Abstract

This study investigated the reciprocal effects between teacher student relationship quality (TSRQ) and two dimensions of classroom peer relatedness, peer liking and peer academic reputation (PAR), across three years in elementary school and the effect of both TSRQ and the peer relatedness dimensions on academic self efficacy. Participants were 695 relatively low achieving, ethnically diverse students recruited into the longitudinal study when they were in first grade. Measures of TSRQ and peer relatedness were assessed in years/grades 2-4. Peer liking and PAR were moderately correlated with each other at each time period. As expected, peer liking and TSRQ exhibited bidirectional effects across the three years. Year 3 TSRQ had an effect on Year 4 PAR, but PAR did not have an effect on TSRQ at either time interval. In an additional analysis, Year 4 PAR mediated the effect of Year 3 TSRQ on Year 5 academic self efficacy. Implications for teacher professional development are discussed.

Children who begin school with low academic readiness skills are at risk for continued academic difficulties including poor grades, grade retention, and leaving school prior to graduation (Alexander, Entwisle, & Horsey, 1997; Reynolds & Bezruczko, 1993). Low academic performance is predictive of later behavioral and social problems during school and negative economic and mental health outcomes in adulthood (Barrington & Hendricks, 1989; Orfield, Losen, Wald, & Swanson, 2004; Roeser, Eccles, & Freedman-Doan, 1999). An extensive body of literature documents that achievement disparities between Black or Latino students and White students and between socioeconomic groups are present in the early grades and persist throughout schooling (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; Harris & Herrington, 2006; Leventhall & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Given these educational disparities and the importance of early achievement to long-term adjustment, researchers have sought to identify factors that impact children’s early achievement trajectories (for review see The Future of Children, 2005). This research has identified social relationships within classrooms as important aspects of the early classroom context that have implications for children’s academic as well as social and behavioral adjustment (for reviews see Bierman, 2004; Ladd, 1999; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Hamre & Pianta, 2006).

Classrooms are, by definition, social contexts. Students’ interactions with teachers and classmates impact their social and emotional adjustment as well as their academic motivation and learning (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Hughes & Kwok, 2007; Wentzel, 1999). Affectively positive and supportive relationships with teachers and classmates promote a sense of school belonging and a positive student identity (Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Connell & Wellborn, 1991), which engender the will to participate cooperatively in classroom activities and to try hard and persist in the face of challenges (Anderman & Anderman, 1999; Birch & Ladd, 1997; Hughes, Luo, Kwok, & Loyd, 2008; Skinner & Belmont, 1993). Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that minority and low income students as well as students with low readiness skills may be especially responsive to differences in the quality of classroom social relationships (Baker, 2006; Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002; Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Meehan, Hughes, & Cavell, 2003). Unfortunately, these same students are least likely to be enrolled in elementary classrooms with a positive social-emotional climate (Pianta et al., 2007).

To date, research on teacher-student interactions and research on peer relationships have largely progressed along separate lines. With a few exceptions (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Mercer & DeRosier, 2008; Zimmer-Gembeck, Chipuer, Hanisch, Creed, & McGregor, 2006), researchers have rarely investigated how these two types of social relationships in classrooms may affect each other over time or their joint contributions to children’s school adjustment. his study fills this gap by testing the reciprocal effects of teacher-student relationship quality and classroom peer relationships from grades 2 to 4 as well as the contribution of both types of relationship to students’ academic self-efficacy in grade 5. The study was designed to test for cross-domain effects among teacher student relationships and peer relationships while controlling for both within-time associations and rank-order stability of each domain over time. Direct and meditational pathways between the two domains and subsequent academic self-efficacy are also investigated. A better understanding of the linkages between the two social domains and academic self efficacy would permit more focused teacher preparation and professional development efforts to utilize the teacher-student relationship to promote students’ academic success. Next, literature on the effects of teacher-student relationships and of peer relationships on students’ school adjustment is summarized, followed by a review of literature on the unique and shared contributions of both types of relationships to adjustment and their linkages with each other.

Teacher-student relationships and school adjustment

Many benefits accrue to children who experience a supportive, positive relationship with their teachers, including effortful and cooperative engagement in the classroom, (Hughes & Kwok, 2007; Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999; Meehan et al., 2003; Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, 1998), peer acceptance (Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, 2001; Hughes & Kwok, 2006), and academic achievement (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hughes, Luo, Kwok, & Loyd, 2008). Conversely, students whose relationships with teachers are characterized by conflict are more likely to drop out of school, be retained in grade, experience peer rejection, and to increase externalizing behaviors (Ladd et al., 1999; Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005). The benefits of a supportive, low-conflict relationship with one’s teacher are evident from the earliest school years (Ladd et al., 1999; Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994) through adolescence (Ryan, Stiller, & Lynch, 1994; Wentzel, 1998).

Although the teacher-student relationship is important at all ages, early relationships may be especially important to long-term adjustment. Hamre and Pianta (2001) found an effect for teacher-student relationship conflict assessed in first grade on achievement seven years later, controlling for relevant baseline child characteristics. According to developmental system theory (Lerner, 1998), factors that influence early success may have an “out sized” effect on longer-term outcomes through dynamic reciprocal causal processes. Consistent with this view, in a three-year longitudinal study of first grade students from the longitudinal sample for the current study, Hughes et al. (2008) found evidence of reciprocal causal effects between teacher-student relationship quality and student effortful engagement. Both processes contributed to students’ academic trajectories.

Peer relationships and school adjustment

Researchers investigating linkages between classroom peer relationships and academic outcomes have investigated various dimensions of peer relatedness, including one’s level of peer acceptance/liking (Ladd et al., 1999 Furrer and Skinner, 2003), peer rejection or victimization (Buhs, 2005), the number and characteristics of one’s friends (Altermatt & Pomerantz, 2003; Kindermann, 2003), and one’s reputation within the peer group on various characteristics such as popularity, aggression, or academic competence (Gest, Domitrovich, & Welsh, 2005; Risi, Gerhardstein, & Kistner, 2003). The most extensively studied aspect of peer relationships is one’s level of peer acceptance/liking versus rejection (for review see Bierman, 2004; Ladd, 1990). Studies utilizing longitudinal designs and appropriate statistical controls have found an effect of peer acceptance on academic achievement in the elementary grades (Ladd et al., 1999; Buhs, Ladd, & Herald, 2006; Diehl et al., 1998). Furthermore, the effect of peer acceptance on achievement appears to be mediated, at least in part, by the effect of peer acceptance/rejection on students’ academic self efficacy beliefs (Buhs, 2005; Flook, Repetti, & Ullman, 2005; Thijs & Verkuyten, 2008).

Most researchers investigate a single dimension of peer relatedness. Because various dimensions of peer relatedness covary (Cole, Maxwell, & Martin, 1997; Gest et al., 2005; Hennington, Hughes, Cavell, & Thompson, 1998), failure to simultaneously investigate multiple dimensions may result in misattributing an effect to one dimension when an omitted dimension is responsible for the effect. In a short-term longitudinal study of kindergarten children, Ladd, Kochenderfer, and Coleman (1997) found different dimensions make both shared (redundant) and non-shared (unique) contributions to different adjustment outcomes.

