Abstract

Ehrlich's pioneering chemotherapeutic experiments published in 1904 (Ehrlich, P., and Shiga, K. (1904) Berlin Klin. Wochenschrift 20, 329–362) described the efficacy of a series of dye molecules including trypan blue and trypan red to eliminate trypanosome infections in mice. The molecular structures of the dyes provided a starting point for the synthesis of suramin, which was developed and used as a trypanocidal drug in 1916 and is still in clinical use. Despite the biological importance of these dye-like molecules, the mode of action on trypanosomes has remained elusive. Here we present crystal structures of suramin and three related dyes in complex with pyruvate kinases from Leishmania mexicana or from Trypanosoma cruzi. The phenyl sulfonate groups of all four molecules (suramin, Ponceau S, acid blue 80, and benzothiazole-2,5-disulfonic acid) bind in the position of ADP/ATP at the active sites of the pyruvate kinases (PYKs). The binding positions in the two different trypanosomatid PYKs are nearly identical. We show that suramin competitively inhibits PYKs from humans (muscle, tumor, and liver isoenzymes, Ki = 1.1–17 μm), T. cruzi (Ki = 108 μm), and L. mexicana (Ki = 116 μm), all of which have similar active sites. Synergistic effects were observed when examining suramin inhibition in the presence of an allosteric effector molecule, whereby IC50 values decreased up to 2-fold for both trypanosomatid and human PYKs. These kinetic and structural analyses provide insight into the promiscuous inhibition observed for suramin and into the mode of action of the dye-like molecules used in Ehrlich's original experiments.

Keywords: ATP, Cancer Therapy, Crystallography, Drug Action, Enzyme Inhibitors, Glycolysis, Parasite Metabolism, Pyruvate Kinase, X-ray Crystallography

Introduction

Therapies against trypanosomatid-borne diseases have evolved from the historic work of Paul Ehrlich (1), who was the first to provide a rationale for a chemotherapeutic approach in the treatment of infectious diseases. He used a series of naphthalene dyes related to trypan red and trypan blue (see Fig. 1a) and demonstrated that they had trypanocidal activity. Trypan blue successfully cleared trypanosomatid infections in mouse models but were not successful in other mammals. Ehrlich noted in his mouse trials where he tested over 50 related diazo dyes that mice treated with trypan red retained a red color for weeks and even months. This side effect was a significant drawback to its use in human therapy, and the search for a colorless analog was pursued by chemists at Bayer, who synthesized Bayer 205, now known as suramin (see Fig. 1c), which is still used in the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) caused by the parasitic protist Trypanosoma brucei (2). Additional uses for suramin have been explored in the treatment of human cancers (3) and HIV infection (4), where it was the first drug to show antiviral activity (5). It is evident from the mass of literature that suramin is a promiscuous inhibitor of many enzymes and receptors and shows a range of interesting clinically relevant effects (6, 7). Despite following none of the currently accepted criteria for drug-likeness (8), suramin and a number of diverse analogues (9, 10) are still of clinical interest in an ever growing repertoire of diseases (11–13).

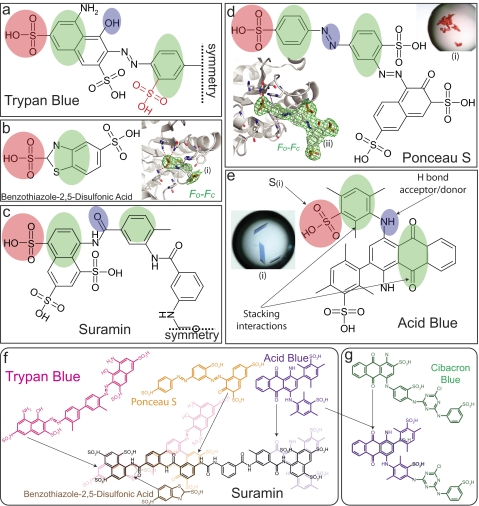

FIGURE 1.

Trypan dyes and other sulfonic acid compounds have similar structural features. a, two-dimensional representation of one symmetrical half (as indicated by the dashed symmetry line) of trypan blue and trypan red (trypan red contains one additional sulfono group, indicated by red lettering). b, BDS bound in the active site of LmPYK (i). The BDS molecule is shown with an unbiased Fo − Fc electron density map contoured at 3 σ (green). Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed red lines, and stacking interactions are shown as dashed purple lines. c, one symmetrical half of the colorless trypan analog, suramin. d, co-crystal (i) of Ponceau S bound in the active site of TcPYK (ii). e, co-crystal (i) of LmPYK and the AB80 molecule. f, a superimposition between dye-like molecules and suramin. Common groups superimpose onto the structure of suramin, highlighting the chemical relationships within the series of molecules. This figure highlights two-dimensional chemical similarities and not necessarily three-dimensional binding similarities (as illustrated by the shaded ellipses in panels a–e). g, a superimposition between Cibacron blue (a molecule commonly used for affinity purification of PYK) and AB80. Shaded ellipses in panels a–e highlight key binding characteristics observed in the LmPYK-sulfonic acid structures obtained: site S1, pink ellipse, a sulfono group (S(i)) is observed bound in a near identical position in all complexes; site S2, green ellipse, a stacking interaction with His-54 is conserved in all structures; site S3, green ellipse, a second stacking interaction with Tyr-59 and Pro-29 is observed for suramin, Ponceau S, and AB80; site S4, blue ellipse, a hydrogen bound acceptor/donor is also commonly observed. In the LmPYK-Ponceau S, the azo group forms a hydrogen bond via the hydroxyl group of Tyr-59. Only microcrystals were obtained with trypan blue, but the common PYK binding characteristics are also observed. Suramin and trypan blue are symmetrical molecules, and only half the molecule is shown (as indicated by the dashed symmetry lines).

