Abstract

The Timothy syndrome mutations G402S and G406R abolish inactivation of CaV1.2 and cause multiorgan dysfunction and lethal arrhythmias. To gain insights into the consequences of the G402S mutation on structure and function of the channel, we systematically mutated the corresponding Gly-432 of the rabbit channel and applied homology modeling. All mutations of Gly-432 (G432A/M/N/V/W) diminished channel inactivation. Homology modeling revealed that Gly-432 forms part of a highly conserved structure motif (G/A/G/A) of small residues in homologous positions of all four domains (Gly-432 (IS6), Ala-780 (IIS6), Gly-1193 (IIIS6), Ala-1503 (IVS6)). Corresponding mutations in domains II, III, and IV induced, in contrast, parallel shifts of activation and inactivation curves indicating a preserved coupling between both processes. Disruption between coupling of activation and inactivation was specific for mutations of Gly-432 in domain I. Mutations of Gly-432 removed inactivation irrespective of the changes in activation. In all four domains residues G/A/G/A are in close contact with larger bulky amino acids from neighboring S6 helices. These interactions apparently provide adhesion points, thereby tightly sealing the activation gate of CaV1.2 in the closed state. Such a structural hypothesis is supported by changes in activation gating induced by mutations of the G/A/G/A residues. The structural implications for CaV1.2 activation and inactivation gating are discussed.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Calcium Channels, Genetic Diseases, Kinetics, Protein Conformation, Activation Determinants, Channel Gating, Inactivation, Timothy Syndrome

Introduction

Timothy syndrome (TS),3 an autosomal dominant disorder, arises from two de novo missense mutations, G402S and G406R, in CaV1.2 calcium channels. This channelopathy manifests itself clinically in physical, neurological, and developmental defects and autism spectrum disorders. G406R additionally causes syndactyly (1). Functional studies have shown that TS mutations G402S and G406R dramatically reduce voltage-dependent channel inactivation, resulting in sustained membrane depolarization and increased calcium entry during an action potential (1). The resulting prolongation of the QT interval can induce severe arrhythmias causing sudden death in early childhood (1). Kinetic modeling studies suggested that the increased action potential duration and enhanced calcium entry may be associated with delayed after-depolarizations in cardiac myocytes (2).

A role of G406R in calcium-dependent inactivation was established by Raybaud et al. (3) and Barrett and Tsien (4). Systematic mutations of Gly-436 in rabbit CaV1.2 (corresponding to Gly-406 in the human CaV1.2) to Ala, Pro, Tyr, Glu, Arg, His, Lys, or Asp all substantially slow channel inactivation (3). A large number of amino acids involved in Ca2+ channel inactivation have been identified, and several molecular mechanisms for this process have been proposed (5–7).

We have previously shown that mutations in the lower third of S6 segments in CaV1.2 in most cases shift the channel inactivation and activation in a coupled manner. This is evident from similar shifts of channel activation and inactivation curves (8, 9), suggesting a serial gating scheme (R)est→(O)pen→(I)nactivated where a shift in R → O transitions would automatically shift the inactivation curve. However, Raybaud et al. (3) reported that mutations of the TS Gly-436 that suppressed inactivation in CaV1.2 induced only minor changes in activation gating.

The functional impact and structural basis of amino acid substitutions of the TS Gly-432 (corresponding to Timothy Gly-402 in human CaV1.2) are less understood. Our homology model suggests that Gly-432 forms part of a conserved group of small amino acids, Gly-432(IS6), Ala-780(IIS6), Gly-1193(IIIS6), and Ala-1503(IVS6), near the inner channel mouth of CaV1.2 (Fig. 1), which we call the G/A/G/A motif. A corresponding Gly-657 in hERG (Human Ether-a-go-go related Gene) potassium channels was found to be important for close helix packing (10), and in KcsA, replacement of the corresponding small and hydrophobic Ala-108 by a polar serine or threonine (A108S/T) dramatically increased channel open probability (11, 12). Small gating-sensitive residues at this position thus seem to be essential for helix-helix interactions in a number of ion channels.

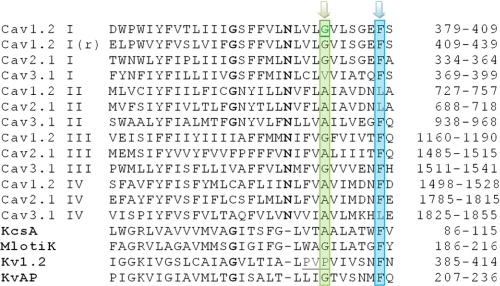

FIGURE 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of S6 helices of CaV channels with selected K+ channels. Conserved G/A/G/A residues are shaded green, and interacting phenylalanines (neighboring domains) are shaded blue. The Timothy glycine is underlined green, and the PVP motif of KV1.2 is underlined black.

To clarify the role of Gly-432 as part of the apparent G/A/G/A motif of CaV1.2, we have asked several questions. First, do mutations of the homologous small residues in the other domains, Ala-780(IIS6), Gly-1193(IIIS6), and Ala-1503(IVS6), have similar effects on channel gating to substitutions of Gly-432? Second, how do amino acid substitutions in these positions affect the link between activation and inactivation? Third, is an essential role of the G/A/G/A residues in helix packing and closed-state stability supported by functional data? Answers to these questions will help to understand the interactions of residues in the bundle crossing region and help to clarify the specific impact of pore residues on activation and inactivation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Conservation Analysis

Sequences of voltage-gated calcium channels (13) were downloaded from the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology data base (14). Sequences of all channels from Homo sapiens were used to search NCBI BLAST (blastp) (15). Initial sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW (16). Sequences of selected potassium channel crystal structures (KcsA, MthK, KvAP, Kv1.2, and MlotiK) were aligned manually with CaV channels using GENEDOC (17).

