Abstract

Silibinin is a composition of the silymarin group as a hepatoprotective agent, and it exhibits various biological activities, including antibacterial activity. In this study, the antibacterial activities of silibinin were investigated in combination with two antimicrobial agents against oral bacteria. Silibinin was determined with MIC and MBC values ranging from 0.1 to 3.2 and 0.2 to 6.4 μg/mL, ampicillin from 0.125 to 64 and 0.5 to 64 μg/mL, gentamicin from 2 to 256 and 4 to 512 μg/mL, respectively. The ranges of MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.025–0.8 μg/mL and 0.1–3.2 μg/mL, respectively. The antibacterial activities of silibinin against oral bacteria were assessed using the checkerboard and time-kill methods to evaluate the synergistic effects of treatment with ampicillin or gentamicin. The results were evaluated showing that the combination effects of silibinin with antibiotics were synergistic (FIC index <0.5) against all tested oral bacteria. Furthermore, a time-kill study showed that the growth of the tested bacteria was completely attenuated after 2–6 h of treatment with the MBC of silibinin, regardless of whether it was administered alone or with ampicillin or gentamicin. These results suggest that silibinin combined with other antibiotics may be microbiologically beneficial and not antagonistic.

1. Introduction

Dental plaque is a film of microorganisms on the tooth surface that plays an important role in the development of caries and periodontal diseases [1–3]. Corrective treatment for such infectious diseases requires the reduction and/or elimination of bacterial accumulations in the retentive sites on the top of the teeth (occlusal surfaces) and between teeth by daily toothbrushing and frequent dental cleanings or prophylaxis [4, 5]. Several antibacterial agents including fluorides, phenol derivatives, ampicillin, erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline, and vancomycin have been used widely in dentistry to inhibit bacterial growth [6–8]. However, excessive use of these chemicals can result in derangements of the oral and intestinal flora and cause side effects such as microorganism susceptibility, vomiting, diarrhea, and tooth staining [9–11]. These problems necessitate further search for natural antibacterial agents that are safe for humans and specific for oral pathogens. Natural products have recently been investigated more thoroughly as promising agents to prevent oral diseases, especially plaque-related diseases such as dental caries [12–15].

Silymarin is a standardized extract obtained from the seeds of milk thistle (Silybum marianum), which contains approximately 70–80% of the silymarin flavonolignans [16–18]. Silibinin is a major bioactive component of silymarin flavonolignans [19, 20]. Both silymarin and silibinin have been used as traditional drugs for ≥2000 years to treat a range of liver disorders, including hepatitis and cirrhosis, and to protect the liver against poisoning from exposure to chemical and environmental toxins, including insect stings, mushroom poisoning, and alcohol [16, 20, 21]. Recently, in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that silibinin possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiarthritic activities, and it has chemopreventive efficacy on lung carcinoma, prostate cancer, breast carcinoma, hepatic disorder, and colon carcinoma [22–25]. In a previous study, silibinin showed antibacterial activity against the Gram-positive bacteria Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus epidermidis [26].

In this study, we investigated the synergistic antibacterial activity of silibinin in combination with the existing antimicrobial agents against oral bacteria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

The oral bacterial strains used in this study were Streptococcus mutans ATCC 25175, Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10556, Streptococcus sobrinus ATCC 27607, Streptococcus ratti KCTC (Korean collection for type cultures) 3294, Streptococcus criceti KCTC 3292, Streptococcus anginosus ATCC 31412, Streptococcus gordonii ATCC 10558, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 43717, Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 10953, Prevotella intermedia ATCC 25611, and Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277. Brain-heart infusion broth supplemented with 1% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich) was used for all bacterial strains except P. intermedia and P. gingivalis. For P. intermedia and P. gingivalis, brain-heart infusion broth containing hemin and menadione was used.

