Abstract

Calcium carbonate exists in two main forms, calcite and aragonite, in the skeletons of marine organisms. The primary mineralogy of marine carbonates has changed over the history of the earth depending on the magnesium/calcium ratio in seawater during the periods of the so-called “calcite and aragonite seas.” Organisms that prefer certain mineralogy appear to flourish when their preferred mineralogy is favored by seawater chemistry. However, this rule is not without exceptions. For example, some octocorals produce calcite despite living in an aragonite sea. Here, we address the unresolved question of how organisms such as soft corals are able to form calcitic skeletal elements in an aragonite sea. We show that an extracellular protein called ECMP-67 isolated from soft coral sclerites induces calcite formation in vitro even when the composition of the calcifying solution favors aragonite precipitation. Structural details of both the surface and the interior of single crystals generated upon interaction with ECMP-67 were analyzed with an apertureless-type near-field IR microscope with high spatial resolution. The results show that this protein is the main determining factor for driving the production of calcite instead of aragonite in the biocalcification process and that –OH, secondary structures (e.g. α-helices and amides), and other necessary chemical groups are distributed over the center of the calcite crystals. Using an atomic force microscope, we also explored how this extracellular protein significantly affects the molecular-scale kinetics of crystal formation. We anticipate that a more thorough investigation of the proteinaceous skeleton content of different calcite-producing marine organisms will reveal similar components that determine the mineralogy of the organisms. These findings have significant implications for future models of the crystal structure of calcite in nature.

Keywords: Calcification, Calcium-binding Proteins, Chemical Biology, Protein Synthesis, Spectroscopy, Biomineralization, Calcite, Calcium Carbonate, Sclerites, Soft Corals

Introduction

The primary mineralogy of marine carbonates has changed over geological history depending on the magnesium/calcium ratio in seawater, including during the so-called “aragonite sea” (1) period and two periods of “calcite seas” (2). This ratio is apparently driven by changes in spreading rates along mid-ocean ridges (1). The calcification process of aragonite and calcite mineralogy in mollusk shells (3–8) and some information about calcite (9, 10) have been reported, but our knowledge of the mechanism of the direct biological formation of calcite in marine organisms, especially in corals, remains incomplete. To develop a more complete understanding of calcite formation, detailed information concerning how biomolecules contribute to the kinetics of crystal formation, as well as the structural details of both the surface and the interior of single crystals in the submicrometer to nanometer scale must be analyzed. The mechanism of calcite formation in soft coral sclerites that we report here is completely different from the mechanisms used by other calcifying marine organisms, featuring new chemical groups and different types of single crystals in the biomineralization process.

By investigating the novel functions of extracellular proteins, we have gained new insight into biomineralization strategies in the soft coral endoskeleton. Calcite and aragonite are two polymorphs of CaCO3 that are commonly observed in biominerals. They differ from one other in lattice structure and stability. Stony corals form needle-like aragonite crystals, whereas soft corals form only calcite crystals. An important unresolved question is how soft corals, unlike stony corals, form calcite without forming aragonite. To understand these in vivo mineralization processes, both the extraction fluid and the ionic composition should be considered. It is well known that sea water contains a high concentration of Mg2+ relative to Ca2+ (5:1 ratio). In solution, Mg2+ poisons calcite formation, whereas having only a minimal effect on aragonite precipitation (11). During crystallization in vivo, Mg2+ inhibits calcite formation, resulting in a predominance of aragonite crystals. For this reason, stony coral skeletons exclusively form aragonite crystals during calcification. A special case is that of soft corals, which form only calcite crystals. In this study, we explore the interesting, as yet uncharacterized phenomenon of how calcite crystals form in soft corals. We hypothesized that some biological processes, especially those involving matrix proteins (12, 13) and catalyzed by certain pivotal enzymes (e.g. carbonic anhydrase (14)), strongly influence and override the formation of calcite crystals. To gain an understanding of the details of this interesting phenomenon, we have characterized the proteins from a high abundance octocorallian soft coral, Lobophytum crassum, and we found that a reactive extracellular matrix protein (ECMP)3 is mainly responsible for calcite formation in the biocalcification process of soft coral despite the aragonite sea environment. However, the origin of ECMPs in soft corals is unknown. To address this question, we isolated proteins from the calcified endoskeletons (sclerites) of L. crassum (supplemental Fig. S1). Soft corals contain small spicules of calcium carbonate called sclerites, which are biomineralized structures composed of an organic matrix and a mineral (calcite) fraction. Calcite crystals, as shown in this study, are secreted on an organic matrix and then are transported to the outside of the cell for subsequent extracellular calcification in a process similar to sclerite calcification in the gorgonians (15, 16). Mature sclerites are completely free of cellular materials and ultimately become extracellular structures.

Detailed information regarding the function of ECMPs in the kinetics of crystal formation in endoskeletal sclerites has not been reported. One reason is that the purification of proteins from the organic matrix of soft coral sclerites is difficult due to the possibility of contamination by soft tissues and the high sensitivity of these matrices to handling. Key parameters of nucleating biomineralized chemical structures, which are formed by ECMPs, are still uncharacterized due to a lack of effective tools. Vibrational IR spectroscopy is a well established tool in materials and life sciences research; however, obtaining complete chemical information for protein-formed crystals by vibrational spectroscopy at IR wavelengths has been problematic because the diffraction limits of conventional IR microscopy result in low spatial resolution. The spatial resolutions of IR and Raman spectroscopy are ∼10 μm (17) and 1 μm, respectively. Therefore, submicrometer-to-nanometer-scale chemical structures are difficult to analyze by conventional IR spectroscopy. Specifically, scientists have been hampered by the difficulty of separating protein-complexed small molecules from biomineralized organisms. We have resolved this limitation by applying a newly developed near-field optical technique that permits IR spectral mapping below the optical diffraction limit with a spatial resolution of several hundred nanometers (17), a resolution that cannot be achieved by conventional IR spectroscopy. The principles of near-field IR (NFIR) microspectroscopy and a comparison between conventional Fourier transform IR spectroscopy and NFIR microspectroscopy have been recently reported (18), and this study showed that NFIR microspectroscopy is a useful technique for obtaining submicroscale-to-nanoscale chemical information. However, the present study is the first that utilizes NFIR microspectroscopy to analyze mineral-based CaCO3 crystals. NFIR microspectroscopy is a powerful tool for functional group analysis of nanoscale sample surfaces. This non-destructive method allows us to measure the distribution of organic polar functional groups, including hydrogen-bearing groups, together with those of hydrous minerals. In this study, the protein structures and chemical information in nucleated particles were also assessed using this approach.