Homology Modeling

The homology model of the open CaV1.2 channels, based on the KvAP crystal structure and a NaChBac model, incorporating an insertion at the position of the conserved asparagines, was published previously (8). A model of the closed conformation using the same alignment as for the open conformation (indel at Asn) was generated using Modeller9v7 (18). The KcsA crystal structure and the NaChBac model were used as templates. Coordinates of the model can be found in the supplemental material.

Accessibility Calculations

Amino acid accessibilities were calculated using the WHAT IF webserver (19). The accessible surface area in this program is defined as the area at the Van der Waals surface that is accessible by a water molecule (1.4 Å). The units of accessible surface are Å2. Re-entrant surfaces are not considered by WHAT IF.

Mutagenesis

The CaV1.2 α1-subunit coding sequence (GenBankTM X15539) in-frame 3′ to the coding region of a modified green fluorescent protein was kindly donated by Dr. M. Grabner (20). Substitutions in segment IS6, IIS6, and IVS6 of the CaV1.2 α1-subunit were introduced using the QuikChange® Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with mutagenic primers according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mutations were introduced in segment IS6 in position 432 (G432A/S/V/N/M/W), in helix IIS6 in position 780 (A780G/N/P/T/V/W), in IVS6 in position 1503 (A1503G/P/M/N/T/V/W), and one double mutation in IS6 (G432S/S435G). All constructs were checked by restriction site mapping and sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection

Human embryonic kidney tsA-201 cells were grown at 5% CO2 and 37 °C to 80% confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's/F-12 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were split with trypsin/EDTA and plated on 35-mm Petri dishes (Falcon) at 30–50% confluence ∼16 h before transfection. Subsequently tsA-201 cells were co-transfected with cDNAs encoding wild-type or mutant CaV1.2 α1-subunits with auxiliary β2a and β2c (21) as well as α2-δ1 (22) subunits. The transfection of tsA-201 cells was performed using the FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) following standard protocols. tsA-201 cells were used until passage number 15. No variation in channel gating related to different cell passage numbers was observed.

Ionic Current Recordings and Data Acquisition

Barium currents (IBa) through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels were recorded at 22–25 °C by patch-clamping (23) using an Axopatch 200A patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City) 36–48 h after transfection. The extracellular bath solution (5mm BaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 140 mm choline chloride) was titrated to pH 7.4 with methanesulfonic acid. Patch pipettes with resistances of 1–4 megaohms were made from borosilicate glass (Clark Electromedical Instruments) and filled with pipette solution (145 mm CsCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm EGTA 10), titrated to pH 7.25 with CsOH. All data were digitized using a DIGIDATA 1200 interface (Axon Instruments), smoothed by means of a four-pole Bessel filter, and saved to disc. 100-ms current traces were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz; tail currents were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz. Leak currents were subtracted digitally using average values of scaled leakage currents elicited by a 10-mV hyperpolarizing pulse or electronically by means of an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments). Series resistance and offset voltage were routinely compensated for. The pClamp software package (Version 7.0 Axon Instruments) was used for data acquisition and preliminary analysis. Microcal Origin 7.0 was used for analysis and curve-fitting.

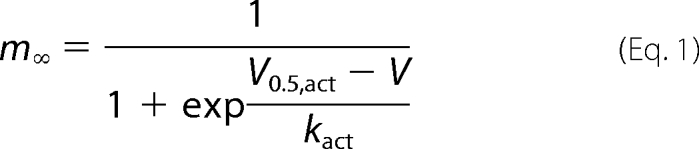

The voltage dependence of activation was determined from I-V curves and fitted to

|

The time course of current activation was fitted to a mono-exponential function, I(t) = A·exp(1/τ) + C, where I(t) is current at time t, A is the amplitude coefficient, τ is the time constant, and C is the steady-state current. Data are given as the mean ± S.E.

Calculation of Amino Acid Descriptors

Physicochemical descriptors were calculated for amino acids using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE; Version 2008.10, Chemical Computing Group, Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada) (24).

RESULTS

The “Timothy Gly-432” Is Part of a Motif of Small Residues at the Inner Channel Mouth

To analyze the degree of conservation of the TS Gly-402, a sequence alignment was performed. Sequences of the 10 different voltage-gated calcium channels genes encoded in the human genome were downloaded from the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology data base. The human sequences were used to search NCBI BLAST using the blastp program. The pore-forming segments of CaV (S5, P, S6) from different species were aligned using standard parameters in ClustalW. Fig. 1 shows the multiple sequence alignment of selected CaV channels, and the complete alignment of all human S6 segments can be found in supplemental Fig. S1. Fig. 1 shows that Gly-432 is part of a motif of small amino acids (Gly-432(IS6)-Ala-780(IIS6)-Gly-1193(IIIS6)-Ala-1503(IVS6)) at the inner channel mouth. The conservation analysis reveals that these positions either have a glycine or an alanine. The only exceptions are T-type channels, which have a valine at this position in IS6. We will refer to this structural motif of CaV as G/A/G/A.