Recently researchers have investigated the joint contribution of peer academic reputation (PAR) and peer acceptance/liking to students’ academic self efficacy and achievement (Gest et al., 2005; Hughes, Dyer, Luo, & Kwok, 2009). PAR refers to the collective judgment of one’s classmates regarding one’s academic competence and is assessed by asking students to nominate classmates who meet one or more descriptors of an academically competent student. A student’s score is the number of nominations on items assessing peers’ perceptions of academic ability (e.g., best in reading, best in math). According to symbolic interactionist theory (Harter, 1998; Mead, 1934), students are expected to incorporate others’ views of their abilities into their self-appraisals. Consistent with this reasoning, PAR predicted changes in elementary students’ academic self efficacy beliefs, above peer liking as well as teacher ratings of students’ abilities (Hughes et al., 2009). The current study investigates the within and cross-year relationships between these two dimensions of peer relatedness and teacher-student relationship quality as well as evidence that peer relatedness variables mediate the effect of TSRQ on academic self efficacy..

Joint effects of teacher student relationship quality and peer relatedness to school adjustment

Studies investigating both domains of classroom relatedness report small to moderate cross-sectional (i.e., within wave) associations between teacher student relationship quality (TSRQ) and peer acceptance or rejection (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2006; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Goodenow, 1993; Ladd et al., 1999; Wentzel, 1998), which may be the result of child characteristics that influence each relationship domain as well as contextual features of the classroom. Most studies investigating the joint effects of TSRQ and peer relatedness on adjustment have produced inconsistent effects and are limited in their ability to test for directional effects of relationship variables on adjustment because they have not controlled for prior level of the adjustment outcome. An exception is a longitudinal study utilizing growth modeling (Gruman, Harachi, Abbott, Catalano, & Fleming, 2008) that investigated the shared and unique effects of student-perceived teacher support and teacher-rated peer acceptance (modeled as time-varying covariates) on the growth trajectories on students in grades 2-5. Results differed by adjustment outcomes. Year-to-year improvement in both teacher support and peer acceptance (relative to students’ own scores across time) predicted improvements in children’s attitude to school. Only year-to-year improvements in perceived teacher support predicted improvements in children’s teacher-rated classroom participation, whereas only year-to year changes in peer acceptance predicted changes in academic performance (a finding that could be due to shared method variance, due to the fact that teachers rated both peer acceptance and academic achievement). These results suggest that both dimensions of children’s classroom social relationships contribute to positive school trajectories but that the relative importance of each varies as a function of the particular adjustment outcome (see also Cole, 1991 and Mercer and DeRosier, 2008).

Reciprocal Effects between TSRQ on Peer relatedness

Drawing from bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006), which views development as the result of an individual’s transactions within and across multiple systems, we expect that relationships in one domain influence relationships in the other domain. Specifically, we expect that when students experience supportive interactions with teachers, classmates view them more positively; similarly, positive peer relationships may engender cooperative participation in the classroom and improved teacher-student interactions. Thus social ties in one domain may have consequences for social ties in the other domain. Next we summarize evidence for each reciprocal path.

TSRQ → Peer relatedness

Considerable research documents that adults play a central role in shaping children’s social cognitions, including their perceptions of peers (Corsaro & Eder, 1990; Weiner, Graham, Stern, & Lawson, 1982). The metaphor of the invisible hand (Farmer, this issue) refers to the impact of teachers’ everyday interactions in the classroom, including instructional and non-instructional interactions, on the classroom social structure. According to this reasoning, students’ perceptions of teacher-child interactions may serve as an affective bias that influences how they view the child on multiple dimensions (Hymel, 1986; White & Kistner, 1992). Hughes et al. (2001) argued that in elementary classrooms the teacher serves as a social referent for children such that classmates make inferences about children’s attributes and likeability based, in part, on their observations of teacher-student interactions. “Students may have more opportunities to observe teacher-student interactions with a given child than to interact directly with the child or to observe the child’s interactions with peers… The quality of that teacher-student interaction becomes part of the shared information classmates have about that child, thereby promoting a group consensus about the child’s attributes” (p 292). In a sample of third and fourth grade children, consistent with expectations, Hughes et al. found that peers’ perceptions of the teacher-student relationship predicted classmates’ liking for students above peers’ and teachers’ evaluations of children’s aggression (a strong predictor of peer liking).

Additional evidence for a causal role for teacher-student relationships on peer relationships comes from analogue experimental studies in which teacher positive and negative interactions with children influenced students’ liking for and perceptions of that child’s morality and academic behaviors (White & Kistner, 1992; White, Sherman, & Jones, 1996).Classroom-based experimental studies in which teacher reinforcement patterns to low-accepted children primary grade children influenced classmates’ liking for them provide additional evidence (Retish, 1973; Flanders & Havumaki, 1960). Prospective observational studies document that teacher student support predicts cross-year improvements in the peer status of rejected children (Taylor, 1989; Taylor & Trickett, 1989). In a study with the current longitudinal sample, TSRQ in first grade predicted changes in children’s peer acceptance the following year (Hughes & Kwok, 2006). The current study is the first to investigate the longitudinal effect of TSRQ on students’ peer academic reputation in the classroom. Consistent with Heider’s balance theory of interpersonal perception (1958) as well as empirical evidence that students attribute positive attributes to students whom they like (Hymel, 1986) or whose interactions with teachers are positive (White & Kistner, 1992), we expect students will attribute greater academic ability to students whose relationships with teachers are higher in support and lower in conflict.

Peer relatedness → TSRQ

The authors know of one study that has investigated the effect of peer relationships on TSRQ (Mercer & DeRosier, 2008). Across grades 3 and 4 peer rejection and teacher liking for children demonstrated reciprocal effects. Because the measure of teacher relationship was a single item asking teachers “How easy is it for you to like this child”, findings may not generalize to a measure of teacher provision of social support to children. The expectation that peer acceptance/rejection influences TSRQ is based on the logic that peer acceptance influences students’ cooperative and effortful engagement in the classroom (Ladd & Buhs, 2000; Ladd et al., 1999; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2006) as well as academic self efficacy (Buhs, 2005; Flook, Repetti, & Ullman, 2005) both of which may, in turn, influence teacher-student interactions (Hughes et al., 2008; Silver et al., 2005; Birch & Ladd, 1997). Similarly, across the elementary grades, peer academic reputation predicts academic self concept, effort, and performance (Hughes et al., 2009; Gest, Rulison, Davidson, & Welsh, 2008). Based on these findings, we expect an effect of both peer acceptance and PAR on TSRQ.

