Abstract

The antigrowth and immunomodulatory actions of interferons (IFNs) have enabled these cytokines to be used therapeutically for the treatment of a variety of hematologic and solid malignancies. IFNs exert their effects by activation of the Jak/Stat signaling pathway. IFNγ stimulates the tyrosine kinases Jak1 and Jak2, resulting in activation of the Stat1 transcription factor, whereas type 1 IFNs (IFNα/β) activate Jak1 and Tyk2, which mediate their effects through Stat1 and Stat2. Disruption in the expression of IFNγ, IFNα receptors, or Stat1 inhibits antitumor responses and blunt cancer immunosurveillance in mice. Mutations in Jak2 or constitutive activation of Jak1 or Jak2 also promote the development of a variety of malignancies. Although there are data indicating that Tyk2 plays a role in the pathogenesis of lymphomas, the effects of Tyk2 expression on tumorigenesis are unknown. We report here that Tyk2−/− mice inoculated with 4T1 breast cancer cells show enhanced tumor growth and metastasis compared to Tyk2+/+ animals. Accelerated growth of 4T1 cells in Tyk2−/− animals does not appear to be due to decreased function of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, or NK cells. Rather, the tumor suppresive effects of Tyk2 are mediated at least in part by myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which appear to be more effective in inhibiting T cell responses in Tyk2−/− mice. Our results provide the first evidence for a role of Tyk2 in suppressing the growth and metastasis of breast cancer.

Introduction

Deregulated activation of the Jak/Stat pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many cancers. The growth of these malignancies is often associated with promiscuous phosphorylation of Stat3 and Stat5. Aberrant phosphorylation of these transcription factors may be mediated by constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinases Jak1 or Jak2. Jak1 activation has been associated with transformation by Src or v-Abl (Danial and others 1995, 1998; Zhang and others 2000), whereas the TEL-JAK2 fusion oncogene and gain-of-function mutations in Jak2 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of leukemias and myeloproliferative disorders (Kralovics and others 2005).

Tyk2 is a member of the Jak family, which primarily mediates the actions of type 1 interferons (IFNα/β) and interleukin (IL)-12. It has also been implicated in signaling by several other cytokines, including IL-10, IL-6, and IL-13. Tyk2−/−mice display a variety of defects in both innate and adaptive immunity consistent with their roles in mediating the actions of IFNα/β and IL-12. In contrast to Jak1 and Jak2, which have been clearly implicated in cell transformation, the role of Tyk2 in cancer is ambiguous and very limited. In DU-145 human prostate cancer cells disruption of the expression of Tyk2 with siRNA inhibited the ability of these cells to migrate in a matrigel invasion assay (Ide and others 2008). In contrast to the expression of Tyk2 facilitating the ability of prostate cancer cells to invade, Tyk2−/− mice are more susceptible to Abelson murine leukemia virus-induced B cell leukemia/lymphoma and TEL-JAK2-induced T cell lymphoid leukemia (Lacronique and others 1997; Carron and others 2000; Stoiber and others 2004). The lack of Tyk2 expression in this tumor model is associated with decreased cytotoxicity of Tyk2−/− NK and NKT cells (Stoiber and others 2004).

Considering that both IFNα/β and IL-12 have antitumor activity, and mediate activation of the Jak/Stat pathway through Tyk2, we initiated a series of experiments in Tyk2−/− mice to examine whether the expression of Tyk2 influences the ability of 4T1 breast cancer cells to grow and metastasize. We chose 4T1 cells for these studies because they were derived from a spontaneous mouse mammary carcinoma and closely resemble the pathology of human breast cancer. 4T1 tumors metastasize to the lung, liver, brain, and bone relatively early during the growth of the primary tumor. This model for breast cancer also has the advantage that the tumors grow and metastasize in immunocompetent BALB/C mice.

Materials and Methods

Cells

The 4T1 mouse mammary carcinoma cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Serum Source International, Inc.), 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech, Inc.).

Mice

BALB/cJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Tyk2−/− mice (Shimoda and others 2000) on a BALB/c background were obtained from Dr. Ana M. Gamero (Temple University). Tyk2−/− mice were genotyped by using the following primers. Forward primer for Tyk2+/+ mice: 5′- TGG ACA AAA TGG AGT GAG TGT AAG-3′; reverse primer for Tyk2+/+ mice: 5′-CTG GGT CAT GGC TGG AAA AGC CCA-3′; primers for Tyk2−/− mice: 5′- GAT CGG CCA TTG AAC AAG ATG-3′; 5′- CGC CAA GTC CTT CAG CAA TAT-3′. Only female mice were used for these studies.

