Abstract

BACKGROUND

The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) found a higher risk of stroke after carotid artery stenting and a higher risk of myocardial infarction (MI) after carotid endarterectomy.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Cardiac biomarkers and ECGs were performed before and 6 to 8 hours after either procedure and if there was clinical evidence of ischemia. In CREST, MI was defined as biomarker elevation plus either chest pain or ECG evidence of ischemia. An additional category of biomarker elevation with neither chest pain nor ECG abnormality was prespecified (biomarker+ only). Crude mortality and risk-adjusted mortality for MI and biomarker+ only were assessed during follow-up. Among 2502 patients, 14 MIs occurred in carotid artery stenting and 28 MIs in carotid endarterectomy (hazard ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.26 to 0.94; P=0.032) with a median biomarker ratio of 40 times the upper limit of normal. An additional 8 carotid artery stenting and 12 carotid endarterectomy patients had biomarker+ only (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.27 to 1.61; P=0.36), and their median biomarker ratio was 14 times the upper limit of normal. Compared with patients without biomarker elevation, mortality was higher over 4 years for those with MI (hazard ratio, 3.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.67 to 6.92) or biomarker+ only (hazard ratio, 3.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.46 to 8.68). After adjustment for baseline risk factors, both MI and biomarker+ only remained independently associated with increased mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients randomized to carotid endarterectomy versus carotid artery stenting, both MI and biomarker+ only were more common with carotid endarterectomy. Although the levels of biomarker elevation were modest, both events were independently associated with increased future mortality and remain an important consideration in choosing the mode of carotid revascularization or medical therapy.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION INFORMATION

ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00004732

Keywords: Carotid arteries, carotid artery stenting, carotid endarterectomy, myocardial infarction, prognosis

Introduction

The recently published primary data from the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) showed no difference in the composite end point of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) or death during the periprocedural period and ipsilateral stroke over 4-years of follow-up.(1) However, the higher risk of stroke with carotid artery stenting (CAS) and the higher risk of periprocedural MI after carotid endarterectomy (CEA) underscore the need for detailed analysis of the individual components of the composite end point.(1) Indeed, it has been argued that MI in this setting is not as important an event in terms of overall health as stroke, and the previously presented quality-of-life data in CREST are concordant with this view.(1, 2) On the other hand, it has been shown that small elevations of cardiac enzymes after a variety of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular procedures are associated with increased future mortality.(3–15) Whether these findings pertain to patients undergoing carotid artery revascularization is unknown. We therefore performed a post hoc analysis to explore in detail the characteristics and prognostic importance of MI among patients undergoing either CAS or CEA.

Methods

One hundred eight centers in the United States and 9 in Canada enrolled 2502 patients in CREST, a randomized, controlled trial of CAS versus CEA with blinded end point adjudication.(16, 17) The institutional review boards/ethics committees at all participating centers approved the protocol and all patients gave written informed consent. Accunet and Acculink carotid stenting systems by Abbott Vascular Solutions (formerly Guidant), Santa Clara, CA, were used for patients randomized to CAS.

Patient Population

Symptomatic (stroke, transient ischemic attack or amaurosis fugax <180 days prior to randomization) and asymptomatic patients with qualifying stenosis severity were eligible for randomization to CAS or CEA. Full eligibility criteria are described elsewhere.(18) Patients assigned to CAS received aspirin and clopidogrel before and after the procedure, and those assigned to CEA received aspirin.(18) The primary study end point was the composite of any stroke, MI, or death during the periprocedural period, or ipsilateral stroke within 4 years after randomization. The definition of the periprocedural period and details of the statistical analysis have previously been presented.(1)

Ascertainment of Periprocedural Myocardial Infarction

Cardiac biomarkers were measured routinely before and 6–8 hours after the assigned study procedure. Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were performed prior to and 6–48 hours and 1 month after the procedure. Additional cardiac biomarkers and ECGs were recommended if there was evidence of pathological elevation of post-procedure biomarkers, a change in ECG, or chest pain lasting >15 minutes, or for other symptoms suggesting myocardial ischemia. Patients suspected of having an MI on the basis of symptoms or ECG changes were identified by the individual sites and referred for adjudication of possible MI. Adjudication was performed by two members of a three-person events review committee using original source documents. If the two reviews were discordant, a third review was performed and the event designation was assigned by the majority opinion. In addition, all preprocedural and postprocedural ECGs were reviewed by a centralized core laboratory and classified as demonstrating MI with a high or moderate likelihood. When MI was suspected on the basis of the ECG reading, serial ECGs were analyzed to determine whether the infarction represented a new event. Any ECG demonstrating a high or moderate likelihood of MI resulted in referral of the case to the adjudication committee which made the final determination of whether an MI occurred. Committee members were blinded to randomized treatment assignment. Screening of cardiac enzymes recorded in the trial database was performed, and cases in which elevated biomarkers were found were also sent for committee adjudication, as described below.