Mutations of Gly-432 Shift the Activation Curve

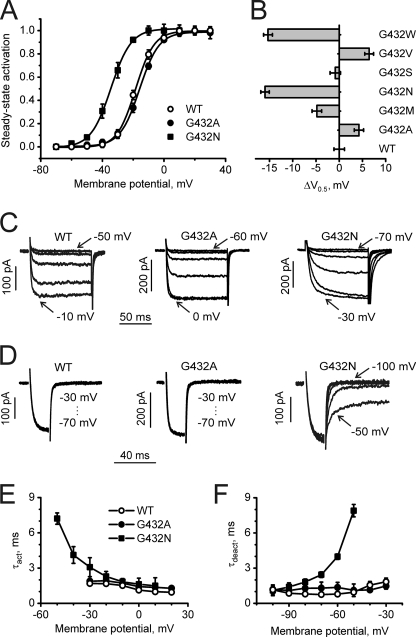

In the absence of experimentally determined structures of calcium channels, homology models have been used successfully to explain experimental data and to suggest new experiments (25–29). Our modeling data on CaV1.2 suggest that G/A/G/A plays an essential role in helix packing. In light of this hypothesis, we investigated whether replacement of Gly-432 by residues with different properties (e.g. size and hydrophobicity) would affect the voltage dependence of channel activation. Fig. 2, A and B, illustrate the corresponding effects on the steady-state activation curves. Replacement of Gly-432 by methionine, asparagine, and tryptophan shifts channel activation toward hyperpolarization. Interestingly, G432A and G432V shifted the curve to the right, suggesting a stabilization of the closed or a destabilization of the open states. Changes in activation and deactivation gating for selected mutants are illustrated by current traces shown in Fig. 2, C and D. The slowing of channel activation and deactivation (voltage dependences of activation and deactivation time constants) for G432N accompanying the leftward shift of the activation curve and fast activation/deactivation kinetics of G432A inducing a rightward shift are exemplified (Fig. 2, E and F).

FIGURE 2.

Gating changes induced by mutations of Gly-432 in segment IS6 of CaV1.2. A, averaged activation curves of wild-type (n = 9) and mutants G432A (n = 7) and G432N (n = 7) are shown. B, shown is a shift of activation curves induced by substitutions of Gly-432 by residues of different physicochemical properties. C, representative families of IBa through wild-type and the indicated mutant channels during depolarizing test pulses from −100 mV in 10-mV increments (first and last potentials are indicated) are shown. D, representative tail currents of WT and the indicated mutant channels are shown. Currents were activated during a 20-ms conditioning depolarization to −10 mV for wild type, 0 mV for G432A, and −20 mV for G432N. Deactivation was recorded during subsequent repolarizations in 10-mV increments starting from −100 mV. E, mean time constants of channel activation of WT (n = 9) and mutants G432A (n = 7) and G432N (n = 7) are plotted against test potential. F, mean time constants of channel deactivation of wild type (n = 8) and mutants G432A (n = 6) and G432N (n = 6) are plotted against test potential. Time constants were estimated by fitting current activation and deactivation to a mono-exponential function.

Substitutions of Gly-432 Remove Channel Inactivation

In contrast to the differing effects on channel activation (Fig. 2, Table 1), all mutations of Gly-432 tested reduced inactivation regardless of the properties of the new side chain. This is evident from current traces under long-lasting depolarizations for all mutants (Fig. 3). The changes in the steady-state inactivation curves for mutation to alanine (G432A) and asparagines (G432N) are exemplified in Fig. 3A. The remaining currents after 3000-ms depolarizations to the peak current voltage of the current voltage activation curves are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Pore mutations affect voltage-dependent gating of CaV1.2

Midpoints, slope factors of the activation, inactivation curves, and fractions of non-inactivated channels after a 3-s depolarization to the peak current potential of the current voltage relationship (I-V curve) are shown. Numbers of experiments are indicated in parentheses.

| Construct | V0.5 | kact | V0.5,inact | kinact | r3000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mV | mV | mV | mV | ||

| WT | −18.4 ± 0.8 (9) | 6.0 ± 0.7 | −41.5 ± 0.9 (5) | 6.4 ± 0.9 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| IS6 G432a | |||||

| G432A | −14.2 ± 0.6 (7) | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | ||

| G432M | −23.2 ± 0.6 (7) | 7.7 ± 0.6 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | ||

| G432N | −34.4 ± 0.4 (7) | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | ||

| G432S | −19.2 ± 0.7 (7) | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 0.74 ± 0.07 | ||

| G432V | −12.0 ± 0.6 (6) | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | ||

| G432W | −33.7 ± 0.6 (8) | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | ||

| IIS6 A780 | |||||

| A780G | −29.4 ± 0.6 (5) | 6.2 ± 0.6 | −54.4 ± 1.3 (4) | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.11 ± 0.06 |

| A780N | −43.8 ± 1.0 (7) | 6.8 ± 0.9 | −67.4 ± 0.7 (4) | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| A780P | −45.0 ± 0.7 (5) | 5.9 ± 0.8 | −39.4 ± 1.2 (4) | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 0.34 ± 0.07 |

| A780T | −44.0 ± 0.6 (5) | 5.1 ± 0.6 | −59.8 ± 0.9 (4) | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 0.24 ± 0.04 |

| A780V | −34.6 ± 0.8 (8) | 6.6 ± 0.7 | −54.3 ± 0.8 (4) | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 0.10 ± 0.05 |

