Abstract

The mitochondrial import receptor Tom70 contains a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) clamp domain, which allows the receptor to interact with the molecular chaperones, Hsc70/Hsp70 and Hsp90. Preprotein recognition by Tom70, a critical step to initiate import, is dependent on these cytosolic chaperones. Preproteins are subsequently released from the receptor for translocation across the outer membrane, yet the mechanism of this step is unknown. Here, we report that Tom20 interacts with the TPR clamp domain of Tom70 via a conserved C-terminal DDVE motif. This interaction was observed by cross-linking endogenous proteins on the outer membrane of mitochondria from HeLa cells and in co-precipitation and NMR titrations with purified proteins. Upon mutation of the TPR clamp domain or deletion of the DDVE motif, the interaction was impaired. In co-precipitation experiments, the Tom20-Tom70 interaction was inhibited by C-terminal peptides from Tom20, as well as from Hsc70 and Hsp90. The Hsp90-Tom70 interaction was measured with surface plasmon resonance, and the same peptides inhibited the interaction. Thus, Tom20 competes with the chaperones for Tom70 binding. Interestingly, antibody blocking of Tom20 did not increase the efficiency of Tom70-dependent preprotein import; instead, it impaired the Tom70 import pathway in addition to the Tom20 pathway. The functional interaction between Tom20 and Tom70 may be required at a later step of the Tom70-mediated import, after chaperone docking. We suggest a novel model in which Tom20 binds Tom70 to facilitate preprotein release from the chaperones by competition.

Keywords: Biophysics, Chaperone Chaperonin, Heat Shock Protein, Mitochondria, Protein Complexes, Protein Targeting

Introduction

Recent proteomic studies suggest that there are as many as 1,000 mitochondrial proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1, 2) and 1,500 in mammals (3, 4). The majority of these mitochondrial proteins are encoded by the nuclear genome and translated by cytosolic ribosomes, except for a few that are encoded by the mitochondrial genomic DNA (5, 6). Many mitochondrial proteins are post-translationally imported into the mitochondria and then allocated to their destined subcompartments by various import and sorting machineries. The translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM)2 machinery serves as the general entry gateway into the mitochondria. It includes two preprotein import receptors, Tom20 and Tom70, and a general import pore (GIP) complex composed of the channel-forming protein Tom40, the organizing protein Tom22, and other small Tom proteins. Tom20 is the initial recognition site for preproteins synthesized with the classical N-terminal amphipathic presequence, many of which are destined for the matrix or intermembrane space. Preproteins with internal targeting sequences, such as inner membrane metabolite carriers, are recognized by Tom70 and imported in a chaperone-dependent manner. After the initial recognition on the outer mitochondrial membrane, preproteins are directed by the import receptor Tom20 or Tom70 to the GIP, through which they are translocated into the mitochondria (7).

Tom70 is a member of the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) co-chaperone family characterized by a specialized dicarboxylate TPR clamp domain that interacts with molecular chaperones, Hsp70/Hsc70 and/or Hsp90. Such an interaction between the TPR clamp and the molecular chaperones was first characterized in the cytosolic co-chaperone, Hop. The consensus EEVD motif at the C terminus of the chaperones was found to be absolutely necessary for the interaction with the TPR clamp. In addition, hydrophobic residues upstream of the EEVD motif contribute to the specificity of chaperone binding, as well as stabilization of the interaction (8, 9). Although Hop contains a TPR1 domain specific for Hsc70/Hsp70 binding and a TPR2A domain specific for Hsp90, Tom70 has a single TPR clamp domain in the N-terminal region that can bind either chaperone (10, 11). Therefore, the import receptor Tom70 serves as a docking site for cytosolic multichaperone complexes that contain preprotein and the co-chaperones DNAJA1 and DNAJA2 (10, 12). This chaperone-docking step is considered essential for the initiation of the Tom70-mediated import pathway where the preprotein is in direct contact with Tom70 (10, 13). The preprotein is then released from the receptor Tom70 in an ATP-dependent manner for translocation across the GIP, followed by integration into the inner membrane, which requires the membrane potential (7). In addition to importing many inner membrane carrier proteins, Tom70 is also implicated in targeting Mcl-1 to the outer membrane via an internal EELD sequence (14).

Although the chaperone-Tom70 interaction is well characterized, the mechanism by which Tom70 coordinates interactions with preproteins in the multichaperone complex remains unknown. It is also unclear how preproteins are released from Tom70 and delivered to the GIP. The GIP was characterized as a stable complex of ∼400 kDa by Blue Native PAGE and size exclusion chromatography and was thought to contain two or three dimers of Tom40, along with Tom22 and small Tom proteins (15–18). Tom22 has been shown to interact with Tom20 and Tom70, presenting a possible mechanism to recruit receptor-bound proteins to the GIP (18, 19). However, previous studies have provided evidence that Tom20 is stably associated with the GIP and plays a role in higher order structural assembly in the TOM complex. Under mild solubilization conditions with digitonin, Tom20 was loosely associated with the GIP, and they co-migrated above 400-kDa on Blue Native PAGE, but Tom70 remained separate (16, 20). A similar GIP complex containing Tom20 was also purified by affinity chromatography (20). Electron micrographs of the TOM complex isolated from wild-type yeast have shown three pores, whereas those from a yeast mutant lacking Tom20 showed only two pores (15, 17, 21, 22). Furthermore, when the membrane potential was disrupted, the import of Tom70-dependent ADP/ATP carrier was arrested in the GIP complex, and interestingly, the ADP/ATP carrier generated a cross-link with Tom20, as well as Tom70 (23). Therefore, it is possible that Tom20 could remain stably complexed with the GIP and that Tom70 is recruited to the GIP via a previously reported interaction with Tom20 (24), although this interaction could not always be observed in experiments with yeast (16, 18, 20). The human GIP appears conserved in these main features and mechanisms (25–27). Intriguingly, human Tom20 was found to interact with a cytosolic TPR co-chaperone AIP (28).

Here, we report a direct interaction between Tom20 and Tom70. Using cross-linking, co-precipitation, and NMR titrations, we determined that a DDVE motif at the C terminus of Tom20 is required to interact with the TPR clamp of Tom70, as well as an additional binding site in the central domain of Tom20 that enhances the binding affinity. Although Tom20 competes with the molecular chaperones for interaction with Tom70, antibody blocking of Tom20 adversely affected the import of both Tom20- and Tom70-dependent preproteins. This interaction may represent a mechanism to displace the molecular chaperones so that preproteins can be released for translocation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Unless stated otherwise, all of the chemical reagents were from Sigma or BioShop Canada Inc. (Mississauga, Canada). Restriction enzymes and other recombinant DNA reagents were from New England Biolabs, Invitrogen, and Stratagene. The QuikChange mutagenesis kit was from Stratagene, TnTTM-coupled reticulocyte lysate system was from Promega, and [35S]methionine/cysteine labeling mix was from GE Healthcare. The cross-linker sulfo-succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (s-SMCC) was from Pierce. [15N]Ammonium chloride and [13C]glucose were from Isotec. Peptides derived from human Tom20 (AQSLAEDDVE) and the control reverse sequence (EVDDEALSQA), as well as from Hsc70 (SSGPTIEEVD) and Hsp90α (DDTSRMEEVD) were synthesized by the Sheldon Biotechnology Center (Montreal, Canada).