Cardiac biomarkers were analyzed at local-site laboratories, yielding a mixture of biomarkers and local-site laboratory MI designations. At sites that obtained troponin I, thresholds for detection varied from 0.03 to 0.1 ng/mL, and thresholds for MI designation ranged from 0.4 to 0.78 ng /mL. At sites using troponin T, the threshold for detection was 0.01 ng/mL and the threshold for MI designation was 0.10 ng/mL. At sites where creatine kinase (CK) was obtained, the upper limits of normal ranged from 122 to 200 IU/L, and the upper limits of normal for CK-MB (CK-MB) ranged from >5 ng/mL to 16 IU/L.

By protocol, MI required evidence of myocardial ischemia plus elevation of CK-MB or troponin to a value of ≥2 times the individual clinical center’s laboratory upper limit of normal.(18) Evidence of myocardial ischemia included chest pain or equivalent symptoms consistent with myocardial ischemia or ECG evidence of ischemia, including new ST-segment depression or elevation >1 mm in ≥2 contiguous leads or new pathological Q waves in ≥2 contiguous leads. In the absence of chest pain or ECG changes, suspected cases were sent for adjudication with troponin T ≥0.10 or troponin I >2 times the detection limit or with an upward trend at any quantitative level. Elevation of biomarkers without symptoms or ECG changes (biomarker+ only) was prespecified and defined as elevation of CK-MB or troponin to a value of ≥2 times the individual clinical center’s laboratory upper limit of normal in the absence of a coronary revascularization procedure. If percutaneous coronary intervention was performed, elevation of CK-MB or troponin to a value of ≥3 times the individual clinical center’s laboratory upper limit of normal was required. Finally, if coronary bypass surgery was performed, elevation of CK-MB or troponin to a value of ≥5 times the individual clinical center’s laboratory upper limit of normal was required. Per protocol, these events were not included in the primary end point but have been included in this analysis when indicated.

For estimation of MI size, we used the methodology of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Registry of acute coronary syndromes and computed a peak biomarker ratio(19, 20)and, when available, a CK-MB index (CK-MB/total CK) × 100).(21) For troponin I and CK-MB, the peak biomarker ratio was the highest level of the biomarker divided by the upper limit of normal of each site’s reference laboratory. For troponin T, the reference value was set at 0.01 ng/mL.

Although the study protocol did not prespecify criteria for the definition of ST-elevation, Q-wave, or non–ST-elevation MI, the event committee reviewers’ narratives were reviewed post hoc, along with ECGs and source documents by 1 reviewer blinded to randomization to CEA or CAS, and a designation of ST-elevation MI or non–ST-elevation MI was made.

Stroke was defined as an acute neurological event with focal symptoms and signs lasting ≥24 hours that were consistent with focal cerebral ischemia. The adjudication process was initiated after a clinically significant neurological event, any positive response on the transient ischemic attack–stroke questionnaire, or an increase by ≥2 points in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score. Stroke was defined as major stroke on the basis of clinical data or if the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was ≥9 at 90 days after the procedure. All other strokes were considered minor. Only ipsilateral stroke was adjudicated after the periprocedural period.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of this analysis, patients were characterized as MI, biomarker+ only, or neither MI nor biomarker+ only. Baseline characteristics were compared by use of the x2 test for discrete variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Comparison of biomarkers between groups was analyzed with a 2-tailed t test. Multivariable predictors of periprocedural MI and biomarker+ only were assessed with the following covariates: age, diabetes mellitus, previous cardiovascular disease or prior coronary artery bypass surgery, and creatinine clearance. Crude mortality and the hazard ratio for mortality up to 4 years were calculated and adjusted for baseline differences through the use of a Cox proportional hazards model incorporating the same 4 baseline covariates noted above.

Results

Overall, CREST randomized 2502 patients: 1240 assigned to CEA and 1262 to CAS. Cardiac biomarkers were collected before CEA or CAS in 90% of these patients and at 6 to 8 hours after the procedure in 88%; troponin without CK+CK-MB was obtained in 37%, troponin with CK+CK-MB in 23%, and CK+CK-MB without troponin in 30%. There were 42 patients with adjudicated MI in CREST. Fourteen MIs occurred among the CAS patients and 28 among the CEA patients (hazard ratio, 0.50; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26 to 0.94; P=0.032). Of these, 1 occurred after randomization but before the index procedure, 29 occurred within 24 hours of the initial carotid revascularization procedure, 9 occurred between 2 and 7 days after carotid revascularization, and 3 occurred between 8 and 30 days after carotid revascularization. Two ST-elevation MIs were detected, 1 after CAS and 1 after CEA. Twenty additional patients were adjudicated from 114 suspected MI events as having biomarker+ only (ie, without either chest pain or ECG changes); 12 events occurred in the CEA group and 8 in the CAS group (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.27 to 1.61; P=0.36). Of these 20 biomarker+ only events, 18 occurred within 24 hours of the initial carotid revascularization procedure, and 2 occurred between 2 and 7 days after carotid revascularization.

