Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study were to determine: 1) the kinematic effect of subtotal medial meniscectomy on ACL deficient knee and 2) the effect of ACL reconstruction on kinematics of the knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy under an anterior tibial and a simulated quadriceps loads.

Methods

Eight human cadaveric knees were sequentially tested using a robotic testing system under 4 conditions: intact, ACL deficiency, ACL deficiency with subtotal medial meniscectomy, and single bundle ACL reconstruction using a bone-patellar tendon-bone graft. Knee kinematics were measured at 0°, 15°, 30°, 60°, and 90° of flex ion under an anterior tibial load of 130 N and a quadriceps muscle load of 400 N.

Results

Subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knee significantly increased anterior and lateral tibial translations under the anterior tibial and quadriceps loads (P < 0.05). These kinematic changes were larger at high flexion (≥ 60°) than at low flexion angles. ACL reconstructio n in knees with ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy significantly reduced the increased anterior tibial translation, but could not restore anterior translation to the intact level with differences ranging from 2.6 mm at 0° to 5.5 mm at 30° of flexion. ACL reconstruction did not significantly affect the medial-lateral translation and internal-external tibial rotation in the presence of subtotal meniscectomy.

Conclusions

Subtotal medial meniscectomy in knees with ACL deficiency altered knee kinematics, especially at high flexion angles. ACL reconstruction significantly reduced the increased tibial translation in knees with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy, but could not restore the knee kinematics to the intact knee level.

Clinical Relevance

This study suggests that meniscus is an important secondary stabilizer against anterior and lateral tibial translations and should be preserved in the setting of ACL reconstruction for restoration of optimal knee kinematics and function.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament, knee kinematics, reconstruction, subtotal medial meniscectomy

INTRODUCTION

The loss of part or the entire meniscus alters the mechanics of the knee and its function, leading to cartilage deterioration and osteoarthritis of the joint.1–4 Although lateral meniscal deficiency is more deleterious than medial meniscal deficiency for the joint,5,6 medial meniscal injuries are more frequent than lateral meniscus in patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.7–11 Biomechanical studies have identified how increased knee joint forces contribute to functional impairment and early onset of osteoarthritis in the knee with combined ACL and medial meniscus injuries.12–14 It has also been shown that meniscus plays a greater role in contributing to the stability in an ACL deficient knee than in an ACL intact knee.12,13

Although meniscal preservation in ACL reconstruction in knee with combined ACL and medial meniscus injuries have the theoretical advantage of being protective to the articular cartilage, meniscectomy remains necessary for irreparable meniscal tears. In several clinical studies, ACL reconstruction with meniscectomy in combined ACL and meniscus injured knees has been reported to result in significant pain relief and functional improvement regardless of meniscal status.10,15–17 However, there are still debates on whether ACL reconstruction with meniscectomy in combined ACL and meniscus injuries can restore the antero-posterior stability to the intact knee level. Few biomechanical studies have quantitatively investigated the effect of the ACL reconstruction on knee kinematics in combined ACL and meniscus deficient knees.18

Hence, the purposes of this study were to determine the effect of subtotal medial meniscectomy on ACL deficient knee kinematics and to quantify the effect of ACL reconstruction on kinematics of the knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy under anterior tibial and muscle loading conditions. We hypothesized that the subtotal medial meniscectomy affects the kinematics of ACL deficient knee more at high flexion angles than at low flexion angles. We further hypothesized that ACL reconstruction in knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy can restore anterior tibial translation to the intact knee level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eight fresh-frozen cadaveric human knee specimens from 6 male and 2 female donors with an average age of 60 years (ranges, 59 to 64 years) were used in this study. The specimens had been stored at −20°C prior to the testing and had been thawed at room temperature for 24 hours before the experiment was conducted. Each specimen was examined for osteoarthritis and ACL injury using fluoroscopy and manual stability test. Specimens with either of these conditions were not used in this study. The femur and tibia were truncated approximately 25 cm from the joint line, with all the soft tissues (skin, knee ligaments, joint capsule, and musculature) around the knee intact. A bone screw was used to firmly secure the fibula to the tibia in its anatomical position. To facilitate the fixation of the femur and tibia, musculature surrounding the shafts was striped. The tibial and the femoral shafts were then secured in thick-walled aluminum cylinders using bone cement.

