Abstract

Objectives

In 2001 the United Nations (UN) Declaration of Commitment was signed by 189 countries with a goal to reduce HIV prevalence among young people by 25% by 2010. Progress towards this target is assessed. In addition, changes in reported sexual behaviour among young people aged 15–24 years are investigated.

Methods

Thirty countries most affected by HIV were invited to participate in the study. Trends in HIV prevalence among young antenatal clinic (ANC) attendees were analysed using data from sites that were consistently included in surveillance between 2000 and 2008. Regression analysis was used to determine if the UN target had been reached. Trends in prevalence data from repeat national population-based surveys were also analysed. Trends in sexual behaviour were analysed using data from repeat standardised national population-based surveys between 1990 and 2008.

Results

Seven countries showed a statistically significant decline of 25% or more in HIV prevalence among young ANC attendees by 2008, in rural or urban areas or in both: Botswana, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia and Zimbabwe. Three further countries showed a significant decline in HIV prevalence among young women (Zambia) or men (South Africa, Tanzania) in national surveys. Seven other countries are on track, whereas four are unlikely to reach the goal by 2010. Nine countries did not have adequate data to assess prevalence trends. Indications suggestive of changes towards less risky sexual behaviour were observed in the majority of countries. In eight countries with significant declines in HIV prevalence, significant changes were also observed in sexual behaviour in either men or women for at least two of the three sexual behaviour indicators.

Conclusions

Declines in HIV prevalence among young people were documented in the majority of countries with adequate data and in most cases were accompanied by changes in sexual behaviour. Further data, research and more rigorous analysis at country level are needed to understand the associations between programmatic efforts, reported behavioural changes and changes in prevalence and incidence of HIV.

Keywords: HIV prevalence, sexual behaviour, time trends, young people

Considerable progress has been made towards scaling up access to HIV treatment, care and support with approximately 1 million people newly receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low and middle income countries in 2008.1 However, the estimated global number of new infections remains unacceptably high at approximately 2.7 million in 2008.2

A primary goal of the global response to HIV is to prevent new infections. To date, HIV prevalence data have been used to monitor trends in the HIV epidemic, but the rapid improvements in providing ART to people in need and the resulting increase in survival times are making it more difficult to rely on prevalence data only. Incidence data (or the rate at which new infections occur) are more valuable as they provide a more sensitive measure for evaluating changes in the HIV epidemic over time and for measuring the impact of interventions on infection levels.

There are three main approaches to determine HIV incidence in populations: direct measurement in cohort studies; mathematical inference from prevalence measurements; or using biological assays for recent infection in cross-sectional surveys. Following cohorts of uninfected individuals until seroconversion is often regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for measuring the incidence of infection or disease. However, these studies are typically conducted in small areas only, are logistically difficult to carry out, and are subject to bias because of the selection of initial participants and those remaining in the cohort and because of the effect of intensified interventions in the cohort. Several statistical and mathematical models to estimate HIV incidence using prevalence data and assumptions about mortality have been described and are regularly applied in countries.3–7 Several biological assays and testing strategies based on HIV antigen, RNA or antibody measurement have also been developed over recent years to distinguish recent from established HIV infections.8 9 Whereas some of these methods have been used in several settings across the world, work still needs to be done to validate and calibrate assays and algorithms for estimating incidence from cross-sectional collection of blood specimens.10

Trends in HIV prevalence in a population of newly exposed individuals could be regarded as a reasonable proxy for assessing trends in HIV incidence, despite several limitations.11 Prevalent infections among young people aged 15–24 years are assumed to be recent because the onset of sexual activity in this age group is recent. In addition, mortality effects in this age group are typically small so that trends in HIV prevalence are more likely to reflect trends in incidence rather than trends in mortality.12

In 2001, 189 member states signed the Declaration of Commitment at the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on AIDS, and committed to achieving a 25% reduction in HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old people in the 25 most affected countries by 2005 and globally by 2010 (UNGASS indicator number 22).13

This study assesses progress towards this UNGASS target. In countries most affected by the epidemic, changes in HIV prevalence among young pregnant women aged 15–24 years attending antenatal clinics (ANC) are analysed, as recommended in the guidelines for monitoring the UNGASS indicators.14 In addition, changes in HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old women and men participating in repeated national population-based surveys (referred to as ‘HIV prevalence surveys’ in the remainder of this paper) are analysed. Changes in sexual behaviour among young people, as reported in national population-based behavioural surveys conducted over time (referred to as ‘behavioural surveys’ in the remainder of this paper), are also analysed and an assessment is made of the concordance of HIV prevalence trends and sexual behaviour trends.

Methods

Prevalence data

All countries with an estimated national adult HIV prevalence of greater than 2% in the general population in 20072 were invited to participate in this study. Data on HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old pregnant women included in ANC surveillance were collated for statistical analysis of prevalence trends. To avoid potential bias as a result of expanding ANC surveillance over time, only data from those sites that were consistently included in surveillance between 2000 and 2008 were included in the analysis. In South Africa, data were only available aggregated at the provincial level and not by individual site, so that the provincial level trend data were included in the analysis.

Exponential trend lines were fitted to prevalence data for each country using data collected from sites that were consistently included in sentinel surveillance during the period of interest (2000–8), first to assess whether there have been changes in HIV prevalence over recent years and second to assess if these changes are statistically significant. The regression analysis was done only for those countries where prevalence data were available for a minimum of three points in time during the 2000–8 period. The analysis was conducted separately for urban and rural sites whenever data were available. For two countries (Angola and South Africa) the analysis was done at the national level only, whereas for Mozambique it was done for each of the three regions (south, central, north). For each country, the percentage change in fitted prevalence was calculated between the first and last year for which data were available. The slope of the curve was considered significantly different from zero for a p value of less than 0.05. Country data are shown for a selection of countries in the technical annexe and are available from the authors on request.

For countries that have conducted two or more national HIV prevalence surveys between 2000 and 2008, the HIV prevalence among 15–24-year-old men and women was taken from the published survey reports and compared between the different survey years. Prevalence surveys included AIDS indicator surveys (Botswana, Kenya and Tanzania; available at http://www.measuredhs.com), demographic and health surveys (Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe; available at http://www.measuredhs.com), large national household surveys (Burundi, South Africa),15–19 and a national survey on HIV and sexual health among young adults in Zimbabwe in 2001/2.20 χ2 Tests were performed to assess whether differences in prevalence were statistically significant at p<0.05.

Behavioural data

Three indicators on sexual behaviour recommended for monitoring and reporting of the 2001 UNGASS14 were analysed to assess changes in behaviour over time. These indicators are: (1) the percentage of young people aged 15–19 years who reported having had sexual intercourse by the age of 15 years; (2) the percentage of young men and women aged 15–24 years who reported having had sexual intercourse with more than one partner in the past 12 months; (3) the percentage of those young men and women aged 15–24 years who had more than one partner in the past 12 months and reported having used a condom during the last sex act.