Developmental and sex considerations

The relative influence of TSRQ on the peer relatedness variables may vary by developmental period and by the specific dimension of peer relatedness. We know of no research that has examined developmental changes in the influence of teacher-student relationships on students’ peer relationships. Based on research demonstrating that students increase their reliance on peers for social support as they transition from the elementary grades to middle school (Buhrmeser & Furman, 1987; Cole et al., 1997; Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989), one might expect the influence of the teacher-student relationship on peer acceptance would lessen as students enter adolescence. Because the current study does not extend into the middle school grades, we have no reason to expect the cross-year effect of TSRQ on peer acceptance will differ across years. However, within the developmental span of the current study, we expect the cross-year effect of TSRQ on PAR will increase with age. This expectation is based on the reasoning that over the elementary grades students are more likely to use social comparison cues in making inferences about their own and classmates’ abilities (Kuklinski & Weinstein, 2001), and that teacher differential interactions with students are an important source of social comparison cues (Weinstein, Marshall, Sharp, & Botkin, 1987).

Sex is a salient aspect of children’s social relationships. Girls are more likely than boys to experience relationships with teachers that are high in support and low in conflict (Silver et al., 2005; Baker, 2006; Hughes, Zhang, & Hill, 2006), perhaps due to boys’ higher levels of conduct problems or due to the fact that most teachers are female. Furthermore, girls place a higher value on social relationships than do boys (for review wee Crick, Ostrov, & Kawabata, 2007). Girls also report higher levels of perceived academic competence, especially in reading (Marsh, 1989; Saunders, Davis, Williams, & Williams, 2004), and boys and girls differ in the relative importance of different sources of appraisals of competence to different dimensions of perceived competence (Cole & White, 1993). Thus we investigate sex differences on study variables and include sex as a covariate in all tested models. We also test for sex moderation of the structural models.

Study Purposes and Hypotheses

The primary purpose of the study is to increase our understanding of the linkages between two domains of classroom relationships, teacher-student relationships and peer relationships, over grades 2 to 4 as well as their joint influence on students’ academic self efficacy. First we test a model positing within-wave correlations between TSRQ and both dimensions of peer relatedness at each grade as well as cross-year bidirectional effects between TSRQ and both dimensions of peer relatedness (figure 1). We test for stability of within wave correlations as well as invariance of the structural effects across years. Second, we test the effect of TSRQ at grade 3 on grade 5 academic self-efficacy via grade 4 peer relatedness variables. Based on previous research with this same longitudinal sample in grades 2 (Hughes et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009) that found an effect for PAR, but not for peer liking, on student academic self efficacy and subsequent engagement and achievement, we expect grade 4 PAR will mediate the effect of grade 3 TSRQ on grade 5 academic self efficacy (figure 2). Whereas our previous studies demonstrated an effect of PAR on academic self efficacy in the primary grades (grades 2-3), the current study examines this effect at a different developmental period, as children make the transition to middle school (i.e., grades 4 and 5). More importantly, the current study extends our previous findings by investigating the linkages between peer relatedness and teacher-student relationships and their joint influence on students’ academic self efficacy. We reason that the TSRQ influences PAR which, in turn, influences academic self efficacy.

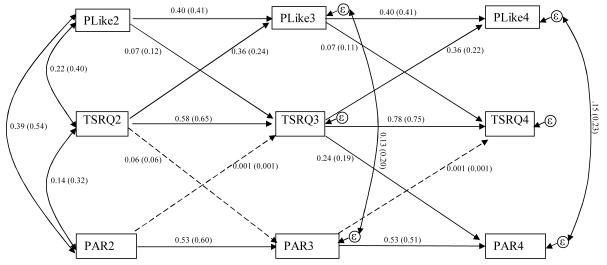

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model for relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and peer liking and peer academic reputation.

Note: Figure 1. Theoretical SEM model for relationship between teacher-student relationship quality and peer liking and peer academic reputation (adjusted for dependence). All constructs are latent variables (see Table 2).χ2 (219) = 366.128 , p < 0.001; CFI = 0.978; root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .031; standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = .039. We controlled for sex, econ1r, IQ for each latent variable; to reduce the complexity of the figure, these variables were not included in the figure. Values are unstandardized parameter estimates (N = 695), with standardized estimates in parentheses, based on the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure using the maximum likelihood estimator. TSRQ: Teacher Student Relationship Quality; PLike: Peer Liking; PAR: Peer Academic Reputation.

The dashed paths indicate non-significant effects.

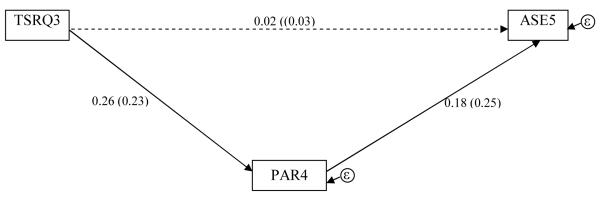

Figure 2.

Hypothesized model for influence of teacher-student relationship quality, peer liking and peer academic reputation on Engagement and Achievement.

Note: Figure 2. Theoretical SEM mediation model for relationship between teacher-student relationship quality, peer academic reputation, and academic self-efficacy (adjusted for dependence). All constructs are latent variables (see Table 2).χ2 (47) = 69.850 , p = .017; CFI = 0.990; root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .027; standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = .029. We controlled Wave 2 baseline scores for each endogenous latent variable; to reduce the complexity of the figure, these variables were not included in the figure. Values are unstandardized parameter estimates (N = 695), with standardized estimates in parentheses, based on the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure using the maximum likelihood estimator. TSRQ: Teacher Student Relationship Quality; PAR: Peer Academic Reputation; ASE: Academic Self-Efficacy.

The dashed paths indicate non-significant effects.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 695 (53% male) first-grade children attending one of three school districts (1 urban, 2 small city) in southeast and central Texas, drawn from a sample of 784 children participating in a longitudinal study examining the impact of grade retention on academic achievement. Participants were recruited across two sequential cohorts in first grade during the fall of 2001 and 2002. Children were eligible to participate in the larger longitudinal study if they scored below the median score for their school district on a state approved, district-administered measure of literacy, spoke either English or Spanish, were not receiving special education services, and had not been previously retained in first grade. Details on recruitment of the 784 participants are reported in Hughes & Kwok (2006). No evidence of selective consent was found. Of these 784 participants, 695 (88.6%) (ethnic composition 23% African American, 38% Hispanic, and 34% Caucasian) met the following criteria for participation in the current study: 1) were still active in the study at Year 5, and 2) had data for at least one of the major variables from Year 2 to Year 5. These 695 students did not differ from the 89 students who did not meet inclusion criteria on any demographic variables or study variables at baseline (Year 1). At entrance to first grade, children’s mean age was 6.57 (SD = 0.38) years. Children’s mean Broad Reading and Broad Math Woodcock Johnson III (Woodcock, McNew, & Mather, 2001) achievement standard scores at baseline were 96.4 (SD =17.76) and 100.84 (SD = 14.08), respectively. On the basis of family income, 61 % of participants were eligible for free or reduced lunch. In Year 2, these 687 children were located in 270 classrooms.