A robotic testing system that can be operated under force and displacement control modes was used to study the knee biomechanics.19–21 The testing system consists of a robotic manipulator (Kawasaki Heavy Industry, Japan) and a 6 degrees of freedom load cell (JR3 Inc., CA). Each specimen had been preconditioned manually by flexing the knee 10 times through its range of motion from full extension to full flexion before it was installed on the robotic testing system. After installing the specimen on the testing system, the coordinate systems of the joint were defined as previously described.19,22 The quadriceps muscles were attached to a rope using sutures and the rope was passed through a pulley system mounted on the femoral clamp. In order to simulate quadriceps muscle loading, weights were hanged on the free end of the rope.

The robotic testing system was used to determine a passive flexion path of the knee in unloaded condition. The passive position is described as a position of the knee at which all resultant forces and moments at the knee center were minimal (< 5 N and 0.5 N·m, respectively). The passive positions were determined from 0° to 90° in 1° increments of knee flexion. These passive positions of the knee at each flexion angle were combined to describe the passive path of the knee between 0° to 90° of knee flexion. First, an anterior tibial load of 130 N was applied to the knee at selected flexion angles of 0°, 15°, 30°, 60°, and 90° along the passive flexion path. Next, a quadriceps muscle load of 400 N was independently applied to the knee at the same selected flexion angles. The anterior load simulated clinical examinations such as the Lachman and anterior drawer tests. The quadriceps muscle loading was applied parallel to the femur shaft to simulate isometric extension of the knee. Under each of these loads, the robot manipulated the knee joint in five degrees of freedom (with a constant selected flexion angle) until the applied forces were balanced by the knee. This position of the knee represented the kinematic response of the knee to the applied loads.

After determination of kinematics in the intact knees, the ACL was transected through a small medial arthrotomy to represent an ACL deficient condition. The arthrotomy and the skin were then repaired in layers by sutures. The kinematics of the ACL deficient knee under the anterior tibial and quadriceps loads was measured again in the same manner as in the intact knee at each selected flexion angle.

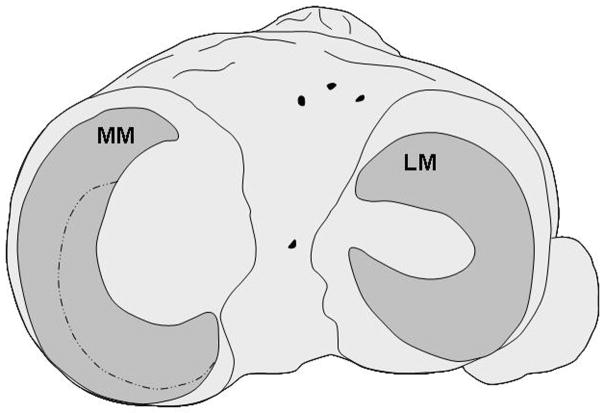

Subtotal resection of the medial meniscus, removing the inner 80% of the body and posterior horn, was performed through a 3 cm long vertical incision posterior to the medial collateral ligament in a fashion described in previous studies (Figure 1).12,14 Care was taken not to damage the posterior oblique ligament, which is important for the rotational and posterior stability.23,24 The incision was then carefully closed in layers. The kinematics of knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy was determined under anterior tibial and quadriceps loads.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the subtotal medial meniscectomy. MM, medial meniscus; LM, lateral meniscus; –--–-, line of subtotal meniscectomy

In the next step, the ACL was reconstructed using a two-incision technique as previously reported.25 A 10 mm wide bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) graft was used for ACL reconstruction, which was harvested from the same specimen. The tibial tunnel was made 7 mm anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and the femoral tunnel was made at 11 or 1 o’clock position of the lateral femoral condyle. The femoral bone plug was fixed using an interference screw through lateral skin incision. Following the posterior tibial load of 40 N, the tibial bone plug was also secured with an interference screw at full extension with 40 N of axial graft tension. The arthrotomy and the skin were then repaired using sutures and the kinematics of the ACL reconstructed knee with subtotal medial meniscectomy was determined using the same protocol as described above. This protocol allowed us to compare the kinematics of the same knee in four different conditions.

