Abstract

Focal osseous dysplasia (FOD) is one of the benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaw bones and the most commonly occuring benign fibro-osseous lesion. This entity occurs more commonly in females and has a predilection for African Americans. Radiographically, the lesion has a variable appearance depending on the duration but may appear as a radiolucent to radiopaque lesion that can be well to poorly defined. Hisotologically, when biopsied, there are fragments of bony trabeculae intermixed with fibrous stroma with incomplete stromal vasculature. The main differential diagnosis is with ossifying fibroma, which is neoplastic while FOD is considered a reactive process. Most patients with FOD may be followed clinically without surgical intervention.

Keywords: Osseous dysplasia, Focal osseous dysplasia, Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia, Benign fibro-osseous lesions, Jaw

History

A 43-year-old male had a history of an incidentally identified lesion in the posterior mandible. Over time, the lesion became more radiopaque, as observed during routine radiographic follow-up examinations.

Radiographic Features

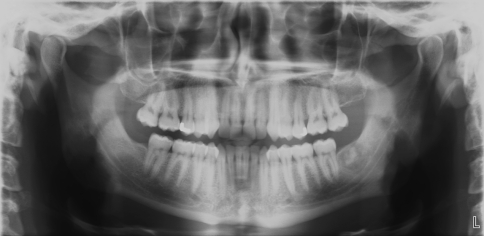

Panorex view of the oral cavity showed a non-expansile, mixed radiolucent-radiopaque, moderately well-defined lesion in the posterior mandible distal to the #18 tooth (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A non-expansile, mixed radiolucent-radiodense lesion in the posterior mandible, distal to tooth #18

Diagnosis

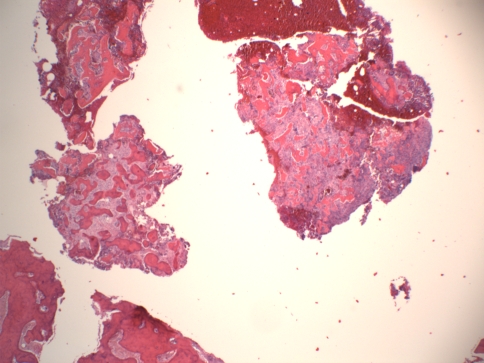

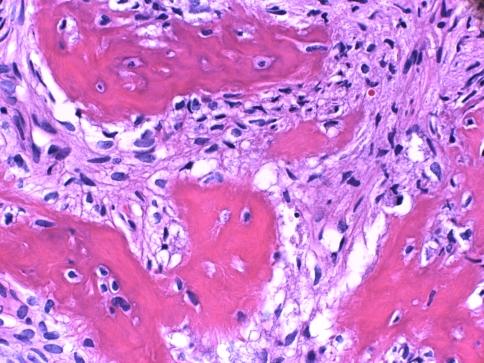

Grossly, the resected surgical specimen presented as multiple gritty fragments of tan-brown hemorrhagic tissue. Histologic examination on low magnification showed multiple fragments of curvilinear woven bone with intervening moderately cellular fibroblastic stroma in roughly equal proportions and scattered hemorrhagic foci (Fig. 2). Higher magnification revealed thick bony trabeculae without osteoblastic or cementoblastic rimming. There were no foci of inflammation. The stromal fibroblastic spindle cells were loosely arranged with oval nuclei and eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Fragments of curvilinear woven bone with intervening fibroblastic stroma and hemorrhagic foci

Fig. 3.

Thick bony trabeculae with intervening loosely arranged stromal fibroblastic spindle cells. There is no osteoblastic or cementoblastic rimming of the trabeculae

Discussion

Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaw encompass a range of clinicopathologic entities, a select few of which can be differentiated by histopathology alone. Knowledge of clinical and radiographic information in conjunction with histopathology is exceedingly important for accurate distinction. As the name implies, fibro-osseous lesions are benign entities possessing both fibrous and ossesous components, and include reactive, neoplastic, and dysplastic processes [1, 2]. Focal osseous dysplasia (FOD), also known as focal cemento-osseous dyplasia, represents the most common benign fibro-osseous lesion of the jaw, and includes periapical cemento-osseous dyplasia under the umbrella term [1, 3, 4]. FOD typically presents as a focal, asymptomatic lesion diagnosed incidentally on routine radiography, predominantly in a single quadrant in the mandible, although multiple lesions can occur within the same quadrant [1, 3–5]. When symptomatic, the lesions most commonly cause pain and swelling [1, 3–5]. Occasionally, FOD can lead to secondary pulpal and periodontal infection and progress to necrosis [6]. Adjacent teeth are typically spared [3, 5, 6]. FOD predominantly affects females with a mean age of 38 years, with a greater propensity in African Americans [2, 4, 5]. While the exact etiology of FOD is unclear, they are favored to arise from medullary bone and/or periodontal ligament tissue [6]. Hormonal imbalances affecting bone remodeling are currently being investigated [5].

