Abstract

The 70-kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp70s) function as molecular chaperones through the allosteric coupling of their nucleotide- and substrate-binding domains, the structures of which are highly conserved. In contrast, the roles of the poorly structured, variable length C-terminal regions present on Hsp70s remain unclear. In many eukaryotic Hsp70s, the extreme C-terminal EEVD tetrapeptide sequence associates with co-chaperones via binding to tetratricopeptide repeat domains. It is not known whether this is the only function for this region in eukaryotic Hsp70s and what roles this region performs in Hsp70s that do not form complexes with tetratricopeptide repeat domains. We compared C-terminal sequences of 730 Hsp70 family members and identified a novel conservation pattern in a diverse subset of 165 bacterial and organellar Hsp70s. Mutation of conserved C-terminal sequence in DnaK, the predominant Hsp70 in Escherichia coli, results in significant impairment of its protein refolding activity in vitro without affecting interdomain allostery, interaction with co-chaperones DnaJ and GrpE, or the binding of a peptide substrate, defying classical explanations for the chaperoning mechanism of Hsp70. Moreover, mutation of specific conserved sites within the DnaK C terminus reduces the capacity of the cell to withstand stresses on protein folding caused by elevated temperature or the absence of other chaperones. These features of the C-terminal region support a model in which it acts as a disordered tether linked to a conserved, weak substrate-binding motif and that this enhances chaperone function by transiently interacting with folding clients.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, Heat Shock Protein, Intrinsically Disordered Proteins, Molecular Chaperone, Protein Folding, Stress Response, DnaK, Hsp70

Introduction

The ubiquitously distributed Hsp70 family of molecular chaperones shepherd newly synthesized polypeptide chains, protect cells from stress-induced protein aggregation, assist in protein translocation across membranes, and regulate assembly and disassembly of macromolecular complexes. These physiological functions are accomplished by a two-domain allosteric mechanism in which cycles of ATP binding and hydrolysis in the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain (NBD)2 control the binding and release of hydrophobic polypeptide segments in the substrate-binding domain (SBD) (1–3). Although we have gained an increasingly detailed picture of this allosteric transition in Hsp70 chaperones and modes of substrate interaction (4–7), it is striking that there is much less known about the function of the extreme C-terminal unstructured region (Fig. 1). Binding of the C-terminal region of mammalian Hsc70 to substrate was suggested in earlier work (8, 9), and more recently, the C-terminal segment of eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s was found to contain a conserved tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain interaction motif that mediates binding with Chip, Hip, or Hop co-chaperones that facilitate the assembly of a variety of Hsp70 complexes (3). Even though bacteria lack homologs of these Hsp70-interacting TPR domain proteins, many, including the extensively characterized E. coli Hsp70 DnaK, have a disordered C-terminal extension of similar length to that in eukaryotes.

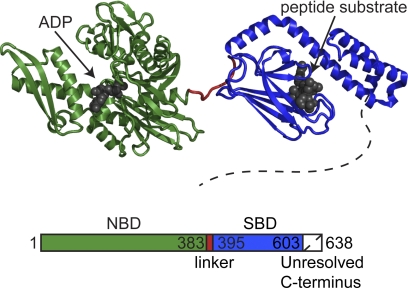

FIGURE 1.

Domains of Hsp70 proteins showing the C-terminal sequence of undefined function. In a substrate-bound conformation of E. coli DnaK (Protein Data Bank code 2KHO) (6, 29, 58), the NBD (green) is joined to the SBD (blue) through a short interdomain linker (red). A peptide substrate is sandwiched between the SBD β-sandwich subdomain and α-helical lid, with 35 crystallographically unresolved residues in the C-terminal tail.

To explore the functional significance of this C-terminal region, we carried out a comparative sequence analysis of Hsp70 family members, and two large and distinct groups emerged based on patterns of C-terminal conservation: those containing the eukaryotic TPR domain interaction motif and those harboring a previously undescribed C-terminal motif shared among diverse bacterial sequences, including Escherichia coli DnaK, and several eukaryotic organellar Hsp70s. Surprisingly, specific conserved sites within the disordered C terminus of DnaK enhance protein refolding activity as well as physiological chaperone function in the cell. These effects occur independently of other defined functions of DnaK and lead us to propose that this region presents a flexibly tethered “universal binding site” capable of keeping substrate proteins at a high local concentration, enabling repeated cycles of binding and release, and thereby facilitating folding. Weak, transient interactions with substrates may also assist in the disruption of misfolded structure. We further suggest that this paradigm of enhancing binding in a reversible and nonspecific manner by flexibly arranged universal weak binding sites may be widespread, but we note that it is difficult to demonstrate this mechanism by traditional methods because it improves performance but is itself nonessential.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sequence Analysis

An Hsp70 multiple sequence alignment (10) was truncated to the C-terminal region corresponding to E. coli DnaK residues 604–638. Pairwise sequence similarity was scored, and the resulting matrix was hierarchically clustered as described previously (11).

Plasmids and Strains

The wild type dnaK gene is carried on vector pMS119 (ptac, pBR322 ori, AmpR) (12). All dnaK mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of pMS119-dnaK by introducing Ala, Lys, Cys, or stop codons. E. coli strains BB1553 (MC4100 Δdnak52::CamR, sidB1) (13) and GP502 (Mph42 ΔsecB, PBAD-dnaKJ, KanR, araC) (14) were used for in vivo assays and DnaK purifications. The E. coli ΔsecB dnaK(1–631) strain was created by λ red-mediated homologous combination of the chromosomal dnaK gene. The bacteriophage genes were expressed from plasmid pSIM9 (15) in E. coli strain MC4100. Cells were then electroporated with a linear DNA recombination substrate composed of a dnaK C-terminal homology arm with the codon at residue 632 mutated to TAA, a Flp recombinase target (FRT) site, a TetR gene taken from plasmid pGPMTet5 (George Munson, University of Miami), a second FRT site, and a dnaK-dnaJ intergenic homology arm. Following recombination, selected clones were used to transfer tetracycline resistance and the linked dnaK truncation to E. coli Keio knock-out strain JW3584-1 (ΔsecB::KanR) (16) by P1 phage transduction. Chromosomal antibiotic resistance genes were removed by expression of Flp recombinase using plasmid pFT-A (17). The plasmid was removed during growth at 37 °C, and the correct losses of antibiotic resistance were verified by plating experiments. The correct chromosomal replacement of the dnaK C terminus and deletion of secB were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Purification of Proteins and Peptides