Baseline characteristics according to MI status are shown in Table 1. The MI or biomarker+ only patients were older and had a greater frequency of prior cardiovascular disease (history of MI, angina, coronary insufficiency, intermittent claudication, or congestive heart failure) and lower creatinine clearance compared to patients without MI or biomarker+ only. Multivariable analysis revealed that the only independent predictor of MI for the overall CREST population was a history of prior cardiovascular disease (Table 2). For the combined end point of MI or biomarker+ only, the multivariable predictors were history of prior cardiovascular disease and baseline creatinine clearance (Table 2). No data were available regarding the use of periprocedure beta blocker therapy. Thienopyridines use in CEA was not recorded. In CAS patients the documented use of periprocedural thienopyridines was similar in MI patients (83%), biomarker+ only patients (71%) and patients who had neither MI nor biomarker+ only (77%). Medications to lower cholesterol were recorded only in patients with a history of dyslipidemia, and there were no significant differences at baseline in use of cholesterol-lowering drugs between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Variables for Myocardial Infarction, Biomarker Positivity Only, and Neither Myocardial Infarction nor Biomarker Positivity Only

| Adjudicated MI (n = 42) | Adjudicated Biomarker+ Only (n = 20) | No MI or Biomarker+ Only (n = 2440) | P for Difference Between MI, Biomarker+ Only, and No MI or Biomarker+ Only | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 72.3 ± 8.0 | 72.3 ± 8.8 | 69.0 ± 8.9 | 0.01 |

| Male sex, % | 66.7 | 65.0 | 65.1 | 0.98 |

| White race, % | 85.7 | 90.0 | 93.4 | 0.13 |

| Symptomatic carotid stenosis, % | 52.4 | 60.0 | 52.8 | 0.81 |

| Randomized to CEA, n | 28 | 12 | 1200 | |

| Randomized to CAS, n | 14 | 8 | 1240 | |

| Hypertension, % | 95.2 | 85.0 | 85.8 | 0.21 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 40.5 | 35.0 | 30.3 | 0.33 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 92.9 | 80.0 | 84.3 | 0.27 |

| On cholesterol-lowering medication, %* | 88.6 | 93.8 | 91.8 | 0.76 |

| Current smoker, % | 22.0 | 10.0 | 26.5 | 0.20 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease, % | 65.8 | 50.0 | 43.3 | 0.02 |

| Previous CEA, % | 9.5 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 0.22 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass, % | 31.0 | 35.0 | 20.4 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 143.9 ± 23.6 | 143.0 ± 22.3 | 141.4 ± 20.3 | 0.68 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 74.3 ± 9.9 | 71.9 ± 14.8 | 74.0 ± 11.5 | 0.70 |

| Stenosis ≥ 70%, % | 83.3 | 95.0 | 86.0 | 0.45 |

| Median time from randomization to treatment, d | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 0.42 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min† | ||||

| <30 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 0.02 |

| 30–59 | 35.9 | 35.0 | 26.8 | |

| ≥ 60 | 59.0 | 55.0 | 71.3 | |

| Transfusion required, % | 7.1 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 0.003 |

| Procedural hypertension, % | 7.1 | 0 | 3.1 | 0.002 |

| Procedural hypotension, % | 11.9 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 0.23 |

MI indicates myocardial infarction; biomarker+, biomarker positivity; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; and CAS, carotid artery stenting.

Use of cholesterol medication was recorded only in those who answered affirmatively to dyslipidemia.

Creatinine clearance was calculated with the Cockcroff-Gault formula: GFR= (140−age)(weight in kg)(0.85 if female)/(72)(creatinine in mg/dL), where GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2.

Results of Multivariable Analysis of Risk Factors for Periprocedural Myocardial Infarction

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI model* | |||

| Age* | 1.03 | 0.99–1.08 | 0.19 |

| Prior cardiovascular disease or CABG* | 2.22 | 1.13–4.35 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 1.60 | 0.84–3.07 | 0.16 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min* | |||

| <30 | 2.16 | 0.47–10.02 | 0.33 |

| 30 – 59 | 1.21 | 0.57–2.61 | 0.62 |

| ≥60 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| MI or Biomarker+ only model† | |||

| Age† | 1.03 | 0.96–1.07 | 0.10 |

| Prior cardiovascular disease or CABG† | 1.73 | 1.02–2.95 | 0.04 |

| Diabetes mellitus† | 1.44 | 0.85–2.46 | 0.18 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min† | |||

| <30 | 2.97 | 0.97–9.05 | 0.06 |

| 30 – 59 | 1.23 | 0.66–2.29 | 0.52 |

| ≥60 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; and CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Thirty-eight events of 42 in the model owing to missing data.

