Abstract

A growing body of literature supports a link between positive emotions and health in older adults. In this article, we review evidence of the effects of positive emotions on downstream biological processes and meaningful clinical endpoints, such as adult morbidity and mortality. We then present relevant predictions from lifespan theories that suggest changes in cognition and motivation may play an important role in explaining how positive emotions are well maintained in old age, despite pervasive declines in cognitive processes. We conclude by discussing how the application of psychological theory can inform greater understanding of the adaptive significance of positive emotions in adulthood and later life.

Keywords: Aging, Health, Positive Emotions, Resilience

The arc of emotion in the second half of life is marked by divergent trajectories. While negative emotions, particularly anger, decline with advancing age, positive emotions remain fairly stable (Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Charles, Reynolds, & Gatz, 2001). Much of the existing literature has focused on identifying the mechanisms underlying age differences in the regulation and experience of emotion (see Charles & Carstensen, 2009; Scheibe & Carstensen, 2010; Urry & Gross, 2010, for a review). In this article, we highlight studies that chart the health significance of emotional aging. We focus on positive emotions—defined as pleasant feeling states such as joy, contentment, and love that motivate adaptive approach behavior (Fredrickson, 2004).We review evidence of explanatory pathways linking positive emotions and health, giving emphasis to the major approaches, empirical findings, and methodological gaps that currently exist in the literature. We distinguish studies assessing more enduring, stable positive emotions or traits from those measuring or inducing short-term changes in positive emotions or states. We then summarize relevant predictions from lifespan theories that provide motivational and cognitive accounts of age differences in emotional well-being. We conclude by discussing how integrating existing empirical findings with current theories of emotional aging can offer a more complete understanding of the health significance of positive emotions in adulthood and later life.

THEORETICAL MECHANISMS LINKING POSITIVE EMOTION TO HEALTH

Accumulating evidence supports an association between positive emotion and enhanced physical health (see Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Pressman & Cohen, 2005, for a review). Across experimental and prospective epidemiological studies, significant aspects of adult health influenced by positive emotion include self-reported health, physical functioning, disease severity, and mortality. Although the literature is not without theoretical gaps and methodological inconsistencies (see Pressman & Cohen, 2005, for a discussion), overall, the data suggests that positive emotions have measureable health benefits, the summative effect of which may be to delay the onset of frank disease and extend healthy functioning in later life.

How might positive emotions influence health in adulthood and later life? Ong (2010) outlined four potential pathways through which positive emotions contribute to adult health outcomes: health behaviors, physiological systems, stressor exposure, and stress undoing (these mirror some of the pathways by which stress and personality affect health; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2004; Mroczek & Spiro, 2007). Overall, evidence supporting these pathways are apparent both at the level of stable traits and at the level of naturally occurring or induced positive emotional states.

Health Behaviors

Considerable associational evidence implicates negative health practices and behaviors in the development of acute and chronic health conditions (Adler & Matthews, 1994). Moreover, because the effects of negative health behaviors (e.g., poor nutrition, a sedentary lifestyle) accumulate with age, older adults are at greater risk for chronic and acute health disorders. Importantly, individual differences in positive emotion may afford protection from health risks by affecting the initiation and maintenance of positive health practices over time. Integrative reviews indicate that trait positive emotion is prospectively associated with greater health-enhancing behaviors that support restorative processes (Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Steptoe, Dockray, & Wardle, 2009). One powerful source of restoration is sleep, which provides numerous recuperative benefits. Aging is associated with impairments in sleep quality, including poorer sleep efficiency and greater sleep disturbances (Bloom, Ahmed, Alessi et al., 2009). While progressive loss of sleep quality can have adverse effects on the body, empirical evidence demonstrates that positive emotions may be conducive to adaptive sleep patterns, especially among older adults (Steptoe, O'Donnell, Marmot, & Wardle, 2008). These findings notwithstanding, a recent meta-analytic review of fifty-four prospective studies concluded that in healthy older adults (60 years and older), the beneficial effects of psychological well-being on mortality persist even after controlling for health behaviors (Chida & Steptoe, 2008), suggesting that there may be more than one pathway through which positive emotion may exert influence on adult health outcomes.