Plasmids

Sequences encoding full-length human Tom70 were in pGEM-4Z and the cytosolic fragment (residues 111–608) in pProExHTa (10). The mutation R192A in the TPR clamp of human Tom70 was previously introduced by PCR (10). Sequences encoding full-length human Tom20 (residue 1–145) and its C-terminal deletion mutant (residue 1–141) were amplified by PCR from a plasmid template provided by G. C. Shore and inserted into pGEM-4Z. Sequences encoding the “core” to C-terminal domain of human Tom20 (residue 59–145), its C-terminal deletion mutant (residue 59–141), and its C-terminal region (residue 127–145) were similarly inserted into pGEX-6P1. Sequences encoding the C-terminal fragments of human Hsp90α (residue 566–732; C90) (10) and Bag1M (residue 151–263; CBag) (29) were in pProExHTa. The sequence encoding bovine phosphate carrier (PiC) (30), fungal ISP (from W. Neupert), and bovine ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) (from N. J. Hoogenraad) were in pGEM-3 and murine ANT2 in pGEM-4Z (11).

Protein Purification and Antibodies

The His-tagged cytosolic fragments of human Tom70 and clamp mutant (denoted His-WTΔN and His-R192AΔN) were purified as described (11). For NMR titrations, the His tag was removed by tobacco etch virus protease, and the cleaved Tom70ΔN was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer K (100 mm NaCl and 20 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5). The GST-fused cytosolic fragments of Tom20 were purified as described with modifications (31, 32). GST-tagged core to C-terminal fragment of human Tom20 and C-terminal deletion mutant (denoted GST-Tom20ΔN and GST-Tom20ΔNΔC) were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells and induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 22 °C for 16 h. The cells were lysed by sonication, and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The GST-tagged proteins were bound to a glutathione-Sepharose high performance column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in PBS and eluted with PBS and 20 mm glutathione. For NMR experiments, proteins were labeled by growing E. coli BL21(DE3) in M9 medium with [15N]ammonium chloride or [15N]ammonium chloride/[13C]glucose as the sole sources of nitrogen and carbon. For GST-Tom20ΔN and GST-Tom20ΔNΔC, the GST tag was removed by PreScission Protease in the presence of 20 mm CHAPSO, leaving a Gly-Pro-Leu-Gly-Ser extension at the N terminus, and further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer K. The GST-tagged C-terminal fragment of human Tom20 (GST-Tom20C) was expressed and purified by affinity chromatography as above. After PreScission Protease treatment and removal of GST, the remaining protein mixture was loaded onto a C18 column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA) equilibrated with 0.1% TFA and eluted in a linear gradient of acetonitrile from 0 to 50% in 50 min at 3 ml/min. Fractions containing Tom20C fragment were collected and lyophilized. For SPR, recombinant C90 and CBag were purified as described previously (10, 29). Specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against His-Tom70ΔN (13), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human Tom20 were provided by G. C. Shore. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against Tom22 were from AbCam.

Co-precipitation

In a typical co-precipitation, 5 μm of GST, GST-Tom20ΔN, and GST-Tom20ΔNΔC were incubated with 25 μm of His-WTΔN or His-R192AΔN in buffer K with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2 mg/ml ovalbumin and recovered by glutathione-Sepharose beads for 30 min at 4 °C. The beads were washed with buffer K with 0.1% Triton X-100 and eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. Where indicated, control peptide and peptides from Tom20, Hsc70, or Hsp90α were added at stated concentrations in excess of the GST fusion proteins (5 μm) for competition.

NMR Spectroscopy

All of the NMR experiments were performed at 301 K using a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer. Backbone assignments were performed with 13C,15N-labeled Tom20ΔN and Tom20C by standard heteronuclear techniques using backbone amide to Cα and Cβ correlation experiments. Titrations were carried out using 15N-labeled Tom20ΔN, Tom20ΔNΔC, and Tom20C titrated with unlabeled Tom70ΔN. Chemical shift changes were calculated according to the following formula.

|

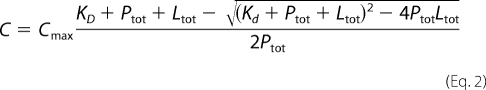

To determine KD, the chemical shifts changes were fit to the following equation,

|

where C is the chemical shift perturbation, Cmax is the chemical shift perturbation at saturation, KD is the dissociation constant, Ptot is the total concentration of the labeled protein, and Ltot is the total ligand concentration.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

All SPR measurements were performed on a Biacore T100 instrument at 25 °C in buffer HBS-EP (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20) at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. Approximately 2,000 response units of C90 was immobilized on a CM5 chip via standard amine coupling procedures, and a similar amount of CBag was immobilized on the chip as a negative control. For binding studies, 150 μl of His-Tom70ΔN was passed over immobilized C90 followed by dissociation of protein complexes for 10 min. The chip surface was regenerated by two 1-min pulses of buffer containing 2.5 m NaCl and 10 mm borate (pH 10). To calculate the KD, sensorgrams were fitted to a two-state (conformational change) binding model using BIAevaluation software. Competition experiments were performed by preincubating 1 μm His-Tom70ΔN with decapeptides derived from human Hsc70, Hsp90α, or Tom20. Protein mixtures were passed over C90 followed by dissociation and regeneration as described. The KD of peptide binding to Tom70 was calculated as half the concentration of peptide producing half-maximal competition.

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were maintained in DMEM containing 4.5 g/liter glucose, 36 mg/liter pyruvate, 2 mm glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Where indicated, the cells were seeded at a density of 3.75 × 103/cm2 the day before transfection and transfected with 50 nm control nonsilencing siRNA or siRNA against Tom70 (Dharmacon) overnight, trypsinized, diluted at an appropriate density the next day, and harvested 3 days after transfection for the isolation of mitochondria. Mitochondria were isolated from HeLa cells as described (13), and the targeting of cell-free translated proteins to mitochondria was performed as described (11). Where indicated, mitochondria were incubated with antibodies against Tom20 at 400 μg/ml for 30 min at 4 °C and reisolated by centrifugation prior to import.

Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation

Mitochondria were cross-linked with 1 mm s-SMCC as described (13) and immunoblotted against Tom20, Tom70, and Tom22. For immunoprecipitation, full-length Tom20 or Tom70 were radiolabeled using cell-free translation and targeted to mitochondria as described (13). Mitochondria were then resuspended in buffer containing 10 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 220 mm mannitol, 70 mm sucrose, and 1 mm EDTA at 1 mg/ml, cross-linked with 1 mm s-SMCC followed by solubilization in PBS and 0.5% digitonin. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g, and the Tom20-Tom70 cross-link was immunoprecipitated from the supernatant with the addition of 2 mg/ml ovalbumin, antibodies specific for Tom20 or Tom70 (1:100), and protein A-agarose.

