Abstract

Women and men differ in the way they experience emotional events. Previous work has indicated that the impact of an emotional event depends on how it is anticipated. Separately, it has been shown that anticipation affects memory formation. Here, we assessed whether anticipatory brain activity influences the encoding of emotional events into long-term memory and, in addition, how biological sex affects the use of such activity. Electrical brain activity was recorded from the scalps of healthy men and women while they performed an incidental encoding task (indoor/outdoor judgments) on pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. Pictures were preceded by a cue that indicated the valence of the upcoming item. Memory was tested after a 20 min delay with a recognition task incorporating the remember/know procedure. Brain activity before picture onset predicted later memory of an event. Crucially, the role of anticipatory activity depended entirely on the valence of a picture and the sex of an individual. Right-lateralized anticipatory activity selectively influenced the encoding of unpleasant pictures in women, but not in men. These findings indicate that anticipatory processes influence the way in which women encode negative events into memory. The selective use of such activity may indicate that anticipatory activity is one mechanism by which individuals regulate their emotions.

Introduction

The ability to adapt behavior in line with future events is essential to function optimally. From an evolutionary perspective, anticipating an aversive event may help an individual to prepare adaptive reactions in threatening situations. In everyday life, however, excessive anticipation of future harm may lead to psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression (Beck, 1967). The relevance of anticipation in the processing of emotional events is highlighted by a number of neuroimaging studies. Such studies have shown that emotion-related brain regions, including the anterior cingulate, amygdala, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, are already engaged before exposure to an emotional event (Simmons et al., 2004; Mackiewicz et al., 2006; Nitschke et al., 2006; Herwig et al., 2007). Notably, anticipatory activity in some of these regions correlates with self-reported anxiety levels (Nitschke et al., 2006; Simmons et al., 2006). This finding, coupled with the observation that brain activity in many of the above mentioned areas is altered in psychiatric disorders (Brody et al., 2001; Whiteside et al., 2004), suggests that dysfunction is partly associated with processes set in motion before the onset of an emotional event.

A separate line of research indicates that anticipatory activity plays a role in long-term memory formation. It has been shown that brain activity before an event can predict whether the event will later be remembered or forgotten (Adcock et al., 2006; Mackiewicz et al., 2006; Otten et al., 2006, 2010; Guderian et al., 2009; Gruber and Otten, 2010). Given that emotion strongly interacts with memory (Dolcos and Denkova, 2008), this raises the interesting possibility that anticipatory processes not only affect the perceptual intake of an emotional event, but also its encoding into long-term memory. Here, we tested this idea for the encoding of pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral events.

In particular, we focused on the use of anticipatory activity by men and women. Mackiewicz and colleagues (2006) have shown that anticipatory activity can affect the encoding of emotional events, but only unpleasant and neutral events were considered and no sex differences were observed. However, biological sex has a profound impact on the processing of emotional events (Andreano and Cahill, 2009). For example, sex differences occur in performance of emotional memory tasks (Hamann and Canli, 2004), in the perceptual anticipation of affective events (Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009), and in encoding-related activity following affective events (Canli et al., 2002). It may thus be expected that men and women differ in the way they use anticipatory activity to encode emotional memories. If so, this may highlight a mechanism by which the impact of emotional events is regulated.

Electrical brain activity was recorded while healthy adults performed an incidental encoding task on intermixed pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. A cue indicated the valence of an upcoming item. Activity preceding pictures was contrasted according to later recognition memory performance. The question of interest was how encoding-related activity differs depending on the emotional content of the approaching item and the sex of the individual.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Thirty volunteers (mean age = 20.7 years, SD = 1.5 years, 15 women) took part in the experiment. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and reported to be native English speaking, right-handed, and not to have a history of psychiatric or neurological illness. The experimental procedures were approved by the University College London Research Ethics Committee. Each participant provided written informed consent before participating and was remunerated at a rate of £7.50/h.

Stimulus materials.

We selected 510 pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) (Lang et al., 1997): 170 pleasant scenes, 170 unpleasant scenes, and 170 neutral scenes. According to the normative rating data of the IAPS, the three picture sets differed significantly in valence (one-way ANOVA, F(1.9, 313.4) = 4.64, p < 0.001). Valence ratings (on a scale from 1 to 9) varied between 1.3 and 3.6 for unpleasant pictures, 4.4 and 5.9 for neutral pictures, and 6.5 and 8.3 for pleasant pictures. We opted to use the same physical stimuli for all participants to avoid item-specific effects rather than take the small differences in IAPS valence ratings across men and women (Bradley and Lang, 2007) into consideration. Pleasant and unpleasant scenes were rated as equally arousing (t169 = −1.02, p = 0.30), and both as more arousing than neutral pictures (t169 = 26.81 and 28.59, respectively; both p < 0.001). For each valence set, five pictures were used to create practice lists. The remaining 165 pictures in each set were split into three groups of 55. Two of the groups were designated as old items and one as new items. The particular groups that were used as old and new items were counterbalanced across participants. Old pictures (110 pleasant, 110 unpleasant, and 110 neutral) were randomly allocated to a study list of 330 items. The test list consisted of 495 randomly allocated items—330 old pictures and 165 new pictures (55 pleasant, 55 unpleasant, and 55 neutral). Lists were randomized anew for each participant. Study lists were split into five blocks and test lists into eight blocks to provide brief rest periods.