Fifty-eight events of 62 in the model owing to missing data.

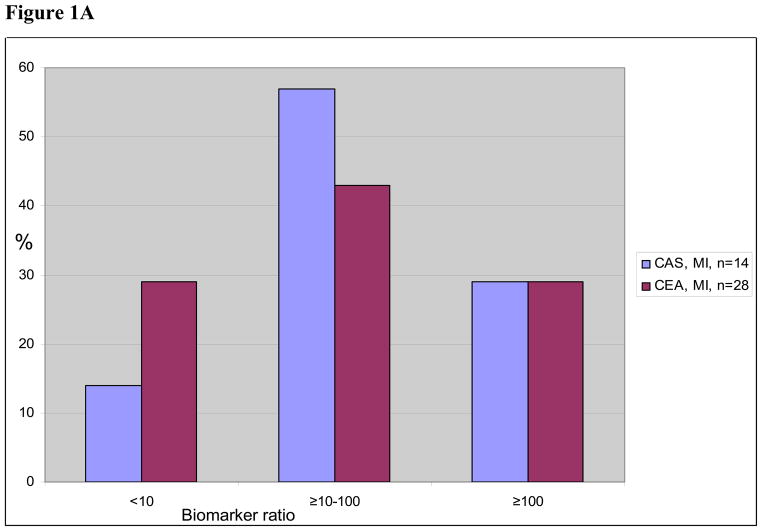

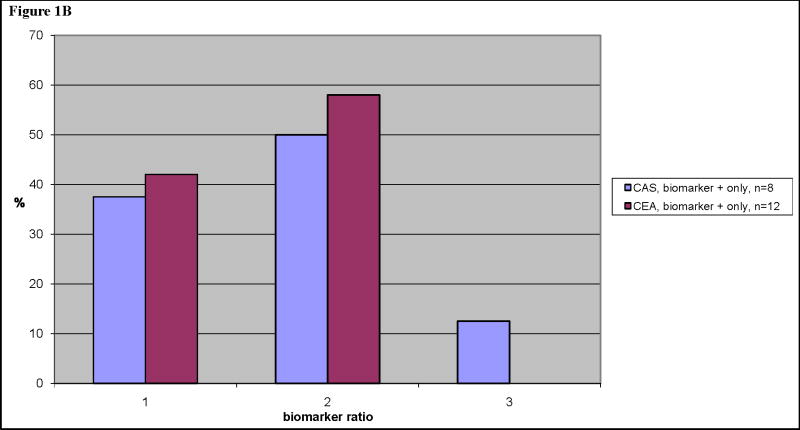

In the patients with adjudicated MIs, the median biomarker ratio was 40. In the patients with biomarker+ only, the median biomarker ratio was 14 (Table 3). Biomarker elevations were higher in the 27 MI patients with chest pain compared with the 15 MI patients without chest pain. Twenty-six of the 42 adjudicated MI patients had CK-MB in addition to troponin, and 12 (46%) had a CK-MB peak <2 times the upper limit of normal. Similarly, among 12 of 20 biomarker+ only patients with both CK-MB and troponin data, 8 (67%) had CK-MB <2 times the upper limit of normal. There were no differences in peak biomarker ratio for patients randomized to CAS compared to CEA. The distribution of biomarker ratios is shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Infarct Size by Biomarkers

| Biomarker Ratio | Peak CK, IU/L | Peak CK-MB, ng/mL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI (n=42) | 40 (12–116) | 238 (132–460) | 11.8 (5.9–25.0) |

| MI with chest pain (n=27) | 69 (26–142)* | 188 (126–382) | 11.8 (5.7–40.4) |

| MI, no chest pain (n=15) | 28 (10–63)† | 375 (217–698) | 11.6 (7.0–17.3) |

| Biomarker+ only (n=20) | 14 (9–27)‡ | 298 (119–353) | 8.3 (4.9–17.4) |

| MI or biomarker+ only, CEA (n=40) | 23 (10–73) | 253 (142–460) | 9.7 (5.2–23.6) |

| MI or biomarker+ only, CAS (n=22) | 36 (15–95) | 244 (109–448) | 10.5 (6.3–20.2) |

Values are median (interquartile range). CK indicates creatine kinase; MI, myocardial infarction; biomarker+, biomarker positivity; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; and CAS, carotid artery stenting.

P<0.05 vs biomarker+ only.

P=0.04 vs MI with chest pain.

P<0.078 vs MI.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Size distribution of biomarker ratios, myocardial infarction (MI) patient group, and percentage of total within either carotid artery stenting (CAS) or carotid endarterectomy (CEA).

Figure 1B. Size distribution of biomarker ratios, biomarker+ only patient group, and percentage of total within either CAS or CEA.