RESULTS

Tom70 Interacts with Tom20

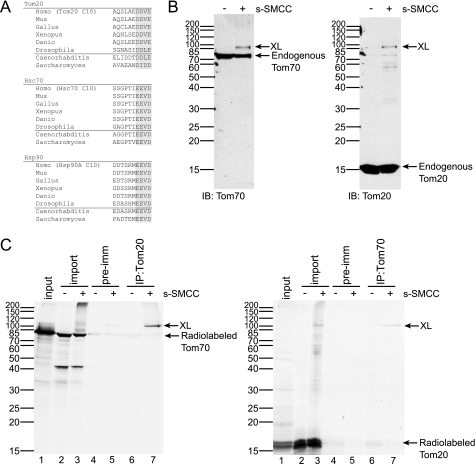

Human Tom70 was previously shown to exist as a monomer in its endogenous environment (13). Cross-linking of outer membrane components of HeLa cell mitochondria generated a Tom70 adduct at ∼100 kDa, above the 70-kDa Tom70 band (13). A similar adduct had not been observed with yeast Tom70, which instead formed a homodimeric cross-link at 150 kDa (33, 34). We hypothesized that the 100-kDa adduct may be an internal cross-link of the monomeric Tom70, or it may represent a heterodimeric cross-link with a smaller component of the outer mitochondrial membrane. We therefore examined possible candidates on the outer membrane to identify the interacting partner of Tom70. The only TOM proteins that could produce an adduct of that size were Tom20 and Tom22, and their sequences were analyzed. In the sequence alignment of the C terminus of Tom20, we found that human Tom20 ends with a DDVE sequence that is very similar to the EEVD motif at the C terminus of the chaperones Hsc70/Hsp70 and Hsp90 (Fig. 1A). The EEVD motif is an essential binding site for TPR clamp domains found in co-chaperones, including Tom70 (8, 10). It is possible that the Tom20 C-terminal DDVE sequence binds Tom70 as a mimic of the chaperone EEVD motif. Although the EEVD motif is conserved between human and yeast Hsp70 and Hsp90, the DDVE motif of Tom20 is most conserved in chordates (Fig. 1A). The motif is not found in Tom22, which also had no other predicted interaction sequences. This suggests that in humans Tom20 might interact with Tom70 in a manner similar to the chaperones, a mechanism that would be evolutionarily recent.

FIGURE 1.

The interaction between Tom70 and Tom20 on the outer mitochondrial membrane. A, alignment of the C-terminal motifs of Tom20, Hsc70, and Hsp90α. Peptides that consist of the last 10 residues of human Tom20, Hsc70, and Hsp90α are denoted as Tom20 C10, Hsc70 C10, and Hsp90A C10, respectively. B, 20 μg of mitochondria isolated from HeLa cells were cross-linked with 1 mm s-SMCC, resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting for Tom70 (left panel) and Tom20 (right panel). C, left panel, radiolabeled full-length Tom70 (lane 1) was inserted into 80 μg of HeLa mitochondria and treated with Me2SO or 1 mm s-SMCC (25% of reaction in lanes 2 and 3). Mitochondria were then solubilized by 0.5% digitonin, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) using preimmune serum (pre-imm, lanes 4 and 5) or an antibody specific for Tom20 (lanes 6 and 7). The reactions were subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The position of the immunoprecipitated cross-link (XL) is indicated. Right panel, experiment performed as in the left panel, but with radiolabeled full-length Tom20 and immunoprecipitated with antibody specific for Tom70.

As described previously (13), we cross-linked the outer membrane components in HeLa mitochondria with a membrane-impermeable cross-linker, s-SMCC, and detected Tom70 and its 100-kDa adduct by immunoblotting for Tom70 (Fig. 1B, left panel). Upon immunoblotting for Tom20, a main cross-link band was also observed at 100 kDa (Fig. 1B, right panel). No 100-kDa adducts were observed with the Tom22 antibody (data not shown). It was still possible that the 100-kDa Tom70 adduct was an internally cross-linked form; however, the exact co-migration on SDS-PAGE of the Tom70 and Tom20 adducts suggested that they represented the same Tom70-Tom20 complex.

The identity of the 100-kDa band as a heterodimeric cross-link between Tom70 and Tom20 was confirmed by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1C). Radiolabeled Tom70 was generated by cell-free translation and targeted to HeLa mitochondria. When the mitochondria were reisolated and cross-linked as above, labeled Tom70 formed a 100-kDa cross-link that, after solubilization, was immunoprecipitated by antibody specific for Tom20 (Fig. 1C, left panel, XL). Similarly, the 100-kDa cross-link formed by radiolabeled Tom20 was immunoprecipitated by Tom70 antibody (Fig. 1C, right panel, XL). Therefore, we have evidence for a direct interaction between the two import receptors, Tom70 and Tom20, on the outer mitochondrial membrane.

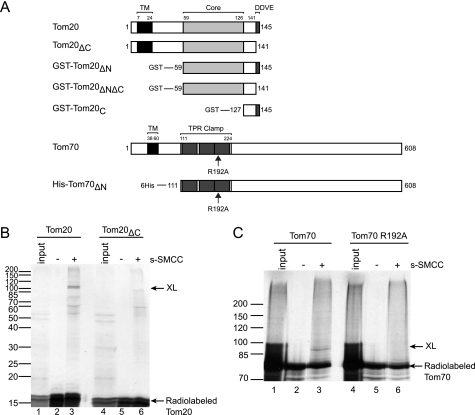

Tom20-Tom70 Interaction Sites

The Tom20 C-terminal DDVE motif may be the binding site for the Tom70 TPR clamp domain. To test this hypothesis, a series of Tom20 and Tom70 mutants were constructed and are presented in Fig. 2A. We first created a C-terminal deletion mutant of Tom20 that lacks the four-residue DDVE motif (Tom20ΔC) and compared it with its full-length counterpart by cross-linking to mitochondrial outer membrane proteins (Fig. 2B). Although radiolabeled Tom20ΔC was targeted and inserted into the outer membrane, at levels comparable with wild type, the 100-kDa cross-link with Tom70 was greatly reduced (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 3 and 6). Similarly, we generated a point mutation in the TPR clamp domain of human Tom70, R192A, which was previously shown to disrupt chaperone-Tom70 interactions in co-precipitation assays (10, 13). Again, the point mutation did not affect the integration of Tom70 into the outer mitochondrial membrane, but it abolished the formation of the 100-kDa cross-link with Tom20 (Fig. 2C, compare lanes 3 and 6). We conclude that the Tom20-Tom70 interaction likely requires the DDVE motif and the TPR clamp domain in the respective proteins on the membrane.

FIGURE 2.

