Abstract

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an inflammatory immune-mediated disorder which is more common in pediatric patients. The clinical setting is characterized by a rapid onset of encephalopathy and multifocal neurological features. Acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitis (AHEM) is considered a rare form of ADEM. This report shows a 2-year-old patient who presented with the classical features of ADEM and after 8 weeks developed severe neurological worsening. The second magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed hemorrhagic lesions. Differences in prognosis between ADEM and AHEM justify the investigation of AHEM whenever a patient has neurological recrudescence in a known patient of ADEM.

Keywords: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, acute hemorrhagic, childhood

Introduction

In an attempt to develop a uniform classification of the most common demyelinating disorder of childhood, the International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group proposes the definition of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) as “the first clinical event with a polysymptomatic encephalopathy, with acute or subacute onset, showing focal or multifocal hyperintense lesions predominantly affecting the CNS white matter”. Beyond that, evidences of previous destructive white matter changes or clinical setting of a demyelinating event must not be present in the patient's history.[1] The risk of developing multiple sclerosis after ADEM has been focused by many studies in the literature.[1–3]

The clinical features of ADEM are well known among pediatric neurologists and the outcome usually shows complete recovery in up to 50%, even in those patients who are not treated.[1] Nevertheless, some forms of presentation have peculiarities and they might be a challenge. Acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitis (AHEM) is considered a rare form of ADEM's presentation due to acute brain vasculitis. Immediate and aggressive treatment is required because this clinical scenario shows high mortality.[1]

Herein, the authors report a case of AHEM with remarkable abnormalities of brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) who had an unfavorable outcome. Besides, a review of similar pediatric cases previously reported in the literature has been given.

Case Report

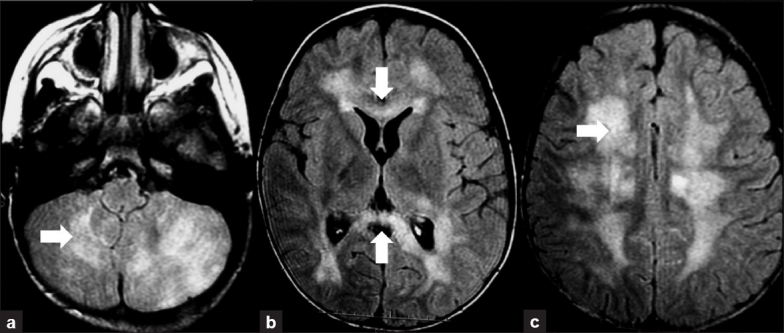

A 2-year-old, previously healthy girl was admitted to the hospital with a 1 week history of extreme irritability. Associated with irritability, her parents noticed progressive difficulty in walking. She did not have any antecedent history of infection or vaccination preceding the present symptoms. The neurological examination on the first evaluation showed impairment of consciousness, ranging from irritability to numbness. She was unable to walk without support due to cerebellar ataxia. Brisk deep tendon reflexes, bilateral Babinski sign and ankle clonus were present. Computed tomography scan was normal and the cerebrospinal fluid showed the following: white cell count 15 cells/mm3(92% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 3% neutrophils), red blood cells 15/mm3, protein levels 70 mg/dL, gamma globulin levels 18.3% on protein electrophoresis, and glucose levels 47 mg/dL. Acid-fast bacilli staining was negative as was polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex and cytomegalovirus. Fungal and bacterial cultures were negative. The first MRI showed hyperintense FLAIR/T2 lesions in cerebellar white matter [Figure 1a], and also in central, periventricular and juxtacortical white matter [Figure 1b and c].

Figure 1.

First Brain MRI. Axial FLAIR images demonstrating hyperintense extensive and confluent lesions in cerebellar white matter (a), affecting the corpus callosum (b) and compromising the central and juxtacortical white matter (c)

She had significant improvement after IV administration of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg/day) for 5 days, followed by oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day) taper for 6 weeks.