Procedure.

The experiment involved an incidental encoding task followed by a recognition memory test. In the study phase, participants viewed a series of pictures, presented one at a time. Each picture was preceded by a cue that indicated whether the picture would depict a pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral scene. Cues were cartoon faces with upward, downward, and neutral mouths to signal pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral scenes, respectively. Participants were asked to decide whether a picture portrayed an indoor or outdoor scene and press one of two buttons with their right thumb or index finger to indicate their decision. Response finger was counterbalanced across participants. The instructions emphasized speed as well as accuracy, and indicated that the cue should be used to get ready for the upcoming picture. The latter instruction was used to encourage participants not to ignore cues.

The test phase followed the study phase after ∼20 min. Participants were only told that their memory would be tested at this point in the experiment. The memory test consisted of a recognition memory task, incorporating the remember/know procedure (Tulving, 1985). This procedure was used to restrict the neural comparisons to study items that were later remembered on the same basis (recollection or strong memory: Yonelinas, 2002; Wais et al., 2008). All the pictures from the study phase were presented again, intermixed with new pictures. As in the study phase, pictures were preceded by cues to indicate the valence of the upcoming item. This was done to keep the stimulus presentation parameters constant across study and test. For each picture, participants had three response options: remember, to be given if the picture brought back specific details from its occurrence in the study phase (such as what participants thought about when they first saw the picture); know, to be given if participants only had a general feeling that they had seen the picture in the study phase; and new, to be given if they thought that the picture had not been presented before. Each option was assigned to one of three response buttons, which had to be pressed with the index, middle, or ring finger of the right hand (response finger counterbalanced across participants). A brief practice block preceded the study and test phases to familiarize participants with the tasks. After finishing the test phase, participants completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1970). This test was administered to verify that participants fell within a normal anxiety range and to correlate anxiety level with encoding-related brain activity.

At both study and test, pictures were shown centrally on a computer screen on a gray background. Pictures subtended a visual angle of ∼6.8° horizontally and 5.1° vertically. Cues were presented 1.5 s before picture onset and remained on the screen until 100 ms before the picture was shown. Pictures were displayed for 1 s. The time between successive cue onsets varied randomly between 4.5 and 6 s at study and between 5 and 6.5 s at test. A fixation point (a black plus sign) was continuously present in the center of the screen except when cues and pictures were presented.

EEG acquisition and analysis.

EEG was recorded from 32 scalp sites with sintered silver/silver–chloride electrodes embedded in an elastic cap. Electrodes were positioned according to an equidistant montage (www.easycap.de/easycap/e/electrodes/13_M10.htm). Vertical and horizontal eye movements were recorded bipolarly from, respectively, electrodes attached to the supraorbital and infraorbital ridges of the right eye and to the outer canthus of each eye. A midfrontal site (corresponding to Fz in the 10/20 system) was used as the online reference. Impedances were kept <5 kΩ. On-line, signals were amplified, bandpass filtered between 0.01 and 35 Hz (3 dB roll-off), and digitized at a rate of 250 Hz (12-bit resolution). Off-line, the data were digitally filtered between 0.05 and 20 Hz with a 96 dB roll-off, zero phase shift filter. The data were then downsampled to 125 Hz and algebraically re-referenced to linked mastoids (reinstating the midfrontal on-line reference site).

The primary interest was in the role of anticipatory processes in the encoding of emotional memories. However, for completeness, we also computed encoding-related activity after picture onset. Activity elicited by cues and pictures was analyzed separately to allow each to be aligned to the time period immediately preceding each event (cf. Otten et al., 2006, 2010; Gruber and Otten, 2010). Epochs of 2048 ms duration surrounding cues and pictures, starting 100 ms before their onset, were extracted from the continuous record. Event-related potentials (ERPs) were computed for each participant and electrode site for pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures later given remember, know, and new judgments. The ERP waveforms were aligned to the 100 ms period before cue and picture onsets. This approach allowed us to assess whether pictures elicited encoding-related activity above and beyond any encoding-related activity elicited by cues. Blink artifacts were minimized by estimating and correcting their contribution to the ERP waveforms (Rugg et al., 1997). Trials with horizontal and nonblink vertical movements were excluded from the averaging process, as were trials containing drifts (±50 μV), amplifier saturation, or muscle artifacts.

Brain activity associated with successful memory encoding was identified with the subsequent memory procedure (Sanquist et al., 1980). ERP waveforms for pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral trials were contrasted depending on whether the pictures from those trials were remembered or forgotten in the later recognition memory task. The analyses focused on pictures later given remember versus new judgments. We used the remember/know paradigm to minimize the possibility that comparisons of encoding-related activity across valence and biological sex were confounded by type or strength of memory. We restricted the analyses to remember judgments because previous work has suggested that anticipatory encoding-related activity is more pronounced for items accompanied by recollection or strong memories (Otten et al., 2006, 2010; Gruber and Otten, 2010). In addition, only a subset of participants had at least 12 artifact-free trials for pictures later given know judgments (11 men and 13 women) and this response category was therefore not considered (an exploratory analysis did not reveal subsequent memory effects in this category). For cue-related activity giving rise to later remember judgments, mean trial numbers for remembered and forgotten items were 41 and 26 for pleasant, 45 and 27 for unpleasant, and 39 and 30 for neutral cues, respectively. For picture-related activity, the corresponding trial numbers were 42 and 25 for pleasant, 41 and 27 for unpleasant, and 40 and 28 for neutral pictures.