2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations/Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations Assay

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for silibinin by the broth dilution method [15] and were carried out in triplicate. The antibacterial activities were examined after incubation at 37°C for 18 h (facultative anaerobic bacteria), 24 h (microaerophilic bacteria), and 1-2 days (obligate anaerobic bacteria) under anaerobic conditions. MICs were determined as the lowest concentration of test samples that resulted in a complete inhibition of visible growth in the broth. Following anaerobic incubation of MICs plates, the minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined on the basis of the lowest concentration of silibinin that kills 99.9% of the test bacteria by plating out onto each appropriate agar plate. Ampicillin and gentamicin were used as standard antibiotics in order to compare the sensitivity of silibinin against test bacteria.

2.3. Checker-Board Dilution Test

The antibacterial effects of a combination of silibinin, which exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity, and antibiotics were assessed by the checkerboard test as previously described [15]. The antimicrobial combinations assayed included silibinin with ampicillin or gentamicin. Serial dilutions of two different antimicrobial agents were mixed in cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the MIC was determined to be the minimal concentration at which there was no visible growth. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) is the sum of the FICs of each of the drugs, which in turn is defined as the MIC of each drug when it is used in combination divided by the MIC of the drug when it is used alone. The interaction was defined as synergistic if the FIC index was less than or equal to 0.5, additive if the FIC index was greater than 0.5 and less than or equal to 1.0, indifferent if the FIC index was greater than 1.0 and less than or equal to 2.0, and antagonistic if the FIC index was greater than 2.0.

2.4. Time-Kill Curves

Bactericidal activities of the drugs under study were also evaluated using time-kill curves on oral bacteria. Tubes containing Mueller-Hinton supplemented to which antibiotics had been added at concentrations of the MIC50 were inoculated with a suspension of the test strain, giving a final bacterial count 5∼6 × 106 CFU/mL. The tubes were thereafter incubated at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber, and viable counts were performed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, and 24 h after addition of antimicrobial agents, on agar plates incubated for up to 48 h in anaerobic chamber at 37°C. Antibiotic carryover was minimized by washings by centrifugation and serial 10-fold dilution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.3. Colony counts were performed in duplicate, and means were taken. The solid media used for colony counts were brain-heart infusion (BHI) agar for streptococci and brain-heart infusion agar containing hemin and menadione for P. intermedia and P. gingivalis.

3. Results and Discussion

The antibacterial activities and synergistic effects of silibinin alone or with antibiotics were evaluated in oral bacteria. The antibacterial activities of the ATCC and KCTC strains of oral bacteria to silibinin, ampicillin, and gentamicin alone and in combination are presented in Table 1. The MICs/MBCs for silibinin were found to be either 0.1/0.2 or 3.2/6.4 μg/mL, for ampicillin either 0.125/0.5 or 64/64 μg/mL, and for gentamicin, either 2/4 or 256/512 μg/mL. Silibinin MIC50 and MIC90 values for oral cariogenic bacteria were 0.025–0.2 μg/mL and 0.1–0.8 μg/mL, respectively, while for periodontopathogenic bacteria these values were 0.1–0.4 μg/mL and 0.4–3.2 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of silibinin and antibiotics in oral bacteria.

| Samples | Silibinin (μg/mL) | Ampicillin | Gentamicin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50< | MIC90< | MIC/MBC | MIC/MBC (μg/mL) | ||

| S. mutans ATCC 251751 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.2/0.4 | 0.125/0.5 | 8/16 |

| S. sanguinis ATCC 10556 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4/0.4 | 0.5/1 | 64/64 |

| S. sobrinus ATCC 27607 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4/0.8 | 0.5/1 | 4/8 |

| S. ratti KCTC 32942 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8/0.8 | 0.5/1 | 16/32 |

| S. criceti KCTC 3292 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8/1.6 | 1/2 | 8/16 |

| S. anginosus ATCC 31412 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8/1.6 | 1/2 | 32/32 |

| S. gordonii ATCC 10558 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.5/1 | 32/32 |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 43717 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.6/3.2 | 64/64 | 4/8 |

| F. nucleatum ATCC 51190 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 3.2/6.4 | 2/4 | 2/4 |

| P. intermedia ATCC 49049 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.6/3.2 | 4/8 | 16/32 |

| P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4/0.8 | 0.5/1 | 256/512 |

