Increased numbers of innate lymphoid cells in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Abstract

Results of experimental and genetic studies have highlighted the role of the IL-23/IL-17 axis in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IL-23–driven inflammation has been primarily linked to Th17 cells; however, we have recently identified a novel population of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) in mice that produces IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ in response to IL-23 and mediates innate colitis. The relevance of ILC populations in human health and disease is currently poorly understood. In this study, we have analyzed the role of IL-23–responsive ILCs in the human intestine in control and IBD patients. Our results show increased expression of the Th17-associated cytokine genes IL17A and IL17F among intestinal CD3− cells in IBD. IL17A and IL17F expression is restricted to CD56− ILCs, whereas IL-23 induces IL22 and IL26 in the CD56+ ILC compartment. Furthermore, we observed a significant and selective increase in CD127+CD56− ILCs in the inflamed intestine in Crohn’s disease (CD) patients but not in ulcerative colitis patients. These results indicate that IL-23–responsive ILCs are present in the human intestine and that intestinal inflammation in CD is associated with the selective accumulation of a phenotypically distinct ILC population characterized by inflammatory cytokine expression. ILCs may contribute to intestinal inflammation through cytokine production, lymphocyte recruitment, and organization of the inflammatory tissue and may represent a novel tissue-specific target for subtypes of IBD.

IL-23 plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of experimental colitis in mice (Hue et al., 2006; Yen et al., 2006; Elson et al., 2007; Izcue et al., 2008). Compartmentalization of the IL-23/IL-17 pathway has been observed in these models with IL-23 being the key cytokine driving intestinal inflammation, whereas systemic disease is dependent on IL-12 (Uhlig et al., 2006). Results from human studies have converged with the identification in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of multiple susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms in many genes encoding for proteins involved in the IL-23/IL-17 pathway, including IL23R, IL12B, STAT3, JAK2, and CCR6 (Duerr et al., 2006; Barrett et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2008; Franke et al., 2008). In addition, Th17 signature cytokines (Wilson et al., 2007) are elevated in the intestine and serum of patients with IBD, and Th17 cells with an activated phenotype are present in the colon and blood of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD; Fujino et al., 2003; Andoh et al., 2005; Di Sabatino et al., 2009; Kleinschek et al., 2009). IL-23 plays an important role in sustaining Th17 responses (Cua et al., 2003). In addition to its effects on T cells, Takatori et al. (2009) have shown that IL-23 also acts on innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) to induce IL-17 and IL-22 production. These ILCs share a similar phenotype to lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells, which are involved in the organogenesis of secondary lymphoid organs through TNF and lymphotoxin-β–mediated induction of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and MAdCAM-1 on mesenchymal cells (Mebius et al., 1997; Cupedo et al., 2004; Eberl et al., 2004). LTi and related ILC populations are both dependent on the transcription factor RAR-related orphan receptor C (RORC), which is also required for Th17 cell development. Whereas LTi cells are active in the fetus, IL-22–producing ILC populations are thought to provide innate antimicrobial defense in the adult (Satoh-Takayama et al., 2008; Luci et al., 2009; Sanos et al., 2009). Recently, we have described an IL-23–responsive ILC population that mediates innate colitis through an IL-17– and IFN-γ–dependent mechanism, indicating an important functional role for ILCs in the intestinal inflammatory response (Buonocore et al., 2010).

IL-23–responsive ILC populations have also been identified in human mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, such as intestinal Peyer’s patches and tonsils. Cella et al. (2009) described CD3−CD56+NKp44+ cells, termed NK22 cells, that produce IL-22 but not IL-17 in response to IL-23. Like Th17 cells, NK22 cells also express the transcription factor RORC. Although originally thought to represent a subset of NK cells, recent studies suggest that NK22 cells are developmentally and functionally related to LTi cells (Crellin et al., 2010; Satoh-Takayama et al., 2010). The role of human innate lymphoid sources of IL-17 and IL-22 in the pathogenesis of immunological disorders has not been investigated. In this study, we describe the accumulation of IL-23–responsive ILCs in the inflamed intestine of patients with CD. Human ILCs may contribute to intestinal inflammation through the production of IL-17 and the recruitment of other inflammatory cells and therefore may represent a novel tissue-specific therapeutic target for patients with IBD.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Th17 signature genes are expressed in intestinal non-T cells in the absence of intestinal inflammation and are overexpressed in IBD