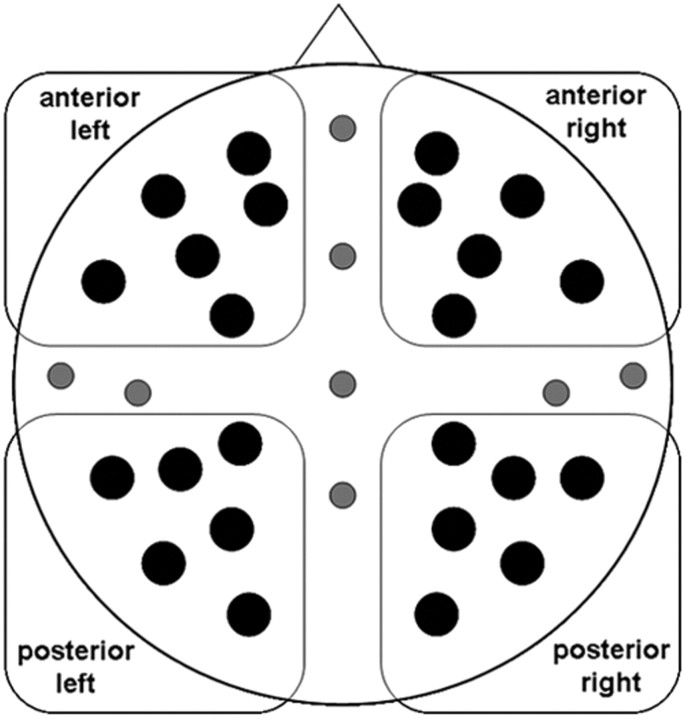

Waveforms were quantified by measuring mean amplitudes in latency regions that captured the effects visible in the group-averaged waveforms to assess consistency across participants (see Results, below). For both cue-related and picture-related activity, the analyses were performed on the maximum number of electrode sites out of the montage that allowed a balanced partitioning of sites into four quadrants on the scalp (Fig. 1). These quadrants were used to characterize scalp topography in terms of left/right asymmetry and anterior/posterior location. ERP amplitudes from 24 sites were submitted to mixed-model ANOVAs, incorporating factors of hemisphere (left/right), location (anterior/posterior), electrode site (six positions), and interval (three latencies) in addition to the experimental factors of subsequent memory (remembered/forgotten), valence (pleasant/unpleasant/neutral), and sex (men/women). Greenhouse–Geisser corrections for violations of sphericity were applied to all factors with more than two levels (Keselman and Rogan, 1980). Only effects involving subsequent memory were considered. In line with our a priori interests, we also computed ANOVAs in each valence category to assess the significance of subsequent memory effects in each category in men and women. We checked whether the multivariate approach to repeated measurements (Vasey and Thayer, 1987) would lead to different conclusions, but this was not the case for cue- or picture-elicited activity and therefore only the univariate analyses are reported.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the scalp sites used to record and analyze electrical brain activity. Activity was recorded from all 32 sites that are shown. The statistical analyses were based on the 24 black sites to allow partitioning of sites into four quadrants defined by anterior–posterior and left–right location.

Results

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Across participants, mean scores on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory were 31.0 (SD = 8.1) for state anxiety and 37.4 (SD = 12.2) for trait anxiety. These scores did not differ significantly between men and women (p > 0.41).

Task performance

Mean response time for indoor/outdoor judgments was 931 ms (SD = 284 ms) for pleasant pictures, 951 ms (SD = 301 ms) for neutral pictures, and 990 ms (SD = 282 ms) for unpleasant pictures. These times were compared with a mixed-model ANOVA with a repeated-measures factor of valence and a between-subjects factor of sex. A main effect of valence indicated that response times differed significantly across picture types (F(1.7, 46.7) = 16.04, p < 0.001). Responses to unpleasant pictures were slower than those to pleasant and neutral ones (t29 = −5.39 and 3.19, p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively), and responses to neutral pictures were in turn slower than those to pleasant ones (t29 = −2.33, p = 0.027). No interaction with biological sex emerged (p = 0.23). Given the subjective nature of many indoor/outdoor judgments, study accuracy was not considered.

The overall accuracy with which old pictures were discriminated from new pictures was similar regardless of emotional content (Table 1). Accuracy of recognition judgments was established with the discrimination index Pr (the proportion of hits minus the proportion of false alarms; Snodgrass and Corwin, 1988). Pr values were submitted to a mixed-model ANOVA with factors of valence and sex. No significant effects emerged. Mimicking the ERP analyses below, the analyses were then restricted to pictures given remember judgments. This time, the ANOVA on the discrimination indices revealed a significant main effect of valence (F(1.7, 48.4) = 6.02, p = 0.007). Accuracy of remember judgments was lower for pleasant pictures compared with unpleasant and neutral ones (t29 = −3.78 and −2.94, p = 0.001 and 0.006, respectively), which did not differ from each other (p = 0.88). The lower discrimination accuracy seems mainly driven by the higher false alarm rate for pleasant pictures. None of the analyses on the data from the recognition memory test revealed interactions involving sex (p > 0.48).

