Abstract

Since the first description of an entirely intraductal epithelial proliferation of salivary gland by Chen in 1983 as an “intraductal carcinoma”, there have been several dozen reported cases with the same and various additional names including “low-grade salivary duct carcinoma”, “low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma” and “carcinoma in situ” of salivary gland. These refer to a combination of nests and cysts of varying size formed by a cellular proliferation resembling atypical ductal hyperplasia or ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. The lesions are generally entirely intraductal with low, intermediate or high-grade dysplasia. Occasional benign tumors of salivary gland, particularly Warthin tumor and rare salivary carcinomas may arise within an intraparotid lymph node. In addition, intraparotid lymph nodes are a routine location for metastatic disease. A case of a 59-year-old female with a parotid mass is described, which grossly had the appearance of a Warthin tumor. Microscopically, it was an entirely intranodal proliferation of cells with diffuse AE1/AE3 and S100 positivity. The nests and cysts were completely surrounded by a rim of non-neoplastic myoepithelial cells, which were positive for CK14, p63, SMA, MSA and calponin. The tumor cells were negative for these markers. The cells were only focally positive for AR and BRST-2. They showed negligible MIB-1 staining. This report describes, for the first time, an entirely intranodal location for a low-grade intraductal carcinoma (so-called low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma).

Keywords: Intraductal carcinoma, Low-grade salivary duct carcinoma, Low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma, Intranodal, Salivary gland tumors, Warthin tumor

Introduction

Since the first description of an entirely intraductal epithelial proliferation of salivary gland by Chen in 1983 as an “intraductal carcinoma” [1], there have been several dozen reported cases with the same and various additional names including “low-grade salivary duct carcinoma”, “low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma” and “carcinoma in situ” of salivary gland [2–7]. These all refer to a combination of nests and cysts of varying size formed by a cellular proliferation resembling atypical ductal hyperplasia or ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. The lesions are generally entirely intraductal with low, intermediate or high-grade dysplasia and they may show microinvasion [2, 3] or rarely can have a widespread invasive component [8]. Their relationship to cystadenocarcinomas and conventional salivary duct carcinomas is a matter of controversy, and whether they are even related to one another has not been extensively studied.

Warthin tumors of salivary gland and rare salivary carcinomas may arise within an intraparotid lymph node. Some tumors, such as acinic cell carcinoma frequently illicit a secondary lymphoid reaction [9]. In addition, intraparotid lymph nodes are a routine location for metastatic disease, particularly arising from scalp tumors. This report describes, for the first time, an entirely intranodal low-grade intraductal carcinoma (so-called low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma) and explores the differential diagnosis and current state of knowledge of intraductal lesions of salivary gland.

Methods

H&E and immunohistochemical stains were performed on 4 μm thick unstained sections cut from representative formalin fixed paraffin embedded blocks. The immunohistochemistry was performed by the avidin–biotin-peroxidase complex technique. All stains were performed using commercially available antibodies in a Ventana® XT instrument (Ventana Systems, Tucson AZ) except androgen receptors (AR). The stains, sources and dilutions included AE1/AE3 (Dako; 1/800), S100 (Ventana, prediluted), BRST-2 (ID Labs, 1/400), AR (Biogenex, 1/800), p63 (Vector, 1/50), CK14 (Vector, 1/100), SMA (Ventana, prediluted), MSA (Dako, 1/100), calponin (Dako, 1/100) and MIB-1 (Dako, 1/100).