Design Overview

Assessments were conducted annually for five years, beginning when participants were in first grade (Year 1). Covariates and baseline measures of study variables were collected in Year 1. Measures of social relatedness (teacher-student relationship and peer relatedness) were assessed in Years 2, 3, and 4. Academic self-efficacy was assessed in Year 5. Teachers reported on the quality of the teacher-student relationship. Classmates reported on children’s academic competencies and their liking for the child, and students reported on perceived academic self-efficacy.

Measures

Peer Relatedness

Peer sociometric procedures were used to assess classmates’ perceptions of children’s academic competencies and social preference (Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985; Realmuto, August, Sieler, & Pessoa-Brandao, 1997). In individual interviews, child participants were asked to name classmates who best fit each of several behavioral descriptors. Although only children with written parent consent provided nominations, all children in the class were eligible to be nominated for each descriptor. Children could name as few or as many classmates as they wanted for each descriptor. A child’s peer nomination score for each item was obtained by summing all nominations received and standardizing the score within the classroom. Because reliable and valid sociometric data can be collected using the unlimited nomination approach when as few as 40% of children in a classroom participate (Terry, 1999, 2000), sociometric scores were computed only for children located in classrooms in which at least 40% of classmates participated in the sociometric assessment. The mean rate of classmate participation in sociometric administrations was .65 (range .40 to .95), and the median number of children in a classroom providing nominations was 12.

Peer academic reputation

Students were asked to nominate classmates for three academic descriptors: Best at school work (“These kids are best at schoolwork. They almost always get good grades and teachers often use their work as examples for the rest of the class”); best at math (“These kids are best in math. They almost always get good grades in math and the teacher calls on them to work hard math problems”); and best at reading (“These kids are best in reading. They usually get good grades in reading, and the teacher calls on them to read aloud or read hard words”). Children as young as first grade are reliable reporters of classmates’ behavioral traits (Hughes, Zhang, & Hill, 2006; Realmuto et al., 1997) and academic performance (Stipek, 1981).

Peer-rated liking

In individual sociometric interviews, children were asked to indicate their liking for each child in the classroom on a 5-point scale. Specifically, the interviewer named each child in the classroom and asked the child to point to one of five faces ranging from sad (1 = don’t like at all) to happy (5 = like very much). A child’s mean liking score was the average rating received by classmates. An extensive literature provides evidence of good validity and short-term stability for liking ratings for elementary grade children (Terry & Coie, 2001).

Social preference

During the sociometric interview, children were also asked to name all the children in their classrooms whom they “liked the most” and whom they “liked the least.” Social preference scores were computed as the standardized liked most nomination score minus the standardized liked least scores (Asher & Dodge, 1986).

Teacher-student relationship quality

The 22-item Teacher Student Relationship Inventory (TSRI; Hughes Gleason & Zhang, 2005) is based on the Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester,1985). Teachers indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale their level of support (16 items) or conflict (6 items) in their relationships with individual students. The scale has demonstrated good predictive and construct validity (Meehan, et al., 2003; Hughes & Kwok, 2007). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis identifies three scales: warmth (13 items), intimacy (3 items), and conflict (6 items). For the current study the warmth and conflict scales were used, as the intimacy scale is less relevant to the construct of teacher provision of support. Example warmth scale items (α = .94) include “I enjoy being with this child”; “This child gives me many opportunities to praise him or her”; and “This child talks to me about things he/she doesn’t want others to know.” Example conflict scale items (α = .91) include “This child and I often argue or get upset with each other” and “I often need to discipline this child.”

Academic Self Efficacy

Perceived cognitive competence

In individual interviews, children completed the sex-appropriate version of the Self Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1985). Only the Scholastic Competence scale was used. To administer the measure, the examiner presents each child with a pair of statements and asks the child to identify which statement is more like the child. Each of the six items on the Scholastic Competence Scale of the Self Perception Profile for Children consists of two opposite descriptions, e.g. “Some children do very well in their classwork” but “Other children don’t do very well in their classwork”. Children choose the description that is more like them and then indicate whether the description is somewhat true or very true for them. Accordingly, each item is scored on a four-point scale with a higher score reflecting a more positive self view. The internal consistency for these six items for our sample was .63.

Reading and math competency beliefs

Children’s perceived reading and math competencies were assessed with the Competence Beliefs and Subjective Task Values Questionnaire (Eccles, Wigfield, Harold, & Blumenfield, 1993). The math and reading scale consist of 5 items each. Specifically children were asked how good they were at in that domain, how good they were relative to the other things they do, how good they were relative to other children, how well they expected to do in the future in that domain, and how good they thought they would be at learning something new in that domain. We followed Eccles et al.’s recommendation to provide graphic representation of the response scale for younger children. Specifically, children were asked to respond by pointing on a thermometer numbered 0 to 30. The end point and midpoint of each scale were also labeled with a verbal descriptor of the meaning of that scale point (e.g., the number 1 was labeled with the words “not at all good,” or “one of the worst) the number 15 was labeled with the words “ok,” and the number 30 would be labeled with the words “very good” or “one of the best”). The internal consistency for the Reading and Math scales were .86 and .87, respectively, for our sample.

Child IQ, Familial Economic Background, and Year 1 Academic Self Efficacy

Information about children’s IQ, familial economic adversity, and Year 1 academic self efficacy beliefs were collected as factors that might be associated with the other variables in the study. Each measure is described below.

Cognitive ability (IQ)

Children were individually tested at school at 1st grade with the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT; Bracken & McCallum, 1998). The UNIT is a nationally standardized non-verbal measurement of the general intelligence and cognitive abilities of children and adolescents. We used the Abbreviated version of the UNIT that yields a full scale IQ which is highly correlated with scores obtained with the full battery (r=.91) and has demonstrated good test-retest and internal consistency reliabilities as well as construct validity (Hooper, 2003; Bracken & McCallum, 1998).

Economic adversity

Children’s eligibility for free or reduced lunch at 1st grade was used as an indicator of children’s economic adversity (coded as a dichotomous variable with 0 = no adversity and 1 = adversity). Information on eligibility was provided by school records and based on children’s family income.

Baseline cognitive competence

The Scholastic Competence Scale of the Pictorial scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children (Harter & Pike, 1981, 1984) assessed baseline levels of academic self-efficacy (alpha = .78).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were conducted and the means and standard deviations for the observed variables in the hypothesized models are presented in Table 1. The variables were screened for normality and outliers. All variables were within the normal range according to the cutoff values of 2 for skewness and 7 for kurtosis (West, Finch, & Curran, 1995).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Major Analysis Variables

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Liking2 | −0.12 | 1.03 |

| Liking3 | −0.15 | 0.98 |

| Liking4 | −0.05 | 0.95 |

| Prefer2 | −0.11 | 0.98 |

| Prefer3 | −0.15 | 0.98 |

| Prefer4 | −0.04 | 0.95 |

| P-Work2 | −0.16 | 0.86 |

| P-Work3 | −0.27 | 0.77 |

| P-Work4 | −0.17 | 0.79 |

| P-Math2 | −0.18 | 0.88 |

| P-Math3 | −0.23 | 0.81 |

| P-Math4 | −0.15 | 0.82 |

| P-Read2 | −0.15 | 0.92 |

| P-Read3 | −0.23 | 0.79 |

| P-Read4 | −0.18 | 0.81 |

| T-Warm2 | 3.93 | 0.85 |

| T-Warm3 | 3.94 | 0.85 |

| T-Warm4 | 3.90 | 0.88 |

| T-Con2 | 4.16 | 1.00 |

| T-Con3 | 4.21 | 0.95 |

| T-Con4 | 4.26 | 0.91 |

| CogCmp5 | 2.76 | 0.71 |

| MathCmp5 | 22.25 | 5.85 |

| ReadCmp5 | 21.33 | xs5.55 |

Note. N = 695. Variable naming convention:

1. The numbers in the row headings refer to the timing of assessment.

2. T- = Teacher-rated; P- = Peer-nominated; Cog = Cognitive; Cmp = Competence; Liking = Mean Student Rating; Prefer = Preference Score; Warm = Warmth; Con = Conflict.