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant human IL-2 (Cat. No. 200-02) was purchased from Peprotech. 6-Thioguanine (Cat. No. A-4882), methylene blue (Cat. No. M-4159), and Hyaluronidase (Cat. No. H3884) were purchased from Sigma. Elastase (Cat. No. 2279), Collagenase Type 4 (Cat. No. 4188), and Collagenase Type 1 (Cat. No. 4196) were purchased from Worthington.

In vivo tumor study

Female mice were used for these studies. Mice were subcutaneously injected in the mammary gland with 7.0×10 3 4T1 cells in 1× PBS. Tumor growth was assessed morphometrically using calipers, and tumor volumes were calculated according to the formula V (mm3)=L (length)×W2 (width)/2 (4). Tumors and spleens from control and tumor-bearing mice were weighed on a microbalance. This research was conducted under a protocol approved by Virginia Commonwealth University, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Metastatic tumor cell clonogenic assay

4T1 tumor cells are 6-thioguanine resistant. Metastatic cells were quantified by removing organs, plating dissociated cells in medium supplemented with 6-thioguanine, and counting the number of 6-thioguanine-resistant colonies. Lungs and livers were harvested from each experimental group. Liver samples were finely minced and digested in 5 mL of enzyme cocktail containing 1× PBS, 0.01% BSA, 1 mg/mL hyaluronidase, and 1 mg/mL type I collagenase for 20 min at 37°C. Lung samples were minced and digested in enzyme cocktail containing 1× PBS, 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV at 6 units/mL for 75 min at 4°C. After incubation, samples were filtered through 70-μm nylon cell-strainers and washed 2 or 3 times with 1× PBS. Cells were plated with a series of dilutions on 10-cm tissue-culture dishes in DMEM containing 60 μM 6-thioguanine. At this concentration of 6-thioguanine there were no viable cells from liver or lung isolated from mice not innoculated with 4T1 cells (data not shown). Tumor cells formed foci after 10 to14 days, at which time they were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.03% methylene blue. Clonogenic metastases were calculated on a per-organ basis.

IFNγ production

Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− female mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells in the mammary gland. After 5 days of tumor growth, spleens were harvested. Splenocytes (5×106) were then cocultured in the presence of IL-2 (30 U/well) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in the presence or absence of irradiated 4T1 cells (4×105) (15,000 rads). After 24 h of incubation, the supernatants were collected. IFNγ concentration in these supernatants was determined using a mouse IFNγ ELISA set (BD Biosciences) according to manufacture's protocol. IFNγ and other cytokines were also assayed in supernatants from primary 4T1 cell tumors grown in Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− mice. Tumors were collected 34 days after inoculation, and equal weights of tumor were minced and incubated in RPMI 1640 with penicillin/streptomycin for 24 h. Supernatants were analyzed using the mouse inflammation cytometric bead assay kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacture's instructions.

In vivo depletion of lymphoid cells

In vivo NK cell depletion was performed using purified monoclonal antibodies to anti-asialo-GM1 (Cat # 986-1001Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Recipient mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 200 μg of rabbit anti-asialo GM1 or control rabbit Ig serum (SLR66; Equitech-Bio, Inc.) before tumor inoculation. Antibody injections were performed on days 0, 1, 7, 11, 14, and 20, where day 1 is the day of tumor challenge. NK-cell depletion was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes. The presence of NK cells was examined on the following day after each antibody injection by flow analysis staining with anti-mouse FITC-Pan-NK (DX5) (Biolegend) and anti-mouse PE-CD3e (Biolegend) on a FACS Canto™ II flow cytometer.

