Abstract

Cullin 4B (CUL4B) is a scaffold protein that assembles cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase (E3) complexes. Recent studies have revealed that germ-line mutations in CUL4B can cause mental retardation, short stature, and many other abnormalities in humans. Identifying specific CUL4B substrates will help to better understand the physiological functions of CUL4B. Here, we report the identification of peroxiredoxin III (PrxIII) as a novel substrate of the CUL4B ubiquitin ligase complex. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry showed that PrxIII was among the proteins up-regulated in cells after RNAi-mediated CUL4B depletion. The impaired degradation of PrxIII observed in CUL4B knockdown cells was confirmed by Western blot. We further demonstrated that DDB1 and ROC1 in the DDB1-CUL4B-ROC1 complex are also indispensable for the proteolysis of PrxIII. In addition, the degradation of PrxIII is independent of CUL4A, a cullin family member closely related to CUL4B. In vitro and in vivo ubiquitination assays revealed that CUL4B promoted the polyubiquitination of PrxIII. Furthermore, we observed a significant decrease in cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in CUL4B-silenced cells, which was associated with increased resistance to hypoxia and H2O2-induced apoptosis. These findings are discussed with regard to the known function of PrxIII as a ROS scavenger and the high endogenous ROS levels required for neural stem cell proliferation. Together, our study has identified a specific target substrate of CUL4B ubiquitin ligase that may have significant implications for the pathogenesis observed in patients with mutations in CUL4B.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Genetic Diseases, Human Genetics, Protein Degradation, Proteomics, Ubiquitination, CUL4B, PrxIII

Introduction

E3 ubiquitin ligases catalyze the polyubiquitination of specific protein substrates, which targets them for degradation, and play a key role in regulating numerous additional cellular processes (1). The cullins are a family of evolutionarily conserved proteins that provide “scaffolding” for the largest known E3 ubiquitin ligases, the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases (2). There are seven members in the cullin family: CUL1, -2, -3, -4A, -4B, -5, and -7. Each member assembles a multisubunit E3 ligase by binding to a substrate-recruiting specificity factor and a RING finger protein, which activates the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (3–6). Each cullin-dependent E3 ligase can recruit various substrate proteins for ubiquitin-dependent degradation (7).

Although there is only a single Cul4 gene in lower organisms, two closely related paralogs, CUL4A and CUL4B, carry out the CUL4 function in mammalian cells (8). Both CUL4A and CUL4B can bind with the RING finger protein ROC1 (also known as Rbx1) at their C-terminal region and UV-damaged DNA-binding protein 1 (DDB1)2 at their N-terminal region (2). As an adaptor protein, DDB1 tethers different specificity factors to the core ligase complex, consisting of CUL4A/CUL4B and ROC1, which, in turn, recruits E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and mediates substrate protein ubiquitination (9–12).

Although CUL4A and CUL4B are 80% identical in their protein sequences, CUL4B has a unique N terminus that is 149 amino acids longer than CUL4A (13), suggesting that CUL4B may selectively ubiquitinate specifically recruited substrates. Recent genetic studies have identified mutations in CUL4B as the cause of X-linked mental retardation (XLMR) in humans (14–16). Supporting a distinct function of CUL4B in this disease, the N terminus of CUL4B assembles a specific ubiquitin ligase complex that targets the estrogen receptor α for degradation (17). These findings indicate that the CUL4B complex could operate as a distinct E3-ubiquitin ligase; therefore, it is important to identify the substrates that are specifically targeted by CUL4B ubiquitin ligase.

The present study aimed to identify the specific protein substrates for CUL4B. To accomplish this, we applied two-dimensional gel electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry to characterize the proteins that are differentially expressed in CUL4B-depleted HEK293 cells. Using this technique, we identified PrxIII as a novel and specific substrate of CUL4B E3 ubiquitin ligase.

The peroxiredoxins (Prxs) represent a family of thiol-specific antioxidant proteins that also participate in mammalian cell signal transduction (18–20). The human Prxs include six isoforms (PrxI to PrxVI), which are classified into three subgroups (2-Cys, atypical 2-Cys, and 1-Cys) based on the number and positions of the Cys residues that participate in catalysis (21). PrxIII belongs to the 2-Cys subgroup and contains both N- and C-terminal Cys residues (22). During PrxIII catalysis, there are two active sites where Cys residues are oxidized by peroxide substrates to form disulfide bonds (23).

Here, we have provided experimental evidence that CUL4B, but not CUL4A, mediates the proteasomal degradation of PrxIII. In addition, we have shown that the integrity of DDB1-CUL4B-ROC1 is essential for promoting CUL4B-mediated PrxIII degradation. Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo ubiquitination assays revealed that CUL4B promotes polyubiquitination of PrxIII. Moreover, the elevation of PrxIII exhibited decreased levels of cellular ROS and was resistant to the hypoxia and H2O2-induced apoptosis in response to CUL4B silencing. Collectively, our findings identify a novel substrate of CUL4B ubiquitin ligase and may provide insight into the pathogenesis caused by CUL4B deficiency in humans.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Cultures, Plasmids, and Protein Extracts

HEK293 and HeLa cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus penicillin and streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The details for the construction of pcDNA3.1/myc-His A-CUL4B plasmids has been described elsewhere (13). Construction of pcDNA3.1/myc-His-PrxIII was accomplished by subcloning a PCR-amplified PrxIII fragment in-frame into the pcDNA3.1-myc-His A vector (Invitrogen) between the BamHI and EcoRI sites using HEK293 cDNA as a template. The cultures were harvested upon reaching 80–90% confluence. The cell pellets were dissolved in lysis buffer (50 μl/106 cells) containing 7 mm urea, 2 m thiourea, 4% CHAPS (W/V), 2% Pharmalyte, 65 mm DTT, and 1% mixture (v/v). The supernatant was then collected and used for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. The protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard (24).

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Approximately 450 μg of protein was resuspended in a rehydration solution (8 m urea, 2% CHAPS, 65 mm DTT, 0.2% Pharmalyte (pH range 4–7), and 0.2% bromphenol blue) and applied to 18-cm pH 4–7 linear IPG strips (General Electric) for isoelectrofocusing (25). Isoelectrofocusing was performed using an Ettan IPGphor instrument (GE Healthcare), and the proteins in the IPG strips were subsequently placed on a 12% uniform SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The gels were silver-stained and scanned with an Image Scanner in transmission mode, after which image analysis was conducted with two-dimensional PDquest (Bio-Rad). The two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was repeated three times using independently grown cultures.

