Abstract

Objective

To determine the percentage of family medicine residency programs that have pharmacists directly involved in teaching residents, the types and extent of teaching provided by pharmacists in family medicine residency programs, and the primary source of funding for the pharmacists.

Design

Web-based survey.

Setting

One hundred fifty-eight resident training sites within the 17 family medicine residency programs in Canada.

Participants

One hundred residency program directors who were responsible for overseeing the training sites within the residency programs were contacted to determine the percentage of training sites in which pharmacists were directly involved in teaching. Pharmacists who were identified by the residency directors were invited to participate in the Web-based survey.

Main outcome measures

The percentage of training sites for family medicine residency that have pharmacists directly involved in teaching residents. The types and the extent of teaching performed by the pharmacists who teach in the residency programs. The primary source of funding that supports the pharmacists’ salaries.

Results

More than a quarter (25.3%) of family medicine residency training sites include direct involvement of pharmacist teachers. Pharmacist teachers reported that they spend a substantial amount of their time teaching residents using a range of teaching modalities and topics, but have no formal pharmacotherapy curriculums. Nearly a quarter (22.6%) of the pharmacists reported that their salaries were primarily funded by the residency programs.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have a role in training family medicine residents. This is a good opportunity for family medicine residents to learn about issues related to pharmacotherapy; however, the role of pharmacists as educators might be optimized if standardized teaching methods, curriculums, and evaluation plans were in place.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer le pourcentage des programmes de résidence en médecine familiale où des pharmaciens participent à l’enseignement aux résidents, le type et l’ampleur de l’enseignement qu’ils donnent dans ces programmes et la principale source de financement pour les pharmaciens.

Type d’étude

Enquête via le WEB.

Contexte

Cent cinquante-huit sites de formation pour résidents parmi les 17 programmes de résidence en médecine familiale du Canada.

Participants

Cent directeurs de programme de résidence responsables de la supervision des sites de formation où des pharmaciens participaient directement à l’enseignement. Les pharmaciens que les directeurs avaient identifiés ont été invités à participer à l’enquête via le WEB.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Le pourcentage des sites de formation pour la résidence en médecine familiale où des pharmaciens participent directement à l’enseignement aux résidents. Le type et l’ampleur de l’enseignement dispensé dans ces programmes par les pharmaciens. La principale source des fonds servant à payer les pharmaciens.

Résultats

Dans plus d’un quart (25,3%) des sites pour la résidence en médecine familiale, des pharmaciens participaient directement à l’enseignement aux résidents. Les professeurs pharmaciens ont déclaré qu’ils consacraient une partie importante de leur temps à l’enseignement aux résidents en utilisant diverses sujets et modalités d’enseignement, sans toutefois avoir des programmes de cours déterminés. Près d’un quart des pharmaciens (22,6%) ont déclaré que leur salaire provenait principalement des programmes de résidence.

Conclusion

Les pharmaciens ont un rôle à jouer dans la formation des résidents en médecine familiale. Pour ces résidents, c’est une excellente occasion de s’informer de questions en rapport avec la pharmacothérapie; le rôle des professeurs pharmaciens pourrait toutefois être amélioré si on utilisait des méthodes d’enseignement, des programmes de cours et des modes d’évaluation standardisés.

Pharmacists’ involvement in family medicine residency programs has been documented for more than 30 years.1–4 It has been suggested that using pharmacists to teach medical residents will not only improve the residents’ competence and confidence in managing complex medication regimens, but also teach residents how to collaborate with pharmacists after they have entered practice.5

Three surveys of family medicine residency programs published in 1981, 1990, and 2002 found that 25% to 29% of residency programs in the United States reported having the direct involvement of a pharmacist with a dual role of clinical consultant and resident educator.1–3 Although the percentage of residency programs using pharmacists was consistent across all 3 studies (25% to 29%), some aspects of their roles were not. Pharmacists working in the residency programs in 2002 were more likely to provide direct patient care services, teach residents using formal pharmacotherapy curriculums, receive salaries directly from the residency programs, and hold academic appointments in faculties of medicine than pharmacists in the earlier surveys. For example, in 2002 pharmacists spent 37% of their time providing direct patient care; 52% of pharmacists held academic appointments in faculties of medicine; and 32% of positions were fully funded by the residency programs.3