Table 1.

Proportions of responses in the recognition memory task

| Recognition type | Picture type |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasant | Unpleasant | Neutral | |

| Hits, remember | 0.42 (0.16) | 0.45 (0.17) | 0.40 (0.18) |

| Hits, know | 0.31 (0.15) | 0.27 (0.13) | 0.29 (0.14) |

| Misses | 0.27 (0.11) | 0.28 (0.13) | 0.31 (0.12) |

| Correct rejections | 0.75 (0.13) | 0.81 (0.11) | 0.84 (0.10) |

Standard deviations are displayed in parentheses.

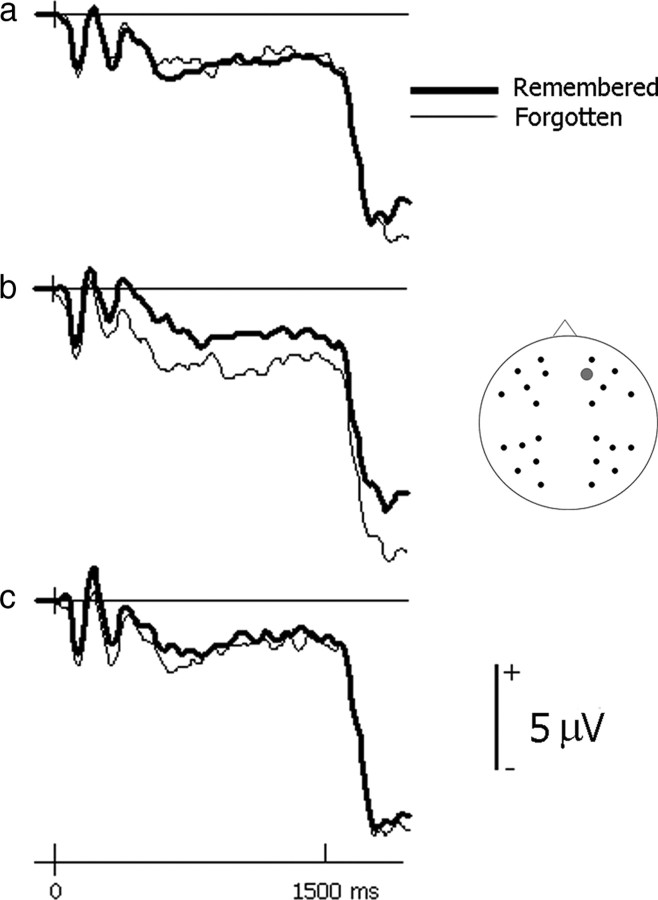

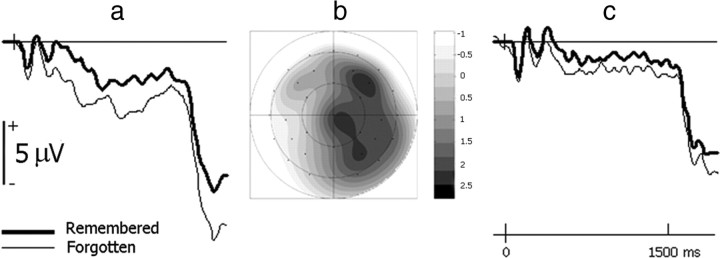

Anticipatory activity related to encoding

Electrical brain activity before picture onset differed depending on the type of recognition judgment a picture later received (Fig. 2). Activity elicited by cues indicating an upcoming unpleasant picture was more positive-going from an early point onwards when the picture was later given a remember rather than new judgment. Strikingly, this effect was only evident in women (Fig. 3). In men, anticipatory activity did not differ appreciably depending on the type of memory judgment. Similarly, only small differences are evident in encoding-related activity preceding pleasant and neutral pictures in both women and men.

Figure 2.

Anticipatory brain activity predicting later memory performance. a–c, Depicted are group-averaged ERP waveforms (collapsed across men and women) at a frontal electrode site (site 21 from montage 10; www.easycap.de/easycap/e/electrodes/13_M10.htm) elicited by cues preceding pleasant pictures (a), unpleasant pictures (b), and neutral pictures (c). Anticipatory activity related to successful encoding is evident for unpleasant cues. For graphical purposes, the waveforms were low-pass filtered at 19.4 Hz.

Figure 3.

Anticipatory brain activity elicited by cues preceding unpleasant pictures separated according to the biological sex of the individual. a, c, In women (a), but not men (c), anticipatory activity is predictive of later memory performance. Waveforms are shown for the same frontal scalp site as used in Figure 2. For graphical purposes, the waveforms were low-pass filtered at 19.4 Hz. b, Voltage spline map illustrating that the effect in women is largest over right hemisphere scalp sites. The map shows the difference between activity preceding later remembered and forgotten pictures in the 300–1500 ms interval following cue onset.