Since the study was designed for a within-subjects analysis of knee kinematics on the same knee under the four different conditions, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to detect statistically significant differences in kinematics of the knee among the four different conditions. We also used a repeated measures ANOVA test to determine the effect of knee flexion angles on kinematics. When significant differences were found, paired comparisons were made using the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of ACL deficiency on the kinematics in the meniscus intact knee

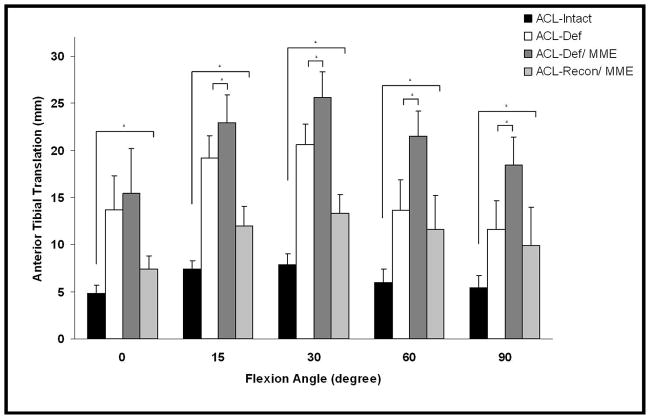

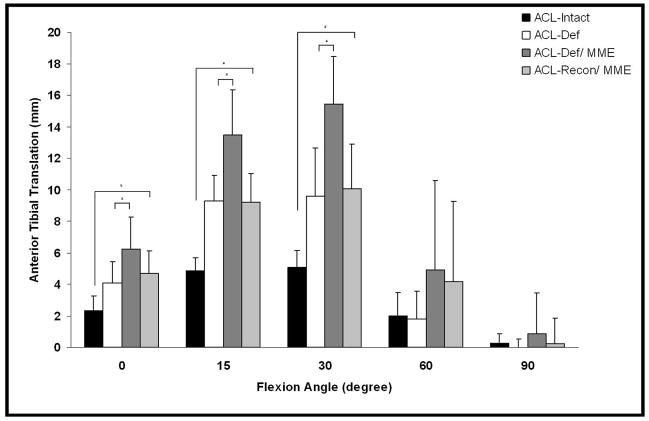

The anterior tibial translation under the anterior tibial load in ACL deficient knee was significantly larger than in the intact knee at all selected flexion angles (P < 0.05). The anterior tibial translation of the ACL deficient knee increased until 30° of flexion and decreased thereafter (Table 1 and Figure 2). Under the muscle load, anterior tibial translation in the ACL deficient knee was larger than the intact knee at 0° to 30° of flexion (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Average increase percentages of anterior tibial translations in different conditions from intact knee under anterior tibial load.

| Flexion angles | ACL-Def | ACL-Def/MME | ACL-Recon/MME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0° of flexion | 186.20% | 221.13% | 54.52% |

| 15° of flexion | 157.56% | 207.61% | 61.05% |

| 30° of flexion | 162.85% | 226.63% | 70.30% |

| 60° of flexion | 126.79% | 257.89% | 93.15% |

| 90° of flexion | 116.62% | 242.78% | 83.11% |

Abbreviation: Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy.

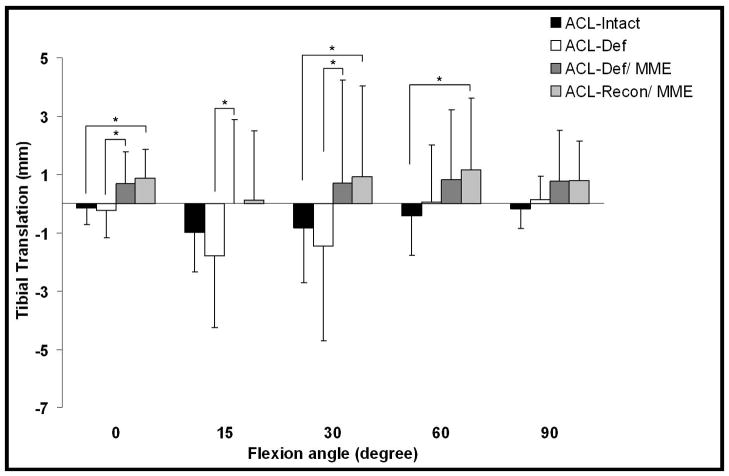

Figure 2.