Mortality During Long Term Follow-up

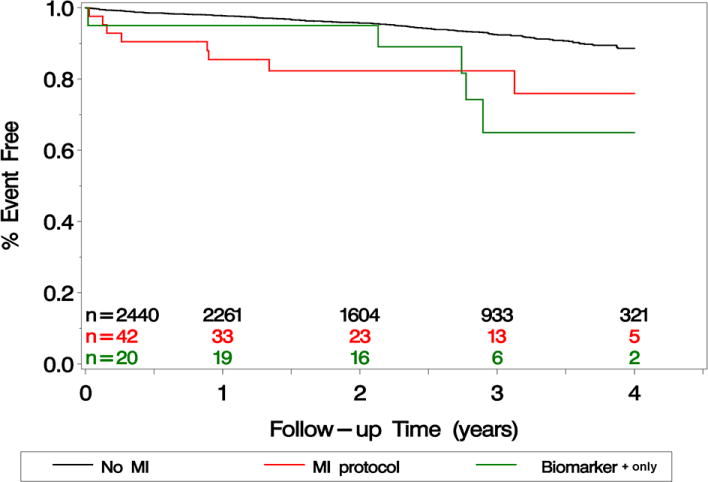

Deaths by MI, biomarker+ only, and neither are listed by the periprocedural period, year 1, and out to 4 years in Table 4. During long-term follow-up (median, 2.5 years; range, 1 to 4 years), there were 177 deaths, with an estimated 4-year mortality of 7.1%. In crude analyses, both adjudicated MI and biomarker+ only events were associated with increased mortality compared with patients without either event. The unadjusted hazard ratios were 3.40 (95% CI, 1.67 to 6.92, P<0.001 for MI) and 3.57 (95% CI, 1.46 to 8.68, P=0.005 for biomarker+ only) (Table 4 and Figure 2). In analyses that adjusted for baseline factors, including creatinine clearance, the hazard ratios for mortality remained largely unchanged for both adjudicated MI (3.67; 95% CI, 1.71 to 7.90; P=0.001) and biomarker+ only (2.87; 95% CI, 1.16 to 7.14; P=0.023; Table 4). Additional adjustment for symptomatic status and sex had little impact on the estimated risk differences. Among MI patients, there were 5 deaths in the CEA group and 3 deaths in the CAS group. For the isolated biomarker+ only patients, there were 2 deaths after CEA and 3 deaths after CAS. None of these differences were significant.

Table 4.

Mortality by Time Period After Randomization in the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stenting Trial

| Periprocedural Death, n (Cumulative %) | Death, 1 mo-1 y, n (Cumulative %) | Death, >1 y, n (Cumulative %) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI (n=42) | 1 (2.4) | 5 (14.3) | 2 (19.1) | 3.40 (1.67-6.92) | 3.67 (1.71-7.90) |

| Unadjusted P | <0.001 | ||||

| Risk factor – adjusted P | 0.001 | ||||

| Biomarker+ only (n=20) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (5.0) | 4 (25) | 3.57 (1.46-8.68) | 2.87 (1.16-7.14) |

| Unadjusted P | 0.005 | ||||

| Risk factor – adjusted P | 0.023 | ||||

| No MI or biomarker+ only (n=2440) | 9 (0.4) | 44 (2.2) | 111 (6.7) | Reference | Reference |

Multivariate model was adjusted for age, prior cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, previous coronary bypass surgery, and baseline creatinine clearance. HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction; and biomarker+, biomarker positivity.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves after randomized carotid revascularization in the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stenting Trial (CREST). Groups represented include myocardial infarction (MI) patients, biomarker+ only patients, and patients with neither MI nor biomarker+ only.

There were limited data during follow-up regarding adjunctive medical therapy with the exception of lipid lowering therapy. Among 1866 patients with a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, 95% were on lipid lowering therapy with no differences between those who died and those who lived.

Discussion

In this large randomized trial of carotid revascularization comparing CAS to CEA, either protocol-defined MI or positive biomarkers without other criteria for MI occurred in 2.5% of patients. The trial was unique because it included both patients with symptomatic and those with asymptomatic carotid disease at various levels of surgical risk, and systematically collected biomarker and other clinical data for adjudication of periprocedural MI. Both protocol-defined MI and biomarker+ only were almost twice as frequent among patients randomized to CEA. Although the degree of biomarker increase was relatively small compared with spontaneous MI events (22–29), the presence of either MI or biomarker + only was associated with significantly higher risk for subsequent mortality even after adjustment for baseline risk factors. Prior large randomized trials comparing CAS and CEA in conventional risk patients have not reported rates of MI comparable to those reported in our study. MI was not a component of the primary end point for the Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial or in the Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy (SPACE) trial. In EVA-3S, SPACE, and in the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS), cardiac biomarkers were not specified per protocol.(30–32) Accordingly, the reported rates for MI were much lower than in CREST. Specifically, the rate of MI was 0.4% for CAS and 0.8% for CEA in EVA-3S; 0.4% for CAS and 0.6% for CEA in ICSS; and 0% for both CAS and CEA in SPACE. In ICSS, fatal MI events occurred in 3 of 853 patients (0.4%) with CAS, and 5 non-fatal MIs occurred in 821 patients with CEA (0.6%).(32) Only in the high-surgical-risk, randomized Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) trial which incorporated systematic collection of CK and CK-MB, was a higher rate of MI detected, 5.9% for CEA and 2.4% for CAS. (33)