We also introduce a new strategy for understanding the surface structure and related parameters of the protein-complexed single crystal kinetics involved in the calcification system. We employ techniques including atomic force microscopy (AFM), Raman spectroscopy, x-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and an electron probe microanalyzer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Isolation of Endoskeletons

Calcified endoskeletons (sclerites) were isolated from coral colonies using a series of mechanical and chemical treatments. The coral colony was cut into small pieces using sharp scissors. The pieces were ground 5–6 times in a mixer machine (BM-FE08, Zojirushi) and washed with tap water until the sclerites were obtained. The collected sclerites were cleaned and then stirred with 1 m NaOH for 2 h, at which point the sclerites were confirmed to be completely tissue-free. To ensure that the sclerites were tissue-free, they were stirred vigorously in a 10% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) bleaching solution for 1 h to remove fleshy tissues and debris. The treated samples were washed under tap water until the sclerites were completely cleaned. Finally, the samples were washed with Milli-Q water five times to remove contaminants. The sclerites were examined using a microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE E 200) to determine whether they were completely free of tissues and other contaminants. All steps in the isolation of sclerites from the colony were conducted at room temperature, and the materials obtained were stored at 4 °C until further use.

Purification of ECMPs

To extract proteins, bleached endoskeletons (∼10 g) were decalcified in 0.5 m EDTA-4Na (pH 7.8) overnight. The decalcifying solution was centrifuged (H-103 Kokusan) at 4000 rpm for 15 min to remove any insoluble materials, and the supernatant was filtered through filter paper (Advantec). To remove EDTA, the solution was then dialyzed at room temperature against 2 liters of ultrapure water (Milli-Q) for 72 h with 10 water changes using a dialysis membrane (UC36-32-100, Viskase Companies, Inc.). After dialysis, the solution was confirmed to be completely EDTA-free through an inhibitory effect study with or without EDTA and H2O. The protein concentration in the solution was measured by the Lowry method (19) using chicken ovalbumin (Kanto Chemical) as the standard protein followed by a spectrophotometric assay of protein concentration.

To avoid contamination by soft tissues, protein purification from the coral colony must be performed carefully. The steps for protein purification and protein sequencing are described below.

For step 1, the filtered samples were passed through two tandemly connected Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Waters) containing a silica-based bonded phase with strong hydrophobicity that typically adsorbs weakly hydrophobic components from aqueous solutions. The samples were passed through an aerator pump (Bio-Rad) to separate the soluble macromolecules. The Sep-Pak C18 cartridges were activated by methanol (3 × 4 ml) prior to passage of the samples. After the samples had been passed through the cartridges, we passed distilled water (5 × 6 ml) through each cartridge to completely remove the EDTA followed by 10% acetonitrile (3 × 2 ml). Finally, the adsorbed macromolecules were eluted in 50% acetonitrile (3 × 2 ml). The eluted macromolecules were frozen in a deep freezer (−80 °C) and subsequently lyophilized.

For step 2, the lyophilized sample was weighed (4 mg), mixed with 0.4 ml of 99% chloroform (CHCl3), 0.2 ml of 100% methanol (CH3OH), and 0.4 ml of H2O, and then centrifuged (Millipore) three times for 6 min each to remove lipids and other unwanted substances. Three layers were produced with each centrifugation, and only the upper layer (pure sample solution) containing H2O and CH3OH was collected. For the second and third centrifugation, H2O and CH3OH were added at the same concentration (CHCl3 was not added), and the upper layers were collected according to the same procedure as above. The sample was then concentrated by centrifugation in an Amicon Ultrafree-MC filter unit (Millipore) using a MiniSpin Plus microcentrifuge (Eppendorf) and dried using a centrifugal concentrator (VC-36N, TAITEC) under vacuum at 60 °C. After this step, the sample was ready for gel electrophoresis.

For step 3, the matrix proteins were separated on a gel. In this step, the dried sample was dissolved in 50 μl of sample buffer (6.25 m Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 50% glycerol, 10% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% bromphenol blue) and heated at 100 °C for 3 min. The samples were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (20) for ∼2 h.

For step 4, an electroeluter (Model 422, Bio-Rad) was used to purify the sample from the bands of interest. The visualized bands were excised from the gel using a sharp disposable blade. The bands that were excised from the gel were placed in the sample holders of the electroeluter. A separate holder was used for each protein. Electroelution was then conducted until elution was complete, which required ∼1.5–2 h. The protein concentration in each fraction, including ECMP-67, was measured by the Lowry method (19). The purified protein samples were then concentrated by centrifugation in Amicon Ultrafree-MC filter units (Millipore) using a MiniSpin Plus microcentrifuge (Eppendorf) and subsequently dried by centrifugation under vacuum.

For step 5, each purified protein was then redissolved in 25 μl of sample buffer. Finally, the purified samples were subjected to Tricine-SDS-PAGE using the same technique as described in step 3. In this final step, four purified proteins were observed on the SDS-PAGE gel. One strong band, ECMP-67, was highly prominent (supplemental Fig. S2, lane 3) and was partially sequenced after Western blotting using the Edman degradation technique.

Detection of Ca2+-binding and Glycosylated Proteins

After electrophoresis, the gel was placed on a PVDF membrane to transfer the proteins. Autoradiographs and labeling of the membrane with 45Ca were performed according to the method of Maruyama et al. (21). Autoradiographs of the 45Ca-labeled proteins on the PVDF membrane were obtained by exposure of the dried membrane to Kodak XAR-5 x-ray film for 1 week.

Periodic acid-Schiff staining was used for identification of the glycoproteins. This staining was performed using Schiff (fuchsin sulfite) reagent according to the method of Segrest and Jackson (22). A strong red/purple staining specified the glycoproteins.

Carbonic Anhydrase Assay

To examine carbonic anhydrase activity, each purified protein obtained by the procedure described above was subjected to carbonic anhydrase activity measurement using the CO2-Veronal indicator method (23) as follows. Six drops of phenol red (200 μl), 3 ml of 20 mm Veronal buffer (sodium 5,5-diethylbarbiturate, pH 8.3), and 0.5 ml of sample were mixed and placed in ice water. The reaction was started by adding 2 ml of ice-cold water saturated with CO2, and the time required for the color to change from red to yellow, indicating a pH drop to 7.3, was observed. The enzyme units (EU) were calculated according to the following equation

where T and To are the reaction times required for the pH to change from 8.3 to 7.3 at 0 °C with and without a catalyst, respectively.