In-gel Digestion and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The in-gel digestion of proteins for mass spectrometric characterization was performed as published previously (26). After the tryptic peptide mixture was dissolved with 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid, peptide mass analysis was performed using an AB4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). The mass spectra were externally calibrated with a peptide standard from Applied Biosystems. Based on NCBI human databases, the mass spectra were analyzed with a 50 ppm mass tolerance by GPS Explorer version 2.0.1 and Mascot version 1.9.

RNA Interference

For knockdown of DDB1, ROC1, CUL4A, CUL4B, and PrxIII, small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were used. The DDB1, ROC1, CUL4A, CUL4B, PrxIII, and negative control siRNA duplexes were purchased from GenePharma, and the oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: DDB1, 5′-CGUUGACAGUAAUGAACAATT-3′; ROC1, 5′-GAAGCGCUUUGAAGUGAAATT-3′; CUL4A, 5′-CCAUGUAAGUAAACGCUUATT-3′; CUL4B, 5′-CAAUCUCCUUGUUUCAGAATT-3′; PrxIII, 5′-GUGGCAGAGUGACUUAACUTT-3′; and negative control, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′.

Real-time PCR Assay

Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega) to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems). Human GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. The levels of specific mRNA were measured using 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primers were designed using the Primer 5.0 (Premier) program. The sequence-specific primers used in this assay are listed under supplemental Table 1S.

Antibodies and Immunological Procedures

Antibodies against the following proteins were purchased: anti-CUL4B (Sigma), anti-peroxiredoxin III (Abcam), anti-2-Cys peroxiredoxin (Abcam), anti-peroxiredoxin I, II, and IV (Abcam), anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-DDB1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-ROC1 (Abcam), anti-CUL4A (Abcam), anti-Ub (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-His tag (Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation analyses were performed as described previously (27, 28). The protein samples prepared from cell cultures were quantitated using the Bradford assay (24), subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 100 V using a standard transfer solution. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibody at a 1:1000 dilution, which was followed by incubation with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-conjugated horseradish peroxidase at a 1:1000 dilution. The proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using an ECL kit (Thermo). The degradation of PrxIII was assessed by cycloheximide (CHX) analysis. For CHX chase analysis, cells were harvested at specified time points after adding CHX (50 μg/ml) to the medium and then lysed in buffer, separated on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

In Vitro and In Vivo Ubiquitin Ligation Assays

The procedure for ubiquitin labeling was conducted as described in the literature (29). Briefly, to purify the substrate, His-tagged PrxIII was ectopically expressed in HEK293T cells, extracted in lysis buffer (Beyotime), and then purified using HisTrapTM FF crude columns (GE Healthcare). To purify the endogenous CUL4B ligases, CUL4B immunocomplexes were immunoprecipitated from untreated cells using a CUL4B antibody, immobilized on protein A + G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and then eluted by incubating with a molar excess of antigen peptide. For the in vitro PrxIII ubiquitination, the CUL4B immunocomplex was mixed with His-tagged PrxIII substrate, and this mixture was added to a ubiquitin ligation reaction (final volume of 50 μl, ubiquitinylation kit from Enzo Life Sciences) containing the following components: ubiquitinylation buffer, 20 units/ml inorganic pyrophosphatase solution, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm Mg-ATP, 100 mm E1, 2.5 μm E2 (hUbc5c), 1 μm PrxIII, and 2.5 μm bovine ubiquitin. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and this reaction was terminated by boiling for 5 min in an SDS sample buffer containing 0.1 m dithiothreitol. Next, the samples were resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel before immunoblotting with the anti-PrxIII antibody to examine ubiquitin ladder formation. In vivo ubiquitination assays of recombinant protein were performed as described previously (27, 30). HEK293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding His6-tagged PrxIII and siRNA for the CUL4B gene. Cell lysates were prepared, and PrxIII precipitates were isolated with protein A + G-agarose and His tag antibodies and then subjected to Western blotting with antibodies specific for Ub and PrxIII.

Apoptosis Assay and Determination of Cellular ROS by Flow Cytometry

Cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide using an Alexa Fluor 488-annexin V/dead cell apoptosis kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Apoptosis was analyzed by quantifying the annexin V-positive cell population by flow cytometry using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). To measure cellular ROS levels, the cells were incubated with 2′,7′-dichlorofluoresin-diacetate (DCFH-DA), in the dark for 15 min at 37 °C (31). After washing, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, which was performed using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using the FCSExpress V3 program (DeNovo Software).

RESULTS

Proteomic Analysis of miNeg and miCUL4B HEK293 Cells

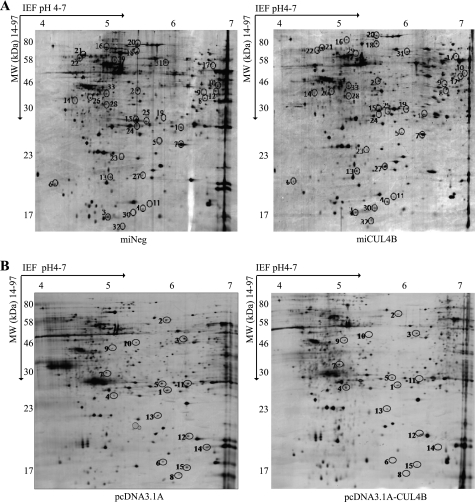

To identify novel substrates for CUL4B, we compared miCUL4B and miNeg HEK293 cells for changes in protein levels caused by CUL4B silencing. miCUL4B cells, which have reduced CUL4B expression due to CUL4B-specific RNAi, and the control miNeg cells were produced as described previously (13). Fig. 1A shows silver-stained two-dimensional gel electrophoresis IPG standard maps from one representative experiment with the two cell lines. Spot analysis using two-dimensional PDquest (Bio-Rad) detected 1879 ± 62 spots in miNeg cells (Fig. 1A, left) and 2005 ± 57 spots in miCUL4B cells (Fig. 1A, right). The expression of a protein is considered to have changed if the percentage volume of its spots on the gels shows a 2-fold or greater difference (p < 0.05). Thirty-three differentially expressed proteins between miCUL4B and miNeg HEK293 cells were excised from the two-dimensional electrophoresis gels, digested in gel, and applied to a sample template for the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Twenty-one protein spots were successfully identified with Mascot using peptide mass fingerprinting data. The protein names, NCBI accession numbers, Mascot score, theoretical Mr, and pI values, as well as the number of peptide matches and probability of incorrect assignment, are presented in Table 1. Of 21 proteins identified, 14 of them, including PrxIII, are up-regulated, whereas 7 proteins are down-regulated. According to their known and postulated functions, all 21 identified proteins were further classified into several categories based on oxidative stress, energy metabolism, transcription modulation, cytoskeleton, and signaling pathways (supplemental Table 2S).