E. coli DnaK was prepared as previously described (10). E. coli GrpE was purified by utilizing a cleavable His tag (18), which was removed by treatment with His-tagged S219V tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease (19). Concentration was estimated in a Bradford assay using BSA as a standard. E. coli DnaJ was purified using plasmid p29SEN-dnaJ (ptrc, AmpR) (14) following established protocols (20). Concentration was calculated from absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 13,400 m−1 cm−1. The peptide p5 (CLLLSAPRR) was prepared as described previously (10). A purified derivative of p5 (Ala-p5, ALLLSAPRR) N-terminally conjugated with FITC (fp5) was purchased from Genscript. Concentration was determined by absorbance at 494 nm in phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 using an extinction coefficient of 72,000 m−1 cm−1. Staphylococcal nuclease Δ131Δ was prepared as described previously (21).

In Vitro Measurements

All absorbance and luminescence measurements were made using a Biotek Synergy2 microplate reader. Steady-state ATPase activity was measured at 30 °C using an enzyme-coupled system as described previously (10). One μm DnaK was used for all ATPase measurements in the presence or absence of 100 μm p5, 1 μm DnaJ, and 1 μm GrpE dimer, unless otherwise described. The refolding of denatured firefly luciferase (Promega) was measured as described previously (22) using Steady Glo reagent (Promega) as a source of luciferin, 80 nm denatured luciferase, 3.2 μm DnaK, 0.8 μm DnaJ, and 0.4 μm GrpE. All fluorescence measurements were taken on a Photon Technology International fluorometer. DnaK Trp-102 fluorescence emission spectra were measured as described previously (10), in which multiple measurements are averaged resulting in an extra 7% Trp-102 intensity quench due to photobleaching. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements of fp5 incubated with DnaK were made essentially as described previously (12) but in the presence of 1 mm ADP. Kinetic measurements were made using a Bio-Logic stopped-flow device similarly as described previously (23) except that fp5 was used as a substrate with excitation at 494 nm and detection at 517 nm. In control experiments, mixing with buffer instead of ATP showed no increase in fp5 fluorescence over time, and mixing with saturating concentrations of both ATP and p5 gave the same kinetic trace as addition of ATP alone, indicating that release of fp5 was both ATP-dependent and complete. Mutant versions of DnaK with Cys residues introduced by mutagenesis at desired sites were spin-labeled for 24 h in the dark at room temperature with 100-fold excess of S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate (MTSL) in 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm ATP, pH 7.4. Unreacted MTSL was removed by chromatography on a Hi-Prep 26/10 desalting column (Amersham Biosciences). Continuous wave X-band EPR spectra of 100 μm spin-labeled DnaK with or without 1 mm p5 or staphylococcal nuclease Δ131Δ were obtained at 24 °C on a Bruker ELEXSYS E-500 X-Band spectrometer with an ER 4122-SHQE high sensitivity TE102 cylindrical mode single cavity. Reported spectra are the average of 40 scans. Spectral parameters were as follows: 2 milliwatt microwave power; 100 KHz modulation frequency; 1.0 G modulation amplitude; 100 G magnetic field scan; 41.94 s sweep time; and 1.28 ms detector time constant. Line shapes were area-normalized and analyzed using LabView-based software (a generous gift from Wayne Hubell and Christian Altenbach, UCLA). EPR line shapes were simulated using software from Budil et al. (24).

In Vivo Assays

Phage propagation and heat shock assays were performed as described previously using E. coli strain BB1553 transformed with plasmid pMS119-dnaK (13, 25). In the ΔsecB assay with controllable dnaK expression, colonies of E. coli strain GP502 transformed with pMS119-dnaK plasmids were used to inoculate overnight cultures grown at 30 °C in LB media supplemented with 0.5% arabinose, 50 mg/liter ampicillin, and 50 mg/liter kanamycin. Optical density was normalized to 0.4 by dilution with LB medium for each growth. 10 μl of each growth was diluted in 1 ml of water, and 5 μl was used to inoculate 1.5 ml of LB medium supplemented with antibiotics and either 0.5% arabinose, 0.5% glucose, or 0.5% glucose plus 50 μm IPTG. This concentration of IPTG gave maximal growth recovery of strain GP502 transformed with pMS119-dnaK (wild type) in the presence of 0.5% glucose. Growths were carried out at 30 °C in 15-ml falcon tubes secured on their sides in a shaker to ensure efficient aeration. Optical density was measured after 20 h. Samples for Western blots and microscopy were prepared in the same way except that optical density was normalized for Western blot samples. Blots were probed using mouse anti-DnaK and rabbit anti-DnaJ antibodies (Enzo Life Sciences).

RESULTS

Sequence Motif Present in Subset of Hsp70 C Termini Encodes Disordered Tether and Uniquely Conserved Potential Binding Region

An alignment of 730 Hsp70 sequences reveals high conservation in the protein overall (53%) but comparatively low conservation in the C-terminal tail (17% conserved in alignment positions corresponding to E. coli DnaK residues 604–638). In addition, residue variation within C-terminal sequences is not statistically correlated to other positions in the protein, indicating mutational independence of this region from the rest of the Hsp70 structure (10). To investigate sequence features of the C-terminal segment in greater detail, the alignment was truncated to the 604–638 region. A sequence similarity matrix was then calculated and hierarchically clustered (Fig. 2A). Many eukaryotic and bacterial Hsp70 sequences contain large C-terminal deletions. One cluster (151 sequences colored green in Fig. 2A) contains Hsp70 with entire C-terminal deletions, including E. coli HscC and human HspA13. Another cluster (221 sequences colored yellow in Fig. 2A) is composed of Hsp70 with very weakly homologous C termini, such as one subgrouping of sequences with a partial internal deletion culminating in the tripeptide DEL or a similar motif, as exemplified by E. coli HscA. However, two large and distinct sequence clusters with relatively high C-terminal conservation (colored blue and red in the dendrogram in Fig. 2A) emerge from the analysis. As expected, one of the clusters (157 sequences colored blue in Fig. 2A) is composed of strictly eukaryotic Hsp70s that culminate in an EEVD sequence motif for TPR domain interaction, including human paralogs Hsc70 and Hsp70-1.