Preparation of the Solution for in Vitro Crystallization

To investigate the effect of ECMP-67 on CaCO3 crystal formation, in vitro crystallization experiments were conducted using a solution containing the same components typically present in seawater. Two crystallization solutions were prepared: one that induces calcite formation (calcitic crystallization solution) and one that induces aragonite formation (aragonitic crystallization solution). The calcitic solution consisted of a supersaturated solution of Ca(HCO3)2 that was prepared by purging a stirred aqueous suspension of CaCO3 with CO2. CaCO3 was dissolved into CO2-aerated water, and excess precipitates were removed by filtration using filter paper (Whatman, 0.22 μm). The aragonitic solution was obtained by adding 50 mm MgCl2 to the calcitic solution. Crystallization experiments were conducted with and without the addition of protein (extracted from the sclerites) to each solution. The solutions (500 ml) were stirred for 10 min in a beaker and allowed to sit for 21 days without further manipulation.

NFIR Microspectroscopy

A solution of 1.4 μg/ml protein and 50 mm Mg2+, which is the concentration of Mg2+ in sea water, was used for NFIR analysis. Precipitated single crystals were harvested from the solution after completion of the experiment, and each experimental sample was used for near-field probing analysis. An apertureless-type near-field microscope (NFIR-200, JASCO Corp.) was combined with a Fourier transform IR spectroscopy spectrometer to detect near-field signals in the subwavelength regions of the samples. A newly developed near-field focusing plate was used for this measurement. The operation of the NFIR microscope was performed as described previously (24). The distance separating the sample and the probe was regulated by the uncontacted physical force interaction between the sample and the probe, and this distance was maintained at ∼30 nm. The probe tip oscillated parallel to the sample surface, and when the sample-probe separation became less than 100 nm, the diameter of the rotation of the probe decreased. The rotation signal was optically detected using a 690-nm laser diode and a silicon photodetector and fed back to the sample stage to regulate the probe-sample separation. The position of the sample being probed was altered by moving an X-Y PZT stage to change the measurement position. At each measurement point, topographic information about the sample surface was determined from the separation regulation signal, and an IR spectrum was obtained. Both large and small single crystals obtained from the calcification system were subjected to NFIR analysis. Exactly 8 × 8- or 10 × 10-μm areas on the surface of the particles were selected for topographic measurement. Spectral accumulation was measured 200 times at each point. The area of each measurement point (X:Y) was 0.25 × 1 μm.

Characterization of CaCO3 Crystal Growth by SEM

We identified single crystals on the basis of unit cell symmetry and the shape of the observed morphologies. Different concentrations of protein were added to the aforementioned calcite and aragonite solutions, and the resulting crystals were analyzed by SEM to determine the role of the proteins in the biocalcification process of soft coral sclerites. After protein addition and subsequent mixing, SEM glass plates (13 m/m) were placed on the bottom of the sample beakers to collect precipitated crystals. After completion of the in vitro experiments, the glass plates were then collected and lightly rinsed with distilled water to avoid any contamination and to stop further reaction. All specimens were air-dried in a desiccator and coated with palladium-gold using an ion coater (E-1010, Hitachi). The morphologies and different shapes of the crystals were then observed by SEM. The morphology of crystals formed in the presence of protein (affected crystals) was compared with that of crystals grown without protein (control crystals). The samples were examined using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-3000N) operated at 15 kV.

Raman Microprobe Spectroscopy

The same samples examined by SEM were examined by Raman spectroscopy prior to the SEM observation. To determine the polymorphism of single crystals, each sample was scanned for 30 s in the range of 0–3600 cm−1 using a JASCO NRS3200 Raman imaging microscope. After focusing on a single crystal, a diode laser (532 nm) was used as the light source of the microscope. The Raman laser beam was then focused on the same crystal at the same location for two additional repetitions.

EDX Analysis

An SEM-combined energy dispersive x-ray (EDX) (EDX-Genesis 4000) was used for spot analyses of the elements comprising selected sclerites and single crystals.

XRD

Precipitated crystals were collected from the bottom of a beaker (grown under the same conditions as for the NFIR, AFM, SEM, Raman, and electron probe microanalyzer experiments). The crystals were air-dried in a desiccator, finely ground using a hand grinder, and examined under a Nikon ECLIPSE E 200 microscope. The polymorphism of the crystals was then determined by an XD-D1 x-ray diffractometer (Shimadzu) using 30-keV copper Kα radiation.

In Situ AFM

The samples for AFM were obtained according by the same method as the in vitro experiments described above. A typical seed crystal of ∼0.5 cm3 in size was placed onto a glass coverslip in a 500-ml beaker for each experiment. After completion of the in vitro experiments, the crystal seeds were collected and lightly rinsed with distilled water to avoid any contamination and to stop further reaction. All specimens were air-dried in desiccators. The topography of the surface was mapped using an AFM in phase imaging mode, a variant of tapping mode imaging in which the phase lag of the cantilever oscillation relative to the signal sent to the piezo driver of the cantilever is used as a basis for image generation. Phase images can be generated as a consequence of variations in material properties such as friction. AFM observations were conducted with an SPM-9500 AFM (Shimadzu) at room temperature.