FIGURE 1.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis electrophoretograms (A) of miNeg HEK293 cells and miCUL4B HEK293 cells (B) and pcDNA3.1 A and pcDNA3.1 A-CUL4B HEK293 cells. Cell lysates containing 450 μg of total protein were loaded for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis. The gels were silver stained and analyzed using PDQuest two-dimensional electrophoresis by Bio-Rad. Differentially expressed proteins are marked with numbers in the gel maps.

TABLE 1.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins between the miNeg HEK293 cells and miCUL4B HEK293 cells

| Spot no. | Protein description | Mr/pI | Matched peptides | Coverage (%) | NCBI accession No. | Mascot score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Up-regulated proteins in miCUL4B HEK293 cells | ||||||

| 1 | Triose-phosphate isomerase 1 | 26700/6.45 | 7/20 | 25 | 4507645 | 72 |

| 2 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit 2β | 36606/5.38 | 7/33 | 44 | 4503513 | 83 |

| 4 | Superoxide dismutase 1, soluble | 15941/5.70 | 6/36 | 85 | 4507149 | 151 |

| 5 | Peroxiredoxin III | 25854/6.00 | 6/17 | 29 | 32483377 | 272 |

| 8 | Cyclin H | 37779/6.73 | 5/17 | 21 | 4502623 | 63 |

| 11 | Non-metastatic cells 1, protein (NM23A) expressed in isoform b | 17217/5.83 | 9/27 | 31 | 4557797 | 84 |

| 13 | Glyoxalase I | 20818/5.24 | 11/31 | 26 | 5729842 | 75 |

| 14 | Tropomyosin 3 isoform 2 | 29127/4.75 | 7/65 | 33 | 24119203 | 96 |

| 19 | Proteasome α1 subunit isoform 2 | 29665/6.15 | 9/35 | 51 | 4506179 | 59 |

| 20 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 9B precursor | 73922/5.87 | 31/62 | 40 | 24234688 | 332 |

| 30 | Heat shock 27-kDa protein 3 | 16987/5.66 | 3/27 | 30 | 53688 | 57 |

| 31 | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | 57340/6.11 | 3/6 | 22 | 45439306 | 82 |

| 32 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone)1β subcomplex | 12082/5.47 | 2/19 | 30 | 4758778 | 61 |

| 33 | 2B28 protein | 35229/5.32 | 5/18 | 29 | 21361517 | 173 |

| B. Down-regulated proteins in miCUL4B HEK293 cells | ||||||

| 3 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A | 16917/5.08 | 4/28 | 47 | 4503545 | 174 |

| 16 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 5 (glucose-regulated protein, 78 kDa) | 72464/5.07 | 16/48 | 40 | 16507237 | 173 |

| 18 | Tripartite motif-containing 47 | 69600/6.03 | 6/15 | 15 | 54792146 | 57 |

| 25 | ATP binding protein associated with cell differentiation | 26581/5.61 | 4/24 | 19 | 18104959 | 75 |

| 26 | Annexin A5 | 36042/4.94 | 11/21 | 51 | 4502107 | 278 |

| 28 | Sulfotransferase family, member 1 | 33239/5.42 | 16/59 | 49 | 7657633 | 67 |

| 29 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K isoform b | 51136/5.39 | 14/37 | 19 | 14165435 | 79 |

In addition, we screened global protein expression changes caused by overexpression of CUL4B between HEK293 cells stably transfected with pcDNA3.1A (Fig. 1B, left) and pcDNA3.1A-CUL4B (Fig. 1B, right). The results indicate that 15 proteins were differentially expressed. Nine protein spots were identified successfully with mass spectrometry. The names of the proteins, their NCBI accession numbers, Mascot scores, theoretical Mr, and pI values, as well as the number of peptide matches and probability of incorrect assignment, are presented in Table 2. These proteins were also further classified into several categories (supplemental Table 3S).

TABLE 2.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins between the pcDNA3.1 A HEK293 cells and pcDNA3.1 A-CUL4B HEK293 cells

| Spot no. | Protein description | Mr/pI | Matched peptides | Sequencing coverage (100%) | NCBI accession No. | Mascot score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Up-regulated proteins in pcDNA3.1A-CUL4B HEK293 cells | ||||||

| 7 | F-actin capping protein α-1 subunit | 32966/5.45 | 8/19 | 49 | 5453597 | 167 |

| 9 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, subunit 2β, 36 kDa | 36607/5.38 | 9/19 | 54 | 4503513 | 268 |

| B. Down-regulated proteins in pcDNA3.1A-CUL4B HEK293 cells | ||||||

| 1 | Homebox prox1 | 28099/6.19 | 8/18 | 38 | 7706322 | 183 |

| 2 | Chaperonin containing TCP1, subunit 6A isoform a | 58212/6.23 | 3/9 | 30 | 4502643 | 87 |

| 3 | RuvB-like 1 | 50404/6.02 | 9/21 | 29 | 4506753 | 288 |

| 5 | Proteasome α1 subunit isoform | 29665/6.15 | 3/11 | 35 | 14506179 | 72 |

| 10 | Ras-GTPase-activating protein SH3-domain-binding protein | 52308/5.36 | 7/31 | 19 | 5031703 | 152 |

| 11 | Endoplasmic reticulum protein 29 isoform 1 precursor | 29071/6.77 | 3/11 | 39 | 5803013 | 81 |

| 13 | Peroxiredoxin III | 25854/6.00 | 6/25 | 21 | 32483377 | 67 |

CUL4B Is Essential for Proteasome-dependent Degradation of PrxIII

Among all the identified proteins, PrxIII is of particular interest because it was present in the lists of changed proteins following knockdown or overexpression of CUL4B. Thus, we sought to investigate whether CUL4B targets PrxIII for degradation.