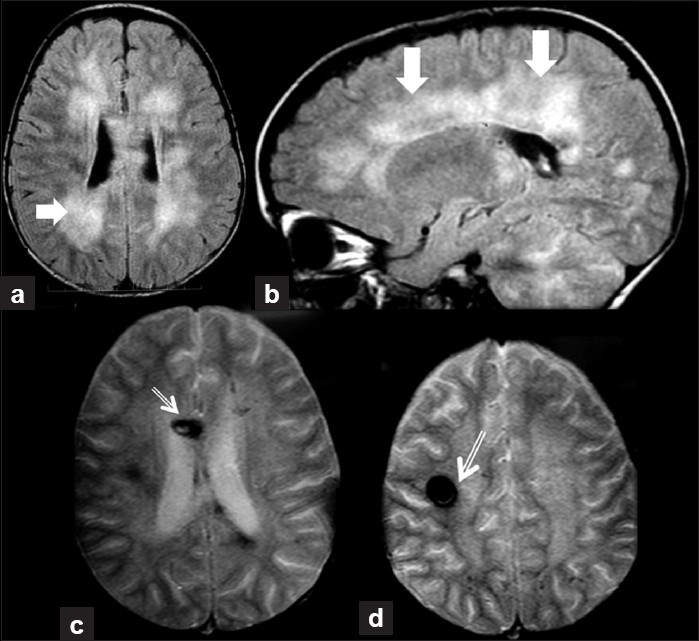

After 2 months of the initial symptoms, she had recurrence of her symptoms, associated with rapidly progressive refractory status epilepticus. An electroencephalogram obtained showed delta wave activity that was consistent with diffuse, severe encephalopathy. Continuous sharp waves on parasagittal and right temporal regions were observed in the records. It was necessary to administer IV midazolam (23 μg/kg/min) followed by thiopental (50 mg/kg/hour) to control the seizures. The second MRI, in addition to the impairment of cerebral and cerebellar white matter [Figure 2a and b], showed hemorrhagic lesions in the corpus callosum and right centrum semiovale [Figure 2c and d]. She was submitted to a new high-dose IV steroid therapy and IV immunoglobulin, but no improvement was observed and she died after a nosocomial pneumonia following 2 months of intubation.

Figure 2.

Second brain MRI. Axial FLAIR image (a) demonstrating hyperintense extensive and confluent lesions in central and juxtacortical white matter (dense arrow). Sagittal reformation (b) shows involvement of pericallosal and cerebellar white matter, sparing the U-fibers (dense arrows). Axial T2 gradient echo-weighted images (c and d) showing areas of very low signal, corresponding to breakdown products of hemoglobin (thin arrows), in the corpus callosum (c) and in the right centrum semiovale (d)

Discussion

Whereas ADEM is more commonly diagnosed in children, AHEM is seen most frequently among adults.[4,5] AHEM is usually fatal, whereas full recovery is the rule for patients with ADEM.[1,6]

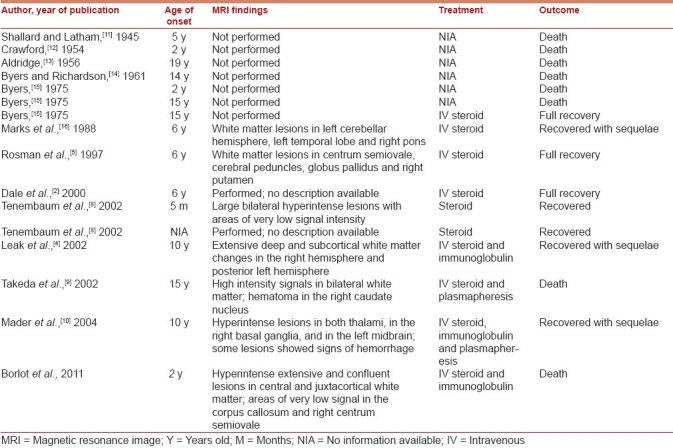

In 1997, Rosman et al. reported a pediatric case of AHEM with a good outcome, and they did a review of the cases published before,[5] since the first description by Hurst in 1941.[7] At that time, there were nine pediatric cases published with pathological or radiologic confirmation.[5] After 2000, the largest ADEM series in childhood have demonstrated only three cases of AHEM.[2,8] In Tenembaum and coworkers’ series, 2 of 84 patients showed some degree of hemorrhage into the large demyelinating lesions. One of the two patients with AHEM had complete recovery with normal neurological examination. One patient showed Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of 3.0–4.5.[8] Dale et al. have published 35 cases of ADEM, and only one scan had evidence of secondary hemorrhage.[2] Three additional cases were published as case reports by Leake,[4] Takeda,[9] and Mader in 2004.[10] The patients were 10, 15 and 10 years old, respectively.[4,9,10] Overall, 16 pediatric cases have been reported, including the one on this report [Table 1]. The mortality of these 16 cases was 50% (8/16). Among the eight survivors, clinical information was available in seven: four patients recovered with sequelae and three patients made a full recovery. Despite the severe presentation of most ADEM cases, the outcome of nonhemorrhagic forms usually is favorable in childhood, with full recovery to normal neurological state in more than 50–60% of patients, as previously demonstrated by the main series.[1,2,6,8]

Table 1.