Radiographically, the differential diagnosis includes periapical abscesses, focal sclerosing osteomyelitis, ossifying fibromas, granulomas, pulpal necrosis, and cysts [4–7]. The broad differential is in part due to the fact that FOD can appear differently based on the chronicity of the lesion [1, 3–5]. An early stage FOD lesion presents as a well- to poorly-defined radiolucent focus [1, 3–5]. The intermediate stage appears as a sclerotic radiodensity with ill-defined borders, with increasing opacity in the late stages as the lesion persists [1, 3, 5]. Additionally, lesions tend to be small and focal, averaging 1.5–1.8 cm or less, helping to distinguish them from florid cemento-osseous dysplasia, which affects multiple quadrants, and neoplastic ossifying fibromas, which average 3.8 cm in size [2, 4]. A key feature of FOD is its association with the periapex as well as previous extraction sites [2, 4–6]. And unlike ossifying fibromas, focal osseous dyplasia is not associated with expansion of the jaw nor displacement of the teeth [1, 3, 4, 7].

Grossly, FOD is received as fragments of tan, gritty, friable tissue from currettings; hemorrhage is often diffusely present [1, 5, 8]. Histopathologic features show fragments of woven or lamellar bone with cementum-like material in a meshwork of spindled stroma composed of fibroblasts, loose collagen fibers, and small vessels [2, 8]. Vessels in FOD are dilated, irregular, and closely associated with the bony trabeculae, with an interrupted endothelium [8]. Microscopic findings parallel radiography, with older lesions exhibiting increased amounts of cementum-like material and calcifications [1, 6, 8]. The thick, curvilinear trabeculae frequently found in the intermediate stages have been described as a “ginger root pattern,” [1, 8].

The main histopathologic differential diagnoses for FOD includes focal sclerosing osteomyelitis and ossifying fibroma [6]. Unlike the aforementioned histopathologic findings of FOD, focal sclerosing osteomyelitis consists of fibrous tissue with an increased inflammatory component and mineralization without cementum-like calcifications [6]. The intermediate stage of FOD is most frequently confused with ossifying fibroma because of the presence of osteoblasts and osteoclasts near the bony trabeculae [2, 8]. However, ossifying fibroma is infrequently received as fragments; instead, it shells out more easily as a result of being encapsulated and well-circumscribed, thus making the lesion more amenable to enucleation or block resection [1, 8]. In addition, ossifying fibromas possess a denser fibroblastic stroma, and frequently, a storiform architecture [6]. Moreover, bony portions are rimmed by osteoblasts or cementoblasts, and the endothelial layer of the vasculature is continuous [1–3, 6, 8]. Hemorrhage is unusual and localized at the periphery versus a diffuse pattern seen in FOD [2, 8].

Treatment of asymptomatic FOD consists of radiographic follow-up to monitor for progression, which, when present, would be worrisome for ossifying fibroma [1, 3]. Rarely, FOD may progress to florid cemento-osseous dyplasia [6]. Biopsy is recommended when lesions become symptomatic, show radiological features concerning for ossifying fibroma, or occur at a site that will be used for an implant [5]. Surgical exploration and biopsy are generally reserved for symptomatic lesions [2, 3].

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

Contributor Information

Evelyn M. Potochny, Phone: +619-379-2001, FAX: +619-532-9403, Email: evelyn.potochny@med.navy.mil

Aaron R. Huber, Phone: +619-532-9440, FAX: +619-532-9403, Email: aaron.huber@med.navy.mil

References

- 1.Eversole R, Su L, ElMofty S. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the Craniofacial complex: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:177–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi A. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. In: Neville B, Damm D, Allen M, Bouquot J, editors. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3. Elsevier: Saunders; 2009. pp. 635–648. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholl JR, Kellet HM, et al. Cysts and cystic lesions of the mandible: clinical and radiologic-histopathologic review. Radiographics. 1999;19(5):1107–1124. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se021107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su L, Weather DR, Waldron CA. Distinguishing features of focal cemento-osseous dysplasia and cemento-ossifying fibromas. A clinical and radiologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84(5):540–549. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:350–360. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/31641295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drazic R, Minic AJ. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia in the maxilla mimicking periapical granuloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1999;88(1):87–89. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Hiranuma H, et al. Cemento-osseous dysplasia of the jaws in 54 Japanese patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su L, Weathers DR, Waldron CA. Distinguishing features of focal cemento-osseous dysplasia and cemento-ossifying fibromas: a pathologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84(3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]