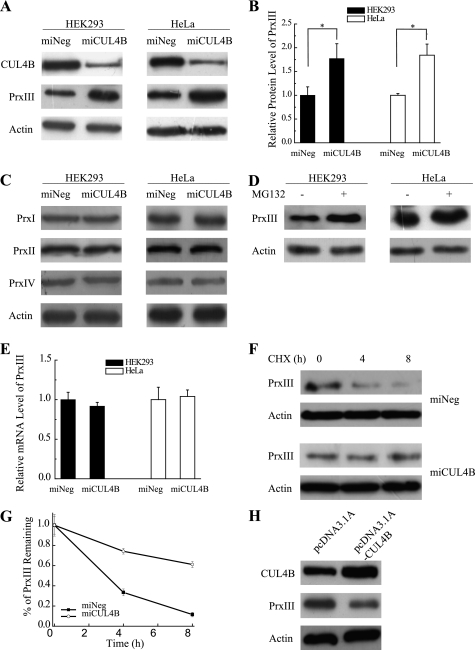

To verify the proteomic analysis result that the protein level of PrxIII is different between miCUL4B and miNeg HEK293 cells, we conducted an immunoblotting assay using whole cell extracts prepared from these cell lines. The results show a 2-fold increase of PrxIII in miCUL4B HEK293 cells compared with miNeg HEK293 cells (Fig. 2, A and B). The miCUL4B HeLa cells showed a similar trend in the accumulation of PrxIII (Fig. 2, A and B), whereas silencing of CUL4B did not cause any change in abundance in the other three 2-Cys Prx proteins (PrxI, PrxII, and PrxIV), as measured by immunoblotting assays (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Knockdown of CUL4B impairs PrxIII degradation. A, miNeg, miCUL4B HEK293 cells and HeLa cells were harvested. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. B, shown is the compiled data from three independent experiments of miNeg and miCUL4B of HEK293 cells (filled bars) and HeLa cells (open bars). The intensities of the gel bands were quantitated using the Quantity One program. The level of actin served as a loading control. Columns, mean; Bars, ±S.D.; *, p < 0.05. C, analysis of PrxI, PrxII, and PrxIV expressed in miNeg, miCUL4B HEK293 cells, and HeLa cells. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. D, HEK293 cells and HeLa cells treated with MG132 (10 μm) were harvested. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. E, the mRNA levels of PrxIII in HEK293 cells and HeLa cells were measured by real-time PCR. Compiled data were produced from three independent experiments of miNeg and miCUL4B of HEK293 (filled bars) and HeLa (open bars) cells. Columns, mean; Bars, ±S.D. F, a representative CHX chase analysis of PrxIII protein degradation (miNeg and miCUL4B) in HEK293 cells. Levels of proteins, at the indicated time points following addition of CHX (50 μg/ml) to cells, were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. G, quantitative graphs (mean ± S.D. of three experiments) are shown. H, HEK293 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 A and pcDNA3.1 A-CUL4B were harvested. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins.

Treatment of the cell lines with MG132 (10 μm), an inhibitor of 26 S proteasome, also resulted in an increased accumulation of PrxIII (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the enhanced accumulation of PrxIII results from the inhibition of proteasomal degradation. In addition, we performed real-time PCR to determine whether the enhanced PrxIII protein accumulation was due to increased PrxIII gene transcription. We observed no corresponding increase of PrxIII mRNA in CUL4B silenced human cells (Fig. 2E), suggesting that knockdown of CUL4B impaired PrxIII degradation.

To test this hypothesis, we preformed a CHX analysis and observed that CUL4B silencing resulted in a significant increase in the PrxIII half-life compared with that of control cells (Fig. 2, F and G). We next sought to investigate the effects of increased CUL4B expression on the levels of endogenous PrxIII. As expected, the immunoblotting assay revealed that transfection with the pcDNA3.1 A-CUL4B plasmid led to PrxIII decreases in the HEK293 cells (Fig. 2H). Taken together, these experiments confirm our findings from proteomics analysis, indicating that CUL4B participates in the proteasomal degradation of PrxIII.

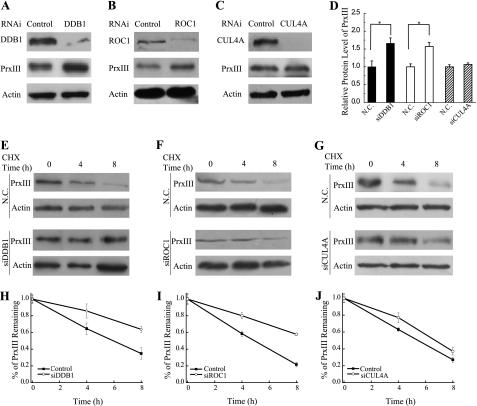

Integrity of DDB1-CUL4B-ROC1 Is Required for Degradation of PrxIII and This Degradation Is Independent of CUL4A

CUL4B provides a “scaffold” for the multisubunit E3 ligase by binding to the adaptor protein DDB1 and the RING finger protein ROC1 (2). To test whether the degradation of PrxIII involves DDB1-CUL4B-ROC1 E3 ligase, we analyzed the protein levels of PrxIII in DDB1- or ROC1-silenced cells. The PrxIII protein abundance was significantly increased in siDDB1- and siROC1-transfected cells compared with the negative control cells (Fig. 3, A, B, and D).

FIGURE 3.

PrxIII degradation is impaired in cells deficient for DDB1 or ROC1, independent of CUL4A. A–C, HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. D, quantization data from A–C from three independent experiments shown graphically. Columns, mean; Bars, ±S.D.; *, p < 0.05. E–G, a representative CHX chase analysis of PrxIII protein degradation in DDB1 knockdown, ROC1 knockdown, and CUL4A knockdown cells, respectively. The protein levels at the indicated time points after adding CHX to cells (at 50 μg/ml) were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. H–J, quantization data of E–G from three independent experiments shown graphically (bars, ±S.D.). N.C., negative control.

We also tested whether CUL4A participates in the degradation of PrxIII by measuring the level of PrxIII in cells in which CUL4A was silenced. Interestingly, the PrxIII protein levels were not affected by CUL4A knockdown, suggesting that PrxIII degradation is independent of CUL4A (Fig. 3, C and D).

To further assess the role of DDB1, ROC1, and CUL4A in the maintenance of PrxIII protein stability, we used CHX to block protein synthesis and then examined the half-life of PrxIII after transfection with either the negative control plasmid or a siRNA. As shown in Fig. 3, E–J, silencing of either DDB1 or ROC1 resulted in a significant increase in the half-life of PrxIII, whereas silencing of CUL4A showed no difference.

Together, these findings show that efficient PrxIII degradation depends on the integrity of DDB1-CUL4B-ROC1 E3 ligase. CUL4A, however, does not appear to be involved in the degradation of PrxIII.