RESULTS

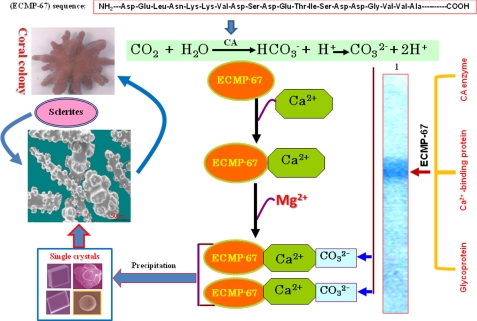

In this study, we analyzed several aspects of mineral-protein interaction to gain a more complete understanding of the process that determines whether calcite or aragonite is formed. We used several techniques to elucidate the structural details of both the surface and the interior of single calcitic crystals and to examine the interaction of the crystals with sclerite-derived proteins that are thought to be involved in the biocalcification process. We purified four ECMPs from sclerites with apparent molecular masses of 102, 67, 48, and 37 kDa. We named the four proteins ECMP-102, ECMP-67, ECMP-48, and ECMP-37, respectively, due to their molecular sizes (see supplemental Fig. S2) and putative extracellular origin (12, 13). Among the four proteins, ECMP-102 and ECMP-67 appeared to be calcium-binding proteins as they were detected as radioactive bands by 45Ca autoradiography (21) (supplemental Fig. S3). ECMP-102 and ECMP-67 also appeared to be glycosylated (supplemental Fig. S3, lane 3). Interestingly, both of these proteins showed carbonic anhydrase activity (see supplemental Table S1). Supplemental Table S1 shows that both ECMP-102 and ECMP-67 possessed specific carbonic anhydrase activity and that ECMP-67 showed higher activity than ECMP-102. To understand the biomineralization of sclerites, the four proteins were tested singularly, in pairs, and all together. We found complete crystallization in sclerites with the formation of different shapes and phases of single calcite crystals when we introduced either all of the proteins together or ECMP-67 alone. ECMP-67 was the most potent of the four proteins in forming calcite crystals in the biomineralization process. This protein has multiple strong functional properties, including being a Ca2+-binding glycoprotein with enzymatic activity and having an N-terminal amino acid sequence with 44 acidic residues out of the 175 determined (25). These characteristics are highly favorable for mineral formation in the sea. The primary N-terminal sequence of ECMP-67 was found to be NH2···Asp-Glu-Leu-Asn-Lys-Lys-Val-Asp-Ser-Asp-Glu-Thr-Ile-Ser-Asp-Asp-Gly-Val-Val-Ala···COOH.

We also analyzed amino acid composition with the extracellular matrix protein (ECMP-67) of sclerites. The composition of the matrix protein was characterized by a predominance of aspartic acid, comprising greater than 37% of all residues. Next in abundance was alanine, making up ∼14%, followed by glycine at about 11%, and then glutamate at about 8%. The total acidic residues (Asp + Glu = 45.44%) comprised almost half of the protein (supplemental Table S2).

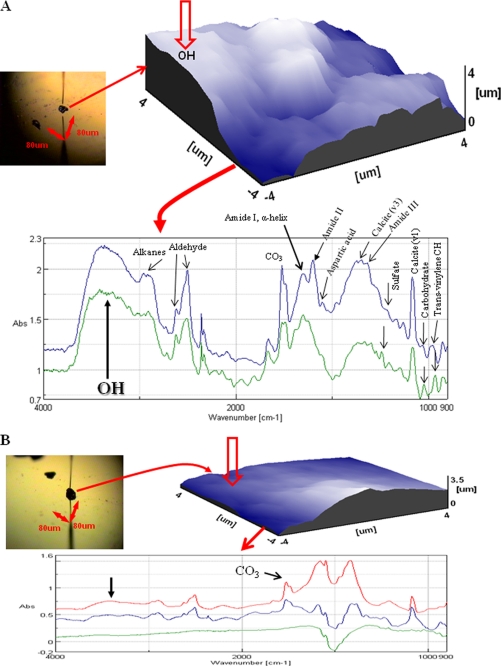

We identified single crystals on the basis of unit cell symmetry and the shape of the observed morphologies. Structural details of both the surface and the interior of single crystals on the submicrometer to nanometer scale were analyzed to gain a complete understanding of the morphology. In the first step, very small single crystals (∼25 μm) growing in a hard endoskeleton were investigated using an apertureless-type NFIR microscope with high spatial resolution. We investigated crystals (∼50% of which were single crystals) that were 25 μm in diameter (on average) to determine whether all had the same structural composition. NFIR spectra from a small single crystal particle, formed with and without the interaction of ECMP-67 in solution, are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1A, in the presence of ECMP-67 (1.4 μg/ml), a strong absorption peak is observed at 3400 cm−1, corresponding to the –OH group of a single crystal; however, this absorption is not observed for small crystals formed in the absence of proteins (Fig. 1B). Two strong bands representing calcite were detected at 1086.9 cm−1 (v1) and 1415 cm−1 (v3) in the presence of ECMP-67 (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the topographic NFIR image of single crystals grown with ECMP-67 clearly showed a rough surface with corresponding different heights for the bulk composition (Fig. 1A). In contrast, when ECMP-67 was absent, a planar surface was evident (Fig. 1B). The characteristic absorption bands of CO3 at 1800 cm−1 were observed in samples both with and without protein induction. However, in the absence of ECMP-67, only a weak signal is observed for the 1800 cm−1 band (Fig. 1B). The structures of the proteins and important chemical groups in the nucleating particles were also assessed. The NFIR spectra show the following important structural protein amide bands in a single crystal (Fig. 1A): amide I (1650–1700 cm−1), amide II (1550–1600 cm−1) and amide III (1300–1350 cm−1). A secondary structure, appearing to be an α-helix (generally associated with absorbance in the range from 1650 to 1658 cm−1 (26)) was observed at 1652 cm−1. The presence of a band arising from an amino acid side chain at 1574 cm−1 indicates an aspartic acid-rich protein based on the shape of amide II (27). Two absorption peaks to the right of the C–H stretch near 2850 and 2750 cm−1 that are caused by the C–H bond that is part of the CHO (aldehyde) functional group were also assigned to this particle. In addition, a band at 2900–2960 cm−1 corresponding to an alkane (–CH) was found. The weak absorption band at 1250–1260 cm−1 may be attributed to sulfate (28), which is most likely the O-sulfate group. The bands at 1050 and 970–990 cm−1 are indicative of a carbohydrate and a trans-vinylene CH (29), respectively (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

NFIR analyses of small single crystals obtained by the in vitro biocalcification process. A, an 8 × 8-μm topographic image of a protein-induced small single crystal and its complete bulk composition. The arrow on the topographic image indicates an –OH bond produced by the interaction with ECMP-67. The arrows on the NFIR absorption (Abs) spectrum indicate the complete bulk composition in the particle produced by ECMP-67 (see legend for supplemental Fig. 2 for details). Two positions on the crystal (blue and green spectra) were analyzed. B, depiction of the results of the near-field IR spectrum of a single particle that was taken from the calcitic solution. The experimental design was the same as shown in A, but the crystal was grown without ECMP-67. In the absence of the protein interaction, only CO3 bands were produced. This figure reveals that the calcifying organisms cannot produce an –OH bond (arrow on topographic image) and other necessary components for biocalcification without protein interactions. Three positions on the crystal were analyzed, as indicated by the red, blue, and green spectra.