Suramin has been characterized as an inhibitor of T. brucei and mammalian glycolytic enzymes (14–16) and has been shown to inhibit all seven of the T. brucei glycolytic enzymes isolated from glycosomes (peroxisome-like organelles specific for kinetoplastid protists that harbor the first seven glycolytic enzymes converting glucose into 3-phosphoglycerate) with IC50 values between 3 and 100 μm (15). The three glycolytic enzymes found in the cytosol (phosphoglycerate mutase, enolase, and pyruvate kinase (PYK)2 (17)) were not examined in these experiments. The importance of glycolytic enzymes for the viability of T. brucei has been confirmed by RNAi knockdown of glycosomal and cytosolic enzymes (including PYK) with consequent death of the parasite (18, 19).

PYK catalyzes the final reaction of glycolysis in which P-enolpyruvate and ADP are converted into pyruvate and ATP. All trypanosomatid PYKs share a high degree of sequence identity (73–80%), with highly conserved active and allosteric effector binding sites (supplemental Fig. S1). We have previously characterized the structure of PYK from the trypanosomatid parasite, Leishmania mexicana (LmPYK), a homotetrameric enzyme (20) in which each monomer of 498 residues is composed of four domains (see Fig. 2a). Adjacent C-domains form the C-C or “small” interface, and bordering A-domains form the A-A or “large” interface. The B-domain acts as a mobile lid at one end of the (α/β)8-barrel A-domain, and the active site lies in the cavity between them.

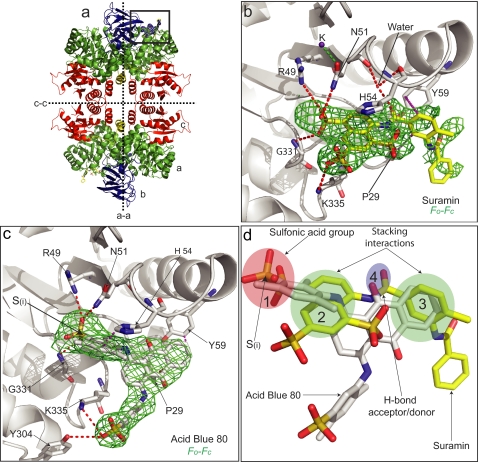

FIGURE 2.

Structures of LmPYK-suramin and LmPYK-AB80 complexes. a, the LmPYK-suramin tetramer in which the domains have been colored to aid identification (green, A domain; blue, B domain; red, C domain; yellow, N-domain). b, enlargement of the active site of the LmPYK-suramin structure. Suramin is shown by cyan sticks and corresponds primarily to one symmetrical half of the suramin molecule. The position of the suramin molecule is shown by an unbiased Fo − Fc electron density map contoured at 2 σ (orange). A K+ ion is shown as a purple sphere. c, AB80 bound in the active site of LmPYK. The AB80 molecule is shown with an unbiased Fo − Fc electron density map contoured at 2.5 σ (green). d, the LmPYK-AB80 monomer (colored gray) superposed onto the LmPYK-suramin structure (colored yellow); the orientation is identical to that of panel c. Overlapping binding characteristics of the sulfono group-containing molecules highlight key groups required for inhibitor binding; for clarity, only suramin and AB80 are shown. The four key binding characteristics observed in the LmPYK and TcPYK sulfonic acid structures are highlighted with colored ellipses as described previously in the legend for Fig. 1: site S1, pink ellipse, a sulfono group (S(i)) is observed bound in a near identical position in all complexes; site S2, green ellipse, a stacking interaction with His-54 is conserved in all structures; site S3, green ellipse, a second stacking interaction with Tyr-59 and Pro-29 is observed for suramin, Ponceau S, and AB80; site S4, blue ellipse, a hydrogen bound acceptor/donor is also commonly observed. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed red lines, and stacking interactions are shown as dashed purple lines.

Here we report the x-ray structures of four chemically related dye-like molecules including suramin in complex with L. mexicana or Trypanosoma cruzi PYKs. These structures all share similar binding modes, overlapping with the site of the adenine ring of ADP/ATP at the active site. The structural data in combination with detailed biochemical studies of the interaction of suramin with three human PYK isoenzymes and with two parasite PYKs improve our understanding of the polypharmacology of suramin (7) and provide potential scaffolds for the development of more potent isoform-specific analogues. The structures provide an interesting link to Ehrlich's groundbreaking work over a century ago and show one way in which the phenylsulfonate dyes used in the original work interact with a trypanosomatid protein. Indeed, despite the ubiquitous use of such dyes as biological markers and the uninterrupted use of suramin as a prescription drug since 1916, there has previously been very little information on the nature of the interactions of this important class of phenylsulfonates with biological macromolecules. The structural and binding data presented here are consistent with the phenylsulfonate moieties acting as adenosine analogues.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression, Purification, Crystallization, and Data Collection