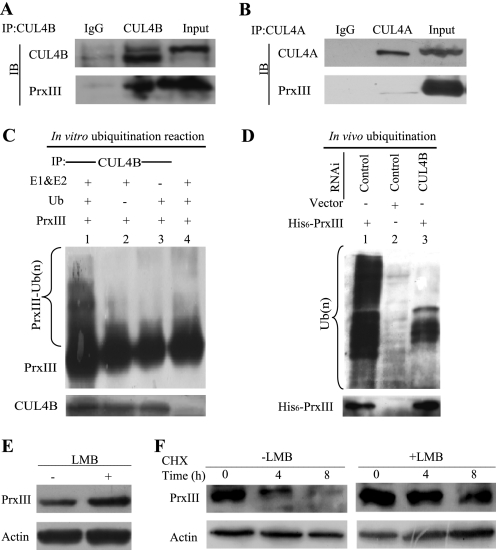

CUL4B-dependent Polyubiquitination of PrxIII in Vitro and in Vivo

Our data (Figs. 2 and 3) implicated CUL4B E3 ligase activities in PrxIII degradation and suggested that the PrxIII protein may undergo ubiquitination within the CUL4B E3 complex. Therefore, we next determined whether CUL4B or CUL4A interacts with PrxIII. We immunoprecipitated CUL4B and CUL4A complexes from HEK293 cells and found that PrxIII was present in anti-CUL4B immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3, C and G, PrxIII was not detected in anti-CUL4A immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

CUL4B promotes polyubiquitination of PrxIII in vitro and in vivo. A, PrxIII interacts with the CUL4B complex in HEK293 cells. B, no PrxIII was detected in anti-CUL4A immunoprecipitates. Whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the antibodies against the indicated proteins. Immunocomplexes were then subjected to immunoblotting (IB) using antibodies against the indicated proteins. C, in vitro ubiquitination of PrxIII by the CUL4B immunocomplex. For in vitro ubiquitination of PrxIII protein, a nickel column was used to purify His6-PrxIII from HEK293T cells, and the CUL4B immunocomplex and E3 were used as substrates, respectively. Assays were performed in 50-μl volume reactions containing each component, as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” The reaction was conducted at 37 °C for 60 min, and the analysis was performed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for PrxIII or CUL4B, as previously indicated. D, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-His6 antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-Ub antibody to detect ubiquitylated PrxIII protein. E, LMB stabilizes PrxIII. HEK293 cells were transfected with negative control plasmids. After 24 h, the cells were either untreated or exposed to LMB for 6 h, and protein extracts were prepared. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. F, CHX chase analysis of PrxIII protein degradation in LMB-treated and control cells. Protein levels at the indicated time points after adding CHX (at 50 μg/ml) to cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins.

We next performed an in vitro ubiquitination assay to directly examine whether CUL4B ligase could promote PrxIII ubiquitination in vitro. To accomplish this, we transfected a pcDNA3.1/myc-His A-PrxIII plasmid into HEK293T cells, purified His6-PrxIII, immunoprecipitated CUL4B ligase complexes as a source of E3 ligase, and then assayed the ability of CUL4B to polyubiquitinate purified PrxIII in the presence of E1, E2, and ubiquitin. Our results demonstrate that incubation of the CUL4B immunocomplexes with purified PrxIII in vitro resulted in the formation of polyubiquitinated forms of PrxIII, which were readily detectable as a smear of higher molecular weight bands (Fig. 4C, lane 1). Omission of the ubiquitin, E1, and E2, or CUL4B immunocomplexes abolished the PrxIII polyubiquitin ladder (Fig. 4C, lanes 2–4).

Furthermore, we tested PrxIII ubiquitination by CUL4B ubiquitin ligase in vivo. HEK293T cells were transfected with the His6-PrxIII expression construct together with RNA interference (control or siCUL4B). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-His6 antibodies and immunoblotted with an anti-Ub antibody to detect ubiquitinated PrxIII proteins. As expected, the PrxIII immunoblotting analysis confirmed that His6-PrxIII was immunoprecipitated and that higher molecular weight bands conjugated with Ub were indeed polyubiquitinated forms of His6-PrxIII (Fig. 4D, lane 1). Moreover, PrxIII ubiquitination decreased significantly in cells without His6-PrxIII expression or in cells with CUL4B knockdown (Fig. 4D, lanes 2 and 3).

Endogenous CUL4B is primarily detected in the nucleus (13), whereas PrxIII is largely found within mitochondria (19). Therefore, we tested how PrxIII degradation is affected by the presence and absence of the nuclear export inhibitor leptomycin B (LMB). As shown in Fig. 4, E and F, LMB treatment led to the accumulation and increased half-life of PrxIII. These findings suggest that PrxIII degradation is dependent on nuclear export and, therefore, likely occurs in cytoplasm.

These results collectively demonstrate that CUL4B ubiquitinates PrxIII in vitro and that the efficient PrxIII ubiquitination in vivo requires CUL4B. The findings also suggest that nuclear export may play a role in PrxIII degradation.

CUL4B Silencing Leads to ROS Decreases and Resistance to Hypoxia- and H2O2-induced ROS Formation and Apoptosis

Last, we investigated the contribution made by the CUL4B/PrxIII regulatory pathway to the ROS status and the resistance to hypoxia- and H2O2-induced apoptosis. ROS have been implicated in the induction of cell proliferation under a variety of circumstances. Silencing of CUL4B results in cell proliferation defects (13). Cells expressing mutant CUL4B allele were severely selected against in CUL4B heterozygous females (14). However, a study of stable PrxIII overexpression in thymoma cell systems also indicated an inhibitory role of ROS in cell proliferation (32). Moreover, exposure to hypoxia or H2O2 is known to increase cellular ROS and can eventually cause apoptosis (33, 34). PrxIII-transfected cells show resistance to hypoxia- and H2O2-induced ROS formation and apoptosis (32), and CUL1 ubiquitin ligase (SCFFBW7) governs cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 (35). Therefore, we predicted that impaired degradation of PrxIII caused by CUL4B knockdown would have similar effects.