In vivo T-cell depletion was performed using purified monoclonal antibodies of anti-CD4 (GK1.5) or anti-CD8 (2.43). Mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by i.p. injection of 200 μg Ab. Antibodies were injected on days 1, 6, and 13. Mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells on day 2. The presence of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells was examined on the day following injection by flow cytometric analysis using anti-CD4-FITC (Clone RM4-5), anti-CD3e-PE (Clone 145-2C11), and anti-CD8-FITC (Clone 53-6.7). Control mice were inoculated with 200 μg of purified normal mouse IgG (SLM66; Equitech-Bio, Inc.).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell numbers in tumor-bearing mice

Viable cells were counted and splenocytes (1×106) were stained for 30 min with anti-mouse CD11b (PE-conjugated) and anti-mouse Gr-1 (PE/Cy5-conjugated) (Biolegend). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in spleens were analyzed in a BD FACS Canto™ II flow cytometer.

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester labeling

Splenocytes were resuspended in 5 μM of carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen Cat. No. C34554) in HBSS medium and incubated at room temperature for 5 min, after which 1 mL of heat inactivated FBS was added. Cells were centrifuged at 1,400 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and washed 3 times with HBSS containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS.

In vitro MDSC suppression of T cell proliferation

Ninety-six-well plates were coated with 200 μl of 10 μg/mL anti-CD3e (BD Pharmingen) and incubated for 24 h at 4°C. Unbound antibody was removed by washing 3 times with PBS. Splenocytes (107 cells/mL in complete media) isolated from naïve Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice were used as responder cells. Splenocytes from tumor-bearing Tyk2+/+ and tumor-bearing Tyk2−/− mice were stained with anti-CD11b and anti-Gr1 serum and sorted to collect CD11b+Gr1+ cells (MDSCs). Sorted MDSCs were incubated with CFSE-labeled naïve splenocytes in 1:2 ratio added directly to the culture medium in the presence of IL-2. Soluble anti-CD28 antibody (BD Pharmingen) was also added to the culture medium at 1 μg/mL. Splenocytes were plated at 2×105 cells/well and were allowed to proliferate for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were collected and Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/32. Splenocytes were stained with anti-CD3e and anti-CD4 or anti-CD3e and anti-CD8. CD4+ or CD8+ T cell proliferation was monitored by flow cytometry for decreases in CFSE fluorescence.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for tumor volume and metastatic disease. Other differences between 2 groups were analyzed with the Student's t-test. Results of tumor growth in mice are presented as the means±standard errors (SE) of tumor volume in each group. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

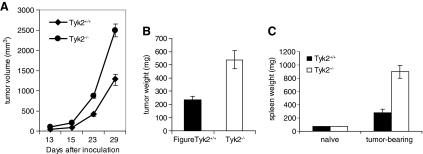

Initial experiments were performed to determine whether Tyk2 played a role in the modulation of tumor growth and metastasis of 4T1 cells. Female mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the mammary gland with 4T1 cells. Tumor volume at the site of injection was measured using calipers every 7 days (Fig. 1A). Mice were sacrificed on day 29 postinoculation and weights of the primary tumor were measured (Fig. 1B). Compared with Tyk2+/+ mice tumor volumes were about 2-fold greater and tumor weights were 3.5-fold greater when tumors were grown in Tyk2−/− animals. Spleen weights from Tyk2−/− mice were also increased about 4-fold compared to Tyk2+/+ mice (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

4T1 cells show enhanced tumor growth in Tyk2−/− mice. Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− female mice (n=12 for each genotype) were inoculated with 4T1 cells in the abdominal mammary gland and tumor growth was monitored. Twenty-nine days after inoculation, mice were sacrificed and primary tumors were collected and weighed (A) Tumor volumes were measured using Vernier calipers. (B) Primary tumor weights. (C) Spleen weights. Each group contained 12 mice. Data bars represent the mean±standard errors. These data are pooled from 2 experiments. Data bars represent the mean±standard errors (P<0.0001). These data are pooled from 2 experiments.

