Abstract

Treatment of Sprague-Dawley rats with AY9944, an inhibitor of 3β-hydroxysterol-Δ7-reductase (Dhcr7), leads to elevated levels of 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) and reduced levels of cholesterol in all biological tissues, mimicking the key biochemical hallmark of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS). Fourteen 7-DHC-derived oxysterols previously have been identified as products of free radical oxidation in vitro; one of these oxysterols, 3β,5α-dihydroxycholest-7-en-6-one (DHCEO), was recently identified in Dhcr7-deficient cells and in brain tissues of Dhcr7-null mouse. We report here the isolation and characterization of three novel 7-DHC-derived oxysterols (4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC and 24-hydroxy-7-DHC) in addition to DHCEO and 7-ketocholesterol (7-kChol) from the brain tissues of AY9944-treated rats. The identities of these five oxysterols were elucidated by HPLC-ultraviolet (UV), HPLC-MS, and 1D- and 2D-NMR. Quantification of 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, DHCEO, and 7-kChol in rat brain, liver, and serum were carried out by HPLC-MS using d7-DHCEO as an internal standard. With the exception of 7-kChol, these oxysterols were present only in tissues of AY9944-treated, but not control rats, and 7-kChol levels were markedly (>10-fold) higher in treated versus control rats. These findings are discussed in the context of the potential involvement of 7-DHC-derived oxysterols in the pathogenesis of SLOS.—.

Keywords: cholesterol, cholesterol/biosynthesis, lipids/peroxidation, 7-dehydrocholesterol

7-Dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) accumulates in tissues and fluids of patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS), a recessive disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding 3β-hydroxysterol-Δ7-reductase (DHCR7; EC 1.3.1.21), the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of 7-DHC to cholesterol (1–7). This defect in cholesterol biosynthesis typically results in profoundly reduced levels of cholesterol in bodily tissues and fluids of SLOS patients, compared with normal unaffected individuals. SLOS is characterized by a broad array of phenotypic (dysmorphic), physiological, and neurological defects (the latter including moderate to severe mental retardation and autism), and represents the first described multiple congenital anomalies syndrome (6, 8–11). Although the exact disease mechanism is not yet understood, cholesterol deficiency and/or the buildup of 7-DHC are generally thought to be critical to the pathobiology of SLOS; yet, cholesterol supplementation is an incomplete and variably effective therapeutic intervention for this disease (12–18).

Recently, we reported that 7-DHC is more labile to free radical oxidation than any other known lipid (e.g., >200 times more reactive than cholesterol), and we have identified over a dozen 7-DHC-derived oxysterols generated by free radical oxidation in solution (19, 20). We have proposed that such oxysterols may be implicated in the pathogenesis of SLOS (20–22). Oxysterols are biologically active and potent molecules with a diversity of functions, both normal and pathological, in cells and tissues, including (but not limited to) the promotion of cell death and inflammation, regulation of cholesterol homeostasis and hedgehog signaling pathways, and immune system modulation (23–31).

Oxysterols derived from free radical oxidation of 7-DHC in solution have been shown to exert varied degrees of cytotoxicity depending on their structural features, leading to cellular morphological changes and induction of differential gene expression in a manner similar to that observed in Dhcr7-deficient cells (20, 21). More importantly, multiple new oxysterols have been observed in Dhcr7-deficient Neuro2a cells, SLOS human fibroblasts, and Dhcr7-null mouse brains by HPLC-MS when compared with their corresponding controls (21, 32). One of these novel oxysterols was identified as 3β,5α-dihydroxycholest-7-en-6-one (DHCEO), a product of 7-DHC free radical oxidation most likely formed from the intermediate 7-DHC-5α,6α-epoxide, which also is biologically active (21, 32). In those recent studies, several oxysterols were not fully characterized, due to the lack of sufficient quantities available from cells and mouse brains (32).

AY9944 [trans-1,4-bis(2-chlorobenzylaminomethyl) cyclohexane dihydrochloride] is a selective inhibitor of DHCR7, the same enzyme that is affected in SLOS (33, 34). Kolf-Clauw et al. (35–38) and Xu et al. (39) generated animal models of SLOS by treating rats with AY9944 or with a related DHCR7 inhibitor, BM15766; however, postnatal viability was limited. Subsequently, the AY9944-induced SLOS rat model was improved by Fliesler and coworkers, such that postnatal viability was extended to at least three months (40–42). This was necessary in order to be able to characterize the onset and progression of the biochemical, morphological, and electrophysiological features of the retinal degeneration that occurs in this model, since the rodent retina undergoes substantial development over the first several weeks of postnatal life (41, 42). It has been demonstrated that the levels of lipid hydroperoxides in retinas of AY9944-treated rats are comparable to those found in photo-damaged retinas of control rats, and that exposure of AY9944-treated rats to intense visible light greatly accelerates the formation and steady-state accumulation of such oxidized lipids in the retina, which correlates with markedly increased severity and geographic extent of the associated retinal degeneration in this model (43, 44).

Given the above, we investigated the presence, types, and amounts of 7-DHC-derived oxysterols in the AY9944-induced SLOS rat model. Herein, we report 1) the isolation and characterization of five oxysterols from the brains of AY9944-treated rats, employing HPLC-ultraviolet (UV), HPLC-MS, and 1D- and 2D-NMR; 2) the HPLC-MS-MS oxysterol profiles of AY9944-treated and age-matched control rat brain, liver, and serum; 3) the chemical synthesis of two novel, 7-DHC-derived oxysterols (4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC); and 4) quantification of four of the five oxysterols in AY9944-treated and control rat brain, liver, and serum with HPLC-MS-MS using a deuterated standard of DHCEO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Unless stated otherwise, all biochemical and analytical reagents and solvents were of the highest purity, and used as obtained from various commercial vendors. Hexanes (HPLC grade), 2-propanol (HPLC grade), and other solvents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Selenium dioxide, lead (IV) acetate, N-bromosuccinimide, benzoyl peroxide, trimethyl phosphite, and all other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., and were used without further purification. AY9944 [trans-1,4-bis(2-chlorobenzylaminomethyl) cyclohexane dihydrochloride] was prepared by custom organic synthesis (Dr. Abdul Fauq, Chemistry Core, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL) and was found to be identical in structure and purity (>99%) to an authentic sample of AY9944 previously obtained from Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, as determined by HPLC, 1H-NMR, and GC-MS. [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]Cholesterol (99% D) was purchased from Medical Isotopes, Inc. [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]7-DHC and [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]DHCEO were synthesized as reported previously (32).

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). The AY9944-induced SLOS rat model was generated as described in detail previously (41). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Buffalo VA Medical Center and conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All rats were maintained in dim cyclic light (20–40 lux, 12 h light/12 h dark) at 22–25°C and were provided cholesterol-free rodent chow (Purina Mills TestDiet, Richmond, IN) and water ad lib. At desired ages (2 to 3 months postnatal), rats were euthanized by sodium pentobarbital overdose, conforming to procedures approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association Panel of Euthanasia, and tissues were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in darkness at −80°C until ready for extraction and analysis of lipids (see below).