Anterior translation of the tibia under the anterior load in the four different conditions. Statistical significances were noted between ACL-Intact and ACL-Def as well as ACL-Def/MME and ACL-Recon/MME at all flexion angles. * Represent statistical significance (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SD. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy

Figure 3.

Anterior translation of the tibia under the muscle load in the four different conditions. Statistical significances were noted between ACL-Intact and ACL-Def as well as ACL-Def/MME and ACL-Recon/MME at 0° to 30° of flexion.* Represent statistical significance (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SD. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy

Effect of subtotal medial meniscectomy on the kinematics in ACL deficient knee

Subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knee resulted in an additional increase of anterior tibial translation at all flexion angles except 0° under anterior tibial load (P < 0.05). These increases of anterior tibial translations were different depending on the flexion angle from a minimum 1.4 ± 1.0 mm at 0° to a maximum 7.4 ± 3.3 mm at 60° of flexion, and 6.4 ± 2.7 mm at 90° of flexion (Figure 2). Under the muscle load, subtotal medial meniscectomy in the ACL deficient knee showed similar effect on anterior translation as under the anterior load, but only at the low flexion angles (0° to 30°) (Figure 3).

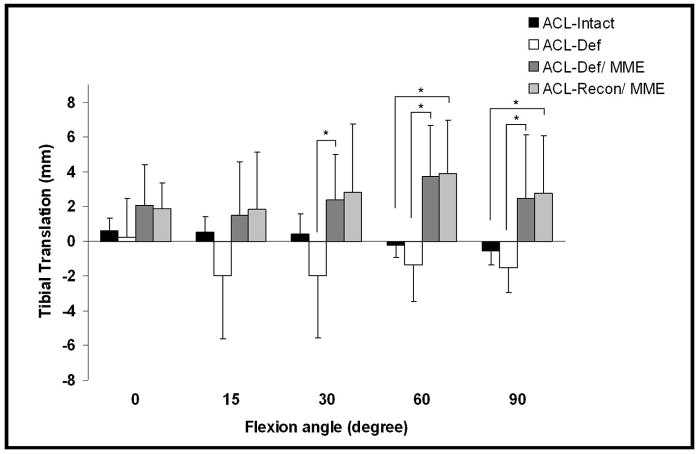

The tibia of the knee with subtotal medial meniscectomy significantly shifted laterally from 30° to 90° of flexion with a maximum of 4.8 ± 3.2 mm at 60° of flexion under anterior tibial load (P < 0.05). These changes in medial-lateral translation after meniscectomy were significant at high flexion (≥ 60°) than at low flexion angles (≤ 15°) (Figure 4). Under the muscle load, the tibia significantly shifted laterally at 0° to 60° of flexion after subtotal medial meniscectomy (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Medial (−)/Lateral (+) translation of the tibia under the anterior load in the four different conditions. * Represent statistical significance (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SD. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy

Figure 5.

Medial (−)/Lateral (+) translation of the tibia under the muscle load in the four different conditions. * Represent statistical significance (P < 0.05). Error bars represent SD. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy

Internal tibial rotation under the anterior load after subtotal medial meniscectomy slightly decreased at all selected flexion angles, showing no statistical significant differences (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Under the muscle load, no significant changes in the pattern of internal rotation were detected (P >0.05) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mean (±SD) values of internal (−)/external (+) rotation of tibia under anterior tibial load in four different conditions. There were no significant differences between the groups at all selected flexion angles

| Flexion angles | ACL-Intact | ACL-Def | ACL-Def/MME | ACL-Recon/MME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° of flexion | 0.1 ± 4.0 | −0.6 ± 2.7 | −0.5 ± 2.7 | −1.9 ± 9.3 |