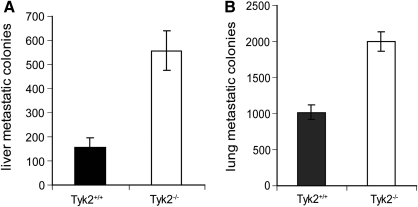

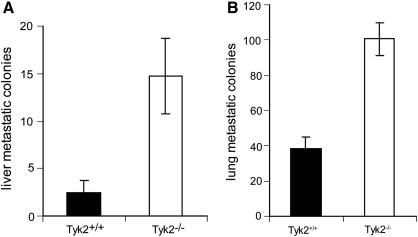

4T1 tumors have the capacity to spontaneously metastasize to a variety of organs, including liver and lung (Ostrand-Rosenberg 2004). Since 4T1 cells are 6-thioguanine resistant, we used clonogenic assays to measured metastatic foci in the liver and lungs of Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice (Fig. 2A, B). The numbers of metastatic colonies in both tissues were significantly elevated in Tyk2−/− compared with Tyk2+/+ tissues. There are 2 possible interpretations of this result. (1) Since primary tumors are larger in Tyk2−/− animals, they may metastasize earlier than tumors in Tyk2+/+ mice, thereby providing a longer time for more metastatic colonies to form. (2) There is an intrinsic deficiency in Tyk2−/− mice that allows the tumors to metastasize with greater efficiency. To distinguish between these possibilities, mice were given intravenous tail vein injections of 4T1 cells, and 10 days later the number of metastatic colonies in the lungs and liver were determined by clonogenic assays (Fig. 3A, B). The numbers of metastatic colonies were significantly greater in both the lungs and livers of Tyk2−/− animals, suggesting that the enhanced size of the primary tumors is not the only mechanism accounting for more metastasis in Tyk2−/− organs. The design of this experiment does not address the possibility that in a Tyk2-null background the ability of cancer cells to invade is also enhanced.

FIG. 2.

Tyk2−/− mice inoculated with 4T1 cells display increased metastatic disease. Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice (n=12) were injected with 4T1 cells in the abdominal mammary gland. Twenty-nine days after inoculation, mice were sacrificed and livers and lungs were collected. Cells isolated from these tissues were plated on 6-thioguanine and colonies were counted after 12–14 days. (A) Numbers of liver metastases. (B) Numbers of lung metastasis. Each group contained 12 mice. These data are pooled from 2 experiments.

FIG. 3.

Tyk2 deficiency promotes metastasis in the absence of a primary tumor. Mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells by tail vein injection. After 10 days, lungs and livers were collected. Metastasis was measured by clonogenic assay. (A) Metastatic colonies in the livers. (B) Metastatic colonies in the lungs. Eight Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice were used for these experiments.

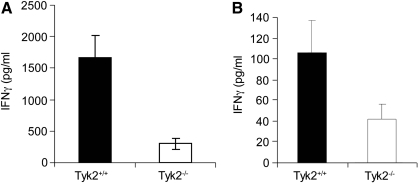

Key components of tumor surveillance are NK cells, CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and the production of IFNγ. Opposing the actions of these players are MDSCs, which promote tumor growth by inhibiting T cell function (Gabrilovich and Nagaraj 2009). We investigated whether defects in these populations contributed to the enhanced growth of 4T1 cells in Tyk2−/− mice. IFNγ production was measured in supernatants collected from irradiated 4T1 cells cocultured with splenocytes from Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4A). IFNγ production was decreased about 5-fold in Tyk2−/− splenocytes from tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5A). These results are consistent with defects in IL-12 induction of IFNγ that has been identified in Tyk2−/− mice (Karaghiosoff and others 2000; Shimoda and others 2000).

FIG. 4.

Tyk2−/− splenocytes sensitized to 4T1 cells produce less interferon-γ (IFNγ) than Tyk2+/+ splenocytes. Mice (n=8) were inoculated with 4T1 cells. After 5 days, spleens were harvested. (A) Splenocytes (5×106) were cocultured with IL-2 in the presence or absence of irradiated 4T1 (4×105 cells) (15,000 rads). After 24 h, the supernatants were collected and IFNγ concentration was determined using an IFNγ ELISA kit. Data bars represent means and standard errors p<0.03. (B) IFNγ production in tumors isolated from mice inoculated with 4T1 cells was measured as described. Tumors were harvested 7 days after introduction of 4T1 cells into Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− mice (p<0.05).

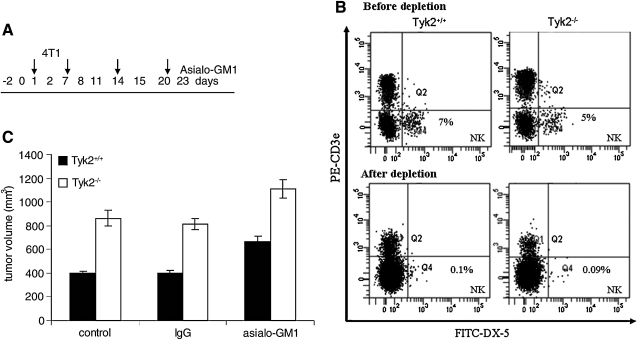

FIG. 5.