Physiological Systems

Alongside the proliferation of research on behavioral mechanisms has been an increase in studies probing the physiological substrates of positive emotion, particularly in older adults (Ong, 2010; Steptoe, O’Donnell, Badrick, Kumari, & Marmot, 2008). Aging, of course, is associated with progressive decrements in multiple physiological systems (cardiovascular, immunologic, neuroendocrine). These physiological pathways, in turn, are implicated in diverse health outcomes associated with aging, such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and coronary heart disease (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002). While prolonged activation of neuroendocrine, immune, and cardiovascular systems can have adverse effects on the body, increasing evidence suggests that positive emotion may alter disease risk via dampening of these physiological systems. In an illustrative study, Steptoe, Wardle, and Marmot (2005) showed that after accounting for health status and psychosocial factors, trait positive emotion was associated with lower salivary cortisol output both on working and nonworking days, lower ambulatory heart rate, and reduced fibrinogen responses (a marker of immune competence). More recent research has highlighted the importance of positive emotion following major life events. For example, data from the Midlife in the United Sates (MIDUS) survey and the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE), Ong, Fuller-Rowell, Bonanno, and Almeida (2011) found that deficits in trait positive emotion following spousal loss fully accounted for the differences in observed diurnal cortisol slopes. Moreover, the associations were independent of trait negative emotion, suggesting that trait positive emotion may have a salutary health effect that is separate from that of psychological distress.

Growing experimental evidence suggests that positive emotion may also influence health by altering aspects of immune function known to affect disease susceptibility. Marsland, Pressman, and Cohen (2007) reviewed 8 studies that assessed the effects of induced positive emotion on levels of salivary immunoglobulin A (SIgA), a component of the immune system that is found in saliva and is involved the body’s defense against infection. All eight studies reviewed found clear evidence that state positive emotion was related to increases in sIgA levels. Although these studies focused on healthy young adults, these data provide promising evidence that alterations in physiological systems (e.g., via immune function) may represent an important intermediate pathway linking positive emotion with health in later adulthood. Indeed, such effects may be of particular importance for older adults, among whom the accrual of immunological deficits may accentuate susceptibility to disease and early mortality.

Stressor Exposure

Linking positive emotion to health necessitates deeper understanding of the environmental mechanisms underlying patterns of age variation in disease states. Individual differences in stressor exposure have long been suspected as contributing to age-related differences in vulnerability to illness and disease. Cohen and Williamson (1991) proposed that stress may interact with age to precipitate the aging of the immune system. Subsequent reviews (e.g., Kiecolt-Glaser & Glaser, 2001) have supported the hypothesis that differential exposure to stressors hastens age-related declines in physical health. By contrast, increasing evidence suggests that positive emotion could directly impact health outcomes by lowering overall stressor exposure. Prospective studies of community-dwelling older adults, for example, indicate that positive emotion is associated with reduced exposure to acute health conditions including incident stroke, myocardial infarction, and rehospitalization for coronary problems (Pressman & Cohen, 2005).

There is also evidence that positive emotion may play a role in mitigating exposure to stressors associated with aging, including pain, inflammation, and disability. For example, using repeated-measures data from a sample of women with osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia, Zautra, Johnson, and Davis (2005) found that higher levels of overall positive emotion predicted a decrease in pain reports during subsequent weeks. Steptoe and colleagues (2008) assessed associations between trait positive emotion and inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and interleukin-6) in healthy men and women. The results indicated that trait positive emotion was associated with reduced levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 concentration over the day in women (but not in men). Ostir and associates (2004) examined the relationship between trait positive emotion and subsequent risk of frailty in a sample of non-institutionalized Mexican Americans. After adjusting for baseline medical conditions and demographic predictors, trait positive emotion was associated with a 3% decreased risk of frailty. Overall, these studies provide preliminary evidence of the prospective association between positive emotion and diminished stressor exposure.

Stress Reactivity and Recovery

Whereas positive emotion is believed to directly affect health via behavioral, physiological, and stressor exposure pathways, accruing experimental research—and older adults’ subjective reports of their own experience—suggest that positive emotion may also benefit health by ameliorating or buffering the adverse effects of stress. Age differences in stress reactivity and recovery are supported by experimental studies showing that older adults exhibit greater stress-induced immune and cardiovascular dysregulation compared to younger adults (Uchino, Birmingham, & Berg, 2010). Support for the stress-buffering effect of positive emotion can be drawn from experimental-challenge and naturalistic-diary studies (see Pressman & Cohen, 2005, for a review) demonstrating that positive emotion can alter the severity and duration of stress responses that foster disease vulnerability. For instance, Cohen and colleagues (2006) showed that following experimental exposure to a respiratory virus, adults who scored higher on a measure of trait positive emotion showed diminished risk of developing upper respiratory illness. Brummett, Boyle, Kuhn, Diegler, and Williams (2009) found that trait positive emotion was related to lower blood pressure reactivity during sadness recall (but not during anger recall), more epinephrine, and lower cortisol rise after waking. Other studies have utilized repeated measures of positive emotional states and examined their contemporaneous role in dampening statelike fluctuations in stress responses (e.g., Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2004; Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006). Zautra, Smith, Affleck, and Tennen (2001), for example, found that weekly positive emotions attenuated the relationship between pain and negative emotion in a sample of women with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Taken together, these findings suggest that both trait and state positive emotion are associated with lower physiological reactivity to stress.