These effects were quantified by measuring mean amplitude values in the 300–700, 700–1100, and 1100–1500 ms intervals following cue onset. Encoding-related activity preceding unpleasant pictures in women is evident from ∼300 ms after cue onset, persisting until picture onset. Separating this interval into three allowed us to assess possible differences in amplitude or scalp distribution over time. ERP amplitudes from 24 sites were submitted to a mixed-model ANOVA that incorporated the between-subjects factor of sex (men/women) and within-subjects factors of subsequent memory (remembered/forgotten), valence (pleasant/unpleasant/neutral), interval (300–700/700–1100/1100–1500 ms), location (anterior/posterior), hemisphere (left/right), and electrode site (six positions; Fig. 1). This ANOVA gave rise to a significant interaction between valence, subsequent memory, hemisphere, and location (Greenhouse–Geisser corrected F(1.9, 55.5) = 3.28, p = 0.045). However, the interaction between subsequent memory, hemisphere, and location was not significant for any valence category (p > 0.32). Crucially, the mixed-model ANOVA also showed a highly significant interaction between valence, subsequent memory, sex, and hemisphere (F(1.9, 54.3) = 5.66, p = 0.006). The comparisons in each valence category indicated that the interaction between subsequent memory, sex, and hemisphere was significant for unpleasant pictures (F(1,28) = 20.29, p < 0.001), whereas no effects involving subsequent memory emerged for pleasant or neutral pictures (p > 0.12). For unpleasant pictures, ERP amplitudes before stimulus onset were more positive-going in women at right scalp sites when the pictures were later remembered (F(1,14) = 11.06, p = 0.005). No significant effects emerged for unpleasant pictures in men (p > 0.10). None of the above analyses demonstrated interactions involving the interval factor (p > 0.28).

A correlational analysis was performed to assess whether the encoding-related anticipatory activity found for unpleasant stimuli in women varied as a function of anxiety level. To that end, women's state and trait anxiety scores were correlated with the amplitude of the anticipatory ERP effect they displayed in the 300–1500 ms interval (averaged across right hemisphere scalp sites). No significant correlation emerged (p > 0.18).

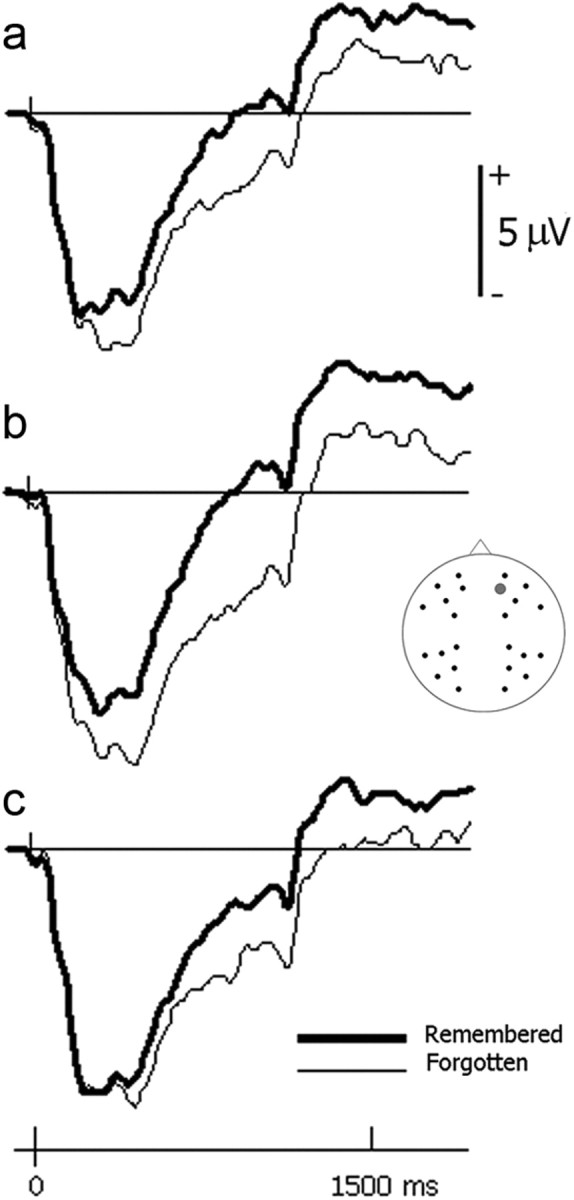

Encoding-related activity after picture onset

Activity following picture onset also differed as a function of later memory performance (Fig. 4). As typically observed (Friedman and Johnson, 2000), items that were later remembered elicited more positive-going waveforms than items that were later forgotten. These effects were quantified in the 200–600, 600–1100, and 1100–1900 ms intervals. Again, effects are visible throughout this period of time, but partitioning the period allowed an assessment of differences over time. The same mixed-model ANOVA as performed on the cue data revealed a significant interaction between subsequent memory and interval (F(1.5, 43.9) = 20.31, p < 0.001). Subsequent memory effects were significant in all three intervals, however (200–600 ms: F(1.0, 29.0) = 7.62, p = 0.010; 600–1100 ms: F(1.0, 29.0) = 34.35, p < 0.001; 1100–1900 ms: F(1.0, 29.0) = 27.23, p < 0.001). There was also an interaction between subsequent memory and location (F(1.0, 28.0) = 30.17, p < 0.001). Confirming the well known anterior location of stimulus-elicited encoding-related activity, subsequent memory effects were significant at anterior (F(1.0, 29.0) = 49.21, p < 0.001) but not posterior (p = 0.058) scalp locations. Crucially, no interactions between subsequent memory and either valence or sex emerged in any of these analyses.