The topographic images of relatively large single crystals (∼150 μm) and their NFIR spectra were investigated so that we might gain a structural understanding of nucleating large crystals and be able to compare this information with that obtained for small single crystals during the biocalcification process. The large single crystal produced in the presence of ECMP-67 (1.4 μg/ml) exhibits a relatively rough surface on which the height of the “mound” was measured to be ∼1.8 μm (see supplemental Fig. S4, A2). Typical CO3 bands in nucleated crystals obtained from an in vitro crystallization system in the presence of ECMP-67 (1.4 μg/ml) were investigated (see supplemental Fig. S4, A3). The topographic image is completely different in the absence of protein (see supplemental Fig. S4, B2). CO3 bands grow in supersaturated solutions in either the presence or the absence of protein; however, in the absence of protein, the bands are weaker (supplemental Fig. S4, B3). Therefore, the topographic view of the surface and the complete bulk composition of nucleating crystals obtained by the NFIR technique could be one of the most effective tools for analyzing the regulation of mineralization in calcified organisms.

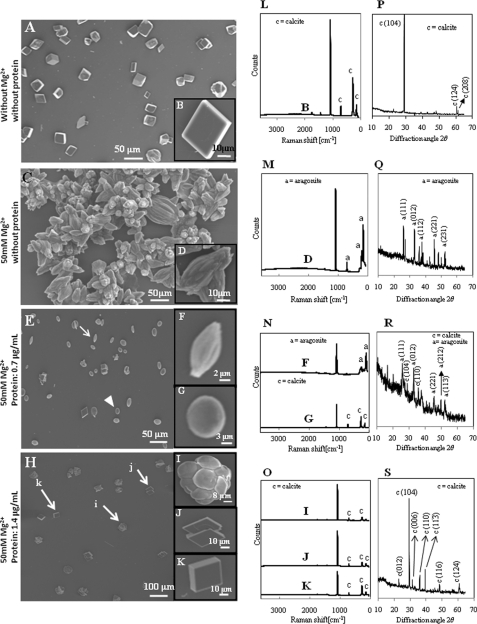

To further study the role of ECMP-67 in mineral formation, in vitro crystallization experiments were conducted with both calcitic and aragonitic solutions. First, the influence of Mg2+ on CaCO3 polymorphism was studied. In the absence of both Mg2+ and protein, typical rhombohedral calcite crystals were generated (Fig. 2, A, B, L, and P). In the presence of Mg2+ but without any protein, large needle-like aragonite crystals were formed (Fig. 2, C, D, M, and Q). When the solution was supplemented with ECMP-67, all of the crystals formed were calcite instead of aragonite (Fig. 2, H–K). Fig. 2, E–K, shows the SEM images of CaCO3 crystals grown in the presence of ECMP-67 at concentrations of 0.7 and 1.4 μg/ml. At a concentration of 0.7 μg/ml, a number of needle-like aragonite crystals remained (Fig. 2, E, arrow, and F), and some rhombohedral and round calcite crystals formed (Fig. 2E, arrowhead, and G). The Raman measurements (Fig. 2N) demonstrate that the former crystals (Fig. 2F) consisted of aragonite, and the latter consisted of calcite (Fig. 2G). Both crystallization mineral phases were confirmed by XRD (Fig. 2R). When ECMP-67 was present at a higher concentration (1.4 μg/ml), the calcite crystals (Fig. 2, H–K) formed different shapes, and no aragonite was observed. Although crystal growth was inhibited at high protein concentrations, all of the remaining aragonites formed by Mg2+ (50 mm) were transformed into calcites (Fig. 2H, enlarged view indicated by arrows in I, J, and K). Raman measurements showed that all single crystals formed under these conditions were calcites at 1086, 720, 288, and 162 cm−1 (Fig. 2O). At least 10 crystals with the same morphology were observed under an optical microscope, and their Raman spectra were individually measured. All crystals were of similar shape and polymorphism. The transition of minerals from aragonites to calcites was confirmed by XRD, which showed that all phases of the crystals were calcites and that no aragonites were present (Fig. 2S). These observations strongly suggest that ECMP-67 is the key component in calcite crystal formation during biocalcification and that an ECMP-67 concentration of 1.4 μg/ml is conducive to growing calcite crystals during the biocalcification process of soft corals. We also utilized commercial bovine serum albumin (BSA) and introduced it into the crystallization solution instead of ECMP-67 to confirm whether any other protein can affect crystal formation, but BSA failed to change the crystal formation from aragonite or calcite (see supplemental Fig. S5).

FIGURE 2.

SEM images of crystals grown in vitro and identification of their polymorphisms by XRD and Raman spectra. A and B, crystals grown without protein and in the absence of Mg2+ show a rhombohedral calcite morphology. C and D, crystals grown without protein and in the presence of Mg2+ appear as needle-like crystals (aragonite). E–G, crystals grown in the presence of protein (0.7 μg/ml) and Mg2+ (50 mm). H–K, crystals grown in the presence of protein (1.4 μg/ml) and Mg2+ (50 mm). L–O, verification of single crystals formed in these experiments by micro-Raman spectra. P–S, verification of the crystal polymorphisms formed in these experiments by XRD. The 2 θ scan diffraction angle identifies the calcite and aragonite minerals shown in SEM panels A, C, E, and H.

An EDX was used to analyze the chemical composition (i.e. calcium, magnesium, carbon, and oxygen content) of single crystals grown in the presence of ECMP-67. EDX showed that single calcite crystals contained low Mg2+ concentrations, although the solution contained a high concentration of Mg2+ (see supplemental Fig. S6 for details). The EDX analysis of nucleated crystals formed in the presence of ECMP-67 revealed novel functions of ECMP-67 in controlling the chemical composition of the crystals (see supplemental Fig. S6). The average elemental weight composition (atomic percentage) in a single crystal with 1.4 μg/ml protein (supplemental Fig. S6B, bottom) was found to be the following: calcium, 53.33; carbon, 15.75; oxygen, 29.26; and magnesium, 1.66. The protein-induced flower-shaped crystal exhibited a magnesium concentration of 1.66, indicating that this crystal is low magnesium calcite. In addition, the 2 θ diffraction angle scan identified this crystal as low magnesium calcite (Fig. 2S). The crystals formed in the control crystallization processes without protein or magnesium exhibited no magnesium signal. In contrast, the crystals formed in the control crystallization processes without protein but with magnesium showed a weak signal (0.58%), whereas crystal formation by protein induction showed a 3-fold stronger signal (1.66%), which is similar to the magnesium content of the sclerite (supplemental Fig. S6A, right-hand panel). These results indicate that ECMP-67 is highly influential in forming low magnesium calcite in the sea environment.

