Abstract

Infantile hemiplegia is one of the clinical forms of cerebral palsy that refers to impaired motor function of one half of the body owing to contralateral brain damage due to prenatal, perinatal and postnatal causes amongst which vascular lesion is the most common causative factor. We report here the effects of constraint-induced movement therapy in a five-year-old female child with infantile hemiplegia on improvement of upper extremity motor skills.

Keywords: Constraint-induced movement therapy, infantile hemiplegia, shaping

Introduction

The potential use of the affected upper extremity of children with hemiplegia often fails due to “learned non-use phenomenon”.[1] Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is one of the treatment strategies which utilizes the principles of neural plasticity to help acquire motor skills of the affected upper extremity.[2–7] This therapeutic approach involves constraining of the unaffected upper extremity using sling, plaster cast, mitt or splints and intensive training of the affected upper extremity with task-specific, goal-oriented activities by reinforcement (shaping technique).[8,9]

Case Report

A five-year-old female child presented with right hemiplegia with the history of delayed motor milestones and limited motor skills of the right upper extremity since birth. The history given by parents was suggestive of birth asphyxia. The objective details of the cause of hemiplegia could not be established as there were no medical records available. The child had no history of seizure or any other form of developmental delay. The child had not undergone any physical therapy interventions earlier. Presently, she has achieved the highest level of functional independence (able to walk and run independently). She displayed no voluntary effort to initiate any motor skills of the right upper extremity unless verbally prompted, even otherwise initiating only minimal response suggesting learned non-use phenomenon. The following criteria were considered for use of CIMT in this child (adapted from Cochrane review study).[10]

Observed learned non-use of affected upper extremity.

A possible movement of at least 10° extension at metacarpophalangeal and inter-phalangeal joints and 20° extension at wrist of the affected upper extremity.

No cognitive impairment and shall cooperate with treatment.

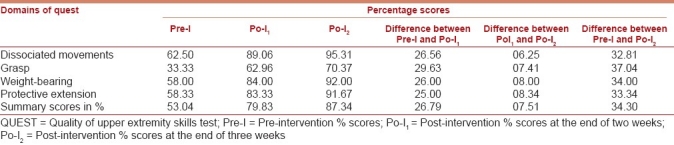

Outcome measure: Quality of upper extremity skills test

The Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test (QUEST) is a criterion-referenced measure that evaluates the quality of upper extremity function in four domains: dissociated movements (19 items with one level of response for each item), grasps (six items with three to five levels of response for each item), weight-bearing (five items with six levels of response for each item) and protective extension (three items with six levels of response for each item). It is designed to be used with children who exhibit neuromotor dysfunction with spasticity and has been validated with children 18 months to eight years of age. The data collected during the Neuro Developmental Therapy/Casting study by Law et al., were used to analyze the validity and responsiveness of the QUEST.[11]

Intervention procedure

The parents of the child were counseled for the treatment approach that could improve the motor skills of the affected right upper extremity. The parents were interested and were keen in subjecting their child to this treatment approach and gave informed consent. The pre-intervention assessments of the right upper extremity motor skills were measured using QUEST. The unaffected left upper extremity was constrained with posterior slab plaster cast extending above the elbow to the interphalangeal joints of fingers and supported with a sling. The parents were instructed to maintain the constraint for at least two weeks. The affected right upper extremity was then subjected to task-specific goal-oriented activities that aimed to improve reaching, grasps, manipulation and release of the object using the arm and hand. The activities were encouraged using play way method and reinforcements using visual (postural mirror) and verbal feedback. The therapy session usually lasted for one hour a day for five days a week. The parents were instructed to constantly encourage the same activities that were carried out during the treatment session in daily activities. At the end of the two-week period, post-intervention assessment of the right upper extremity was done using QUEST. As there was an incremental response in the outcome measure, the investigators convinced the parent to continue the treatment for another week. At the end of three weeks, once again post-intervention assessment was done.

Results

As the QUEST measure analyzes the quality of motor skills of both the right and left extremity, it may be noted that the pre-intervention percentage score was 53.04% indicating full percentage score of unaffected left upper extremity and marginal percentage score of affected right upper extremity [Table 1]. Following intervention, increments in percentage score by 26.79% and 07.51% were observed at the end of two weeks and three weeks respectively which should be attributed to the improvements in the quality of motor skills of the affected right upper extremity. It may also be noted that the grasp percentage score was greater than other domains indicating better improvement in fine motor skills than gross motor skills. The overall increment observed was 34.30%.

Table 1.

Summary of QUEST scores

Discussion

The main concern for the parents in the use of CIMT for improving the motor skills of the affected upper extremity in infantile hemiplegia was the fact that it restricts the use of the unaffected extremity. The success of the use of CIMT in infantile hemiplegia depends on the parents, their proper understanding of the concept of the approach and their deep motivation in carrying out home exercises. The increments in percentage scores observed in this case report are attributed to the increased demands for the use of the affected upper extremity while constraining the unaffected upper extremity through task-specific goal-oriented activities that were reinforced with visual and verbal feedback.

Conclusion

The observation of this case report indicates that the use of CIMT could reverse the learned non-use phenomenon of the affected upper extremity in infantile hemiplegia and thus reduce disability to greater extent.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Taub E, Uswatte G, Mark VW, Morris DM. The learned nonuse phenomenon: Implications for rehabilitation. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:241–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taub E, Ramey SL, DeLuca S, Echols K. Efficacy of constraint induced movement therapy for children with cerebral palsy with asymmetric motor impairment. Pediatrics. 2004;113:305–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-sundholm L, Shaw K, Wang C. Effects of constraint induced movement therapy in young children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: An adapted model. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:266–75. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liepert J, Bauder H, Wolfgang HR, Miltner WH, Taub E, Weiller C. Treatment induced cortical reorganization after stroke in humans. Stroke. 2000;31:1210–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taub E, Uswatte G, Pidikiti R. Constraint-induced movement therapy: A new family of techniques with broad application to physical rehabilitation – A clinical review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1999;36:237–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis JK, Morello A, Davie A, Rice JC, Bennett JT. Forced use treatment of childhood hemiparesis. Pediatrics. 2002;110:94–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crocker MD, Mackay-Lyons M, McDonnell E. Forced use of the upper extremity in cerebral palsy: A single-case design. Am J Occup Ther. 1997;51:824–32. doi: 10.5014/ajot.51.10.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taub E, Crago JE, Burgio LD, Groomes TE, Cook EW, 3rd, DeLuca SC, et al. An operant approach to rehabilitation medicine: Overcoming learned nonuse by shaping. J Exp Anal Behav. 1994;61:281–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang HH, Fetters L, Hale J, McBride A. Bound for success: A systematic review of constraint-induced movement therapy in children with cerebral palsy supports improved arm and hand use. Phys Ther. 2009;89:1126–41. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirtori V, Corbetta D, Moja L, Gatti R. Constraint induced movement therapy for upper extremities in stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004433. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004433.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law M, Cadman D, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, DeMatteo C. Neurodevelopmental therapy and upper extremity inhibitive casting for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1991;33:379–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1991.tb14897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]