A similar Canadian survey, published in 1994, found that the direct involvement of pharmacists within family medicine residency programs in Canada was limited compared with those in the United States.4 This study found that only 13.8% of Canadian residency programs reported having pharmacist educators. In addition, none of the pharmacists in this survey reported that their salaries were primarily funded by the residency programs and none appeared to teach on the basis of a formal pharmacotherapy curriculum.4 Much has changed with the Canadian health system since this survey was published. In 2002 the Romanow Report called for more flexibility and sharing of responsibilities among health care professionals.6 Pharmacists are now moving out of the dispensary and playing a greater role in collaborative patient care environments.7,8 Recent evidence has proven the value of having pharmacists located within family physician practices9–11; consequently, many family practices (including academic residency training sites) in Canada have received funding to hire consultant pharmacist educators. Therefore, it is useful to update the Canadian survey published in 1994.4

This study aimed to determine the percentage of family medicine residency programs with the direct involvement of pharmacists who teach residents, the types and extent of teaching provided by pharmacists in family medicine residency programs, and the primary source of funding for the pharmacists.

METHODS

The websites of the 17 family medicine residency programs were accessed in July 2009 to identify the names and contact information of the residency directors. Each residency director was then contacted by e-mail in July 2009 and asked how many core training sites they had in their programs and which (if any) of the core training sites had pharmacists directly involved in teaching residents. All training sites identified by the directors were included in the study because each site represents a discrete location in which a pharmacist could be directly involved in resident teaching.

A 24-question Web-based survey was developed (using previously published surveys as guides1–4) to collect information regarding pharmacist demographics and clinic description, pharmacist roles in the clinic, types and extent of teaching provided to residents, and the primary source of funding for the pharmacists. Before use, the survey was pilot-tested on 3 pharmacists and 3 nonpharmacists. Modifications were made to the questionnaire based on the pilot-test results.

Pharmacists who were identified by the residency directors as being directly involved in teaching within the residency programs were sent e-mail invitations (in July and August 2009) to participate in the survey. This e-mail contained an explanation of the project and a link to the Web-based survey. Pharmacists provided informed consent to participate just before completing the survey. Two e-mail reminders were sent at 2-week intervals to pharmacists who did not respond to the initial invitation.

Data were collated by a Web-based program (Survey Monkey) and were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The study was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board on July 23, 2009.

RESULTS

Response rate

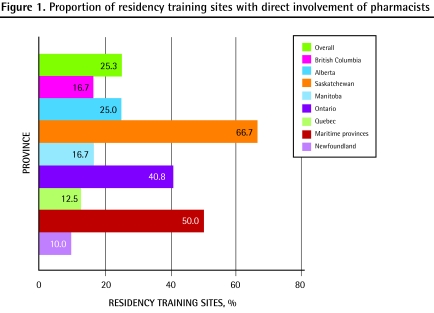

One hundred residency directors were identified as being responsible for 158 core training sites within the 17 residency programs in Canada. Most (86.0%) of the 100 residency directors responded to the initial e-mail asking which of their training sites directly involved pharmacists in resident teaching. These 86 directors reported that 25.3% (40/158) of the training sites directly involved pharmacists in resident teaching (provincial breakdown in Figure 1). All 40 pharmacists identified by the directors were invited to take part in the Web-based survey, and 80.0% (32/40) of the pharmacists responded to the survey.

Figure 1.

Proportion of residency training sites with direct involvement of pharmacists

Pharmacists’ demographics

Most pharmacist respondents were women (64.5%), were younger than 45 years of age (77.5%), lived in large urban centres (90.3%), and had postgraduate (PharmD or MSc) training (75.8%). Most of the residency training sites (87.1%) had 1 or 2 pharmacists providing service to the clinics. Approximately one-third of training sites had access to a pharmacist 1 to 2 days per week; one-third had access to a pharmacist 2.5 to 3.5 days per week; and one-third had access 4 to 5 days per week.

Overview of pharmacist roles

More than 90% of pharmacists responded that, as part of their role in a family medicine clinic, they provided direct patient care (93.5%), drug information searches for faculty and residents (93.5%), and direct teaching of family medicine residents (90.3%) regularly. In addition, 83.9% of pharmacists reported that they regularly provided patient education sessions, and 67.7% reported that they regularly were involved with research in the clinic.