| A780W | −49.3 ± 0.6 (7) | 5.9 ± 0.5 | −68.0 ± 0.8 (4) | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| IIIS6 G1193b | |||||

| G1193A | −12.1 ± 1.0 (6) | 5.7 ± 0.7 | −25.2 ± 1.1 (6) | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 0.27 ± 0.07 |

| G1193M | −33.6 ± 0.7 (8) | 6.4 ± 0.6 | −52.8 ± 1.0 (4) | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 0.34 ± 0.08 |

| G1193N | −46.5 ± 1.0 (5) | 5.6 ± 0.8 | −61.3 ± 0.9 (4) | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 0.38 ± 0.08 |

| G1193P | −37.7 ± 0.7 (7) | 6.3 ± 0.6 | −64.6 ± 1.0 (4) | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 0.18 ± 0.07 |

| G1193Q | −39.2 ± 0.8 (5) | 7.0 ± 0.7 | −64.4 ± 1.2 (4) | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 0.29 ± 0.08 |

| G1193T | −49.8 ± 1.0 (7) | 5.1 ± 0.6 | −70.0 ± 1.1 (5) | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 0.16 ± 0.07 |

| G1193V | −38.1 ± 0.7 (8) | 5.6 ± 0.6 | −60.4 ± 0.8 (5) | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 0.14 ± 0.08 |

| IVS6 A1503 | |||||

| A1503G | −41.4 ± 0.8 (5) | 5.8 ± 0.5 | −54.0 ± 1.0 (4) | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 0.31 ± 0.07 |

| A1503M | −29.2 ± 0.7 (8) | 5.9 ± 0.7 | −60.1 ± 1.0 (4) | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 0.26 ± 0.08 |

| A1503N | −31.5 ± 0.7 (5) | 6.3 ± 0.6 | −45.1 ± 1.1 (4) | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 0.32 ± 0.09 |

| A1503T | −17.9 ± 0.8 (7) | 8.7 ± 0.8 | −38.0 ± 1.2 (4) | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 0.29 ± 0.09 |

| A1503V | −11.4 ± 0.8 (5) | 7.2 ± 0.6 | −37.2 ± 1.2 (4) | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 0.24 ± 0.06 |

| A1503W | −16.9 ± 0.6 (9) | 6.6 ± 0.6 | −38.9 ± 1.3 (4) | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 0.33 ± 0.09 |

| A1503P | no current | ||||

| Double mutation | |||||

| G432S/S435G | −19.8 ± 0.9 (5) | 6.3 ± 0.7 | −39.2 ± 1.2 (4) | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 0.54 ± 0.07 |

a V0.5,inact lack of inactivation prevented quantitative estimations.

b V0.5,act data are from Beyl et al. (24).

FIGURE 3.

Inactivation changes induced by mutations of Gly-432 in segment IS6 of CaV1.2. A, averaged inactivation curves of wild-type (n = 5) and mutants G432A (n = 4) and G432N (n = 4). B, representative IBa through wild-type and indicated mutant channels during depolarizing test pulses from −100 mV to the peak potential of the I-V curve.

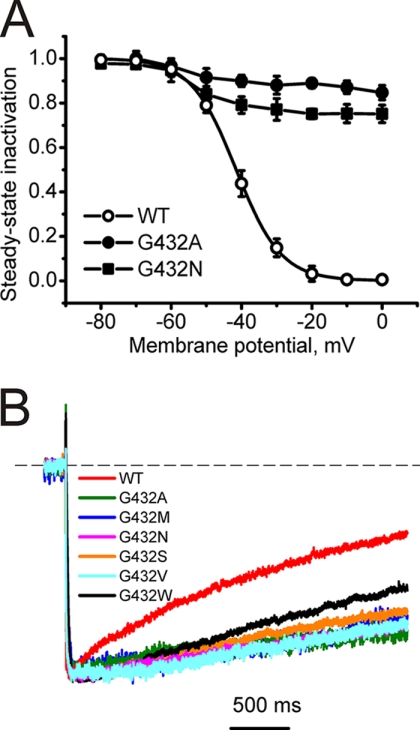

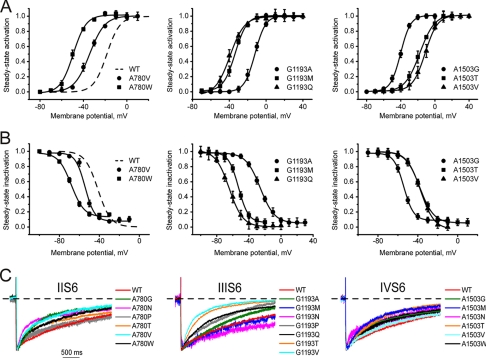

Mutations of Ala-780, Gly-1193, and Ala-1503 (Homologous to Gly-432) Affect Channel Activation but Preserve Inactivation

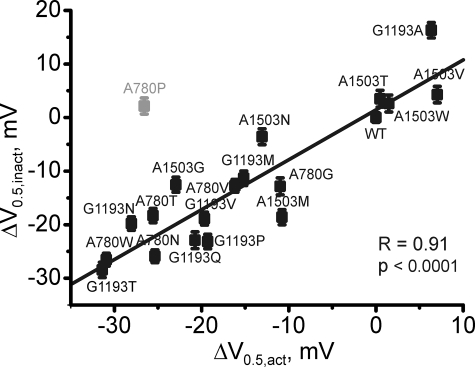

None of the mutations in positions Ala-780, Gly-1193, and Ala-1503 slowed channel inactivation, as observed with substitutions of Gly-432. The modulatory effects of mutations in these positions are illustrated in Fig. 4. We observed a strong correlation between the shifts of the activation and inactivation curves (Fig. 5, r = 0.91, p < 0.001) in domains II, III, and IV (see also Table 1), suggesting that the coupling between the two processes was intact. These data indicate a special role of Gly-432 in inactivation gating, in that only mutations of Gly-432 diminished inactivation, whereas substitutions in homologous positions in other segments either had no effect on inactivation or even made it faster.