LmPYK was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously (20), and TcPYK was overexpressed in E. coli and purified as described (see supplemental text T1). Purified LmPYK and TcPYK samples (30 mg ml−1 in 20 mm triethanolamine-HCl buffer (pH 7.2)) were diluted to 7–15 mg ml−1 using 20 mm triethanolamine-HCl buffer (pH 7.2). For co-crystallization experiments, the following concentrations of ligands were added to the protein sample: (a) LmPYK-1,3,6,8-pyrenetetrasulfonic (PTS) acid (1 mm, final concentration is 0.5 mm in the crystallization drop) and suramin (2 mm, final concentration is 1 mm in the crystallization drop); (b) LmPYK-acid blue 80 ((LmPYK-AB80) ∼250 μm, based upon 40% purity, final concentration is ∼125 μm in the crystallization drop); (c) LmPYK-benzothiazole-2,5-disulfonic acid (1 mm, final concentration is 0.5 mm in the crystallization drop); (d) LmPYK-Ponceau S and LmPYK-acid blue 25 (1 mm Ponceau S and 500 μm acid blue 25 (based on 50% purity), the final concentration in the crystallization drop is 500 and 250 μm, respectively); and (e) TcPYK-Ponceau S (1 mm, final concentration is 0.5 mm in the crystallization drop). Crystals of both LmPYK and TcPYK complexes were obtained at 4 °C by vapor diffusion using the hanging drop technique. The drops were formed by mixing 1.5 μl of protein solution with 1.5 μl of a well solution, composed of 7–16% PEG 8000, 20 mm triethanolamine-HCl buffer (pH 7.2), 50 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, and 10–25% glycerol. The drops were equilibrated against a reservoir filled with 0.5 ml of well solution. Crystals grew to maximum dimensions after 1 week. Prior to data collection, crystals were equilibrated for 14 h over a well solution composed of 9–14% PEG 8000, 20 mm triethanolamine-HCl buffer (pH 7.2), 50 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, and 25% glycerol, which eliminated the appearance of ice rings. Intensity data were collected (ϕ scans were 0.2° over 100°) at the Diamond synchrotron radiation facility in Oxfordshire, UK on beamline IO3 from a single crystal flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen at −17 °C. Data were then processed with MOSFLM (21) and scaled with SCALA (22).

Structure Determination

The LmPYK structures were solved by molecular replacement using the program PHASER (23). A monomer from the previously determined tetrameric structure of LmPYK ((1PKL (24)) was divided into two search regions. Region 1 (residues Pro-87–Pro-187, which is equivalent to a complete B-domain) and region 2 (residues 1–86, 188–481, and 489–498) served as search models. The resulting model was divided into three rigid body domains (B-domain = 87–187, A-domain = 1–86 and 187–356, C-domain = 358–498) and subjected to 10 cycles of rigid body refinement using the program REFMAC (25). The TcPYK-Ponceau S structure was solved using an identical method to that of LmPYK, and the sequence was adjusted using COOT to correspond with the published TcPYK amino acid sequence (accession number EFZ25721.1). When appropriate, ligands and water molecules were added to the models. Models were then subjected to cycles of restrained refinement with manual adjustments to ligands and side chains using the program COOT (26). Figures were generated using PyMOL (27). A more detailed description of the refinement processes for each of the different LmPYK and TcPYK crystal structures can be found in the supplemental material.

The atomic coordinates of the LmPYK-PTS/suramin (3PP7), LmPYK-AB80 (3QV6), LmPYK-BDS (3QV8), LmPYK-Ponceau S (3QV7), and the TcPYK-Ponceau S (3QV9) complexes have been submitted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Superpositions of PYK structures were performed using both PyMOL and CCP4 superpose (27, 28).

Suramin Inhibition Assays

LmPYK inhibition was monitored by either a luciferase (as described previously (29)) or a lactate dehydrogenase-coupled assay.3 For the lactate dehydrogenase assay, the following was added to a 1-ml cuvette: 780 μl of assay mix (1× assay buffer (50 mm triethanolamine buffer, pH 7.2, 100 mm KCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol), 0.2 mm NADH (Roche Applied Science, 128023), 3.2 units/ml lactate dehydrogenase (Sigma, 61309)), 1.6 units/ml LmPYK (one unit will convert 1.0 μmol of P-enolpyruvate to pyruvate per min at pH 7.0 at 25 °C in the absence of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate (F26BP)), 10% DMSO, and 200 μl of an inhibitor solution (made up with 1× assay buffer and 10% DMSO). The mixture was incubated for 5 min before the reaction was started by the addition of 20 μl of 20 mm P-enolpyruvate and 10 mm ADP (final concentration = 0.4 mm P-enolpyruvate (Sigma, 79430) and 0.2 mm ADP (Sigma, A4386), made up with 1× assay buffer and 10% DMSO). The substrate concentrations used for the inhibitor assay were subsaturating, unlike in the standard activity assay in which 2.5 mm P-enolpyruvate and 2.0 mm ADP are used (30). The mixture was gently agitated, and the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was measured for 2 min (using LAMBDA Bio, PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

The initial rate was then calculated using the UV kinlab software module. A control rate with no inhibitor present was also determined. The rate for each inhibitor assay was expressed as a percentage of the control assay. Despite considerable light absorbance at 340 nm resulting from high concentrations of suramin (>100 μm), the data still showed inhibition of 22 and 40% at 50 and 100 μm concentrations, respectively. Ki values were calculated using the IC50-to-Ki server (31). The results provided are for competitive inhibition with ADP using the following parameters: for LmPYK and TcPYK, [E] = 0.1 nm, [SADP] = 0.1 mm, Km(ADP) = 0.26 mm, IC50 = 160 μm for LmPYK and 150 μm for TcPYK; for human PYKs (hPYKs), [E] = 0.1 nm, [SADP] = 0.1 mm, Km(ADP) = 0.1 mm, IC50 = values shown in Fig. 3, c and d. IC50 values were determined by fitting the data to Equation 1 (a four-parameter logistic model) using the KaleidaGraph version 3.6 software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

where a is the maximum response; b, is the baseline response; c is the drug concentration that provokes a response halfway between baseline and maximum; and d is the slope. The concentrations of PYK samples were determined at A280 using ϵ = 20480 m−1 cm−1. Suramin was screened against lactate dehydrogenase in the absence of PYK to avoid a false positive.