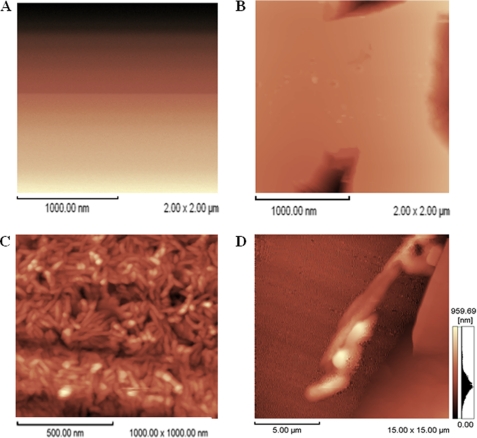

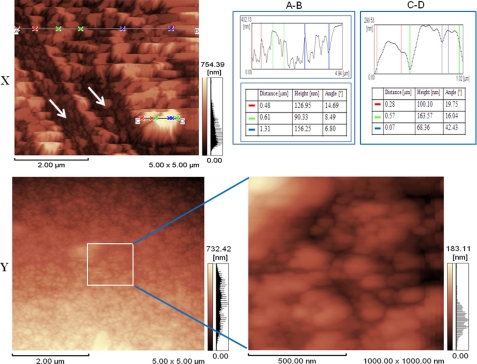

Finally, AFM was used to investigate whether the molecular-scale kinetics of crystal formation are indeed influenced by ECMP-67. Different sizes of rhombohedral (104) crystal seeds were used as substrates for in vitro crystallization experiments. The AFM image in Fig. 3A shows an example of a blank crystal that was used for this study. Crystallization was evaluated with or without the influence of Mg2+ ions. Because Mg2+ ions may influence production of aragonite crystals in the marine environment, we examined crystallization under the same environmental ionic conditions present in the sea and in the presence or absence of protein. As shown in Fig. 3B, crystal growth on the surface of the crystal was not observed by AFM in the absence of protein and Mg2+ ions. When we added 50 mm Mg2+, we observed that nanostructured aragonites were formed (Fig. 3C). Fig. 3D depicts a single aragonite crystal grown separately in 50 mm Mg2+. Although the substrate was a calcite, the AFM image clearly shows that the Mg2+ ions influence the experiment by causing the production of needle-like aragonite crystals.

FIGURE 3.

Atomic force microscopy topographic images of crystals grown in vitro without ECMP-67 on a calcite (104) substrate. A, AFM of a blank crystal surface. B, a single crystal in the absence of protein and Mg2+ ions. No growth was observed on the surface of the crystal under these conditions. C, a single crystal without protein, but with 50 mm Mg2+. Under these conditions, growth of needle-like aragonite crystals was observed on the surface, indicating the influence of Mg2+ on the growth of aragonite during calcification. D, topography of a single needle-like aragonite crystal grown with 50 mm Mg2+ and without protein. The AFM image clearly shows how the Mg2+ ions influence the crystallization process by producing needle-like aragonite crystals even with calcite (104) as the substrate.

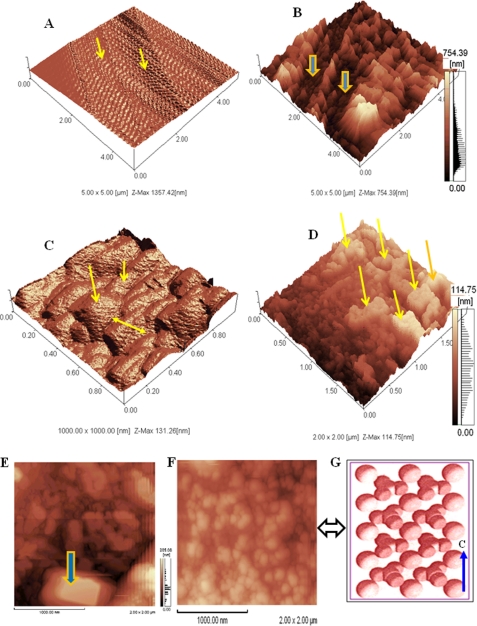

When 1.4 μg/ml protein was added to solutions under the same conditions as described for Fig. 3, B–D, and the crystals were collected during the initial stage of biocalcification after 7 of 21 total days, crystal growth processes were changed, and protein attachments to the surface (shown in white) were clearly visible (Fig. 4A). A total of five single crystals were checked at this initial stage of the crystal growth process, and all showed the same results. Again, we examined the crystal growth process using the same protein concentration (1.4 μg/ml) and experimental conditions, and crystals were collected during biocalcification after 14 of 21 total days. These crystals showed growth patterns that were different from the crystals in Fig. 3 (no protein present) and an earlier time point in Fig. 4A (Fig. 4B, arrows; see Fig. 5 for growth spacing details), indicating the potential influence of proteins during the biocalcification process (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Topographic AFM images of crystals grown in the presence of ECMP-67 and 50 mm Mg2+ ions in vitro for 21 days on calcite (104) substrates. A, topography of a single crystal grown with protein (1.4 μg/ml) and 50 mm Mg2+. The crystals were collected during the initial stage of biocalcification (7 of 21 total days). B, topography of a single crystal grown with the same protein concentration (1.4 μg/ml) and experimental conditions as those shown in Fig. 3, B–D, but after 14 days of biocalcification. This figure shows the initiation of calcite steps with larger edges (arrows), indicating the potential influence of proteins during the biocalcification process. C, a dynamic force plot of the surface of a single crystal with protein (0.7 μg/ml). The calcite formation step was initiated but not completed due to the low concentration of protein. D, a dynamic force plot of the surface of a single crystal with a standard concentration of protein (1.4 μg/ml). The calcite step edges were overgrown with protein attachments (arrows). E, a dynamic force plot of the substrate with 1.4 μg/ml protein. The step edges were smooth, and a rhombohedral calcite (104) crystal nanostructure (∼500 nm) was clearly visible on the surface (arrow). F, an AFM image of the surface structure in the presence of protein (1.4 μg/ml). A complete calcite structure was apparent and showed the same structural design as a rhombohedral calcite. G, a computer model of a rhombohedral calcite.