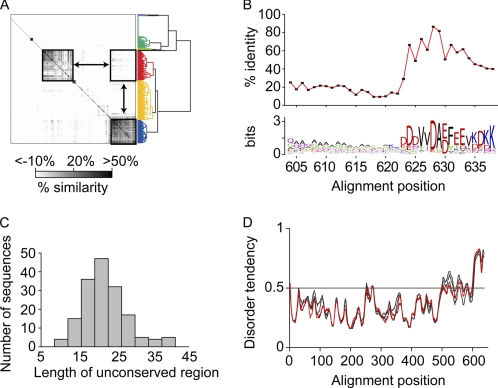

FIGURE 2.

A subset of Hsp70s of bacterial origin share a novel C-terminal sequence motif. A, a sequence similarity matrix shows pairwise conservation between aligned C-terminal Hsp70 sequences. A dendrogram illustrates the organization of patterns within the matrix and is colored according to a hierarchical division where the main clusters are visually apparent. The boxed regions indicate that two internally conserved sequence groups are dissimilar from each other. B, the C-terminal sequence cluster colored red in A is composed of an unconserved region followed by a conserved region. The lower panel shows relative amino acid frequencies for the sequence group (59) and describes a novel motif in the conserved region. C, the unconserved region (corresponding to DnaK residues 604–623) is highly variable in length. D, the amino acid compositions of diverse sequences within the cluster, E. coli DnaK (highlighted in red), B. subtilus DnaK, H. marismortui DnaK, and A. thaliana mtHsc70-1, favor structural disorder following crystallographically resolved structure. Scores >0.5 disorder tendency are significant predictions of disorder using a false positive threshold of 5% (27). In B and D, alignment positions are numbered by E. coli DnaK residue.

Surprisingly, a second, separately conserved cluster (165 sequences colored red in Fig. 2A and listed in a supplemental data set) contains Hsp70 sequences from 148 evolutionarily diverse Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, 12 eukaryotes, of which at least 11 localize to the mitochondria or plastid, and five archaea. This cluster includes E. coli DnaK, the most extensively characterized protein in this group. In addition, the classification of sequences by C-terminal conservation cannot be recreated using full sequence conservation. These data indicate that grouping of sequences based on this C-terminal motif is an evolutionarily widespread phenomenon and is not simply an artifact of phylogenetic subdivision.

The amino acid sequence in the red (bacterial origin) cluster shows a unique sequence motif that is conserved only for alignment positions corresponding to E. coli DnaK residues 624–638 (Fig. 2B). The motif is distinct from that of the previously characterized eukaryotic group, with an EEV tripeptide as the only feature conserved between E. coli DnaK and human Hsc70. This tripeptide sequence occurs as part of the conserved TPR-binding EEVD motif at the extreme C terminus in eukaryotes and is five residues from the C terminus in the bacterial cluster. N-terminal to the conserved C-terminal 15 residues is a region of low sequence complexity with a broad length distribution ranging from ∼10 to 40 amino acids (Fig. 2C). The low sequence complexity and variable length of this region suggest that it may act as flexible tether between the structured SBD lid and the more conserved region of the C-terminal tail. The length of this variable region in E. coli DnaK, 604–623, is representative of the distribution mean (20 residues).

The amino acid content of the flexible tether (enriched in Ala, Gly, and Gln) and the more conserved C-terminal region suggest sequence selection for intrinsic disorder (26). This expectation was tested by subjecting representative sequences from the bacterial group to disorder prediction methods based on amino acid composition. Similar results were obtained using both metaPrDOS (27) and PONDR (28) prediction algorithms. The sequences of E. coli DnaK (Gram-negative), Bacillus subtilis DnaK (Gram-positive), Haloarcula marismortui DnaK (archaeal), and Arabidopsis thaliana mtHsc70-1 (mitochondrial) are all highly predictive of structural disorder following residue 603 (Fig. 2D). Direct support for these predictions is provided by the finding that in solution the portion of E. coli DnaK following residue 603 has been found to lack stable structure (6), is susceptible to proteolysis, and its removal facilitates crystallization of the SBD (29).

Intriguingly, residues 624–633 are predicted to be a protein-binding region, based on their potential to gain energetically stabilizing interactions, using the program ANCHOR (30). This region has the highest conservation of the entire sequence motif. Although the C terminus is not predicted to have a unique structure, its sequence specificity raises the possibility that it assumes a structure upon interaction with partners. Also, the eukaryotic TPR domain-binding role of the analogous region suggests that there may be an as yet undefined partner that interacts with this region in the bacterial and organellar Hsp70s. However, we made a construct of glutathione S-transferase fused to the DnaK C-terminal peptide 619–638 and looked for interaction partners in cell lysates from several E. coli strains prepared under normal or stress conditions by pull down using glutathione affinity resin (supplemental data). No partners were found. This result may be because there is not a specific binding partner, or because the binding mediated by the C-terminal region is weak and transient, or because cellular partners are present in low abundance.

DnaK C-terminal Truncation Results in Cellular Defects upon Heat Shock or Chaperone Depletion

Two commonly used cellular assays for chaperone function of E. coli DnaK are bacteriophage λ propagation, which requires host Hsp70 to disassemble a phage protein complex in order to initiate phage DNA replication, and growth following protein misfolding and aggregation induced by heat shock (13, 31, 32). Previous studies report no defect in phage propagation upon truncation of the E. coli DnaK C terminus (33–35), and in agreement with these studies, we confirm that a plasmid expressing DnaK with the entire disordered C terminus removed (1–603) is fully capable of propagating λ in an E. coli dnaK-knock-out strain at 30 °C (Fig. 3A). However, we observe significant growth defects after heat shock at 43 °C in E. coli expressing DnaK with just a seven-residue truncation (1–631) (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, cells expressing DnaK extended with a C-terminal His6 tag also show growth defects after heat shock (supplemental Fig. S1).