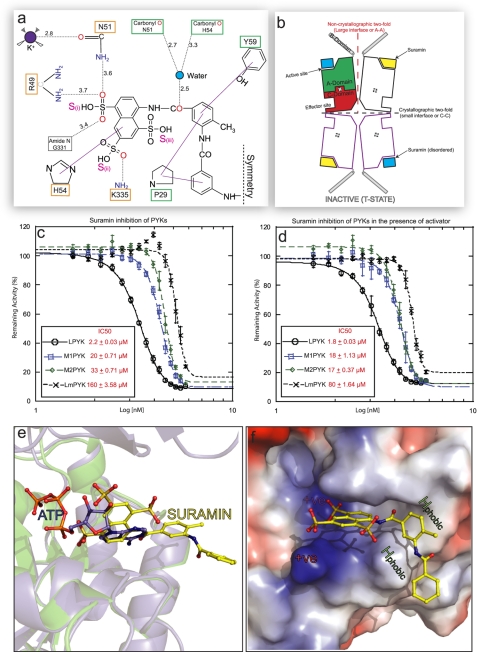

FIGURE 3.

Suramin inhibition of PYK is enhanced in the presence of the activator molecule. a, a schematic drawing showing the interatomic distances (given in Å, dotted black lines) for the interactions shown in Fig. 2b). The solid purple lines indicate stacking interactions. Residues involved in ATP binding (orange box) and not involved (green) have been indicated. Only one symmetrical half of the suramin molecule is shown (as indicated by the dashed symmetry line). b, schematic representation of the inactive LmPYK-suramin structure. Suramin is unambiguously (yellow lozenges) bound to one of the chains in the asymmetric unit (two chains outlined in black) but is disordered (blue square) in the adjacent chain, separated by the large (A-A) interface. A crystallographic two-fold axis running along the small interface generates two more chains (purple outlines), forming the biologically relevant tetramer structure. See Ref. 20 for schematics of the enzyme in its other conformations. c and d, concentration-response curves observed for the titration of suramin against PYK activity in the absence (c) and presence (d) of activator (F16BP for human PYKs, F26BP for LmPYK), using a luciferase-based assay. The values are expressed ± S.D. Suramin showed no inhibition in the control assay of luciferase activity alone. All assays were performed in triplicate. e, the binding of suramin prevents ADP/ATP binding in trypanosomatid PYKs. The R-state LmPYK-ATP/oxalate/F26BP monomer (colored blue, PDB ID = 3HQP) was superposed onto the inactive LmPYK-suramin structure (colored green). The A- and C-domains (residues 18–86 and 188–480) of both structures were superposed (r.m.s. fit of the C-α atoms of domains A and C is 0.50 Å). The superpositions of the ATP and suramin molecules clash, indicating a clear mechanism of competitive inhibition. f, the electrostatic surface of the suramin binding site, showing areas of positive charge (blue), which interact with the negatively charged sulfono groups of suramin. Two hydrophobic groups (Pro-29 and Tyr-59) provide further stability, helping to hold the molecule in the ATP/ADP binding site.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of Phenyl Sulfonate Dye-like Molecules as Ligands of Trypanosomatid PYKs

An analysis of the ATP binding sites observed in the x-ray structures of PYKs from a number of different species showed conserved positions for bound sulfate ions (32), corresponding to the phospho positions of ATP bound to R-state LmPYK (20). A pharmacophore-searching approach was used as a drug discovery strategy to identify small molecules with a similar distribution of charged groups. Searching the small-molecule database EDULISS (33) of ∼5 million compounds identified a series of sulfono group-containing molecules, many of which are reminiscent of trypan blue and other trypanocidal azo dyes used in Ehrlich's original mouse experiments (1) (Fig. 1). One particular family of acid blue compounds selected by the search (e.g. acid blue 120, 129, and 161) has a substructure similar to Cibacron blue (Fig. 1f), which has previously been used to purify PYKs by affinity chromatography (34). Co-crystallization studies of four of the molecules identified in the search (Fig. 1, b–e) are described below. The designed synthesis of the drug suramin in 1916 was based on the molecular scaffold of the trypan blue series. We therefore asked the question whether LmPYK (which has 74% sequence identity with T. brucei PYK (TbPYK)) would also bind suramin.