Pediatric cases of acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitis

Because of the epidemiological data, and especially the outcome between ADEM and AHEM, some authors have tried to separate these conditions.[4,5,9,17] However, distinction between ADEM and AHEM is not well established and they may be a continuation of disease spectrum.[1,5,10,17] The case presented herein is in agreement with the concept that both disorders are considered as autoimmune-mediated entities, with pathological features of prominent multifocal perivascular demyelination. The patient had a typical presentation of ADEM with an initial good response to steroids, and in an unexpected way, she relapsed with recurrence of symptoms associated with refractory status epilepticus, and a new MRI disclosing hemorrhagic features. As the relapse took place within the first 3 months from the initial event, it was considered temporally related to the same acute monophasic condition,[1] but with subsequent vessel occlusion leading to a secondary hemorrhage.

Even though some authors have reported favorable neurologic outcome in adult patients, the high rate of AHEM mortality mandates a quick and aggressive treatment using combinations of corticosteroids, immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, and plasma exchange.[1,4,5,17–19]

The case reported here emphasizes that ADEM may present a severe outcome, making this well-known condition a challenge. AHEM must be properly investigated with MRI whenever a patient presents with unexpected neurological worsening. Aggressive therapeutic management is required in order to avoid fatal outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Tenembaum S, Chitnis T, Ness J, Hahn JS. International Pediatric MS Study Group. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology. 2007;68(16 Suppl 2):S23–36. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale RC, de Sousa C, Chong WK, Cox TC, Harding B, Neville BG. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis in children. Brain. 2000;123:2407–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikaeloff Y, Suissa S, Vallée L, Lubetzki C, Ponsot G, Confavreux C, et al. First episode of acute CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood: Prognostic factors for multiple sclerosis and disability. J Pediatr. 2004;144:246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leake JA, Billman GF, Nespeca MP, Duthie SE, Dory CE, Meltzer HS, et al. Pediatric acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis: Report of a surviving patient and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:699–703. doi: 10.1086/338718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosman NP, Gottlieb SM, Bernstein CA. Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis: Recovery and reversal of magnetic resonance imaging findings in a child. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:448–54. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anlar B, Basaran C, Kose G, Guven A, Haspolat S, Yakut A, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: Outcome and prognosis. Neuropediatrics. 2003;34:194–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurst EW. Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis: A previously undefined entity. Med J Aust. 1941;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tenembaum S, Chamoles N, Fejerman N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: A long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients. Neurology. 2002;59:1224–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda H, Isono M, Kobayashi H. Possible acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis manifesting as intracerebral hemorrhage on computed tomography. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2002;42:361–3. doi: 10.2176/nmc.42.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mader I, Wolff M, Niemann G, Küker W. Acute haemorrhagic encephalomyelitis (AHEM): MRI findings. Neuropediatrics. 2004;35:143–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shallard B, Latham O. A case of acute haemorrhagic leucoencephalitis. Med J Aust. 1945;1:145–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford T. Acute haemorrhagic leuco-encephalitis. J Clin Pathol. 1954;7:1–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldridge HE. Acute haemorrhagic leuco-encephalitis. Br Med J. 1956;6:807–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4996.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byers RK, Richardson EP., Jr Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: Case48-1961. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:34–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196107062650110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byers RK. Acute haemorrhagic leucoencephalitis: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1975;56:727–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks WA, Bodensteiner JB, Bobele GB, Hamza M, Wilson DA. Parainflammatory leukoencephalomyelitis: Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Child Neurol. 1988;3:205–13. doi: 10.1177/088307388800300311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein C, Wijdicks EF, Earnest F., 4th Full recovery after acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis(Hurst's disease) J Neurol. 2000;247:977–9. doi: 10.1007/s004150070060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan LJ, Bowman R, Zantek ND, Sherr G, Maxwell R, Clark HB, et al. Use of therapeutic plasma exchange in the management of acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis: A case report and review of the literature. Transfusion. 2007;47:981–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markus R, Brew BJ, Turner J, Pell M. Successful outcome with aggressive treatment of acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:551. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.4.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]