In addition to attenuating stress reactivity, positive emotions may also contribute to faster recovery from stress-related physiological arousal. Strong empirical support for this pathway has been reported in a number of studies with younger adults, which demonstrate that induced positive emotion (via film) following laboratory stress results in a more rapid return to baseline levels of heart rate and blood pressure (e.g., Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, & Tugade, 2000). There is also evidence that positive emotions facilitate adaptive stress recovery in older adults. For example, in naturalistic diary studies, daily positive emotions have been found to mitigate the effects of negative emotion on blood pressure, even after adjusting for individual differences in trait affect and other potential confounds (Ong & Allaire, 2005). Overall, these findings further support the idea that positive emotions facilitate adaptive recovery from the effects of negative emotions.

In sum, the studies described above suggest that health-enhancing behaviors, reduced activation of physiological processes, diminished stressor exposure, and adaptive stress reactivity and recovery may be among the important pathways linking positive emotion to adult health outcomes. Increasing evidence also suggests the health effects of each of these pathways may be most apparent in later life, although more research on age differences in the associations between positive emotion and health-related processes is clearly needed. One provocative hypothesis is that the processes that foster greater emotional resilience begin during the middle years (Labouvie-Vief, 2003; Mroczek, 2004). If so, midlife may prove to be an influential period on the pathway to adaptive emotional aging.

EXPLAINING AGE DIFFERENCES IN EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING

A large body of empirical research documents age differences in emotional well-being (see Charles, 2010; Charles & Carstensen, 2009, for a review). Cross-sectional (Carstensen, et al., 2000; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998; Stone, Schwartz, Broderick, & Deaton, 2010) and longitudinal studies (Charles, et al., 2001; Costa, Zonderman, McCrae et al., 1987; Griffin, Mroczek, & Spiro, 2006) reveal that negative emotions occur with less frequency, whereas positive emotions occur with similar if not greater frequency across age cohorts, though there is some evidence that these age associations may be moderated by functional health limitations (Kunzmann, Little, & Smith, 2000) and the onset of terminal decline processes (Gerstorf, Ram, Mayraz et al., 2010). Although age may shape emotional experience, younger and older adults differ in a multitude of ways. In this section, we review predictions from two prominent lifespan theories—socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999) and dynamic integration theory (Labouvie-Vief, 2003)—that suggest changes in cognition and motivation may play an important role in explaining how positive emotions are well maintained in old age, despite pervasive declines in resource-intensive processes. Overall, we find that the literature contains plausible accounts of mechanisms associated with age differences in emotional well-being, but contains few published studies that provide formal tests of mechanistic hypotheses.

Motivation and the Positivity Effect

Socioemotional selectivity theory provides a motivational account for the apparent improvements in emotional well-being with age (Carstensen & Charles, 1998). The theory postulates that when time is perceived as limited, goals emphasizing emotion and meaning are prioritized over those aimed at gaining knowledge and information. This age-associated shift in motivation, in turn, is predicted to have consequences for information processing, such that older adults are more likely to prioritize positive over negative material—a phenomenon termed the “positivity effect” (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005). Socioemotional selectivity theory, however, predicts that the specific processing mechanisms involved in the positivity effect (e.g., attention and memory) may also contribute to age differences in emotional regulation. Direct evidence consistent with this later prediction is limited, however (for a discussion, see Scheibe & Carstensen, 2010).

Evidence supports a developmental pattern in which the ratio of positive to negative material remembered increases with age. This positivity effect in memory has been documented in studies of recall and recognition memory (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003), working memory (Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, & Carstensen, 2005), autobiographical memory (Kennedy, Mather, & Carstensen, 2004), and mutual reminiscing (Pasupathi & Carstensen, 2003). Importantly, and consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory, age differences in the positivity effect can be eliminated by making salient emotional goals (Mather & Johnson, 2003) or by controlling future time perspective (Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2007). Finally, there is some evidence (e.g., Kennedy, et al., 2004; Pasupathi & Carstensen, 2003) that the positivity effect in memory may operate in the service of emotional well-being by enhancing the experience of positive emotion.

The positivity effect is present not only in memory, but also in attention. Studies examining visual attention, for example, have found that older adults show a looking preference toward positive and away from negative stimuli (Isaacowitz, Wadlinger, Goren, & Wilson, 2006a, 2006b; Mather & Carstensen, 2003). Moreover, recent research suggests that this positivity effect in attention may serve a critical regulatory function (Isaacowitz, Toner, Goren, & Wilson, 2008; Isaacowitz, Toner, & Neupert, 2009), making it easier for older adults to manage disruptions in emotional experience. For example, in a recent eye-tracking study, Issacowitz, Toner, and Neupert (2009) found that older adults with good executive functioning displayed a pattern of mood-incongruent positive gaze, looking toward positive and away from negative faces when in a bad mood. These findings extend related work (e.g., Knight, Seymour, Gaunt et al., 2007; Mather & Carstensen, 2005) by demonstrating that a major function of motivated selective attention is to enhance positive emotion and promote emotion regulation.

