Abstract

A new method is reported for effecting catalytic enantioselective intramolecular [5+2] cycloadditions based on oxidopyrylium intermediates. The dual catalyst system consists of a chiral primary aminothiourea and a second achiral thiourea. Experimental evidence points to a new type of cooperative catalysis with each species being necessary to generate a reactive pyrylium ion pair which undergoes subsequent cycloaddition with high enantioselectivity.

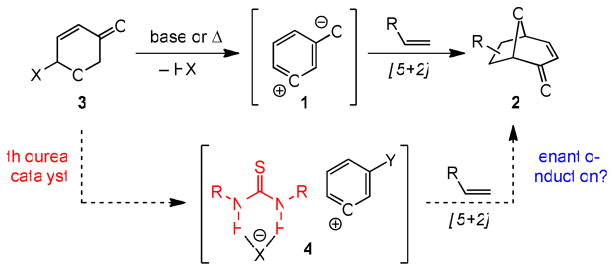

The [5+2] dipolar cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ylides (1, Scheme 1) and two-carbon dipolarophiles generates complex, chiral 8-oxabicyclo[3.2.1]octane architectures 2.1 In addition to being a structural motif common to numerous natural products,2 such cycloadducts have proven to be highly valuable intermediates in the synthesis of functionalized seven-membered carbocycles3 and tetrahydrofuran derivatives.4 Despite the utility of this [5+2] cycloaddition and its widespread use in organic synthesis,5 asymmetric examples have thus far been limited to diastereoselective variants,6 and there are currently no catalytic enantioselective methods that engage reactive pyrylium intermediates in cycloaddition chemistry.7 Herein we report a dual-catalyst system consisting of a chiral primary aminothiourea and an achiral thiourea that promotes an intramolecular variant of the title reaction with high enantioselectivity. Experimental evidence points to a new type of cooperative mechanism of catalysis.8

Scheme 1.

Oxidopyrylium cycloadditions and proposed mode of catalysis

It has been shown recently that small-molecule chiral hydrogen-bond donor catalysts can serve as anion abstractors and binders in the generation and enantioselective transformation of highly reactive cationic intermediates,9 and we became interested in the potential application of the principle of anion-binding catalysis to oxidopyrylium formation and cycloaddition. These intermediates are generally accessed by thermolysis of the corresponding acetoxypyranone 3 (X = OAc, Scheme 1),10 or by reaction of 3 with an amine base.11 Upon elimination of acetic acid, reactive 1 has been shown to undergo [5+2] cycloadditions with both electron-rich and electron-poor dipolarophiles.12 We hypothesized that a urea or thiourea catalyst might induce ionization of an appropriate leaving group from 3 or a tautomeric form thereof, to give pyrylium 4. Our efforts thus focused on identifying an appropriate precursor to this species (i.e. X in 3) as well as the best mode for activation and asymmetric induction in subsequent [5+2] cyloadditions.