Data for the above indicators were obtained from behavioural surveys conducted between 1990 and 2008. The period for assessment of trends in behavioural indicators was longer than that for assessment of HIV prevalence trends as current changes in HIV prevalence might be associated with behaviour change some years earlier. To ensure consistency of the data collection methodology and the definition of the indicators, only data from demographic and health surveys (available at http://www.measuredhs.com) or multiple indicator cluster surveys (available at http://www.unicef.org), or the repeated national population-based surveys conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council in South Africa17–19 were used in this analysis.

For countries with more than one behavioural survey, the average annual rate of decline/increase was calculated for each behaviour indicator by country. The statistical significance of changes over time was assessed using a χ2 test of association for those countries where only two surveys had been conducted, or a χ2 test for trend for those countries where more than two surveys had been conducted during the time period of interest. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Available data

Available data are summarised in table 1. Thirty countries with estimated adult prevalence greater than 2% in 2007 were invited to contribute HIV prevalence data for 15–24-year-old pregnant women attending ANC, of which 26 responded positively. Five of the countries that responded either did not have the required site-specific data for young women (Cameroon and Djibouti) or did not have data for at least three points in time during the 2000–8 period (Central African Republic, Chad and Gabon) and were therefore not eligible for the regression analysis. Among the 21 eligible countries, the overall time period for which HIV prevalence data were available ranged from 9 years (eg, Bahamas, Malawi, Côte d'Ivoire) to 4 years (Angola). The number of times surveillance was done in a country over the 2000–8 period (yearly data points), varied from a minimum of three to a maximum of nine times. In addition, table 1 shows the variation between countries in the number of sites that were consistently included in surveillance efforts over time.

Table 1.

Available data on HIV prevalence and behaviour among young people aged 15–24 years over time in countries with national adult prevalence of 2% or greater in 2007

| Country | Adult HIV prevalence in 2007 (%) (as per the 2008 Global Report)2 | Repeat national HIV prevalence surveys conducted since 2000 | Prevalence available from ANC surveillance: years in which surveillance was done | No of sites that were consistently included in ANC surveillance urban/rural | Behavioural data collected from young men and women (15–24 years) in national surveys | |||

| Age of first sex by the age of 15 years (among those aged 15–19 years) | Condom use during last sex act among those with multiple partners in past 12 months | Sexual intercourse with more than one partner in past 12 months | ||||||

| Angola | 2.1 | 2004, 2005, 2007 | 18 (national) | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Bahamas | 3.0 | Every year 2000–8 | 8 | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Belize | 2.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Botswana | 23.9 | 2004, 2008 | 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006 | 10 | 13 | NA | NA | NA |

| Burundi | 2.0 | 2002, 2007 | Every year 2000–7 | 4 | 4 | 1987, 2005 | NA | NA |

| Cameroon | 5.1 | NA | 1998, 2004, 2006 | 1998, 2004 | 1998, 2004 | |||

| CAR | 6.3 | 2006 | 1994, 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | |||

| Chad | 3.5 | 2002, 2003 | 1997, 2004 | 1997, 2004 | 1997, 2004 | |||

| Congo | 3.5 | NA | 2005 | 2005 | 2005 | |||

| Cote d'Ivoire | 3.9 | 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2008 | 11 | 16 | 1994, 1998, 2005 | 1998, 2005 | 1998, 2005 | |

| Djibouti | 3.1 | NA by site | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Ethiopia | 2.1 | 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005 | 20 | 9 | 2000, 2005 | 2000, 2005 | 2000, 2005 | |

| Gabon | 5.9 | 2003, 2007 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | |||

| Guyana | 2.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Haiti | 2.2 | 2000, 2004, 2007 | 8 | 9 | 1994, 2000, 2005 | 2000, 2005 | 2000, 2005 | |

| Kenya | 7.1–8.5 | 2003, 2007 | Every year 2000–5 | 21 | 13 | 1993, 1998, 2003 | 1998, 2003 | 1998, 2003 |

| Lesotho | 23.2 | 2003, 2005, 2007 | 2 | 8 | 2004 | 2004 | 2004 | |

| Malawi | 11.9 | 1999, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2007 | 11 | 8 | 2000, 2004, 2006 | 2000, 2004 | 2000, 2004 | |

| Mozambique | 12.5 | 2001, 2002, 2004, 2007 | 11 (south), 16 (central), 11 (north) | 1997, 2003 | 2003 | 2003 | ||

| Namibia | 15.3 | 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008 | 13 | 8 | 1992, 2000, 2006 | 2000, 2006 | 2000, 2006 | |

| Nigeria | 3.1 | 2003, 2005, 2008 | 87 | 75 | 1990, 1999, 2003 | 2003 | 2003 | |

| Rwanda | 2.8 | 2002, 2003, 2005, 2007 | 11 | 13 | 1992, 2000, 2005 | NA | 2000, 2005 | |

| South Africa | 18.1 | 2002, 2005, 2008 | Every year 2000–7 | Aggregated for nine provinces | NA | 2002, 2005, 2008 | 2002, 2005, 2008 | |

| Suriname | 2.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Swaziland | 26.1 | 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008 | 9 | 8 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | |

| Togo | 3.3 | 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008 | 18 | 16 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Uganda | 5.4 | 2000, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2006, 2007 | 9 | 11 | 1995, 2000, 2004, 2006 | 1995, 2000, 2006 | 1995, 2000, 2006 | |

| UR Tanzania | 6.2 | 2003–4, 2007 | 2002, 2004, 2006 | 24 | 33 | 1992, 1996, 1999, 2004, 2007 | 1996, 1999, 2004, 2007 | 1996, 1999, 2004, 2007 |

| Zambia | 15.2 | 2002, 2007 | 2002, 2004, 2006 | 11 | 11 | 1992, 1996, 2002, 2007 | 1996, 2002, 2007 | 1996, 2002, 2007 |

| Zimbabwe | 15.3 | 2002, 2006 | 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006 | 7 | 7 | 1994, 1999, 2005 | 1999, 2005 | 1999, 2005 |

ANC, antenatal clinic; NA, not available.

Seven countries (Botswana, Burundi, Kenya, South Africa, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) had repeated national HIV prevalence surveys for which HIV prevalence data were available on 15–24-year-old men and women. Repeat behavioural survey data were available to conduct trend analysis of the three behavioural indicators for 17, 14, and 12 countries, respectively (table 1). Information was available for all three indicators in 12 countries. In Rwanda, the sample sizes were too small to compare condom use among those who reported having had multiple sex partners in the past year. In South Africa, data were only available on the percentage of young people reported having had multiple sex partners, whereas in Mozambique data were only available on the percentage of young people reported to have had sex by the age of 15 years. In Burundi and the Central African Republic, additional multiple indicator cluster surveys allowed comparison of the percentage of young people reported to have had sex by age 15 years.