Measurement Model and Correlations between Latent Factors

The hypothesized structural model was examined by using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square statistic test (MLR; v.5.2, Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2007). To address the missingness, we analyzed all the models using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method under Mplus, which applies the expectation maximization algorithm described in Little and Rubin (1987). To account for the dependence among the observations (students) within clusters (classrooms) at year 2, analyses were conducted using the “complex analysis” feature in Mplus (v.5.2, Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2007); this accounts for the nested structure of the data by adjusting the standard errors of the estimated coefficients.

The measurement model for the nine latent factors in the three-wave longitudinal model had an adequate fit, χ2 (153) = 258.710 , p < .001, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.032, SRMR = 0.033. The factor loadings were adequate, ranging from .63 to .98 (Comrey & Lee, 1992; Crocker & Algina, 1986). Table 2 reports the factor loadings for each of the latent variables. All the model estimated loadings were significant in a positive direction. The correlation matrix between the nine latent factors in the hypothesized model is presented in Table 3. The bivariate correlations between latent factors were consistent with previous literature and with the hypothesized pathways. Peer liking, PAR, and teacher-student relationship quality were all positively correlated within and across years two, three and four.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings of the Latent Variables

| Unstandardized Estimate |

Standardized Estimate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PLike2 | Liking2 | 1.00 | .93 |

| Prefer2 | 0.93 | .90 | |

| PLike3 | Liking3 | 1.00 | .93 |

| Prefer3 | 0.97 | .91 | |

| PLike4 | Liking4 | 1.00 | .98 |

| Prefer4 | 0.89 | .89 | |

| PAR2 | P-Work2 | 1.00 | .86 |

| P-Math3 | 1.07 | .89 | |

| P-Read4 | 1.03 | .83 | |

| PAR3 | P-Work2 | 1.00 | .90 |

| P-Math3 | 1.00 | .86 | |

| P-Read4 | 0.91 | .80 | |

| PAR4 | P-Work2 | 1.00 | .91 |

| P-Math3 | 0.97 | .86 | |

| P-Read4 | 0.94 | .83 | |

| TSRQ2 | T-Warm2 | 1.00 | .72 |

| T-Con2 | 1.49 | .91 | |

| TSRQ3 | T-Warm3 | 1.00 | .65 |

| T-Con3 | 1.46 | .87 | |

| TSRQ4 | T-Warm4 | 1.00 | .63 |

| T-Con4 | 1.55 | .94 | |

| ASE5 | CogCmp5 | 1.00 | .75 |

| MathCmp5 | 6.85 | .62 | |

| ReadCmp5 | 4.48 | .43 |

Note. N = 695. Variable naming convention

1. The numbers in the row headings refer to the timing of assessment.

2. Plike = Peer Liking; PAR = Peer Academic Reputation; TSRQ = Teacher Student Relationship Quality; ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy.T- = Teacher-rated; P- = Peer-nominated; Cog = Cognitive; Cmp = Competence; Liking = Mean Student Rating; Prefer = Preference Score; Warm = Warmth; Con = Conflict.

Table 3.

Correlations for Latent Variables in 3-Wave Longitudinal Model and Mediational Model.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Plike2 | - | .52 | .42 | .54 | .40 | .31 | .41 | .34 | .40 | .15 |

| 2. | Plike3 | - | .45 | .33 | .43 | .23 | .37 | .40 | .39 | .06 | |

| 3. | Plike4 | - | .23 | .30 | .43 | .33 | .34 | .35 | .10 | ||

| 4. | PAR2 | - | .65 | .45 | .34 | .28 | .23 | .22 | |||

| 5. | PAR3 | - | .54 | .24 | .31 | .26 | .28 | ||||

| 6. | PAR4 | - | .29 | .32 | .32 | .29 | |||||

| 7. | TSRQ2 | - | .69 | .65 | .03 | ||||||

| 8. | TSRQ3 | - | .75 | .11 | |||||||

| 9. | TSRQ4 | - | .05 | ||||||||

| 10 | ASE5 | - | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Sex | -.04 | -.09 | -.04 | -.10 | -.07 | -.12 | -.22 | -.31 | -.28 | .07 | |

| Economic Adversity |

-.04 | -.02 | -.02 | -.03 | -.05 | -.05 | -.07 | -.08 | -.10 | -.10 | |

| IQ | .14 | .11 | .13 | .12 | .14 | .10 | .15 | .19 | .16 | .14 | |

Note. The numbers in the row headings refer to the timing of assessment. Non-italicized correlations are significant at p < .05 (two-tailed). Plike = Peer Liking; PAR = Peer Academic Reputation; TSRQ = Teacher Student Relationship Quality; ASE = Academic Self-Efficacy.

The zero order correlations between the demographic variables and the nine latent factors are also reported in Table 3. Overall, the pattern of correlations indicated being a girl, higher economic status, and higher IQ were associated with higher peer liking, higher PAR, and better teacher-student relationship quality. Thus, these variables were included as covariates in subsequent SEM analyses that were conducted to test study hypotheses.

As suggested by Cole and Maxwell (2003), we also examined the equilibrium assumption and the factorial invariance across waves of the measurement model using chi-square difference tests for nested models. The equilibrium assumption held, Δχ 2 (12) = 8.87 , p = .71, indicating that the variance and covariances of the latent variables were constant across waves. In addition, the factorial invariance of the factor loadings held, Δχ 2 (6) = 7.73 , p = .26, indicating the relation of the latent variable to the indicators was constant over time. That is, the fit of the measurement model is invariant across time.

SEM Models

We first tested the hypothesized three-wave longitudinal model (see Figure 1). In Figure 1, TSRQ at earlier waves predicts peer liking and PAR the following year with controls for the prior level of peer liking and PAR. The model also includes reciprocal paths from prior peer liking and PAR to later TSRQ. Sex, economic status, and IQ were included as covariates and controlled for each latent variable.

The hypothesized SEM model had a good fit,χ2 (216) = 445.785 , p < .001, CFI = 0.966, RMSEA = 0.039, SRMR = .053. The residual variances of Peer Liking and PAR were correlated at Waves 3 and 4 due to coming from the same source and the modification indices’ suggestion. The revised model had a better fit,χ2 (214) = 364.069 , p < .001, CFI = 0.978, RMSEA = .032, SRMR = .038.