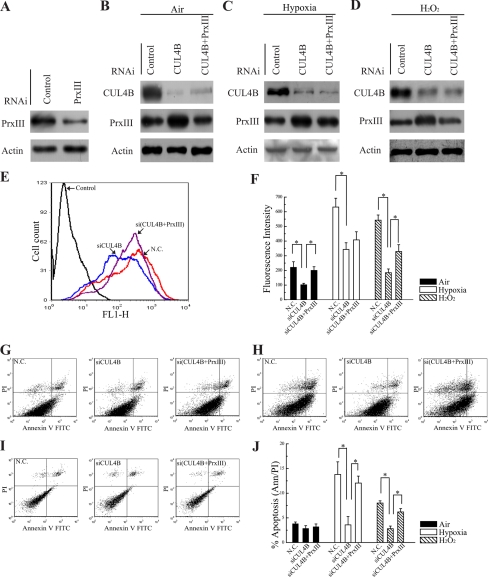

To this end, HEK293 cells were first treated with control siRNA and siRNA specific for PrxIII (Fig. 5A). Next, cells treated with siRNAs specific for CUL4B, CUL4B + PrxIII (to offset the effect of PrxIII accumulation caused by silencing of CUL4B), or with control siRNAs under air, hypoxia (24 h in 1% O2), and H2O2 (24 h in 100 μm H2O2) inductions (Fig. 5, B–D) were prelabeled with DCFH-DA (a free radical-recognizing dye) and then analyzed using flow cytometry. Importantly, the silencing of CUL4B led to a significant decrease in ROS production (Fig. 5E, blue and red lines). To determine whether the difference was due to the impaired degradation of PrxIII, ROS production was measured in si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells. As shown in Fig. 5E, the decrease in ROS production caused by siCUL4B (blue line) was offset in si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells (purple line), demonstrating that the reduction in ROS production of siCUL4B cells was indeed mediated by the up-regulation of PrxIII. Quantitative summary of three replicated experiments indicated that ROS production was reduced 2-fold in CUL4B-silencing cells compared with negative control cells, whereas in si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells, ROS production was restored to the level in negative control cells (Fig. 5F, filled bars). Indeed, the cellular ROS levels were significantly induced by hypoxia and H2O2 (Fig. 5F). The hypoxia induction of ROS level in siCUL4B cells was only about half of that in control cells. However, the ROS levels in si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells were not significantly different when compared with siCUL4B cells (Fig. 5F, open bars), presumably due to the already high levels of ROS production in these cells. ROS induction by H2O2 was also measured. As expected, the results showed that ROS levels were 3-fold lower in siCUL4B cells compared with control cells. Silencing of CUL4B and PrxIII increased ROS levels to ∼53% that observed in control RNAi-treated cells (Fig. 5F, hatched bars).

FIGURE 5.

Silencing of CUL4B decreases the level of ROS and confers resistance to hypoxia- and H2O2-induced ROS formation and apoptosis. A–D, HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Equivalent amounts (30 μg) of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. A representative Western blot is shown in B (air), C (1% O2), and D (H2O2, 100 μm H2O2) inductions. E, HEK293 cells transfected with control, siCUL4B, and si(CUL4B + PrxIII) plasmids were labeled with DCF-DA and analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative histogram (red, blue, and purple lines indicate ROS production in N.C., siCUL4B and si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells, respectively) is shown. F, DCF-DA fluorescence measurements of cellular ROS levels in the N.C., siCUL4B and si(CUL4B + PrxIII) HEK293 cells grown in either air (filled bars), 1% O2 for 24 h (open bars), or exposed to 100 μm H2O2 for 24 h (hatched bars). Columns, mean; Bars, ±S.D.; *, p < 0.05. Compiled data were produced from three independent experiments. G–I, apoptosis measured by annexin V/propidium iodide staining and FACScan. Typical dot plots of data are shown for N.C., siCUL4B, and si(CUL4B + PrxIII)_ cells grown in air, 1% O2 for 24 h, or exposed to 100 μm H2O2 for 24 h, respectively. J, compiled percentage from three independent experiments of apoptotic N.C., siCUL4B, and si(CUL4B + PrxIII) HEK293 cells grown in air (filled bars), 1% O2 for 24 h (open bars) or exposed to 100 μm H2O2 for 24 h (hatched bars). Columns, mean; Bars, ±S.D.; *, p < 0.05. N.C., negative control.

Next, experiments were performed to monitor the resistance to hypoxia- and H2O2-induced apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5, G and J (filled bars), there was no significant change in the percentages of spontaneous apoptosis. After incubation in 1% O2 for 24 h, 3.58 ± 0.67% of siCUL4B HEK293 cells were apoptotic, in comparison to 13.79 ± 2.56% in cells transfected with negative control vectors (Fig. 5, H and J, open bars). In contrast, the apoptosis ratio of si(CUL4B + PrxIII) cells was returned to 12.05 ± 1.41% (Fig. 5, H and J, open bars). We next asked whether the CUL4B/PrxIII regulatory pathway was responsible for resistance to the increase in H2O2-induced apoptosis. As expected, loss of CUL4B resulted in 2.80 ± 0.53% apoptotic cells relative to 8.14 ± 0.45% in control cells and a concomitant 6.25 ± 0.67% apoptotic cells induced by CUL4B + PrxIII silencing (Fig. 5, I and J, hatched bars). These results support the conclusion that CUL4B silencing cells are more resistant to the increase in hypoxia- and H2O2-induced apoptosis than control cells. Together, these data suggest that impaired degradation of PrxIII caused by CUL4B knockdown results in decreased levels of cellular ROS and renders resistance to ROS formation and apoptosis caused by hypoxia and H2O2 treatments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified PrxIII as a novel substrate of CUL4B ubiquitin ligase. We found that CUL4B silencing resulted in the accumulation of PrxIII and that CUL4B mediates the polyubiquitination of PrxIII in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the adaptor protein DDB1 and the RING protein ROC1 are required for the degradation of PrxIII. However, we discovered that CUL4A, the paralogue of CUL4B, is not involved in PrxIII degradation. Moreover, we provided evidence showing that the accumulation of PrxIII in CUL4B-silencing cells caused a striking decrease in ROS production and imparted resistant to apoptosis after hypoxia and H2O2 treatments. As a whole, these findings indicate that PrxIII is a specific target protein of CUL4B ubiquitin ligase.

CUL4 exists as a single gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Xenopus laevis, Canenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Arabidopsis thaliana. CUL4 mutations in these organisms have been demonstrated to cause a wide range of impairments at the cellular and organismal levels, including defects in chromatin remodeling (36–39). However, CUL4 diverged into two closely related genes, CUL4A and CUL4B, in mammalian cells and other higher organisms. Human CUL4A and CUL4B share ∼80% protein sequence homology, with CUL4B containing an extended N terminus (39). The tissue-specific expression pattern also differs between CUL4A and CUL4B (40). These early findings indicate that mammalian CUL4A and CUL4B are not likely to be entirely redundant.