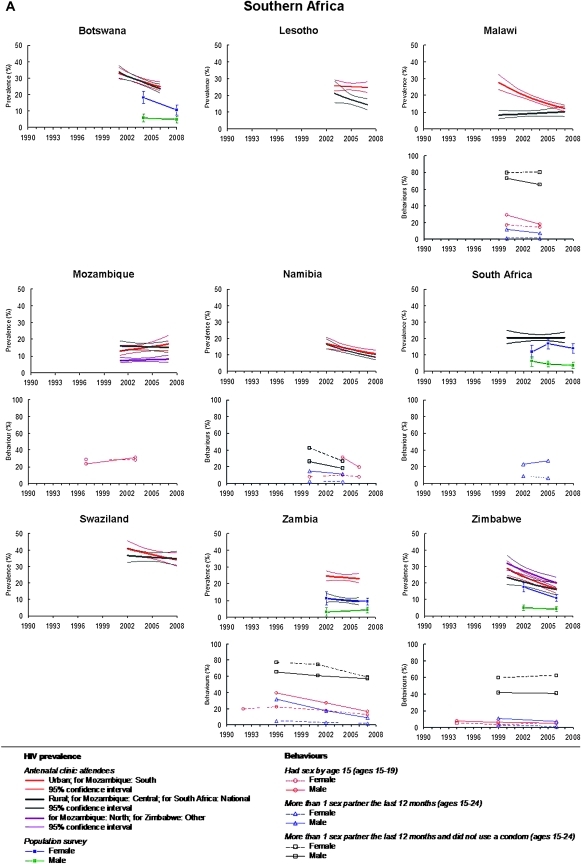

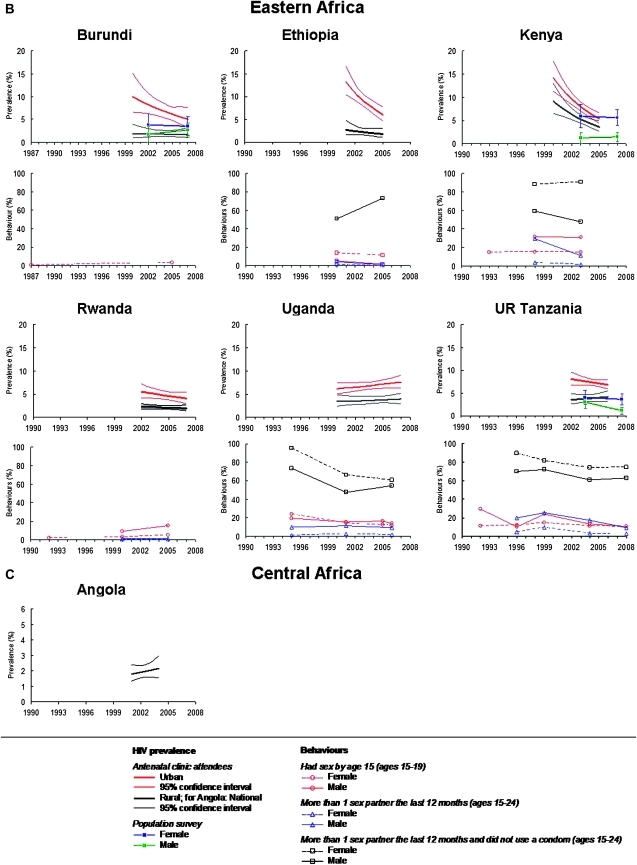

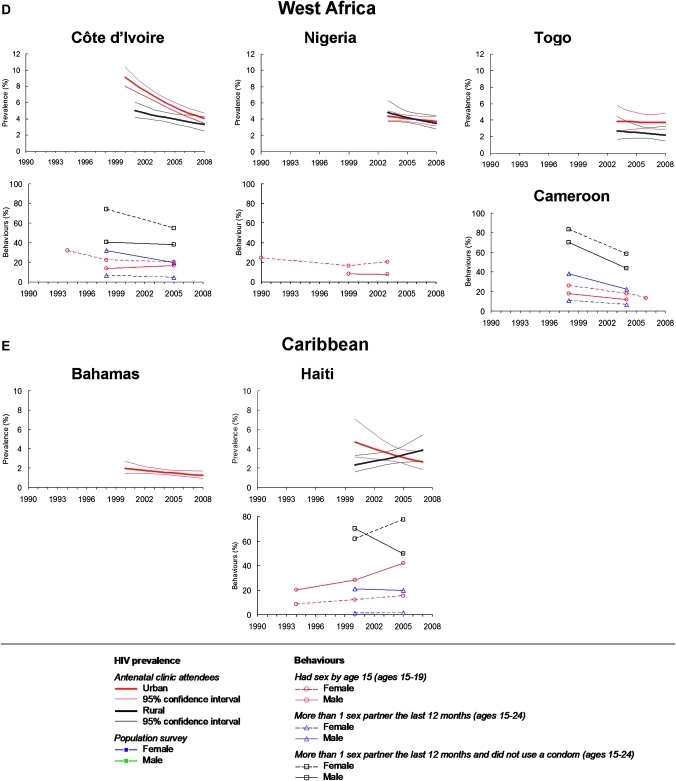

HIV prevalence trends

HIV prevalence trends among 15–24-year-old pregnant women showed a decline in either urban or rural areas in 17 of the 21 participating countries (figure 1, table 2). Thirteen countries showed a reduction in HIV prevalence of 25% or more between 2000 and 2008 in either urban or rural areas or both, with statistically significant results in Kenya between 2000 and 2005 (more than 60% change in both urban and rural areas, p<0.01), urban Ethiopia between 2001 and 2005 (55% change, p<0.01), urban Malawi between 1999 and 2007 (56% change, p<0.01), Namibia between 2002 and 2008 (urban change 37%, p<0.01; rural change 48%, p<0.01), Zimbabwe between 2000 and 2006 (urban change 43%, p<0.01; rural change 32%, p<0.05), Botswana between 2001 and 2006 (urban change 25%, p<0.01; rural change 30%, p<0.01) and Côte d'Ivoire between 2000 and 2008 (urban change 56%, p<0.01; rural change 35%, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Trends in HIV prevalence and selected sexual behaviour indicators among young men and women aged 15–24 years in (A) southern Africa, (B) east Africa, (C) central Africa, (D) west Africa and (E) the Caribbean.

Table 2.