Cognitive Control and Emotion Regulation

Whereas socioemotional selectivity theory spotlights motivation as a key factor in age-related improvements in emotion regulation, dynamic integration theory (Labouvie-Vief, 2003) holds that changes in underlying executive processes (e.g., cognitive control) account for at least some of the observed age differences in emotional well-being. In particular, the theory predicts that diminishing cognitive control capacities associated with aging lead to a gradual shift from a more complex mode of emotion regulation to one emphasizing optimization of individual well-being. That an age-related decrease in affect complexity may paradoxically result in an increase in affect optimization is suggested by a number of findings in the literature. For example, in a cross-sectional study comparing the regulatory styles of younger, middle aged, and older adults, Labouvie-Vief and Medler (2002) reported that older adults displayed a pattern of high optimization (high positive affect) along with low complexity (e.g., high denial and repression). This pattern was confirmed in a recent 6-year longitudinal study (Labouvie-Vief, Diehl, Jain, & Zhang, 2007). Consistent with dynamic integration theory, the findings suggested that older adults displayed a developmental trajectory of increasing optimization and decreasing complexity.

As noted, dynamic integration theory predicts that affect optimization reflects a compensatory response to losses in cognitive control with age rather than a motivated shift in resource allocation as suggested by socioemotional selectivity theory. One implication of this prediction is that age-related increases in well-being may be driven, in part, by emotion regulation strategies that are automatic and relatively effortless. To the extent that age-associated declines in cognitive resources result in greater difficulty inhibiting emotionally arousing stimuli, dynamic integration theory also predicts prolonged emotional arousal would lead to impairments in cognitive-affective complexity with age (Labouvie-Vief, 2003). In support of this prediction, Wurm, Labouvie-Vief, Aycock, Rebucal, and Koch (2004) found that older adults (but not younger adults) had difficulty processing high-arousing stimuli in a study using an emotional Stroop task. It is noteworthy that this finding is also consistent with a growing body of work suggesting that sustained exposure to highly arousing stimuli may result in the reduction (or even elimination) of age-associated improvements in emotional well-being (see Charles, 2010; Charles & Carstensen, 2009, for a discussion).

INTEGRATING THEORY AND RESEARCH

Although most theories recognize positive emotion as an important outcome of emotional aging, studies that move beyond piecemeal approaches to testing integrative models remain few in number. Below we briefly highlight three directions for future research that illustrate how the application of psychological theory can inform greater understanding of the significance of positive emotion in adulthood and later life.

Aging and the Health Effects of Positive Emotion

Experimental and prospective investigations of positive emotion and health have examined older adults and, by and large, have not compared younger, middle-aged, and older adults in the same study. Based on existing evidence, several effects can be predicted. First, if emotional goals such as “feeling good” assume greater primacy with age, then there should be age-differences in the relative impact of positive emotion on meaningful clinical endpoints such as decreased mortality and increased longevity. Although direct evidence of age differences is limited, this prediction is supported by integrative reviews suggesting that positive emotion is more strongly associated with survival among community-dwelling older adults over the age of 60 (Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Pressman & Cohen, 2005).

Second, inasmuch as positive emotions contribute to delaying the onset of age-related morbidity, a reasonable hypothesis is that associations between positive emotion and pre-disease pathways should be stronger in populations at risk because of age. As discussed earlier, increasing evidence suggests that aging is associated with heightened cardiovascular reactivity to psychosocial stress (Uchino, et al., 2010). Exaggerated stress responsivity, in turn, has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of a broad array of coronary conditions, including stroke, myocardial ischemia, and hypertension (Pickering & Gerin, 1990). Importantly, a recent study by Ong and Isen (2010) showed that that experimental manipulations of positive emotion (via film induction) prior to a stressful stimulus (i.e., Trier Social Stress Test) led to attenuated cardiovascular reactivity relative to a neutral condition, with stronger effects emerging for older adults compared with younger adults. Although the literature on age differences in underlying pathways connecting positive emotion with health is sparse, these findings provide additional experimental footing for the postulated buffering effect (Kok, Catalino, & Fredrickson, 2008) by setting positive emotion theory and research within a lifespan context.

