Abstract

This paper presents a new signal transduction method, called Label-Acquired Magnetorotation (LAM), for the measurement of proteins in solution. We demonstrate the use of LAM to detect the protein thrombin using aptamers, with an LOD (limit of detection) of 300 pM. LAM is modeled after a sandwich assay, with a 10 µm nonmagnetic “mother” sphere as the capture component, and with 1 µm magnetic “daughter” beads as the labels. The protein-mediated attachment of daughter beads to the mother sphere forms a rotating sandwich complex. In a rotating magnetic field, the rotational frequency of a sandwich complex scales with the number of attached magnetic beads, which scales with the concentration of the protein present in solution. This paper represents the first instance of the detection of a protein using LAM.

Introduction

One of the primary goals in a point-of-care diagnostic system is measuring the concentration of a protein in order to assess the overall health of a patient. Effective screening methods have been shown to improve patient health, such as a recent large study, on a population at high risk for lung cancer, that found a 20% decrease in mortality due to better early screening 1–2. There are three primary components in a protein measurement system: the target biomarker to be measured, the affinity molecules used to capture the target, and the method of transducing a successful binding event into a quantifiable signal. There are several popular signal transduction methods, including optical, electrochemical and magnetic schemes. This paper presents the development of a new, optomagnetic signal transduction method, called label-acquired magnetorotation (LAM), which has the potential for eventual incorporation into a point-of-care diagnostic system. Previously, we published proof-of-principle work demonstrating the concept of LAM using a biotin and streptavidin system as protein and aptamer mimics.3 Here, we demonstrate the next step by showing LAM used to detect proteins in solution using aptamers.

The most common set-up for measuring the concentration of a protein in solution is the sandwich assay, where the target is first captured by an affinity molecule bound to a surface, and is then sandwiched by a signal transducer attached to another affinity molecule.4 Optical methods include sandwich-based ELISA,5–7 fluorescence signaling8–10 or quantum dots,11–12 and the non-sandwich based surface plasmon resonance methods.13–15 The electrochemical methods include sandwich-based amperometric enzymatic methods16–17 and non-sandwich-based impedimetric sensing.18–19

Magnetic beads are advantageous for use as signal transducers because they are biologically inert, are physically stable under most biological environments, and biological materials have no native magnetism that could interfere with a signal from the beads.20–21 Due to these advantages, magnetic beads have been used as signal transducers in a variety of applications, including giant magnetoresistance (GMR),22–24 Hall probes,25–26 and magnetic relaxation.27–28 Additionally, magnetic beads have been used as carriers for magnetophoresis and to facilitate detection by other signal transduction methods.29–31 In contrast, the method described here uses optical detection of the magnetic behavior.

The beads used in this study are 1 µm commercial beads that exhibit superparamagnetic behavior (DynaBeads®). These beads are composed of maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles, with a mean diameter of 8 nm dispersed within a polymer bead. The beads are 25.5% Fe by mass.32 In the absence of a magnetic field, these beads have no net magnetization, but within a magnetic field, the magnetic moments of the beads align with the field and they become strongly magnetic.32

The work presented here uses these beads in a rotating magnetic field. Previous studies have examined and characterized the behavior of these beads in alternating magnetic fields. It was first shown that in a one-dimensional alternating magnetic field, the dominant relaxation mechanism of such superparamagnetic beads is the Neel relaxation of the nanoparticles embedded within the bead.33 It was later shown that in a two-dimensional rotating magnetic field, at high driving frequencies, the dominant mechanism driving the rotation of these same beads is also related to Neel relaxation.34 Brownian rotational effects are not significant for these beads because the time constant for the Brownian relaxation of a sphere with diameter on the order of a micron is on the order of seconds, while the time constant for the Neel relaxation of the inner magnetic nanoparticles is on the order of nanoseconds.