Figure 4.

Brain activity following picture onset. a–c, Group-averaged ERP waveforms (collapsed across men and women) are shown for pleasant pictures (a), unpleasant pictures (b), and neutral pictures (c) that were later remembered or forgotten. The frontal electrode site used in Figures 2 and 3 is shown again here (site 21 from montage 10; www.easycap.de/easycap/e/electrodes/13_M10.htm). A positive-going, frontally distributed subsequent memory effect is elicited by all picture types. Waveforms were low-pass filtered at 19.4 Hz for display purposes.

Discussion

The data support the notion that brain activity engaged in anticipation of an emotional event influences the effectiveness with which the event is encoded into long-term memory. Scalp-recorded electrical brain activity elicited by a cue that signaled the imminent presentation of an emotional scene predicted whether that scene would later be remembered. This activity must therefore be relevant for successful memory formation (Paller and Wagner, 2002). This was only true, however, when the upcoming picture depicted an unpleasant scene (cf. Mackiewicz et al., 2006). The anticipation of an adverse event is vital from an evolutionary perspective. Knowing that a potentially threatening situation is about to arrive enables the engagement of preparatory mechanisms to help deal with the impact of the situation. Indeed, neuroimaging studies have shown an overlap between brain regions active before and after aversive events (Simmons et al., 2004; Mackiewicz et al., 2006; Nitschke et al., 2006; Herwig et al., 2007). Here, we show that preparatory mechanisms not only affect the perception of an emotional event (Simmons et al., 2004; Nitschke et al., 2006; Herwig et al., 2007), but also its encoding into long-term memory. Perhaps consistent with an adaptive account, we did not find anticipatory activity predictive of successful encoding for neutral or pleasant pictures. On this account, there would be less need to prepare because of the absence of an imminent threat.

Crucially, neural responses in anticipation of unpleasant events were found in women, but not in men. Sex differences in emotional memory have consistently been reported (Hamann and Canli, 2004). Men and women appear to activate different brain regions when encoding unpleasant events, including the right amygdala in men and left amygdala in women (Canli et al., 2002). A common explanation of such results refers to hemispheric specialization, building on the idea that lateralized cognitive processes are engaged differentially by men and women (Canli et al., 2002). It is not possible to infer the intracerebral location of the generator(s) of scalp-recorded activity on the basis of scalp distribution alone. However, it is interesting to note that anticipatory activity in the present study was right lateralized in women. At first glance, this may appear to contradict the abovementioned studies. However, our results show brain responses related to the anticipation of an emotional picture and not the processing of the picture itself.

It is stereotypically thought that women are more emotionally responsive than men, and this has also received empirical support (Bradley et al., 2001; Gard and Kring, 2007). The current findings suggest that such enhanced responsivity extends to the anticipation of unpleasant events, affecting their encoding into long-term memory. One possibility is that the right-lateralized anticipatory activity we observed reflects a vigilance bias toward threatening information. A role of the right hemisphere in vigilance bias has been noted in previous studies (Mogg et al., 2000). For two reasons, however, this seems unlikely. First, vigilance bias has been associated with high anxiety (Eysenck, 1992; Derakshan and Eysenck, 2001), but anxiety levels were within a normal range here and there was no differences between women and men. Second, previous ERP work on vigilance bias has implicated negative slow potentials over anterior scalp sites rather than right-lateralized positive activity (Carretié et al., 2004).

The anticipatory activity may instead reflect specific emotional strategies engaged by women to cope with the expectation of an unpleasant event. Upon anticipation of an unpleasant event, women may spontaneously engage strategies to counter the impact of negative emotions. It has indeed been reported that men and women regulate their emotions differently. Emotion regulation in men seems to be a fast and automatic process (McRae et al., 2008), whereas women generally use more emotional coping styles when confronted with negative information (Matud, 2004). Sex differences in emotion regulation are also well documented at the neural level (Mak et al., 2009; Domes et al., 2010). If women employ distinct emotional coping styles, these may first emerge during the anticipation of an event.

In this respect, it is worth noting the nature of anticipatory activity observed in the present experiment. This activity took the form of a more positive-going waveform preceding pictures that were later remembered. This effect resembles the anticipatory activity seen for words in a monetary reward paradigm (Gruber and Otten, 2010). Reward and emotion may both elicit motivational processes (Lang et al., 1998), which may give rise to positive-going anticipatory activity. In contrast, the negative-going anticipatory activity observed over anterior locations in semantic encoding tasks (Otten et al., 2006, 2010) may reflect cognitively oriented preparatory processes.