Results

Clinical and Pathological Findings

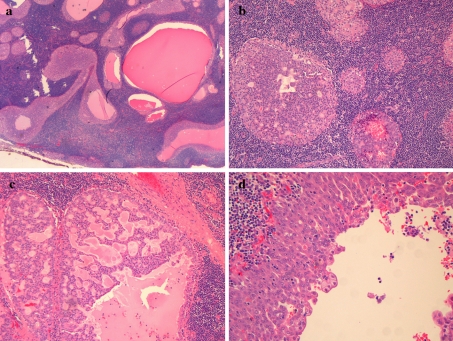

The patient was a 59-year-old female with a left parotid mass. The mass was 3.5 cm in size and showed a multicystic appearance with a reddish brown color and dark hemorrhagic cystic contents. Microscopically the lesion was circumscribed and appeared entirely intranodal. This was interpreted as a true lymph node as apposed to a lymphoid reaction to the tumor, as it contained a capsule as well as subcapsular and medullary sinuses. The tumor was evenly distributed throughout the node and consisted of back-to-back nests and cystic spaces of varying size (Fig. 1a). The nests showed both solid and cribriform architecture (Fig. 1b–c). The cystic spaces showed varying architecture including a single cell lining, multilayered cellular proliferations with micropapillary structures (Fig. 1d) and “Roman-bridges”. The cysts contained eosinophilic debris with macrophages, but no tumor necrosis was present. The cells showed low-grade simple ovoid to round nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli and no pleomorphism. No mitotic activity was identified. The cytoplasm varied from granular and amphophilic to focally oncocytic. The oncocytic areas were solid and lacked the bilayered lining typically seen in a Warthin tumor. There were bubbly microvacuoles present, particularly at the surface of the cells lining the cystic spaces. Some cells also had intracellular hemosiderin deposition. Isolated psammoma bodies were also noted. There were no areas showing an infiltrative pattern, desmoplasia or other stromal reactions, however the hilum of the node showed tumor nests surrounded by non-lymphoid stroma. No basophilic granules were noted in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells.

Fig. 1.

a Low power view of an intraductal carcinoma/low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma showing nodal location of back-to-back nests of tumor b–d. Higher power showing bland cells organized into varying patterns, including solid, cribriform and cystic spaces

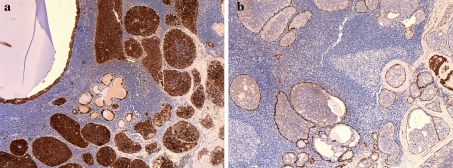

The tumor was diffusely positive for AE1/AE3 and S100 (Fig. 2a). Focal BRST-2 and AR staining was present and corresponded to the oncocytic elements, but the tumor was largely negative for these markers. The tumor nests were entirely surrounded by a thin non-neoplastic myoepithelial layer that stained with p63, CK14, SMA, MSA and calponin (Fig. 2b). This was true for all tumor nests including those in the nodal hilum. These markers did not stain the tumor cells themselves. The neoplasm was an entirely in situ process and represented an intraductal carcinoma (low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma) arising within an intraparotid lymph node.

Fig. 2.

a The tumor was diffusely positive for S100. b. A complete rim of non-neoplastic myoepithelial cells was noted surrounding all epithelial structures within the lymph node with antibodies to p63, CK14, SMA, MSA and calponin. Calponin is shown here. The tumor cells did not stain with these markers

Discussion

This is the first reported case of an intraductal carcinoma, or so-called low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma (IDC/LGCCC) arising within an intraparotid lymph node. The tumor grossly had the appearance of a Warthin tumor with a reddish-brown multicystic cut surface and dark hemorrhagic like cystic contents. Similarly, the microscopic appearance was initially reminiscent of Warthin tumor except that the majority of the tumor was amphophilic rather than oncocytic. In addition, the tumor nests varied from cribriform to solid and the cystic spaces showed a more complex pattern with micropapillary structures and “Roman-bridge” type architecture. Transformation of a Warthin tumor to an intraductal carcinoma or a benign metaplastic Warthin tumor were initially considered possibilities, however the tumor did not contain typical Warthin tumor-like elements which normally show a bilayering of cells with oncocytic features. The oncocytic nests in this tumor were solid rather than forming lumina and were only focal. The entire tumor was also S100 positive, which is a finding not seen in oncocytic tumors [10] including Warthin tumors. The tumor cells were negative for p63, whereas Warthin tumors usually have basally oriented p63 positive neoplastic cells. These are unlike the non-neoplastic myoepithelial cells that were seen surrounding this tumor, which were only appreciated by immunohistochemistry for p63, CK14, SMA, MSA and calponin. Warthin tumors do not have a true myoepithelial layer surrounding the tumor nests.