Trypanosomatid PYKs Co-crystallized with Phenyl Sulfonate Dye-like Molecules Adopt Inactive Conformations

Co-crystallization trials of LmPYK with trypan blue (Fig. 1a) yielded only microcrystals; however, trials with AB80 (Fig. 1e) resulted in crystals that diffracted to 2.85 Å resolution. One of the smaller sulfono group compounds, benzothiazole-2,5-disulfonic acid (BDS, Fig. 1b), was also successfully co-crystallized. In addition, both TcPYK and LmPYK were crystallized in the presence of the diazo dye, Ponceau S (a stain commonly used for the reversible staining of protein bands on nitrocellulose membranes) (Fig. 1d). LmPYK in the presence of 1 mm suramin (Fig. 1c) yielded poor quality crystals that diffracted weakly to a resolution of 5–7 Å and contained at least one exceptionally long (>700 Å) cell edge, similar to that seen for the LmPYK-F26BP complex (20). The addition of 1,3,6,8-pyrenetetrasulfonic acid has been shown to improve the LmPYK crystal quality by providing a helpful non-covalent cross-link within the crystal lattice (35), and 0.2 mm PTS was therefore included in the crystallization conditions with suramin. The structure of the LmPYK, PTS, and suramin complex was determined at 2.35 Å resolution (see Table 1 for data collection and refinement statistics). See supplemental text T2 and supplemental Fig. S4 for more detailed descriptions of the sulfonic acid complexes.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parentheses are for highest resolution shell.

| LmPYK-suramin | LmPYK-AB80 | LmPYK-BDS | LmPYK-Ponceau Sa | TcPYK-Ponceau S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | I222 | C2 | I222 | C2 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 123.8, 129.5, 165.8 | 130.1, 127.5, 118.2 | 120.6, 131.3, 167.6 | 182.1, 164.8, 123.4 | 113.2, 121.83, 96.54 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 116.2, 90.0 | 90.0,90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 115.8, 90.0 | 90.0, 109.81, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.35 | 2.85 | 2.45 | 2.70 | 2.1 |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.8 (35.2) | 8.3 (54.1) | 9.4 (56.2) | 12.3 (54.2) | 9.2 (47.9) |

| I/σI | 22.0 (4.5) | 11.8 (2.5) | 14.7 (4.6) | 10.2 (2.1) | 9.4 (2.4) |

| % of completeness | 98.2 (96.9) | 98.3 (97.6) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.6 (99.0) | 98.2 (88.6) |

| Redundancy | 6.5 (6.5) | 4.6 (4.5) | 7.3 (7.5) | 3.7 (3.5) | 6.3 (3.9) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 44.7–2.35 | 86.1–2.85 | 103.4–2.45 | 21.1–2.7 | 53.2–2.1 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 19.1/23.1 | 23.5/26.7 | 23.4/26.6 | 21.5/24.4 | 19.8/24.9 |

| No. of atoms | |||||

| Protein | 7530 | 6745 | 6775 | 13502 | 6863 |

| Ligands | 72 | 85 | 33 | 199 | 128 |

| K+ | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 2 |

| Water | 433 | 106 | 210 | 652 | 464 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||||

| Protein | 40.5 | 72.5 | 52.1 | 45.0 | 31.0 |

| Active site ligandb | 106.8 | 67.9 | 92.9 | 43.5 | 29.9 |

| Water | 39.6 | 61.7 | 46.2 | 36.3 | 35.1 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 1.69 | 0.87 | 1.26 | 0.86 | 1.92 |

| Ramachandran | |||||

| Allowed (%) | 97.0 (952/981) | 97.3 (853/877) | 96.4 (849/882) | 97.7 (1737/1778) | 96.9 (865/893) |

| Generous (%) | 99.8 (979/981) | 99.8 (875/877) | 99.8 (880/882) | 99.8 (1774/1778) | 99.8 (891/893) |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.2 (2/981) | 0.2 (2/877) | 0.2 (2/882) | 0.2 (4/1778) | 0.2 (2/893) |

a LmPYK-Ponceau S was crystallized in the presence of acid blue 25 (see supplemental text T1 and supplemental Figure S4).

b B-factors are for ligands bound to the active site in a similar manner.

The A- and C-domains (residues 18–86 and 188–480) of the LmPYK-PTS/suramin, LmPYK-AB80, and LmPYK-BDS tetramers were superimposed onto the inactive LmPYK 1PKL (24) structure (chains E, F, G, and H), resulting in r.m.s. fits for all Cα atoms of 0.83, 0.96, and 0.76 Å, respectively, indicating that all sulfonic acid complexes were in a similar inactive (T-state) conformation (20).

Suramin, AB80, Ponceau S, and BDS Binding Sites Overlap with the ATP Sites of Trypanosomatid PYKs

Within the complex (LmPYK-PTS/suramin), electron density for suramin was observed in both active sites of the asymmetric unit, although only one of the two monomers exhibited strong and unambiguous difference density, which could be modeled as the naphthalene-1,3,5-trisulfonic acid group of one-half of the symmetrical suramin molecule (Fig. 2b), with the remaining disordered portion pointing outward toward the solvent. The interactions between the naphthalene-1,3,5-trisulfonic acid group of suramin and the A-domain of LmPYK are shown in Fig. 3a. A comparison of suramin binding with that of ATP binding observed in LmPYK-ATP/oxalate/F26BP (PDB ID = 3HQP) (Fig. 3e) shows that the two ligand binding sites overlap. Although Fo − Fc electron density was observed in both active sites, only suramin bound to chain A was well defined. In the active site of chain B, the Fo − Fc electron density was ambiguous, indicating that suramin may be bound in more than one conformation. Of the three negatively charged sulfono groups of suramin bound to the active site, only two provide hydrogen-bond interactions (Fig. 3a), although there is a general area of positive charge surrounding the sulfono groups within the binding cleft (Fig. 3f). LmPYK forms a single interaction with the sulfono group (ii) through Lys-335 (Fig. 3a), but the majority of interactions involve the sulfono group (i), through three hydrogen bonds. In addition, His-54 stacks above the ring system of the naphthalene-1,3,5-trisulfonic acid group with the NH group of the side chain pointing toward the sulfono group (ii). The remaining hydrophobic ring of suramin is held in place through stacking interactions with Pro-29 and Tyr-59 (Fig. 3a), found outside the deep binding cleft (Fig. 3f).