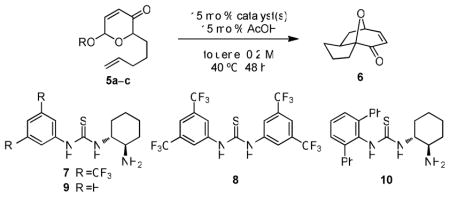

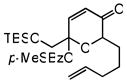

Racemic acetoxypyranone 5a11 was chosen for initial exploratory and ensuing optimization studies. The desired reaction was found to take place in the presence of a variety of chiral thiourea derivatives in combination with stoichiometric triethylamine, but no stereoinduction was observed in the formation of cycloadduct 6.13 In contrast, bifunctional primary aminothiourea 714 induced formation of 6 with low levels of enantioselectivity in the absence of exogenous base (Table 1, entry 1). An unexpected but ultimately significant observation resulted from a broad screen of additives, with achiral thiourea catalyst 815 dramatically improving the reaction enantioselectivity (entry 2). The addition of acetic acid as a second co-catalyst provided a measurable yield enhancement, with no effect on product ee (entry 3). Other achiral or chiral hydrogen-bond donors (including the urea analogue of 8) proved less beneficial as additives. Whereas the electron-poor bistrifluoromethyl anilide group is found to be an optimal chiral catalyst feature in a growing number of enantioselective thiourea-promoted reactions,16 phenylthiourea 9 (entry 4) was found to be comparable to 7. This prompted an exhaustive examination of the effect of aryl substitution on the aminothiourea catalyst,13 and led to the identification of 10, which bears a 2,6-diphenylanilide component, as the most enantioselective aminothiourea catalyst (entry 5). The diminished reactivity displayed by 10 was overcome by utilizing substrate 5b containing a benzoate-leaving group (entry 6). Upon exploring various substituents on the benzoate a further enhancement was observed with para-thiomethylbenzoyl substrate 5c (entry 7). This improved reactivity is likely not a result of better leaving group or hydrogen-bond accepting ability, as para-thiomethyl substitution has no effect on the acidity of benzoic acid (σpara = 0.017). This effect may instead be a result of the lower solubility in toluene of the para-thiomethylbenzoic acid byproduct (as compared to benzoic or acetic acid), which precipitates during the course of the reaction. Finally, increasing the reaction concentration further improved the rate, allowing for the loadings of 10 and 8 to be reduced with this parent substrate (entry 8).

Table 1.

Reaction optimization

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate (R=) | catalyst(s) | yield (%)a | ee (%)b |

| 1c | 5a (Ac) | 7 | 37 | 21 |

| 2c | 5a (Ac) | 7 + 8 | 44 | 67 |

| 3 | 5a (Ac) | 7 + 8 | 53 | 67 |

| 4 | 5a (Ac) | 9 + 8 | 41 | 66 |

| 5 | 5a (Ac) | 10 + 8 | 30 | 88 |

| 6 | 5b (Bz) | 10 + 8 | 56 | 91 |

| 7 | 5c (p-MeSBz) | 10 + 8 | 72 | 91 |

| 8d | 5c (p-MeSBz) | 10 + 8 | 76 | 91 |

Reactions performed on a 0.05 mmol scale.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Determined by HPLC using commercial chiral columns.

No added AcOH.

Conditions: 10 mol% 10 + 8, 0.4 M.

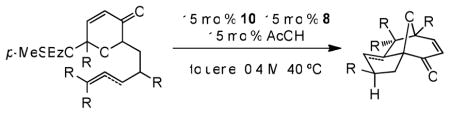

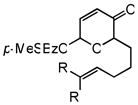

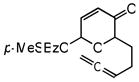

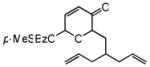

With optimal catalytic conditions in hand, an examination of the substrate scope was undertaken (Table 2). Substitutions at the olefin terminus were tolerated (entries 2–7), despite a diminishment of reactivity occurring upon increased substitution (entries 4 and 7). Allenes are viable cycloaddition substrates (entries 8 and 9), however alkyne-bearing substrates proved unreactive under the current set of conditions. Other viable substrates include those bearing substitution on the tether connecting the dipole and dipolarophile as in diallyl substrate 27 (entry 10), or on the pyranone ring as in 29 (entry 11). Product 30 bears a siloxymethylene unit commonly found in synthetically useful oxidopyrylium cycloadducts. 18 Substrate variations that were not tolerated include methylation at the internal position of the olefin as well as a homologue of substrate 5c containing an additional methylene in the tether. Initial efforts to extend this system to an asymmetric intermolecular variant have been met with only moderate success.13

Table 2.

