use a condom when you were the “bottom” Did any of these men have a sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, genital herpes or syphilis? | Yes | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.00 | ||

| No | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| Don’t know | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |||||

| N/A | 98.5 | 97.6 | 100.0 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Section 5: Female-only sexual behaviors | n=346 | n=247 | n=99 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 5 | Please think only about the men you had vaginal or anal sex within the past ten years when they did not use a condom Have any of these men ever had sex with another man? | Yes | 4.3 | 5.3 | 2.0 | 0.00 | ||

| No | 67.9 | 67.6 | 68.7 | |||||

| Don’t know | 13.3 | 17.4 | 3.0 | |||||

| N/A | 14.5 | 9.7 | 26.3 | |||||

Participants received follow-up questions if the answer to the primary questions were yes. For example, for questions 2b1 through 2b4, participants received these questions if they reported having 1 or more different sexual partners for question 2a. N/A indicates that the question was not received because of a no or none response to the prior question.

p-values are shown for the results of Pearson’s X2 or Fisher’s exact tests comparing participants by history of HIV testing.

Questions were asked of those who indicated they had one or more unprotected sexual partners.

Association between reported HIV risk and history of HIV testing

Among the 211 males, 11.4% reported no HIV risk and among the 346 females, 10.7% reported no HIV risk. The proportion of those who had been tested for HIV was greater among those reporting any risk, compared to those reporting no risk, for females (75.4% vs. 37.8%; p<0.001), but not for males (59.9% vs. 66.7%; p<0.52). Table 3 shows the proportion of patients previously tested for HIV according to the levels of reported HIV risk. For males, the proportion of those previously tested for HIV was highest for males in the highest HIV risk score level, but was similar for all other levels. For females, the proportion of those previously tested for HIV tended to increase as HIV risk score level increased, but not in a linear fashion.

Table 3.

HIV testing history by risk level and gender

| Males | Females | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | Previously tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | |||||||||

| Risk level | n | HIV risk score mean (sd) | % | HIV risk score mean (sd) | % | 1p-value | n | HIV risk score mean (sd) | % | HIV risk score mean (sd) | % | 1p-value |

| 1 | 68 | 0.03(0.03) | 55.9 | 0.04(0.03) | 44.1 | 109 | 0.08(0.05) | 55.1 | 0.06(0.05) | 44.9 | ||

| 2 | 38 | 0.09(0.01) | 55.3 | 0.09(0.01) | 44.7 | 100 | 0.17(0.02) | 71.0 | 0.17(0.02) | 29.0 | ||

| 3 | 57 | 0.14(0.02) | 57.9 | 0.13(0.02) | 42.1 | 63 | 0.25(0.02) | 87.3 | 0.26(0.02) | 12.7 | ||

| 4 | 48 | 0.27(0.08) | 75.0 | 0.23(0.07) | 25.0 | 74 | 0.43(0.11) | 82.4 | 0.41(0.10) | 17.6 | ||

| All levels | 211 | 0.14(0.10) | 60.6 | 0.11(0.07) | 39.4 | 0.14 | 346 | 0.23(0.14) | 71.4 | 0.15(0.13) | 28.6 | 0.00 |

p-values reflect comparison of those Previously tested for HIV vs. Never Tested for HIV by risk level and gender using Pearson’s X2 testing

Table 4 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses that aimed to evaluate the relationship of reported HIV risk behaviors and history of ever having been tested for HIV. For males, there was a trend in the adjusted model for an increased odds of prior HIV testing for those in the highest HIV risk score level. Being in age groups 26–55 and having governmental insurance were related to ever having been tested for HIV for males in the adjusted model. For females, the odds of prior HIV testing were greater for those at higher HIV risk score levels, but not in a step-wise fashion. Being in age group 26–35, being a part of an unmarried couple, and having governmental insurance were related to ever having been tested for HIV for females in the adjusted model.

Table 4.

Association of HIV risk level and history of previous HIV testing by gender

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | Univariable | Multivariable | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Risk level | ||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 2 | 0.98 (0.44–2.17) | 1.09 (0.44–2.66) | 2.0 (1.13–3.55) | 2.03 (1.08–3.80) |

| 3 | 1.09 (0.53–2.21) | 1.24 (0.55–2.81) | 5.61 (2.44–12.90) | 5.82 (2.37–14.29) |

| 4 | 2.37 (1.05–5.32) | 2.51 (0.99–6.33) | 3.83 (1.89–7.78) | 3.75 (1.72–8.15) |

| Age groups | ||||

| 18–25 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 26–35 | 4.09 (1.82–9.17) | 3.27 (1.37–7.83) | 3.25 (1.72–6.12) | 2.77 (1.38–5.59) |

| 36–45 | 5.57 (2.29–13.58) | 4.73 (1.63–13.70) | 2.88 (1.25–6.64) | 2.59 (0.98–6.89) |

| 46–55 | 5.04 (2.24–11.34) | 3.45 (1.15–10.42) | 0.95 (0.46–1.96) | 0.91 (0.35–2.34) |