The presence of a non-neoplastic myoepithelial layer around all neoplastic nests helps rule out a metastatic non-salivary carcinoma and suggests that this tumor arose within salivary ductal inclusions that are typical of intraparotid lymph nodes. It also helps to exclude a metastatic or invasive IDC/LGCCC, which is important as about 10–25% of these tumors may show microinvasion [2, 3] and one case has shown transformation to a high-grade carcinoma with lymph node metastases [8]. Other salivary gland carcinomas may enter the differential diagnosis of this tumor as well. Cystadenocarcinoma, NOS, is a nebulous tumor with a similar tendency for cystic growth, but usually lacks the solid and cribriform architecture of IDC/LGCCC. It is generally S100 negative and lacks an investing myoepithelial layer [7]. Acinic cell carcinoma may arise in a lymph node and shows similar microvacuoles, granular cytoplasm and may occasionally contain papillary-cystic architecture. However, acinic cell carcinoma is generally negative for S100 [11], shows at least some basophilic granules and does not contain an intraductal component.

Recently, Skalova et al. described a new entity in the salivary gland named mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC), which shows a similar microvacuolar appearance to IDC/LGCCC and may have any of solid, cystic and papillary architecture. Importantly they are typically S100 positive as well. This possibly represents the most difficult differential diagnosis for the current tumor. Although no cases of MASC with an intraductal growth pattern have been described, it should be noted that only one IDC/LGCCC was included in the control group tested for the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion in Skalova et al’s original description of MASC [11]. In addition, secretory carcinoma of the breast with an intraductal component has been reported [12], however without molecular confirmation. For now, the presence of a complete myoepithelial layer around tumor nests is considered specific to IDC/LGCCC amongst salivary carcinomas [2, 3, 5, 8], and is the preferred diagnosis for this tumor. MASC in my experience also shows larger nests and solid growth than IDC/LGCCC and does not show “Roman-bridge” architecture. That being said, a larger study of ETV6-NTRK3 fusion in IDC/LGCCC seems warranted owing to the morphologic overlap between these tumors.

Since the first descriptions of IDC/LGCCC as “intraductal carcinoma” by Chen in 1983 [1] and “low grade salivary duct carcinoma” by Delgado et al. in 1996 [2], there have been several dozen cases of these and similar tumors described [3, 4, 7, 8]. While it is not clear that they are related, there have also been tumors with similar morphology labeled “salivary duct carcinoma in situ” in the literature [4]. Currently the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies these tumors as a variant of cystadenocarcinoma, which has generated some controversy, with some authors still believing that they represent a ductal tumor [8, 13]. Wayne et al. compared IDC to cystadenocarcinoma, NOS, in abstract form at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology’s (USCAP) annual meeting and found some overlap between these tumors and concluded that they were more closely related to eachother than to conventional salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) [7]. Simpson et al. on the other hand found 3 high-grade carcinoma in situ cases that overlapped morphologically with SDC to a considerable extent and were AR positive with one case having Her-2-Neu amplification by FISH [4]. In addition, a large percentage of conventional SDC cases have foci that appear to be surrounded by a myoepithelial layer [14], suggesting a pre-existing in situ component or secondary intraductal growth for some tumors.

It is not entirely clear at this point whether IDC/LGCCC is related to cystadenocarcinomas or to SDC or neither. It is not even clear to this author that all the reported cases are even related to eachother. Some are distinctly apocrine and these cases stain for AR and BRST-2 and are often S100 negative [4, 6, 8, 15]. Others are non-apocrine and these cases are generally negative for AR and always S100 positive [2, 3, 7]. In addition, we previously noted that almost all the cases reported in minor salivary gland showed intermediate or high-grade dysplasia, while most of the low-grade variants are located in the major salivary glands [8]. It is difficult to adequately compare these lesions to cystadenocarcinomas and SDC, when it is not clear that they are a uniform entity themselves. Another unaddressed question is the relationship of apocrine IDC/LGCCCs to polycystic sclerosing adenosis; another lesion with apocrine differentiation, which is known to be a clonal neoplasm [16] and may show in situ malignant transformation [17]. A stricter stratification of a large number of these tumors with molecular comparison is required to answer these questions.