Isolation of oxysterols from brain tissues #8232of AY9944-treated rats

Brain tissues (∼1.5 g) of 2 or 3 month-old rats were homogenized and extracted in a similar way as described previously (32). The organic layer was dried under nitrogen, reconstituted in methylene chloride, and subjected to separation on NH2-solid phase extraction cartridge [Phenomenex, 500 mg; solvents: condition with 4 ml hexane and elution with 4 ml chloroform/2-propanol (2:1) to collect neutral lipids including oxysterols]. The eluted fraction was divided into half, and each half was subjected to separation on normal-phase Si-SPE (1 g; solvents: condition with hexane, elution with 20 ml 0.5% 2-propanol in hexane to remove the majority of cholesterol and 7-DHC, elution with 10 ml 15% 2-propanol in hexane to collect the fraction that contains oxysterols). The resulting fractions containing oxysterols were subjected to separation with reverse-phase (RP)-HPLC-UV (150 × 2 mm C18 column; 3 μm; 0.2 ml/min; elution solvent: acetonitrile-methanol, 70:30, v/v), and thus obtained HPLC fractions were subsequently separated with normal-phase (NP)-HPLC-UV (Silica 4.6 mm × 25 cm column; 5 μ; 1.0 ml/min; elution solvent: 10% 2-propanol in hexane). Pure fractions were obtained in this way and were analyzed by one dimensional (1D)- and 2D-NMR spectroscopy to characterize the oxysterol structures as described in the text (also see Supplementary Materials).

Lipid extraction from brain, liver, and serum and quantification of sterols and oxysterols

All samples were processed under dim red light. An appropriate amount of d7-DHCEO standard was added to each sample before sample processing. Brain tissues (vertical cut half brain) and liver tissues (∼100 mg cut off from the whole liver) were worked up similarly to what is described above, but without the Si-SPE procedure. Lipid extraction from serum (200 μl; each sample was spiked with 20.8 μg d7-7-DHC and 20.0 μg d7-cholesterol) was carried out in a similar procedure. Thus obtained organic layer from serum extraction was blown dry with nitrogen and was reconstituted in methanol (0.5 ml) and 1 M KOH in water (0.5 ml), and the resulting mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The hydrolyzed mixture was directly extracted with hexane (2 ml × 2), and the combined organic layers were dried under nitrogen, reconstituted in methylene chloride (200 μl), and stored at −80°C until analysis. Oxysterols in all samples were analyzed by NP-HPLC atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)-MS-MS following the previously reported method (32). NP-HPLC condition is the same as described above. For MS analysis, selective reaction monitoring (SRM) was employed to monitor the dehydration process of the ion [M+H]+ or [M+H-H2O]+ in the mass spectrometry (32). Levels of cholesterol and 7-DHC were analyzed by GC for brain and liver using cholestanol as the external standard and by GC-MS for serum using d7-cholesterol and d7-7-DHC as the internal standard. GC and GC-MS conditions are the same as we previously reported (32).

Stability of DHCEO under KOH hydrolysis condition

Control serum was used in this test, and the work-up procedure was the same as described above unless otherwise noted. Appropriate amounts of oxysterols, including 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, 7-ketocholesterol (7-kChol), and DHCEO, were added to the lipid extracts before and after hydrolysis. d7-DHCEO standard was added to each sample after hydrolysis to quantify the remaining oxysterols. Samples were analyzed with NP-HPLC-MS-MS in the same way as described above. 4α- and 4β-Hydroxy-7-DHC and 7-kChol were found to be stable under the hydrolysis condition (all recovery rates were close to 100%). The recovery rate for DHCEO, however, was only 28%.

Synthesis of 4alpha- and 4beta-hydroxy-7-DHC

For synthetic procedures and product characterization, see Supplementary Materials.

RESULTS

Characterization of five oxysterols in brain tissues of AY9944-treated rats

Prior studies from our laboratory have indicated the presence of novel 7-DHC-derived oxysterols in brains of Dhcr7-null mice, but unambiguous identification and quantification of these presumed oxysterols was impaired by the relatively limited amount of available tissues, noncharacteristic mass spectra obtained from those compounds, and the lack of authentic oxysterol standards. The vertebrate brain is highly enriched in lipids (∼40–80%, by dry wt., depending on region), of which cholesterol constitutes ∼20% of the total (45). The levels of 7-DHC and cholesterol have been examined in brain and other tissues of AY9944-treated rats, in comparison with age- and sex-matched controls: typically, 7-DHC/cholesterol ratios are ≥4/1 in brain, retina, liver, and serum by one postnatal month of AY9944 treatment, and the ratio increases thereafter (e.g., >11/1 in liver and serum by three postnatal months) (22, 40, 41, 46). Thus, brain tissues of 2 or 3 month-old AY9944-treated rats were used for oxysterol isolation to ensure substantial accumulation of 7-DHC and 7-DHC-derived oxysterols.

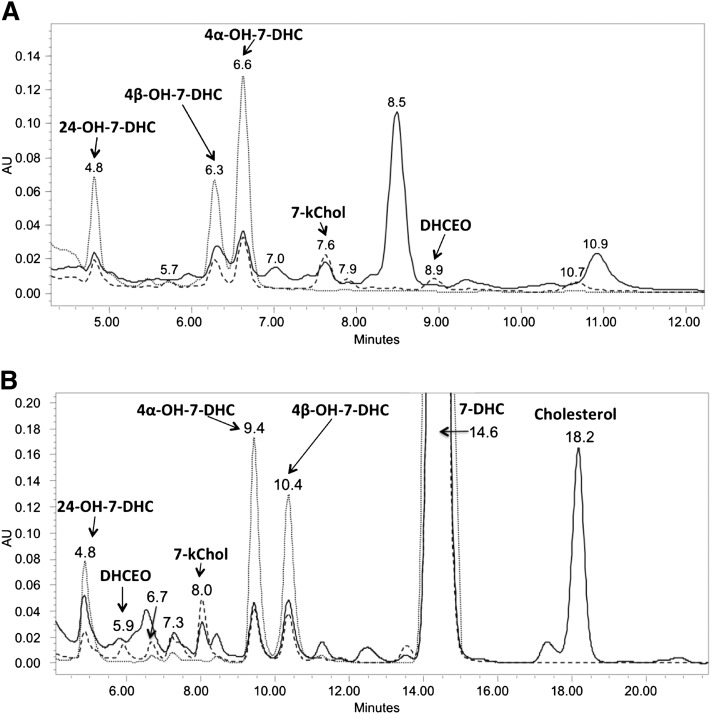

Typically, lipids extracted from rat brain were separated on NH2-SPE and Si-SPE to give fractions that contained oxysterols, and these fractions were subjected to further separation on NP- or RP-HPLC-UV (see Materials and Methods). Typical chromatograms of NP- and RP-HPLC-UV separation are shown in Fig. 1 and newly identified oxysterols are denoted therein (vide infra).

Fig.1.