Substrate scope

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | time (h) | yield (%)a | ee (%)b |

| 1c,d |

5c |

6 |

48 | 74 | 91 |

| 2 |

11 R=Me R′=H |

12 | 72 | 70 | 90 |

| 3 |

13 R=H R′=Me |

14 | 72 | 66 | 89 |

| 4 |

15 R=Me R′=Me |

16 | 96 | 51 | 89 |

| 5 |

17 R=H R′=Ph |

18 | 72 | 48 | 86 |

| 6 |

19 R=CO2Et R′=H |

20 | 72 | 66 | 90 |

| 7e |

21 R=CO2Me R′=Me |

22 | 96 | 37 | 80 |

| 8c,d |

23 |

24 |

72 | 54 | 95 |

| 9 |

25 |

26 |

72 | 42 | 88 |

| 10d |

27 |

28 |

72 | 77 | 90 |

| 11 |

29 |

30 |

72 | 70f | 89f |

Isolated yields after chromatography on silica gel.

Determined by HPLC using commercial chiral columns.

10 mol% 10 + 8.

The absolute stereochemistry of 24 and derivatives of 28 and 6 were determined by Xray crystallography and that of all other products was assigned by analogy.

20 mol% 10 + 8.

Determined on the free alcohol.

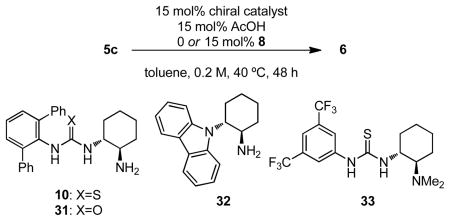

In order to probe the possible roles of the different components in this dual thiourea catalyst system, a series of reactions were run with different bifunctional chiral catalysts in the presence and absence of 8 (Table 3). A clear and dramatic cooperative effect is observed between the optimal catalysts as evidenced by the poorer results obtained without achiral catalyst 8 (entry 1). A beneficial effect of 8 has also been reported recently in proline-catalyzed transformations, where its primary role appears to be as a phasetransfer catalyst to solubilize proline in the non-polar media.19 Such a role is unlikely in the present system, as all components of this oxidopyrylium-based cycloaddition reaction are initially soluble in toluene (vide supra).

Table 3.

Catalyst structure-activity relationship study

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | 0 mol% 8 | 15 mol% 8 | ||

| yield (%)a | ee (%)b | yield (%)a | ee (%)b | ||

| 1 | 10 | 32 | 72 | 72 | 91 |

| 2 | 31 | 7 | n.d. | 58 | 71 |

| 3 | 32 | 7 | n.d. | 58 | −85 |

| 4 | 33 | 10 | n.d. | 11 | n.d. |

Reactions performed on a 0.05 mmol scale.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Determined by HPLC using commercial chiral columns.