Finally, age-differences in the physiological manifestations of positive emotion should vary by level of activation or arousal, with activated or high arousal positive emotions (e.g., excitement, joy) triggering greater physiological responses than unactivated or low arousal positive emotions (e.g., calm, contentment). This prediction is supported by a recent meta-analysis and empirical review (Pinquart, 2001; Pressman & Cohen, 2005) that show (a) smaller age effects associated low arousal positive emotions than with high arousal positive emotions and (b) stronger associations between high arousal positive emotions and heightened cardiovascular and immune responses, particularly in persons with chronic or terminal illness and among institutionalized older adults. While these findings are provocative, studies of activation/arousal as a potential link in the chain connecting positive emotion and adult health remain largely unintegrated (Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Observational studies that have focused on the health effects of activated and unactivated positive emotions have often failed to include adequate controls for negative emotion. Additionally, laboratory studies of induced positive emotions have not always included manipulation checks, thus complicating comparisons across studies; this is a limitation of the research to date. These important limitations notwithstanding, the suggestion that that low arousal or unactivated positive emotions may be associated with health benefits is in accord with experimental research (Isen, 2008) showing that mild positive affect can have a marked influence on cognitive processes and social behavior. In turn, these resources may promote psychological resilience and trigger increases in positive emotions over time (Ong, Bergeman, & Boker, 2009; Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Bonanno, 2010).

Aging and the Regulation of Positive Emotion

Although supportive evidence exists that emotion regulation processes are linked to well-being (Gross & John, 2003), there is growing recognition that the specific emotion regulatory acts that people engage in may vary with age. Building on earlier work, Urry and Gross (2010) recently proposed a process model of emotion regulation and aging that is consistent with the meta-theory of selection, optimization, and compensation suggested by Baltes and Baltes (1990). In particular, the selection, optimization, and compensation with emotion regulation (SOC-ER; Urry & Gross, 2010) framework posits that aging is associated with increased selectivity in the use of specific regulatory strategies (e.g., situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, response modulation) that can be further classified in terms of when they occur in the emotion-generative process (i.e., antecedent focused-regulation vs. response-focused regulation). Moreover, as with socioemotional selectivity theory, motivation is a central component of the SOC-ER framework, with the implication being that age-related changes in motivation prompt the selective use of specific types of regulation strategies in the service of well-being.

Age differences have been demonstrated in both antecedent-focused (i.e., situation selection, attentional deployment, cognitive change) and response-focused (i.e., response modulation) processes. For instance, age differences in the selection of social goals (e.g., close social partners) appear to have a positive impact on emotional well-being: Compared with younger adults, older adults report being in a more positive and less negative mood when they interact with family members and avoid arguments with others (Charles & Piazza, 2007; Charles, Piazza, Luong, & Almeida, 2009). In addition, older adults have been found to use attentional deployment and positive reappraisal (antecedent-focused strategies) more frequently, and with greater efficacy, than younger adults (Isaacowitz, et al., 2009; Shiota & Levenson, 2009). Finally, there is also some evidence that older adults are less likely than younger adults to use unhealthy response-focused regulation strategies, such as expressive suppression, as a means of inhibiting ongoing emotion response tendencies (John & Gross, 2004).

Although the study of age differences in emotion regulation processes appears promising, several unanswered questions remain. First, are there regulatory processes that have the specific function of sustaining or increasing positive emotional experience? While additional research on this question is clearly needed, theory and findings suggest that there are individual differences in positive emotion regulation (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2007). For example, evidence from a number of investigations supports the conclusion that savoring, a regulatory strategy aimed at maintaining and enhancing positive emotion (Bryant, 1989), can have salutary effects on health and well-being (Bryant, 2003; Wood, Heimpel, & Michela, 2003). Additionally, recent research (conducted primarily with younger adults) suggests that beliefs about the malleability of emotions (i.e., implicit theories) can exert a powerful influence on social and emotional functioning (Tamir, John, Srivastava, & Gross, 2007). Do implicit theories of emotion vary with age, and if so, what effect do these associations have on the experience and regulation of positive emotion? Finally, if older adults tend to be in a more positive emotional state compared to younger adults (Mroczek, 2001), then the question arises as to whether the experience of positive emotion itself can enhance older adults’ emotion regulation abilities 2011). Robust evidence consistent with this expectation comes from decades of research that demonstrate positive emotions have a facilitative effect on attention, motivation, and decision-making (see Ashby, Isen, & Turken, 1999; Isen, 2008 for a review). Moreover, the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2004) suggests that positive emotions may widen the scope of visual attention and social cognition, which over time, may enhance and increase one’s reserve capacity. Thus, momentary experiences of positive emotion should account for some of the known age-related positivity effects in attention. In turn, the accrued experience of positive emotion should build assets (e.g., psychological resilience) that afford certain individuals the ability to automatically activate positive emotions, with minimal effort. Such experiences may be of particular relevance for older adults, among whom declining cognitive resources may result in increased reliance on implicit affective processes (Carstensen, Mikels, & Mather, 2006). This possibility remains to be tested.