FIGURE 5.

Upper panel, X, molecular-scale AFM image of crystals formed in the presence of ECMP-67 (1. 4 μg/ml) after 14 of 21 total days of biocalcification showing initiation of calcite steps with larger edges (arrows). A and B, the molecular-scale full steps with spacing from starting point to end point. C and D, the molecular-scale specific points with spacing. The distance (μm), height (cm), and angle (°) of growth steps are clearly shown, as indicated by red, green, and yellow colors. Lower panel, Y, AFM image of the surface in the presence of proteins (1.4 μg/ml) showing a complete calcite structure. Left panel, the extended view of the crystal defined by the box reveals the same structural design as an ideal rhombohedral calcite.

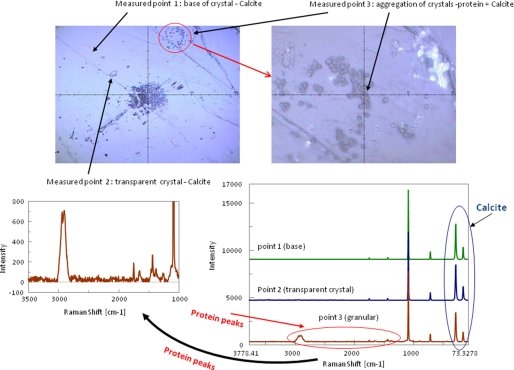

When a low concentration of protein (0.7 μg/ml) was added to solutions under the same conditions, as shown in Fig. 3, A and B, calcite growth was initiated (Fig. 4C, arrows) but was incomplete. In one experiment, when we added 1.4 μg/ml protein under the same conditions, the calcite crystals grown were clearly visible by protein attachment (Fig. 4D, arrows). The mineral and protein attachments on the same crystals were examined by a Raman microprobe (Fig. 6). The Raman microprobe clearly showed the protein attachments on the surface of single crystals (Fig. 6, protein peaks) and that the crystals produced by the influence of protein were completely calcite (see Fig. 6 for details). In Fig. 4D, the arrows on the topography plot depict crystal growth with fluffy white proteins on top. After completion of this 21-day experiment, the nanostructure (∼500 nm) of a rhombohedral calcite (104) crystal was clearly visible (Fig. 4E, arrow). An AFM image of the surface structure in the presence of 1.4 μg/ml protein shows a complete calcite shape (Figs. 4F and 5Y), and this shape was consistent with the original rhombohedral calcite structure shown in Fig. 4G (a computer model).

FIGURE 6.

Raman spectroscopy of protein attachment to crystals formed in the presence of ECMP-67 (1. 4 μg/ml) during the biocalcification process. The Raman spectra show that all crystals were calcite.

DISCUSSION

Biologically controlled calcification is almost always controlled by polysaccharides or proteins, which act as templates or so-called matrix proteins (12) or catalyze certain pivotal reactions (e.g. carbonic anhydrase (14)). Our results demonstrate that only a single reactive protein, ECMP-67, is necessary to regulate mineralogy in vitro. This protein provides crucial insight into how some marine animals might be able to control and maintain their preferred skeletal mineralogy even when the ocean chemistry changes to favor a different calcium carbonate variety. During the history of the earth, this chemistry change has likely occurred quite often, and evidence of these changes is seen in the preferred skeletal mineralogy adopted by different taxa according to the sea water chemistry at the time of their origin (30).

A high magnesium/calcium ratio in seawater strongly favors aragonite over calcite precipitation (1, 11). The means by which organisms can precisely control their skeletal mineralogy despite what would be favored by ocean chemistry, however, remained elusive. Using several different approaches, we established that the ECMP-67 protein extracted from soft coral sclerites controls the formation of calcite crystals in vitro even when aragonite is favored by the chemistry of the solution from which the crystals are precipitated. Furthermore, the –OH group (either carboxylic or alcoholic) and other structural features detected in the protein-containing calcite may play a key role in the process of forming low magnesium calcite in soft corals. As demonstrated above, the near-field IR spectrum of the small protein-induced calcite particle contains a stronger –OH bond than the larger particle. We thus assumed that although the adsorption of proteins onto the surface may inhibit the aging of the crystals, it strongly influences the formation of a crystal face; however, a weak protein-crystal surface interaction may not be a strong inhibitor and may permit the growth of a relatively large crystal. SEM analysis clearly showed that protein-induced crystals are much smaller than control (uninduced) crystals (Fig. 2, A–K). In this study, we established that the protein ECMP-67 in soft corals only influences the production of calcite crystals and, therefore, the –OH group obtained in proteinaceous calcite may be a key factor in its formation. The topographic image of the single crystal formed in the presence of ECMP-67 clearly depicts a rough surface with different heights for the bulk composition. In contrast, a topographic image of a single crystal in the absence of any proteins depicts a planar surface. Near-field IR analysis suggests that ECMP-67 in soft corals is potentially involved in the formation of the coral body structure through small chemical compounds via sclerites. This new technique enables the chemical structure of submicrometer-to-nanometer-scale samples to be optically analyzed. Our results constitute the first practical implementation of near-field IR spectroscopy for biomineralization applications.

Protein attachments on the surfaces of crystals (Fig. 4, A and D, white) were clearly visible, and these attachments functioned as templates for the growing calcite. Furthermore, protein attachment on the crystal surface during the biocalcification process was confirmed by a Raman microprobe (Fig. 6). Several experiments using different time scales in the biocalcification process were conducted in the presence of varying concentrations of protein to obtain a complete characterization of the transition from aragonite to calcite. A protein concentration of 1.4 μg/ml was found to be conducive for growing a calcite crystal (Figs. 4, B–G, 5, and 6).

The solution from which crystals were precipitated contained 50 mm Mg2+ and 10 mm Ca2+ (i.e. a 5:1 ratio), which would strongly favor precipitation of only aragonite (31, 32). However, two strong bands at 1086.9 cm−1 (v1) and 1415 cm−1 (v3) in the NFIR spectrum, corresponding to calcite, were detected (Fig. 1A) when the crystals were precipitated from a solution that contained 1.4 μg/ml ECMP-67 (Fig. 2). As predicted (11), aragonite was formed when ECMP-67 was absent from the solution (Fig. 2C), indicating that ECMP-67 can control the formation of the mineral phase.