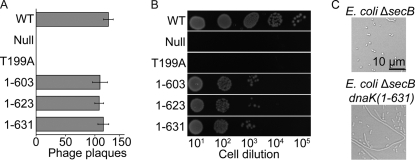

FIGURE 3.

DnaK C-terminal truncation results in cellular defects upon heat shock or chaperone depletion. A, in a DnaK-dependent process, an E. coli ΔdnaK strain (BB1553) is fully capable of propagating phage λ at 30 °C when expressing plasmid-encoded C-terminal truncations of DnaK. B, the same strain shows impaired growth upon 43 °C heat shock when expressing C-terminal truncations of DnaK. DnaK T199A cannot hydrolyze ATP effectively (40) and is a negative control. C, at 30 °C, E. coli ΔsecB cells have a normal rod-shaped morphology, whereas E. coli ΔsecB dnaK(1–631) cells are prone to filamentation.

Results of in vivo assays are sensitive to the genetic background of the E. coli cells used as well as to complications that arise from truncations that extend into the structured SBD lid. For example, it was reported previously that DnaK truncated at residue 628 or 538 supported growth at heat shock temperature in the E. coli dnaK756 strain (34), whereas others have reported growth defects upon heat shock for DnaK(1–538) (33). In the dnaK756 strain, the chromosomal copy of DnaK harbors three point mutations and the σ32 heat shock transcription factor is wild type. Perturbation of DnaK likely leads to the increased expression of other heat shock proteins in a wild type σ32 background (36), which may partially compensate for a DnaK defect. In addition to dnaK deletion, the strain used here (BB1553) has reduced levels of co-operonic dnaJ expression and harbors a secondary σ32 mutation that suppresses high level expression of genes under control of the heat shock promoter (13). We also note that the effects of C-terminal truncations within the SBD lid (prior to residue 603) are difficult to interpret physiologically because of the now well established tendency for the truncated α-helical subdomain to unwind and bind to the substrate-binding cleft in the SBD (35, 37).

Defects in DnaK activity can be obscured by the partially overlapping functions among different chaperones. To gain greater insight into the functions of the DnaK C terminus, we took advantage of the synthetic lethality recently reported for E. coli ΔsecB ΔdnaK (14). Starting with E. coli ΔsecB, we introduced a truncation into the chromosomal dnaK gene after residue 631 by homologous recombination. At 30 °C, the resulting strain shows a slightly reduced growth rate (supplemental Fig. S2A) and a highly filamentous morphology (Fig. 3C), revealing a requirement for the intact DnaK C terminus at unstressed temperature in the absence of the chaperone SecB.

Ullers and colleagues previously developed E. coli strain GP502, with a secB knock-out and the co-operonic dnaK and dnaJ genes placed under control of the PBAD promoter. When grown in medium supplemented with 0.5% arabinose, these cells have normal (not stress-induced) levels of DnaK and DnaJ. Furthermore, growth in medium supplemented with glucose to inhibit PBAD expression results in significant protein aggregation (14). Given the observed influence of the DnaK C terminus on cellular health in the absence of SecB, and the partially overlapping capabilities of SecB and DnaJ to bind misfolded proteins and maintain their solubility (38, 39), we hypothesized that cells depleted of both SecB and DnaJ would be even more sensitive to the influence of the DnaK C terminus. This strain was transformed with a plasmid that encodes a dnaK gene with an IPTG-inducible promoter, allowing controlled expression of chromosomal wild type dnaK and dnaJ genes and plasmid-encoded dnaK variants (Fig. 4A). Three growth conditions provide an internal positive control (grown with arabinose; chromosomal wild type dnaK and dnaJ expression), internal negative control (grown with glucose; repression of all dnaK and dnaJ expression), and test condition (grown with glucose plus IPTG; plasmid-encoded dnaK expression in the absence of dnaJ expression) (Fig. 4B). All of these conditions are in the absence of SecB.

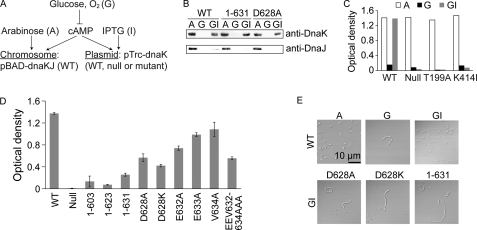

FIGURE 4.

A stringent assay for DnaK C-terminal function reveals the site-specific contributions of conserved residues. A, E. coli strain GP502 (ΔsecB, PBAD-dnaKdnaJ) (14) transformed with a plasmid carrying an IPTG-inducible dnaK gene allows for the controlled expression of wild type dnaK and dnaJ, and separately, a dnaK variant. B, Western blots of E. coli GP502 transformed with different dnaK variants show the expected expression profiles when grown in the presence of different metabolites (as depicted in A). C, control experiments demonstrate that all transformants grown at 30 °C show high and low levels of growth in medium supplemented with arabinose (A) and glucose (G), respectively, but growth rescue in media supplemented with glucose plus IPTG (GI) is dependent on plasmid-encoded DnaK function. DnaK T199A (40) and DnaK K414I (12) are non-functional DnaK constructs and act as negative controls. D, in the same assay, C-terminal mutants of DnaK are unable to support normal growth when wild type DnaK and DnaJ are depleted in the glucose plus IPTG condition. All transformants behave normally in control conditions (supplemental Fig. S3). Importantly, site-specific mutations result in growth defect severity following the observed conservational pattern (Fig. 2B). E, defects in growth rate coincide with cellular filamentation.