Several groups have reported great phenotypic variations in Cul4a knock-out mice from early embryonic lethality associated with the deletion of exon 1 (Cul4aΔ1/Δ1) (41) to lacking remarkable abnormalities with the deletion of exons 17 to 19 (Cul4aΔ17–19/Δ17–19) (42). Thus far, no germ line mutations in human CUL4A have been reported. However, overexpression of CUL4A has been found in breast and hepatocellular cancers (43, 44). Although there are no reports of Cul4b mutant mice, genetic studies have shown that mutations in the CUL4B gene cause XLMR (14–16). In addition, CUL4A was shown to target p53, p21, p27, and CHK1 for degradation (8, 27, 45–47), whereas knockdown of CUL4B has no effect on the levels of these proteins (13). These findings imply that CUL4B complexes may operate distinctly from those containing CUL4A.

CUL4B has been identified as part of a dioxin receptor (AhR) immunocomplex and in the assembly of a specific ubiquitin ligase complex that targets the estrogen receptor α for degradation (17). CUL4B has also been reported to mediate ubiquitination of several proteins, such as CDT1, cyclin E, and histone H3 and H4 (6, 8, 48); however, all of these can also be ubiquitinated by CUL4A ubiquitin ligase. Here, we report the identification and characterization of a novel and specific substrate of CUL4B ubiquitin ligase.

XLMR accounts for a large proportion of inherited mental retardation. Patients lacking CUL4B exhibit abnormalities in multiple systems, most notably in central neural system function, skeletal development, and hematopoiesis (14, 15). Although the genetic link between CUL4B and XLMR has been identified, the underlying physiology remains poorly understood. Investigations of a possible functional link between a lack of CUL4B expression and the accumulation of PrxIII with regard to the pathogenesis of XLMR merits further study.

The elevated levels of ROS are conventionally known to be toxic to cells and can lead to apoptosis. Although PrxIII is widely believed to function as a scavenger of H2O2 to protect against ROS-induced damage, other functions have been proposed, such as the regulation of cellular signal transduction (49, 50). We have shown that CUL4B-silenced cells are able to scavenge excess ROS and confer resistance to hypoxia- and H2O2-induced apoptosis. ROS are generated in the mitochondria during hypoxia (51) and this may explain why mitochondrial-localized PrxIII offers more resistance to hypoxia-induced apoptosis than to H2O2 treatment, in which the effects may also be cytoplasmic (32).

Although the majority of research has focused on the damaging effects of ROS, emerging evidence now suggests that high ROS levels can actually promote proliferation and self-renewal of certain kinds of stem cells (52, 53). For example, a high ROS state enhances proliferation and self-renewal hematopoietic stem cells (53). More recently, it has been found that proliferative, self-renewing multipotent neural progenitors maintain a high ROS status and are highly responsive to ROS stimulation (52). Correspondingly, a decrease in normal cellular ROS levels had negative impacts on the self-renewal and differentiation potential that is required for normal neural stem cell functions (52).

We previously reported that the silencing of CUL4B results in a reduced cellular proliferation (13). Here, we observed that the accumulation of PrxIII caused by CUL4B knockdown leads to a considerable decrease in ROS production. In support of these findings, diminished levels of cellular ROS, mediated by the stable overexpression of PrxIII, also interfere with cell proliferation in the thymoma cell system (32). In light of these data, the silencing of CUL4B is expected to cause the accumulation of PrxIII and, thus, enhance ROS scavenging capacity. It is possible that decreased ROS levels as a consequence of CUL4B deficiency might not be high enough to sustain normal neural stem cell proliferation and impair neurogenesis in CUL4B-mutant patients.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PrxIII is a specific substrate for CUL4B ubiquitin ligase. When CUL4B is silenced, PrxIII may be elevated to inhibit the generation of ROS and may, therefore, interfere with cell proliferation and other normal cellular functions. It would be interesting to further investigate the effects of CUL4B knockdown and the resulting stability of PrxIII in animal models and/or stem cells. However, a large number of specific substrates for CUL4B ligase might be involved in brain development and neural function. Thus, investigating additional target substrates of CUL4B and their functional roles in brain development are necessary to offer insights into the physiological functions of CUL4B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yongxin Zou for providing miNeg and miCUL4B HEK293 cell lines. We also thank Dr. Molin Wang and Dr. Yan Wang for providing insightful discussion throughout this study.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30830065, 30800614, 81070223, 60974117, and 30901987, National Basic Research Program of China Grants 2007CB512001 and 2011CB966201, Science Foundation of Shandong Province Grant ZR2010HM038, Science Foundation for the Excellent Youth Scholars of Ministry of Education of China Grant 200804221067, and the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3.

