Abstract

Objective

To develop a definition of competence in family medicine sufficient to guide a review of Certification examinations by the Board of Examiners of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Design

Delphi analysis of responses to a 4-question postal survey.

Setting

Canadian family practice.

Participants

A total of 302 family physicians who have served as examiners for the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s Certification examination.

Methods

A survey comprising 4 short-answer questions was mailed to the 302 participating family physicians asking them to list elements that define competence in family medicine among newly certified family physicians beginning independent practice. Two expert groups used a modified Delphi consensus process to analyze responses and generate 2 basic components of this definition of competence: first, the problems that a newly practising family physician should be competent to handle; second, the qualities, behaviour, and skills that characterize competence at the start of independent practice.

Main findings

Response rate was 54%; total number of elements among all responses was 5077, for an average 31 per respondent. Of the elements, 2676 were topics or clinical situations to be dealt with; the other 2401 were skills, behaviour patterns, or qualities, without reference to a specific clinical problem. The expert groups identified 6 essential skills, the phases of the clinical encounter, and 99 priority topics as the descriptors used by the respondents. More than 20% of respondents cited 30 of the topics.

Conclusion

Family physicians define the domain of competence in family medicine in terms of 6 essential skills, the phases of the clinical encounter, and priority topics. This survey represents the first level of definition of evaluation objectives in family medicine. Definition of the interactions among these elements will permit these objectives to become detailed enough to effectively guide assessment.

Résumé

Objectif

Élaborer une définition de la compétence en médecine familiale devant servir de guide pour réviser les examens de certification du Bureau des examinateurs du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada.

Type d’étude

Analyse Delphi des réponses à une enquête postale comprenant 4 questions.

Contexte

La pratique de la médecine familiale au Canada.

Participants

Un total de 302 médecins de famille ayant déjà agi comme examinateurs à l’examen de certification du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada.

Méthodes

Une enquête comportant 4 questions à réponses courtes a été postée aux 302 médecins de famille participants, leur demandant d’énumérer les éléments qui définissent la compétence en médecine familiale pour un médecin de famille nouvellement diplômé qui débute une pratique indépendante. Deux groupes experts ont utilisé une modification d’une méthode de consensus de type Delphi pour analyser le réponses et pour élaborer 2 composantes de base de cette définition de la compétence; premièrement, les problèmes qu’un médecin de famille en début de pratique devrait être en mesure de régler; deuxièmement, les qualités, le comportement et les habiletés qui caractérisent la compétence au début d’une pratique indépendante.

Principales observations

Le taux de réponses était de 54 %; le nombre total des éléments pour l’ensemble des réponses était de 5077, pour une moyenne de 31 par répondant. Parmi ces éléments, 2676 étaient des sujets ou des situations cliniques devant être pris en charge; les 2401 autres sujets étaient des habiletés, des modèles de comportement ou des qualités, non reliés à un problème clinique particulier. Le groupe d’experts a identifié 6 habiletés essentielles, les phases de l’expérience clinique et 99 sujets prioritaires d’après les descripteurs utilisés par les répondants. Plus de 20 % des répondants ont cité 30 des sujets.

Conclusion

Selon les médecins de famille, le domaine de la compétence en médecine familiale correspond à 6 habiletés essentielles, aux phases de l’expérience clinique et à des sujets prioritaires. Cette enquête représente une première étape dans la définition des objectifs de l’évaluation en médecine familiale. La définition des interactions entre ces éléments devrait permettre à ces objectifs de devenir suffisamment détaillés pour servir de guide efficace lors de l’évaluation.

In this article we present a definition of the basic components of the domain of competence in family medicine. It is expressed in terms of the problems that are dealt with during the practice of family medicine and in terms of the skills that are necessary to deal with these problems in a competent manner. This definition, once completed, will be the basis of a revised assessment used for Certification by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), so particular emphasis has been placed on the problems and skills most indicative of competence. The process was free of all constraints that are commonly imposed by predetermined examination formats or test instruments; these will be selected later to specifically assess the competencies as defined, rather than the other way around.