The Tom20-Tom70 interaction was mediated by the DDVE motif and the TPR clamp. A, schematic diagram of Tom70 and Tom20 mutants used in this study. Transmembrane domains (TM) are denoted in black. Regions important for the Tom20-Tom70 interaction (DDVE motif in Tom20 and TPR clamp in Tom70) are denoted in dark gray. The structurally stable core region of Tom20 (residues 59–126) is denoted in light gray. B, full-length Tom20 (WT or ΔC) was radiolabeled by cell-free translation (10% input translation in lanes 1 and 4) and treated with Me2SO (lanes 2 and 5) or 1 mm s-SMCC (lanes 3 and 6) after insertion into HeLa mitochondria, followed by 12% SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. C, experiment performed as in B, but with radiolabeled full-length Tom70 (WT or R192A), and resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE. Lanes 1–3 were identical to those of Fig. 5C in Fan et al. (13) but at a higher exposure.

To better characterize the Tom20-Tom70 interaction and define a Tom20 fragment sufficient for binding, we performed experiments using purified proteins. Previous work by Abe et al. (31) showed that rat Tom20 consists of a structurally stable core region (residue 59–126) and more dynamic stretches spanning residues 50–58 and 127–145. Because the DDVE motif of Tom20 was required for the interaction with Tom70, a cytosolic Tom20 fragment containing the core to the C terminus (residues 59–145) was purified as a GST fusion protein (GST-Tom20ΔN) (Fig. 2A). The corresponding C-terminal deletion mutant lacking the DDVE motif was also purified (GST-Tom20ΔNΔC). As interactors, the previously characterized His-tagged cytosolic region (residues 111–608) of Tom70 (His-Tom70ΔN) and its R192A mutant (His-R192AΔN) were used (Fig. 2A) (10, 13). First, we reconstituted the interaction between the purified proteins using co-precipitation assays. His-Tom70ΔN showed significant binding to GST-Tom20ΔN immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads compared with the negative control with GST (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 7 and 9). However, the amount of His-R192AΔN recovered by GST-Tom20ΔN was not significantly different from background binding to GST (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 8 and 10). We also compared GST-Tom20ΔN with its C-terminal deletion mutant, GST-Tom20ΔNΔC. As expected, whereas GST-Tom20ΔN was able to recover a significant amount of His-Tom70ΔN, the GST-Tom20ΔNΔC mutant only recovered a trace amount of His-Tom70ΔN, similar to the negative controls (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 7 and 8). In addition, the membrane anchors of Tom70 and Tom20 are not required for the interaction. These results confirm that the Tom20-Tom70 interaction observed on the outer mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 2, B and C) is indeed due to direct contact, likely via the hypothesized interaction site in the Tom70 TPR clamp domain.

FIGURE 3.

Two regions of Tom20 are responsible for the interaction with Tom70. A, His-Tom70ΔN (WT or R192A) was co-precipitated either with unloaded glutathione-Sepharose (lanes 5 and 6) or with purified GST fusion proteins (GST, lanes 7 and 8; or GST-Tom20ΔN, lanes 9 and 10) and glutathione-Sepharose, followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. B, similarly, His-Tom70ΔN (WT) was co-precipitated either with unloaded glutathione-Sepharose (lane 5) or with purified GST fusion proteins (GST, lane 6; GST-Tom20ΔN, lane 7; or GST-Tom20ΔNΔC, lane 8) and glutathione-Sepharose, followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. C, overlay of 15N-1H HSQC region of Tom20ΔN (residues 59–145) shows specific binding to Tom70. The starting concentration of Tom20ΔN was 600 μm (red), and Tom70ΔN was titrated to equimolar amounts in two successions: green, the midpoint with 290 μm Tom20ΔN and 145 μm Tom70ΔN; and blue, 190 μm Tom20ΔN and 190 μm Tom70ΔN. D, a homology model of human Tom20 was generated using the rat Tom20 solution structure as a template (Protein Data Bank code 1OM2) to map NMR perturbations. Residues that displayed significant changes in chemical shifts are shown as red spheres and labeled. The presequence binding groove is indicated and highlighted in blue. Seph, Sepharose.

We then carried out NMR measurements of 15N-labeled Tom20ΔN alone and with the addition of unlabeled Tom70ΔN. The 1H-15N correlation spectrum of Tom20ΔN alone showed well dispersed peaks, some of which shifted upon addition of Tom70ΔN, indicating specific binding (Fig. 3C and supplemental Fig. S1). To identify the binding surface, we generated a homology model of human Tom20 based on the structure of the almost identical rat homolog using SwissModel (31, 35, 36). Mapping of the NMR chemical shift perturbations onto the Tom20 model structure identified two main interaction regions (Fig. 3D). As expected, the first region was at the C terminus of Tom20, comprising residues Ala-140, Glu-141, and Glu-145. We should note that chemical shift changes of Asp-142, Asp-143, and Val-144 could not be reliably traced during the titration because of overlap with other signals. In addition, residues Gly-89, Val-90, Asp-91, and His-92 were also affected, revealing a second binding site in the core domain of Tom20. However, the 1H-15N correlation spectrum of labeled Tom20ΔNΔC showed no changes upon addition of Tom70ΔN (supplemental Fig. S2), demonstrating that this internal region alone cannot initiate binding to Tom70. Nonetheless, although the C-terminal DDVE motif may be the primary site of the Tom20-Tom70 interaction, the internal region of Tom20 is likely to serve as a secondary contact point that could further strengthen the overall interaction. The internal region is on the opposite side from the presequence binding site of Tom20 (31, 37) (Fig. 3D). Because the Tom20 C terminus is also not involved in presequence recognition (31, 37), Tom70 could contact both interaction sites on Tom20 without blocking Tom20 receptor function.