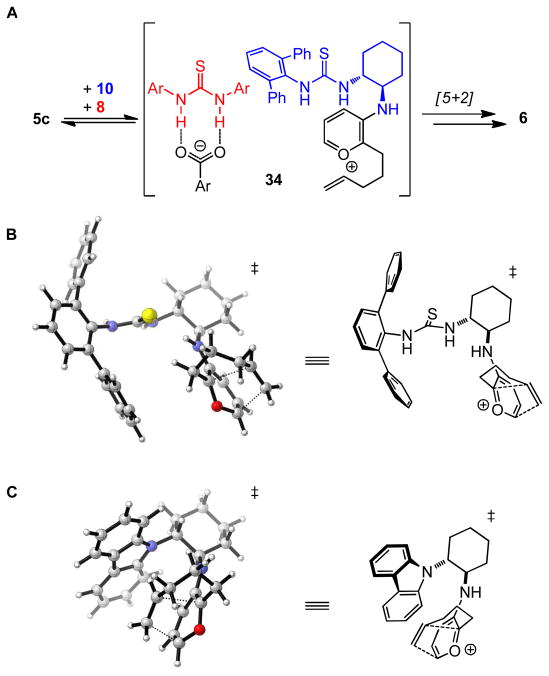

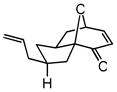

Instead, we propose that the function of 8 in the pyrylium cycloaddition reaction is as a carboxylate-binding agent (Figure 1A), acting cooperatively with 10 to generate the reactive ion pair 34. Compound 31, the urea analog of 10, displays very low reactivity in the absence of 8,20 but does serve as a moderately enantioselective co-catalyst in conjunction with 8 (Table 3, entry 2). While the thiourea component of the optimal catalyst 10 therefore does influence the reaction enantioselectivity even in the presence of 8 (compare entries 1 and 2), it is not necessary for obtaining reactivity or high ee. Thus, the combination of primary aminocarbazole 32 and thiourea 8 is an effective catalyst system, catalyzing the selective formation of 6 in 85% ee (entry 3). It is significant that catalysts 10 and 32 induce cycloaddition with opposite senses of enantiocontrol (vide infra). Consistent with the notion that an H-bond donor catalyst is needed to induce ionization to the pyrylium ion, primary aminocarbazole 32 is virtually unreactive in the absence of 8 (entry 3). Tertiary aminothiourea 3321 is unreactive both in the presence and absence of 8 (entry 4), pointing to the necessity of a primary amine for catalytic activity. These observations with basic tertiary aminothiourea 33 as well as the fact that acetic acid increases the rate of reaction are consistent with an operative enamine catalysis mechanism. Condensation between the amine of the catalyst and the ketone of the substrate is expected to yield a dienamine after tautomerization. Hydrogen-bond donor-mediated benzoate abstraction would then generate a catalyst •pyrylium adduct 34 poised to undergo the intramolecular cycloaddition.

Figure 1.

(A) Proposed role for thiourea catalysts 10 and 8. Calculated lowest energy cycloaddition transition structures at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory for (B) 10•pyrylium, and (C) 32•pyrylium.

With the goal of evaluating the viability of aminopyrylium 34 in the cycloaddition chemistry induced by the catalyst combination of 10 and 8, a computational frontier molecular orbital analysis22 of a variety of dipolarophiles and of oxido-, amido-, and aminopyryliums (4, Y = O−, NH−, NH2, respectively, Scheme 1) was performed and compared with observed trends in intermolecular cycloadditions. The dominant HOMO-LUMO interactions between each of the three hypothetical pyrylium species and alkenes of varying electronic properties were thereby predicted.13 With an oxido- or amidopyrylium, either the HOMO or the LUMO of the dipole can be more relevant to cycloaddition depending on the dipolarophile, in line with the experimental observation that oxidopyrylium dipolar intermediates undergo reaction with either electron-rich or electron-deficient alkenes.5c,12 Alternatively, the LUMO of an aminopyrylium was predicted to be the MO relevant to cycloaddition in all cases, consistent with our observation that intermolecular reactions under thiourea-catalyzed conditions only proceed with electron-rich dipolarophiles containing a high HOMO.13 The results thus point towards an aminopyrylium – and not an oxido- or amidopyrylium – as the relevant intermediate in the thiourea-catalyzed reactions described herein.

While the unprecedented intermediacy of aminopyryliums such as 34 agrees with the experimental and computational data described above, the reversal in the sense of enantioinduction observed using primary amine catalysts 10 and 32 in conjunction with achiral thiourea 8 was difficult to reconcile by any simple means. A computational analysis of transition structures for cycloadditions of the proposed 10•pyrylium and 32•pyrylium ions was therefore undertaken.23 Although these simplified models do not take into account the counteranion, good correlation with experimental results were obtained. Of the multiple first-order saddle points that were located for each complex, the lowest energy transition structure leads to the observed major enantiomer of product (Figure 1B,C), and the second-lowest energy transition structure corresponds to the observed minor enantiomer in each case.24

In summary, we have identified a dual thiourea catalyst system for intramolecular oxidopyrylium [5+2] cycloadditions, providing enantioselective access to valuable tricyclic structures. Application of this reaction to the synthesis of biologically active small-molecules, further mechanistic studies into the origin of the catalyst cooperativity, and extension of the underlying principles to other multifunctional (thio)urea-catalyzed transformations are the focus of ongoing investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (GM43214), by an NDSEG predoctoral fellowship to M.R.W. (32CFR168a), and by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship to N.Z.B. (GM089036). We thank Dr. Shao-Liang Zheng for crystal structure determination and Dr. Christopher Uyeda for the synthesis and use of catalyst 32. Figures 1B and 1C were generated using CYLview.25