A: NP-HPLC-UV (silica 4.6 mm × 25 cm column; 5 µ; 1.0 ml/min; elution solvent: 10% 2-propanol in hexanes) and (B) RP-HPLC-UV (150 × 2 mm C18 column; 3 µ; 0.2 ml/min; elution solvent: acetonitrile-methanol, 70:30, v/v) analysis of the sterol fraction extracted from AY9944-treated rat brain. Detection wavelengths: solid line, 210 nm; dashed line, 246 nm; dotted line (gray), 281 nm.

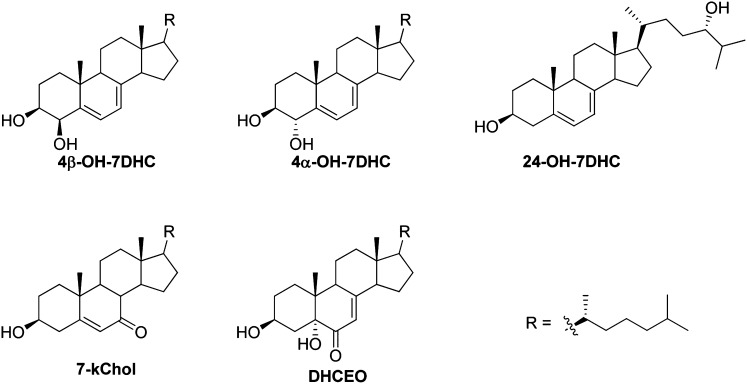

Pure fractions were isolated by combination of NP- and RP-HPLC-UVs illustrated above (see Materials and Methods), and their structures were elucidated by UV, MS, 1-dimensional (ID)- and 2D-NMR, including HSQC (heteronuclear single quantum correlation) spectroscopy, HMBC (heteronuclear multiple bond correlation) spectroscopy, COSY (correlation spectroscopy), and NOESY (nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy) (Fig. 2; see supplementary Figs. I–III, Tables I, II, and UV and NMR spectra in Supplementary Materials). As shown in Fig. 1, peaks corresponding to compounds 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC (NP-RT = 6.3 min and RP-RT = 10.4 min), 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC (NP-RT = 6.6 min and RP-RT = 9.4-min) and 24-hydroxy-7-DHC (NP-RT = 4.8 min and RP-RT = 4.8 min) have UV spectra that are similar to that of 7-DHC (see Supplementary Materials), suggesting intact conjugated diene structures in ring-B of the sterols. MS spectra suggest that these oxysterols contain one additional oxygen atom relative to 7-DHC (see Supplementary Materials).

Fig.2.

Oxysterols identified in brain tissues from AY9944-treated rats.

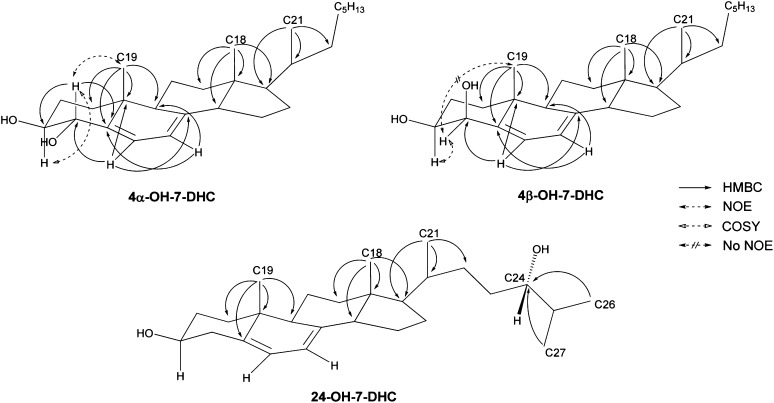

2D-NMR interpretation was carried out on these compounds similar to our previous analysis of the oxysterols that are formed from 7-DHC free radical oxidation (20). Here we show analysis of 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC as an example (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Materials). From the HSQC spectrum, correlation between each carbon and the directly connected protons can be obtained along with the odd/even number of attached protons, even though a direct 13C-NMR spectrum was not obtained due to the limited amount of isolated material. This is important in finding critical anchoring chemical shifts, such as H-4, H-6, H-7, H-18, H19, H-21 and H-26/27. Both H-18 and H-21 have strong coupling to C-17 and these correlations can be used to differentiate H-18 from H-19 as both are distinct singlets. Strong coupling between H-19 and the vinyl carbon C-5 in the HMBC spectrum and the existence of two vinyl signals in 1H-NMR are consistent with the intact diene structure in ring-B. The COSY spectrum suggests that H-3 and H-4 are coupled to each other and the HMBC spectrum support the position of the additional hydroxyl group at C-4 with the correlation between vinyl H-6 and C-4. Finally, stereochemistry was supported by the strong correlation between H-4 and H-19 in the NOESY spectrum. Coupling signals in 2-D spectra of 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC are similar to those for 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC with the exception that the correlation between H-4 and H-19 in the NOESY spectrum is absent, thus proving the β-configuration of the additional hydroxyl group at C-4 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Materials).

Fig.3.

HMBC, COSY, and NOESY correlations of selected oxysterols isolated from brain tissues of AY9944-treated rats.

The compound that correlates to 24-hydroxy-7-DHC can be elucidated in a similar way (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Materials). The key difference in this analysis is that there is no correlation between vinyl proton signals and the carbon (a methine group) with the additional hydroxyl group. H-26 and H-27 are distinct paired doublets at δ 0.90 and 0.93 ppm of the 1H-NMR spectrum. In the HMBC spectrum, both H-26 and H-27 have strong coupling to the methine group that is connected to the new hydroxyl group, indicating the additional hydroxyl group is at C-24. We have no direct evidence regarding configuration of the stereogenic center at C-24. However, since this oxysterol is apparently a product of enzymatic oxidation of 7-DHC by cytochrome P450 46A1 (CYP46A1), and since it is known that CYP46A1 catalyzes the oxidation of cholesterol to 24(S)-hydroxy-cholesterol, we tentatively assign the stereochemical configuration of C-24 to be “S” (47, 48).

Elucidation of the structure of 7-kChol (NP-RT = 7.6 min and RP-RT = 8.0 min) was straightforward. The large downfield chemical shift of the quaternary vinyl carbon (δ 165 ppm) in the 13C-NMR spectrum and its coupling to H-19 in the HMBC spectrum suggests an “enone” structure at C-5, C-6, and C-7 of ring-B. More importantly, a side-by-side comparison of the 1H-NMR spectra with a synthesized standard of 7-kChol unequivocally confirms its structure (see supplementary Fig. I).