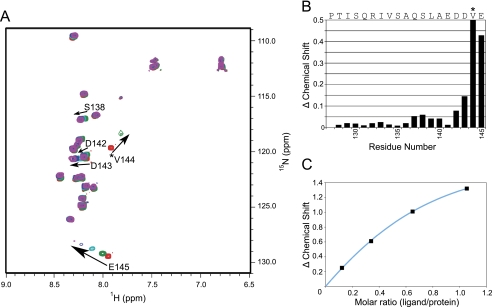

Based on the crystallographic structures of contact sites between Hsp70 or Hsp90 EEVD motifs and the TPR clamp domains of Hop, electrostatic interactions around the Asp residue and hydrophobic contacts around the Val residue are crucial for binding (8). Alanine scanning mutagenesis and peptide binding analysis have shown that hydrophobic residues upstream of the EEVD motif contribute to the binding affinities: the Pro, Thr, and Ile residues of the Hsc70/Hsp70 sequence PTIEEVD and the Met residue in the Hsp90 sequence MEEVD (9). Unlike the Hop domains, Tom70 appears to bind both Hsc70 and Hsp90 (10), but the residues upstream of the Tom20 DDVE motif (AQSLAEDDVE) may still take part in the interaction. To test this, we performed an NMR titration of the 15N-labeled C-terminal peptide region, Tom20C (residue 127–145; Fig. 2A) with increasing amounts of Tom70ΔN (Fig. 4A). The chemical shift changes were plotted for each residue of Tom20C to illustrate their involvement in binding (Fig. 4B). Val-144 was most significantly affected, because its backbone amide peak disappeared after the addition of a substoichiometric amount of Tom70ΔN (Fig. 4A). The terminal residue Glu-145 showed the second most significant change in chemical shift, whereas Asp-142 and Asp-143 of the DDVE motif showed moderate changes. The upstream residues Gln-137, Ser-138, Leu-139, and Ala-140 were only marginally affected by the binding of Tom70ΔN (Fig. 4, A and B). This pattern is in agreement with previous studies on the EEVD motif with the largest contributions from the terminal Val-Glu (8, 9). Also, fit of the chemical shift changes for the terminal residue Glu-145 resulted in a KD estimate of ∼100 μm for the Tom20C-Tom70 interaction (Fig. 4C), in the same range as affinities of EEVD peptide binding to the TPR1 and TPR2A domains of Hop (8). As for the Hop domains, secondary contacts of the internal Tom20 site identified above may increase the binding affinity of the full-length proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Contribution of Tom20 residues to Tom70 binding. A, overlay of 15N-1H correlation spectra of Tom20C (residue 127–145) upon binding to His-Tom70ΔN. The starting concentration of Tom20C was 620 μm (red) and titrated with Tom70ΔN to saturation in four successions: green, 515 μm Tom20C and 63 μm Tom70ΔN; cyan, 400 μm Tom20C and 135 μm Tom70ΔN; blue, 310 μm Tom20C and 199 μm Tom70ΔN; and purple, 240 μm Tom20C and 250 μm Tom70ΔN. Backbone amide peaks with the largest changes in chemical shift are labeled. B, plot of amide chemical shift changes of Tom20C upon binding Tom70ΔN. The largest change was attributed to Val-144, denoted by an asterisk, whose backbone amide peak disappeared after a substoichiometric addition of Tom70 and arbitrarily shown at 0.5 ppm. C, plot of the magnitude of 15N chemical shift changes for Glu-145 as a function of molar ratio. KD of the binding was estimated from a fit as ∼100 μm.

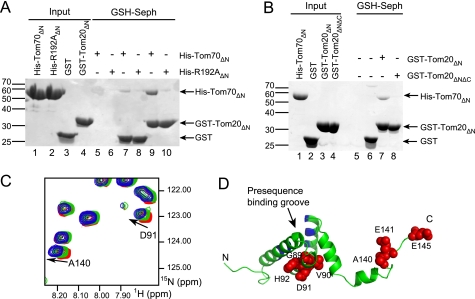

Tom20 Competes with Chaperones for Tom70 Binding

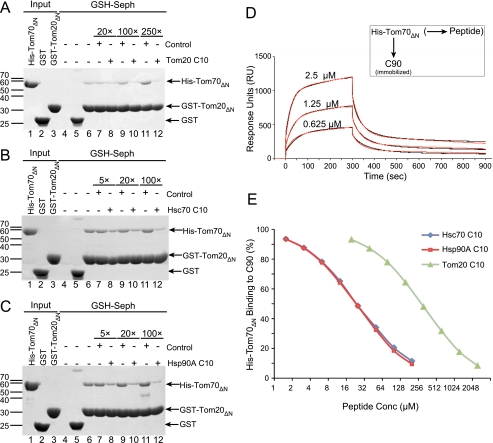

The Tom20 C terminus interaction must compete with the Hsc70 and Hsp90 C termini for binding to the Tom70 TPR clamp domain. As a direct test of this and to compare their relative binding strengths, we used decapeptides from the C terminus of Tom20, Hsc70, and Hsp90 (Fig. 1A) as competitors in our co-precipitation assay. As expected, the Tom20-derived decapeptide AQSLAEDDVE (Tom20 C10) began to show competition for His-Tom70ΔN when added in 20-fold excess of immobilized GST-Tom20ΔN (39% binding compared with control; Fig. 5A). Maximal inhibition was observed when Tom20 C10 was added in 250-fold excess. The control peptide EVDDEALSQA (reverse of Tom20 C10) with an identical charge and mass did not significantly compete for the Tom20-Tom70 binding at all concentrations used (Fig. 5A), in agreement with sequence-specific binding of Tom20 C10. A similar pattern of competition was observed with Hsc70 and Hsp90 decapeptides, but at lower concentrations of peptides. Competition of Tom20-Tom70 binding was observed with as little as a 5-fold excess of Hsc70 C10 (SSGPTIEEVD, 33% binding) or Hsp90A C10 (DDTSRMEEVD, 31% binding), and only a 100-fold excess was required to reach maximal competition (Fig. 5, B and C). These data suggest that Tom20 competes with Hsc70 and Hsp90 for the same binding site on Tom70 and that the chaperones may have higher binding affinities.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of C-terminal affinities for Tom70 between Tom20 and the chaperones. A, His-Tom70ΔN (WT) was co-precipitated either with unloaded glutathione-Sepharose (lane 4) or with purified GST fusion proteins (GST, lane 5; or GST-Tom20ΔN, lanes 6–12) and glutathione-Sepharose as above. Where indicated, control (EVDDEALSQA) and Tom20 C10 peptides were added at 20-fold (lanes 7 and 8), 100-fold (lanes 9 and 10), or 250-fold molar excess (lanes 11 and 12). B and C, experiments were repeated with Hsc70 C10 peptide (B) and Hsp90A C10 peptide (C) at an excess of 5-fold (lanes 7 and 8), 20-fold (lanes 9 and 10), or 100-fold (lanes 11 and 12). D, representative SPR association and dissociation curves (black lines) of His-Tom70ΔN at the indicated concentrations binding to immobilized C90. The full range of His-Tom70ΔN concentrations tested was from 0.315 to 10 μm. Background binding to unrelated protein (CBag) was subtracted. Curves were fit to a two-state conformational change model (red lines) for determination of association and dissociation rates and KD. E, 1 μm His-Tom70ΔN was incubated with the indicated concentrations of Hsc70 C10, Hsp90A C10, and Tom20 C10 peptides, and binding to immobilized C90 was analyzed as above. Binding is represented as a percentage of that in the absence of competitor peptide. Seph, Sepharose; Conc, concentration.

Competitive binding of Tom20, Hsc70, and Hsp90 to Tom70 implies that several populations of complexed and unbound Tom70 may exist in cells. The relative proportions of each complex would depend on binding affinities of each protein. To obtain a quantitative measure of binding, we performed SPR experiments. Similar to earlier experiments on the Hop TPR clamp domains (9), a C-terminal fragment of Hsp90 (C90), known to bind Tom70 (10), was immobilized on a sensor chip. When His-Tom70ΔN was passed over the chip, binding was observed with clear association and dissociation phases and with concentration dependent increases in binding (Fig. 5D). The association and dissociation rates were best fit with a two-state conformational change model, resulting in an overall KD of 1.14 μm, which was determined from the kinetic rate constants. This is close to the values reported for the Hsp90 interaction with Hop (9) ranging from 1 to 6 μm for full-length to shorter fragments of Hsp90. The multiphasic binding may reflect conformational changes in Tom70 upon chaperone binding, as has been reported for the yeast homolog Tom71 (38). As expected, no binding of the His-R192AΔN mutant was detected (data not shown).