Accordingly, we find that strain GP502 transformed with plasmid-encoded wild type dnaK shows a high growth rate in medium supplemented with arabinose, a very low growth rate in medium supplemented with glucose, and rescued growth in medium supplemented with glucose plus IPTG (Fig. 4C). The trends in growth rate are mirrored by features of cell morphology, with a filamentous phenotype observed only in the presence of glucose (Fig. 4E). In contrast, growth is not rescued by IPTG in cells carrying an empty vector or carrying a vector that expresses non-functional DnaK with mutation at T199A or K414I (12, 40). C-terminal truncation constructs 1–603, 1–623, and 1–631 behave normally in control conditions (supplemental Fig. S3), but when grown in the IPTG rescue condition, all show severe defects with little or no growth benefit relative to the empty vector (Fig. 4D) and have a filamentous morphology (Fig. 4E). Therefore, depleting DnaJ exacerbates the C-terminal truncation phenotype observed in the absence of SecB alone (supplemental Fig. S2), providing a stringent assay for DnaK C-terminal function.

Site-specific Contributions of C-terminal Tail to Cellular Function

Cells depleted of SecB and DnaJ reveal a severe phenotype upon DnaK C-terminal truncation and allow us to explore specific sequence requirements within the conserved C-terminal tail in greater detail. Alanine substitutions were made in DnaK at the most highly conserved position in the bacterial C-terminal sequence cluster, Asp-628, and within the 632EEV634 motif shared with eukaryotic Hsp70s. Cells expressing plasmid-encoded C-terminal mutation constructs show a high rate of growth in the presence of arabinose (positive control) and a low rate of growth in the presence of glucose (negative control), as expected (supplemental Fig. S3). All of these site-specific mutations result in significant growth defects in the test condition (Fig. 4, D and E), as would be anticipated if the pattern of conservation arose from specific residue roles (Fig. 2B), with mutation at Asp-628 having the greatest effect. Charge reversal (D628K) is more deleterious than removal of charge (D628A). The triple Ala mutation at the less conserved 632EEV634 tripeptide is defective to a similar extent as the single Asp-628 mutations, but none of these changes cause as significant a defect as the truncation of seven residues in DnaK(1–631), indicating that there are multiple determinants for function dispersed throughout the conserved region.

DnaK C-terminal Region Is Not Required for Binding of a Peptide Substrate, Interdomain Allostery, or Co-chaperone Interaction

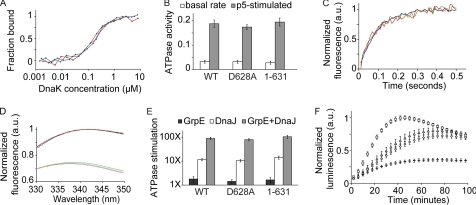

To explore the role of the conserved C terminus in E. coli DnaK, we constructed and purified DnaK with this region truncated (DnaK(1–631)), as well as a point mutant, D628A, that caused a significant in vivo defect, and compared their performances using an array of well-established Hsp70 in vitro functional assays. In the ADP-bound state, Hsp70s bind tightly to their substrates. This binding has been characterized through the use of oligopeptides, such as the nine-residue substrate CLLLSAPRR (p5). As measured by fluorescence anisotropy using a FITC-conjugated derivative of p5 (fp5), wild type DnaK D628A and DnaK(1–631) all show normal binding ability (Kd values of ∼150 nm with overlapping confidence intervals) (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Disruption of the C-terminal motif in E. coli DnaK impairs protein refolding activity independently of known mechanisms for chaperone function. A, in an ADP-bound, high substrate affinity state, DnaK(1–631) (red) and D628A (green) bind to fp5, a substrate peptide containing a linked fluorescein group, with the same affinity as wild type DnaK (blue). B, the basal ATPase activity of DnaK and its allosteric stimulation by the substrate peptide p5 are normal in C-terminal mutants. ATPase activity is expressed in units of moles ATP consumed per mol DnaK per minute. C, upon rapid mixing with ATP, fp5 release follows the same kinetic profile in DnaK(1–631) (red), D628A (green), and wild type DnaK (blue). D, DnaK(1–631) (red), D628A (green), and wild type (blue) display the same characteristic blue shift and intensity quench of Trp fluorescence upon ATP binding, indicating that they undergo productive interdomain docking (7, 41). The lower and more lightly shaded traces are from measurements after ATP addition. E, the stimulation of DnaK ATPase activity by co-chaperones GrpE and DnaJ are indistiguishable among the three constructs. F, after diluting chemically denatured luciferase into aqueous buffer, wild type DnaK (squares) promotes faster formation and higher yield of native luciferase than DnaK(1–631) (diamonds), D628A (triangles), or samples omitting DnaK (dashes).

Interdomain allostery in Hsp70s is revealed by the activation of their basal ATPase activity upon substrate binding and reciprocally by a reduction in substrate affinity (enhanced release kinetics) upon ATP binding. Wild type DnaK D628A and DnaK(1–631) all show basal and p5-stimulated ATPase rates within experimental error of one another and show approximately a 6-fold stimulation by p5 (Fig. 5B), as expected (10). The substrate fp5 is a suitable probe for measuring ATP stimulation of peptide release, as its fluorescence intensity is quenched upon binding by DnaK (supplemental Fig. S4). Here again, data obtained by stopped-flow measurements of peptide release upon ATP binding showed kinetics in the range of 11.0 ± 0.3 s−1 for the mutated C-terminal constructs, indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 5C) and consistent with previously reported values (23).

In addition to the functional measurement of interdomain allostery by ATPase activity, a structural basis of allostery can be assessed using the sole intrinsic tryptophan of DnaK. Nucleotide-binding domain residue Trp-102 undergoes fluorescence emission changes upon binding of ATP and in the presence of the SBD lid and is therefore a probe for functional ATP-induced interdomain docking (41). The physical proximity of the disordered C-terminal tail to the structured SBD lid suggests that C-terminal mutation might alter lid interaction with the nucleotide-binding domain. However, in wild type DnaK D628A and DnaK(1–631), the Trp-102 fluorescence emission maximum shifts to the same extent, viz. from 342 to 338 nm, in the presence of ATP (Fig. 5D and supplemental Fig. S5). The quenching of Trp-102 fluorescence intensity upon ATP binding was also identical to that of wild type protein for each of these constructs (26 ± 1%), providing additional support for normal interdomain packing.