In coral mineralization, transporters such as proton and Ca2+ pumps, components involved in morphology control, and enzymes involved in hydration of CO2 are all considered to play essential roles. Soluble anionic macromolecules, including glycoproteins and calcium-binding proteins, are known to function as inhibitors or stabilizers by binding precursor amorphous calcium carbonate, which acts as a template for the transition of amorphous calcium carbonate to structured crystals on an insoluble or soluble organic matrix (33). However, triple functionality is necessary for complete crystallization in corals, especially in the sclerites of soft corals. Isolated ECMP-67 possesses carbonic anhydrase and calcium binding activity, as well as glycosylation, all of which allow it to function in calcium carbonate crystal formation. In the soft coral sclerites, aragonite precipitation is the expected initial state because of the high concentration of magnesium ions (magnesium/calcium = 5:1) in the sea. The growing crystals are then excluded from the cell, and some biological processes, especially those involving extracellular proteins (here, ECMP-67), strongly influence and override the formation of calcite crystals. The multifunctionality of ECMP-67 indicates that it is not only a structural protein, but also a catalyst and a potential template for single crystal formation in soft coral sclerites. These results demonstrate that a single reactive protein is likely to function as a determinant of skeletal mineralogy in soft coral sclerites, thereby providing an essential clue to how these organisms can determine their skeletal mineralogy.

Based on our findings, we propose a model of how the calcified sclerites of soft coral are formed (Fig. 7). CO2 produced by respiration is converted to HCO3− by the carbonic anhydrase enzyme in the presence of H2O. After binding of calcium ions by Ca2+-binding proteins, ECMP-67 modulates the stereochemical position of carbonate groups dissociated from HCO3− to generate calcite crystals (Fig. 7). Because calcium carbonate is soluble at an acidic pH, the protons produced by the enzymatic reaction may be diluted in seawater or removed with a proton pump. In this scheme, ECMP-67 is a potential regulator of skeletal mineralogy in soft coral and greatly facilitates sclerite formation. However, further precise functional analyses of the effect of this protein on nucleation and growth of calcite crystals may lead to a deeper understanding of various biomineralization processes in many organisms.

FIGURE 7.

A model for sclerite formation by ECMP-67 in soft coral. Lane 1 shows the triple functional protein (ECMP-67) after purification by electroelution treatment. The primary sequence of ECMP-67 is shown at the top of the figure. CA enzyme, carbonic anhydrase enzyme.

The mechanisms underlying the formation of single crystals (calcites) that have been shown here, as well as the postulated mechanisms, may have direct biological relevance and broad implications in environmental sciences and in the synthesis of many types of materials, including catalysis, tissue engineering, biomaterials, and drug design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Chihiro Jin, JASCO Corp., for technical assistance in the near-field IR analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6 and Tables S1 and S2.

- ECMP

- extracellular matrix protein

- NFIR

- near-field infrared

- AFM

- atomic force microscopy

- XRD

- x-ray diffraction

- EDX

- energy dispersive x-ray

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stanley S. M., Hardie L. A. (1998) Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 144, 3–19 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sandberg P. A. (1983) Nature 305, 19–22 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falini G., Albeck S., Weiner S., Addadi L. (1996) Science 271, 67–69 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Addadi L., Joester D., Nudelman F., Weiner S. (2006) Chemistry 12, 980–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson J. B., Paloczi G. T., Kindt J. H., Michenfelder M., Smith B. L., Stucky G., Morse D. E., Hansma P. K. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 3307–3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Metzler R. A., Evans J. S., Killian C. E., Zhou D., Churchill T. H., Appathurai N. P., Coppersmith S. N., Gilbert P. U. P. A. (2010) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6329–6334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amos F. F., Destine E., Ponce C. B., Evans J. S. (2010) Crystallogr. Growth Des. 10, 4211–4216 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Belcher A. M., Wu X. H., Christensen R. J., Hansma P. K., Stucky G. D., Morse D. E. (1996) Nature 381, 56–58 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stephenson A. E., DeYoreo J. J., Wu L., Wu K. J., Hoyer J., Dove P. M. (2008) Science 322, 724–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D'Souza S. M., Alexander C., Carr S. W., Waller A. M., Whitcombe M. J., Vulfson E. N. (1999) Nature 398, 312–316 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis K. J., Dove P. M., De Yoreo J. J. (2000) Science 290, 1134–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weiner S., Hood L. (1975) Science 190, 987–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rahman M. A., Isa Y., Uehara T. (2005) Proteomics 5, 885–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jackson D. J., Macis L., Reitner J., Degnan B. M., Wörheide G. (2007) Science 316, 1893–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldberg W. M., Benayahu Y. (1987) B. Mar. Sci. 40, 287–303 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kingsley R. J., Watabe N. (1982) Cell Tissue Res. 223, 325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kebukawa Y., Nakashima S., Nakamura-Messenger K., Zolensky M. E. (2009) Chem. Lett. 38, 22–23 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koga S., Yakushiji T., Matsuda M., Yamamoto K., Sakai K. (2010) J. Membr. Sci. 355, 208–213 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maruyama K., Mikawa T., Ebashi S. (1984) J. Biochem. Tokyo 95, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Segrest J. P., Jackson R. L. (1972) Methods Enzymol. 28, 54–63 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang S. Y., Tsuzuki M., Miyachi S. (1985) Plant Cell Physiol. 26, 25–34 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Narita Y., Kimura S. (2001) Anal. Sci. 17, (suppl.) i685 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rahman M. A., Isa Y., Uehara T. (2006) Mar. Biotechnol 8, 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dauphin Y. (2006) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 145, 54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Venyaminov SYu., Kalnin N. N. (1990) Biopolymers 30, 1243–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prange A., Arzberger I., Engemann C., Modrow H., Schumann O., Trüper H. G., Steudel R., Dahl C., Hormes J. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1428, 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kupka T., Lin H. M., Stobinski L., Chen C. H., Liou W. J., Wrzalik R., Flisak Z. (2010) J. Raman. Spectrosc. 41, 651–658 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhuravlev A. Y., Wood R. A. (2008) Geology 36, 923–926 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivadeneyra M. A., Delgado R., Párraga J., Ramos-Cormenza A., Delgado G. (2006) Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 51, 445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weber J. N. (1974) Am. J. Sci. 274, 84–93 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cölfen H., Mann S. (2003) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 2350–2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.