The interactions between Tom70 and either Tom20, Hsc70, or Hsp90 were then compared using peptide competition SPR experiments. The decapeptides used in the co-precipitation assays were incubated at different concentrations with His-Tom70ΔN before passage over immobilized C90. As expected, Tom70 binding was reduced with increased Hsp90A C10 concentrations (Fig. 5E). The estimated KD of Hsp90A C10 peptide binding was 12.5 μm. This was somewhat weaker than the affinity for the longer C90 fragment, suggesting that like Tom20, Hsp90 may also have secondary interactions with Tom70 beyond the C-terminal motif. Nonetheless, competition of Tom70 binding was also observed with both the Hsc70 C10 and Tom20 C10 peptides, and close to maximum competition could be achieved (Fig. 5E). Only marginal competition was observed with the control reverse peptide (not shown). The KD was estimated to be 12.5 μm for the Hsc70 peptide and 156 μm for the Tom20 peptide. These values are consistent with the NMR titration and GST fusion co-precipitation experiments using longer Tom20 fragments. Thus, Hsc70 and Hsp90 appear to have similar binding strengths to Tom70, whereas Tom20 is weaker by ∼1 order of magnitude. However, both Tom70 and Tom20, unlike the chaperones, are membrane-anchored, which would greatly increase their effective local concentration relative to each other on the outer mitochondrial membrane. These conditions would favor Tom20-Tom70 interactions and result in a balanced competition between anchored Tom20 and the unanchored but more strongly binding chaperones. Our results suggest that the C-terminal peptide sequence of Tom20 is both necessary and sufficient for interaction with the TPR clamp domain of Tom70. The DDVE motif of Tom20 interacts in the same manner as the EEVD motif of the chaperones, albeit at a lower affinity calibrated to compensate for high effective concentration.

Tom20 Binding Is Required for Tom70 Function

Interaction of Hsc70 and Hsp90 with the Tom70 TPR clamp domain initiates recognition of chaperone-bound precursor by Tom70. Competition of Tom20 for the same site on Tom70 does not prevent this mechanism, likely because of the somewhat lower binding affinity. We nonetheless proposed that the Tom20-Tom70 contact has a function in dissociating chaperones from Tom70 for translocation of the precursors across the outer membrane. If so, disrupting Tom20 should affect the import of precursors recognized by Tom70, as well as those bound directly by Tom20. Because Tom70 does not interact with the functional surface of Tom20, disrupting Tom70 may have no effect on Tom20-dependent import, but only on Tom70-dependent precursors.

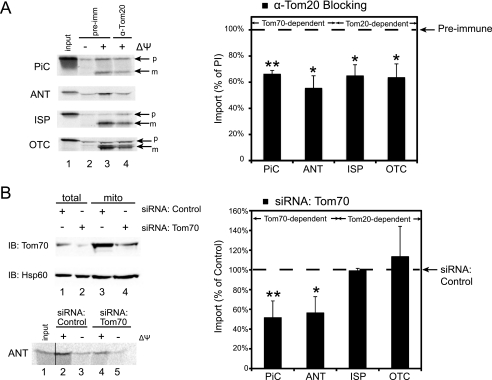

We tested these ideas directly with mitochondrial import assays. Because functional mitochondria could not be reproducibly obtained from HeLa cells after siRNA-mediated Tom20 knock-down, mitochondria were isolated from untransfected HeLa cells and then incubated with antibodies against Tom20 to block the receptor function. The mitochondria were then reisolated, and their ability to import various precursors was tested. The import of radiolabeled cell-free translated precursors was dependent on the membrane potential of the mitochondria and verified by protection from externally added proteinase K (Fig. 6A). As expected, antibody blocking of Tom20 significantly reduced the import of the two Tom20-dependent preproteins tested, Rieske iron-sulfur protein (ISP) and OTC, to ∼65% of control reactions treated with preimmune serum. Intriguingly, antibody blocking of Tom20 also impaired the Tom70 import pathway. The import of Tom70-dependent preproteins, PiC and ANT, were decreased significantly to 65 and 55% of control, respectively. These results contrasted with previous work that used the C90 fragment of Hsp90 to compete all interactions with the Tom70 TPR clamp domain, which only affected import of Tom70-dependent precursors (10). The Tom20 antibody used here should block binding of Tom20, but not Hsc70 or Hsp90, to Tom70; however, an impairment of Tom70-dependent import was still observed. To rule out an overall block of the GIP itself, the targeting of Tom70 was tested. Insertion of newly synthesized Tom70 requires the GIP but not the function of the Tom20 or Tom70 receptors (39). We now found that antibody blocking of Tom20 had no significant effect on Tom70 targeting (supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that the GIP is fully accessible.

FIGURE 6.

Tom70-Tom20 interaction is required for Tom70 function but not for Tom20 function. A, left panel, mitochondria were isolated from HeLa cells and treated with preimmune serum (pre-imm, lanes 2 and 3) or antibody against Tom20 (lane 4). Radiolabeled preprotein (lane 1) was then imported in the presence (lanes 3 and 4) or absence (lane 2) of Δψ, digested by proteinase K, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Right panel, quantification of the preprotein import, expressed as a percentage of import into mitochondria pretreated with preimmune serum in the presence of Δψ (left panel, lane 3; right panel, dashed line). Import of all preproteins was statistically different from control, with p values for PiC, ANT, ISP, and OTC calculated to be 0.002, 0.015, 0.019, and 0.026, respectively. B, upper left panel, HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (lane 1) or siRNA against Tom70 (lane 2), and their mitochondria were isolated (lanes 3 and 4). The samples were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) for Tom70 and a mitochondrial protein, Hsp60, as a loading control. Lower left panel, radiolabeled preprotein (lane 1) was imported into HeLa mitochondria with normal (lanes 2 and 3) or knockdown (lanes 4 and 5) of Tom70 expression, in the presence (lanes 2 and 4) or absence (lanes 3 and 5) of Δψ, digested by proteinase K, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Right panel, quantification of preprotein import, expressed as a percentage of import into mitochondria with normal Tom70 expression in the presence of Δψ (lower left panel, lane 2; right panel, dashed line). Import of Tom70-dependent preproteins, PiC and ANT, were statistically different from control, but not for Tom20-dependent proteins ISP and OTC. The corresponding p values were calculated to be 0.003, 0.044, 0.58, and 0.53, respectively. All of the p values were calculated based on a Student's t test with a minimum of three independent experiments (*, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01; n ≥ 3).