FIGURE 4.

Mutations in the pore segments IIS6, IIIS6, and IVS6 in positions homologous to Gly-432 in IS6 induce significant shifts of activation and inactivation curves. A and B, shown is the averaged activation (A) and inactivation (B) curves of wild type and mutations of Ala-780 in segment IIS6 (left), Gly-1193 in segment IIIS6 (middle), and Ala-1503 in segment IVS6 (right). All mutations are summarized in Table 1. C, shown are representative IBa through wild type and the indicated mutant channels in segments IIS6-IVS6 during depolarizing test pulses from −100 mV to the peak potentials of the current-voltage relationships. No deceleration of inactivation was observed (compare with Gly-432 in IS6 in Fig. 3).

FIGURE 5.

Correlation between shifts of the midpoint of the inactivation and activation curves for G/A/G/A mutations in segments IIS6-IVS6. A proline mutation of Ala-780 (shaded) was excluded from correlation analysis as this residue is likely to disturb the link between voltage sensor and the channel pore (9, 24).

Structural Analysis of the G/A/G/A Motif

To visualize the location of G/A/G/A, homology models of CaV1.2 in open and closed conformation were analyzed. The open channel conformation has been published previously (30). A model of the closed CaV1.2 channel, including an insertion at the highly conserved asparagines, was developed by basing the structures of P-helices and selectivity filter segments on the NaChBac model (31), as both channels possess the same selectivity signature sequence. The S5 and S6 segments are based on the KcsA crystal structure. The alignment is shown in Fig. 1.

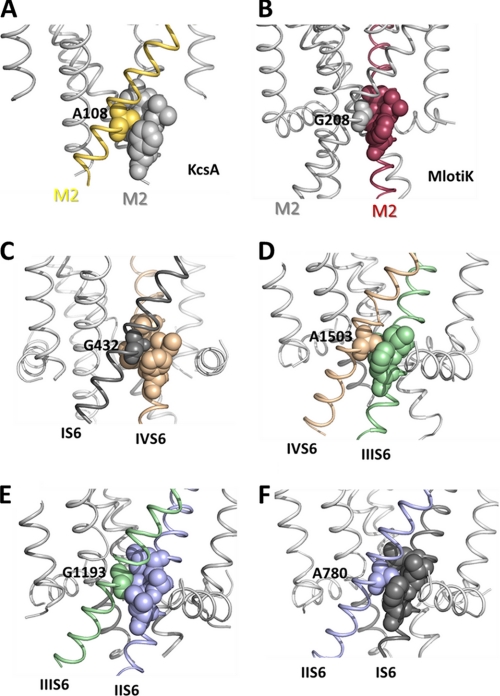

Residues in closed K+ channel crystal structures of KcsA and MlotiK that align with the G/A/G/A motif are positioned at the M2 helix-helix interface (Fig. 6, A and B). These helices correspond to S6 helices in calcium channels. The small amino acids in positions homologous to CaV G/A/G/A motif interact with bulky hydrophobic residues from the adjacent M2 helices. Interestingly, in both crystal structures the small Ala-108/Gly-208 are in close contact with a conserved phenylalanine (see alignment, Fig. 1) located two turns below in the neighboring pore helix. Our homology model of the closed conformation suggests similar interactions in CaV1.2 (Fig. 6, C–F). Small amino acids Gly-432, Ala-780, Gly-1193, and Ala-1503 are located at the S6-S6 interface, tightly surrounded by hydrophobic residues from the adjacent S6 segments. A structural hypothesis (Fig. 6, C–F) illustrates putative interactions of the G/A/G/A residues with adjacent bulky residues, e.g. phenylalanines in domains I, III, and IV and leucine in domain II. All residues that are located within a short distance (<7 Å of Cβ atom) of G/A/G/A according to our homology model are given in Table 2.

FIGURE 6.

Hypothetical role of small amino acids in helix-helix packing of voltage-gated ion channels. Shown are the location of an alanine (A) in the closed conformation crystal structures of KcsA and the location of a corresponding glycine (B) in Mlotik (34). C–F illustrate the location of the G/A/G/A residues interacting with bulky hydrophobic residues from the neighboring S6 segments (shown as spheres).

TABLE 2.