By analogy with the role of the eukaryotic C terminus in co-chaperone binding, the C-terminal region of DnaK could be involved in interaction with partner co-chaperones, DnaJ and GrpE. These co-chaperones affect DnaK function in part by increasing the steady-state ATPase activity of DnaK, and in turn, the rate of DnaK conformational cycling between high and low affinity substrate-binding states. GrpE catalyzes nucleotide exchange, and DnaJ stimulates ATP hydrolysis. The rate-limiting step of DnaK basal ATPase activity is ATP hydrolysis; therefore, DnaJ alone causes a much larger increase in DnaK ATPase activity than GrpE alone, whereas the combination is synergistic (42). The ATPase activity of wild type DnaK was stimulated 1.6-fold by GrpE, 12-fold by DnaJ, and 90-fold by both co-chaperones together. Importantly, no difference was observed for the C-terminally mutated DnaK D628A or DnaK(1–631) (Fig. 5E). These data are consistent with previous reports that DnaK constructs with truncations exceeding the conserved region reported here have little to no effect on DnaJ binding (33, 34). In addition to its direct association with DnaK, DnaJ can also bind misfolded substrates and deliver them to DnaK, coupling the presentation of misfolded substrates to DnaK with the conversion of DnaK to an ADP-bound, high substrate affinity state (3). We found that the cooperative stimulation of DnaK ATPase activity by DnaJ and substrates could only be detected in a narrow range of molar ratios, but that even in these circumstances, there was no detectable difference between wild type DnaK and C-terminal mutants in their mutual stimulation by DnaJ and the oligopeptide substrate p5 or an unfolded protein substrate (reduced carboxymethylated α-lactalbumin) (supplemental Fig. S6).

DnaK C-terminal Region Enhances Its Protein Refolding Efficiency

Although many of the biochemical assays of DnaK function show no measurable difference among C-terminal constructs, none explores its ability to impact the folding of a substrate. Thus, we tested chaperone function more directly by measuring an ability to protect a refolding protein from aggregation and assist its folding to the native state. Purified DnaK variants together with co-chaperones DnaJ and GrpE were used in a reconstituted refolding assay of denatured firefly luciferase. Successful refolding of luciferase to its native state is measured by its ability to oxidize the small molecule luciferin, which leads to emission of light (43). Strikingly, we find that both DnaK(1–631) and D628A show markedly reduced ability to assist refolding of denatured luciferase (Fig. 5F). Both the initial rate of appearance of enzymatically active folded luciferase (monitored by photon count) and the total amount of native luciferase (monitored by maximal luminescence) are reduced when the C-terminal region of DnaK is truncated or mutated. After subtracting a DnaK− sample, mutations in the conserved DnaK C-terminal region result in an initial rate of just 25–35% of that observed with wild type DnaK rate and maximal luminescence that is 50–60% of the wild type level. Note that the reduction in light emission at later time points for all samples is due to the accumulation of an inhibitory by-product of the luciferase enzymatic reaction and thus correlations to refolding activity of DnaK are based solely on initial rate and maximal activity (22, 44).

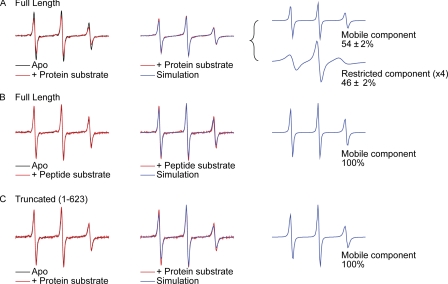

Direct Interaction of DnaK C Terminus with Misfolded Protein Substrate

Given that a refolding defect is observed for C-terminally mutated DnaK in the presence of only denatured substrate, DnaJ and GrpE, whereas intramolecular and DnaJ/GrpE-assisted functions are unaffected (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S6), we hypothesized that the C terminus may act by direct interaction with misfolded protein substrates. To test this idea, we designed an experiment to test whether binding of an unfolded protein substrate to DnaK reduced the mobility of the C-terminal region. Staphylococcal nuclease fragment Δ131Δ has been shown to be monomeric under the conditions of our experiments, to lack the ability to fold into native protein, and to bind DnaK (21, 45), and thus, we selected it as model protein substrate. Full-length DnaK was spin-labeled at residue 622, just prior to the conserved 624–638 region, through introduction of a Cys residue and attachment of the nitroxide derivate MTSL. EPR spectra for the spin label at 622 are significantly broadened and concomitantly reduced in intensity upon binding to Δ131Δ, indicating C-terminal immobilization upon binding to a misfolded substrate (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S7A). Experimental data for the apo state (DnaK without substrate) are fit well with a single mobile component, whereas a second, restricted component of C-terminal motion must be introduced to fit the spectrum of the Δ131Δ-bound state. In contrast, binding to the oligopeptide substrate p5, which does not extend beyond the canonical β-sandwich binding pocket and is therefore not expected to present sequence accessible to C-terminal interaction, produces a line shape for the C-terminal spin label that is superimposable with that of the apo state (Fig. 6B and supplemental Fig. S7B). We examined binding of Δ131Δ to a truncated DnaK construct (1–623), which lacks the C-terminally conserved region and is neither competent for enhanced refolding activity in vitro (Fig. 5) nor capable of protection from stress under stringent conditions (Figs. 3 and 4). There is no indication of immobilization of the spin label (on Cys at position 623) in this construct (Fig. 6C and supplemental Fig. S7C). These data strongly support a direct interaction of the conserved region of the C terminus with unfolded protein substrates and suggest a mode of chaperone action that has not been suitably addressed by prior mechanistic models for Hsp70 function.

FIGURE 6.