| 15° of flexion | −1.7 ± 5.2 | −2.6 ± 2.5 | −2.0 ± 2.2 | −2.7 ± 11.2 |

| 30° of flexion | −2.3 ± 5.8 | −2.0 ± 3.1 | −0.7 ± 3.4 | −2.4 ± 12.1 |

| 60° of flexion | −2.6 ± 2.4 | −0.8 ± 5.3 | 3.7 ± 7.9 | −0.6 ± 8.6 |

| 90° of flexion | −1.9 ± 2.7 | −1.8 ± 6.1 | 2.1 ± 8.8 | −1.9 ± 6.6 |

Abbreviation: Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy.

Table 3.

Mean (±SD) values of internal (−)/external (+) rotation of tibia under muscle load in four different conditions. There were no significant differences between the groups at all selected flexion angles

| Flexion angles | ACL-Intact | ACL-Def | ACL-Def/MME | ACL-Recon/MME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° of flexion | −3.3 ± 1.6 | −3.3 ± 1.3 | −4.0 ± 3.3 | −3.2 ± 3.4 |

| 15° of flexion | −9.2 ± 2.4 | −9.7 ± 2.6 | −9.0 ± 2.9 | −8.0 ± 4.9 |

| 30° of flexion | −10.4 ± 3.0 | −9.7± 2.5 | −10.4 ± 3.6 | −8.5 ± 6.2 |

| 60° of flexion | −5.6 ± 3.2 | −3.5 ± 3.0 | −6.5 ± 7.7 | −5.2 ± 6.8 |

| 90° of flexion | −1.7 ± 1.4 | −0.8 ± 1.3 | −2.5 ± 4.4 | −1.4 ± 4.8 |

Abbreviation: Def, deficient; Recon, reconstruction; MME, medial meniscectomy.

Effect of ACL reconstruction on the kinematics in the knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy

ACL reconstruction significantly reduced the anterior tibial translation at all flexion angles under the anterior tibial load and at 0° to 30° of flexion under the muscle load (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). This effect was greatest at 30° of flexion under both loads (from 25.6 ± 2.7 mm to 13.3 ± 2.0 mm under the anterior tibial and from 15.4 ± 3.0 mm to 10.1 ± 2.8 mm under the muscle loads) (Figure 2 and 3). However, the anterior translation after ACL reconstruction in the knee with subtotal medial meniscectomy was higher than the intact knee (P < 0.05). The range of this difference under the anterior tibial load was from 2.6 ± 1.0 mm (55% larger than intact knee level) at 0° to 5.5 ± 2.7 mm at 60° of flexion (93% larger than intact knee level) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2 and Table 1).

The medial-lateral translation of the knee after the ACL reconstruction was not shown to be significantly affected under either the anterior tibial load or the muscle load (Figure 4 and 5). The mean value of internal rotation was slightly increased after ACL reconstruction under the anterior tibial load, but was not statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 2). ACL reconstruction did not significantly affect the internal rotation under the muscle loads (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This biomechanical study demonstrated that subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knees increased anterior translation and lateral shift of the tibia. The effects of subtotal medial meniscectomy were larger at higher flexion angles than at lower flexion angles. The ACL reconstruction using a BPTB graft significantly reduced anterior tibial translation at all flexion angles in knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy. However, ACL reconstruction alone was not able to restore the kinematics to the intact level. In addition, no significant improvement was observed in the lateral shift and internal rotation of the tibia after ACL reconstruction.

There are several studies in literature showing the importance of the medial meniscus in limiting anterior tibial translation in response to anterior tibial load in ACL deficient knees.12–14 Our data demonstrated that subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knees increased anterior tibial translation at all flexion angles under the anterior tibial load. That was consistent with previously published studies in the literature.12,13 In an earlier in-vitro study using dynamic knee-stiffness apparatus,26 Levy et al.13 also did not detect significant effect of medial meniscectomy on tibial rotation in ACL deficient knees. Allen et al.12 showed that medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knees decreased internal rotation under the anterior tibial load. Even though our data showed similar trend in tibial rotation after subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knees, no significant effect was observed. However, a quantitative comparison with these studies is difficult since the loading conditions were not directly comparable, since the point of application of the anterior tibial loads may not be consistent among these studies.