Although speculative, the suggested link between anticipatory brain activity, memory formation, and the regulation of emotions envisions improvements in the understanding of psychiatric disorders involving dysfunctions of emotional memory. The use of dysfunctional emotion regulatory strategies has been related to the higher prevalence of affective disorders in women (Thayer et al., 2003). Anxiety disorders, for example, are characterized by emotion regulation deficiencies (Amstadter, 2008) and memory biases toward negative emotional content (McNally, 1997). If the anticipatory activity we observed is associated with emotional regulation, the activity might be expected to be accompanied by differences in mood state or anxiety level (cf. Nitschke et al., 2006; Simmons et al., 2006). We did not find a correlation between anticipatory activity and trait or state anxiety in the present study. As noted previously, however, all anxiety scores fell within a normal and relatively narrow range. It remains to be determined whether individuals with pathological levels of anxiety cope with the anticipation of an unpleasant event in a dysfunctional way, affecting the way the event is encoded. If so, instructions to regulate emotions before, and not only during, exposure to an aversive event may help reduce the impact of the event.

As typically observed, we found positive-going encoding-related activity after picture onset over anterior scalp locations (Paller and Wagner, 2002). In striking contrast with anticipatory activity, picture-elicited activity did not differ depending on valence or sex of the individual. This emphasizes the importance of anticipation in the encoding of emotional events and suggests that activity before an event is dissociable from activity thereafter (cf. Otten et al., 2006, 2010; Gruber and Otten, 2010). Previous fMRI studies did find sex and valence differences during the encoding of emotional pictures (Canli et al., 2002; Cahill et al., 2004; Mackiewicz et al., 2006) and demonstrated an overlap in emotion-related brain regions before and after picture onset (Simmons et al., 2004; Mackiewicz et al., 2006; Nitschke et al., 2006; Herwig et al., 2007). Although these discrepant results may reflect methodological differences, it is also possible that the relatively slow time course of hemodynamic activity is not able to capture the fast changing encoding processes surrounding event onset.

Three aspects of the present work deserve further consideration. First, the selective influence of encoding-related activity preceding unpleasant events cannot be explained by differences in arousal. We carefully matched emotional pictures for arousal using the IAPS ratings (Lang et al., 1997). If arousal were the main determinant of our results, similar activity for pleasant and unpleasant pictures should have been observed. Second, the neural differences between men and women were not accompanied by differences in picture responding or memory performance. Although this may just be a reflection of differential sensitivity of neural and performance measures, sex differences in brain activity in the absence of behavioral differences have been observed in a number of cognitive domains (Grabowski et al., 2003; Piefke et al., 2005; Andreano and Cahill, 2009). It has been suggested that men and women employ different, but equally effective, cognitive strategies. Alternatively, performance differences may only arise in the context of sex-related traits (e.g., masculinity) rather than biological sex (Cahill et al., 2004). Third, men showed a small encoding-related effect before unpleasant pictures in the same direction as women (Fig. 3c). Although this was not statistically significant, it may suggest that women and men differ quantitatively, rather than qualitatively, in the way they prepare for an upcoming unpleasant event.

A limitation of the present study is that we cannot say what kind of memory is associated with anticipatory encoding-related activity. The remember/know paradigm was devised to separate recognition based on recollection and familiarity (Tulving, 1985). Given that anticipatory activity was found for remember responses, it is tempting to suggest that anticipatory processes are especially important for episodic memory (cf. Otten et al., 2010; Gruber and Otten, 2010). However, both memory strength and memory type contribute to the differentiation between remember and know judgments (Yonelinas, 2002; Wais et al., 2008) and activity associated with know judgments could not be considered here. Understanding the type of memory associated with preparatory processes in emotional memory therefore awaits further experimentation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that anticipatory brain activity influences the encoding of negative, but not positive, emotional information. Crucially, this activity only affected memory encoding in women. Anticipatory activity may be one mechanism by which individuals regulate their emotions. Cognitive strategies to reduce anxiety, such as emotion regulation, might target anticipatory processes in addition to the response to the emotional event itself.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 084618/Z/08/Z to L.J.O. Stimulus presentation was programmed with the Cogent2000 software of the physics group of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adcock RA, Thangavel A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Knutson B, Gabrieli JD. Reward-motivated learning: mesolimbic activation precedes memory formation. Neuron. 2006;50:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreano JM, Cahill L. Sex influences on the neurobiology of learning and memory. Learn Mem. 2009;16:248–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.918309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. New York: Harper and Row; 1967. Depression: clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. The International Affective Picture System (IAPS) in the study of emotion and attention. In: Coan JA, Allen JJB, editors. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. New York: Cambridge UP; 2007. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Sabatinelli D, Lang PJ. Emotion and motivation II: sex differences in picture processing. Emotion. 2001;1:300–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Saxena S, Mandelkern MA, Fairbanks LA, Ho ML, Baxter LR. Brain metabolic changes associated with symptom factor improvement in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Gorski L, Belcher A, Huynh Q. The influence of sex versus sex-related traits on long-term memory for gist and detail from an emotional story. Conscious Cogn. 2004;13:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Gabrieli JD. Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10789–10794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162356599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretié L, Mercado F, Hinojosa JA, Martín-Loeches M, Sotillo M. Valence-related vigilance bias in anxiety studied through event-related potentials. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derakshan N, Eysenck MW. Effects of focus of attention on physiological, behavioural, and reported state anxiety in repressors, low-anxious, high-anxious, and defensive high-anxious individuals. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2001;14:285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, Denkova E. Neural correlates of encoding emotional memories: a review of functional neuroimaging evidence. Cell Sci Rev. 2008;5:78–122. [Google Scholar]