Analysis of HIV prevalence data from young women aged 15–24 years attending ANC using sites that were consistently included in surveillance over time

| Region | Country | Period of assessment* | Predicted prevalence† | % Change in predicted prevalence from first to last year of assessment period | p Value | |||

| First year | Last year | First year | Last year | |||||

| East Africa | Burundi | Urban | 2000 | 2007 | 9.9 | 5.0 | 49.2 | 0.065 |

| Rural | 2000 | 2007 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 0.928 | ||

| Ethiopia | Urban | 2001 | 2005 | 13.2 | 6.0 | 54.5 | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 2001 | 2005 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 35.0 | 0.347 | ||

| Kenya | Urban | 2000 | 2005 | 14.2 | 5.4 | 62.2 | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 2000 | 2005 | 9.2 | 3.6 | 61.0 | 0.001 | ||

| Tanzania | Urban | 2002 | 2006 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 15.5 | 0.204 | |

| Rural | 2002 | 2006 | 3.5 | 4.2 | −17.9 | 0.487 | ||

| Rwanda | Urban | 2002 | 2007 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 26.2 | 0.199 | |

| Rural | 2002 | 2007 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 14.2 | 0.517 | ||

| Uganda | Urban | 2000 | 2007 | 6.1 | 7.6 | −23.3 | 0.183 | |

| Rural | 2000 | 2007 | 3.4 | 3.9 | −15.7 | 0.581 | ||

| Southern Africa | Botswana | Urban | 2001 | 2006 | 32.9 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 0.003 |

| Rural | 2001 | 2006 | 33.6 | 23.6 | 29.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Lesotho | Urban | 2003 | 2007 | 25.8 | 24.7 | 4.0 | 0.704 | |

| Rural | 2003 | 2007 | 21.1 | 14.3 | 32.3 | 0.090 | ||

| Malawi | Urban | 1999 | 2007 | 27.6 | 12.2 | 55.8 | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 1999 | 2007 | 8.2 | 10.1 | −22.6 | 0.443 | ||

| Mozambique | South | 2001 | 2007 | 12.9 | 17.1 | −32.2 | 0.166 | |

| Central | 2001 | 2007 | 15.9 | 15.2 | 4.6 | 0.774 | ||

| North | 2001 | 2007 | 7.3 | 8.1 | −10.9 | 0.588 | ||

| Namibia | Urban | 2002 | 2008 | 16.9 | 10.6 | 37.1 | 0.007 | |

| Rural | 2002 | 2008 | 16.4 | 8.5 | 48.0 | <0.001 | ||

| South Africa | National | 2000 | 2007 | 20.5 | 20.4 | 0.3 | 0.983 | |

| Swaziland | Urban | 2002 | 2008 | 40.8 | 33.9 | 16.9 | 0.058 | |

| Rural | 2002 | 2008 | 36.6 | 34.7 | 5.1 | 0.600 | ||

| Zambia | Urban | 2002 | 2006 | 24.5 | 23.2 | 5.6 | 0.545 | |

| Rural | 2002 | 2006 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 17.3 | 0.301 | ||

| Zimbabwe | Urban | 2000 | 2006 | 28.9 | 16.4 | 43.1 | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 2000 | 2006 | 23.4 | 15.9 | 31.7 | 0.044 | ||

| Other | 2000 | 2006 | 31.9 | 20.2 | 36.8 | 0.001 | ||

| Central Africa | Angola | National | 2004 | 2007 | 1.8 | 2.2 | −21.2 | 0.440 |

| West Africa | Cote d'Ivoire | Urban | 2000 | 2008 | 9.1 | 4.9 | 56.0 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 2001 | 2008 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 34.8 | 0.028 | ||

| Nigeria | Urban | 2003 | 2008 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 15.2 | 0.151 | |

| Rural | 2003 | 2008 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 27.4 | 0.110 | ||

| Togo | Urban | 2003 | 2008 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.872 | |

| Rural | 2003 | 2008 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 18.8 | 0.576 | ||

| Caribbean | Bahamas | Urban | 2000 | 2008 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 37.1 | 0.090 |

| Haiti | Urban | 2000 | 2007 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 44.6 | 0.061 | |

| Rural | 2000 | 2007 | 2.3 | 3.8 | −67.2 | 0.080 | ||

The period of assessment indicates the period for which country-specific surveillance data were available between 2000 and 2008.

Predicted prevalence from regression analysis.

ANC, antenatal clinic.

Of the seven countries with repeated HIV prevalence surveys, all except South Africa showed a decline in HIV prevalence among young women over time, whereas only four showed a decline among young men (table 3). In Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe, the prevalence decline among women was statistically significant (Botswana from 18.2% in 2004 to 10.7% in 2008, p<0.0001; Zambia from 11.2% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2007, p=0.018; Zimbabwe from 17.4% in 2002 to 10.9% in 2006, p<0.001), whereas in Tanzania and South Africa the decline among young men was statistically significant (Tanzania from 3% in 2003 to 1.1% in 2007, p<0.001; South Africa from 6.1% in 2003 to 3.6% in 2008, p=0.005). In most instances the significant reductions exceeded 25%. In South Africa, the overall trend in prevalence observed among young women participating in national surveys between 2002 and 2008 was not statistically significant. However, prevalence during this period first increased from 12% in 2002 to 16.7% in 2005, then declined to 13.9% in 2008, and could therefore suggest a decline in incidence as shown elsewhere.21

Table 3.

HIV prevalence among young men and women aged 15–24 years from repeat national population-based surveys

| Country | Year of survey | Type of survey | Females 15–24 years | p Value | Males 15–24 years | p Value | ||||

| n | Prevalence (%) | SE | n | Prevalence (%) | SE | |||||

| Botswana | 2004 | BAIS II | 1593 | 18.2 | 1.93 | <0.001 | 1480 | 5.8 | 1.22 | 0.225 |

| 2008 | BAIS III | 1476 | 10.7 | 1.61 | 1338 | 4.8 | 1.17 | |||

| Burundi | 2002 | Household | 923 | 3.8 | 1.26 | 0.737 | 871 | 1.7 | 0.88 | 0.119 |

| 2007 | Household | 1306 | 3.5 | 1.02 | 1736 | 2.7 | 0.78 | |||

| Kenya | 2003 | DHS | 1369 | 5.9 | 1.27 | 0.681 | 1311 | 1.2 | 0.60 | 0.647 |

| 2007 | AIS | 2926 | 5.6 | 0.85 | 2209 | 1.4 | 0.50 | |||

| South Africa | 2002 | HSRC | 1123 | 12 | 1.94 | 0.825 | 976 | 6.1 | 1.53 | 0.005 |

| 2005 | HSRC | 2334 | 16.7 | 1.55 | 1785 | 4.4 | 0.97 | |||

| 2008 | HSRC | 1986 | 13.9 | 1.55 | 1631 | 3.6 | 0.92 | |||

| UR Tanzania | 2003.5 | AIS | 2388 | 4 | 0.80 | 0.402 | 2084 | 3 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| 2007.5 | AIS | 3286 | 3.6 | 0.65 | 2940 | 1.1 | 0.38 | |||

| Zambia | 2002 | DHS | 940 | 11.2 | 2.06 | 0.018 | 675 | 3 | 1.31 | 0.125 |

| 2007 | DHS | 2225 | 8.5 | 1.18 | 2027 | 4.3 | 0.90 | |||

| Zimbabwe | 2001.5 | Young adult survey | 3197 | 17.4 | 1.34 | <0.001 | 2760 | 5 | 0.83 | 0.179 |

| 2005.5 | DHS | 3200 | 10.9 | 1.10 | 2939 | 4.3 | 0.74 | |||

AIS, AIDS indicator survey; BAIS, ; DHS, demographic and health survey; HSRC, Human Sciences Research Council.