Types and extent of teaching

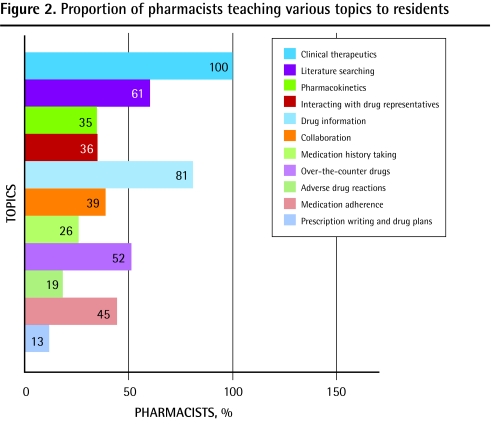

Pharmacists reported using a range of teaching modalities. The most common teaching methods used were answering drug information questions in a way that teaches residents how to find answers on their own (96.8%), informal teaching provided during patient care provision (93.5%), formal lectures (61.3%), and shadowing or mentoring (38.7%).

None of the pharmacists reported teaching according to a formal curriculum provided by the residency program. The most common topics taught by the pharmacists are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proportion of pharmacists teaching various topics to residents

When asked in more detail regarding the extent of time spent teaching family medicine residents, 41.9% of pharmacists reported that they spent 30% or more of their overall time in the clinic teaching residents (and 25.8% of pharmacists spent ≥ 50% of their time teaching).

Funding sources

Most pharmacists (61.3%) reported having their salaries primarily funded by provincial health ministries (ie, a hospital, health region, or family health team); only 22.6% were primarily funded by the residency program or the associated faculty of medicine. Interestingly, 6.5% were funded by a faculty of pharmacy.

DISCUSSION

More than a quarter of the 158 residency training sites (25.3%) had pharmacists directly involved in teaching residents in 2009 compared with the lower percentage (13.8%) in the 1994 survey.4 The current rate of pharmacist involvement is strikingly similar to that reported in 3 American surveys published in 1981, 1990, and 2002 (25% to 29%).1–3

In 2002 Dickerson et al3 reported that 38.5% of pharmacists responding from family medicine residency programs in the United States had formal pharmacotherapy curriculums and that these curriculums were coordinated by pharmacists 82.4% of the time. Although the topics and teaching modalities used by the pharmacists in our survey appear to be useful and relevant, none of the respondent pharmacists reported teaching according to a formal pharmacotherapy curriculum. This likely explains the finding that the pharmacists who responded to our survey were clearly not using a common set of teaching methods or topics in their residency programs. This suggests that either the programs did not have formal pharmacotherapy curriculums or the pharmacists were unaware of them. In either case, this result suggests that Canadian family medicine residency programs might consider following their American colleagues by developing formal pharmacotherapy curriculums for the programs and the pharmacist teachers.

This survey also found that only 22.6% of pharmacists working in family medicine residency programs were primarily funded by the residency program. Consequently, it appears that most pharmacists who teach in family medicine residency programs in Canada are not paid by the residency program. However, this rate is actually much higher than the 1994 survey, in which none of the responding pharmacists were funded by the residency programs.4 Although it is impressive that so many residency programs in Canada have gained access to pharmacist teachers without having to contribute a large amount of funding, the current arrangement might not be sustainable if the health ministries that primarily fund these positions instruct the pharmacists to spend less of their time supporting resident teaching.

Despite the fact that most pharmacists who responded to this survey (61.3%) reported that their salaries were primarily funded by provincial health ministries (presumably to provide patient care services), the pharmacists in this survey were spending a substantial amount of their time in the clinic teaching residents (41.9% of pharmacists reported that they spent ≥ 30% of their time teaching residents). These results suggest that residency programs have identified the value of the teaching role of pharmacists and have successfully incorporated a large number of pharmacists into their programs to teach at a modest financial cost to the residency programs.

Limitations

Although the response rate was good (86.0% of residency directors responded to the invitation and 80.0% of pharmacists responded to the survey), the survey relied on pharmacists’ ability to recall what they teach, how they teach, and how often they teach. Pharmacists were not asked to record their daily workload. In addition, the survey did not address the attitudes or satisfaction of the residents and faculties regarding the role of pharmacists, and it did not address the educational effect of pharmacists’ teaching on the quality of resident training. Future research could focus on measuring these attitudinal, satisfaction, and resident learner outcomes.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have an important role in the training of family medicine residents based on the finding that more than 25% of residency training sites have direct access to pharmacists who spend a substantial amount of time teaching residents. These pharmacists use a variety of methods to teach a range of topics with no clear pharmacotherapy curriculum in place, and most of the pharmacist teachers (77.4%) are not funded by the residency programs. Having pharmacists teach residents is a good opportunity for family medicine residents to learn about issues related to pharmacotherapy; however, the role of pharmacists as educators might be optimized if standardized teaching methods, curriculums, and evaluation plans were in place.