Expression of Tyk2 in NK cells does not contribute to 4T1 cell tumor genesis. (A) Protocol for in vivo NK cell depletion. One day before 4T1 cell inoculation Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− mice were injected with 200 μg of anti-asialo GM1 or control serum. Antibody injections were continued on days 7, 14, and 21, where day 2 is the day of tumor challenge. (B) Efficiency of NK cell depletion by flow cytometry is displayed in the FACS scans. (C) NK cells do not contribute to enhanced growth of 4T1 cells in Tyk2−/− mice. Tumor volume (mm3) was measured 23 days after inoculation (top panel). Data bars represent the mean±standard errors. Although there was a slight increase in tumor volumes in both Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice depleted of NK cells, tumors in Tyk2−/− mice remained increased compared to Tyk2+/+ mice in the absence of NK cells.

We also analyzed the production of IFNγ and other cytokines in supernatants of primary 4T1 cell tumors isolated from Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice. The amount of IFNγ produced from tumors derived from Tyk2+/+ mice was about 2.5-fold greater than that produced from tumors derived from Tyk2−/− animals (Fig. 4B). The production of inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, MCP1, and IL-6, was not statistically different in the samples (data not shown).

To determine whether defects in NK cells account for enhanced tumor growth in Tyk2−/− mice, mice were pretreated with antibodies to NK cells 1 day before inoculation with 4T1 cells (day 2). Mice were given additional antibody injections on days 7, 14, and 21 (Fig. 5A). Before depletion, lymphocytes from Tyk2+/+ blood contained about 7% NK cells, whereas Tyk2−/− lymphocytes contained 5% NK cells (Fig. 5B). This difference in NK cell numbers was not statistically significant. Compared with animals injected with IgG control, NK antibody-treated mice contained about 0.1% NK cells (Fig. 5B). Depletion of NK cells caused a modest increase in the rate of tumor growth in both Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that Tyk2-mediated changes in NK cell activity do not contribute to the accelerated rate of tumor growth observed in Tyk2−/− mice.

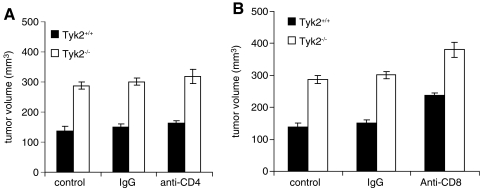

Mice were also injected with either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies to examine whether the loss of activity of these lymphocyte populations contributed to enhanced rates of 4T1 cell growth in Tyk2−/− mice. Blood from Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice contained approximately the same percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (data not shown). Treatment of mice with either antibody depleted CD4 or CD8 cells to 0.1% of the total population (data not shown). Depletion of CD4+ cells had no effect on the rates of tumor growth in either Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− mice. Mice depleted of CD8+ cells showed a slightly increased rate of tumor growth. However, the differences in rates of tumor growth between Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice were maintained in the absence of CD8 cells (Fig. 6A, B).

FIG. 6.

Expression of Tyk2 in CD4+ or CD8+ cells does not contribute to 4T1 cell tumor genesis. (A) CD4+ T cell depletion does not change 4T1 tumor growth. Tumor volume (mm3) was measured 19 days after inoculation with 4T1 cells. Data bars represent the mean±standard errors. CD4+ T cell-depleted group had 8 mice; other groups had 6 mice. P<0.001. (B) CD8+ T cell depletion does not contribute to increased primary tumor growth in Tyk2−/− mice. Tumor volume (mm3) was measured 19 days after inoculation. Although there was a slight increase in tumor volumes in both Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice depleted of CD8+ cells, tumors in Tyk2−/− mice remained increased compared to Tyk2+/+ mice in the absence of CD8+ cells. Data bars represent the mean±standard errors. CD8+ T cell-depleted group had 8 mice; other groups had 6 mice. P<0.0001.