1American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

2Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

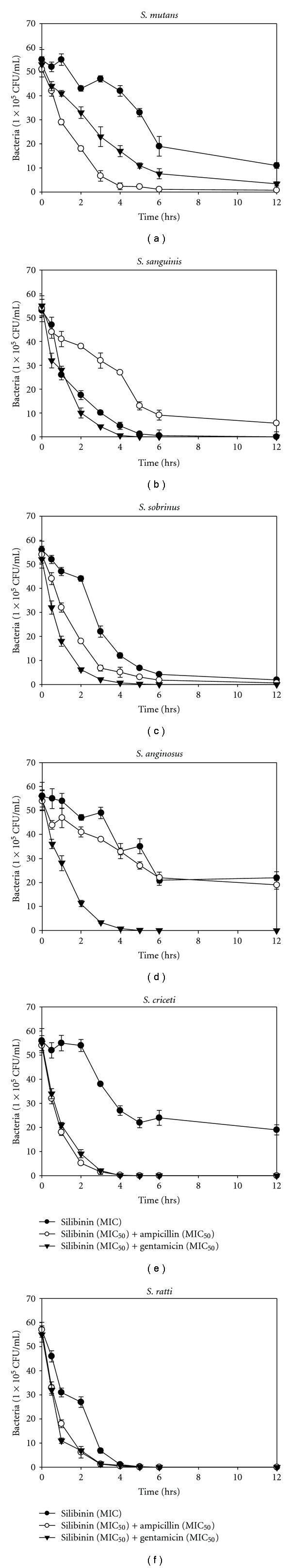

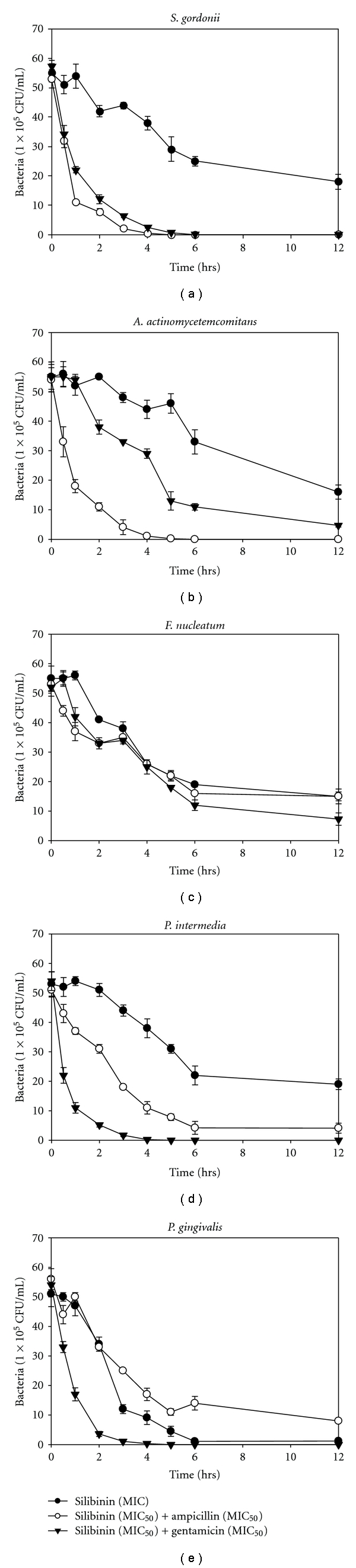

In combination with silibinin, the MIC for ampicillin was reduced to ≥4–8-fold in all tested bacteria, producing a synergistic effect as defined by FICI ≤ 0.5. The MBC for ampicillin has shown synergistic effects in all tested bacteria expect S. sanguinis, S. ratti, and P. intermedia (Table 2). In combination with silibinin, the MIC/MBC for gentamicin was reduced to ≥4–8-fold in all tested bacteria expect S. sanguinis and S. ratti by FICI ≥ 0.75 (Table 3). Many articles have revealed that Gram-positive bacteria was more sensitive to plant antimicrobials than Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that the results are due to the difference between the presence and absence of the outer membrane which can limit drug diffusion in harmony with multidrug transporters [15, 27–29]. In this study, silibinin also shows susceptibility on Gram-positive bacteria as well as Gram-negative bacteria. Many attempts have been made to eliminate S. mutans from the oral flora [30]. Antibiotics such as ampicillin, chlorhexidine, erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline, and vancomycin have been very effective in preventing dental caries [6, 31, 32]. Moreover, the antifungal activities have shown that neither silibinin nor silymarin II had antifungal activity against yeast [30]. The Gram-positive bacteria-specific properties of silibinin are caused by the inhibition of RNA and protein synthesis rather than by attacking the bacterial membrane [25, 26]. The bacterial effect of silibinin with ampicillin or gentamicin against oral bacteria was confirmed by time-kill curve experiments. The silibinin (MIC or MIC50) alone resulted in a rate of killing increasing or not changing in CFU/mL at time-dependent manner, with a more rapid rate of killing by silibinin (MIC50) with ampicillin (MIC50) or gentamicin (MIC50) (Figures 1 and 2). A strong bactericidal effect was exerted in drug combinations.

Table 2.

Synergistic effects of the silibinin with ampicillin against oral bacteria.

| Strains | Agent | MIC/MBC (μg/mL) | FIC | FICI2 | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | Combination1 | |||||

| S. mutans ATCC 251753 | Silibinin | 0.2/0.4 | 0.05/0.1 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 0.125/0.5 | 0.0312/0.125 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. sanguinis ATCC 10556 | Silibinin | 0.4/0.4 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.5/0.75 | Synergistic/additive |