Professional competence

Kane,1 as he discussed the assessment of professional competence, defined professional practice as a “complex and intellectually demanding activity that is not easy to define precisely or evaluate accurately … though it looks like it should be easy.” He defined 2 major components to professional competence: it is limited to an area of practice and a competent professional can “handle the encounters or situations that arise in this area of practice.” He underlined the importance of defining the area of practice of any professional whenever we wish to discuss the notion of competence. Competence is very task specific; one can be very competent in some areas or for certain tasks and totally incompetent for others.

Can competence in a single profession or domain be defined in terms of certain generic skills, which can be observed across a series of similar tasks? Van der Vleuten2 has reviewed the literature in medicine and concluded that no distinct traits have been well-defined and there is no consensus on a taxonomy of clinical competence. For this reason clinical competence cannot yet be characterized as an aggregate of distinct latent attributes or traits. He stated that this should not be surprising, as “the notion of inherent and robust traits has been similarly challenged and abandoned in psychology some time ago.” Components of competence show great variability across even apparently similar tasks within a single profession. Any definition of competence must recognize the effect of the interaction between a particular skill and the particular situation to which it is being applied.

Epstein and Hundert,3 in an extensive review of the literature, build on several previous definitions of competence in medicine and define it as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served.” This definition has 7 components, but the definition of what is a competent performance in each component is still defined only to the level of “habitual and judicious.” It does clarify some of the skills and attitudes that make up competence, but the definition still lacks much detail and is insufficient for direct assessment. Epstein and Hundert derived their definition largely from 4 slightly more comprehensive frameworks of competence in medicine that are currently in use or have been promoted as models for medical education in North America: the 4 principles of family medicine of the CFPC4; Educating Future Physicians for Ontario5; CanMEDS 20056; and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency framework.7 There are both considerable differences and similarities among these 4 frameworks as well as others. However, they all have insufficient detail in the definition of competence at an operational level to truly direct assessment of competence. Albanese and colleagues8 have recently reviewed this state of affairs, and suggest 5 characteristics that any definition of competence should have in order to usefully direct the assessment of that competence. A competency should do the following:

Focus on the performance of the end product or goal of instruction.

Reflect expectations that apply what is learned in the immediate instructional program.

Be expressed in a measurable behaviour.

Use a standard for judging competence that is not dependent on the performance of other learners.

Inform learners, as well as other stakeholders, of what is expected of them.

Defining competency in family medicine

In 1998 the Board of Examiners of the CFPC observed that no definition of competence in family medicine existed that was sufficient to clearly direct the assessment of competence for the purposes of Certification. Members of the Board of Examiners therefore decided to develop an adequate definition to guide future changes in the Certification process. Job analysis is a time-honoured technique for determining what competencies are required for a particular job, and one approach to gathering the necessary information is to ask those already active and skilled for the job in question—in this case, practising family physicians. The definition of competence so obtained would be grounded in the experience of practising family physicians dealing with their patients in daily practice. As such it follows the Coan (versus Cnidian) tradition of the practice of medicine, a tradition that seems to be particularly appropriate for family medicine.9 This approach is also compatible with the situational model of competence suggested by Klass10 as most appropriate for assessing physician competence over the long term. This model is patient- and encounter-centred, is authentic and practical, and leads more naturally to effective assessment.10

This report deals with the first part of this exercise, namely overall definition of competence in family medicine in terms of the problems to be dealt with, as recommended by Kane,1 and of the skills most useful to dealing with these problems in a competent fashion. The second part of the exercise has used this primary information over the past 10 years for the further definition of problem-specific competencies, as recommended by Van der Vleuten2 and Albanese et al.8 These detailed interactions between the problems and the skills, or the operational competency-based evaluation objectives, have been developed and will be reported elsewhere.