Potential interactions of G/A/G/A residues in the closed channel state (see the model in Fig. 6)

| Member of G/A/G/A | Neighboring residues (β−carbons <7 Å apart) |

|---|---|

| Gly-432 (IS6) | IS6: Asn-428, Leu-429, Leu-431, Val-433, Ser-435, Gly-436, IVS6: Val-1502, Ile-1505, Met-1506, Phe-1509 |

| Ala-780 (IIS6) | IS6: Leu-431, Gly-432, Leu-434, Ser-435, Gly-436, Phe-438 |

| IIS6: Asn-776, Val-776, Val-777, Leu-779, Ile-781, Val-783, Asp-784 | |

| Gly-1193 (IIIS6) | IIS6: Leu-779, Ala-782, Val-783, Leu-786 |

| IIIS6: Asn-1189, Ile-1190, Val-1192, Phe-1194, Val-1195, Ile-1196, Val-1197 | |

| IVS6: Asn-1499, Ala-1503 | |

| Ala-1503 (IVS6) | IIIS6: Gly-1193, Val-1195, Ile-1196, Phe-1199 |

| IVS5: Lys-1385 | |

| IVS6: Asn-1499, Leu-1500, Val-1502, Val-1504, Met-1506, Asp-1507 |

To further characterize this putative packing motif, the accessibility of the surrounding residues was calculated with the WHAT IF online server (19) (see Table 3). Calculations using KcsA and MlotiK crystal structures show that the amino acids corresponding to the G/A/G/A motif are inaccessible. Similar results are obtained when calculating the accessible molecular surface in our closed CaV1.2 homology model. The conserved phenylalanines are also generally inaccessible, with the exception of Phe-114 from the KcsA crystal structure. This might be due to incompleteness of the crystal structure, which lacks the slide helices.

TABLE 3.

Accessibility of residues at the contact interface between S6 (M2) helices

The G/A/G/A motif is shown in bold; conserved phenylalanines are underlined.

| Channel | Accessibilities of Amino Acids in the Bundle-crossing Region (Å2) |

|---|---|

| KcsA (PDB code 1k4c) | Thr-107 (5.9); Ala-108 (0.17); Ala-109 (14.19); Leu-110 (10.1). Ala-111 (2.44), Thr-112 (11.5), Trp-113 (56.8), Phe-114 (20.2) |

| MlotiK (PDB code 3beh) | Ala-207 (1.7); Gly-208 (0); Ile-209 (0.1); Leu-210 (1.2), Ala-211 (4.1), Thr-212 (2.4); Gly-213 (0); Phe-114 (1.9) |

| CaV1.2 I | Leu-431 (0); Gly-432 (0); Val-433 (0.6); Leu-434 (1.2); Ser-435 (0), Gly-436 (0); Glu-437 (17.1); Phe-438 (1.5) |

| CaV1.2 II | Leu-779 (0.3); Ala-780 (0); Ile-781 (7.3); Ala-782 (1.7); Val-783 (1.5); Asp-784 (1.5); Asn-785 (21.5); Leu-786 (2.9) |

| CaV1.2 III | Val-1192 (0.1); Gly-1193 (0); Phe-1194 (13.9); Val-1195 (6.9); Ile-1196 (0.1); Val-1197 (19.8); Thr-1198 (19.8); Phe-1199 (3.4) |

| CaV1.2 IV | Val-1502 (0); Ala-1503 (0); Val-1504 (5.5); Ile-1505 (9.7); Met-1506 (0.3); Asp-1507 (1.0); Asn-1508 (17.6); Phe-1509 (1.6) |

A comparison of closed and open crystal structure conformations of the bacterial potassium channel KcsA reveals large conformational changes upon gating, resulting in a displacement of this amino acid by more than 7 Å. Accessibility calculations show that this residue is accessible to water in the open channel conformation. Because several open and open-inactivated crystal structures are available, we calculated values for three different KcsA crystal structures (32) with the PDB identifiers 3f5w, 3fb7, and 3f7v. The obtained accessibility values (range 9.9–17.2 Å2) might reflect different degrees of channel opening. Similar accessibilities are obtained when calculating the accessible molecular surface in our open CaV1.2 homology model. The values are 14.4 Å2 (Gly-432), 11.8 Å2 (Ala-780), 11.1 Å2 (G1193), and 18.5 Å2 (A1503).

DISCUSSION

Reduced inactivation by TS mutations G406R and G402S results in sustained membrane depolarization and enhanced calcium entry through L-type channels into neuronal, myocardial, and other cell types (2). This slowing of channel inactivation is the key to understanding the wide spectrum of developmental abnormalities and pathological changes in different organs leading to cardiac arrhythmias, autism spectrum disorders, and other diseases (2). TS mutations affect the mechanism of calcium-dependent inactivation that occurs irrespective of expression of a fast (β1c-) or slow β2a-subunit (3, 4). Later studies revealed that mutation G436R (corresponding to the TS mutation G406R in humans) slows channel activation and deactivation, which may augment the arrhythmogenic effects of this mutation (33). Splawski et al. (2) emphasize that substitution of Gly-406 by different amino acids reduces inactivation similar to G406R. This finding was supported by data of Raybaud et al. (3) who substituted 11 different residues for the corresponding Gly-436 in the rabbit channel and found that all these mutations reduced voltage-dependent inactivation. However, the role of these residues in stabilization of the different conformational states of CaV1.2 remained elusive.

Splawski et al. (2) hypothesized, in analogy to potassium channels, that Gly-406 and Gly-402 may act as the hinge points during channel activation. Raybaud et al. (3) discussed a potential role of G402S and G406R in helix packing. In continuation of the work by Splawski et al. (2) and Raybaud et al. (3), we have substituted Gly-432 by residues of different physicochemical properties. Our homology model suggests that the Timothy Gly-432 is part of a motif of tightly packed small amino acids (Fig. 6, A–F). It was, therefore, interesting to compare gating changes induced by mutations in these positions of all four S6 segments.