Next, we conducted a series of chi-square difference tests to investigate stationarity of the effects in the hypothesized model. The effects of prior peer liking on later peer liking, prior PAR on later PAR, prior peer liking on later TSRQ, prior TSRQ on later peer liking, and prior PAR on later TSRQ exhibited stationarity across Years 2 and 3 as well as Year 3 and 4. The effect of prior TSRQ on later TSRQ was not stationary, Δχ2 (1) = 4.58 , p = .03; the autoregressive path of TSR was stronger from year 3 to 4 (β = .75, p < .001) than from year 2 to 3 (β = .65, p < .001). Nor was the effect of prior TSRQ on later PAR stationary, Δχ2 (1) = 6.87 , p = .009; the path from TSRQ to PAR was stronger from year 3 to 4 (β = .19, p < .001) than from year 2 to 3 (β = .06, p = .16).

After taking stationarity into consideration, we obtained a simpler model (i.e., a model with more degrees of freedom because the stationary paths were constrained to be the same across time) that fitted the data equally well, with χ2 (219) = 366.128 , p < 0.001; CFI = 0.978; RMSEA = .031; SRMR = .039. The model with parameter estimates is shown in Figure 1. TSRQ at Waves 2 and 3 both had significant impacts on Peer Liking in the subsequent waves; only TSRQ at Wave 3 had a significant impact on PAR at Wave 4. Peer Liking at Waves 2 and 3 had a significant impact on TSRQ at subsequent waves, but none of the PAR had significant impacts on TSRQ.

We were also interested in testing the indirect, or mediated, effect of Year 3 TSRQ on Year 5 Academic Self-Efficacy via peer relatedness variables. Table 3 shows the zero-order correlations of the latent variables with Year 5 academic Self-Efficacy. As expected, Year 4 PAR but not Year 4 Peer Liking was significantly correlated with Year 5 Academic Self-Efficacy. We then tested the hypothesized meditational model (See Figure 2). In Figure 2, Year 3 TSRQ was hypothesized to affect Year 5 Academic Self-Efficacy via its effect on Year 4 PAR. All the endogenous variables were controlled for the corresponding Year 2 baseline scores. TSRQ at Year 3 was positively correlated with PAR at Year 4, PAR at Year 4 was positively correlated with Academic Self-Efficacy at Year 5; unexpectedly, TSRQ at Year 3 was not significantly correlated with Academic Self-Efficacy at Year 5. In this regard, several studies (MacKinnon et al., 2000; MacKinnon et al., 2002; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) indicate that a direct effect of a predictor on the outcome is not necessary to test for an indirect effect because this test may not be significant under certain circumstances, such as the examination of distal mediation effects. A comparison of different common methods for testing for indirect, or mediated, effects found that keeping this restricted step results in the lowest power to detect real effects (MacKinnon et al., 2002). These authors found that the best balance of Type 1 error and statistical power across all cases is the joint significance of the two effects comprising the intervening variable effect. Therefore, we continued with the hypothesized model and tested the joint significance of the effect of TSRQ at Year 3 on PAR at Year 4 and the effect of PAR at Year 4 on Academic Self-Efficacy at Year 5.

The hypothesized model was tested, and the fit was good, χ2 (47) = 69.850 , CFI = .990, RMSEA = .027, SRMR = .029. As shown in Figure 2, the path from Year 3 TSRQ to Year 4 PAR and the path from Year 4 PAR to Year 5 Academic Self-Efficacy were significant (βs = .23 and .25 respectively, ps <.001).

Following Kenny, Kashy, and Bolger (1998), the indirect effect for the PAR pathway to achievement was tested by multiplying the non-standardized path coefficients corresponding to the indirect effects. Sobel’s (1982) test of mediation effects (i.e., ) along with the delta method standard error (i.e., ) was used (Krull & MacKinnon, 1999, 2001). The indirect effect from Year 3 TSRQ to Year 4 PAR and then to Year 5 Academic Self-Efficacy was significant (β = .06, p = .003).

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the reciprocal effects between two domains of classroom relationships: teacher student relationship quality (TSRQ) and peer relatedness. Consistent with study hypotheses, peer liking and TSRQ exhibit bidirectional effects across the three years. Furthermore, these effects are equivalent across the two time intervals. Although previous research has found an effect of TSRQ on peer liking, this is the first study to document reciprocal effects of peer liking on TSRQ. Perhaps positive affective relationships in each domain contribute to children’s interest in, liking for, and participation in school, which contribute to more positive teacher and peer relationships. Results for reciprocal effects between TSRQ and peer academic reputation (PAR) were only partially consistent with study hypotheses. Unexpectedly, PAR did not have an effect on TSRQ across either time period, above continuity in TSRQ and the effect of peer liking. Perhaps the quality of students’ affective relationships with teachers is influenced more by child social and behavioral characteristics, such as agreeableness and prosocial behavior, than by children’s academic reputations. However, TSRQ had an effect on PAR from Year 3 to Year 4 but not from Year 2 to Year 3. Thus, as expected, the effect of TSRQ on PAR may increase with age. As students transition from primary grade to upper elementary or middle school grades, social comparison cues are more prevalent (Urdan & Midgley, 2003), and students may be more cognitively capable of using social comparison cues to make inferences about students’ characteristics (Kuklinski & Weinstein, 2001). Thus students’ observations of teacher-student interactions may serve as an affective bias that shapes their perceptions of students’ academic abilities.

We were also interested in testing a theoretical model positing that peer relatedness variables mediate the effect of TSRQ on academic self efficacy. Academic self efficacy was selected as the outcome based on its well documented influence on subsequent academic engagement and achievement The bivariate correlations revealed significant correlations between Year 4 PAR (but not Year 4 Peer liking) and Year 5 Academic Self efficacy. Thus only Year 4 PAR was included in the meditational analysis. As expected, Year 4 PAR mediated the effect of Year 3 TSRQ on Year 5 Academic Self Efficacy.

Peer liking and PAR were moderately correlated with each other at each time period (rs range from .43 to .54). Furthermore, they each evince small to moderate correlations with TSRQ (rs with TSRQ range from .31 to .34 for PAR and from .35 to .41 for Peer liking). Yet the two dimensions differ in their influence on different outcomes. Only Peer Liking exerts a unique effect on TSRQ, and only PAR predicts Academic Self Efficacy. These findings support the view that peer relationships are multi-faceted and that different dimensions influence adjustment in different ways.

Limitations and future directions

The measure of TSRQ was based only on teacher report. However, several factors minimize the probability that results are due to rater bias. Different teachers reported on the TSRQ each year, TSRQ was moderately stable across years, and the pattern of associations between TSRQ and other study variables was generally consistent across years. Teacher reports of the teacher-student relationship, however, are limited in that they do not identify specific teacher practices that account for its effects. Observations of teacher practices are necessary to identify these practices. The inclusion of student report of TSRQ would also increase our understanding of the effect of the teacher-student relationship on students’ peer relationships and perceived cognitive competence. Although student’s reports of TSRQ show only modest relationships with teachers’ reports of TSRQ (Henricsson & Rydell, 2004; Hughes et al., 1999; Mantzicopoulos and Neuharth-Pritchett, 2003; Murray et al., 2008), they may have implications for students’ self-views and classroom engagement.