In a two-dimensional rotating magnetic field, at low driving frequencies, magnetic beads are able to rotate synchronously with the field. At higher driving frequencies (above the critical frequency35) these beads are not able to stay in phase with the field, and rotate asynchronously. In the asynchronous regime, the rotational frequency of the bead depends on a number of factors, including the magnetic moment of the bead, the amplitude and frequency of the driving field, the hydrodynamic volume of the bead, and the viscosity of the solution. This asynchronous rotation has already been demonstrated to be a useful tool for making biological measurements, specifically for monitoring the growth and antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria.36–39

Thrombin is a coagulation factor that is the first step in the coagulation cascade that leads to the formation of a blood clot, so as to stem blood loss. Aptamers are single- or double-stranded nucleic acid sequences that bind to proteins through favorable electrostatic interactions, with an affinity similar to that of an antibody.40–41 One of the earliest aptamers to be identified binds to the fibrin exosite on thrombin, and has the following 15-base pair sequence: 5’-GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG-3’.42 Later, a second, 29-base pair sequence against thrombin was identified, which binds to the heparin exosite: 5’-GTCCGTGGTAGGGCAGGTTGGGGTGAC-3’.43 Since these aptamers bind to opposite sides of the thrombin molecule, they represent an ideal system for the development of an aptamer-based sandwich assay, and have been used in the development of many such assays.44–46

Experimental

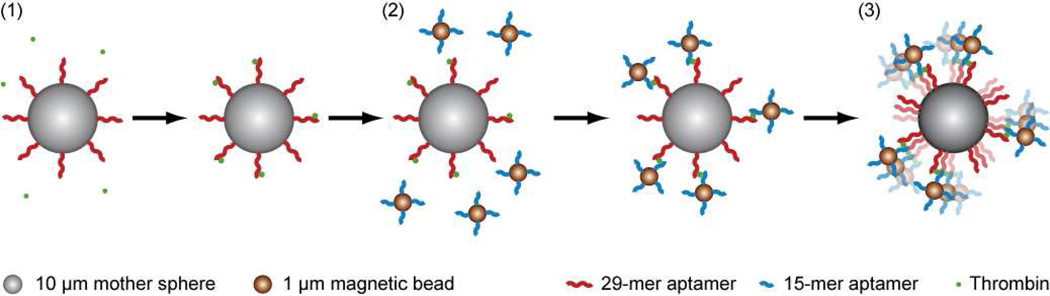

A schematic of LAM is shown in Figure 1. The mother spheres used were 10 µm nonmagnetic streptavidin-coated ProActive microspheres (Bangs Labs, Fishers, IN). The daughter beads used were Dynal MyOne 1 µm streptavidin-coated DynaBeads that exhibit superparamagnetic behavior (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Human α-thrombin was purchased from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Biotinylated aptamers (with a 5’ polyT20 tail for improved binding)47 were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Salts (NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, EDTA and Tris-HCl) and Tween-20 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) Blocker solution was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Zero-thickness glass coverslips were obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA). OPI Top Coat clear nail protector was purchased from OPI Products Inc. (North Hollywood, CA). Formulations for wash buffer, aptamer binding buffer, and thrombin binding buffer (containing 0.1% BSA, and with the addition of 10 mM KCl48) were based on previously published work.47

Figure 1.

Schematic of LAM with thrombin as the analyte. (1) 10 µm nonmagnetic mother spheres coated with the 29-mer anti-thrombin aptamer are mixed with thrombin, which binds to the mother spheres. (2) 1 µm magnetic beads coated with the 15-mer anti-thrombin aptamer are mixed with the thrombin-coated mother spheres. The magnetic beads bind to the thrombin attached to the mother sphere, forming a sandwich complex. (3) The sandwich complex is transferred to a rotating magnetic field, where the rotational frequency of the sandwich complex depends on the number of attached magnetic beads.