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Full experimental procedures, syntheses of substrates and catalysts 10 and 32, characterization data for all new compounds, NMR spectra for cycloaddition products, HPLC traces for scalemic cycloaddition products, geometries and energies of calculated stationary points, and crystallographic information. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Recent reviews: Singh V, Krishna UM, Vikrant, Trivedi GK. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:3405–3428.Pellissier H. Adv Synth Cat. 2011;353:189–218.

- 2.For example, Englerin A: Ratnayake R, Covell D, Ransom TT, Gustafson KR, Beutler JA. Org Lett. 2009;11:57–60. doi: 10.1021/ol802339w.Intricarene: Marrero J, Rodríguez AD, Barnes CL. Org Lett. 2005;7:1877–1880. doi: 10.1021/ol0505961.Komaroviquinone: Uchiyama N, Kiuchi F, Ito M, Honda G, Takeda Y, Khodzhimatov OK, Ashurmetov OA. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:128–131. doi: 10.1021/np020308z.Descurainin: Sun K, Li X, Li W, Wang J, Liu J, Sha Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 2004;52:1483–1486. doi: 10.1248/cpb.52.1483.Cartorimine: Yin HB, He ZS, Ye Y. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1164–1165. doi: 10.1021/np000140m.

- 3.(a) Wender PA, Lee HY, Wilhelm RS, Williams PD. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8954–8957. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bromidge SM, Sammes PG, Street LJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1985:1725–1730. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Fishwick CWG, Mitchell G, Pang PFW. Synlett. 2005:285–286. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krishna UM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2148–2150. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yadav AA, Sarang PS, Trivedi GK, Salunkhe MM. Synlett. 2007:989–991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Wender PA, Kogen H, Lee HY, Munger JD, Wilhelm RS, Williams PD. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:8957–8958. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wender PA, Jesudason CD, Nakahira H, Tamura N, Tebbe AL, Ueno Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:12976–12977. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ali MA, Bhogal N, Findlay JBC, Fishwick CWG. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5655–5658. doi: 10.1021/jm050533o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Roethle PA, Hernandez PT, Trauner D. Org Lett. 2006;8:5901–5904. doi: 10.1021/ol062581o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Li Y, Nawrat CC, Pattenden G, Winne JM. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:639–640. doi: 10.1039/b819454h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nicolaou KC, Kang Q, Ng SY, Chen DYK. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8219–8222. doi: 10.1021/ja102927n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Wender PA, Rice KD, Schnute ME. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7897–7898. [Google Scholar]; (b) López F, Castedo L, Mascareñas JL. Org Lett. 2000;2:1005–1007. doi: 10.1021/ol005724u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) López F, Castedo L, Mascareñas JL. Org Lett. 2002;4:3683–3685. doi: 10.1021/ol026633v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wender PA, Bi FC, Buschmann N, Gosselin F, Kan C, Kee JM, Ohmura H. Org Lett. 2006;8:5373–5376. doi: 10.1021/ol062234e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Garnier EC, Liebeskind LS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7449–7458. doi: 10.1021/ja800664v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For an isolated example of Rh-catalyzed benzopyrylium cycloadditions that proceed in low (<20%) enantioselectivity, see: Hodgson DM, Stupple PA, Johnstone C. ARKIVOC. 2003. pp. 49–58.Transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of carbonyl ylides to access similar products have been reported: Kitagaki S, Anada M, Kataoka O, Matsuno K, Umeda C, Watanabe N, Hashimoto S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:1417–1418.Hodgson DM, Labande AH, Pierard FYTM, Expósito Castro MÁ. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6153–6159. doi: 10.1021/jo0343735.Hodgson DM, Brückl T, Glen R, Labande AH, Selden DA, Dossetter AG, Redgrave AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5450–5454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307274101.Shimada N, Anada M, Nakamura S, Nambu H, Tsutsui H, Hashimoto S. Org Lett. 2008;10:3603–3606. doi: 10.1021/ol8013733.Ishida K, Kusama H, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8842–8843. doi: 10.1021/ja102391t.