The current sample is an academically at-risk sample. Students at risk for school failure due to adverse family backgrounds or low readiness skills may be more responsive to variations in levels of teacher support and peer relationships (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Meehan et al., 2003; Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002). Thus one can not generalize these findings to higher achieving samples.

Implications for practice and policy

Extensive research documents the importance of students’ relationships with their teachers to their academic and behavioral trajectories. The current findings suggest that an underexplored mechanism accounting for this effect is the influence of the teacher student relationship on a student’s peer academic reputation. Peers may use observations of teacher-student interactions to draw inferences about students’ abilities. A positive peer reputation for achievement may be an especially important asset for low income, minority children and/or children at risk for academic failure.

Study findings are consistent with the metaphor of the teacher as an “invisible hand” in the classroom. Through their instructional and social-emotional practices, teachers establish the context in which learning takes place, peers relate to each other, and students develop views of self as capable or not, and as cared for or not. Stated somewhat differently, the teacher is the primary architect of the classroom context, a context that surrounds and regulates interactions within it (Pianta & Walsh, 1996). Large scale national studies have consistently identified instructional and social-emotional dimensions of classroom climate as distinct factors (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; NICHD ECCRN, 2002) that contribute differentially to child outcomes. Classroom instructional practices such as grouping children for instruction based on ability, rewarding correct answers versus effort and improvements, and responding differently to students for whom the teacher holds high or low expectations for achievement may make relative ability differences in the classroom more or less salient to students and communicate which student characteristics are most highly valued. These practices not only have implications for students’ motivation and engagement but also for their peer reputation on a number of social and academic dimensions (Urdan & Schoenfelder, 2006; Wigfield, Eccles, Schiefele, Roeser, & Davis-Kean, 2006). Teacher practices also establish the social-emotional climate of the classroom, creating norms and shared expectations for how students relate to each other (Battistich & Horn, 1997; Wentzel, 1999).

Much more is known about teacher practices that promote student positive growth and development than is known about strategies for increasing teacher use of these practices. Developing and testing teacher-focused interventions aimed at creating and sustaining affectively positive, encouraging relationships with students represents a critical need. Interventions that aim to enhance the social-emotional climate of the classroom and teacher-student relationships have shown promise (e.g., Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999; McIntosh, Rizza, & Bliss, 2000; Raver et al., 2008) One obstacle to the success of these intervention may be teachers’ beliefs about their role in developing relationships with students. In a study of middle school homeroom teachers (Davis, 2006), over one-third of teachers were uncertain as to whether developing relationships with students was their responsibility, and a sizeable number of teachers expressed the belief that they were not obligated to meet students’ relational needs, or that doing so would not improve or might hamper students’ academic motivation and achievement. Increasing teachers’ awareness of the myriad ways in which they influence classroom social relationships and students’ motivation should be a focus of both pre-service and in-service teacher professional development programs. Teacher professional development programs that provide didactic instruction and modeling in creating a positive social-emotional context combined with classroom-based feedback and support in applying the taught concepts result in greater improvements in positive climate and teacher sensitivity than interventions that only provide didactic instruction and modeling (Raver et al., 2008). Additional research supports the view that “in the moment” feedback and support are critical to sustained changes in teacher practices (Landry, Anthonly, Swank, & Monseque-Bailey, 2009). Professional development interventions that target the classroom social-emotional context and that incorporate best practices in teacher professional development hold promise for improving the educational attainment of all students.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant to Jan N. Hughes from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 R01 HD39367).

Contributor Information

Jan N. Hughes, Department of Educational Psychology Texas A&M University

Qi Chen, Department of Educational Psychology University of North Texas.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Horsey CS. From first grade forward: Early foundations of high school dropout. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Altermatt ER, Pomerantz EM. The development of competence-related and motivational beliefs: An investigation of similarity and influence among friends. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ames C. Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1992;84:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Dodge KA. Identifying children who are rejected by their peers. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:444–449. [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA. Contributions of teacher-child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington BL, Hendricks B. Differentiating characteristics of high school graduates, dropouts, and nongraduates. Journal of Educational Research. 1989;82:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V, Horn A. The relationship between students’ sense of their school as a community and their involvement in problem behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1997–2001. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL. Understanding and treating peer rejection. Guilford Press; NY, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken BA, McCallum S. Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test. Riverside; Chicago: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 6th ed 1. Theoretical models of human development. Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Markman LB. The contribution of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. The Future of Children. 2005;15:139–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;54:1386–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES. Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43(5):407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES, Ladd GW, Herald SL. Peer exclusion and victimization: Processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection and children’s classroom engagement and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Pianta R, Howes C. Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:415–436. [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradovic J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79:359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B. A competency-based model of child depression: A longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro WA, Eder D. Children’s peer cultures. Annual Review of Sociology. 1990;16:197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, White K. Structure of peer impressions of children’s competence: Validation of the peer nomination of multiple competencies. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Change in self-perceived competence as a function of peer and teacher evaluation. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:682–688. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE, Martin JM. Reflected self-appraisals: Strength and structure of the relation of teacher, peer, and parent ratings to children’s self-perceived competencies. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A First Course in Factor Analysis. 2 ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Initial impact of the fast track prevention trial for conduct problems: II Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999b;67:648–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar M, Sroufe LA, editors. Minnesota symposium on child psychology. Vol. 22. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Kawabata Y. Relational aggression and gender: An overview. In: Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Waldman ID, editors. The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. Cambridge University Press; New York City: 2007. pp. 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker LM, Algina J. Introduction to classical and modern test theory. CBS College Publishing; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Davis HA. Exploring the contexts of relationship quality between middle school students and teachers. The Elementary School Journal. 2006;106:193–223. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl DS, Lemerise EA, Caverly SL, Ramsay S, Roberts J. Peer relations and school adjustment in ungraded primary children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90(3):506–506. [Google Scholar]