METHODS

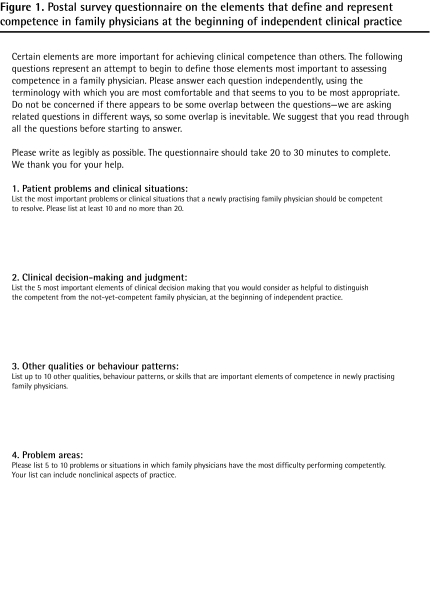

Postal survey

A postal survey of 4 questions requiring write-in answers (Figure 1) was sent to 302 practising family physicians in Canada, randomly selected from the approximately 800 College members who had been recently involved as examiners in the Certification examination of the CFPC. No demographic data were collected on the responders, but as examiners they were chosen to represent all regions of the country, came from academic and nonacademic settings, lived in both large and small communities, and had a range of ages and years of practice experience among them; there were also representatives from both sexes. The survey and analysis were done from 1998 to 2001. Respondents were asked to generate 2 types of answers: first, the problems and situations that a newly practising family physician should be competent to deal with; second, the qualities, behaviour, and skills that are generally characteristic of competence for this same point in practice.

Figure 1.

Postal survey questionnaire on the elements that define and represent competence in family physicians at the beginning of independent clinical practice

Interventions

Clinical competence is a complex issue and is not well-defined by quantitative data. Qualitative approaches, such as the Delphi process and consensus methods, have been recommended for such situations.11 Expert groups of 6 to 8 family physicians and 1 educational consultant analyzed the responses to the survey and used a modified Delphi consensus process to derive an initial definition of competence based on the priority topics to be dealt with and the skills (or dimensions of competence) most essential to dealing with these topics. There were multiple iterations until consensus was achieved for the items under discussion. All members of the expert groups had experience in assessing competence in family medicine, and represent the Canadian context as far as region, sex, language, community type, and experience are concerned.

Every element of the survey responses was classified as a “topic” answer (the problems and situations) or a “nontopic” answer (the qualities, behaviour, and skills). The first expert group, which was the CFPC Board of Examiners at the time, concentrated on identifying the themes or categories that were used by the respondents to define the dimensions of competence in family medicine at the start of independent practice. The starting point was their own experiences plus the nontopic elements from a convenience sample of 20 responses to the questionnaire. After several iterations, working with the responses from the survey as well as their own ideas and criteria, they proposed a final list of themes or categories. The nontopic elements of all the survey responses were then coded to these themes, and frequencies were calculated.

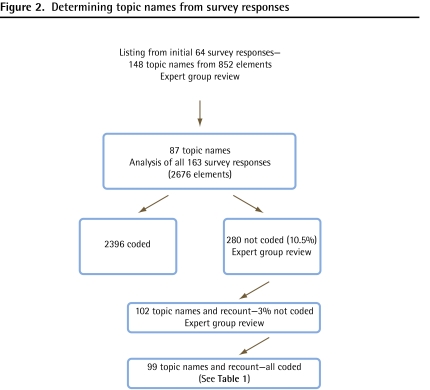

The second expert group was made of members who were selected for their particular expertise and experience in assessment, representing a cross section of family physicians. This group concentrated on the topic elements of the survey responses, identifying synonyms or duplications and proposing names for the topics. They started with all the topic names generated from the responses in the 64 questionnaires that had been received at the time of the first discussion, produced a revised name list, then coded all the survey responses, identifying those that did not code to the revised name list. The process was repeated until all the topic-element responses were coded to the topic name list (Figure 2). Frequencies of topic name citation were then calculated for all the survey responses.

Figure 2.