An aliquot of 50 µL of the magnetic beads was washed three times by magnetic separation in 200 µL of wash buffer, then resuspended in 500 µL of aptamer binding buffer, at a concentration of 1 mg/mL beads in a microcentrifuge tube. An aliquot of 50 µL of the mother spheres was washed three times by centrifugation in 200 µL of wash buffer, then resuspended in 1 mL of aptamer binding buffer, at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL spheres. A 10 µL aliquot of biotinylated-15-mer thrombin binding aptamer was added to the superparamagnetic beads, and a 10 µL aliquot of biotinylated-29-mer thrombin binding aptamer was added to the mother spheres. The two solutions were briefly vortexed then incubated on an end-over-end rotator for 1 hour. They were then washed (by magnetic separation and centrifugation, respectively) three times and resuspended in thrombin binding buffer. An aliquot of human α-thrombin was serially diluted over a concentration range of 50 nM to 100 pM in thrombin binding buffer. In a separate tube, 100 µL of thrombin solution were mixed with 40 µL of mother sphere solution, and then incubated on an end-over-end rotator for 90 minutes. Finally, 10 µL of magnetic bead solution were added to the mother spheres and thrombin and incubated on an end-over-end rotator for 90 minutes.

Microfluidic flow cells were prepared from two zero-thickness glass coverslips (the bottom coverslip was coated with a thin layer of clear nail protector, to reduce particle sticking) separated by a single piece of double-sided Scotch tape (3M, St. Paul, MN). The solution containing the mother spheres and the magnetic beads was diluted with 140 µL of 0.2% Tween-20, and 20 µL of this solution were pipetted into the coverslip flow cell. The coverslip flow cell was then placed in a rotating magnetic field (amplitude 1.25 mT, frequency 200 Hz) built from two pairs of orthogonally-oriented Helmholtz coils driven by a pair of sinusoidal waves 90 degrees out of phase with each other. The magnetic field was located on top of an IX71 inverted microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY). The rotation of the sandwich complexes was observed through a 100× oil-immersion objective, imaged through a Basler piA640-210gm camera (Basler, Highland, IL) and recorded by an in-house program written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Videos were analyzed using the St. Andrews particle tracker49 and an in-house program written in MATLAB.

Theory

The theory governing the behavior of superparamagnetic particles and beads in rotating magnetic fields has been discussed in detail elsewhere.3, 33–34, 50 Briefly, starting from the equation for the magnetic torque, τ = m × B, where m is the magnetic moment of the bead and B is the external magnetic field, assuming steady-state rotation (allowing for the equating of rotational driving forces with drag forces, , where κ is the shape factor (equal to 6 for a sphere), η is the viscosity of the surrounding fluid, and VH is the hydrodynamic volume), and making some simple substitutions, B = μ0H, m = MVm, M=χH and χ = χ'−iχ" (where H is the magnetizing field, μ0 is the permeability of free space, M is the volume magnetization, Vm is the volume of the bead’s magnetic material, χ is the bead susceptibility, χ’ is the real component of the bead susceptibility and χ” is the imaginary component of the bead susceptibility) we can get an expression for the rotational frequency dθ/dt:

| (1) |

The definition of imaginary susceptibility, χ”, is , where χ0 is the DC susceptibility, Ω is the frequency of the driving field. The definition of Neel relaxation time, τN,is , where τ0 is the attempt frequency, K is the anisotropy constant (equal to 5 × 104 J/m3 for maghemite nanoparticles51), Vp is the volume of the maghemite nanoparticles, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the ambient temperature. The magnetic nanoparticles are not perfectly uniform; for a size distribution with n intervals, with average nanoparticle volume Vp, the total volume of nanoparticles in the distribution is Vn. The expression for Neel relaxation time, τN, can be substituted into the expression for imaginary susceptibility, χ”, which, along with considering the effects of the nanoparticle size distribution, can then be substituted into equation (1) to create a single expression describing the rotation of a superparamagnetic object in a magnetic field:34

| (2) |

In the low driving frequency (Ω ≪ 1 kHz) regime used in this paper, , so equation (2) can be simplified:

| (3) |

Results and Discussion

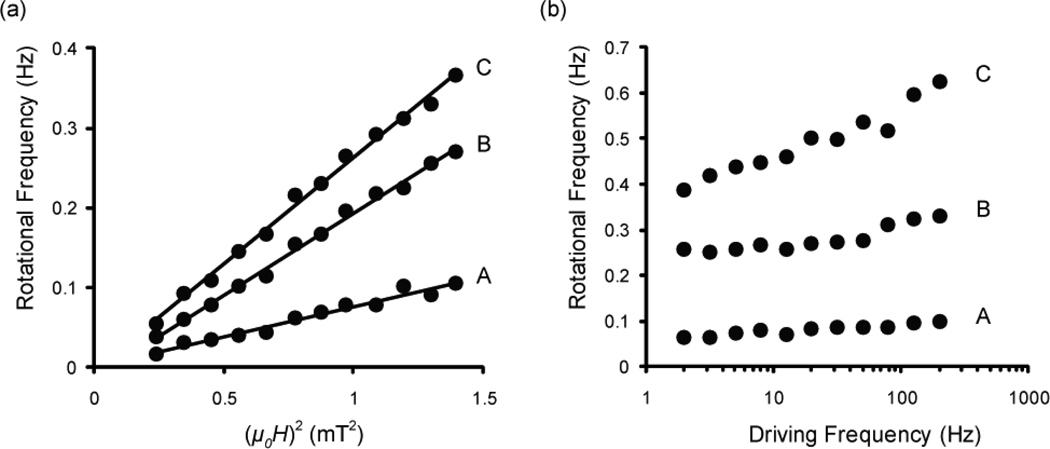

To test whether the sandwich complexes follow the model of equation (3), we observed the response of the sandwich complexes to changes in amplitude and frequency. Holding all variables except for field amplitude constant, equation (3) reduces to . Figure 2a shows indeed that the rotational frequency of a sandwich complex is directly proportional to the square of the amplitude of the driving field. Holding all variables constant except for field driving frequency, equation (3) reduces to Figure 2b shows that the rotational frequency of a sandwich complex does increase with the frequency of the driving field, but it does not exactly demonstrate the linear relationship that equation (3) suggests.

Figure 2.

(a) Amplitude response curves showing that the rotational frequency of a sandwich complex is proportional to the square of the amplitude of the driving field (with B=μ0H). The data are fit with a linear trendline with r2 values of (A) 0.968, (B) 0.995, and (C) 0.994. (b) Frequency response curves showing that the rotational frequency of a sandwich complex increases with an increase in the frequency of the driving field.

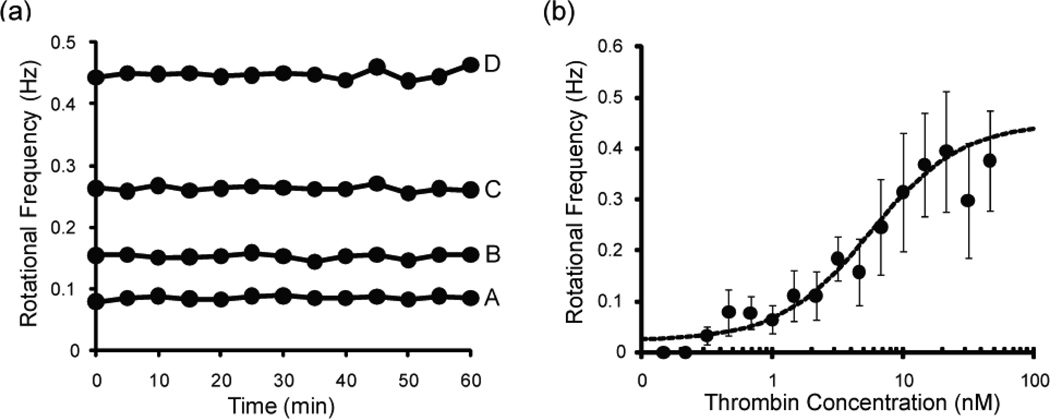

We examined the stability of the rotation of sandwich complexes over 60 minutes of observation. The rotational frequency of four sandwich complexes was measured every 5 minutes for 60 minutes, as shown in Figure 3a. The coefficient of variation (standard deviation divided by the mean, times 100%) of the complexes (A–D) was 3.3%, 2.5%, 1.5% and 1.6%, respectively, demonstrating that the rotation of a sandwich complex is fairly stable over a 60 minute observation period. All other measurements reported here were made within an hour of the sandwich complexes being injected into the coverslip fluidic cell.

Figure 3.