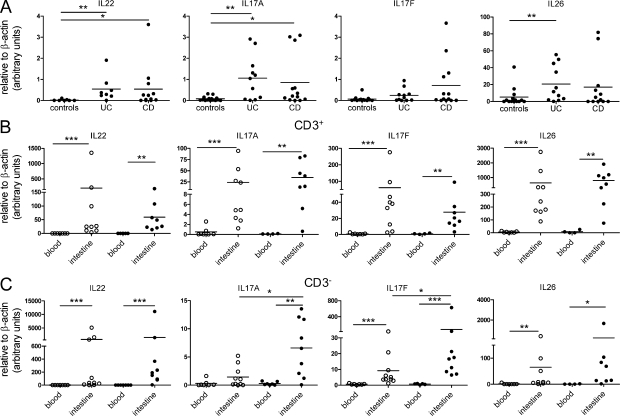

In this study, we aimed to analyze the contribution of adaptive and innate sources of Th17 signature cytokines to chronic intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD. We confirmed the overexpression of Th17 signature cytokine genes in the inflamed intestinal mucosa in our cohort of patients with IBD, either ulcerative colitis (UC) or CD, compared with the nonaffected colon of patients undergoing colectomy for colorectal cancer as noninflammatory controls (Fig. 1 A). To evaluate the contribution of innate and adaptive sources of Th17 signature cytokines in the human systemic and intestinal immune response in the absence and presence of IBD, we compared T cell and non-T cell expression of Th17 genes in the peripheral blood (PB) versus the lamina propria (LP) of IBD patients and controls (Fig. 1, B and C). We found preferential expression of IL22, IL17A, IL17F, and IL26 in CD3+ cells isolated from the intestine compared with the blood of both control and IBD patients (Fig. 1 B). In line with these results, Kobayashi et al. (2008) described higher expression of IL-17 in LP CD4+ cells compared with the PB CD4+ population. Compartmentalization of Th17 gene expression was not restricted to T cells as we also found increased expression of IL22, IL17F, and IL26 in LP CD3− cells with nondetectable or very low expression among PB CD3− cells (Fig. 1 C) in both IBD and control individuals. IL17A expression was also increased in LP CD3− cells compared with PB CD3− in IBD patients. This increase was specific to intestinal inflammation because no significant difference was observed in noninflamed controls. Other Th17 genes such as IL21, IL23R, RORC, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) were also expressed in both the intestinal T and non-T cell compartments, with very low or nondetectable expression in blood leukocytes (Fig. S1, A and B). These results confirm our hypothesis of a specific role for the IL-23 axis in the intestinal immune response and show that both T and non-T cells expressing Th17-related genes are present in the human intestine.

Figure 1.

Th17 signature genes are expressed in intestinal CD3− cells and overexpressed in IBD. (A) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of Th17 signature cytokines in intestinal tissue homogenates from control, UC, and CD patients. (B and C) mRNA expression of Th17-related genes in CD3+ cells (B) and CD3− cells (C) isolated from blood and intestine of control (open circles) and IBD (closed circles) patients. In some experiments, B cells have been excluded (CD3−CD19− cells). (A–C) The horizontal bars represent the mean of each of the groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Interestingly, we found no significant differences between patients and controls in expression of Th17 genes in LP CD3+ cells (Fig. 1 B and Fig. S1 A), although absolute numbers of intestinal Th17 cells are increased in IBD, as suggested by Kleinschek et al. (2009). Strikingly, significantly higher expression of IL17A and IL17F was observed in LP CD3− cells isolated from patients with IBD (Fig. 1 C) compared with controls. No significant difference was observed for IL22, IL26, RORC, AHR, and IL23R expression (Fig. 1 C and Fig. S1 B). IL21 expression was very low or undetectable in most PB and LP CD3− cells from IBD patients (Fig. S1 B). These findings suggest that innate sources of IL-17A and IL-17F might contribute to intestinal inflammation in IBD.