| Ampicillin | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. sobrinus ATCC 27607 | Silibinin | 0.4/0.8 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. ratti KCTC 32944 | Silibinin | 0.8/0.8 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.375/0.75 | Synergistic/additive |

| Ampicillin | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.25/0.5 | |||

| S. criceti KCTC 3292 | Silibinin | 0.8/1.6 | 0.2/0.4 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.375 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 1/2 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.25/0.125 | |||

| S. anginosus ATCC 31412 | Silibinin | 0.8/1.6 | 0.2/0.4 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 1/2 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. gordonii ATCC 10558 | Silibinin | 0.1/0.2 | 0.025/0.05 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 43717 | Silibinin | 1.6/3.2 | 0.2/0.8 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 64/64 | 8/16 | 0.125/0.25 | |||

| F. nucleatum ATCC 51190 | Silibinin | 3.2/6.4 | 0.4/1.6 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.375/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 2/4 | 0.5/1 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| P. intermedia ATCC 49049 | Silibinin | 1.6/3.2 | 0.2/0.8 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.375/0.75 | Synergistic/additive |

| Ampicillin | 4/8 | 1/4 | 0.25/0.5 | |||

| P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 | Silibinin | 0.4/0.8 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Ampicillin | 0.5/1 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

1The MIC and MBC of the silibinin with ampicillin.

2The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FIC index).

3American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

4Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

Table 3.

Synergistic effects of the silibinin with gentamicin against oral bacteria.

| Strains | Agent | MIC/MBC (μg/mL) | FIC | FICI2 | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | Combination1 | |||||

| S. mutans ATCC 251753 | Silibinin | 0.2/0.4 | 0.05/0.1 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 8/16 | 2/4 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. sanguinis ATCC 10556 | Silibinin | 0.4/0.4 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.375/0.75 | Synergistic/additive |

| Gentamicin | 64/64 | 8/16 | 0.125/0.25 | |||

| S. sobrinus ATCC 27607 | Silibinin | 0.4/0.8 | 0.05/0.2 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.375/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 4/8 | 1/2 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| S. ratti KCTC 32944 | Silibinin | 0.8/0.8 | 0.2/0.4 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.5/0.625 | Synergistic/additive |