We wondered whether we could observe the same inter-receptor dependence with Tom70. In this case, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA against Tom70 to knock down the expression of the receptor before mitochondria were isolated for import assays. Control mitochondria were isolated from cells transfected with nonsilencing siRNA duplexes. A clear reduction in Tom70 levels was observed after the knockdown, in the total cell lysate and the isolated mitochondria (Fig. 6B). As predicted, the Tom70 import pathway was adversely affected by knockdown of Tom70 expression. Levels of PiC and ANT import were both decreased significantly to ∼55% of reactions with control nonsilenced mitochondria. In contrast, the Tom20 import pathway did not appear to be affected. Levels of ISP and OTC import were 100 and 115% of the control and not significantly different. Our results led us to conclude that Tom70 requires Tom20 having the DDVE interaction motif for its import functions, but not vice versa.

DISCUSSION

This report suggests a functional interaction between the human Tom70 and Tom20, which is primarily mediated by the TPR clamp of Tom70 and the DDVE motif at the C terminus of Tom20. Even though an interaction between the two mitochondrial import receptors was previously reported in yeast, the yeast homolog of Tom20 did not contain the DDVE motif required for interaction with the TPR clamp (24). This may be why this interaction could not be consistently observed in most studies with yeast (16, 18, 20). A yeast two-hybrid interaction between rat Tom70 and Tom20 was reported but not further characterized (27). However, recent work with the mammalian receptors showed that they interact with unexpected binding partners, such as the interaction of Tom70 with the internal EELD sequence of Mcl-1 and that of Tom20 with the TPR co-chaperone AIP (14, 28). A putative import receptor in mammals, Tom34, was also shown to interact with the chaperone Hsp90 via its TPR clamp domain, although the role of this receptor in preprotein import remains controversial (40–44). Here, we demonstrate that Tom20 interacts with Tom70, possibly as a mechanism to displace the chaperones by competition. This mechanism may coordinate the dissociation of Tom70 complexes with preprotein translocation through the GIP.

The TPR clamp domain of Tom70 was originally identified as an important structural element for interacting with the chaperones Hsc70 and Hsp90 (8, 10). Our results identify Tom20 as a third interactor at this site. Affinity measurements suggest that Hsc70 and Hsp90 bind similarly (KD from 1.14 to 12.5 μm), with affinities close to those reported for TPR clamp domains of Hop (KD between 1 and 18 μm) (8, 9) and of the yeast Ssa1-Tom70 interaction (3.8 μm) (45). The Tom20-Tom70 interaction appears to be somewhat weaker (KD = 100 to 156 μm) but is likely compensated by a high effective concentration on the membrane. Immunoblot comparisons of purified protein and HeLa cell lysates (not shown) suggested that Tom70 constituted roughly 0.1% of Triton X-100 soluble proteins, with Tom20 expected to be similar. The estimated cellular concentrations of Hsc70 and Hsp90 are in the range of 30 μm or 1% soluble protein (for example Refs. 46 and 47), consistent with a transient contact with Tom70. Overall concentrations of Tom70 may be 10-fold lower; however, the receptor is limited to the narrow volume of the mitochondrial outer membrane, a very small fraction of the cell volume. In addition, Tom70 and Tom20 are both membrane-anchored with limited freedom of movement. These factors will greatly favor the Tom20-Tom70 interaction with effective concentrations plausibly in the 100 μm range. A Tom20-Tom70 affinity also ∼100 μm would result in an even balance between Tom20-Tom70 and chaperone-Tom70 complexes. The exchange between such complexes is likely to contribute to Tom70 function.

The affinities of the Tom70 interactors may be determined in part by the residues upstream of the EEVD and DDVE motifs. Hydrophobic residues upstream of the EEVD motif for the chaperones (PTIEEVD for Hsc70 and MEEVD for Hsp90) were shown to enhance the affinity of TPR clamp binding (9). In contrast, those of Tom20 (QSLAEDDVE) did not seem to participate in the interaction with Tom70 in our NMR experiments. In particular, Glu-141 showed almost no chemical shift difference upon Tom70 binding, whereas Gln-137, Ser-138, Leu-139, and Ala-140 were only mildly affected (Fig. 4B). The weaker affinity of Tom20 binding relative to Hsc70 and Hsp90 may be due to the lack of a hydrophobic residue immediately upstream of the DDVE motif in position 141 that could form a stabilizing contact with Tom70. A separate NMR experiment with the cytosolic domain of Tom20 showed that in addition to the C terminus, another region in the core domain also participated in the interaction with Tom70 (Fig. 3, C and D, and supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, previous studies by Haucke et al. (24) identified residues Phe-117 and Tyr-118 of yeast Tom20 to be essential for interacting with Tom70, and the corresponding residues in the human homolog (Leu-93 and Thr-94) are adjacent to the internal site (Gly-89, Val-90, Asp-91, and His-92) mapped by NMR experiments. It is possible that Tom20 strengthens its interaction with Tom70 via an internal site that is distinct from the C-terminal region, contributing further to the function of the receptors.

As proposed, compromising Tom20 decreased Tom70-mediated preprotein import in our antibody blocking experiment, indicating that the Tom20-Tom70 interaction may be an important step (Fig. 6). Our findings suggest a mechanistic explanation for earlier antibody blocking observations (27). Preprotein targeting to Tom70 is supported by the chaperone-Tom70 interaction but can be reconstituted using the purified Tom70-soluble fragment and does not require Tom20 (10). Antibody blocking of Tom20 would not inhibit chaperone-mediated preprotein targeting to Tom70, so a later step must be inhibited. The competition between Tom20 and chaperones for the single Tom70 TPR clamp domain (Fig. 5) suggests that Tom20 binding and hence displacement of chaperones from Tom70 may have a key role in preprotein import. This leads to our new model of the Tom70 import pathway. Under resting conditions, Tom70 can interact dynamically with Tom20 on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Preprotein is bound by Hsc70 and Hsp90 in the cytosol, and this multichaperone complex docks on Tom70 via the EEVD-TPR clamp interaction, displacing Tom20. After chaperone docking, Tom70 directly binds the preprotein, which is then released by the chaperones after ATP hydrolysis. At this step, we propose that Tom20 binding occurs again to displace the chaperones, as a mechanism to facilitate the release of preproteins from the Tom70 complex for translocation.

Because chaperones play an important role in preventing hydrophobic preproteins from aggregation, we postulate that the release of preproteins by chaperones only occurs when the preproteins are close enough to the GIP for translocation. Upon accumulation at the GIP during import into yeast mitochondria, the Tom70-dependent ADP/ATP carrier was found to be in close proximity of Tom20 and Tom70 (23). There was evidence that some fraction of yeast Tom20 stably associates with the GIP, although Tom70 remains separate (15, 16, 19, 20). There have been similar observations in mammals where the rat and monkey homologs of Tom20 were also found to co-migrate with GIP components Tom40 and Tom22 at ∼400 kDa on Blue Native PAGE (25, 26), whereas human Tom70 mostly migrates as a monomer (13). Furthermore, antibodies against rat Tom70 could co-immunoprecipitate rat Tom20, Tom22 and Tom40, but in a salt-sensitive manner (27). C-terminally truncated rat Tom20 was able to complement yeast Tom20 (48), consistent with the DDVE interaction being evolutionarily recent. Taken together with our results, these observations suggest that the GIP-associated Tom20 can transiently link Tom70 with the GIP at a step after preprotein binding to the receptor. This link would simultaneously displace chaperones from the preprotein-Tom70 complex, allowing the preprotein to advance to the GIP. An interesting speculation is that additional mechanisms promote the release of preprotein from Tom70 to the GIP, perhaps by conformational changes in the receptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Young and Gehring laboratories.