ILCs are a source of IL-17 and accumulate in the intestine of patients with CD

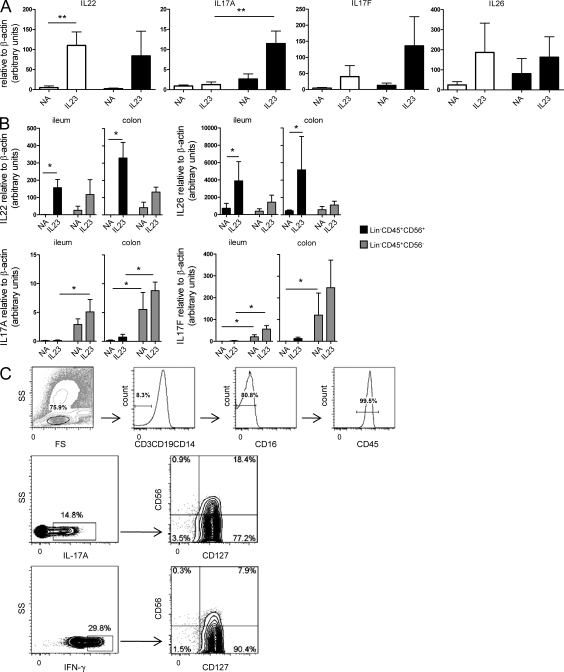

To determine whether intestinal non-T cells are responsive to IL-23 and whether the innate response is altered in IBD, sorted LP CD3− cells from patients and controls were cultured overnight with or without IL-23, and Th17 gene expression was evaluated (Fig. 2 A). IL22 was induced by IL-23 stimulation in non-T cells isolated from control colon, confirming the presence of IL-23–responsive innate cells in the human intestine. Induction of IL26 was not observed after IL-23 stimulation in LP CD3− cells from either controls or IBD patients. However, IL26 transcripts were very low in some cultures, leading to a large variation in expression levels. Interestingly, IL17A in LP CD3− cells after IL-23 stimulation was significantly higher in cells isolated from patients with IBD compared with controls. All together, these data suggest that an IL-23–dependent source of IL-17 is present in the CD3− compartment in the inflamed colon of patients with IBD but not in controls.

Figure 2.

ILCs are a source of IL-17 in IBD. (A) mRNA expression of IL22, IL17A, IL17F, and IL26 in CD3− cells from control (open bars; n = 9 for IL22, IL17A, and IL17F and n = 7 for IL26) and IBD colon (closed bars; n = 4) after overnight culture in complete media with no addition (NA) and in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-23. In some experiments, B cells have been excluded (CD3−CD19− cells). **, P = 0.006. (B) mRNA expression of IL22, IL26, IL17A, and IL17F in Lin−CD45+CD56+ and Lin−CD45+CD56− cells from the ileum (n = 4) and colon (n = 4) of patients with CD after overnight stimulation in complete media with no addition (NA) and in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-23. *, P = 0.029. (A and B) Mean ± standard error of the mean is represented. (C) Intracellular staining for IL-17A and IFN-γ after PMA/ionomycin stimulation in LPMCs isolated from the ileum of a patient with CD (representative of two experiments). LPMCs were gated on the lymphocytic gate (FSC/SSC), were CD3−CD19−CD14−, CD16−, CD45+, and costained with CD56 and CD127.

In humans, CD3−CD127+ ILCs can be further subdivided based on expression of the NK marker CD56 (Crellin et al., 2010). Both populations can be isolated from human adult tonsils and share the expression of NKp44, NKp46, CD161, c-Kit, and RORC. In vitro expanded CD127+CD56− and CD127+CD56+ cells showed a similar cytokine profile, including production of IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ. In vitro analysis suggests a precursor-product relationship with CD56 expression induced upon activation. However, the relative distribution and function of these ILC populations in the human intestine in health and disease have not been examined.