As suggested by the higher frequency of MI in SAPPHIRE, certain baseline patient factors contributed significantly to risk for periprocedural MI or elevated biomarkers in CREST. In particular, patients with known cardiovascular disease or renal insufficiency were more prone to periprocedural MI. It is premature to speculate whether these data should be used to guide patient selection for CAS versus CEA in clinical practice. Indeed, in CREST subgroup analyses, elderly patients who are likely to have an increased prevalence of both prior cardiovascular disease and renal insufficiency had improved overall outcomes with CEA compared with CAS. (1) Nevertheless, it seems advisable to implement or test protective strategies for the prevention of MI in these higher-risk patients, especially if selected to undergo CEA. Candidate approaches might include high-dose statins which have shown benefit in reducing periprocedural MI after percutaneous coronary intervention, ( 34) or more robust dual anti-platelet therapy as is used for CAS. Certainly, for asymptomatic patients identified to be at higher risk for MI or stroke after CEA or CAS, optimal medical therapy may actually be the preferred option and should be evaluated in a prospective controlled trial.

Our results do not provide direct measurements of the extent of myocardial injury, but do indicate that most of the MIs were small or moderate. One-fourth of the patients had biomarker ratios <10 times the laboratory upper limit of normal, while approximately one-half were detected only by troponin and did not meet diagnostic criteria by CK-MB. Nonetheless, the CREST patients with periprocedural MI or biomarker + only were > 3-times more likely to die during follow-up than those without MI, even after adjustment for important baseline characteristics. This is consistent with case series of patients with low level periprocedural troponin elevation following major non-cardiac surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, and other procedures (3–15, 35,36). As in these other examples, the association of even small MI with late mortality does not imply a cause-and-effect relationship. It is likely that the occurrence of periprocedural biomarker elevation or even clinical MI is a marker of more extensive atherosclerotic disease. Whether the development of an ischemic event in relation to the performance of a procedure adds further to this risk cannot be assessed in CREST, and has not been discernable from any of other multiple studies reporting such an association. Recognition of the association remains important to possibly avoid the procedure in highest-risk patients and to consider more aggressive long-term risk factor management in those patients who sustain an event.

The CREST investigation was not designed to characterize MI, so inference from this report has several limitations. Although death rates were significantly different, this result was based on only 13 deaths in the MI and biomarker+ only groups. A central core laboratory for cardiac biomarker analysis was not used. We therefore analyzed the cardiac biomarker ratio using a range of markers and site-specific assays instead of a designated quantitative level for a single marker. The use of CK and CK-MB without troponin may have identified more CEA cases to be sent to adjudication since CK and CK-MB liberation from surgical disruption of skeletal muscle is commonplace. Postprocedural biomarker assessment was limited to 6 to 8 hours after the procedure in most patients, whereas the peak detection rate of post surgical cardiac biomarkers for major surgical procedures is 24 to 48 hours after the procedure. A difference in length of stay between CAS and CEA may have increased the detection rate of biomarker abnormality in CEA, since symptoms, biomarker abnormalities and ECG changes all triggered additional biomarker measurements.

Conclusions

In the randomized CREST trial, both protocol-defined MI, and biomarker positivity without symptoms or ECG changes occurred more often with CEA than CAS. Both events were associated with increased long-term mortality, in unadjusted and risk-adjusted analyses. These findings demonstrate that the occurrence of periprocedural MI or biomarker+ only identifies a population of patients at greater risk of death in longer-term follow-up, and suggest that individualized patient risk for such events may be an important consideration in the choice of CAS or CEA, and the choice of carotid revascularization or medical therapy.

Acknowledgments

None

Funding Sources

Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 NS 038384) and supplemental funding from Abbott Vascular Solutions (formerly Guidant).

Footnotes

Disclosures

J.L. Blackshear: None. D.E. Cutlip: None. G.S. Roubin: Abbott Vascular, Inc., Royalties, Cook Inc., Royalties. M.D. Hill: None. P.P. Leimgruber: None. R.J. Begg: None. D.J. Cohen: Research Grant, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific. Consultant/Advisory Board, Cordis, Inc., Medtronic, Inc. J.F. Eidt: None. C.R. Narins: None. RJ Prineas: None. S.P. Glasser: None. J.H. Voeks: None. T.G. Brott, for the CREST Investigators: Honoraria, Sahs Memorial Lecture University of Iowa, VEITH Symposium, American Academy of Neurology 62nd Annual Meeting, Heritage Valley Health System, American Society of Neuroradiology 48th Annual Meeting, Massachusetts General Hospital, Pennsylvania Advances in Stroke.