Determining topic names from survey responses

RESULTS

Survey participation

Response rate was 54% (163 responses). The total number of elements in the answers to the questions in all responses was 5077, an average of 31 per responder. The maximum number of elements expected per responder was 35 to 45. Of the elements, 2676 were topics—that is, the names of clinical problems or situations to be dealt with. The other 2401 were skills, behaviour, or qualities used to define competence without reference to a specific clinical problem.

Priority topics

Serial analysis and coding of the 2676 names of the clinical problems or situations resulted in a final list of 99 topics deemed important in determining competence to practise family medicine (Table 1 and Figure 2). The number 99 was not predetermined; it resulted entirely from the analytic process. All of the elements coded to 1 of these topics in the final iteration. The expert groups maintained, as much as possible, the terminology of the responders themselves. No standardized taxonomy was applied to the topics: the types of terms used can be seen in the topic list. Grouping of slightly dissimilar responses under more general topic names was minimal, and occurred only at the end of the process for problems that were cited only once or twice in the whole survey. Citation rates of topics varied from 87% (depression, anxiety) to 1% (dysuria and others) of all replies. The distribution of the frequencies of citation was markedly skewed, with some topics cited much more often than others. Twenty topics were cited in more than 30% of the replies, and 50 topics were cited by at least 10% of respondents.

Table 1.

Priority topics for the assessment of competence in family medicine

| TOPICS | RATE OF CITATION, % | TOPICS | RATE OF CITATION, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 87 | Behavioural problems | 10 |

| Anxiety | 87 | Allergy | 10 |

| Substance abuse | 60 | Multiple medical problems | 9 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 52 | Dizziness | 9 |

| Diabetes | 51 | Counseling | 9 |

| Hypertension | 50 | Earache | 9 |

| Pregnancy | 48 | Grief | 8 |

| Headache | 43 | Thyroid | 8 |

| Periodic health examination or screening | 42 | Stroke | 8 |

| Palliative care | 40 | Vaginitis | 7 |

| Family issues | 37 | Insomnia | 7 |

| Abdominal pain | 36 | Infections | 7 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 35 | Anemia | 6 |

| Difficult patient | 35 | Immunization | 6 |

| Domestic violence | 33 | Advanced cardiac life support | 6 |

| Asthma | 33 | Gastrointestinal bleeding | 5 |

| Chest pain | 32 | Obesity | 5 |

| Dementia | 32 | Lacerations | 5 |

| Low back pain | 32 | Eating disorder | 5 |

| Chronic disease | 29 | Antibiotics | 5 |

| Elderly | 29 | Stress | 4 |

| Contraception | 28 | Prostate | 4 |

| Sex | 28 | Fracture | 4 |

| Menopause | 27 | Newborn | 4 |

| Joint disorder | 26 | Immigrant issues | 4 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 24 | Deep venous thrombosis | 4 |

| Well-baby care | 24 | Hepatitis | 3 |

| Schizophrenia | 23 | Atrial fibrillation | 3 |

| Skin disorder | 23 | Parkinsonism | 3 |

| Disability | 20 | Learning | 3 |

| Personality disorder | 19 | Seizure | 3 |

| Fatigue | 18 | Infertility | 3 |

| Lifestyle | 18 | Loss of weight | 2 |

| Urinary tract infection | 16 | Mental competency | 2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16 | Osteoporosis | 2 |

| Trauma | 16 | Loss of consciousness | 2 |

| Cancer | 16 | Red eye | 2 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 15 | Croup | 2 |

| Fever | 15 | Poisoning | 2 |

| Smoking cessation | 15 | Meningitis | 2 |

| Bad news | 14 | Travel medicine | 2 |

| Violent or aggressive patient | 14 | Dehydration | 1 |

| Suicide | 14 | Diarrhea | 1 |

| Breast lump | 14 | Neck pain | 1 |

| Dyspepsia | 13 | Crisis | 1 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 13 | Dysuria | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 13 | Rape or sexual assault | 1 |