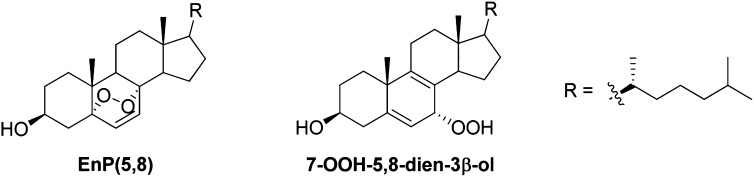

In addition, the peak at RT = 7.3 min in Fig. 1B (RT = 5.9 min in NP-HPLC-UV, Fig. 1A) was confirmed to be one of the 7-DHC photooxidation products, 5α,8α-epidioxy-cholest-6-en-3β-ol [EnP(5,8)] (Fig. 4), by comparing the mass spectrum, 1H-NMR and HSQC NMR spectra with those of a synthetic standard (49, 50). However, formation of EnP(5,8) can be minimized (but cannot be completely avoided) when the brain samples were processed under dim red light, suggesting that this oxysterol is an ex vivo oxidation product. The observation of d7-EnP(5,8) when samples were processed with an internal standard of d7-7-DHC further supports this notion (vide infra).

Fig.4.

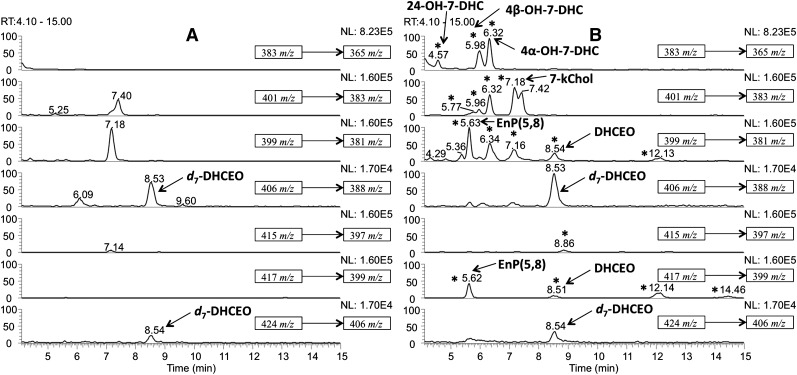

The oxysterol profiles of control and AY9944-treated rat brains were subsequently analyzed by an HPLC-APCI-MS-MS method as we have described in detail previously (20, 21, 32). Briefly, the dehydration process of the ion [M+H]+ (to [M+H-H2O]+) or [M+H-H2O]+ (to [M+H-2H2O]+) in the mass spectrometry was monitored by SRM. As expected, new oxysterol peaks were observed in the chromatogram of the AY9944-treated rat brains when compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 5A, B). The chromatograms are similar to those observed for Dhcr7-null mouse brain reported previously (32). The peak corresponding to the oxysterol DHCEO can be immediately identified, as it coelutes with and has the same MS pattern as that of the synthetic [25,26,26,26,27,27,27-d7]DHCEO standard. Newly identified oxysterols as discussed above were assigned in the AY9944-treated rat brain chromatogram by comparing the mass spectra and RTs with those of the isolated standards. It is worth noting that DHCEO has been characterized previously in lipid extracts from Dhcr7-deficient cells and Dhcr7-null mouse brains in a similar way, and the existing data suggest that it is formed by free radical oxidation of 7-DHC (32). It was also established that DHCEO is a biomarker for 7-DHC oxidation both in cultured cells and in vivo (32).

Fig.5.

NP-HPLC-APCI-MS-MS (silica 4.6 mm × 25 cm column; 5 μ; 1.0 ml/min; elution solvent: 10% 2-propanol in hexane) analysis of the oxysterols from brains of 2 month-old (A) control and (B) AY9944-treated rats. New peaks observed in AY9944-treated rats relative to control rats are indicated by asterisks (*).

Oxysterol profiles of control and AY9944-treated rat liver and serum

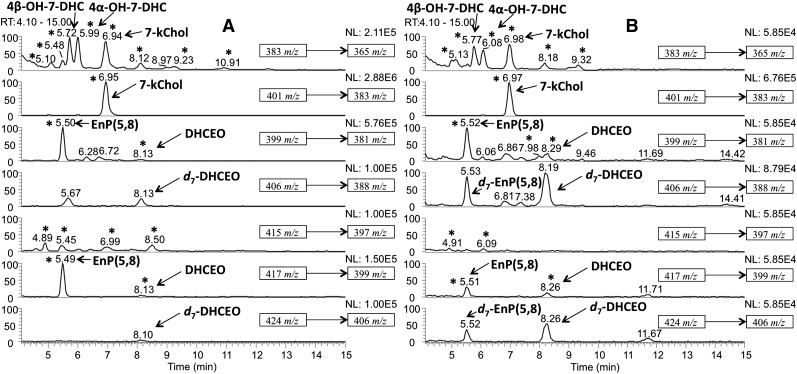

Oxysterol components of rat liver and serum were analyzed using the HPLC-MS-MS method described above and peaks in AY9944-treated samples were assigned by comparing the MS spectra and retention time of each peak with those of the newly identified oxysterols (Fig. 6). When the serum samples were processed by Folch extraction followed by NH2-SPE separation without KOH hydrolysis, none of the new oxysterols were observed at a significant level in sera from AY9944-treated rats relative to corresponding controls, suggesting that majority of 7-DHC-derived oxysterols exist as FA esters in rat blood. However, DHCEO, 7-kChol, 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC were observed both in AY9944-treated rat liver and in KOH-hydrolyzed serum, whereas 24-hydroxy-7-DHC was not identified in these samples (Fig. 6).

Fig.6.

NP-HPLC-APCI-MS-MS chromatograms of (A) oxysterols from liver and (B) KOH-hydrolyzed serum from 2 month-old AY9944-treated rats.

It is worth noting that serum samples were processed in the presence of an internal standard of chemically synthesized d7-7-DHC under conditions that precluded exposure to visible or UV light (dim red light or darkness); the observation of the presence of d7-EnP(5,8) provides further evidence for the ex vivo formation of EnP(5,8) in these specimens (i.e., formation of EnP(5,8) cannot be completely avoided even under dim red light).

Synthesis of 4alpha- and 4beta-hydroxy-7-DHC

4α- and 4β-Hydroxy-cholesterol were prepared by previously established procedures (51, 52) and their diacetate esters were subsequently converted to 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC diacetate esters via bromination with N-bromosuccinimide and benzoyl peroxide followed by elimination of hydrogen bromide via refluxing with trimethyl phosphite in xylene (see Supplementary Materials) (53, 54). Upon LiAlH4 reduction, 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC was readily purified by flash column chromatography and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC was purified by reaction with 4-phenyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione, separation on silica column chromatography, and another LiAlH4 reduction (54).

1D- and 2D-NMR spectra of the synthesized 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC are consistent with those of the isolated oxysterols, providing further support for the oxysterol structures assigned (see supplementary Figs. II, III).

Quantification of DHCEO, 7-keto, and 4alpha- and 4beta-hydroxy-7-DHC in 2 month-old control and #8232AY9944-treated rat brain, liver, and serum

Quantification of the above characterized oxysterols in tissues of 2-month old rats was carried out via the standard HPLC-APCI-MS-MS method using d7-DHCEO as an internal standard. Response factors of different oxysterols relative to d7-DHCEO were determined by comparing the MS responses of the synthetic standards with d7-DHCEO. The levels of 24-hydroxy-7-DHC were not determined due to lack of an authentic synthetic standard.