- Domes G, Schulze L, Böttger M, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Wirtz PH, Heinrichs M, Herpertz SC. The neural correlates of sex differences in emotional reactivity and emotion regulation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:758–769. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. Anxiety: the cognitive perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Johnson R., Jr Event-related potential (ERP) studies of memory encoding and retrieval: a selective review. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;51:6–28. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001001)51:1<6::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard MG, Kring AM. Sex differences in the time course of emotion. Emotion. 2007;7:429–437. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski TJ, Damasio H, Eichhorn GR, Tranel D. Effects of gender on blood flow correlates of naming concrete entities. Neuroimage. 2003;20:940–954. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber MJ, Otten LJ. Voluntary control over prestimulus activity related to encoding. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9793–9800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0915-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guderian S, Schott BH, Richardson-Klavehn A, Düzel E. Medial temporal theta state before an event predicts episodic encoding success in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5365–5370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900289106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Canli T. Individual differences in emotion processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig U, Abler B, Walter H, Erk S. Expecting unpleasant stimuli: an fMRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keselman HJ, Rogan JC. Repeated measures F tests and psychophysiological research: controlling the number of false positives. Psychophysiology. 1980;17:499–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Technical Report A-8. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 1997. International affective picture system (IAPS): affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Emotion, motivation, and anxiety: brain mechanisms and psychophysiology. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1248–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz KL, Sarinopoulos I, Cleven KL, Nitschke JB. The effect of anticipation and the specificity of sex differences for amygdala and hippocampus function in emotional memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14200–14205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601648103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak AK, Hu ZG, Zhang JX, Xiao Z, Lee TM. Sex-related differences in neural activity during emotion regulation. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2900–2908. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers Indiv Differ. 2004;37:1401–1415. [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Memory and anxiety disorders. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1755–1759. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Ochsner KN, Mauss IB, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ. Gender differences in emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Process Intergr Relat. 2008;11:143–162. doi: 10.1177/1368430207088035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP, Dixon C, Fisher S, Twelftree H, McWilliams A. Trait anxiety, defensiveness and selective processing of threat: an investigation using two measures of attentional bias. Pers Individ Diff. 2000;28:1063–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB, Sarinopoulos I, Mackiewicz KL, Schaefer HS, Davidson RJ. Functional neuroanatomy of aversion and its anticipation. Neuroimage. 2006;29:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten LJ, Quayle AH, Akram S, Ditewig TA, Rugg MD. Brain activity before an event predicts later recollection. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:489–491. doi: 10.1038/nn1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten LJ, Quayle AH, Puvaneswaran B. Prestimulus subsequent memory effects for auditory and visual events. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:1212–1223. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller KA, Wagner AD. Observing the transformation of experience into memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01845-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piefke M, Weiss PH, Markowitsch HJ, Fink GR. Gender differences in the functional neuroanatomy of emotional episodic autobiographical memory. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;24:313–324. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Mark RE, Gilchrist J, Roberts RC. ERP repetition effects in indirect and direct tasks: effects of age and interitem lag. Psychophysiology. 1997;45:572–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanquist TF, Rohrbaugh JW, Syndulko K, Lindsley DB. Electrocortical signs of levels of processing: perceptual analysis and recognition memory. Psychophysiology. 1980;17:568–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1980.tb02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons A, Matthews SC, Stein MB, Paulus MP. Anticipation of emotionally aversive visual stimuli activates right insula. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2261–2265. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200410050-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons A, Strigo I, Matthews SC, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Anticipation of aversive visual stimuli is associated with increased insula activation in anxiety-prone subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;15:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Corwin J. Perceptual identification thresholds for 150 fragmented pictures from the Snodgrass and Vanderwart picture set. Percept Mot Skills. 1988;67:3–36. doi: 10.2466/pms.1988.67.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists; 1970. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Spreckelmeyer KN, Krach S, Kohls G, Rademacher L, Irmak A, Konrad K, Kircher T, Gründer G. Anticipation of monetary and social reward differently activates mesolimbic brain structures. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4:158–165. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Rossy LA, Ruiz-Padial E, Johnsen BH. Gender differences in the relationship between emotional regulation and depressive symptoms. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Memory and consciousness. Can Psychol. 1985;26:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vasey MW, Thayer JF. The continuing problem of false positives in repeated measures ANOVA in psychophysiology: a multivariate solution. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wais PE, Mickes L, Wixted JT. Remember/know judgments probe degrees of recollection. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:400–405. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Port JD, Abramowitz JS. A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2004;132:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The nature of recollection and familiarity: a review of 30 years of research. J Mem Lang. 2002;46:441–517. [Google Scholar]