Aging and the Ratio of Positive to Negative Emotion

Although most theories view affect balance as a hallmark of subjective well-being, few specify how much positivity is actually needed to produce a state of optimal well-being or flourishing (Keyes, 2002). Recent empirical work, however, has begun to examine the limited research on positive emotions and flourishing. For example, Fredrickson and Losada (2005) found that optimal mental health was associated with a ratio of positive to negative emotion at or above 2.9 to 1. Similar results were obtained by Waugh and Fredrickson (2006) in a prospective study of social relationships and by Ong and Burrow (2010) in a recent experimental investigation of social broadening.

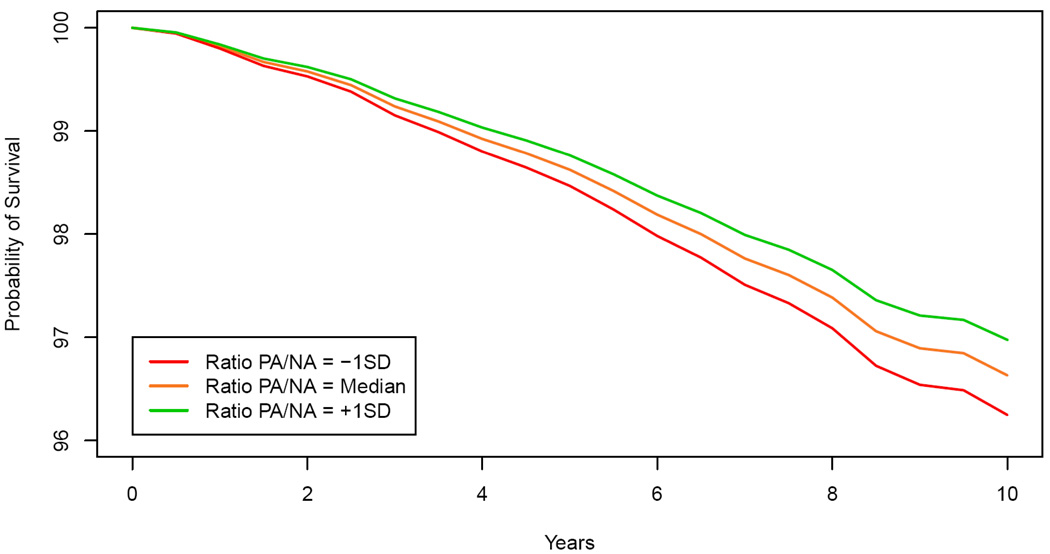

Evidence for the health benefits of positivity in older adults comes from a study by Carstensen and colleagues ( 2011), who found that positive emotional experience (assessed by subtracting the average of negative emotion from the average of positive emotion) was predictive of survival. Although these findings are consistent with the general expectation that affect balance is predictive of health, a recent prospective study provided a more direct test of Fredrickson and Losada’s (2005) theory of positivity. Specifically, Using data from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS), Ong and Mroczek (2010) examined the degree to which positivity ratios predicted survival over a 10 period. Following Waugh and Fredrickson (2006), a positive emotion was counted as being felt if it was greater than or equal to 2, and a negative emotion as being greater than or equal to 1. The number of positive emotions was then divided by the number of negative emotions to create a positivity ratio for each participant. Results support the theory (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005) and showed that participants high in positivity had a lower mortality risk compared with those low in positivity. Cox regression analyses indicated that ratio of positive to negative emotion was significantly associated with the hazard of mortality, with a hazard ratio (HR) of .95, 95% confidence interval (CI) = .90–1.00; p < .05. Individuals who experienced high positivity ratios survived longer than those who experienced low positivity ratios. Figure 1 shows the survival curves for three groups separated by median split. Interestingly, the median positivity ratio in this sample was 3.0, with those low in positivity (1SD below the median) experiencing an odds of death that was 1.34 times greater than those high in positivity.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for three groups of positivity defined by median split (adjusted for age, gender, race, education, and depression).

Finally, although there is evidence linking positivity ratios to mental flourishing and longevity, there is also reason to think that this association may be driven by a healthy aging effect. That is, although positive emotions may affect health, health status itself may also affect how individuals experience positive emotions in later life. A bidirectional account of positive emotions and health is consistent with broaden-and-build theory which suggests that positive emotions and health serially influence each other, producing an “upward spiral” toward enhanced well-being (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002). Other indirect evidence consistent with this expectation can be seen in studies of individuals with advanced diseases, in which high levels of positive emotion have been observed to be detrimental to health (Brown, Butow, Culjak, Coates, & Dunn, 2000; Devins, Mann, Mandin et al., 1990). Perhaps in these circumstances (e.g., life-threatening illness), positive emotional resources are of limited utility to enhancing health, because it is unclear how such resources should be directed. Although not well studied, this reasoning suggests an empirically testable hypothesis. Inasmuch as positivity is a resource that can influence multiple health outcomes, the association between positivity and mortality should be weaker for low-preventable versus high-preventable causes of death. In addition, because advancing age itself my represents a condition in which little can be done to delay death, it is reasonable to assume nonlinear positivity effects with age, with positivity differences in mortality being substantially reduced at the very end of life.