The quantification results are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Quantification of known oxysterols and sterols in tissues and fluids of 2 month-old control and AY9944-treated ratsa

| Brain | Liver | Serum | ||||

| mg tissue | mg tissue | ml serum | ||||

| Ctrl | AY9944 | Ctrl | AY9944 | Ctrl | AY9944 | |

| 4α-Hydroxy-7-DHC (ng) | 0 | 43 ± 11 | 0 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 0 | – b |

| 4β-Hydroxy-7-DHC (ng) | 0 | 48 ± 12 | 0 | 7.1 ± 3.2 | 0 | – b |

| 7-kChol (ng) | 0.69 ± 0.07 | 21 ± 7 | 0.23 ± 0.22 | 11 ± 4 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | – b |

| DHCEO (ng) | 0.015 ± 0.03 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0 | 0.43 ± 0.08 | 0 | 31 ± 7 |

| Chol (μg) | 12.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 297 ± 43 | 4.0 ± 1.1 |

| 7-DHC (μg) | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 0 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0 | 71.2 ± 7.5 |

| 7-DHC/Chol | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 0 | 20 ± 3 | 0 | 18 ± 6 |

P < 0.005 for all AY9944-treated samples relative to corresponding controls; n = 4 for brain tissues; n = 8 for liver; n = 8 for serum.

Inasmuch as the internal standard d7-DHCEO decomposes under the hydrolysis condition, levels of these oxysterols were not determined in rat serum (see Materials and Methods).

First, it should be noted that the total level of neutral “parent” sterols (i.e., cholesterol and 7-DHC) in sera from AY9944-treated animals (∼75.2 μg/ml) was about 4-fold lower than in control sera (297 μg/ml), which is consistent with the well-known sterol-lowering effects of AY9944 (33–35, 40, 41). Also, 7-DHC was not found in detectable amounts in liver or serum from control rats, and was present only in extremely small amounts in control brains (nearly 60-fold less than the levels of cholesterol). By contrast, 7-DHC was the dominant sterol in tissues from AY9944-treated rats, present at ∼20-fold molar excess over cholesterol in serum and liver. Interestingly, whereas 7-kChol was the dominant oxysterol detected in serum and liver in AY9944-treated rats (also see Fig. 6), present in approximately 2-fold the amounts of either 4α- or 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, the reverse was found to be true for brains of AY9944-treated rats (also see Fig. 5), where the latter two oxysterols were the dominant oxysterol species detected (of the oxysterols quantified). In fact, on a per-milligram of tissue basis, the levels of 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC were 7- to 10-fold greater in brain than in liver in AY9944-treated rats. DHCEO also was not found in control liver or serum, and was present only in very low amounts in control brain (>270-fold less than the levels found in AY9944-treated brain samples).

DISCUSSION

In a free radical oxidation reaction in solution, 7-DHC oxidizes nearly 200 times faster than cholesterol (19), generating a large number of novel oxysterols (20). Due to this large difference in reactivity toward oxidation, high levels of oxysterols would be expected to form in tissues and fluids of patients with SLOS, where levels of 7-DHC are also high. Elevated levels of novel 7-DHC-derived oxysterols have been reported in Dhcr7-deficient cells and in tissues of Dhcr7-null mice, but only one of these oxysterols, DHCEO, was identified in cultured cells and in vivo in biological tissues (21, 32). A lack of well-characterized standard compounds to be used for comparison is a major limitation in identifying the other oxysterols shown to be present in vivo.

The AY9944-treated rat has the same biochemical hallmarks as the Dhcr7-null mouse, namely high levels of 7-DHC and low levels of cholesterol, and has been used to study the phenotype and pathogenesis of SLOS, such as embryological dysgenesis, skeletal defects, morphological abnormalities, and the onset and progression of retinal degeneration (35–37, 40–42, 55–57). The improvements to the AY9944-treated SLOS rat model developed by Fliesler and coworkers (40–42) greatly increased the lifespan of these rats while maintaining the high 7-DHC:cholesterol ratio. An advantage of this latter model is that these AY9944-treated rats can grow to adult stage and thus generate large amounts of tissues for oxysterol isolation and analysis.

Herein, we have provided compelling evidence for the formation and steady-state accumulation of five oxysterols (see Fig. 2), including the novel sterols 4α- and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC and 24-hydroxy-7-DHC in brain and/or in liver and serum of rats, where Dhcr7 activity was blocked by the inhibitor AY9944. Even though oxysterols can be identified by derivatization coupled with MS analysis, noncharacteristic loss-of-water ions are most frequently observed (58). On the other hand, NMR analysis usually provides an unequivocal method for unknown identification. Although DHCEO has been previously identified in Dhcr7-deficient cultured cells and in tissues from Dhcr7-null mice, 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC, 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, 24-hydroxy-7-DHC, and 7-kChol were characterized in a SLOS rodent model for the first time in this report. Notably, with the exception of 7-kChol (which can arise directly via oxidation of cholesterol), these oxysterols were below the limits of detection in tissues from age-matched control rats (DHCEO in control brain tissues being close to the limit of detection). Our analyses point to 7-DHC as the parent sterol from which these oxysterols arise, inasmuch as 7-DHC is the major neutral sterol found in tissues from AY9944-treated rats. It is present in ∼5–20-fold molar excess over cholesterol in those tissues (see Table 1), and is >200 times more readily oxidized than is cholesterol (19), whereas the levels of 7-DHC in control tissues are almost negligible.

Evidence supports the notion that DHCEO can be formed from 5α,6α-epoxycholest-7-en-3β-ol, a product of 7-DHC free radical oxidation, in human fibroblasts and Neuro2a cells (32). In the same studies, DHCEO was established as a biomarker for 7-DHC oxidation in cells and in vivo, and the compound can exert biological activities itself, being cytotoxic and inducing important changes in genes like Ki67, Erg1, Hmgcr, Dhcr7, and SQS in Neuro2a cells (21). An antioxidant was reported to be effective in suppressing the level of the DHCEO in SLOS human fibroblasts, indicating a potential alternative or supplementary therapeutic treatment for the syndrome (32).

4α-Hydroxy-7-DHC, 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, and 24-hydroxy-7-DHC are novel oxysterols that have not been previously reported in SLOS cells or tissues. 24-Hydroxy-7-DHC is probably formed from 7-DHC enzymatically by CYP46A1, inasmuch as 24(S)-hydroxy-cholesterol is a metabolite of cholesterol. This observation is surprising, inasmuch as one previous report suggests that CYP46-expressing HEK293 cells had no significant activity toward 7-DHC, and no side-chain hydroxylated 7-DHC was observed in the plasma of SLOS patients (59). This apparent difference warrants further investigation on the reactivity of 7-DHC as a substrate for CYP46A1. One the other hand, the origins of 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC are unclear. It has been reported that CYP3A4 converts cholesterol to 4β-hydroxy-cholesterol, but not 4α-hydroxy-cholesterol (60, 61), and studies suggest that 4α-hydroxy-cholesterol is formed from either free radical oxidation of cholesterol or by an enzyme that is not influenced by P450-inducing drugs such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and ursodeoxycholic acid (60). 4α-Hydroxy-cholesterol and 4β-hydroxy-cholesterol were also observed at approximately equal concentrations in oxidized LDL and in human atherosclerotic tissues, further indicating that they can be formed by autoxidation (62). In our previous studies on free radical oxidation of 7-DHC in solution, however, neither 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC nor 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC were isolated as products, even though there are potential free radical mechanisms that anticipate their formation (20). Thus, further investigation is needed to elucidate the origin of 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC and 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC in vivo.