Behavioural trends

A reduction in the proportion of 15–19-year olds with early sexual debut was observed among women and men in 13/17 (statistically significant in eight) and 11/16 (statistically significant in seven) countries, respectively, as shown in table 4 and figure 1. In four countries (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Malawi and Zambia), the decrease was significant in both women and men.

Table 4.

Percentage of young people aged 15–19 years who reported having had sexual intercourse by the age of 15 years

| Country | Year of survey | Females | p Value | Males | p Value | ||||

| n | % | Decline per year (%) | n | % | Decline per year (%) | ||||

| Burundi | 1987 | 1000 | 0.7 | ||||||

| 2005* | 2357 | 3.1 | −8.27 | <0.001 | |||||

| Cameroon | 1998 | 1282 | 26.0 | 539 | 17.8 | ||||

| 2004 | 2685 | 18.0 | 1224 | 11.5 | 7.28 | 0.0004 | |||

| 2006* | 2016 | 13.4 | 7.79 | <0.001 | |||||

| Central African Republic | 1994* | 1288 | 24.6 | 321 | 16.0 | ||||

| 2006* | 2572 | 27.0 | −0.78 | 0.114 | 860 | 11.7 | 2.61 | 0.056 | |

| Chad | 1997 | 1716 | 21.9 | 490 | 7.9 | ||||

| 2004 | 1361 | 19.0 | 2.03 | 0.045 | 406 | 10.7 | −4.33 | 0.174 | |

| Cote D'Ivoire | 1994 | 1961 | 31.9 | ||||||

| 1998 | 775 | 22.1 | 180 | 13.8 | |||||

| 2005 | 1232 | 20.4 | 3.73 | <0.001 | 898 | 16.7 | −2.72 | 0.349 | |

| Ethiopia | 2000 | 3710 | 13.5 | 600 | 5.1 | ||||

| 2005 | 3266 | 11.1 | 3.91 | 0.002 | 1335 | 1.7 | 21.97 | <0.001 | |

| Haiti | 1994 | 1290 | 8.4 | 350 | 20.1 | ||||

| 2000 | 2342 | 12.0 | 768 | 28.3 | |||||

| 2005 | 2701 | 15.3 | −5.47 | <0.001 | 1211 | 41.9 | −6.65 | <0.001 | |

| Kenya | 1993 | 1754 | 14.9 | ||||||

| 1998 | 1851 | 15.0 | 811 | 31.7 | |||||

| 2003 | 1856 | 14.5 | 0.27 | 0.739 | 856 | 30.9 | 0.51 | 0.747 | |

| Malawi | 2000 | 2867 | 16.5 | 660 | 29.1 | ||||

| 2004 | 2392 | 14.1 | 650 | 18.0 | 12.01 | <0.001 | |||

| 2006* | 5196 | 13.9 | 3.01 | 0.001 | |||||

| Mozambique | 1997 | 1836 | 28.6 | 382 | 23.5 | ||||

| 2003 | 2454 | 27.7 | 0.35 | 0.666 | 673 | 31.1 | −4.62 | 0.009 | |

| Namibia | 1992 | 1259 | 7.7 | ||||||

| 2000 | 1499 | 9.8 | 694 | 31.3 | |||||

| 2006 | 2246 | 7.4 | 0.11 | 0.589 | 910 | 19.2 | 8.15 | <0.001 | |

| Nigeria | 1990 | 1612 | 24.4 | ||||||

| 1999 | 1775 | 16.2 | 511 | 8.3 | |||||

| 2003 | 1716 | 20.3 | 1.90 | <0.001 | 453 | 7.9 | 1.23 | 0.877 | |

| Rwanda | 1992 | 1464 | 2.1 | ||||||

| 2000 | 2617 | 3.0 | 762 | 9.3 | |||||

| 2005 | 2585 | 5.2 | −6.7 | <0.001 | 1102 | 15.3 | −9.96 | <0.001 | |

| UR Tanzania | 1992 | 2183 | 11.4 | 499 | 29.6 | ||||

| 1996 | 1732 | 12.3 | 488 | 10.4 | |||||

| 1999 | 909 | 14.5 | 790 | 23.9 | |||||

| 2004 | 2245 | 11.4 | 637 | 13.0 | |||||

| 2007.5 | 1984 | 10.7 | 0.62 | 0.285 | 1768 | 10.8 | 4.83 | <0.001 | |

| Uganda | 1995 | 1606 | 23.8 | 387 | 19.2 | ||||

| 2000.5 | 1615 | 14.2 | 441 | 15.5 | |||||

| 2004.5 | 2186 | 12.2 | 2069 | 16.3 | |||||

| 2006 | 1936 | 11.8 | 6.48 | <0.001 | 595 | 13.9 | 2.39 | 0.096 | |

| Zambia | 1992 | 1984 | 19.4 | ||||||

| 1996 | 2003 | 21.7 | 460 | 39.3 | |||||

| 2001.5 | 1811 | 17.5 | 459 | 27.2 | |||||

| 2007 | 1574 | 12.3 | 3.30 | <0.001 | 1416 | 16.2 | 8.06 | <0.001 | |

| Zimbabwe | 1994 | 1472 | 5.2 | 604 | 7.9 | ||||

| 1999 | 1447 | 3.2 | 713 | 6.3 | |||||

| 2005.5 | 2152 | 4.9 | 0.17 | 0.994 | 1899 | 5.2 | 3.60 | 0.013 | |

Results from multiple indicator cluster survey.

A reduction in the proportion of 15–24-year old with multiple partners in the past 12 months was found in 10/14 (significant in seven) and 13/14 (significant in 10) countries for women and men, respectively (table 5, figure 1). In seven countries (Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia. Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) there was a significant reduction in both men and women.

Table 5.