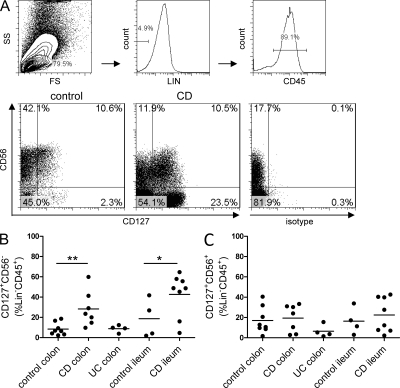

To further characterize the intestinal IL-23–responsive non-T cell source of Th17 cytokines in the inflamed intestine of patients with IBD, we sorted CD3−CD19−CD14−CD16−(Lin−) CD45+CD56+ cells and Lin−CD45+CD56− cells from the ileum and colon of patients with CD and cultured them with IL-23. IL22 and IL26 were induced by IL-23 in the CD56+ population. In contrast, IL17A and IL17F were preferentially expressed in the Lin−CD45+CD56− population analyzed directly ex vivo, and levels were not increased upon addition of IL-23 (Fig. 2 B). Expression of IFNγ was detected among ileal as well as colonic Lin−CD45+CD56+ and Lin−CD45+CD56− cells from patients with CD (Fig. S2). Further analysis of the phenotype of IL-17A– and IFN-γ–producing cells in the Lin− compartment by intracellular FACS staining showed that these cells were primarily CD127+CD56− (77% and 90%, respectively; Fig. 2 C). Analysis of the frequency of intestinal Lin−CD45+CD127+CD56− cells and Lin−CD45+CD127+CD56+ (termed CD56− and CD56+ ILCs) in patients with CD, UC, and controls showed that although both populations were present at similar frequencies in the uninflamed colon and ileum of control individuals, there was a marked increase specifically in CD56− ILCs in the inflamed ileum and colon of CD patients. Interestingly, no difference in the frequency of CD56− and CD56+ ILCs was observed in the colon of UC patients versus controls, indicating that accumulation of CD56− ILCs might be a specific feature of CD (Fig. 3, A–C). Consistent with low IL22 expression, only a small percentage of CD56− ILCs that accumulated in CD expressed NKp44, suggesting that they represent a distinct population from IL-22–producing NK22 cells, which expressed NKp44 and represented a quarter of CD56+ ILCs (Fig. S3 A). Both intestinal CD56− and CD56+ ILCs also expressed the chemokine receptor CCR6 (Fig. S3 B). It has been reported that CCL20 and β-defensins, which are known CCR6 ligands, are both increased in the inflamed intestine of patients with IBD (Wehkamp et al., 2002; Kwon et al., 2003; Kaser et al., 2004). These results raise the possibility that a CCR6-mediated mechanism might be responsible for the recruitment of ILCs to the intestine in IBD.

Figure 3.

CD56− ILCs accumulate in the intestine in CD. (A) Representative staining of CD127+CD56− and CD127+CD56+ ILCs from control and CD intestine. LPMCs were gated on the lymphocytic gate in the FSC/SSC plot, the Lin− and CD45+ population. (B and C) Percentage of CD127+CD56− (B) and CD127+CD56+ ILCs (C) in the Lin−CD45+ population, using the gates shown in A, in the colon of control, CD, and UC patients and in the ileum of control and CD patients. (B and C) The horizontal bars represent the mean of each of the groups. *, P = 0.048; **, P = 0.004.

In this study, an IL-23–dependent innate lymphoid source of IL-17A and IL-17F, which shares features of human LTi cells, has been identified in the intestine of patients with CD. The differential accumulation of IL-17A– and IL-17F–producing ILCs in the inflamed CD intestine is very similar to the accumulation of IL-17A–secreting ILCs that mediate innate colitis in mice (Buonocore et al., 2010). Further understanding of the factors that selectively promote IL-17–producing ILCs at the expense of tissue-protective IL-22–producing populations during intestinal inflammation may provide novel insights into immune pathology in the intestine. It is notable that increases in NKp44−NKp46+CD56+CD3− cells capable of secreting IFN-g in response to IL-23 have been observed in CD patients, emphasizing a more pathogenic phenotype amongst ILC populations (Takayama et al., 2010). These results also raise important questions about the developmental relationship between CD56− and CD56+ ILC populations in vivo.

CD56− ILCs may contribute to chronic intestinal inflammation not only through the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17A and IL-17F but potentially through induction of adhesion molecules and recruitment of other lymphocytes. Indeed, increased numbers of isolated lymphoid follicles are typically found in the colon of patients with IBD. This study opens the way to further work on the functional role of distinct ILC populations in intestinal inflammation and identifies a potential tissue-specific target for the treatment of patients with IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

All patients and controls were recruited from the gastroenterology unit and the colorectal surgery department at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford. The diagnosis of IBD was confirmed by established clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and histological criteria. Blood samples and gut specimens were obtained from patients with IBD undergoing surgery for severe disease, chronically active disease, or complications of disease. Blood samples and gut specimens from macroscopically healthy areas were collected from colorectal cancer patients as noninflammatory controls. Biopsies were collected from inflamed areas of the colon and small bowel of patients with IBD, undergoing endoscopy for assessment of disease activity, extension or surveillance, and the noninflamed intestine of healthy subjects. Ethical approval was obtained from the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee (reference number 07/Q1605/35), and informed written consent was given by all study participants.