7-KChol is a known oxysterol that can exert cytotoxicity, inhibit growth, induce apoptosis and inflammation, and may play an important role in choroidal neovascularization (30, 63–67). 7-KChol is widely considered a free radical oxidation product of cholesterol through decomposition of 7α-OOH-Chol and 7β-OOH-Chol or oxidation of 7α-hydroxy-cholesterol and 7β-hydroxy-cholesterol (23–25, 68–71). An enzymatic origin of 7-kChol has also been suggested (25, 72). 7-KChol is one of the most abundant oxysterols in atherosclerotic lesions and it is greatly elevated in photodamaged rat retina (71). However, formation of 7-kChol in AY9944-treated rats is quite unusual, inasmuch as levels of cholesterol (the only known precursor to 7-kChol) are greatly diminished, relative to controls. In brain and liver, respectively, levels of 7-kChol in AY9944-treated rats are 30 and 50 times those in the corresponding tissues of control rats, whereas levels of cholesterol are 1/9 and 1/20 of those in controls, respectively. If all of the 7-kChol in tissues from AY9944-treated animals was formed from cholesterol, it would mean that at least 1.5% and 10%, respectively, of total cholesterol in these tissues was oxidized. This seems highly unlikely, considering the fact that 7-DHC is >200 times more oxidizable than is cholesterol (19). Thus, it appears that the majority of the 7-kChol found in tissues from AY9944-treated animals was derived from 7-DHC. Because 7-kChol is not a known product of 7-DHC free radical oxidation in solution (20), it is reasonable to speculate that its origin in vivo is enzymatic. Indeed, in another recent study, we have demonstrated that conversion of 7-DHC to 7-kChol can be catalyzed by human liver microsomes and by P450 CYP7A1 (73). The detailed mechanism of this transformation is discussed in that report (73).

The finding of EnP(5,8) as an ex vivo photooxidation product of 7-DHC suggests that previous reports by De Fabiani et al. (74) on the observation of 7-DHC photooxidation products, including EnP(5,8) and cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3β-ol (a known decomposition product of the primary photooxidation product, 7-hydroperoxy-cholesta-5,8-dien-3β-ol) (Fig. 4) (49, 50), in plasma of a SLOS patient may be based on ex vivo artifact. This finding also emphasizes the importance of handling samples from SLOS patients under dark or dim red-light conditions and/or under an atmosphere of inert gas. As 7-DHC photooxidation yields a hydroperoxide and an endoperoxide as the primary products (Fig. 4) (49, 50), reaction of these peroxides with transition metal ions, such as those of iron and copper, can in turn promote the formation of secondary free radical oxidation products derived therefrom.

To the extent that the AY9944-treated rat is a faithful model of SLOS, these findings may have a bearing on the pathobiological mechanism underlying this human disease. First, it is already well established that oxysterols can be cytotoxic as well as being potent regulators of various biochemical and signal transduction pathways (23–31). More importantly, we have shown that certain oxysterols derived from 7-DHC can be extraordinarily cytotoxic (21). For example, two such oxysterols, 6α-hydroxy- and 6β-hydroxy-5,8-endoperoxy-cholest-7-en-3β-ol (compounds 2a and 2b in ref. 20 and 21), were found to be 5-fold more toxic than was 7-kChol to Neuro2a cells in culture, whereas DHCEO (compound 10 in ref. 20 and 21) was about twice as toxic as 7-kChol. Notably, 7-kChol is thought to be one of the more cytotoxic oxysterols found in biological systems, and has been implicated in several prominent diseases, including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, and, most recently, age-related macular degeneration (23–31, 67). The formation and steady-state accumulation of such potentially cytotoxic and biologically active molecules, as well as the conveyance of those molecules in the bloodstream to virtually all cells and tissues throughout the body, renders essentially every tissue in the body prone to the deleterious effects of these oxysterols. The pleiotropic effects of such oxysterols is consistent with the broad spectrum of phenotypic, physiological, and neurological abnormalities observed in SLOS and related diseases involving defective cholesterol biosynthesis (7–9, 75). However, a more definitive correlation between 7-DHC-derived oxysterols and disease severity in SLOS awaits the outcome of well-controlled human subject studies, where uniform conditions are employed to ensure tissue or fluid sample integrity, minimal ex vivo oxidation, minimum time from tissue harvesting to analysis, and consistent, rigorous, analytical approaches to detection and quantification of sterols and oxysterols.

In summary, five oxysterols were unequivocally identified in tissues and fluids of AY9944-treated rats by a combination of UV, HPLC-MS, and 1D- and 2D-NMR. Three of these oxysterols, 4α-hydroxy-7-DHC, 4β-hydroxy-7-DHC, and 24-hydroxy-7-DHC, are novel (heretofore not reported) compounds. Identification of DHCEO in all specimens derived from AY9944-treated rats supports our previous establishment of DHCEO as a biomarker of 7-DHC oxidation in vivo. In addition, the levels of 7-kChol that form and accumulate in AY9944-treated rats are relatively large, even though the levels of cholesterol are substantially lower than normal, suggesting that 7-DHC is its biochemical precursor. Elevated levels of oxysterols in AY9944-treated rats suggest that these oxysterols may play important roles in the pathological features associated with this animal model of SLOS and, by inference, in SLOS itself.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joyce Young for technical assistance during the initial phase of this work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- APCI

- atmospheric pressure chemical ionization

- Chol

- cholesterol

- COSY

- correlation spectroscopy

- CYP46A1

- cytochrome P450 46A1 (cholesterol 24-hydroxylase)

- 1D

- one dimensional

- 7-DHC

- 7-dehydrocholesterol

- DHCEO

- 3β,5α-dihydroxycholest-7-en-6-one

- Dhcr7 or DHCR7

- 3β-hydroxysterol-Δ7-reductase

- EnP(5,8)

- 5α,8α-epidioxy-cholest-6-en-3β-ol

- HMBC

- heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- 7-kChol

- 7-ketocholesterol

- NOESY

- nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- NP

- normal-phase

- RP

- reverse-phase

- SLOS

- Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

- SRM

- selective reaction monitoring

- UV

- ultraviolet

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service (National Institutes of Health) Grants ES-013125 (N.A.P.), HD-064727 (N.A.P.), and EY-007361 (S.J.F.), National Science Foundation Grants CHE 0717067 (N.A.P.), and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (S.J.F.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data