Within the LmPYK-AB80 structure, only the active site of one of the two monomers exhibited strong and unambiguous difference (Fo − Fc) density corresponding to one complete AB80 molecule (Fig. 2c). B-factors for the AB80 molecule were similar to those observed for the protein (Table 1). In the LmPYK-BDS structure, Fo − Fc electron density corresponding to the BDS molecule was clear (supplemental Fig. S2), and the BDS molecule was clearly observed in all active sites within the asymmetric unit. Ponceau S was bound in near identical positions within the active sites of both LmPYK and TcPYK (Fig. 1d and supplemental Fig. S2d), with the sulfono groups bound to site S1 occupying a similar position to that observed in all other structures described (Fig. 1, pink ellipse).

The four conserved ligand recognition features observed in the structures are highlighted in Figs. 1 and 2d by shaded ellipses. In site S1, a sulfono group (indicated by S(i)) mimics the α-phospho group of ATP, forming at least one hydrogen bond. In site S2, an aromatic ring system stacks above His-54. In site S3, aromatic rings form stacking interactions with Pro-29 and/or Tyr-59. In site S4, a hydrogen bond acceptor or donor forms a hydrogen bond via a water to the backbone carbonyls of Asn-51 and His-54 in the suramin structure (Fig. 3a).

Suramin Binds with Up to 2-Fold Higher Affinity to Effector-bound PYKs

The strongly colored dye-like compounds AB80 and Ponceau S absorb light at wavelengths required for the available kinetic assays and make it impractical to determine IC50/Ki values accurately. For this reason, only suramin was taken forward for kinetic studies. We have measured suramin inhibition for three hPYK isoenzymes (with IC50 values of 20, 33, and 2.2 μm and Ki values of 10, 16.5, and 1.1 μm for M1, M2, and L isoenzymes, respectively) and for two trypanosomatid enzymes, LmPYK (Fig. 3c) and TcPYK (supplemental Fig. S3) (with IC50 and Ki values of ∼155 and 112 μm, respectively). To confirm these results, LmPYK inhibition was also monitored by an unrelated lactate dehydrogenase-based assay, which gave very similar results (supplemental Fig. S3).

The natural effector for hM2PYK and hLPYK is fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (F16BP), whereas the effector for LmPYK is F26BP (36–38). We observed a 2-fold reduction in the Ki value for suramin when effector is present for both hM2PYK (Ki decreases from 16.5 ± 0.4 to 8.5 ± 0.2 μm) in the presence of F16BP and LmPYK (Ki decreases from 115.6 ± 2.6 to 57 ± 1.2 μm) in the presence of F26BP. The presence of F16BP has no measurable effect on the Ki values of hLPYK (∼1 μm) and hM1PYK (∼9.5 μm) (Fig. 3d). The latter result is perhaps expected as hM1PYK is constitutively active and not regulated by occupancy of the effector site.

LmPYK-PTS/suramin is in the inactive conformation, which is inherently flexible when compared with that of the more rigid effector-bound active conformer, locked by the F26BP effector molecule (LmPYK-F26BP (20)). The flexibility of the inactive conformation is likely to contribute to the differential binding of suramin to the active sites (Fig. 3b). The relationship between enzyme flexibility and differential binding of active-site ligands has also been observed for oxalate and ATP binding in the absence of the effector molecule (20, 39), whereby ATP is either completely absent or bound in a different position within the active site. When the enzyme is stabilized by the effector molecule, it is inherently more rigid and adopts the optimal conformation for binding substrates. It is only within this rigidified effector-bound structure that all active-site components occupy near identical positions within all four active-site clefts of the PYK tetramer (20). The difference in conformational flexibility between effector-bound and unbound states also provides an explanation for the different Ki values observed for oxalate inhibition of human M2PYK, in the presence (Ki = 24 μm) and absence (Ki = 220 μm) of the effector molecule (37).

Consideration of in vivo conditions in human serum has important implications for PYK inhibitors acting like suramin. The binding affinity for suramin is lower (Ki = 1–17 μm) when compared with that measured for the natural substrate ADP (100 μm (40)). Furthermore, the ADP concentration in which PYK operates in vivo is ∼50 μm (total cytosolic ADP = 300 μm (41) and free cytosolic ADP = 50 μm (42)), but suramin can achieve serum levels as high as 352 μm (43) and cellular levels (in certain compartments) in excess of 150 μm (44). Moreover, effector-bound PYK is a better representation of in vivo conditions as effector levels are likely to be saturating in trypanosomatids (where F26BP concentration = 15–50 μmol/g of protein (∼85 μm) (45)) and in human cells (where F16BP concentration can reach 5 mm in cancer cells but is only 50 μm in non-cancerous cells (46)). The tighter binding found for both suramin and oxalate inhibitors in the presence of effector suggests that inhibitor assays for allosterically regulated forms of PYK should be carried out in the presence of effector.

Mode of Action of Suramin-like Phenyl Sulfonates

Suramin is known to interact with a diversity of targets, but x-ray crystal structures of suramin-target protein complexes have been determined for only five proteins (supplemental Table S1), three of which are enzymes. None of these enzymes binds ATP/ADP, which is unexpected as the chemotherapeutic effects of suramin are often attributed to its ability to inhibit the binding of ATP and other nucleotides (47). There is evidence to show that the trypanocidal action of suramin results from the inhibition of ATP production by glycolysis (48), an enzymatic pathway that has evolved to bind phosphometabolites. Although the binding mode has previously remained elusive, it is not surprising that suramin and the chemically related AB80 and BDS molecules are found to occupy ADP/ATP binding sites, which are present in many glycolytic enzymes, and may explain the promiscuous behavior of this compound class.