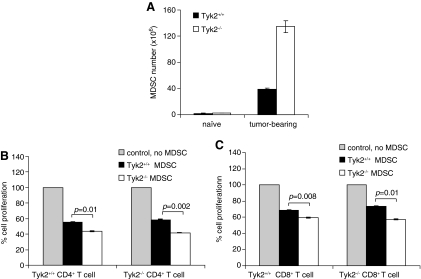

MDSCs are a heterogenous population of cells comprised of myeloid progenitor cells, immature macrophages, immature granulocytes, and immature dendritic cells, all of which suppress T cell function (Gabrilovich and Nagaraj 2009). Numbers of MDSCs increase in spleens of tumor-bearing animals. To determine the possible role of MDSCs in 4T1 cell growth, MDSC levels were measured in the spleens of Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice 21 days after inoculation (Fig. 7). There were approximately 2.5 times as many splenic MDSCs in Tyk2−/− compared to Tyk2+/+ animals. To determine whether there were changes in the ability of MDSCs from Tyk2−/− tumor-bearing mice to suppress T cell proliferation, splenic MDSCs were sorted from Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice. MDSCs were cocultured with Tyk2−/− or Tyk2+/+ naïve splenocytes labeled with CFSE. Proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 7A, B). Compared with MDSCs from Tyk2+/+ spleens, Tyk2−/− spleens have a slight, but significant, increase in suppression of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation. The increased suppressive effects of MDSCs from Tyk2−/− mice were not dependent on whether the T cells used in the assay originated from Tyk2−/− or Tyk2+/+ animals.

FIG. 7.

Tumor-bearing Tyk2−/− mice have higher levels of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) than tumor-bearing Tyk2+/+ animals. (A) Mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells, and 22 days later spleens were harvested and stained for MDSCs. Each group had 3 mice. Data bars represent the mean±standard deviation. Tyk2+/+ and Tyk2−/− mice were inoculated with 4T1 cells. Seventeen days later MDSCs from spleens were collected by sorting for CD11b+Gr1+cells. MDSCs (0.5×106) were incubated with naïve splenocytes (106) labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester. After 48 h incubation, cells were stained with anti-CD3-PE and anti-CD4-PE/Cy5 or anti-CD8a-PE.Cy5. (B) MDSCs are more effective than Tyk2+/+ MDSCs in suppressing T cell proliferation. CD4+ T cell proliferation was measured in cells isolated from Tyk2+/+ or Tyk2−/− mice (C) CD8+ T cell proliferation was measured under the same conditions as CD4+ cells.

Discussion

Although there are many reports indicating that promiscuous activation of Stat3, Stat5, and Jak1 and Jak2 is associated with cell transformation, our understanding of the role of Tyk2 in tumor growth is very limited. Two contradictory studies that address the role of Tyk2 in tumor genesis indicate that its expression enhances the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells, whereas it suppresses c-Abl-induced development of lymphomas and leukemias (Ide and others 2008; Stoiber and others 2004). The role of Tyk2 expression in cancer metastasis until now has been unexplored. We decided to examine the actions of Tyk2 on tumor development because type 1 IFNs and IL-12 mediate their actions through Tyk2, and both of these cytokines are well-known inhibitors of growth of transformed cells, including breast cancer cells. Using the 4T1 model of breast cancer we demonstrate that tumors grow faster and metastasize more rapidly in Tyk2−/− mice than in Tyk2+/+ animals. The increased metastatic potential of tumors in a Tyk2−/− background is not simply due to the increased size of the primary tumors. To determine which hematopoietic cells may be altered by the expression of Tyk2, wild-type and Tyk2−/− mice were depleted of NK, CD4+, or CD8+ T cells. Our results indicate that the antigrowth function of these cells is not altered by the expression of Tyk2. These findings contrast with those of Stoiber and others, who demonstrated that the expression of NK and NKT cells plays a major role in suppressing the development of A-MuLV-induced lymphomas in Tyk2−/− mice (Stoiber and others 2004).

Although NK cells, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells do not influence the ability of 4T1 cells to form tumors in a Tyk2-dependent manner, it appears that the ability of MDSCs to inhibit the growth of T cells is enhanced in the absence of Tyk2. It remains unclear whether the expression of Tyk2 in MDSCs is solely responsible for altering the rate of 4T1 cell tumor growth and metastasis, or the expression of Tyk2 in other cells plays a role in inhibiting tumor progression. It is possible that decreased IFNγ production observed in tumors and the splenocytes of Tyk2−/− mice also contributes to the inhibitory effects of Tyk2. IFNγ mediates its antitumor effects through activation of Stat1, and Stat1 does play an important role in immune surveillance (Koebel and others 2007). It is interesting to note that levels of Stat1 are decreased in a variety of tissues in Tyk2−/− mice and the ability of IFNγ to stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 is also diminished (Karaghiosoff and others 2000; Shimoda and others 2000). Since Stat1 and IFNγ play important roles in tumor-immune-system interactions, it is likely that Tyk2 expression also affects the ability of the immune system to respond to tumor challenge (Dunn and others 2005, 2006).