| In children | 13 | Gender-specific issues | 1 |

| Cough | 12 | Epistaxis | 1 |

| Somatization | 12 |

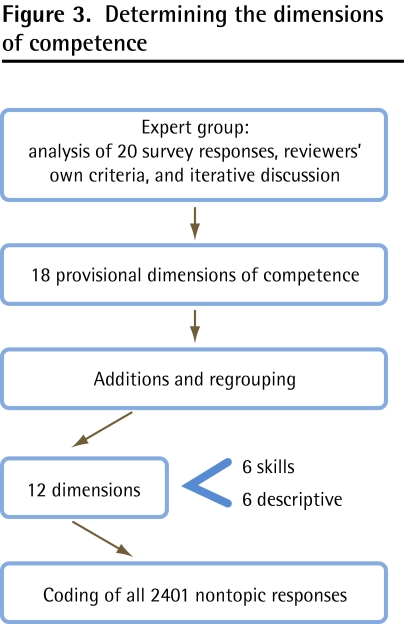

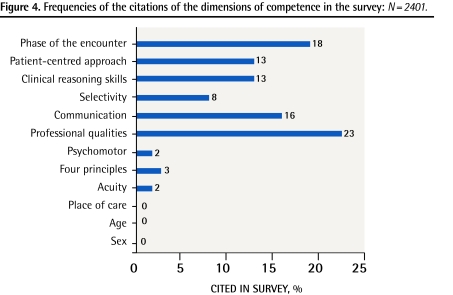

Dimensions of competence

Twelve categories or dimensions of competence were proposed as descriptors by the expert groups (Figures 3 and 4). The meaning of each dimension is fairly self-evident in some cases; for example, competence could be categorized according to headings such as male or female patients (sex), age groups, place of care, or acuity of the condition. For the others, “psychomotor” refers to the skills necessary to perform technical procedures or physical examinations; “communication” refers to the skills necessary for good communication; “clinical reasoning skills” and the “patient-centred approach” are used in their usual ways.12 Three other dimension names were used as follows: “4 principles” refers to the 4 principles of family medicine of the CFPC4; “professional qualities” include the great variety of characteristics that let a physician act professionally, in both the short and long term. “Selectivity” was the term chosen by the expert groups to describe the quality of not always doing things in a routine or stereotypical fashion, but rather adapting actions to both the situation and the patient, setting priorities, and working effectively and efficiently to deal with problems. The other category includes the traditional parts of the clinical encounter (history, physical examination, investigation, diagnosis, treatment and management, follow-up, and referral). Frequencies were calculated for each, but they are reported here within 1 descriptive dimension of competence: the phase of the encounter.

Figure 3.

Determining the dimensions of competence

Figure 4.

Frequencies of the citations of the dimensions of competence in the survey: N= 2401.

As shown in Figure 4, competency was defined principally in terms of 6 dimensions: 5 concerning skills and 1 concerning the phase of the clinical encounter. Three dimensions were not used at all, and the other 3 in only 2% or 3% of the responses. Psychomotor skills appeared in this last group—the survey respondents only very rarely defined competence in terms of psychomotor skills. The phase of the encounter dimension, including all 7 phases, was frequently cited. The diagnostic parts of the encounter (history, physical examination, investigation, and diagnosis) made up 60% of the citations within this dimension; treatment and management made up 17%; follow-up and referral made up 23%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, family physicians in Canada used 99 topics, 5 skill dimensions (professional qualities, communication, selectivity, clinical reasoning, and a patient-centred approach), and the phase of the encounter to define competence. The domain of competence thus defined has clearly defined limits and is expressed in terms that are immediately familiar to all potential users. There has been no reorganization in any systematic fashion in order to try to fit the results into an established theoretical competency framework. It is our contention that this has advantages as far as accessibility is concerned, particularly for use in the clinical practice setting, which is the ideal situation for competency-based assessment.13 The terms used are familiar to clinician-teachers and learners, and can be easily used to identify and label situations deemed pertinent for evaluation.