REFERENCES

- 1.Irons M., Elias E. R., Salen G., Tint G. S., Batta A. K. 1993. Defective cholesterol biosynthesis in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Lancet. 341: 1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tint G. S., Irons M., Elias E. R., Batta A. K., Frieden R., Chen T. S., Salen G. 1994. Defective cholesterol biosynthesis associated with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 330: 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzky B. U., Moebius F. F., Asaoka H., Waage-Baudet H., Xu L., Xu G., Maeda N., Kluckman K., Hiller S., Yu H., et al. 2001. 7-Dehydrocholesterol-dependent proteolysis of HMG-CoA reductase suppresses sterol biosynthesis in a mouse model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz/RSH syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 108: 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krakowiak P. A., Nwokoro N. A., Wassif C. A., Battaile K. P., Nowaczyk M. J., Connor W. E., Maslen C., Steiner R. D., Porter F. D. 2000. Mutation analysis and description of sixteen RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome patients: polymerase chain reaction-based assays to simplify genotyping. Am. J. Med. Genet. 94: 214–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waterham H. R. 2002. Inherited disorders of cholesterol biosynthesis. Clin. Genet. 61: 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sikora D., Pettit-Kekel K., Penfield J., Merkens L., Steiner R. 2006. The near universal presence of autism spectrum disorders in children with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 140: 1511–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter F. D., Herman G. E. 2011. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 52: 6–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley R. I., Hennekam R. C. 2000. The Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 37: 321–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter F. D. 2003. Human malformation syndromes due to inborn errors of cholesterol synthesis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 15: 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukelis I., Porter F. D., Zimmerman A. W., Tierney E. 2007. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 164: 1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charman C. R., Ryan A., Tyrrell R. M., Pearse A. D., Arlett C. F., Kurwa H. A., Shortland G., Anstey A. 1998. Photosensitivity associated with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Br. J. Dermatol. 138: 885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irons M., Elias E. R., Tint G. S., Salen G., Frieden R., Buie T. M., Ampola M. 1994. Abnormal cholesterol metabolism in the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: report of clinical and biochemical findings in four patients and treatment in one patient. Am. J. Med. Genet. 50: 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias E. R., Irons M. B., Hurley A. D., Tint G. S., Salen G. 1997. Clinical effects of cholesterol supplementation in six patients with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS). Am. J. Med. Genet. 68: 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irons M., Elias E. R., Abuelo D., Bull M. J., Greene C. L., Johnson V. P., Keppen L., Schanen C., Tint G. S., Salen G. 1997. Treatment of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: results of a multicenter trial. Am. J. Med. Genet. 68: 311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starck L., Lovgren-Sandblom A., Bjorkhem I. 2002. Cholesterol treatment forever? The first Scandinavian trial of cholesterol supplementation in the cholesterol-synthesis defect Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 252: 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikora D. M., Ruggiero M., Petit-Kekel K., Merkens L. S., Connor W. E., Steiner R. D. 2004. Cholesterol supplementation does not improve developmental progress in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Pediatr. 144: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas D., Garbade S. F., Vohwinkel C., Muschol N., Trefz F. K., Penzien J. M., Zschocke J., Hoffmann G. F., Burgard P. 2007. Effects of cholesterol and simvastatin treatment in patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS). J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30: 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tierney E., Conley S. K., Goodwin H., Porter F. D. 2010. Analysis of short-term behavioral effects of dietary cholesterol supplementation in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 152A: 91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L., Davis T. A., Porter N. A. 2009. Rate constants for peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and sterols in solution and in liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131: 13037–13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu L., Korade Z., Porter N. A. 2010. Oxysterols from free radical chain oxidation of 7-dehydrocholesterol: product and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132: 2222–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korade Z., Xu L., Shelton R., Porter N. A. 2010. Biological activities of 7-dehydrocholesterol-derived oxysterols: implications for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3259–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fliesler S. J. 2010. Retinal degeneration in a rat model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: thinking beyond cholesterol deficiency. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 664: 481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith L. L., Johnson B. H. 1989. Biological activities of oxysterols. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 7: 285–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown A. J., Jessup W. 1999. Oxysterols and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 142: 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroepfer G. J., Jr 2000. Oxysterols: modulators of cholesterol metabolism and other processes. Physiol. Rev. 80: 361–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javitt N. B. 2007. Oxysterols: functional significance in fetal development and the maintenance of normal retinal function. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 18: 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Javitt N. B. 2008. Oxysterols: novel biologic roles for the 21st century. Steroids. 73: 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Björkhem I., Cedazo-Minguez A., Leoni V., Meaney S. 2009. Oxysterols and neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Aspects Med. 30: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown A. J., Jessup W. 2009. Oxysterols: sources, cellular storage and metabolism, and new insights into their roles in cholesterol homeostasis. Mol. Aspects Med. 30: 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vejux A., Lizard G. 2009. Cytotoxic effects of oxysterols associated with human diseases: induction of cell death (apoptosis and/or oncosis), oxidative and inflammatory activities, and phospholipidosis. Mol. Aspects Med. 30: 153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olkkonen V. M., Hynynen R. 2009. Interactions of oxysterols with membranes and proteins. Mol. Aspects Med. 30: 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L., Korade Z., Rosado D. A., Liu W., Lamberson C. R., Porter N. A. 2011. An oxysterol biomarker for 7-dehydrocholesterol oxidation in cell/mouse models for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 52: 1222–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chappel C., Dubuc D., Dvornik D., Givner M., Humber L., Kraml M., Voith K., Gaudry R. 1964. An inhibitor of cholesterol biosynthesis. Nature 201: 497–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Givner M. L., Dvornik D. 1965. Agents affecting lipid metabolism–XV. Biochemical studies with the cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor AY-9944 in young and mature rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 14: 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolf-Clauw M., Chevy F., Wolf C., Siliart B., Citadelle D., Roux C. 1996. Inhibition of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase by the teratogen AY9944: a rat model for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Teratology. 54: 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf C., Chevy F., Pham J., Kolf-Clauw M., Citadelle D., Mulliez N., Roux C. 1996. Changes in serum sterols of rats treated with 7-dehydrocholesterol-delta 7-reductase inhibitors: comparison to levels in humans with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 37: 1325–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolf-Clauw M., Chevy F., Ponsart C. 1998. Abnormal cholesterol biosynthesis as in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome disrupts normal skeletal development in the rat. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 131: 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolf-Clauw M., Chevy F., Siliart B., Wolf C., Mulliez N., Roux C. 1997. Cholesterol biosynthesis inhibited by BM15.766 induces holoprosencephaly in the rat. Teratology. 56: 188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu G., Salen G., Shefer S., Ness G. C., Chen T. S., Zhao Z., Tint G. S. 1995. Reproducing abnormal cholesterol biosynthesis as seen in the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome by inhibiting the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to cholesterol in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 95: 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fliesler S. J., Richards M. J., Miller C., Peachey N. S. 1999. Marked alteration of sterol metabolism and composition without compromising retinal development or function. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40: 1792–1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fliesler S. J., Peachey N. S., Richards M. J., Nagel B. A., Vaughan D. K. 2004. Retinal degeneration in a rodent model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: electrophysiologic, biochemical, and morphologic features. Arch. Ophthalmol. 122: 1190–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fliesler S. J., Vaughan D. K., Jenewein E. C., Richards M. J., Nagel B. A., Peachey N. S. 2007. Partial rescue of retinal function and sterol steady-state in a rat model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Pediatr. Res. 61: 273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richards M. J., Nagel B. A., Fliesler S. J. 2006. Lipid hydroperoxide formation in the retina: correlation with retinal degeneration and light damage in a rat model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Exp. Eye Res. 82: 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaughan D. K., Peachey N. S., Richards M. J., Buchan B., Fliesler S. J. 2006. Light-induced exacerbation of retinal degeneration in a rat model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Exp. Eye Res. 82: 496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chavko M., Nemoto E. M., Melick J. A. 1993. Regional lipid composition in the rat brain. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 18: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fliesler S. J., Bretillon L. 2010. The ins and outs of cholesterol in the vertebrate retina. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3399–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lund E. G., Guileyardo J. M., Russell D. W. 1999. cDNA cloning of cholesterol 24-hydroxylase, a mediator of cholesterol homeostasis in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 7238–7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell D. W. 2000. Oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1529: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albro P. W., Corbett J. T., Schroeder J. L. 1994. Doubly allylic hydroperoxide formed in the reaction between sterol 5,7-dienes and singlet oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 60: 310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albro P. W., Bilski P., Corbett J. T., Schroeder J. L., Chignell C. F. 1997. Photochemical reactions and phototoxicity of sterols: novel self-perpetuating mechanism for lipid photooxidation. Photochem. Photobiol. 66: 316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fieser L., Stevenson R. 1954. Cholesterol and companions. IX. Oxidation of Δ5-cholestene-3-one with lead tetraacetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76: 1728–1733. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenheim O., Starling W. W. 1937. The action of selenium dioxide on sterols and bile acids. Part III. Cholesterol. J. Chem. Soc. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelc B. 1974. 4alpha-Hydroxycholecalciferol and an attempted synthesis of its 4-beta-hydroxy-epimer. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1436–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gill H. S., Londowski J. M., Corradino R. A., Zinsmeister A. R., Kumar R. 1988. The synthesis and biological activity of 25-hydroxy-26,27-dimethylvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxy-26,27-dimethylvitamin D3: highly potent novel analogs of vitamin D3. J. Steroid Biochem. 31: 147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roux C., Horvath C., Dupuis R. 1979. Teratogenic action and embryo lethality of AY 9944R. Prevention by a hypercholesterolemia-provoking diet. Teratology. 19: 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gofflot F., Kolf-Clauw M., Clotman F., Roux C., Picard J. J. 1999. Absence of ventral cell populations in the developing brain in a rat model of the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 87: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roux C., Dupuis R., Horvath C., Talbot J. N. 1980. Teratogenic effect of an inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis (AY 9944) in rats: correlation with maternal cholesterolemia. J. Nutr. 110: 2310–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pulfer M. K., Murphy R. C. 2004. Formation of biologically active oxysterols during ozonolysis of cholesterol present in lung surfactant. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 26331–26338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Björkhem I., Starck L., Andersson U., Lutjohann D., von Bahr S., Pikuleva I., Babiker A., Diczfalusy U. 2001. Oxysterols in the circulation of patients with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: abnormal levels of 24S- and 27-hydroxycholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 42: 366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bodin K., Bretillon L., Aden Y., Bertilsson L., Broome U., Einarsson C., Diczfalusy U. 2001. Antiepileptic drugs increase plasma levels of 4beta-hydroxycholesterol in humans: evidence for involvement of cytochrome p450 3A4. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 38685–38689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bodin K., Andersson U., Rystedt E., Ellis E., Norlin M., Pikuleva I., Eggertsen G., Bjorkhem I., Diczfalusy U. 2002. Metabolism of 4 beta-hydroxycholesterol in humans. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 31534–31540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breuer O., Dzeletovic S., Lund E., Diczfalusy U. 1996. The oxysterols cholest-5-ene-3 beta,4 alpha-diol, cholest-5-ene-3 beta,4 beta-diol and cholestane-3 beta,5 alpha,6 alpha-triol are formed during in vitro oxidation of low density lipoprotein, and are present in human atherosclerotic plaques. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1302: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. 1974. Suppression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity and inhibition of growth of human fibroblasts by 7-ketocholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 249: 7306–7314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hughes H., Mathews B., Lenz M. L., Guyton J. R. 1994. Cytotoxicity of oxidized LDL to porcine aortic smooth muscle cells is associated with the oxysterols 7-ketocholesterol and 7-hydroxycholesterol. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14: 1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vejux A., Malvitte L., Lizard G. 2008. Side effects of oxysterols: cytotoxicity, oxidation, inflammation, and phospholipidosis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 41: 545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moreira E. F., Larrayoz I. M., Lee J. W., Rodriguez I. R. 2009. 7-Ketocholesterol is present in lipid deposits in the primate retina: potential implication in the induction of VEGF and CNV formation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50: 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodriguez I. R., Larrayoz I. M. 2010. Cholesterol oxidation in the retina: implications of 7KCh formation in chronic inflammation and age-related macular degeneration. J. Lipid Res. 51: 2847–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith L. L. 1987. Cholesterol autoxidation 1981–1986. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 44: 87–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown A. J., Leong S. L., Dean R. T., Jessup W. 1997. 7-Hydroperoxycholesterol and its products in oxidized low density lipoprotein and human atherosclerotic plaque. J. Lipid Res. 38: 1730–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murphy R. C., Johnson K. M. 2008. Cholesterol, reactive oxygen species, and the formation of biologically active mediators. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 15521–15525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodriguez I. R., Fliesler S. J. 2009. Photodamage generates 7-keto- and 7-hydroxycholesterol in the rat retina via a free radical-mediated mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 85: 1116–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Song W., Pierce W. M., Saeki Y., Redinger R. N., Prough R. A. 1996. Endogenous 7-oxocholesterol is an enzymatic product: characterization of 7 alpha-hydroxycholesterol dehydrogenase activity of hamster liver microsomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 328: 272–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shinkyo R., Xu L., Tallman K. A., Cheng Q., Porter N. A., Guengerich F. P. 2011. Conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to 7-ketocholesterol is catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 7A1 and occurs by direct oxidation without an epoxide intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. Epub ahead of print . August 3, 2011; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282434. PubMed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Fabiani E., Caruso D., Cavaleri M., Galli Kienle M., Galli G. 1996. Cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3 beta-ol found in plasma of patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome indicates formation of sterol hydroperoxide. J. Lipid Res. 37: 2280–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelley R. I. 2000. Inborn errors of cholesterol biosynthesis. Adv. Pediatr. 47: 1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.