To examine binding modes, the LmPYK-PTS/suramin, LmPYK-PTS/AB80, and LmPYK-PTS/BDS monomers (residues 18–86 and 188–480, excluding the B-domain) were superposed onto the LmPYK-ATP/oxalate/F26BP (PDB ID = 3HQP) structure, with an r.m.s. fit for the Cα atoms of the A- and C-domain core of 0.50 Å. It is clear from Fig. 3e that suramin occupies the adenosine binding site and blocks ADP/ATP binding. Similar positions are observed for AB80, Ponceau S, and BDS binding (supplemental Fig. S2c). In all PYK structures presented here, the adenine and ribose positions overlap with the dye molecules, but only the interactions of the α-phospho group are mimicked by one of the sulfono groups. The x-ray structure shows that the bulk of the suramin ring system sterically hinders the molecule from penetrating further into the active-site cleft and occupying the β and γ ATP-phospho positions. The adenine moiety actually makes very few interactions with LmPYK (20), in part explaining the relatively weak Ki value (Ki = 116 μm) and high B-factor (∼100 Å2) of suramin. Both AB80 (Fig. 2d) and Ponceau S (supplemental Fig. S2d) show stronger electron density and bind in a similar position to that of suramin, with key groups providing identical interactions with the protein (Fig. 1). The residues involved in suramin, AB80, Ponceau S, BDS, and ATP/ADP binding in LmPYK are all fully conserved in both T. brucei and T. cruzi PYKs (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that suramin would also inhibit both these PYKs. This was confirmed using the lactate dehydrogenase-linked enzyme assay, whereby TcPYK was shown to be inhibited by suramin with an IC50 of 150 μm (supplemental Fig. S3). It is noteworthy that all the ligands described here share common characteristics and can all be adequately superimposed onto the structure of suramin (Fig. 1f). It may therefore be hypothesized that all the molecules are likely to bind to similar protein binding sites, which indeed appears to be the case for LmPYK.

The Trypanosomatid PYK Complexes Provide a Template for Inhibitor Design

Affinity values for suramin inhibition are noticeably different for human (Ki values are 10.0, 16.5, and 1.1 μm for M1PYK, M2PYK, and LPYK, respectively) and parasite (Ki value for LmPYK and TcPYK = ∼112 μm) PYKs. Such differences in ligand affinities suggest that it may be possible to exploit the amino acid differences around this suramin/dye binding pocket (supplemental Fig. S2b) to design and develop species-specific small-molecule inhibitors. The efficacy of inhibitors could be further enhanced by the concomitant use of PYK activators (Fig. 3, c and d). The very different activation mechanisms of LmPYK and hM2PYK tetramers (20, 49) may provide another handle for designing species-specific inhibitors. For LmPYK, the allosteric T- to R-state switch is characterized by a rigid body rotation of the A- and C-domains, which are locked in the active state by effector binding. This contrasts with the T- to R-state switch for hM2PYK, which involves a switch from inactive dimer to active F16BP-stabilized tetramer.

Suramin has been shown to accumulate in acidic compartments of mammalian cell lines reaching levels >150 μm (44), which is above the Ki for all effector-bound PYKs. It is also noteworthy that although both human and trypanosomal PYKs are inhibited by suramin, a clear cell uptake/entry mechanism for this highly charged molecule remains controversial. It is thought that suramin uptake in trypanosomatids occurs via receptor-mediated endocytosis and is not principally mediated via a lipoprotein-specific receptor as initially proposed, but by an as yet unidentified receptor (50). The fact that suramin-like dye molecules bind in a similar manner to both TcPYK and LmPYK is also of potential importance as this is the first demonstration of a molecule possessing cross-reactivity against similar trypanosomatid targets and highlights the potential of creating a general trypanosomatid inhibitor. It is now over 100 years since the discovery of the trypanocidal effects of azo dyes and the subsequent development of suramin (51). The structural and kinetic results presented in this study show one aspect of its remarkable polypharmacology and provide a template for the design of new generations of inhibitors with improved specificity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Hee-won Park, Structural Genomics Consortium, University of Toronto, Canada for the gift of human PYK isoenzymes and Dr. J. Dornan for excellent advice and practical help. We also thank the staff at the synchrotron facilities at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) and Diamond synchrotron radiation facility and also at the National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD. The Centre for Translational and Chemical Biology and the Edinburgh Protein Production Facility were funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

This work was authored, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health staff. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and by the European Commission through its International Cooperation with Developing Countries program.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3PP7, 3QV6, 3QV8, 3QV7, and 3QV9) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text, Table S1, and Figs. S1–S4.

Assay mix and working stocks of ligands (including inhibitor dilution series) were made fresh on the same day the assays were performed.