The DnaK C terminus interacts with a misfolded protein substrate. A, the EPR line shape of DnaK K662C-MTSL (black, left panel) is broadened in the presence of staphylococcal nuclease Δ131Δ (red), demonstrating C-terminal immobilization upon binding to a misfolded protein substrate. The simulated line shape for Δ131Δ-bound DnaK is shown in blue and overlaid on the experimental line shape (center panel). The component spectra are shown on the right panel with their relative percentages labeled. B, the line shape of DnaK K662C-MTSL (black, left panel) is unaffected by binding to the peptide substrate p5 (red) with the simulated line shape (blue) and its single mobile component shown on the right panel (blue). C, EPR line shapes of truncated DnaK 1–623C-MTSL in the presence (red, left panel) and absence (black) of Δ131Δ with the simulated line shape (blue) and its single mobile component shown on the right panel (blue). Also see supplemental Fig. S7.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a novel C-terminal conservation pattern in a large and diverse subset of Hsp70 isoforms of bacterial origin and validated its natural function in cellular systems under varying degrees of stress using the E. coli Hsp70, DnaK. The conserved sequence character of the entire C-terminal region predicts that it is disordered, which raises interesting questions regarding its function, given the roles of structural disorder in other proteins and chaperone systems (46). Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) can act as scaffolds for larger molecular assemblies. Interestingly, E. coli YbbN has been identified as a DnaK-interacting chaperone with an atypical TPR domain (47, 48), and DnaK cooperates with the E. coli Hsp90, ans HtpG (49), in possible analogy to assemblies with eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s. Nonetheless, a C-terminal defect is manifested in a simple reconstituted refolding assay with only DnaJ and GrpE present, and we observe no deficiency in assays that probe functional interactions between DnaK and these co-chaperones upon C-terminal mutation. Thus, a scaffolding role for the C terminus is not directly supported by the current data.

Another possibility is that the C-terminal tail shields misfolded regions of bound substrate and blocks aggregation, by analogy to small heat shock proteins (50). However, the conservation of specific residues in the C terminus and functional defect upon charge reversal at a single site in DnaK D628K demonstrate that that the C-terminal tail's function cannot be ascribed to occlusion based on chain length and disorder alone.

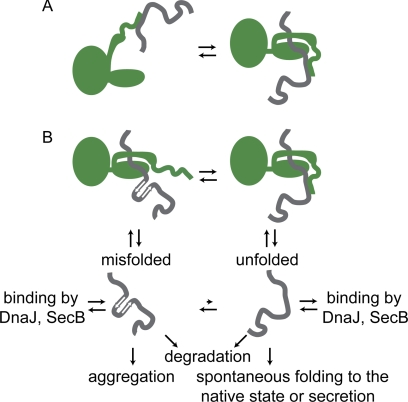

Given the sequence properties of the C-terminal region for a multitude of Hsp70s and our direct in vitro evidence for binding of this region to a misfolded substrate, we propose that the more highly conserved extreme C-terminal sequence (residues 624 to 638 of DnaK) region presents a weak, auxiliary binding site for denatured substrate proteins. Upon ATP-induced release from the canonical substrate-binding site, weak association with the C-terminal IDR would retain the substrate in the vicinity of the chaperone and thus promote subsequent cycles of binding and release (Fig. 7A). This model is consistent with the finding that IDRs frequently act as flexible tethers and present molecular recognition features; the resulting flexibility enables the same regions to engage in multiple modes of binding (51), as suggested here. For example, the N-terminal disordered region of the small heat shock protein PsHsp18.1 allows the molecule to recognize a variety of misfolded substrates (52), as do the N- and C-terminal disordered regions of the ubiquitin ligase San1 (53).

FIGURE 7.

A model for Hsp70 C-terminal function. The disordered C-terminal region of Hsp70 (green) acts as a flexible, multivalent binding site for direct interaction with substrate proteins (gray), which may contribute to the chaperone mechanism in different ways. A, enhanced kinetic partitioning. After ATP-induced lid opening and release of the substrate to solvent, the substrate may fold to the native state or repeatedly rebind the chaperone. The C-terminal tail weakly interacts with substrates even after release, increasing the probability of reforming a stable substrate-chaperone complex. B, local unfolding. Unfolded proteins may spontaneously fold to the native state or become kinetically trapped in a misfolded state, leading to possible aggregation. Upon binding to Hsp70, the C-terminal tail disrupts locally misfolded structure through transient multivalent binding, thereby relieving the kinetic trap and allowing the release of unfolded substrate. ATP-mediated substrate release in DnaK as well as DnaJ-mediated delivery of substrates to DnaK are not shown for simplicity.

An additional outcome of substrate binding to the disordered C-terminal tail can be envisioned: the binding itself can transiently disrupt non-native local structure of misfolded substrates, whereas the substrate is bound to the higher affinity site in the β-sandwich binding pocket. Local unfolding would facilitate conformational search of the substrate chain, which may fold spontaneously upon release or be subjected to ongoing cycles of interaction (Fig. 7B). This idea is similar to an iterative annealing model for GroEL function (54). The general idea that chaperones may exploit weak multivalent binding events offered by an IDR at a secondary proximal site was suggested by Tompa and Csermely (50), who termed it entropy transfer. In the cell, multivalent molecular recognition by the DnaK C terminus may accommodate the chaperoning of diverse cellular substrates, as opposed to other E. coli Hsp70s lacking the C-terminal motif that have specialized functional roles. For example, E. coli HscA specifically assists in the maturation of iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein IscA (55) and has a natural C-terminal deletion. The chaperones SecB and DnaJ, which are functionally linked to the C-terminal role of DnaK, play related roles in the protection of misfolded states from aggregation and degradation as well in the maintenance of the unfolded state for delivery to the secretory pathway (38, 39, 56, 57).

A weak, multivalent binding of the C-terminal IDR and the heterogeneity of target substrates suggest that other sequence variations might functionally substitute in some cases. Indeed, complete truncation of the DnaK C-terminal region after the structured SBD lid and its replacement with a His tag actually enhances the refolding of exogenous firefly luciferase substrate (22). Given the evolutionary selection of the C-terminal motif (Fig. 2), one might suspect that it is optimized for substrates of bacterial origin.

We note that the mechanism we propose might also be utilized by eukaryotic cytoplasmic Hsp70s (8, 9). If so, evolution has overlaid more specialized functionality on the basic function by selecting C-terminal motifs that also promote assembly with other chaperone and degradation machinery. Thus, their C-terminal regions may play multiple roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre Génévaux (Université Paul-Sabatier), Lyra Chang, and Jason Gestwicki (University of Michigan); Carol Gross (University of California, San Francisco); David Shortle (Johns Hopkins University); and Karsten Theis and Peter Chien (University of Massachusetts, Amherst) for sharing plasmids and strains.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM027616.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Figs. S1–S6, data, and additional references.