| Gentamicin | 16/32 | 4/4 | 0.25/0.125 | |||

| S. criceti KCTC 3292 | Silibinin | 0.8/1.6 | 0.2/0.4 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.375/0.375 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 8/16 | 1/2 | 0.125/0.125 | |||

| S. anginosus ATCC 31412 | Silibinin | 0.8/1.6 | 0.2/0.2 | 0.25/0.125 | 0.375/0.375 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 32/32 | 4/8 | 0.125/0.25 | |||

| S. gordonii ATCC 10558 | Silibinin | 0.1/0.2 | 0.025/0.05 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.375/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 32/32 | 4/8 | 0.125/0.25 | |||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 43717 | Silibinin | 1.6/3.2 | 0.4/0.8 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 4/8 | 1/2 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| F. nucleatum ATCC 51190 | Silibinin | 3.2/6.4 | 0.8/1.6 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.5 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 2/4 | 0.5/1 | 0.25/0.25 | |||

| P. intermedia ATCC 25611 | Silibinin | 1.6/3.2 | 0.4/0.8 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.5/0.375 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 16/32 | 4/4 | 0.25/0.125 | |||

| P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 | Silibinin | 0.8/0.8 | 0.1/0.2 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.375/0.375 | Synergistic/synergistic |

| Gentamicin | 256/512 | 64/64 | 0.25/0.125 | |||

1The MIC and MBC of the silibinin with gentamicin.

2The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FIC index).

3American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

4Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

Figure 1.

Time-kill curves of MIC of silibinin alone and its combination with MIC50 of ampicillin or gentamicin against S. mutans, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, S. anginosus, S. criceti, and S. ratti. Bacteria were incubated with silibinin (•), silibinin + ampicillin (∘), and silibinin + gentamicin (▾) over time. Data points are the mean values ± S.E.M. of six experiments. CFU: colony-forming units.

Figure 2.

Time-kill curves of MIC of silibinin alone and its combination with MIC50 of Amp or Gen against S. gordonii, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and P. gingivalis. Bacteria were incubated with silibinin (•), silibinin + Amp (∘), and silibinin + Gen (▾) over time. Data points are the mean values ± S.E.M. of six experiments. CFU: colony-forming units.

4. Conclusion

These findings suggest that silibinin fulfills the conditions required of a novel cariogenic bacteria and periodontal pathogens, particularly bacteroides species, drug and may be useful in the future in the treatment of oral bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported in part by research funds of Sun Moon University and and National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2008-331-E00348). There is no conflict of interests related to this research.