Mutations of G/A/G/A Residues Affect Activation Gating

All mutations of the TS Gly-432 and homologous Ala-780, Gly-1193, and Ala-1503 affected the stability of the channel pore. The majority of mutations induced leftward shifts of the activation curves that were always accompanied by a slowing down of channel deactivation, suggesting a stabilization of the open and destabilization of the closed state (9, 24). Four mutations, G432A, G432V, G1193A, and A1503V, induced rightward shifts of the steady-state curve and exhibited corresponding fast activation and deactivation (Figs. 2 and 4), indicating a stabilization of the closed channel state.

To test the structural hypothesis that size is an important determinant of pore stability (supplemental Fig. S2) in the G/A/G/A positions, we applied mutation-correlation analysis (24). In all four positions the insertion of larger residues disturbed pore stability, as evident from shifts of the activation curve. In line with these data, characteristics of amino acid size (either molecular weight or Van der Waals volume) correlated in combination with hydrophobicity or flexibility indices with the shifts of the activation curve (supplemental Fig. S2). Despite their common impact on activation gating (all residues of G/A/G/A contribute to closed state stability), these residues interact in a domain-specific manner with their surrounding residues. As illustrated in supplemental Fig. S2, descriptors characterizing the size of the substituting residues (either molecular weight in domains I-III or Van der Waals volume in domain IV) correlate with the shifts of the activation curves. Domain-specific (asymmetric) contributions are evident from different impacts of hydrophobicity indices (domains I-III) and side chain flexibility (domain IV). Interestingly, mutating a small and flexible Gly-432 to a small but more rigid alanine or valine in domain I stabilized the closed state by shifting the activation curve by 5–7 mV. In domain IV, replacing a rigid Ala-1503 by a flexible glycine destabilizes the closed state by shifting the activation curve by ≈−20 mV. The asymmetric impact of pore mutations (i.e. domain specific contributions of G/A/G/A substitutions) on CaV1.2 gating warrants further research.

Structural Model of the G/A/G/A Region

To illustrate the structural location of the TS Gly-432 and the G/A/G/A motif residues, we refer to crystal structures of potassium channels and designed a homology model. The model supports the idea that the small amino acids are in close contact with bulky hydrophobic residues from neighboring S6 segments, thereby providing domain-domain interfaces (Fig. 6). In other words, these homologous residues are likely to be involved in tight S6-S6 packing of the closed channel conformation. If we see these interactions as stabilizing the closed conformation, then the insertion of larger residues would be expected to disrupt the packing and destabilize the closed state, as illustrated in supplemental Fig. S3.

Exclusive Role of Gly-432 in Channel Inactivation

In this study we asked the question of how structural changes in Gly-432 and homologous residues Ala-780, Gly-1193, and Ala-1503 affect channel inactivation. Our data revealed a high degree of positional specificity for mutations in position Gly-432. All mutations of Gly-432 slowed down or prevented inactivation (Fig. 3, Table 1), whereas substitutions in domains II-IV did either not affect, or even accelerated inactivation (Fig. 4C). Parallel shifts of the activation and inactivation curves (Fig. 5) indicate that mutations in these three domains do not affect the coupling between activation and inactivation supporting a gating scheme (R)est→(O)pen→(I)nactivated.

However, mutations in position Gly-432 suppress inactivation regardless of the stability of the activation gates. Any mutation that either stabilizes (e.g. G432A/V) or destabilizes (G432S/M/N/W) the closed resting state prevents channel inactivation, supporting a gating scheme R → O ↛ I. This is evident from Figs. 2 and 3, illustrating the observed stabilization of the closed state (shifts of activation curve to the right) and destabilization of the closed state (different shifts of the curve to the left or to the right, see supplemental Fig. S2A). Thus, despite the similar impact of Gly-432 and other residues of the G/A/G/A ring in channel activation, only Gly-432 (IS6) is essential for inactivation in an “all or none” manner.

Conclusions and Outlook

Our structure-activity studies suggest that the TS Gly-432 in domain I of CaV1.2 forms part of a ring of small and tightly packed residues (G/A/G/A) interacting with adjacent bulky hydrophobic amino acids. The identification of the particular interaction partners of the G/A/G/A ring in adjacent segments remains a challenge for future experimental studies (see Table 3). These small residues in the lower third of the CaV1.2 S6 segments are homologous to a ring of small residues in MlotiK and KcsA crystal structures. Systematic mutational studies and correlation analysis of CaV revealed that hydrophobic interactions in this region stabilize the channel closed state. The small size is apparently required for tight-fitting interactions with neighboring bulky residues of CaV1.2. The apparent structural homologies between KcsA and MlotiK and CaV in the pore region provide a guideline for the alignment of S6 segments. Only mutations of the TS Gly-432 disrupted the link between activation and inactivation, whereas substitution of the other alanines or the IIIS6 glycine in most cases simultaneously shifted activation and inactivation. The mechanism behind the unique effect of Gly-432 mutations on inactivation remains to be elucidated.

Ca2+ channels are expressed as a single polypeptide assembling into four pseudo-subunits. Although the pseudo-4-fold symmetry might be maintained in S6 helices, it is not preserved in the intracellular domains, where sequence length and interaction partners vary.