CONCLUSION

A substantial body of research suggests that despite declines in cognitive resources, emotional well-being is well preserved in old age. In this article, we focus on what is currently known regarding the health significance of positive emotions in adulthood and later life, giving emphasis to theoretical predictions, underlying mechanisms, and methodological gaps that currently exist in the literature. Although there is growing support for the importance of positive emotions in later life, full understanding of the phenomenon is far from complete. Questions remain concerning age-differences in the regulation, physiological manifestation, and optimal level of positive emotion. More research is also needed to clarify the role of personality traits in the emotion-health association, as emotion-laden traits such as neuroticism have emerged as important predictors of health outcomes, especially mortality (Mroczek & Spiro, 2007; Mroczek, Spiro, & Turiano, 2009). To the extent that progress can be made on these issues, research on emotional aging may begin to create theoretically informed links to other literatures currently attempting to probe the health significance of positive emotions.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG023571, R21AG026365). We extend thanks to Derek Isaacowitz, Corinna Löckenhoff, and Gary Evans for helpful comments on a previous version of this article.

References

- Adler N, Matthews N. Health psychology: Why do some people get sick and some stay well? Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:229–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby F, Isen AM, Turken AU. A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychological Review. 1999;106:529–550. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes MM, Baltes PB, editors. Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom HG, Ahmed I, Alessi CA, Ancoli-Israel S, Buysse DJ, Kryger MH. Evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and management of sleep disorders in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:761–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Butow PN, Culjak G, Coates AS, Dunn SM. Psychosocial predictors of outcome: Time to relapse and survival in patients with early stage melanoma. British Journal of Cancer. 2000;83:1448–1453. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Kuhn CM, Siegler IC, Williams RB. Positive affect is associated with cardiovascular reactivity, norepinephrine level and mornign rise in salivary cortisol. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:862–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB. A four-factor model of perceived control: Avoiding, coping, obtaining, and savoring. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:773–797. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB. Savoring beliefs inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. Journal of Mental Health (UK) 2003;12:175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Charles ST. Emotion in the second half of life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1998;7:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels J. At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA, Mather M. Handbook of the psychology of aging. Sixth ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation and emotion. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin R, et al. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST. Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:1068–1091. doi: 10.1037/a0021232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;61:383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:310–324. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR. Memories of social interactions: Age differences in emotional intensity. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:300–309. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR, Luong G, Almeida DM. Now you see it, now you don’t: Age differences in affective reactivity to social tensions. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:645–653. doi: 10.1037/a0016673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Reynolds CA, Gatz M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:136–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ, Treanor JJ. Positive emotional style predicts resistance to illness after experimental exposure to rhinovirus or influenza A virus. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:809–815. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000245867.92364.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Stress and infectious disease in humans. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:5–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Zonderman AB, McCrae RR, Cornoni-Huntley J, Locke B, Barbano HE. Longitudinal analyses of psychological well-being in a national sample: Stability of mean levels. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1987;42:50–55. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devins GM, Mann J, Mandin H, Paul LC, Hons RB, Burgess ED. Psychosocial predictors of survival in end-stage renal disease. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990;178:127–133. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences. 2004;359:1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Losada MF. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist. 2005;60:678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, Tugade MM. The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion. 2000;24:237–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1010796329158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Ram N, Mayraz G, Hidajat M, Lindenberger U, Wagner GG, et al. Late-life decline in well-being across adulthood in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States: Something is seriously wrong at the end of life. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:477–485. doi: 10.1037/a0017543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin PW, Mroczek DK, Spiro A. Variability in affective change among aging men: Longitudinal findings from the VA Normative Aging Study. Journal of Research in Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:942–965. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Stress and the aging immune system. Brain, Behavior and Immunity. 2004;18:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Goren D, Wilson HR. Looking while unhappy: Mood congruent gaze in young adults, positive gaze in older adults. Psychological Science. 2008;19:848–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Neupert SD. Use of gaze for real-time mood regulation: Effects of age and attentional functioning. Psychology & Aging. 2009;24:989–994. doi: 10.1037/a0017706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion. 2006a;6:511–516. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Selective preference in visual fixation away from negative images in old age? An eye-tracking study. Psychology & Aging. 2006b;21:40–48. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen AM. Some ways in which positive affect influences decision making and problem solving. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. 3rd ed. New York: Guildford Press; 2008. pp. 548–573. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Q, Mather M, Carstensen LL. The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical Memory. Psychological Science. 2004;15:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.01503011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Stress and immunity: Age enhances the risks. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: New perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:83–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Seymour TL, Gaunt JT, Baker C, Nesmith K, Mather M. Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion. 2007;7:705–714. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok BE, Catalino LI, Fredrickson BL. The broadening, building, buffering effects of positive emotions. In: Lopez SJ, editor. Positive psychology: Exploring the best of people: Capitalizing on emotional experiences. Vol. 3. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company; 2008. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U, Little TD, Smith J. Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudional evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:511–526. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G. Dynamic integration: Affect, cognition, and the self in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G, Diehl M, Jain E, Zhang F. Six-year change in affect optimization and affect complexity across the adult life span: A further examination. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:738–751. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G, Medler M. Affect optimization and affect complexity: Modes and styles of regulation in adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:571–587. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Aging, emotion, and health-related decision strategies: Motivational manipulations can reduce age differences. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:134–146. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Pressman SD, Cohen S. Positive affect and immune function. In: Ader R, editor. Psychoneuroimmunology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. San Diego: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 761–779. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science. 2003;14:409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Johnson MK. Affective review and schema reliance in memory in older and younger adults. American Journal of Psychology. 2003;116:169–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Larkin GR, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Carstensen LL. Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: Changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychology & Aging. 2005;20:542–553. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK. Age and emotion in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK. Positive and negative affect at midlife. In: Ryff CD, Brim OG, editors. How healthy are we?: A national study of well being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A. Personality change influences mortality in older men. Psychological Science. 2007;18:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A, Turiano NA. Do health behaviors explain the effect of neuroticism on mortality? Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD. Pathways linking positive emotion and health in later life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Allaire JC. Cardiovascular intraindividual variability in later life: The influence of social connectedness and positive emotions. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:476–485. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. The role of daily positive emotions during conjugal bereavement. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59B:P168–P176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace K. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Boker SM. Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1777–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Burrow AL. The social broadening effects of positive emotons. Unpublished manuscript. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Bonanno GA. Prospective predictors of positive emotions following spousal loss. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:653–660. doi: 10.1037/a0018870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Bonanno GA, Almeida D. Spousal loss predicts alterations in diurnal cortisol activity through prospective changes in positive emotion. Health Psychology. 2011;30:220–227. doi: 10.1037/a0022262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Isen AM. Positive emotions attenuate age differences in cardiovascular responses following laboratory stress. Unpublished manuscript. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Mroczek DK. Aging, positivity, and mortality. Unpublished manuscript. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ostir GV, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS. Onset of frailty in older adults and the protective role of positive affect. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:402–408. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Carstensen LL. Age and emotional experience during mutual reminiscing. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:430–442. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering TG, Gerin W. Cardiovascular reactivity in the laboratory and the role of behavioral factors in hypertension: A critical review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1990;12:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M. Age differences in perceived positive affect, negative affect, and affect balance in middle and old age. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2001;2:375–405. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe S, Carstensen LL. Emotional aging: Recent findings and future directions. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2010;65:135–144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota M, Levenson RW. Effects of aging on experimentally instructed detached reappraisal, positive reappraisal, and emotional behavior suppression. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0017896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Dockray S, Wardle J. Positive affect and psychobiological processes relevant to health. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1747–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, O'Donnell K, Marmot M, Wardle J. Positive affect, psychological well-being, and good sleep. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008;64:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, O’Donnell K, Badrick E, Kumari M, Marmot MG. Neuroendocrine and inflammatory factors associated with positive affect in healthy men and women: Whitehall II study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167:96–102. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Wardle J, Marmot M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardivascular, and inflamatory processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:6508–6512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Deaton A. A snapshopt of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir M, John OP, Srivastava S, Gross JJ. Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:731–744. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Regulation of positive emotions: Emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2007;8:311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Birmingham W, Berg C. Are older adults less or more physiologically reactive? A meta-analysis of age-related differences in cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory tasks. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2010;65B:154–162. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in older age. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Wadlinger HA, Isaacowitz DM. Fixing our focus: Training attention to regulate emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15:75–102. doi: 10.1177/1088868310365565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh CE, Fredrickson BL. Nice to know you: Positive emotions, self-other overlap, and complex understanding in the formation of a new relationship. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1:93–106. doi: 10.1080/17439760500510569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh CE, Fredrickson BL. Nice to know you: Positive emotions, self-other overlap, and complext understanding in the formation of a new relationship. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1:93–106. doi: 10.1080/17439760500510569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JV, Heimpel SA, Michela L. Savoring versus dampening: Self-esteem differences in regulating positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:566–580. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm LH, Labouvie-Vief G, Aycock J, Rebucal KA, Koch HE. Performance in auditory and visual emotional Stroop tasks: A comparison of younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:523–535. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Johnson LM, Davis MC. Positive affect as a source of resilience for women in chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:212–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Smith B, Affleck G, Tennen H. Examinations of chronic pain and affect relationships: Applications of a dynamic model of affect. 2001 doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]