Contributor Information

Joseph L. Blackshear, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL.

Donald E. Cutlip, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Boston, MA.

Gary S. Roubin, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York City, NY.

Michael D. Hill, University of Calgary, Calgary Stroke Program, Foothills Hospital, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Pierre P. Leimgruber, Providence Spokane Heart Institute, Spokane, WA.

Richard J. Begg, Heritage Valley Health System, Heart & Vascular Center, Beaver, PA.

David J. Cohen, Saint Luke’s MidAmerica Heart & Vascular Institute, Kansas City, MO.

John F. Eidt, University of Arkansas for Medical Science, Little Rock, AR.

Craig R. Narins, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY.

Ronald J. Prineas, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

Stephen P. Glasser, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Jenifer H. Voeks, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Thomas G. Brott, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL.

References

- 1.Brott TG, Hobson RW, II, Howard G, Roubin GS, Clark WM, Brooks W, Mackey A, Hill MD, Leimgruber PP, Sheffet AJ, Howard VJ, Moore WS, Voeks JH, Hopkins LN, Cutlip DE, Cohen DJ, Popma JJ, Ferguson RD, Cohen SN, Blackshear JL, Silver FL, Mohr JP, Lal BK, Meschia JF. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis SM, Donnan GA. Carotid-artery stenting in stroke prevention. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:800–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1005220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim LJ, Martinez EA, Faraday N, Dorman T, Fleisher LA, Perler BA, Williams GM, Chan D, Pronovost PJ. Cardiac troponin I predicts short-term mortality in vascular surgery patients. Circ. 2002;106:2366–2371. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036016.52396.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landesberg G, Shatz V, Akopnik I, Wolf YG, Mayer M, Berlatzky Y, Weissman C, Mosseri M. Association of cardiac troponin, CK-MB, and postoperative survival after major vascular surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oscarsson A, Eintrei C, Anskar S, Engdahl O, Fagerstrom L, Blomquist P, Fredriksson M, Swahn E. Troponin T-values provide long-term prognosis in elderly patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2004:1071–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bursi F, Babuin L, Barbieri A, Politi L, Zennaro M, Grimaldi T, Rumolo A, Gargiulo M, Stella A, Modena MG, Jaffe AS. Vascular surgery patients: perioperative and long-term risk according to the Acc/AHA guidelines, the additive roles of post-operative troponin elevation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2448–2456. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFalls EO, Ward HB, Mortiz TE, Apple FS, Goldman S, Pierpont G, Larsen GC, Hattler B, Shunk K, Littooy F, Santilli S, Rapp J, Thottapurathu L, Krupski W, Reda DJ, Handerson WG. Predictors and outcomes of a perioperative myocardial infarction following elective vascular surgery in patients with a documented coronary artery disease: results of the CARP trial. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:394–401. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeHert SG, Longrois D, Yang H, Fleisher LA. Does the use of a volatile anesthetic regimen attenuate the incidence of cardiac events after vascular surgery? Acta Anaesth Belg. 2008;59:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong CP, Lam QT, Ryan JE, Sinnappu RN, Lim WK. Incidence of post-operative troponin I rises and 1-year mortality after emergency orthopaedic surgery in older patients. Age and Ageing. 2009;38:168–174. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavallini C, Rugolotto M, Savonitto S. Prognostic significance of creatine kinase release after percutaneous coronary intervention. Ital Heart J. 2005;6:522–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad A, Singh M, Lerman A, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR, Jr, Rihal CS. Isolated elevation in troponin T after percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with higher long-term mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1765–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Jimenez F, Goldman L, Sacks DB, Thomas EJ, Johnson PA, Cook EF, Lee TH. Prognostic value of cardiac troponin T after noncardiac surgery: 6-month follow-up data. J Am CollCardiol. 1997;29:1241–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)82754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Manch Y, Perel A, Coriat P, Godet G, Bertrand M, Riou B. Early and delayed myocardial infarction after abdominal aortic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:885–91. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kertai MD, Boersma E, Klein J, van Urk H, Baxt JJ, Poldermans D. Long-term prognostic value of asymptomatic cardiac troponin T elevations in patients after major vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nienhuis MB, Ottervanger JP, Bilo HJG, Dikkeshchei BD, Zijlstra F. Prognostic value of troponin after elective percutaneous coronary intervention: A meta-snalysis. Cath Cardiovasc Intervent. 2008;71:318–324. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins LN, Roubin GS, Chakhtoura EY, Gray WA, Ferguson RD, Katzen BT, Rosenfield K, Goldstein J, Cutlip DE, Morrish W, Lal BK, Sheffet AJ, Tom M, Hughes S, Voeks J, Kathir K, Meschia JF, Hobson RW, II, Brott TG. The carotid revascularization endarterectomy vs stenting trial: credentialing of interventionalists and final results of lead-in phase. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2010;19(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheffet AJ, Roubin G, Howard G, Howard V, Moore W, Meschia J, Hobson RW, II, Brott TG. Design of the carotid revascularization endarterectomy vs. stenting trial (CREST) International Journal of Stroke. 2010;5:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobson RW., II CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarteectomy versus Stent Trial): background, design, and current status. Semin Vasc Surg. 2000;13:139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The GRACE Investigators. Rationale and design of the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) Project: A multinational registry of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2001;141:190–9. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.112404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman SG, Steg PG, Eagle KA, Foss KAA, Lopez-Sendon J, Montalescot G, Budaj A, Kennelly BM, Gore JM, Allegrone J, Granger CB, Gurfunkel EP. The diagnostic and prognostic impact of the redefinition of acute myocardial infarction: Lessons from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malasky BR, Alpert JS. Diagnosis of myocardial injury by biochemical markers: Problems and promises. Cardiology in Review. 2002;10(5):306–317. doi: 10.1097/00045415-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannitsis E, Steen H, Kurz K, Ivandic B, Simon AC, Futterer S, Schild C, Isfort P, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study for quantification of infarct size comparing directly serial versus single time-point measurements of cardiac troponin T. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzivoni D, Koukoui D, Guetta V, Novack L, Cowing G for the CASTEMI Study Investigators. Comparison of troponin T to creatine kinase and to radionuclide cardiac imaging infarct size in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:753–757. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallen J, Buser P, Schwitter J, Petzelbauer P, Geudelin B, Fagerland MW, Jaffe AS, Atar D. Relation of cardiac troponin I measurements at 24 and 48 hours to magnetic resonance-determined infarct size in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Licka M, Zimmerman R, Zehelein J, Dengler TJ, Katus HA, Kubler W. Troponin T concentrations 72 hours after myocardial infarction as a serological estimate of infarct size. Heart. 2002;87:520–524. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.6.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohmer E, Hoffmann P, Abdelnoor M, Seljeflot I, Halvorsen S. Troponin T concentration 3 days after acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction predicts infarct size and cardiac function at 3 months. Cardiology. 2009;113:207–212. doi: 10.1159/000201991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steen H, Giannitsis E, Futterer S, Merten C, Juenger C, Katus HA. Cardiac troponin T at 96 hours after acute myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and cardiac function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2192–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Younger JF, Plein S, Barth J, Ridgway JP, Ball SG, Greenwood JP. Troponin-I concentration 72 h after myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and presence of microvascular obstruction. Heart. 2007;93:1547–1551. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.109249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassan AKM, Bergheanu SC, Hasan-Ali H, Liem SS, van der Laarse A, Wolterbeek R, Atsma DE, Schalij MJ, Jukema JW. Usefulness of peak Troponin-T to predict infarct size and long-term outcome in patients with first acute myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier P, Knapp G, Tamhane U, Chaturvedi S, Gurm HS. Short term and intermediate term comparison of endarterectomy versus stenting for carotid artery stenosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knur R. Carotid artery stenting: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Vasa. 2009;38:281–91. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.38.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ederle J, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, Bonati LH, van der Worp HB, de Borst GJ, Lo TH, Gaines P, Dorman PJ, Macdonald S, Lyrer PA, Hendriks JM, McCollum C, Nederkoorn PJ, Brown MM for the International Carotid Stenting Study Investigators. Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:985–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, Fayad P, Katzen BT, Mishkel GJ, Bajwa TK, Whitlow P, Strickman NE, Jaff MR, Popma JJ, Snead DB, Cutlip DE, Firth BG, Ouriel K. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1493–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasceri V, Patti G, Nusca A, Pristipino C, Richichi G, Di Sciascio D on behalf of the ARMYDA Investigators. Randomized Trial of atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial damage during coronary intervention: Results from the ARMYDA (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage during Angioplasty) Study. Circulation. 2004;110:674–78. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137828.06205.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motamed C, Motamed-Kazerounian G, Merle JC, Dumerat M, Yakhou L, Vodinh J, Kouyoumoudjian C, Duvaldestin P, Bedquemin JP. Cardiac troponin I assessment and late cardiac complications after carotid stenting or endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:769–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domanski MJ, Mahaffey K, Hasselblad V, Brener SJ, Smith PK, Hillis G, Enogoren M, Alexander JH, Leby JH, Chaitman BR, Broderick S, Mack MJ, Pieper KS, Farkouh ME. Association of myocardial enzyme elevation and survival following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2011;305:585–591. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]