| 56–64 | 2.23 (0.61–8.18) | 1.24 (0.24–6.46) | 0.59 (0.21–1.67) | 0.61 (0.17–2.20) |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | Reference | Reference | ||

| White, Hispanic | 0.95 (0.41–2.23) | 0.63 (0.34–1.17) | ||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.74 (0.77–3.93) | 1.70 (0.75–3.87) | ||

| Black, Hispanic | 2.32 (0.61–8.85) | 1.40 (0.50–3.93) | ||

| Other | 0.23 (0.05–1.20) | 0.29 (0.06–1.34) | ||

| Partner status | ||||

| Never Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 3.84 (1.45–10.21 | 1.64 (0.49–5.52) | 1.73 (0.84–3.55) | 1.77 (0.65–4.79) |

| Married | 1.48 (0.76–2.89) | 1.60 (0.58–4.43) | 1.48 (0.79–2.77) | 1.85 (0.83–4.11) |

| Unmarried couple | 3.04 (1.12–8.25) | 2.24 (0.72–6.95) | 3.03 (1.39–6.59) | 2.88 (1.25–6.64) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Private | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Governmental | 4.76 (2.26–10.02) | 4.23 (1.73–10.39) | 2.35 (1.39–3.99) | 2.41 (1.33–4.38) |

| None | 2.15 (1.10–4.19) | 2.09 (0.93–4.66) | 1.52 (0.78–2.97) | 1.53 (0.72–3.25) |

| Years of formal education | ||||

| Grades 1–11 | 1.79 (0.85–3.77) | 1.67 (0.84–3.31) | ||

| Grade 12 | 1.11 (0.59–2.09) | 1.26 (0.73–2.18) | ||

| College/Graduate studies | Reference | Reference | ||

Discussion

These study results indicate that the relationship between HIV risk and testing among ED patients is complex and differs by gender. Among males, those at no reported risk were just as likely as those with any risk to have been tested for HIV, and high proportions of those at every risk level had not been tested. Among females, increasing risk is modestly related to prior HIV testing, but not in a linear fashion, and many at every risk level have not been tested. Although 89.3% of males and 88.6% reported any risk, only 60.6% of males and 71.4% of females ever had been tested for HIV, and a high proportion of those even at the highest levels of reported HIV risk (25.0% of males and 17.6% of females) have never been tested for HIV. The reasons for these differences by gender are not known.

The responses from the questionnaire illustrate that many of those with particular individual risk behaviors have not been tested previously. For example, of females not previously tested for HIV, 2% had injected drugs, 72.7% had unprotected vaginal and/or anal intercourse with at least one male partner, 23.2% had unprotected vaginal and/or anal intercourse with at least one male of unknown HIV status, and 6.1% had a sexually transmitted disease in the prior ten years. Among males not previously tested for HIV, 4.8% had injected drugs, 80.7% had unprotected vaginal and/or anal with at least one female partner, 28.9% had unprotected vaginal and/or anal at least one female of unknown HIV status, and 3.6% had a sexually transmitted disease in the prior ten years. The responses by risk also illustrate that certain risk behaviors, such as injection-drug use, are related more strongly than others to ever having been tested for HIV.

How can the results of this study be applied? On the one hand, supporters of widespread, non-targeted (or universal) HIV screening would note that the results demonstrate the need to decouple risk from HIV screening. In 2006, CDC recommended that initial HIV screening of patients in healthcare settings be decoupled from risk, although subsequent HIV screening among those previously tested can be risk-based, because many of those at risk have not been tested for HIV.1 On the other hand, those supportive of risk-based HIV testing might note that the results indicate opportunities for developing targeted interventions that motivate patients at risk to be tested, and that these interventions need to be responsive to gender as well as type of risk. For the emergency medicine clinician, the results do show that clinicians should not automatically assume that those at higher risk for HIV have been tested or will get tested. Emergency medicine clinicians are therefore encouraged to provide HIV testing whenever an infection might be present or a patient is at risk.

This study had several limitations. First, despite our efforts to obtain a representative sample of ED patients, the study findings might not be applicable to other EDs with different distributions of patient demographic characteristics, HIV testing histories, and HIV risk, or to patients who do not speak English or those who could not participate in the study. Second, although the questionnaire used in this study was rigorously developed, it has not yet been demonstrated to predict HIV infection, and therefore the reported HIV risk score cannot be interpreted to represent actual risk. There is no accepted standard for measuring risk or quantifying it. Our use of quartiles of risk, although logical, might not be the best representation of risk. Third, the lack of an apparent relationship between individual reported risk behaviors and HIV testing history could be due to their relative infrequency. For example, there were few MSMs in this sample, so importance of this risk might not have been well demonstrated in this study. Fourth, the study does not take into account self-perceived risk for HIV, which might have affected prior acceptance of HIV screening, when it was offered, or the extent to which study participants had opportunities to be tested previously, regardless of their risk for HIV. Fifth, reported HIV history might be inaccurate; patients might incorrectly assume that they had been previously tested as part of a medical evaluation, when in fact they had not. Because patients can be tested in a variety of healthcare and non-healthcare settings across time and geographic areas, as well as be tested anonymously, it was not possible to verify their HIV testing history. The relationship of interest, reported HIV risk and testing history, remains valid even if it actually measures belief about testing instead of a true history of ever having been tested for HIV.