There is no evidence that mutations in Tyk2 might predispose to tumor formation. However, one can envisage such a scenario. In addition to mutations that abolish the kinase activity of Tyk2, mutations may occur in the protein that partially affect the ability of IL-12 to induce T cell production of IFNγ, which plays a pivotal role in promoting antitumor responses. In addition to mutations that modify kinase activity of Tyk2, other mutations in the protein that prevent it from associating with type 1 IFN or IL-12 receptors (FERM domain mutations) could account for naturally occurring defects in Tyk2 function. Screens to identify such defects in patients with a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, might be informative in terms of both prognosis and appropriate treatment.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Carron C. Cormier F. Janin A. Lacronique V. Giovannini M. Daniel MT. Bernard O. Ghysdael J. TEL-JAK2 transgenic mice develop T-cell leukemia. Blood. 2000;95(12):3891–3899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danial NN. Losman JA. Lu T. Yip N. Krishnan K. Krolewski J. Goff SP. Wang JYJ. Rothman PG. Direct interaction of Jak1 and v-Abl is required for v-Abl-induced activation of STATs and proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(11):6795–6804. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danial NN. Pernis A. Rothman PB. Jak-STAT signaling induced by the v-abl oncogene. Science. 1995;269:1875–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.7569929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP. Ikeda H. Bruce AT. Koebel C. Uppaluri R. Bui J. Chan R. Diamond M. White JM. Sheehan KC. Schreiber RD. Interferon-gamma and cancer immunoediting. Immunol Res. 2005;32(1–3):231–245. doi: 10.1385/ir:32:1-3:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GP. Koebel CM. Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(11):836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI. Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide H. Nakagawa T. Terado Y. Kamiyama Y. Muto S. Horie S. Tyk2 expression and its signaling enhances the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369(2):292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaghiosoff M. Neubauer H. Lassnig C. Kovarik P. Schindler H. Pircher H. McCoy B. Bogdan C. Decker T. Brem G. Pfeffer K. Muller M. Partial impairment of cytokine responses in Tyk2-deficient mice. Immunity. 2000;13:549–560. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebel CM. Vermi W. Swann JB. Zerafa N. Rodig SJ. Old LJ. Smyth MJ. Schreiber RD. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature. 2007;450(7171):903–907. doi: 10.1038/nature06309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics R. Passamonti F. Buser AS. Teo SS. Tiedt R. Passweg JR. Tichelli A. Cazzola M. Skoda RC. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacronique V. Boureux A. Valle VD. Poirel H. Quang CT. Mauchauffe M. Berthou C. Lessard M. Berger R. Ghysdael J. Bernard OA. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science. 1997;278(5341):1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Animal models of tumor immunity, immunotherapy and cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(2):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda K. Kato K. Aoki K. Matsuda T. Miyamoto A. Shibamori M. Yamashita M. Numata A. Takase K. Kobayashi S. Shibata S. Asana Y. Gondo H. Sekiguchi K. Nakayama K. Nakayama T. Okamura T. Okamura S. Niho Y. Nakayama K. Tyk2 plays a restricted role in IFNa signaling, although it is required for IL-12-mediated T cell function. Immunity. 2000;13:561–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber D. Kovacic B. Schuster C. Schellack C. Karaghiosoff M. Kreibich R. Weisz E. Artwohl M. Kleine OC. Muller M. Baumgartner-Parzer S. Ghysdael J. Freissmuth M. Sexl V. TYK2 is a key regulator of the surveillance of B lymphoid tumors. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(11):1650–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI22315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Turkson J. Carter-Su C. Smithgall T. Levitzki A. Kraker A. Krolewski JJ. Medveczky P. Jove R. Activation of Stat3 in v-Src-transformed fibroblasts requires cooperation of Jak1 kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(32):24935–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]