(a) The rotational frequency of four sandwich complexes measured every five minutes over the course of an hour. The rotational frequency means, ± SD (CV%) of the four sandwich complexes (A–D) are 0.0856 ± 0.0028 Hz (3.3%), 0.1523 ± 0.0038 Hz (2.5%), 0.263 ± 0.0040 Hz (1.5%) and 0.448 ± 0.0073 Hz (1.6%), respectively. This demonstrates that the rotation of the sandwich complexes is stable over time. (b) Dose-response curve for the detection of thrombin by LAM. The data are fit by a four-parameter logistic equation (r2 = 0.971). Each data point represents the average ± SD of 15 sandwich complexes.

A dose-response curve of LAM used for measuring the concentration of thrombin in solution is shown in Figure 3b. At each thrombin concentration, the rotation of 15 sandwich complexes was measured, and each point in the figure represents the average of those 15 measurements (± standard deviation). The data was fit using the four-parameter logistic Hill equation.52–53 The dynamic range of the curve extends from about 1 nM to about 20 nM. Above 20 nM, the curve plateaus. Below 1 nM, there is still a detectable signal down to 300 pM. In the 300 pM to 1 nM range, there was still binding of beads to the mother sphere, but there was no significant difference between the different concentrations. Below 300 pM, no binding of beads to the mother sphere was observed. Similarly, in a control sample (no thrombin), there was also no binding detected. In the absence of the aptamers thrombin does not bind to the spheres and beads. Figure 3b demonstrates the viability of LAM as a tool for measuring the concentration of a protein in solution, with an LOD (limit of detection) of 300 pM.

Screenshots of the rotation of five of the sandwich complexes from Figure 3b are shown in Figure 4. These images show that the number of beads attached to each complex increases with the concentration of thrombin, and that the rotational frequency of the complexes increases with the number of attached beads. These images also show that a qualitative estimate of the protein concentration can be made merely by looking at the complexes under a microscope, without using rotation.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of five sandwich complexes taken through a 100× oil-immersion objective. The thrombin concentration and the rotational frequency of each complex is shown below the picture. The number of magnetic beads on and the rotational frequency of each sandwich complex appears to increase with concentration of thrombin.

One of the advantages of using the thrombin aptamers are their popularity; many groups have used these aptamers for demonstration of signal transduction techniques. When examining other methods that are sandwich-based and use single-step (non-amplified) methods, reported LODs typically are in the 0.1–1 nM range, including electrochemical detection,18, 47 quantum dots,11 Si-nanowire FETs,19 and fluorescent molecular beacons.54 There are many clinically relevant biomarkers found in plasma at concentrations around 1 nM.55–56 Within this context, we believe that LAM is certainly competitive with other detection technologies. Moreover, LAM has the advantage of simplicity, robustness and low cost, without requiring sensitive optical readers or other expensive and stationary sensing equipment.

We generated a model in MATLAB to simulate the optimal performance of LAM, assuming perfect mixing and no nonspecific interactions, based on a previously reported two-site immunoassay model.57 Considering only specific interactions, there are two primary reactions that take place in our system:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Where P is the protein of interest, Q1 is the capture aptamer, and Q2 is the detection aptamer. Also, there are two possible side reactions:

| (6) |

| (7) |

The model is carried out in two parts, capture and detection. In the capture phase, only equation (5) is considered. After the capture reaction has reached equilibrium, the detection phase commences, in which equations (5)–(8) are all considered. The rate constants for the thrombin aptamers were obtained from previously published work.58 The model is generated by simultaneously solving the six differential equations below:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