The work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- TOM

- translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane

- ANT

- adenine nucleotide transporter

- GIP

- general import pore

- ISP

- Rieske iron-sulfur protein

- OTC

- ornithine transcarbamylase

- PiC

- phosphate carrier

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- s-SMCC

- succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate

- TPR

- tetratricopeptide repeat

- CHAPSO

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sickmann A., Reinders J., Wagner Y., Joppich C., Zahedi R., Meyer H. E., Schönfisch B., Perschil I., Chacinska A., Guiard B., Rehling P., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13207–13212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reinders J., Zahedi R. P., Pfanner N., Meisinger C., Sickmann A. (2006) J. Proteome Res. 5, 1543–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taylor S. W., Fahy E., Zhang B., Glenn G. M., Warnock D. E., Wiley S., Murphy A. N., Gaucher S. P., Capaldi R. A., Gibson B. W., Ghosh S. S. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pagliarini D. J., Calvo S. E., Chang B., Sheth S. A., Vafai S. B., Ong S. E., Walford G. A., Sugiana C., Boneh A., Chen W. K., Hill D. E., Vidal M., Evans J. G., Thorburn D. R., Carr S. A., Mootha V. K. (2008) Cell 134, 112–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foury F., Roganti T., Lecrenier N., Purnelle B. (1998) FEBS Lett. 440, 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson S., Bankier A. T., Barrell B. G., de Bruijn M. H., Coulson A. R., Drouin J., Eperon I. C., Nierlich D. P., Roe B. A., Sanger F., Schreier P. H., Smith A. J., Staden R., Young I. G. (1981) Nature 290, 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chacinska A., Koehler C. M., Milenkovic D., Lithgow T., Pfanner N. (2009) Cell 138, 628–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scheufler C., Brinker A., Bourenkov G., Pegoraro S., Moroder L., Bartunik H., Hartl F. U., Moarefi I. (2000) Cell 101, 199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brinker A., Scheufler C., Von Der Mulbe F., Fleckenstein B., Herrmann C., Jung G., Moarefi I., Hartl F. U. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19265–19275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young J. C., Hoogenraad N. J., Hartl F. U. (2003) Cell 112, 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan A. C., Bhangoo M. K., Young J. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33313–33324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhangoo M. K., Tzankov S., Fan A. C., Dejgaard K., Thomas D. Y., Young J. C. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 3414–3428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fan A. C., Gava L. M., Ramos C. H., Young J. C. (2010) Biochem. J. 429, 553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou C. H., Lee R. S., Yang-Yen H. F. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3952–3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Künkele K. P., Heins S., Dembowski M., Nargang F. E., Benz R., Thieffry M., Walz J., Lill R., Nussberger S., Neupert W. (1998) Cell 93, 1009–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dekker P. J., Ryan M. T., Brix J., Müller H., Hönlinger A., Pfanner N. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 6515–6524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahting U., Thun C., Hegerl R., Typke D., Nargang F. E., Neupert W., Nussberger S. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 959–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Wilpe S., Ryan M. T., Hill K., Maarse A. C., Meisinger C., Brix J., Dekker P. J., Moczko M., Wagner R., Meijer M., Guiard B., Hönlinger A., Pfanner N. (1999) Nature 401, 485–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kiebler M., Pfaller R., Söllner T., Griffiths G., Horstmann H., Pfanner N., Neupert W. (1990) Nature 348, 610–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meisinger C., Ryan M. T., Hill K., Model K., Lim J. H., Sickmann A., Müller H., Meyer H. E., Wagner R., Pfanner N. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2337–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Model K., Prinz T., Ruiz T., Radermacher M., Krimmer T., Kühlbrandt W., Pfanner N., Meisinger C. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 316, 657–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Model K., Meisinger C., Kühlbrandt W. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383, 1049–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Truscott K. N., Wiedemann N., Rehling P., Müller H., Meisinger C., Pfanner N., Guiard B. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7780–7789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haucke V., Horst M., Schatz G., Lithgow T. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 1231–1237 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki H., Okazawa Y., Komiya T., Saeki K., Mekada E., Kitada S., Ito A., Mihara K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37930–37936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abdul K. M., Terada K., Yano M., Ryan M. T., Streimann I., Hoogenraad N. J., Mori M. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276, 1028–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suzuki H., Maeda M., Mihara K. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 1895–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yano M., Terada K., Mori M. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 163, 45–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sondermann H., Scheufler C., Schneider C., Hohfeld J., Hartl F. U., Moarefi I. (2001) Science 291, 1553–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zara V., Palmieri F., Mahlke K., Pfanner N. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 12077–12081 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abe Y., Shodai T., Muto T., Mihara K., Torii H., Nishikawa S., Endo T., Kohda D. (2000) Cell 100, 551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Igura M., Ose T., Obita T., Sato C., Maenaka K., Endo T., Kohda D. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61, 514–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wiedemann N., Pfanner N., Ryan M. T. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 951–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Söllner T., Rassow J., Wiedmann M., Schlossmann J., Keil P., Neupert W., Pfanner N. (1992) Nature 355, 84–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. (2006) Bioinformatics 22, 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kiefer F., Arnold K., Künzli M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D387–D392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saitoh T., Igura M., Obita T., Ose T., Kojima R., Maenaka K., Endo T., Kohda D. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 4777–4787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li J., Qian X., Hu J., Sha B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23852–23859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ahting U., Waizenegger T., Neupert W., Rapaport D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chewawiwat N., Yano M., Terada K., Hoogenraad N. J., Mori M. (1999) J. Biochem. 125, 721–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang C. S., Weiner H. (2002) Arch Biochem. Biophys. 400, 105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Joseph A. M., Rungi A. A., Robinson B. H., Hood D. A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C867–C875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schlegel T., Mirus O., von Haeseler A., Schleiff E. (2007) Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 2763–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tsaytler P. A., Krijgsveld J., Goerdayal S. S., Rüdiger S., Egmond M. R. (2009) Cell Stress Chaperones 14, 629–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mills R. D., Trewhella J., Qiu T. W., Welte T., Ryan T. M., Hanley T., Knott R. B., Lithgow T., Mulhern T. D. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 388, 1043–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frydman J., Nimmesgern E., Ohtsuka K., Hartl F. U. (1994) Nature 370, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Terada K., Kanazawa M., Bukau B., Mori M. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 1089–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iwahashi J., Yamazaki S., Komiya T., Nomura N., Nishikawa S., Endo T., Mihara K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18467–18472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.