References

- 1.Grössner-Schreiber B, Fetter T, Hedderich J, Kocher T, Schreiber S, Jepsen S. Prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2006;33(7):478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekstrand KR, Bruun G, Bruun M. Plaque and gingival status as indicators for caries progression on approximal surfaces. Caries Research. 1998;32(1):41–45. doi: 10.1159/000016428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh PD, Bradshaw DJ. Dental plaque as a biofilm. Journal of Industrial Microbiology. 1995;15(3):169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01569822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White DJ, McClanahan SF, Lanzalaco AC, et al. The comparative efficacy of two commercial tartar control dentifrices in preventing calculus development and facilitating easier dental cleanings. Journal of Clinical Dentistry. 1996;7(2):58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen DH, Martin JT. Common dental infections in the primary care setting. American Family Physician. 2008;77(6):797–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allaker RP, Douglas CWI. Novel anti-microbial therapies for dental plaque-related diseases. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2009;33(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramamurthy NS, Schroeder KL, McNamara TF, et al. Root-surface caries in rats and humans: inhibition by a non-antimicrobial property of tetracyclines. Advances in Dental Research. 1998;12(2):43–50. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120011801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wara-aswapati N, Krongnawakul D, Jiraviboon D, Adulyanon S, Karimbux N, Pitiphat W. The effect of a new toothpaste containing potassium nitrate and triclosan on gingival health, plaque formation and dentine hypersensitivity. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32(1):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feres M, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Stewart B, De Vizio W. The effectiveness of a preprocedural mouthrinse containing cetylpyridiniuir chloride in reducing bacteria in the dental office. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2010;141(4):415–422. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pigrau C, Almirante B. Oxazolidinones, glycopeptides and cyclic lipopeptides. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2009;27(4):236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Strydonck DAC, Timmerman MF, Van Der Velden U, Van Der Weijden GA. Plaque inhibition of two commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32(3):305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saarni U, Saarni H. Xylitol for messrooms–a method worth trying to prevent caries among seafarers. Bulletin of the Institute of Maritime and Tropical Medicine in Gdynia. 1997;48(1–4):91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto H, Ogawa T. Antimicrobial activity of perilla seed polyphenols against oral pathogenic bacteria. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2002;66(4):921–924. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mu J. Anti-cariogenicity of maceration extract of Momordica grosvenori: laboratory study. Chinese Journal of Stomatology. 1998;33(3):183–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha JD, Jeong MR, Jeong SI, Lee KY. Antibacterial activity of sophoraflavanone G isolated from the roots of Sophora flavescens. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;17(5):858–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polyak SJ, Morishima C, Lohmann V, et al. Identification of hepatoprotective flavonolignans from silymarin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(13):5995–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kren V, Walterová D. Silybin and silymarin-new effects and applications. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacký, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2005;149(1):29–41. doi: 10.5507/bp.2005.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mereish KA, Bunner DL, Ragland DR, Creasia DA. Protection against microcystin-LR-induced hepatotoxicity by silymarin: biochemistry, histopathology, and lethality. Pharmaceutical Research. 1991;8(2):273–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1015868809990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sangeetha N, Felix AJW, Nalini N. Silibinin modulates biotransforming microbial enzymes and prevents 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced preneoplastic changes in experimental colon cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2009;18(5):385–394. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832d1b4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gažák R, Walterová D, Křen V. Silybin and silymarin-new and emerging applications in medicine. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;14(3):315–338. doi: 10.2174/092986707779941159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon A, Hobbs DA, Bowden DS, et al. Effects of Silybum marianum on serum hepatitis C virus RNA, alanine aminotransferase levels and well-being in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;21(1):275–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung CW, Gibbons N, Johnson DW, Nicol DL. Silibinin-a promising new treatment for cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;10(3):186–195. doi: 10.2174/1871520611009030186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazak R, Purchartova K, Marhol P, et al. Antioxidant and antiviral activities of silybin fatty acid conjugates. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;45(3):1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gazak R, Sedmera P, Vrbacky M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of silybin and 2,3-dehydrosilybin antiradical activity-role of individual hydroxyl groups. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;46(6):745–758. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Momeny M, Khorramizadeh MR, Ghaffari SH, et al. Effects of silibinin on cell growth and invasive properties of a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, HepG-2, through inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;591(1–3):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong GL, Hyung KK, Park Y, et al. Gram-positive bacteria specific properties of silybin derived from Silybum marianum. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2003;26(8):597–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02976707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha JD, Jeong MR, Jeong SI, et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Artemisia scoparia and A. capillaris. Planta Medica. 2005;71(2):186–190. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung KJ, Cha JD, Lee SH, et al. Involvement of staphylococcal protein A and cytoskeletal actin in Staphylococcus aureus invasion of cultured human oral epithelial cells. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2001;50(1):35–41. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim KJ, Yu HH, Cha JD, Seo SJ, Choi NY, You YO. Antibacterial activity of Curcuma longa L. against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytotherapy Research. 2005;19(7):599–604. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mäser P, Vogel D, Schmid C, Räz B, Kaminsky R. Identification and characterization of trypanocides by functional expression of an adenosine transporter from Trypanosoma brucei in yeast. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2001;79(2):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s001090000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Poi R. Chlorhexidine as an anticaries agent. Australian Dental Journal. 2001;46(1):p. 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanova EN. Comparative efficacy of local anticarious agents. Stomatologiya. 1990;69(2):60–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]