Isolation of cells.

LP mononuclear cells (LPMCs) were isolated using a modified version of the protocol described by Bull and Bookman (1977). In brief, the mucosa was dissected, cut in pieces <25 mm2, and washed in 1 mM DTT solution at room temperature for 15 min to remove adherent mucus. Specimens were washed three times in 0.75 mM EDTA solution at 37°C for 45 min to detach the epithelial crypts and then digested overnight in 0.1 mg/ml collagenase D solution (Roche). Cells were then centrifuged for 30 min in a Percoll gradient and collected at the 40–60% interface. All solutions used were supplemented with antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin, 40 µg/ml gentamicin, and 0.025 µg/ml Amphotericin B).

PB was diluted in an equal volume of PBS and centrifuged over a Ficoll-Hypaque layer at 2,000 rpm. Cells were collected at the Ficoll–dilute plasma interface. LPMCs were isolated from biopsies (up to 10 per patient) using a combined mechanical (GentleMACS; Miltenyi Biotech) and enzymatic digestion process.

Cell sorting.

CD3+ and CD3− cells were sorted either by magnetic cell sorting with positive selection of CD3+ (CD3 Micro Beads; Miltenyi Biotech) or by FACS using a MoFlow (Dako). CD3−, CD3−CD19−, Lin−CD45+CD56+, and Lin−CD45+CD56− cells were FACS sorted. The following antibodies were used: anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-CD56 (BD), anti-CD14, anti-CD16 (eBioscience), and anti-CD45 (BioLegend).

Cultures.

Cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% FCS, antibiotics, and l-glutamine with or without recombinant human IL-23 (R&D Systems) at 10 ng/ml concentration.

Quantitative PCR.

RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) and cDNA synthesized using Superscript III and oligo (dT) primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed with ACTB-, IL17A-, IL17F-, IL22-, IL21-, IFNγ–, IL23R-, RORC-, and AHR-specific primers (QuantiTect Primer Assays; QIAGEN) and Platinum SYBR green qPCR super mix (Invitrogen). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for ACTB and IL26 were also used in some experiments (Applied Biosystems). cDNA samples were assayed in triplicate using the Chromo4 detection system (GMI), and gene expression levels for each individual sample were normalized to β-actin. Mean relative gene expression was determined and expressed as 2−ΔCT (ΔCT = CTgene − CTβ-actin) × 10,000.

FACS staining.

Cells were preincubated in 2% normal rat serum. The following antibodies were used for flow cytometry: anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-CD56 (BD), anti-CD14, anti-CD16, anti-CD127, anti–IL-17, anti–IFN-γ, anti-NKp44, anti-CCR6 (eBioscience), and anti-CD45 (BioLegend). For the intracellular staining, cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of brefeldin A for 4 h and fixed/permeabilized (eBioscience). Analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star), and gates were set using relevant IgG isotype controls.

Statistics.

The nonparametric, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was performed in Prism software (GraphPad Software) in all cases. Mean ± standard error of the mean is represented on bar charts.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows that Th17 signature genes are expressed in intestinal CD3− cells and overexpressed in IBD. Fig. S2 shows that IFN-γ is expressed in both intestinal Lin−CD45+CD56+ and Lin−CD45+CD56− cells. Fig. S3 shows phenotyping of intestinal CD56− and CD56+ ILCs. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20101712/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Derek P. Jewell for his support and advice, Dr. Holm H. Uhlig, Dr. Hergen Spits, and Dr. Tom Cupedo for critically reading the manuscript, and the patients and their families for agreeing to take part in this study.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (F. Powrie and A. Geremia), the Lee-Placito Medical Fund (A. Geremia), and the Broad Medical Research Program of the Broad Foundation (C.V. Arancibia-Cárcamo).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- AHR