This report highlights another example of IDC/LGCCC, which is the first case to have a completely intranodal location. This raises several possible differential diagnostic possibilities. These include benign entities such as Warthin tumor, primary carcinomas of salivary gland that illicit a lymphoid response such as acinic cell carcinoma, as well as metastatic carcinomas to intraparotid lymph nodes. This diagnosis could easily be missed if not considered, as the non-neoplastic myoepithelial layer could not be appreciated without immunohistochemical staining. Some pure intranodal carcinomas of salivary gland, such as acinic cell carcinomas have been noted to have a better behavior than typical examples [9]. IDC/LGCCCs without invasion also have an excellent prognosis with no cases of mortality reported so far [8]. Presumably, an intraductal proliferation that is also confined to a lymph node should have an indolent course as long as completely excised. However, there is insufficient follow up in this case, or understanding of IDC/LGCCC in general, to make predictions on behavior of this tumor or guide follow up or management at this time.

References

- 1.Chen KT. Intraductal carcinoma of the minor salivary gland. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97(2):189–191. doi: 10.1017/S002221510009397X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado R, Klimstra D, Albores-Saavedra J. Low grade salivary duct carcinoma. A distinctive variant with a low grade histology and a predominant intraductal growth pattern. Cancer. 1996;78(5):958–967. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<958::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandwein-Gensler M, Hille J, Wang BY, Urken M, Gordon R, Wang LJ, Simpson, Simpson RH, Gnepp Low-grade salivary duct carcinoma: description of 16 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(8):1040–1044. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000128662.66321.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson RH, Desai S, Di Palma S. Salivary duct carcinoma in situ of the parotid gland. Histopathology. 2008;53(4):416–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandwein-Gensler MS, Gnepp DR. Low Grade Cribriform Cystadenocarcinoma. In: World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (Eds.), IARC Press; Lyon. 2005. p. 223.

- 6.Arai A, Taki M, Mimaki S, Ueda M, Hori S. Low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36(6):725–728. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wayne S, Barnes EL, Seethala RR. Low grade intraductal carcinoma: a relative of cystadenocarcinoma, precursor to salivary duct carcinoma, or both? March: Presented in abstract form at the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology’s annual conference; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinreb I, Tabanda-Lichauco R, Kwast T, Perez-Ordonez B. Low-grade intraductal carcinoma of salivary gland: report of 3 cases with marked apocrine differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(8):1014–1021. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis G, Simpson RH. Acinic cell carcinoma. In: World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (Eds.), IARC Press, Lyon. 2005. p. 216–218.

- 10.Thompson LD, Wenig BM, Ellis GL. Oncocytomas of the submandibular gland. A series of 22 cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1996;78(11):2281–2287. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961201)78:11<2281::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, Starek I, Geierova M, Simpson RH, Passador-Santos F, Ryska A, Leivo I, Kinkor Z, Michal M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celik A, Kutun S, Pak I, Seki A, Cetin A. Secretory breast carcinoma with extensive intraductal component: case report. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2004;28(5–6):361–363. doi: 10.1080/019131290882367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheuk W, Chan JK. Advances in salivary gland pathology. Histopathology. 2007;51(1):1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araujo VC, Kowalski LP, Soares F, Araujo NS, Loducca SV, Sobral AP. Salivary duct carcinoma: cytokeratin 14 as a marker of in situ intraductal growth. Histopathology. 2002;41(3):244–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusafuka K, Itoh H, Sugiyama C, Nakajima T. Low-grade salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland: report of a case with immunohistochemical analysis. Med Mol Morphol. 2010;43(3):178–184. doi: 10.1007/s00795-009-0479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skálová A, Gnepp DR, Simpson RH, Lewis JE, Janssen D, Sima R, Vanecek T, Di Palma S, Michal M. Clonal nature of sclerosing polycystic adenosis of salivary glands demonstrated by using the polymorphism of the human androgen receptor (HUMARA) locus as a marker. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(8):939–944. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulciniti F, Losito NS, Ionna F, Longo F, Aversa C, Botti G, Foschini MP. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland: report of one case diagnosed by fine-needle cytology with in situ malignant transformation. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38(5):368–373. doi: 10.1002/dc.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]