- Doumen S, Verschueren K, Buyse E, Germeijs V, Luyckx K, Soenens B. Reciprocal relations between teacher-child conflict and aggressive behavior in kindergarten: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:588–588. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Wigfield A, Harold RD, Blumenfeld P. Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development. 1993;64:830–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders N, Havumaki S. The effect of teacher-pupil contacts involving praise on the sociometric choices of students. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1960;51(2):65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Flook L, Repetti R, Ullman JB. Classroom social experiences as predictors of academic performance. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:319–327. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, Skinner E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Domitrovich CE, Welsh JA. Peer academic reputation in elementary school: Associations with changes in self-concept and academic skills. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Rulison KL, Davidson AJ, Welsh JA. A reputation for success (or failure): The association of peer academic reputations with academic self-concept, effort, and performance across the upper elementary grades. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:625–636. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools. 1993;30:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gruman DH, Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Fleming CB. Longitudinal effects of student mobility on three dimensions of elementary school engagement. Child Development. 2008;79:1833–1852. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development. 2005;76:949–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg MS, Rollins KB. The first two years of school: Teacher-child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Harris DN, Herrington CD. Accountability, standards, and the growing achievement gap: Lessons from the past half-century. American Journal of Education. 2006;112:209–238. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The self-perception profile for children: A revision of the perceived competence scale for children. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The development of self-representations. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. 5th ed 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1998. pp. 553–617. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Pike R. The pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaven PCL. The social psychology of adolescence. Palgrave Macmillan; New York City: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heider I. The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley; New York, NY: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Henington C, Hughes JN, Cavell TC, Thompson B. The role of relational aggression in identifying aggressive boys and girls. Journal of School Psychology. 1998;36:457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Kwok O. Classroom engagement mediates the effect of teacher-student support on elementary students’ peer acceptance: A prospective analysis. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;43:465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Kwok O. Classroom engagement mediates the effect of teacher-student support on elementary students’ peer acceptance: A prospective analysis. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;43:465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Kwok O. The influence of student-teacher and parent-teacher relationships on lower achieving readers’ engagement and achievement in the primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;99:39–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Zhang D. Effects of the Structure of Classmates’ Perceptions of Peers’ Academic Abilities on Children’s Academic Self-Concept, Peer Acceptance, and Classroom Engagement. Journal of Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2007;32:400–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Jackson T. Influence of teacher-student relationships on aggressive children’s development: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:173–184. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Willson V. Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher-student relationship. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Dyer N, Luo W, Kwok O. Effects of peer academic reputation on achievement in academically at-risk elementary students. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:182–194. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Luo W, Kwok O, Loyd L. Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A three year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:1–14. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Zhang D, Hill CR. Peer Assessments of Normative and Individual Teacher-Student Support Predict Social Acceptance and Engagement Among Low-Achieving Children. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;43:447–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S. Interpretations of peer behavior: Affective bias in childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 1986;57:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th Ed McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann TA. Natural peer groups as contexts for individual development: The case of children’s motivation in school. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:970–977. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklinski MR, Weinstein RS. Classroom and developmental differences in a path model of teacher expectancy effects. Child Development. 2001;72:1554–1578. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Peer relationships and social competence during early and middle childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children’s school adjustment? Child Development. 1997;68(6):1181–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Anthony JL, Swank PR, Monseque-Bailey P. Effectiveness of comprehensive professional development for teachers of at-risk preschoolers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101:448–465. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner R. Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. 5th ed Wiley & Sons; New York: 1998. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Changing organism-context relations as a basic process of development: A developmental contextual perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–317. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediated and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW. Age and sex effects in multiple dimensions of self-concept: Preadolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1989;81:417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Morison P, Pellegrini DS. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:523–533. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DE, Rizza MG, Bliss L. Implementing empirically supported interventions: Teacher-child interaction therapy. Psychology in the School. 2000;37:453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH. Mind, self, and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan BT, Hughes JN, Cavell TA. Teacher-Student Relationships as Compensatory Resources for Aggressive Children. Child Development. 2003;74:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SH, DeRosier ME. Teacher preference, peer rejection, and student aggression: A prospective study of transactional influence and independent contributions to emotional adjustment and grades. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:661–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Change in teacher efficacy and student self- and task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1989;81:247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5 ed Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Development Early Child Care Research Network The relation of global first grade classroom environment to structural classroom features, teacher, and student behaviors. Elementary School Journal. 2002;102:367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G, Losen D, Wald J, Swanson CB. Losing our future: How minority youth are being left behind by the graduation rate crisis. The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University; Cambridge, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Belsky J, Houts R, Morrison F, National Institute of Child Health. Human Development (NICHD) Early Child Care Research Network, Rockville, MD, US Opportunities to learn in america’s elementary classrooms. Science. 2007;315:1795–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1139719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh MJV, Hart D. Identity development and peer group participation. In: McLellan JA, Pugh MJV, editors. The role of peer groups in adolescent social identity: Exploring the importance of stability and change. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1999. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Metzger M, Champion KM, Sardin L. Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary findings from a randomized trial implemented in head start settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008;23:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Realmuto GM, August GJ, Sieler JD, Pessoa-Brandao L. Peer assessment of social reputation in community samples of disruptive and nondisruptive children: Utility of the revised class play method. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:67–76. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retish PM. Changing the status of poorly esteemed students through teacher reinforcement. Journal of Applied and Behavioral Science. 1973;9:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ, Bezruczko N. School adjustment of children at risk through fourth grade. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1993;39:457–480. [Google Scholar]

- Risi S, Gerhardstein R, Kistner J. Children’s classroom peer relationships and subsequent educational outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:351–361. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Freedman-Doan C. Academic functioning and mental health in adolescence: Patterns, progressions, and routes from childhood. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:135–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Stiller JD, Lynch JH. Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and friends as predictors of academic motivation and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:226–249. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Davis L, Williams T, Williams JH. Gender differences in self-perceptions and academic outcomes: A study of African American high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Measelle JR, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior: Contributions of child characteristics, family characteristics, and the teacher-child relationship during the school transition. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Connell JP. Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1998;63(Nos. 2-3) Serial No. 254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E, Belmont M. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek DJ. Children’s perceptions of their own and their classmates’ ability. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1981;73:404–410. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. Predictors of peer rejection in early elementary grades: Roles of problem behavior, academic achievement, and teacher preference. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1989;18:360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AR, Trickett PK. Teacher preference and children’s sociometric status in the classroom. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1989;35:343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R, Coie JD. A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:867–880. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Measurement and scaling issues in sociometry: A latent trait approach. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Recent advances in measurement theory and the use of sociometric techniques. In: Cillessen AHN, Bukowski WM, editors. Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system: New directions for child and adolescent development. No. 88. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2000. pp. 27–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Future of Children . The Future of Children. Vol. 15. The Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and the Brookings Institute; [Retrieved February 15, 2005]. 2005. School Readiness: Closing Racial and Ethnic Gaps. www.futureofchildren.org. [Google Scholar]

- Thijs J, Verkuyten M. Peer victimization and academic achievement in a multiethnic sample: The role of perceived academic self-efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:754–754. [Google Scholar]

- Urdan T, Midgley C. Changes in the perceived classroom goal structure and pattern of adaptive learning during early adolescence. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2003;28:524–551. [Google Scholar]

- Urdan T, Schoenfelder E. Classroom effects on student motivation: Goal structures, social relationships, and competence beliefs. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Graham S, Stern P, Lawson E. Using affective cues to infer causal thoughts. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein RS, Marshall HH, Sharp L, Botkin M. Pygmalion and the student: Age and classroom differences in children’s awareness of teacher expectations. Child Development. 1987;58:1079–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationship: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:76–97. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- White KJ, Kistner J. The influence of teacher feedback on young children’s peer preferences and perceptions. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:933–940. [Google Scholar]