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CD

- Crohn’s disease

- IBD

- inflammatory bowel disease

- ILC

- innate lymphoid cell

- LP

- lamina propria

- LPMC

- LP mononuclear cell

- LTi

- lymphoid tissue inducer

- mRNA

- messenger RNA

- PB

- peripheral blood

- RORC

- RAR-related orphan receptor C

- UC

- ulcerative colitis

References

- Andoh A., Zhang Z., Inatomi O., Fujino S., Deguchi Y., Araki Y., Tsujikawa T., Kitoh K., Kim-Mitsuyama S., Takayanagi A., et al. 2005. Interleukin-22, a member of the IL-10 subfamily, induces inflammatory responses in colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 129:969–984 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J.C., Hansoul S., Nicolae D.L., Cho J.H., Duerr R.H., Rioux J.D., Brant S.R., Silverberg M.S., Taylor K.D., Barmada M.M., et al. 2008. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat. Genet. 40:955–962 10.1038/ng.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull D.M., Bookman M.A. 1977. Isolation and functional characterization of human intestinal mucosal lymphoid cells. J. Clin. Invest. 59:966–974 10.1172/JCI108719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore S., Ahern P.P., Uhlig H.H., Ivanov I.I., Littman D.R., Maloy K.J., Powrie F. 2010. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 464:1371–1375 10.1038/nature08949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M., Fuchs A., Vermi W., Facchetti F., Otero K., Lennerz J.K., Doherty J.M., Mills J.C., Colonna M. 2009. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 457:722–725 10.1038/nature07537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crellin N.K., Trifari S., Kaplan C.D., Cupedo T., Spits H. 2010. Human NKp44+IL-22+ cells and LTi-like cells constitute a stable RORC+ lineage distinct from conventional natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 207:281–290 10.1084/jem.20091509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua D.J., Sherlock J., Chen Y., Murphy C.A., Joyce B., Seymour B., Lucian L., To W., Kwan S., Churakova T., et al. 2003. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 421:744–748 10.1038/nature01355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupedo T., Jansen W., Kraal G., Mebius R.E. 2004. Induction of secondary and tertiary lymphoid structures in the skin. Immunity. 21:655–667 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sabatino A., Rovedatti L., Kaur R., Spencer J.P., Brown J.T., Morisset V.D., Biancheri P., Leakey N.A., Wilde J.I., Scott L., et al. 2009. Targeting gut T cell Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels inhibits T cell cytokine production and T-box transcription factor T-bet in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Immunol. 183:3454–3462 10.4049/jimmunol.0802887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr R.H., Taylor K.D., Brant S.R., Rioux J.D., Silverberg M.S., Daly M.J., Steinhart A.H., Abraham C., Regueiro M., Griffiths A., et al. 2006. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 314:1461–1463 10.1126/science.1135245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Marmon S., Sunshine M.J., Rennert P.D., Choi Y., Littman D.R. 2004. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat. Immunol. 5:64–73 10.1038/ni1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson C.O., Cong Y., Weaver C.T., Schoeb T.R., McClanahan T.K., Fick R.B., Kastelein R.A. 2007. Monoclonal anti-interleukin 23 reverses active colitis in a T cell-mediated model in mice. Gastroenterology. 132:2359–2370 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S.A., Tremelling M., Anderson C.A., Gwilliam R., Bumpstead S., Prescott N.J., Nimmo E.R., Massey D., Berzuini C., Johnson C., et al. 2008. Genetic determinants of ulcerative colitis include the ECM1 locus and five loci implicated in Crohn’s disease. Nat. Genet. 40:710–712 10.1038/ng.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke A., Balschun T., Karlsen T.H., Hedderich J., May S., Lu T., Schuldt D., Nikolaus S., Rosenstiel P., Krawczak M., Schreiber S. 2008. Replication of signals from recent studies of Crohn’s disease identifies previously unknown disease loci for ulcerative colitis. Nat. Genet. 40:713–715 10.1038/ng.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino S., Andoh A., Bamba S., Ogawa A., Hata K., Araki Y., Bamba T., Fujiyama Y. 2003. Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 52:65–70 10.1136/gut.52.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hue S., Ahern P., Buonocore S., Kullberg M.C., Cua D.J., McKenzie B.S., Powrie F., Maloy K.J. 2006. Interleukin-23 drives innate and T cell–mediated intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 203:2473–2483 10.1084/jem.20061099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izcue A., Hue S., Buonocore S., Arancibia-Cárcamo C.V., Ahern P.P., Iwakura Y., Maloy K.J., Powrie F. 2008. Interleukin-23 restrains regulatory T cell activity to drive T cell-dependent colitis. Immunity. 