Could or should other topics and skills have been included or added? The number of priority topics is fewer than similar lists, although we have not found any others where the limits were imposed by selecting only topics that seemed most important for demonstrating competence. The Medical Council of Canada has 220 clinical situations in its objectives for the Qualifying Examination for general licensure in Canada.14 The Royal College of General Practitioners (United Kingdom) Condensed Curriculum Guide has 32 statements leading to 1350 learning outcomes, and covers 10 domains, namely 6 core competencies, 3 application features, and psychomotor skills.15 The latter does further define competence for the many outcomes, but appears to cover the whole domain of family medicine, without selecting any elements that might be more determinant and better predictors of overall competence. Good evaluation requires a “plausible inference of overall competence from a limited number of observations.”1 If an evaluation of the present skills in the various phases of the clinical encounter over an adequate sample of these priority topics permits such an inference to be made, then the domain of competence as defined can be deemed sufficient—other topics and skills could be added, but they would not be necessary for the purposes of evaluation. It is more important to avoid including unvalidated material in an evaluation than it is to include all the possible valid material that exists. The domain as currently defined has face and content validity. Its other strength is its transparency. Even though the results reported do not include the specific interactions between the topics, skills, and phases, it is relatively easy to see what is included and what is not. There might be some nonclinical topics or tasks that could be added at a future date if appropriate consideration shows them to be useful for the determination of overall competence.

A second possible gap concerns technical or procedure skills. It is interesting, but perhaps not surprising, that the survey did not consider procedural skills as an indication of competence to start independent practice. Unless a specific practice situation requires the ability to perform certain technical procedures, then overall competence is somewhat independent of this ability. Competence is much more than a checklist of specific technical abilities,16 and assessment that does not emphasize the other dimensions of competence, particularly at the higher levels, will not be truly effective. Notwithstanding this conclusion, once the early results of the study were known, the CFPC Board of Examiners decided that the ability to perform a limited number of procedures should be required for Certification. A sixth essential skill dimension, procedure skills, was therefore added to the domain of competence, and a priority list of procedures for assessment was developed independently by a different expert group. This has been reported elsewhere.17

Since this study began, various competency frameworks have become popular for the organization of postgraduate medical education.4,6,7 For evaluation purposes, some suggest that the domain of competence should be organized according to one of these frameworks. While these frameworks do appear to be beneficial for curriculum purposes, they are confusing and can be counterproductive as far as competency-based assessment is concerned8; therefore, we have preferred to maintain the topic-skill-phase structure for what will eventually be competency-based evaluation objectives. The frameworks can usefully identify some pertinent nonclinical topics to add to the list, but these might not be necessary for plausible inferences about overall competence in family medicine. Govaerts18 strongly supports the efforts of Albanese and colleagues8 to bring some clarity to the identification and definition of competencies, but has concerns about oversimplification of the process. He states that “effective assessment programmes … will not be confined to standardized tests or checklists; workplace-based assessments involving professional judgements will have a prominent place in these assessment programmes.”18 We do not believe that describing a competency in the terms recommended by Albanese and colleagues automatically implies the genesis and mechanical use of simple checklists for assessment of the competencies so defined. Definition to this level is both helpful and necessary to guide workplace-based assessments involving professional judgment, especially those of a qualitative nature.

The essential skills are not yet either detailed enough or problem-specific enough to guide assessment except in a most general way. Further analysis is required to define these skills as well as their interactions with the priority topics in order to reach the required level of problem specificity for successful assessment.2,8 This has been done as the second part of the overall project and is reported elsewhere.19

Limitations

The absence of demographic data on the survey respondents, even though they were drawn from a group previously selected to be representative of Canadian family physicians, makes it impossible to compare them with Canadian family physicians as a whole. We cannot, therefore, infer with certainty that the survey responses reflect the views of the larger group. A validation survey has been done to verify priority topic choices by a stratified and representative sample of family physicians from across the country. The results will be reported elsewhere.