Acknowledgments

Financial support in the form of an unrestricted research grant was received from the College of Pharmacy and Nutrition at the University of Saskatchewan.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

It has been suggested that using pharmacists to teach medical residents will not only improve residents’ competence and confidence in managing complex medication regimens, but also teach residents how to collaborate with pharmacists after they have entered practice.

The goal of this study was to determine the percentage of family medicine residency programs that directly involved pharmacists who teach residents, the types and extent of teaching provided by pharmacists in family medicine residency programs, and the primary source of funding for the pharmacists.

A substantial proportion of the 158 residency training sites (25.3%) had pharmacists directly involved in teaching residents compared with the lower percentage (13.8%) in a 1994 Canadian survey.

More than 90% of pharmacists responded that, as part of their role in the family medicine clinic, they provided direct patient care (93.5%), drug information searches for faculty and residents (93.5%), and direct teaching of family medicine residents (90.3%) on a regular basis. In addition, 83.9% of pharmacists reported that they regularly provided patient education sessions, and 67.7% reported that they regularly were involved with clinic research.

More than three-quarters (77.4%) of pharmacist teachers reported that they were not funded primarily by the residency programs.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

On a suggéré que l’emploi de pharmaciens pour enseigner aux résidents en médecine non seulement améliore la compétence et la confiance des étudiants dans la gestion de médications complexes, mais les incite aussi à collaborer avec les pharmaciens quand ils sont en pratique.

Le but de cette étude était de déterminer le pourcentage des programmes de résidence en médecine familiale où des pharmaciens enseignent directement aux résidents, le type et l’ampleur de l’enseignement qu’ils donnent dans ces programmes et la principale source de rétribution pour les pharmaciens.

Dans une proportion importante des 158 sites de formation pour la résidence (25,3%), des pharmaciens enseignaient directement aux résidents, comparativement à un pourcentage plus faible (13,8%) observé dans l’enquête canadienne de 1994.

Plus de 90% des pharmaciens ont déclaré qu’en tant que participants aux cliniques de médecine familiale, ils prodiguaient des soins directs aux patients (93,5%), effectuaient des recherches sur les médicaments pour les professeurs et les résidents (93,5%) et enseignaient directement et sur une base régulière aux résidents en médecine familiale (90,3%). De plus, 83,9% des pharmaciens ont déclaré qu’ils donnaient régulièrement des séances de formation aux patients et 67,7% qu’ils participaient régulièrement à la recherche clinique.

Plus des trois quarts (77,4%) des pharmaciens enseignants ont déclaré qu’ils n’étaient pas rétribués principalement par les programmes de résidence.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Dr Jorgenson took the lead in developing the research methodology and in running the research project. Dr Jorgenson assisted in the interpretation of the data and was the main author of the manuscript. Dr Muller assisted in the development of the research methodology and assisted in running the research project. Dr Muller assisted in the interpretation of the data and reviewed the manuscript. Dr Whelan assisted in the development of the research methodology; assisted in the interpretation of the data and in reviewing the manuscript. Ms Buxton assisted in the development of the research methodology; assisted in the interpretation of the data; and assisted in reviewing the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Johnston TS, Heffron WA. Clinical pharmacy in family practice residency programs. J Fam Pract. 1981;13(1):91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaughnessy AF, Hume AL. Clinical pharmacists in family practice residency programs. J Fam Pract. 1990;31(3):305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickerson LM, Denham AM, Lynch T. The state of clinical pharmacy practice in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 2002;34(9):653–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan AM, Burge F, Munroe K. Pharmacy services in family medicine residencies. Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:468–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson EA. The role of pharmacists in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 2002;34(9):692–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Available from: http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf. Accessed 2011 May 11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Task Force on a Blueprint for Pharmacy . Blueprint for pharmacy: the vision for pharmacy. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Management Committee . Moving forward: pharmacy human resources for the future. Final report. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pottie K, Farrell B, Haydt S, Dolovich L, Sellors C, Kennie N, et al. Integrating pharmacists into family practice teams. Physicians’ perspectives on collaborative care. Can Fam Physician. 2008. pp. 174–5.e1–5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/54/12/1714.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2011 May 11. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, Farrell B, Austin Z, Rodriguez C, et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(6):913–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.29. Epub 2008 Mar 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, Lenarz LA, Heaton AH, Wadd WB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2008;48(2):203–11. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]