- DDB1

- damaged DNA binding protein 1

- CUL4B

- Cullin 4B

- PrxIII

- peroxiredoxin III

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- XLMR

- X-linked mental retardation

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- LMB

- leptomycin B

- DCFH-DA

- 2′,7′-dichlorofluoresin-diacetate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weissman A. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petroski M. D., Deshaies R. J. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zheng N., Schulman B. A., Song L., Miller J. J., Jeffrey P. D., Wang P., Chu C., Koepp D. M., Elledge S. J., Pagano M., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Harper J. W., Pavletich N. P. (2002) Nature 416, 703–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stebbins C. E., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Pavletich N. P. (1999) Science 284, 455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu L., Wei Y., Reboul J., Vaglio P., Shin T. H., Vidal M., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W. (2003) Nature 425, 316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hu J., McCall C. M., Ohta T., Xiong Y. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1003–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chew E. H., Hagen T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17032–17040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higa L. A., Yang X., Zheng J., Banks D., Wu M., Ghosh P., Sun H., Zhang H. (2006) Cell Cycle 5, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. He Y. J., McCall C. M., Hu J., Zeng Y., Xiong Y. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 2949–2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higa L. A., Wu M., Ye T., Kobayashi R., Sun H., Zhang H. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Angers S., Li T., Yi X., MacCoss M. J., Moon R. T., Zheng N. (2006) Nature 443, 590–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin J., Arias E. E., Chen J., Harper J. W., Walter J. C. (2006) Mol. Cell 23, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zou Y., Mi J., Cui J., Lu D., Zhang X., Guo C., Gao G., Liu Q., Chen B., Shao C., Gong Y. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33320–33332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zou Y., Liu Q., Chen B., Zhang X., Guo C., Zhou H., Li J., Gao G., Guo Y., Yan C., Wei J., Shao C., Gong Y. (2007) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 561–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tarpey P. S., Raymond F. L., O'Meara S., Edkins S., Teague J., Butler A., Dicks E., Stevens C., Tofts C., Avis T., Barthorpe S., Buck G., Cole J., Gray K., Halliday K., Harrison R., Hills K., Jenkinson A., Jones D., Menzies A., Mironenko T., Perry J., Raine K., Richardson D., Shepherd R., Small A., Varian J., West S., Widaa S., Mallya U., Moon J., Luo Y., Holder S., Smithson S. F., Hurst J. A., Clayton-Smith J., Kerr B., Boyle J., Shaw M., Vandeleur L., Rodriguez J., Slaugh R., Easton D. F., Wooster R., Bobrow M., Srivastava A. K., Stevenson R. E., Schwartz C. E., Turner G., Gecz J., Futreal P. A., Stratton M. R., Partington M. (2007) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 345–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tarpey P. S., Smith R., Pleasance E., Whibley A., Edkins S., Hardy C., O'Meara S., Latimer C., Dicks E., Menzies A., Stephens P., Blow M., Greenman C., Xue Y., Tyler-Smith C., Thompson D., Gray K., Andrews J., Barthorpe S., Buck G., Cole J., Dunmore R., Jones D., Maddison M., Mironenko T., Turner R., Turrell K., Varian J., West S., Widaa S., Wray P., Teague J., Butler A., Jenkinson A., Jia M., Richardson D., Shepherd R., Wooster R., Tejada M. I., Martinez F., Carvill G., Goliath R., de Brouwer A. P., van Bokhoven H., Van Esch H., Chelly J., Raynaud M., Ropers H. H., Abidi F. E., Srivastava A. K., Cox J., Luo Y., Mallya U., Moon J., Parnau J., Mohammed S., Tolmie J. L., Shoubridge C., Corbett M., Gardner A., Haan E., Rujirabanjerd S., Shaw M., Vandeleur L., Fullston T., Easton D. F., Boyle J., Partington M., Hackett A., Field M., Skinner C., Stevenson R. E., Bobrow M., Turner G., Schwartz C. E., Gecz J., Raymond F. L., Futreal P. A., Stratton M. R. (2009) Nat. Genet. 41, 535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohtake F., Baba A., Takada I., Okada M., Iwasaki K., Miki H., Takahashi S., Kouzmenko A., Nohara K., Chiba T., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kato S. (2007) Nature 446, 562–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang T. S., Cho C. S., Park S., Yu S., Kang S. W., Rhee S. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41975–41984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wood Z. A., Schröder E., Robin Harris J., Poole L. B. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci 28, 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tu S. C. (2001) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3, 881–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Monteiro G., Horta B. B., Pimenta D. C., Augusto O., Netto L. E. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 4886–4891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rhee S. G., Chae H. Z., Kim K. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 1543–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lehtonen S. T., Markkanen P. M., Peltoniemi M., Kang S. W., Kinnula V. L. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 288, L997–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zor T., Selinger Z. (1996) Anal. Biochem. 236, 302–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kong L., Yu X. P., Bai X. H., Zhang W. F., Zhang Y., Zhao W. M., Jia J. H., Tang W., Zhou Y. B., Liu C. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26381–26391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shevchenko A., Tomas H., Havlis J., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 2856–2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leung-Pineda V., Huh J., Piwnica-Worms H. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 2630–2637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li Y., Gazdoiu S., Pan Z. Q., Fuchs S. Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11074–11080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wei W., Ayad N. G., Wan Y., Zhang G. J., Kirschner M. W., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2004) Nature 428, 194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nasu J., Murakami K., Miyagawa S., Yamashita R., Ichimura T., Wakita T., Hotta H., Miyamura T., Suzuki T., Satoh T., Shoji I. (2010) J. Cell. Biochem. 111, 676–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mauro C., Crescenzi E., De Mattia R., Pacifico F., Mellone S., Salzano S., de Luca C., D'Adamio L., Palumbo G., Formisano S., Vito P., Leonardi A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2631–2638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nonn L., Berggren M., Powis G. (2003) Mol. Cancer Res. 1, 682–689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chandel N. S., McClintock D. S., Feliciano C. E., Wood T. M., Melendez J. A., Rodriguez A. M., Schumacker P. T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25130–25138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu X., Kim C. N., Yang J., Jemmerson R., Wang X. (1996) Cell 86, 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Inuzuka H., Shaik S., Onoyama I., Gao D., Tseng A., Maser R. S., Zhai B., Wan L., Gutierrez A., Lau A. W., Xiao Y., Christie A. L., Aster J., Settleman J., Gygi S. P., Kung A. L., Look T., Nakayama K. I., DePinho R. A., Wei W. (2011) Nature 471, 104–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jia S., Kobayashi R., Grewal S. I. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1007–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhong W., Feng H., Santiago F. E., Kipreos E. T. (2003) Nature 423, 885–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bernhardt A., Lechner E., Hano P., Schade V., Dieterle M., Anders M., Dubin M. J., Benvenuto G., Bowler C., Genschik P., Hellmann H. (2006) Plant J. 47, 591–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jackson S., Xiong Y. (2009) Trends Biochem. Sci 34, 562–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hori T., Osaka F., Chiba T., Miyamoto C., Okabayashi K., Shimbara N., Kato S., Tanaka K. (1999) Oncogene 18, 6829–6834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li B., Ruiz J. C., Chun K. T. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4997–5005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu L., Lee S., Zhang J., Peters S. B., Hannah J., Zhang Y., Yin Y., Koff A., Ma L., Zhou P. (2009) Mol. Cell 34, 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen L. C., Manjeshwar S., Lu Y., Moore D., Ljung B. M., Kuo W. L., Dairkee S. H., Wernick M., Collins C., Smith H. S. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 3677–3683 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schindl M., Gnant M., Schoppmann S. F., Horvat R., Birner P. (2007) Anticancer Res 27, 949–952 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim Y., Starostina N. G., Kipreos E. T. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 2507–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miranda-Carboni G. A., Krum S. A., Yee K., Nava M., Deng Q. E., Pervin S., Collado-Hidalgo A., Galic Z., Zack J. A., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. I., Lane T. F. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 3121–3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nishitani H., Shiomi Y., Iida H., Michishita M., Takami T., Tsurimoto T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29045–29052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang H., Zhai L., Xu J., Joo H. Y., Jackson S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Xiong Y., Zhang Y. (2006) Mol. Cell 22, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muller F. L., Lustgarten M. S., Jang Y., Richardson A., Van Remmen H. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 477–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Baier M., Dietz K. J. (1997) Plant J. 12, 179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chandel N. S., Maltepe E., Goldwasser E., Mathieu C. E., Simon M. C., Schumacker P. T. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11715–11720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Le Belle J. E., Orozco N. M., Paucar A. A., Saxe J. P., Mottahedeh J., Pyle A. D., Wu H., Kornblum H. I. (2011) Cell Stem Cell 8, 59–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jang Y. Y., Sharkis S. J. (2007) Blood 110, 3056–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.