Percentage of young men and women aged 15–24 years who reported having had sexual intercourse with more than one partner in the past 12 months

| Country | Females | Males | |||||||

| Year of survey | n | % | Decline per year (%) | p Value | n | % | Decline per year (%) | p Value | |

| Cameroon | 1998 | 2409 | 10.6 | 1067 | 38.3 | ||||

| 2004 | 4937 | 6.6 | 7.90 | <0.001 | 2177 | 22.4 | 8.94 | <0.001 | |

| Chad | 1997 | 3084 | 1.2 | 863 | 22.9 | ||||

| 2004 | 2432 | 1.0 | 2.60 | 0.453 | 673 | 12.0 | 9.23 | <0.001 | |

| Cote D'Ivoire | 1998 | 1353 | 6.7 | 338 | 32.1 | ||||

| 2005 | 2360 | 4.5 | 5.69 | 0.003 | 1836 | 19.7 | 6.97 | <0.001 | |

| Ethiopia | 2000 | 6570 | 1.1 | 1007 | 4.3 | ||||

| 2005 | 5813 | 0.1 | 47.96 | <0.001 | 2399 | 0.9 | 31.28 | <0.001 | |

| Haiti | 2000 | 4260 | 1.2 | 1280 | 21.2 | ||||

| 2005 | 4704 | 1.5 | −4.46 | 0.203 | 2104 | 19.8 | 1.37 | 0.343 | |

| Kenya | 1998 | 3399 | 3.4 | 1400 | 29.5 | ||||

| 2003 | 3547 | 1.6 | 15.08 | <0.001 | 1537 | 11.3 | 19.19 | <0.001 | |

| Malawi | 2000 | 5825 | 1.0 | 1259 | 11.8 | ||||

| 2004 | 5262 | 1.1 | −2.38 | 0.583 | 1237 | 7.0 | 13.05 | <0.001 | |

| Namibia | 2000 | 2838 | 2.3 | 1304 | 14.8 | ||||

| 2006 | 4101 | 2.2 | 0.74 | 0.791 | 1661 | 11.1 | 4.79 | 0.0025 | |

| Rwanda | 2000 | 4524 | 0.3 | 1195 | 1.2 | ||||

| 2005 | 4938 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.960 | 2048 | 1.0 | 3.65 | 0.599 | |

| South Africa | 2002 | 634 | 8.8 | 517 | 23.0 | ||||

| 2005 | 1397 | 6.0 | 972 | 27.2 | |||||

| 2008 | NA | 6.0 | 6.4 | NS* | NA | 30.8 | −4.9 | NS* | |

| Tanzania | 1996 | 3408 | 4.7 | 859 | 19.8 | ||||

| 1999 | 1720 | 9.8 | 1330 | 25.2 | |||||

| 2004 | 4252 | 3.1 | 1130 | 17.2 | |||||

| 2007.5 | 3730 | 2.5 | 8.42 | <0.001 | 2196 | 9.3 | 6.87 | <0.001 | |

| Uganda | 1995 | 3162 | 1.1 | 754 | 9.7 | ||||

| 2000.5 | 3119 | 2.3 | 762 | 11.1 | |||||

| 2006 | 3646 | 1.7 | −3.96 | 0.078 | 996 | 9.3 | 0.38 | 0.738 | |

| Zambia | 1996 | 3834 | 4.6 | 863 | 31.8 | ||||

| 2002 | 3476 | 2.4 | 804 | 17.6 | |||||

| 2007 | 2944 | 1.5 | 10.21 | <0.001 | 2482 | 8.8 | 11.62 | <0.001 | |

| Zimbabwe | 1999 | 2741 | 1.8 | 1219 | 10.8 | ||||

| 2005.5 | 4104 | 0.9 | 10.5 | 0.001 | 3358 | 7.1 | 6.45 | <0.001 | |

Denominators not available. Significant levels as reported in 2008 Human Sciences Research Council survey report

Finally, a reduced proportion of young people not using condoms was seen in six out of 11 (significant in six) and 11/12 (significant in five) countries for women and men, respectively (table 6, and figure 1). Significant increases in condom use in both sexes occurred in Cameroon and Uganda.

Table 6.

Percentage of young people aged 15–24 years who had more than one partner in the past 12 months and reported having used a condom during the last sex act

| Country | Females | Males | |||||||

| Year of survey | n | % | Decline per year (%) | p Value | n | % | Decline per year (%) | p Value | |

| Cameroon | 1998 | 255 | 17 | 408 | 30 | ||||

| 2004 | 328 | 41.6 | 14.91 | <0.001 | 489 | 56.3 | 10.49 | <0.001 | |

| Chad | 1997 | 36 | 17.4 | 197 | 21.8 | ||||

| 2004 | 50 | 9.1 | −9.26 | 0.334 | 163 | 26.3 | 2.68 | 0.313 | |

| Cote D'Ivoire | 1998 | 91 | 25.8 | 109 | 59.2 | ||||

| 2005 | 106 | 45.1 | 7.98 | 0.004 | 361 | 61.8 | 0.61 | 0.638 | |

| Ethiopia | 2000 | 74 | 18 | 44 | 49.3 | ||||

| 2005 | 6 | 22 | 27 | −12.04 | 0.078 | ||||

| Haiti | 2000 | 51 | 38 | 271 | 29.7 | ||||

| 2005 | 70 | 22.6 | −10.39 | 0.072 | 418 | 50.5 | 10.62 | <0.001 | |

| Kenya | 1998 | 117 | 11.9 | 413 | 40.6 | ||||

| 2003 | 57 | 9.1 | −5.37 | 0.526 | 174 | 52.1 | 4.99 | 0.009 | |

| Malawi | 2000 | 60 | 20.3 | 148 | 26.8 | ||||

| 2004 | 60 | 19.9 | −0.50 | 1 | 87 | 34.5 | 6.31 | 0.215 | |

| Namibia | 2000 | 66 | 57.4 | 192 | 73.8 | ||||

| 2006 | 91 | 73.7 | 4.17 | 0.035 | 184 | 82.2 | 1.80 | 0.058 | |

| Tanzania | 1996 | 159 | 10 | 170 | 29.9 | ||||

| 1999 | 168 | 18.2 | 335 | 28.1 | |||||

| 2004 | 130 | 25.8 | 195 | 39.2 | |||||

| 2007.5 | 93 | 25.4 | 7.82 | <0.001 | 272 | 36.9 | 2.60 | 0.012 | |

| Uganda | 1995 | 35 | 4.5 | 73 | 26.6 | ||||

| 2000.5 | 53 | 33.8 | 85 | 52.8 | |||||

| 2006 | 63 | 39.4 | 19.72 | 0.001 | 93 | 45.2 | 4.82 | 0.022 | |

| Zambia | 1996 | 176 | 23.2 | 274 | 34.7 | ||||

| 2001 | 85 | 25.3 | 141 | 39.1 | |||||

| 2007 | 43 | 41.5 | 5.38 | 0.026 | 218 | 43.1 | 1.96 | 0.056 | |

| Zimbabwe | 1999 | 50 | 40.2 | 132 | 58.1 | ||||

| 2005.5 | 37 | 37.9 | −0.91 | 0.838 | 237 | 59.4 | 0.34 | 0.782 | |

Association of prevalence and behavioural trends

Of the 11 countries that had trends established for both HIV prevalence and behaviour (for at least two indicators), eight countries showed a significant HIV prevalence reduction whereas three did not. All eight of the countries with a decline in prevalence also had favourable trends in behaviours (defined as a significant trend in either men or women for at least two of the three behavioural indicators) that overlapped or started before the period of prevalence decline: Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Of the three countries that did not have a significant decline in HIV prevalence, Uganda showed favourable trends in behaviours whereas Haiti and Rwanda did not.