- NBD

- nucleotide-binding domain

- SBD

- substrate-binding domain

- fp5

- p5 conjugated with FITC

- IDR

- intrinsically disordered region

- MTSL

- S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate

- TPR

- tetratricopeptide repeat

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- FRT

- Flp recombinase target

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- a.u.

- arbitrary units.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2002) Science 295, 1852–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bukau B., Deuerling E., Pfund C., Craig E. A. (2000) Cell 101, 119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayer M. P., Bukau B. (2005) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 670–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rist W., Graf C., Bukau B., Mayer M. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16493–16501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Swain J. F., Dinler G., Sivendran R., Montgomery D. L., Stotz M., Gierasch L. M. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 27–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bertelsen E. B., Chang L., Gestwicki J. E., Zuiderweg E. R. P. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8471–8476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu Q., Hendrickson W. A. (2007) Cell 131, 106–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tsai M. Y., Wang C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5958–5962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu S. M., Wang C. (1996) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 332, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smock R. G., Rivoire O., Russ W. P., Swain J. F., Leibler S., Ranganathan R., Gierasch L. M. (2010) Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marcelino A. M., Smock R. G., Gierasch L. M. (2006) Proteins 63, 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montgomery D. L., Morimoto R. I., Gierasch L. M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 286, 915–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bukau B., Walker G. C. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 4027–4036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ullers R. S., Ang D., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3101–3106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharan S. K., Thomason L. C., Kuznetsov S. G., Court D. L. (2009) Nat. Protoc. 4, 206–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K. A., Tomita M., Wanner B. L., Mori H. (2006) Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006 0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pósfai G., Koob M. D., Kirkpatrick H. A., Blattner F. R. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 4426–4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang L., Thompson A. D., Ung P., Carlson H. A., Gestwicki J. E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21282–21291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kapust R. B., Tözsér J., Fox J. D., Anderson D. E., Cherry S., Copeland T. D., Waugh D. S. (2001) Protein Eng. 14, 993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang L., Bertelsen E. B., Wisén S., Larsen E. M., Zuiderweg E. R., Gestwicki J. E. (2008) Anal. Biochem. 372, 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alexandrescu A. T., Abeygunawardana C., Shortle D. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 1063–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aponte R. A., Zimmermann S., Reinstein J. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 399, 154–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Theyssen H., Schuster H. P., Packschies L., Bukau B., Reinstein J. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 263, 657–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Budil D. E., Lee S., Saxena S., Freed J. H. (1996) J. Magn. Reson. 120, 155–189 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clerico E. M., Zhuravleva A., Smock R. G., Gierasch L. M. (2010) Biopolymers 94, 742–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dunker A. K., Brown C. J., Obradovic Z. (2002) Adv. Protein Chem. 62, 25–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishida T., Kinoshita K. (2008) Bioinformatics 24, 1344–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dunker A. K., Uversky V. N. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 229–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu X., Zhao X., Burkholder W. F., Gragerov A., Ogata C. M., Gottesman M. E., Hendrickson W. A. (1996) Science 272, 1606–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dosztányi Z., Mészáros B., Simon I. (2009) Bioinformatics 25, 2745–2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yochem J., Uchida H., Sunshine M., Saito H., Georgopoulos C. P., Feiss M. (1978) Mol. Gen. Genet. 164, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osipiuk J., Georgopoulos C., Zylicz M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4821–4827 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gässler C. S., Buchberger A., Laufen T., Mayer M. P., Schröder H., Valencia A., Bukau B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15229–15234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suh W. C., Lu C. Z., Gross C. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30534–30539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swain J. F., Schulz E. G., Gierasch L. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1605–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paek K. H., Walker G. C. (1987) J. Bacteriol. 169, 283–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pellecchia M., Montgomery D., Stevens D., Vander Kooi C., Feng H., Gierasch L. Z., E RP. (2000) Nat. Struct. Mol. Bio. 7, 298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langer T., Lu C., Echols H., Flanagan J., Hayer M. K., Hartl F. U. (1992) Nature 356, 683–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ullers R. S., Luirink J., Harms N., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7583–7588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Buchberger A., Theyssen H., Schröder H., McCarty J. S., Virgallita G., Milkereit P., Reinstein J., Bukau B. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16903–16910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moro F., Fernández V., Muga A. (2003) FEBS Lett. 533, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCarty J. S., Buchberger A., Reinstein J., Bukau B. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 249, 126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schröder H., Langer T., Hartl F. U., Bukau B. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4137–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fraga H., Fernandes D., Fontes R., Esteves da Silva J. C. G. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 5206–5216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Palleros D. R., Shi L., Reid K. L., Fink A. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13107–13114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kthiri F., Le H. T., Tagourti J., Kern R., Malki A., Caldas T., Abdallah J., Landoulsi A., Richarme G. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374, 668–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin J., Wilson M. A. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19459–19469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Genest O., Hoskins J. R., Camberg J. L., Doyle S. M., Wickner S. (2011) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8206–8211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tompa P., Csermely P. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 1169–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smock R. G., Gierasch L. M. (2009) Science 324, 198–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jaya N., Garcia V., Vierling E. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15604–15609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rosenbaum J. C., Fredrickson E. K., Oeser M. L., Garrett-Engele C. M., Locke M. N., Richardson L. A., Nelson Z. W., Hetrick E. D., Milac T. I., Gottschling D. E., Gardner R. G. (2011) Mol. Cell 41, 93–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Todd M. J., Lorimer G. H., Thirumalai D. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4030–4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vickery L. E., Cupp-Vickery J. R. (2007) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 95–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Randall L. L., Hardy S. J. (2002) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1617–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sakr S., Cirinesi A. M., Ullers R. S., Schwager F., Georgopoulos C., Genevaux P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23506–23514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harrison C. J., Hayer-Hartl M., Di Liberto M., Hartl F., Kuriyan J. (1997) Science 276, 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.