The data of this study showed that ACL reconstruction in knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy significantly reduced anterior tibial translation at all flexion angles. However, anterior tibial translation was not restored to the intact level under the anterior load and the muscle load. These data were not consistent with the in-vitro findings of Papageorgiou et al.18 They reported that meniscectomy did not have any significant effects on anterior tibial translation in ACL reconstructed knee. However, their experimental protocol and loading conditions were different from those in our experiment. Their meniscectomy was performed in the ACL reconstructed knee and the knee was tested under a combined 134 N anterior and 200 N axial compressive load. We evaluated the effect of ACL reconstruction in knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal meniscectomy under an anterior tibial load without compressive load to simulate an anterior drawer test. The differences in experimental protocol made a direct comparison difficult.

No previous studies have discussed the effect of subtotal medial meniscectomy in ACL deficient knee on medial-lateral translation of the knee. In this study, we noted that subtotal medial meniscectomy in the ACL deficient knee resulted in a lateral shift of the tibia at high flexion angles (30° to 90°) under the anterior tibial load and at 0° to 30° of flexion under the quadriceps load, indicating that the medial meniscus also resists lateral tibial translation. It has been shown that the altered medial-lateral kinematics might shift the tibiofemoral articular cartilage contact away from the normal articular locations in addition to the increased cartilage-to-cartilage contact after meniscectomy.27 The altered contact biomechanics of the knee resulted from meniscectomy and kinematics alteration may be deleterious to cartilage and possibly initiate degeneration of the joint.28

Tibial rotational and lateral shift patterns were not significantly changed after ACL reconstruction in the knee with ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy. These results suggested that isolated ACL reconstruction may not restore the normal tibio-femoral articular contact kinematics in knees with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy. A future investigation is required to examine the effect of combined ACL reconstruction and meniscus repair on kinematics of the knee with combined ACL deficiency and medial meniscus injury.

This study has certain limitations. We only studied the knee kinematics under an anterior tibial load and a simulated quadriceps load. Other physiological loading conditions, such as axial tibial compression and muscle co-contraction loads, were not investigated. We used an open technique to resect the ACL and to perform medial meniscectomy. Although incision and repair of the arthrotomy were performed carefully to avoid a potential bias from alteration of capsular tension, the open technique, especially postero-medial arthrotomy may potentially affect knee kinematics in rotation and posterior translation.23,24 However, for repeatable resection of specific regions of medial meniscus, it was required to completely visualize the medial meniscus which is not possible in the installed position on the robotic testing system. This technique has been used in other cadaveric studies in the literature.12,14

In this study, we used a reconstruction technique, which has been shown to result in clinically satisfactory anterior stability of the knee with isolated ACL injury in previous studies.10,16,18,22 Therefore, we did not test the effect of ACL reconstruction in restoration of anterior stability of the knee with intact meniscus. This was to avoid reconstruction of the knee twice using the same BPTB graft that may cause graft and tunnel damages. Finally, we did not examine the in situ forces of the ACL and ACL graft. Future studies should investigate the effect of different reconstruction techniques using hamstring graft or double bundle reconstruction on the knee kinematics and in situ forces in the ACL and ACL graft in knees with combined ACL injury and meniscectomy. Nevertheless, this study was the first study that provided quantitative data on the effect of the ACL reconstruction on the kinematics of the knee with combined ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy under anterior tibial and quadriceps loads.