- PYK

- pyruvate kinase

- LmPYK

- L. mexicana PYK

- TcPYK

- T. cruzi PYK

- LPYK

- human liver PYK isoenzyme

- M1PYK

- human muscle PYK isoenzyme

- M2PYK

- human embryonic/tumor PYK isoenzyme

- F16BP

- fructose 1,6-bisphosphate

- F26BP

- fructose 2,6-bisphosphate

- BDS

- benzothiazole-2,5-disulfonic acid

- PTS

- 1,3,6,8-pyrenetetrasulfonic acid

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- h

- human.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ehrlich P., Shiga K. (1904) Berlin Klin. Wochenschrift 20, 329–362 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawking F. (1978) Adv. Pharmacol. Chemother. 15, 289–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. La Rocca R. V., Stein C. A., Danesi R., Myers C. E. (1990) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 893–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahoney C. W., Azzi A., Huang K. P. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5424–5428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitsuya H., Popovic M., Yarchoan R., Matsushita S., Gallo R. C., Broder S. (1984) Science 226, 172–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Voogd T. E., Vansterkenburg E. L., Wilting J., Janssen L. H. M. (1993) Pharmacol. Rev. 45, 177–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGeary R. P., Bennett A. J., Tran Q. B., Cosgrove K. L., Ross B. P. (2008) Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 8, 1384–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. (1997) Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 23, 3–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freissmuth M., Boehm S., Beindl W., Nickel P., Ijzerman A. P., Hohenegger M., Nanoff C. (1996) Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 602–611 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klinger M., Freissmuth M., Nickel P., Stäbler-Schwarzbart M., Kassack M., Suko J., Hohenegger M. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 55, 462–472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braga-Silva L. A., dos Santos A. L., Portela M. B., Souto-Padrón T., de Araújo Soares R. M. (2007) FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51, 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Clercq E. (2009) Med. Res. Rev. 29, 571–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baghdiguian S., Fantini J. (1997) Cancer J. 10, 31–37 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Misset O., Opperdoes F. R. (1987) Eur. J. Biochem. 162, 493–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willson M., Callens M., Kuntz D. A., Perié J., Opperdoes F. R. (1993) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 59, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jagielski A. K., Kryśkiewicz E., Bryła J. (2006) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 537, 205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Opperdoes F. R. (1987) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41, 127–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drew M. E., Morris J. C., Wang Z., Wells L., Sanchez M., Landfear S. M., Englund P. T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46596–46600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albert M. A., Haanstra J. R., Hannaert V., Van Roy J., Opperdoes F. R., Bakker B. M., Michels P. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28306–28315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgan H. P., McNae I. W., Nowicki M. W., Hannaert V., Michels P. A., Fothergill-Gilmore L. A., Walkinshaw M. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12892–12898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Potterton E., Briggs P., Turkenburg M., Dodson E. (2003) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Evans P. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rigden D. J., Phillips S. E., Michels P. A., Fothergill-Gilmore L. A. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 291, 615–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 28. Potterton E., McNicholas S., Krissinel E., Cowtan K., Noble M. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1955–1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang J. K., Boxer M. B., Vander Heiden M. G., Shen M., Skoumbourdis A. P., Southall N., Veith H., Leister W., Austin C. P., Park H. W., Inglese J., Cantley L. C., Auld D. S., Thomas C. J. (2010) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 3387–3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hannaert V., Yernaux C., Rigden D. J., Fothergill-Gilmore L. A., Opperdoes F. R., Michels P. A. (2002) FEBS Lett. 514, 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cer R. Z., Mudunuri U., Stephens R., Lebeda F. J. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W441–W445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tulloch L. B., Morgan H. P., Hannaert V., Michels P. A., Fothergill-Gilmore L. A., Walkinshaw M. D. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383, 615–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsin K. Y., Morgan H. P., Shave S. R., Hinton A. C., Taylor P., Walkinshaw M. D. (2011) Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D1042–D1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Subramanian S. (1984) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 16, 169–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morgan H. P., McNae I. W., Hsin K. Y., Michels P. A., Fothergill-Gilmore L. A., Walkinshaw M. D. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66, 215–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valentini G., Chiarelli L. R., Fortin R., Dolzan M., Galizzi A., Abraham D. J., Wang C., Bianchi P., Zanella A., Mattevi A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23807–23814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dombrauckas J. D., Santarsiero B. D., Mesecar A. D. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 9417–9429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ernest I., Callens M., Opperdoes F. R., Michels P. A. (1994) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 64, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larsen T. M., Benning M. M., Rayment I., Reed G. H. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 6247–6255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boxer M. B., Jiang J. K., Vander Heiden M. G., Shen M., Skoumbourdis A. P., Southall N., Veith H., Leister W., Austin C. P., Park H. W., Inglese J., Cantley L. C., Auld D. S., Thomas C. J. (2010) J. Med. Chem. 53, 1048–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Veech R. L., Lawson J. W., Cornell N. W., Krebs H. A. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 6538–6547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Akerboom T. P., Bookelman H., Zuurendonk P. F., van der Meer R., Tager J. M. (1978) Eur. J. Biochem. 84, 413–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. La Rocca R. V., Cooper M. R., Stein C. A., Kohler D., Uhrich M., Weinberger E., Myers C. E. (1992) Ann. Oncol. 3, 571–573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang S. S., Koh H. A., Huang J. S. (1997) FEBS Lett. 416, 297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Van Schaftingen E., Opperdoes F. R., Hers H. G. (1987) Eur. J. Biochem. 166, 653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eigenbrodt E., Reinacher M., Scheefers-Borchel U., Scheefers H., Friis R. (1992) Crit. Rev. Oncog. 3, 91–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Avliyakulov N. K., Lukes J., Kajava A. V., Liedberg B., Lundström I., Svensson S. P. S. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 1723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fairlamb A. H., Bowman I. B. R. (1980) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1, 315–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ashizawa K., Willingham M. C., Liang C. M., Cheng S. Y. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16842–16846 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pal A., Hall B. S., Field M. C. (2002) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122, 217–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kleine F. K., Fischer W. (1922) Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 48, 1693–1696 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.