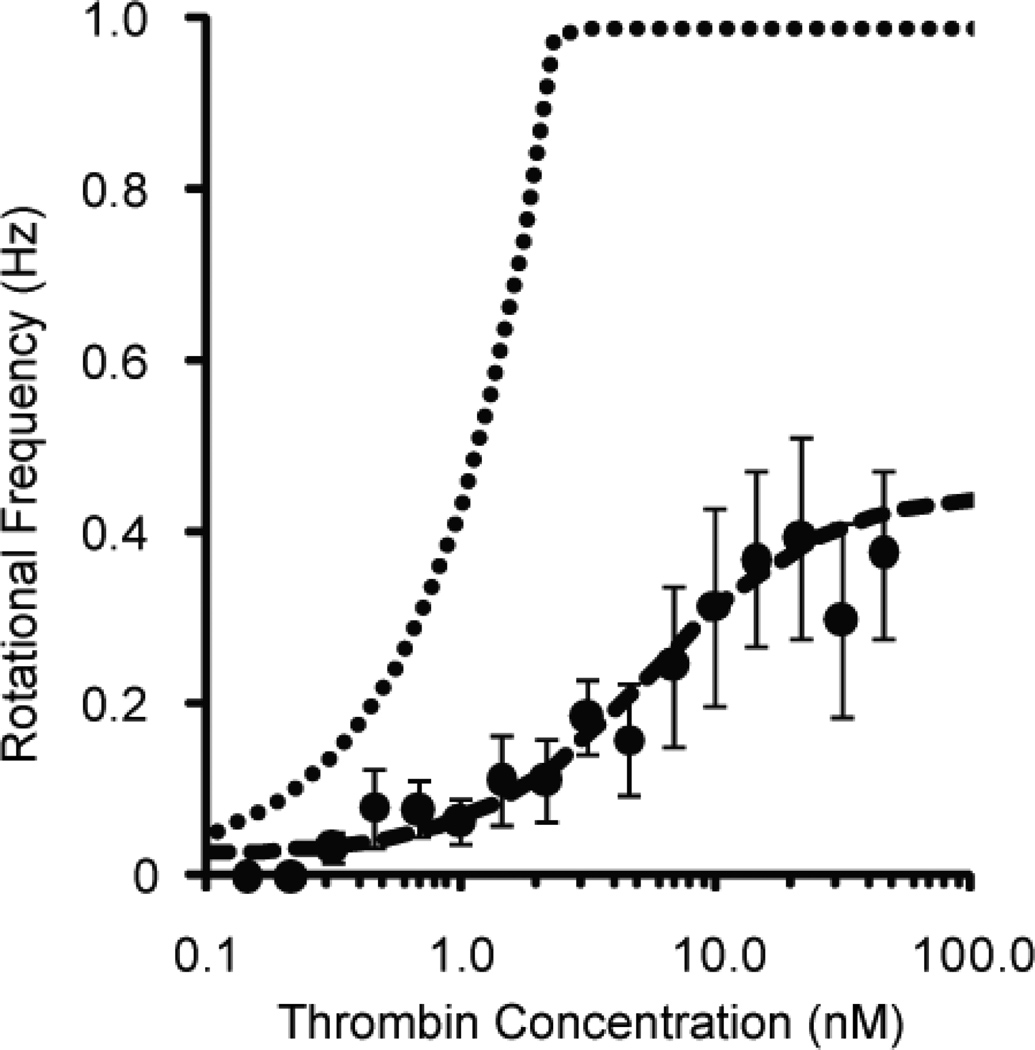

The simulated dose-response curve based on this model is shown in Figure 5. Deviations of the experimental data from this simulated dose-response curve could be due to nonspecific interactions between the aptamers and other proteins in solution, imperfect mixing, suboptimal aptamer-bead attachment, or experimental error. The rather abrupt plateau at the top of the dose-response curve is due to the saturation of the mother spheres with magnetic beads before saturation with thrombin; only a few hundred beads can bind to the mother sphere, but over a million thrombin molecules could bind to the mother sphere.

Figure 5.

Simulated dose-response curve (dotted line) for LAM from a model based on the binding kinetics of the aptamers with thrombin. Also included in the plot are experimental data (dots), from Figure 3b, and a logistic curve fit (dashed line). The abrupt plateau at the top of the predicted dose-response curve represents the saturation of the sensor.