28:559–570 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A., Ludwiczek O., Holzmann S., Moschen A.R., Weiss G., Enrich B., Graziadei I., Dunzendorfer S., Wiedermann C.J., Mürzl E., et al. 2004. Increased expression of CCL20 in human inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Immunol. 24:74–85 10.1023/B:JOCI.0000018066.46279.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschek M.A., Boniface K., Sadekova S., Grein J., Murphy E.E., Turner S.P., Raskin L., Desai B., Faubion W.A., de Waal Malefyt R., et al. 2009. Circulating and gut-resident human Th17 cells express CD161 and promote intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 206:525–534 10.1084/jem.20081712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Okamoto S., Hisamatsu T., Kamada N., Chinen H., Saito R., Kitazume M.T., Nakazawa A., Sugita A., Koganei K., et al. 2008. IL23 differentially regulates the Th1/Th17 balance in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 57:1682–1689 10.1136/gut.2007.135053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J.H., Keates S., Simeonidis S., Grall F., Libermann T.A., Keates A.C. 2003. ESE-1, an enterocyte-specific Ets transcription factor, regulates MIP-3alpha gene expression in Caco-2 human colonic epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:875–884 10.1074/jbc.M208241200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luci C., Reynders A., Ivanov I.I., Cognet C., Chiche L., Chasson L., Hardwigsen J., Anguiano E., Banchereau J., Chaussabel D., et al. 2009. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat. Immunol. 10:75–82 10.1038/ni.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R.E., Rennert P., Weissman I.L. 1997. Developing lymph nodes collect CD4+CD3- LTbeta+ cells that can differentiate to APC, NK cells, and follicular cells but not T or B cells. Immunity. 7:493–504 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80371-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanos S.L., Bui V.L., Mortha A., Oberle K., Heners C., Johner C., Diefenbach A. 2009. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat. Immunol. 10:83–91 10.1038/ni.1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Takayama N., Vosshenrich C.A.J., Lesjean-Pottier S., Sawa S., Lochner M., Rattis F., Mention J.J., Thiam K., Cerf-Bensussan N., Mandelboim O., et al. 2008. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 29:958–970 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Takayama N., Lesjean-Pottier S., Vieira P., Sawa S., Eberl G., Vosshenrich C.A., Di Santo J.P. 2010. IL-7 and IL-15 independently program the differentiation of intestinal CD3−NKp46+ cell subsets from Id2-dependent precursors. J. Exp. Med. 207:273–280 10.1084/jem.20092029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatori H., Kanno Y., Watford W.T., Tato C.M., Weiss G., Ivanov I.I., Littman D.R., O’Shea J.J. 2009. Lymphoid tissue inducer–like cells are an innate source of IL-17 and IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 206:35–41 10.1084/jem.20072713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama T., Kamada N., Chinen H., Okamoto S., Kitazume M.T., Chang J., Matuzaki Y., Suzuki S., Sugita A., Koganei K., et al. 2010. Imbalance of NKp44(+)NKp46(-) and NKp44(-)NKp46(+) natural killer cells in the intestinal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease. 139:882–892 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig H.H., McKenzie B.S., Hue S., Thompson C., Joyce-Shaikh B., Stepankova R., Robinson N., Buonocore S., Tlaskalova-Hogenova H., Cua D.J., Powrie F. 2006. Differential activity of IL-12 and IL-23 in mucosal and systemic innate immune pathology. Immunity. 25:309–318 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehkamp J., Fellermann K., Herrlinger K.R., Baxmann S., Schmidt K., Schwind B., Duchrow M., Wohlschläger C., Feller A.C., Stange E.F. 2002. Human beta-defensin 2 but not beta-defensin 1 is expressed preferentially in colonic mucosa of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14:745–752 10.1097/00042737-200207000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N.J., Boniface K., Chan J.R., McKenzie B.S., Blumenschein W.M., Mattson J.D., Basham B., Smith K., Chen T., Morel F., et al. 2007. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8:950–957 10.1038/ni1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen D., Cheung J., Scheerens H., Poulet F., McClanahan T., McKenzie B., Kleinschek M.A., Owyang A., Mattson J., Blumenschein W., et al. 2006. IL-23 is essential for T cell-mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. J. Clin. Invest. 116:1310–1316 10.1172/JCI21404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]