Discussion

The UNGASS ANC clinic attendees by 2005 was reached by Botswana, Côte d'Ivoire (urban areas), Ethiopia (urban areas), Kenya, Malawi (urban areas) and Zimbabwe, as well as by South African men included in the 2002 and 2005 surveys. By 2008, Namibia and Côte d'Ivoire (rural areas) also showed a significant reduction in HIV prevalence of over 25% among ANC attendees, as did Tanzanian men and Zambian women included in national surveys. Seven other countries (Burundi (urban areas), Lesotho (rural areas), Nigeria (rural areas), Rwanda, Swaziland (urban areas), Bahamas and Haiti (urban areas)) seem to be on track to reach the UNGASS target of a significant 25% reduction by 2010. Two countries seem unlikely to achieve a 25% reduction in prevalence by 2010 as HIV prevalence did not show a decline during the study period (Angola, Mozambique). In addition, Uganda, after significant declines in prevalence in the 1990s, showed an increase, although not statistically significant, in HIV prevalence among young women attending ANC between 2000 and 2007. Finally, five of the 26 countries that responded to the invitation to participate in this study currently do not have enough data to allow an assessment of the HIV prevalence trends.

Mathematical modelling suggests that trends in HIV prevalence in 15–24-year-old ANC attendees approximate trends in this age group in the general population, although the former may be slow to reflect declines in the latter when there is a concomitant increase in age at first sex.11 A recent study in Manicaland, Zimbabwe (unpublished data), provides the first empirical evidence corroborating this relationship. Modelling work also indicates that trends in HIV prevalence in 15–24-year olds can approximate trends in HIV incidence in the same age group.11 If so, the declines in HIV prevalence in ANC attendees observed in this study may reflect declines in HIV incidence in the general community. In the current study, Botswana and Zimbabwe show significant (>25%) declines in HIV prevalence among women in both ANC surveillance and HIV prevalence surveys. In Zimbabwe, the downward trend in prevalence in young people has also been observed in a cohort study in Manicaland province and modelling of national prevalence data suggests that there have been important reductions in incidence during the early part of the current decade.22 23 In Botswana, a decline in prevalence among young women attending ANC was recently also reported elsewhere,24 but unfortunately Botswana does not have the benefit of an independent community-based cohort study. Other countries show significant declines in only one source of prevalence data, suggesting that infection rates may have been decreasing less strongly. In some instances, declines were observed only among one of the sexes or only in urban or rural areas. In Zambia and Tanzania, independent application of a mathematical model to HIV prevalence data from repeat national surveys also showed significant declines in incidence among women and men, respectively.25

While the restriction of the prevalence analysis to young people aged 15–24 years allows the interpretation of HIV prevalence trends being parallel to trends in incidence in this age group, the same restriction prevents any inference about incidence trends in other age groups. Data from several community-based studies in sub-Saharan Africa grouped in the ALPHA network suggest that recent patterns in HIV incidence among older people may be different from those among young people.26 Neither can HIV prevalence data among 15–24-year olds inform trends in HIV incidence among children, although independent analyses indicate that incidence among children has also been declining in recent years,2 mainly as a result of increased access to prevention of mother-to-child-transmission services. It is possible that a small percentage of children infected with HIV through mother-to-child transmission survive into their teens27 and become part of the HIV prevalence among 15–24-year olds. However, the scale-up of prevention of mother-to-child-transmission programmes is too recent1 to have contributed to a decrease in prevalence among 15–24-year olds during 2000–8.

Declines in HIV incidence can occur as part of the natural course of an HIV epidemic. Individuals with the highest risk behaviour in a population are usually infected rapidly during the early years of an epidemic. Subsequently, HIV incidence falls because those who have not been infected previously typically have relatively less risky behaviour.28 29 By focussing the current HIV prevalence analysis on 15–24-year olds and on the period 2000–8, which for most countries is at least a decade after the start of the epidemic, these natural history effects should largely have been avoided—ie, because those aged 15–24 years during 2000–8 were from a different birth cohort to those aged 15–24 years during the first decade of the epidemic. The HIV incidence declines implied by the reductions in HIV prevalence among 15–24-year olds recorded here are unlikely to be due to the natural history of the epidemic.

The current analysis has focused on comparable behavioural indicators by restricting the analysis to data of standardised surveys, which are believed to allow a reliable assessment of trends in behaviour.30 Behavioural indicators can provide corroboration of changes in HIV incidence and assist in attributing changes to particular aspects of risk.31 32 Because of data limitations and the analytical approach, the current analysis cannot establish a causal association between changes in sexual behaviour and trends in HIV prevalence. However, it is encouraging that in the current analysis, most countries with HIV prevalence declines also show positive changes in sexual behaviour. Data collected on sexual behaviour over time may be subject to reporting bias, including social desirability bias, as prevention programmes can change the social norms regarding sexual behaviour.33 In addition, where there is mixing across age groups, behaviour changes in older people, particularly men, could cause reductions in prevalence in young people. The extent to which changes in HIV prevalence have been brought about by behavioural change programmes is beyond the scope of this paper, but needs to be investigated through further in-depth research and modelling, as has been done for Zimbabwe.23 34

In conclusion, this multicountry analysis of data from the 30 countries most affected by the AIDS epidemic reveals several important findings. First, of the 21 countries that have data to assess national trends in HIV prevalence among 15–24-year olds in recent years, the majority show declines in HIV prevalence, and in 10 countries statistically significant declines of more than 25% have occurred. Second, the declines in HIV prevalence are likely to be the result of declines in HIV incidence. Third, in most countries with prevalence declines, declines in risky sexual behaviours were also observed. Fourth, looking towards the 2010 UNGASS targets, there is a need to strengthen programmes to monitor trends in HIV prevalence, incidence and sexual behaviours, both in countries that have solid surveillance systems, and more urgently in countries that currently have insufficient data. All countries included in this analysis should consider conducting national surveys that measure both HIV prevalence and sexual behaviours at regular time intervals (eg, every 4 or 5 years).35 Finally, country-based evaluations should be conducted, drawing on an even larger set of quantitative and qualitative data sources to corroborate the trends found in this analysis and to study the relation between programmatic efforts and the observed behavioural and epidemiological changes.