It is our long term goal to develop LAM into a signal transduction method that is suitable for use in a point-of-care clinical setting. In order to achieve this goal, several additional steps must be taken. We plan to translate LAM off the microscope and measure the rotation of the sandwich complex using a simple, compact-disc-like, laser-and-photodiode setup59, together with automated and self-contained mixing, in a microfluidic chip. We also plan to reproduce these results in a biological fluid medium, such as serum. We believe that, after additional development, LAM will be an attractive tool for use, because it will not require fluorescence readers or a microscope, and the actual detector (the laser and photodiode) would be low-cost. We recognize that these goals will require additional work. The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the feasibility of LAM as a signal transduction method for measuring the concentration of a protein in solution, for possible future applications as a point-of-care signal transduction method.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that label-acquired magnetorotation is a viable signal transduction method for measuring the concentration of a protein in solution, with a limit of detection of 300 pM of thrombin when using the classic thrombin aptamers. We have shown that the amplitude and frequency response of a sandwich complex generally follow the behavior predicted by the equations that describe superparamagnetic bead behavior. It is our hope for the future that, with further work, LAM will be developed into a viable signal transduction method for point-of-care testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alex Hrin for creating the video capture LabVIEW program, Ron Smith for assistance with microscopy and magnetic field setup. This research was partially supported by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Scholarship and Fellowship Program, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and DHS. ORISE is managed by Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) under DOE contract number DEAC05-06OR23100. All opinions expressed in this paper are the author's and do not necessarily reflect the policies and views of DHS, DOE, or ORAU/ORISE. Additional support came from NSF/DMR grant 0455330 (RK) and NIH R21 EB009550 (RK).

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. [Date Accessed: 5/31/2011]; http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/2011/NLSTFastFacts.