Conclusions

Along with our prior research that showed demographic variations in HIV testing history2, this study provides further evidence that a history of prior HIV testing is not uniform among ED patients. Having greater risk did not necessarily mean a higher likelihood of having ever been tested for HIV. Most patients report at least some risk for an infection; however, a history of HIV testing is not linearly related to risk. The relationship between risk and HIV testing is complex, and appears to vary by gender.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Freelove conducted this study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Public Health from the University of Massachusetts. Dr. Merchant and this study were supported by a career development grant from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23 A1060363). Dr. Mayer was supported by the Center for AIDS Research at Lifespan/Tufts/Brown (P30 AI42853).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Eric Feuchtbaum who helped with the development and cognitive-based assessments of the questionnaire used in this study, as well as the staff and patients of the Rhode Island Hospital Emergency Department who made this study possible.

References

- 1.Branson B, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, Clark JE. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports Recommended Reports. 2006 Sept 22;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant RC, Catanzaro BM, Seage GR, 3rd, et al. Demographic variations in HIV testing history among emergency department patients: implications for HIV screening in US emergency departments. J Med Screen. 2009;16(2):60–66. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.008058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merchant RC, Seage GR, III, Mayer KH, Clark MA, DeGruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Supplement 3):27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provisional Public Health Service inter-agency recommendations for screening donated blood and plasma for antibody to the virus causing acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1985 Jan 11;34(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Recommendations for preventing transmission of infection with human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus in the workplace. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1985 Nov 15;34(45):681–686. 691–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Additional recommendations to reduce sexual and drug abuse-related transmission of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1986 Mar 14;35(10):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Service guidelines for counseling and antibody testing to prevent HIV infection and AIDS. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1987 Aug 14;36(31):509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recommendations for HIV testing services for inpatients and outpatients in acute-care hospital settings. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993 Jan 15;42(RR-2):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U. S. Public Health Service recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus counseling and voluntary testing for pregnant women. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995 Jul 7;44(RR-7):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-19):1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson JE, Chandra A, Mosher WD. HIV testing in the United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2005 Nov 8;363:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JE, Carey JW, Taveras S. HIV testing among the general US population and persons at increased risk: information from national surveys, 1987–1996. Am J Public Health Jul. 2000;90(7):1089–1095. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JE, Mosher WD, Chandra A. Measuring HIV risk in the U.S. population aged 15–44: results from Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Adv Data. 2006 Oct 23;377:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson JE, Santelli J, Mugalla C. Changes in HIV-related preventive behavior in the US population: data from national surveys, 1987–2002. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Oct 1;34(2):195–202. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200310010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtzman D, Bland SD, Lansky A, Mack KA. HIV-related behaviors and perceptions among adults in 25 states: 1997 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2001 Nov;91(11):1882–1888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Persons tested for HIV--United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008 Aug 8;57(31):845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merchant R, Gee E, Clark M, Mayer K, Seage GI, DeGruttola V. Comparison of patient comprehension of rapid HIV pre-test fundamentals by information delivery format in an emergency department setting. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(7) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchant RC, Clark MA, Langan TJ, IV, Seage GR, III, Mayer KH, DeGruttola VG. Effectiveness of increasing emergency department patients’ self-perceived risk for being Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-infected through audio computer self interview based feedback about reported HIV risk behaviors. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1143–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The AIDS incubation period in the UK estimated from a national register of HIV seroconverters. UK Register of HIV Seroconverters Steering Committee. Aids. 1998 Apr 16;12(6):659–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey NT. A revised assessment of the HIV/AIDS incubation period, assuming a very short early period of high infectivity and using only San Francisco public health data on prevalence and incidence. Stat Med. 1997 Nov 15;16(21):2447–2458. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971115)16:21<2447::aid-sim681>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevret S, Costagliola D, Lefrere JJ, Valleron AJ. A new approach to estimating AIDS incubation times: results in homosexual infected men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992 Dec;46(6):582–586. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.6.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacchetti P, Moss AR. Incubation period of AIDS in San Francisco. Nature. 1989 Mar 16;338(6212):251–253. doi: 10.1038/338251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tassie JM, Grabar S, Lancar R, Deloumeaux J, Bentata M, Costagliola D. Time to AIDS from 1992 to 1999 in HIV-1-infected subjects with known date of infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 May 1;30(1):81–87. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Time from HIV-1 seroconversion to AIDS and death before widespread use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative re-analysis. Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival including the CASCADE EU Concerted Action. Concerted Action on SeroConversion to AIDS and Death in Europe. Lancet. 2000 Apr 1;355(9210):1131–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]