It is tempting to speculate that flexibility in IS6 is required for proper transmission of β-subunit-mediated effects on inactivation. Only Gly-432 in segment IS6 is linked to the β interaction domain (BID) located on I-II linker (35, 36). Mutations in position Gly-432 disrupt inactivation irrespective whether the CaV1.2 comprises a “fast-inactivating” β1 or a “slow-inactivating” β2a subunit (exemplified in supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting that the mutated CaV1.2 α-subunits (G432X) interact with their β subunits. Similar findings were previously reported for the Timothy mutations G406R (4). We have therefore substituted a flexible glycine for a serine one turn below Gly-432. The introduction of helix flexibility next to the TS mutation G432S partially rescued channel inactivation (supplemental Fig. S5). Flexibility in the lower third of segment IS6 may thus be a molecular determinant of β-subunit-mediated inactivation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Waheed Shabbir for technical assistance.

The work was supported by Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (Austrian Science Fund) Grants P22600 (to S. B.), W1232 (to S. H.), and P19614 (to S. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- TS

- Timothy syndrome.

REFERENCES

- 1. Splawski I., Timothy K. W., Sharpe L. M., Decher N., Kumar P., Bloise R., Napolitano C., Schwartz P. J., Joseph R. M., Condouris K., Tager-Flusberg H., Priori S. G., Sanguinetti M. C., Keating M. T. (2004) Cell 119, 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Splawski I., Timothy K. W., Decher N., Kumar P., Sachse F. B., Beggs A. H., Sanguinetti M. C., Keating M. T. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8086–8096; discussion 8086–8088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raybaud A., Dodier Y., Bissonnette P., Simoes M., Bichet D. G., Sauvé R., Parent L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39424–39436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrett C. F., Tsien R. W. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2157–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi C., Soldatov N. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6813–6821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hering S., Berjukow S., Sokolov S., Marksteiner R., Weiss R. G., Kraus R., Timin E. N. (2000) J. Physiol. 528, 237–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stotz S. C., Zamponi G. W. (2001) Trends Neurosci. 24, 176–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kudrnac M., Beyl S., Hohaus A., Stary A., Peterbauer T., Timin E., Hering S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12276–12284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hohaus A., Beyl S., Kudrnac M., Berjukow S., Timin E. N., Marksteiner R., Maw M. A., Hering S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38471–38477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardman R. M., Stansfeld P. J., Dalibalta S., Sutcliffe M. J., Mitcheson J. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31972–31981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Irizarry S. N., Kutluay E., Drews G., Hart S. J., Heginbotham L. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 13653–13662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paynter J. J., Sarkies P., Andres-Enguix I., Tucker S. J. (2008) Channels 2, 413–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Catterall W. A., Perez-Reyes E., Snutch T. P., Striessnig J. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 411–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harmar A. J., Hills R. A., Rosser E. M., Jones M., Buneman O. P., Dunbar D. R., Greenhill S. D., Hale V. A., Sharman J. L., Bonner T. I., Catterall W. A., Davenport A. P., Delagrange P., Dollery C. T., Foord S. M., Gutman G. A., Laudet V., Neubig R. R., Ohlstein E. H., Olsen R. W., Peters J., Pin J. P., Ruffolo R. R., Searls D. B., Wright M. W., Spedding M. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D680–D685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chenna R., Sugawara H., Koike T., Lopez R., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G., Thompson J. D. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicholas K. B., Nicholas H. B., Jr., Deerfield D. W., II (1997) EMBNEW NEWS 4, 14 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M. A., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M. Y., Pieper U., Sali A. (2007) Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci., Chapter 2, Unit 2.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vriend G. (1990) J. Mol. Graph 8, 52–56, 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grabner M., Dirksen R. T., Beam K. G. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1903–1908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perez-Reyes E., Castellano A., Kim H. S., Bertrand P., Baggstrom E., Lacerda A. E., Wei X. Y., Birnbaumer L. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1792–1797 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellis S. B., Williams M. E., Ways N. R., Brenner R., Sharp A. H., Leung A. T., Campbell K. P., McKenna E., Koch W. J., Hui A. (1988) Science 241, 1661–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamill O. P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F. J. (1981) Pflugers Arch. 391, 85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beyl S., Depil K., Hohaus A., Stary-Weinzinger A., Timin E., Shabbir W., Kudrnac M., Hering S. (2011) Pflugers Arch. 461, 53–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huber I., Wappl E., Herzog A., Mitterdorfer J., Glossmann H., Langer T., Striessnig J. (2000) Biochem. J. 347, 829–836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stary A., Kudrnac M., Beyl S., Hohaus A., Timin E. N., Wolschann P., Guy H. R., Hering S. (2008) Channels 2, 216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruhova I., Zhorov B. S. (2010) J. Gen. Physiol. 135, 261–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2998–3006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lipkind G. M., Fozzard H. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 6786–6794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stary A., Shafrir Y., Hering S., Wolschann P., Guy H. R. (2008) Channels 2, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shafrir Y., Durell S. R., Guy H. R. (2008) Biophys. J. 95, 3650–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cuello L. G., Jogini V., Cortes D. M., Pan A. C., Gagnon D. G., Dalmas O., Cordero-Morales J. F., Chakrapani S., Roux B., Perozo E. (2010) Nature 466, 272–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yarotskyy V., Gao G., Peterson B. Z., Elmslie K. S. (2009) J. Physiol. 587, 551–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clayton G. M., Altieri S., Heginbotham L., Unger V. M., Morais-Cabral J. H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1511–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Petegem F., Clark K. A., Chatelain F. C., Minor D. L., Jr. (2004) Nature 429, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vitko I., Shcheglovitov A., Baumgart J. P., Arias-Olguín I. I., Murbartián J., Arias J. M., Perez-Reyes E. (2008) PLoS One 3, e3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.