CONCLUSION

The data of this study showed that subtotal medial meniscectomy in an ACL deficient knee caused greater kinematic changes at higher than at lower flexion angles. Subsequently ACL reconstruction in knee with ACL deficiency and subtotal medial meniscectomy was shown to dramatically reduce the increased anterior translation caused by subtotal medial meniscectomy, but could not restore the knee kinematics to the intact knee level. In future, the effect of combined ACL reconstruction and meniscus repair should be investigated to develop an efficient surgical protocol for treatment of the knee with combined ACL deficiency and meniscus injury.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boyd KT, Myers PT. Meniscus preservation; rationale, repair techniques and results. Knee. 2003;10:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(02)00147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairbanks TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30:664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RJ, Kettelkamp DB, Clark W, Leaverton P. Factors affecting late results after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:719–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RE, Smith EC, Reisch JS. Effects of medial meniscectomy in patients older than forty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:783–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hede A, Larsen E, Sandberg H. The long term outcome of open total and partial meniscectomy related to the quantity and site of the meniscus removed. Int Orthop. 1992;16:122–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNicholas MJ, Rowley DI, McGurty D, Adalberth T, Abdon P, Lindstrand A, Lohmander LS. Total meniscectomy in adolescence. A thirty-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church S, Keating JF. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: Timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1639–1642. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B12.16916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fithian DC, Paxton LW, Goltz DH. Fate of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:621–636. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(02)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papastergiou SG, Koukoulias NE, Mikalef P, Ziogas E, Voulgaropoulos H. Meniscal tears in the ACL-deficient knee: correlation between meniscal tears and the timing of ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1438–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery: Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:446–452. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommerlath K, Lysholm J, Gillquist J. The long-term course after treatment of acute anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. A 9 to 16 year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:156–162. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen CR, Wong EK, Livesay GA, Sakane M, Fu FH, Woo SL. Importance of the medial meniscus in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:109–115. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy IM, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The effect of medial meniscectomy on anterior-posterior motion of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoemaker SC, Markolf KL. The role of the meniscus in the anterior-posterior stability of the loaded anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Effects of partial versus total excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shelbourne KD, Stube KC. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-deficient knee with degenerative arthrosis: Treatment with an isolated autogenous patellar tendon ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:150–156. doi: 10.1007/s001670050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett GR, Ruff CG. The effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on symptoms of pain and instability in patients who have previously undergone meniscectomy: a prereconstruction and postreconstruction comparison. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:704–709. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rueff D, Nyland J, Kocabey Y, Chang HC, Caborn DN. Self-reported patient outcomes at a minimum of 5 years after allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with or without medial meniscus transplantation: an age-, sex-, and activity level-matched comparison in patients aged approximately 50 years. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1053–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papageorgiou CD, Gil JE, Kanamori A, Fenwick JA, Woo SL, Fu FH. The biomechanical interdependence between the anterior cruciate ligament replacement graft and the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:226–231. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Gill TJ, DeFrate LE, Zayontz S, Glatt V, Zarins B. Biomechanical consequences of PCL deficiency in the knee under simulated muscle loads - an in vitro experimental study. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:887–892. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Papannagari R, DeFrate LE, Yoo JD, Park SE, Gill TJ. The effects of ACL deficiency on mediolateral translation and varus-valgus rotation. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:355–360. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, Rudy TW, Sakane M, Kanamori A, Ma CB, Woo SL. The importance of quadriceps and hamstring muscle loading on knee kinematics and in-situ forces in the ACL. J Biomech. 1999;32:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo JD, Papannagari R, Park SE, DeFrate LE, Gill TJ, Li G. The effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on knee joint kinematics under simulated muscle loads. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:240–246. doi: 10.1177/0363546504267806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen W, Loerch S, Schanz S, Raschke M, Zantop T. The role of the posterior oblique ligament in controlling posterior tibial translation in the posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:495–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546507310077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson JR, Bull AM, Thomas RR, Amis AA. The role of the medial collateral ligament and posteromedial capsule in controlling knee laxity. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1815–1823. doi: 10.1177/0363546506289433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill TJ, Steadman JR. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction the two-incision technique. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:727–735. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(02)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukubayashi T, Torzilli PA, Sherman MF, Warren RF. An in vitro biomechanical evaluation of anterior-posterior motion of the knee. Tibial displacement, rotation, and torque. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:258–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Moses JM, Papannagari R, Pathare NP, DeFrate LE, Gill TJ. Anterior cruciate ligament deficiency alters the in vivo motion of the tibiofemoral cartilage contact points in both the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1826–1834. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhari AM, Briant PL, Bevill SL, Koo S, Andriacchi TP. Knee kinematics, cartilage morphology, and osteoarthritis after ACL injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:215–222. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815cbb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]