- 2.NLSTRT. Radiology. 2011;258:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hecht A, Kinnunen P, McNaughton B, Kopelman R. J Magn Magn Mater. 2011;323:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekins RP. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 1989;7:155–168. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(89)80079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engvall E, Perlmann P. The Journal of Immunology. 1972;109:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho I-H, Paek E-H, Kim Y-K, Kim J-H, Paek S-H. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;632:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillet C, Fourcin M, Chevalier S, Pouplard A, Gascan H. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1995;762:407–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes MA, Petkus MM, Garcia AA, Taylor T, Mahanti P. Analyst. 2009;134:533–541. doi: 10.1039/b809665a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Li X, Prow TW, Reece LM, Bassett SE, Luxon BA, Herzog NK, Aronson J, Shope RE, Leary JF, Gorenstein DG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urdea MS, Warner BD, Running JA, Stempien M, Clyne J, Horn T. Nucleic Acids Research. 1988;16:4937–4956. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.11.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tennico YH, Hutanu D, Koesdjojo MT, Bartel CM, Remcho VT. Anal Chem. 2010;82:5591–5597. doi: 10.1021/ac101269u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su X-L, Li Y. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4806–4810. doi: 10.1021/ac049442+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soelberg SD, Stevens RC, Limaye AP, Furlong CE. Anal Chem. 2009;81:2357–2363. doi: 10.1021/ac900007c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J-G, Lee C-L, Lin H-M, Chuang T-L, Wang W-S, Juang R-H, Wang C-H, Lee CK, Lin S-M, Lin C-W. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2006;22:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinowsky TM, Quinn JG, Bartholomew DU, Kaiser R, Elkind JL. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2003;91:266–274. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyerhoff M, Duan C, Meusel M. Clin Chem. 1995;41:1378–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Z, Yan F, Chen J, Ju H. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5429–5434. doi: 10.1021/ac034213t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai H, Lee TM-H, Hsing IM. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2006;114:433–437. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KS, Lee H-S, Yang J-A, Jo M-H, Hahn SK. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:235501. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/23/235501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pamme N. Lab Chip. 2006;6:24–38. doi: 10.1039/b513005k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gijs MAM, Lacharme F, Lehmann U. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1518–1563. doi: 10.1021/cr9001929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osterfeld SJ, Yu H, Gaster RS, Caramuta S, Xu L, Han SJ, Hall DA, Wilson RJ, Sun SH, White RL, Davis RW, Pourmand N, Wang SX. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20637–20640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810822105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edelstein RL, Tamanaha CR, Sheehan PE, Miller MM, Baselt DR, Whitman LJ, Colton RJ. Biosens Bioelectron. 2000;14:805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(99)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schotter J, Kamp PB, Becker A, Pühler A, Reiss G, Brückl H. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2004;19:1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besse P-A, Boero G, Demierre M, Pott V, Popovic R. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;80:4199–4201. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandhu A, Handa H, Abe M. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:442001. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/44/442001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Sun E, Ham D, Weissleder R. Nat Med. 2008;14:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nm.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung SH, Hoffmann A, Bader SD, Liu C, Kay B, Makowski L, Chen L. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;85:2971–2973. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi J-W, Liakopoulos TM, Ahn CH. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2001;16:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(01)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes MA, Polson NA, Phayre AN, Garcia AA. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:5896–5902. doi: 10.1021/ac0104680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pamme N, Manz A. Anal Chem. 2004;76:7250–7256. doi: 10.1021/ac049183o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonnum G, Johansson C, Molteberg A, Morup S, Aksnes E. J Magn Magn Mater. 2005;293:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fannin PC, Cohen-Tannoudji L, Bertrand E, Giannitsis AT, Mac Oireachtaigh C, Bibette J. J Magn Magn Mater. 2006;303:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen XJA, Schellekens AJ, van Ommering K, van Ijzendoorn LJ, Prins MWJ. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:1937–1941. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNaughton BH, Kehbein KA, Anker JN, Kopelman R. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:18958–18964. doi: 10.1021/jp060139h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinnunen P, Sinn I, McNaughton BH, Newton DW, Burns MA, Kopelman R. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2011;26:2751–2755. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinnunen P, Sinn I, McNaughton BH, Kopelman R. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97:223701–223701-3. doi: 10.1063/1.3505492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNaughton BH, Agayan RR, Clarke R, Smith RG, Kopelman R. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91 - [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNaughton BH, Agayan RR, Wang JX, Kopelman R. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2007;121:330–340. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turek C, Gold L. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bock LC, Griffin LC, Latham JA, Vermaas EH, Toole JJ. Nature. 1992;355:564–566. doi: 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tasset DM, Kubik MF, Steiner W. J Mol Biol. 1997;272:688–698. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho H, Baker BR, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Pagba CV, Laurence TA, Lane SM, Lee LP, Tok JBH. Nano Letters. 2008;8:4386–4390. doi: 10.1021/nl802245w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao Y, Lubin AA, Heeger AJ, Plaxco KW. Angewandte Chemie. 2005;117:5592–5595. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strehlitz B, Nikolaus N, Stoltenburg R. Sensors. 2008;8:4296–4307. doi: 10.3390/s8074296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centi S, Tombelli S, Minunni M, Mascini M. Anal Chem. 2007;79:1466–1473. doi: 10.1021/ac061879p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang C-C, Cao Z, Chang H-T, Tan W. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6973–6981. doi: 10.1021/ac049158i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milne G. Optical Sorting and Manipulation of Microscopic Particles. University of St. Andrews; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Connolly J, St Pierre TG. J Magn Magn Mater. 2001;225:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodker F, Morup S, Linderoth S. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:282. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baud M. In: Methods of Immunological Analysis. Masseyeff R, editor. vol. 1. New York, NY: VCH Publishers, Inc.; 1993. pp. 656–671. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hecht AH, Sommer GJ, Durland RH, Yang X, Singh AK, Hatch AV. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82:8813–8820. doi: 10.1021/ac101106m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radi A-E, Acero Sánchez JL, Baldrich E, O'Sullivan CK. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;128:117–124. doi: 10.1021/ja053121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polanski M, Anderson NL. Biomarker Insights. 2006;2:1–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs JM, Adkins JN, Qian W-J, Liu T, Shen Y, Camp DG, Smith RD. Journal of Proteome Research. 2005;4:1073–1085. doi: 10.1021/pr0500657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodbard D, Feldman Y. Immunochemistry. 1978;15:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(78)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller J, Freitag D, Mayer G, Potzsch B. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2008;6:2105–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McNaughton BH, Kinnunen P, Smith RG, Pei SN, Torres-Isea R, Kopelman R, Clarke R. J Magn Magn Mater. 2009;321:1648–1652. [Google Scholar]