- 8.A remarkable effect of TfNH2 on the enantio- and diastereoselectivity of rhodium-catalyzed cyclopropanations of α-cyano diazoacetamide has been noted by Charette and co-workers. The basis for this cooperative effect appears to be entirely different from the one described herein: Marcoux D, Azzi S, Charette AB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6970–6972. doi: 10.1021/ja902205f.

- 9.Raheem IT, Thiara PS, Peterson EA, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13404–13405. doi: 10.1021/ja076179w.Reisman SE, Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7198–7199. doi: 10.1021/ja801514m.Klausen RS, Jacobsen EN. Org Lett. 2009;11:887–890. doi: 10.1021/ol802887h.Zuend SJ, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15358–15374. doi: 10.1021/ja9058958.Xu H, Zuend SJ, Woll MG, Tao Y, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2010;327:986–990. doi: 10.1126/science.1182826.Knowles RR, Lin S, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5030–5032.Brown AR, Kuo WH, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9286–9288. doi: 10.1021/ja103618r.De CK, Klauber EG, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17060–17061. doi: 10.1021/ja9079435.For a recent review, see: Zhang Z, Schreiner PR. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1187–1198. doi: 10.1039/b801793j.

- 10.Hendrickson JB, Farina JS. J Org Chem. 1980;45:3359–3361. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Sammes PG, Street LJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1982:1056–1057. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sammes PG, Street LJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1983:1261–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sammes PG, Street LJ. J Chem Res, Synop. 1984:196–197. [Google Scholar]

- 13.See Supporting Information for details.

- 14.For preparation and use, see reference 9g and references therein.

- 15.(a) Schreiner PR, Wittkopp A. Org Lett. 2002;4:217–220. doi: 10.1021/ol017117s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wittkopp A, Schreiner PR. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:407–414. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For examples that include a direct comparison of different aryl thioureas, see: 9b, 9c, 9d, 9g, 9h, and 21.

- 17.McDaniel DH, Brown HC. J Org Chem. 1958;23:420–427. [Google Scholar]

- 18.See references 3a, 5b, 6a, and 6d for examples.

- 19.(a) Reis Ö, Eymur S, Reis B, Demir AS. Chem Commun. 2009:1088–1090. doi: 10.1039/b817474a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Companyó X, Valero G, Crovetto L, Moyano A, Rios R. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:6564–6568. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Demir AS, Eymur S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:112–115. [Google Scholar]; (d) Demir AS, Eymur S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- 20.In general, ureas are substantially weaker Brønsted acids than the corresponding thioureas, and accordingly also poorer H-bond donors: pKa of N,N′-diphenylthiourea (DMSO) = 13.5, while N,N′-diphenylurea = 19.5: Bordwell FG, Algrim DJ, Harrelson JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5903–5904.

- 21.Okino T, Hoashi Y, Takemoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12672–12673. doi: 10.1021/ja036972z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang G, Musgrave CB. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:1554–1561. doi: 10.1021/jp061633o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.B3LYP/6-31G(d) has been established as an appropriate level of theory for studying oxidopyrylium [5+2] cycloadditions: López F, Castedo L, Mascareñas JL. J Org Chem. 2003;68:9780–9786. doi: 10.1021/jo035259p.Wang SC, Tantillo DJ. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1516–1523. doi: 10.1021/jo7023762.

- 24.Uncorrected electronic energy differences between the two lowest energy diastereomeric transition structures are 1.31 kcal/mol for 10•pyrylium and 1.33 kcal/mol for 32•pyrylium. See Supporting Information for structures.

- 25.Legault CY. CYLview, 1.0b. Université de Sherbrooke; 2009. http://www.cylview.org. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.