Key messages.

HIV prevalence among young people aged 15–24 years declined significantly between 2000 and 2008 in 10 of 21 high burden countries.

Changes towards less risky sexual behaviour have been observed among young men and women in the majority of countries included in this analysis.

In the majority of countries with significant declines in HIV prevalence, significant changes were also observed in sexual behaviour in either men or women.

Programmes to monitor trends in HIV prevalence, incidence and sexual behaviour should be strengthened.

More data and further analysis are needed to understand the associations between prevention efforts, behavioural changes and changes in the prevalence and incidence of HIV.

Acknowledgments

E Fadriquela (UNAIDS Geneva); M Gomes (Angola); F Gomez (Botswana); A Bamba-Louguet (Central African Republic); PE Ehounoud, LR Lobognon (Côte d'Ivoire); I Mohammed (Djibouti); C Fontaine (Ethiopia); B Olivia, R Nze Eyo'o (Gabon); E Louissaint, E Pierre, S Morisseau, C Desforges, F Carl, C Alzuphar, LM Boulous (Haiti); G Haile (Kenya); P Chikukwa (Malawi); M Mahy, M Oditt (Namibia); H Damisoni, J Sagbohan (Nigeria); E Pegurri (Rwanda); H Damisoni (South Africa); K Takpa (Togo); W Kirungi (Uganda); M Kibona, F Macha, J Nankinga, A Gavyole, A Chaddy (UR Tanzania); E Sattin (Zambia).

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: EG, PDG and RL wrote the first draft of the paper. BB provided data on sexual behaviour collected from national population based surveys. Country collaborators provided country-specific data on HIV prevalence and contributed to the country-specific analysis of trend data. EG performed the final statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the final draft of the paper.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF Towards universal access. Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Progress report 2009. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2008. http://www.unaids.org (accessed 11 Nov 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallett T, Zaba B, Todd J, et al. Estimating incidence from prevalence in generalised HIV epidemics: methods and validation. PLoS Med 2008;5:e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregson S, Donnelly CA, Parker CG, et al. Demographic approaches to the estimation of incidence of HIV-1 infection among adults from age-specific prevalence data in stable endemic conditions. AIDS 1996;10:1689–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams B, Gouws E, Wilkinson D, et al. Estimating HIV incidence rates from age prevalence data in epidemic situations. Stat Med 2001;20:2003–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown T, Salomon JA, Alkema L, et al. Progress and challenges in modelling country-level HIV/AIDS epidemics: the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package 2007. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84(Suppl 1):i5–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stover J, Johnson P, Zaba B, et al. The Spectrum projection package: improvements in estimating mortality, ART needs, PMTCT impact and uncertainty bounds. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84(Suppl 1):i24–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parekh BS, McDougal JS. Application of laboratory methods for estimation of HIV-1 incidence. Indian J Med Res 2005;121:510–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen RS, Satten GA, Stramer SL, et al. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. JAMA 1998;280:42–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO WHO Technical HIV Incidence Assay Working Group. http://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/links/hiv_incidence_assay/en/index1.html (accessed 18 Oct 2009).

- 11.Zaba B, Boerma T, White R. Monitoring the AIDS epidemic using HIV prevalence data among young women attending antenatal clinics: prospects and problems. AIDS 2000;14:1633–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghys PD, Kufa E, George MV. Measuring trends in prevalence and incidence of HIV infection in countries with generalised epidemics. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82(Suppl 1):i52–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. New York: United Nations, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS Monitoring the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS: guidelines on construction of core indicators: 2008 reporting. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centre de Formation et de Recherche en Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses (CEFORMI) Enquete combinee de surveillance des comportements face au VIH/SIDA/IST et d'estimation de la seroprevalence du VIH/SIDA au Burundi. Burundi: CEFORMI/IMEA, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etude réalisée par le Centre de Formation et de Recherche en Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses (CEFORMI) Enquete nationale de seroprevalence de l'infection par le VIH au Burundi. Bujumbura: Ministère de la Sante Publique, Ministère à la Présidence Chargé de la Lutte contre le Sida, Banque Mondiale, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shisana O, Simbayi L. Nelson Mandela/HSRC study of HIV/AIDS: South African national HIV prevalence, behavioural risks and mass media household survey 2002. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2005. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: a turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health and Child Welfare Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe National Family Planning Council, National AIDS Council Zimbabwe, and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Zimbabwe young adult survey 2001–2002. Harare, Zimbabwe: Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rehle TM, Hallett TB, Shisana O, et al. A decline in new HIV infections in South Africa: estimating HIV incidence from three national HIV surveys in 2002, 2005 and 2008. PLoS One 2010;5:e11094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science 2006;311:664–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallett TB, Gregson S, Mugurungi O, et al. Assessing evidence for behaviour change affecting the course of HIV epidemics: a new mathematical modelling approach and application to data from Zimbabwe. Epidemics (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Gouws E, Stanecki KA, Lyerla R, et al. The epidemiology of HIV infection among young people aged 15–24 years in southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22(Suppl 4):S5–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallett TB, Stover J, Mishra V, et al. Estimates of HIV incidence from household-based prevalence surveys. AIDS 2010;24:147–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaba B, Todd J, Biraro S, et al. Diverse age patterns of HIV incidence rates in Africa. Oral Abstract TUAC0201. XVIIth International AIDS Conference. Mexico, August 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrand RA, Corbett EL, Wood R, et al. AIDS among older children and adolescents in southern Africa: projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. AIDS 2009;23:2039–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garnett GP, Gregson S, Stanecki KA. Criteria for detecting and understanding changes in the risk of HIV infection at a national level in generalised epidemics. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82(Suppl 1):i48–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallett TB, White PJ, Garnett GP. Appropriate evaluation of HIV prevention interventions: from experiment to full-scale implementation. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83(Suppl 1):i55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland J, Boerma JT, Carael M, et al. Monitoring sexual behaviour in general populations: a synthesis of lessons of the past decade. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slaymaker E. A critique of international indicators of sexual risk behaviour. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garnett GP, Garcia-Calleja JM, Rehle T, et al. Behavioural data as an adjunct to HIV surveillance data. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82(Suppl 1):i57–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, et al. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychol Bull 1990;108:339–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregson S, Gonese E, Hallett TB, et al. HIV decline in Zimbabwe due to reductions in risky sex? Evidence from a comprehensive epidemiological review. Int J Epidemiol 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance Guidelines for measuring national HIV prevalence in population based surveys. Geneva: UNAIDS and World Health Organization, 2005 [Google Scholar]