Concerns could also be raised that the results of the survey might be different if done today, rather than more than 10 years ago. This might be true if we were talking about specific treatments or investigative modalities or specific presentations, but we are not. The particular ways in which topics that present must be dealt with by a family physician do evolve, but the topics themselves change little. Similarly the exact competent use of the essential skills can change slowly, but the generic skills themselves are more enduring. Periodic review will be desirable, but these first layers of a definition of competence for the purposes of assessment are likely to remain operational for an extended period.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide guidance for planning assessment of competence for Certification to start the independent practice of family medicine. They define and limit the expectations for both candidates and teachers, and, as such, represent a first iteration of competency-based evaluation objectives in a model that seems most appropriate for assessing competence.10 They provide a next level of clarity for medical competence as defined by Epstein and Hundert,3 but further definition is required, particularly with respect to the specific interactions among the topics and the skill dimensions of competence.8 Once this has been done, it would be reasonable to state that a candidate who can demonstrate competency using the 6 essential skills, over an adequate sample of the priority topics, in the appropriate phases of the clinical encounter, does deserve Certification to start the independent practice of family medicine.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed under the auspices of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. All necessary support for this work was provided by the College.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Competency-based assessment requires a detailed and operational definition of competence to guide that assessment.

Family physicians define the domain of competence in their practices in terms of essential skills, phases of the clinical encounter, and priority topics to be dealt with.

A definition of competence that is sufficient to guide assessment will require determining the interactions among the skills, phases, and priority topics.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Toute évaluation de compétence exige une définition détaillée et opérationnelle de cette compétence qui pourra alors servir de guide à cette évaluation.

Selon les médecins de famille, le domaine de la compétence dans leur pratique correspond à certaines habiletés essentielles, aux phases de l’expérience clinique et aux sujets qui doivent être réglés en priorité.

Pour que la définition de la compétence soit suffisamment précise pour servir de guide à l’évaluation, on devra nécessairement déterminer les interactions entre ces habiletés, ces phases et ces sujets prioritaires.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors were responsible for the conceptual development of the project, the design of the study, data collection, writing the draft, and editing the final manuscript. Dr Allen had the additional responsibility of writing the final manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Kane MT. The assessment of professional competence. Eval Health Prof. 1992;15(2):163–82. doi: 10.1177/016327879201500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Vleuten CPM. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1996;1(1):41–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00596229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.College of Family Physicians of Canada . Standards for accreditation of residency training programs. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2006. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Education/Red%20Book%20Sept.%202006%20English.pdf. Accessed 2011 Jun 30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neufeld VR, Maudsley RF, Pickering RJ, Turnbull JM, Weston WW, Brown MG, et al. Educating future physicians for Ontario. Acad Med. 1998;73(11):1133–48. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Ottawa, ON: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . ACGME outcome project. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanese MA, Mejicano G, Mullan P, Kokotailo P, Gruppen L. Defining characteristics of educational competencies. Med Educ. 2008;42(3):248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McWhinney IR. A textbook of family medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klass D. A performance-based conception of competence is changing the regulation of physicians’ professional behavior. Acad Med. 2007;82(6):529–35. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805557ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine. Transforming the clinical method. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):361–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Objectives for the qualifying examination. Ottawa, ON: Medical Council of Canada; 2011. Medical Council of Canada [website] Available from: www.mcc.ca/Objectives_Online. Accessed 2011 Jun 30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley B, Haynes J, Field S. The condensed curriculum guide: for GP training and the new MRCGP. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks MA. Medical education and the tyranny of competency. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(1):90–102. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetmore SJ, Rivet C, Tepper J, Tatemichi S, Donoff M, Rainsberry P. Defining core procedure skills for Canadian family medicine training. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1364–5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/51/10/1364.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2011 Jun 30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govaerts MJ. Educational competencies or education for professional competence? Med Educ. 2008;42(3):234–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence K, Allen T, Brailovsky C, Crichton T, Bethune C, Donoff M, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine. Key-feature approach. Can Fam Physician. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]