Abstract

Objective:

Perceived descriptive drinking norms often differ from actual norms and are positively related to personal consumption. However, it is not clear how normative perceptions vary with specificity of the reference group. Are drinking norms more accurate and more closely related to drinking behavior as reference group specificity increases? Do these relationships vary as a function of participant demographics? The present study examined the relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking behavior by ethnicity (Asian or White), sex, and fraternity/sorority status.

Method:

Participants were 2,699 (58% female) White (75%) or Asian (25%) undergraduates from two universities who reported their own alcohol use and perceived descriptive norms for eight reference groups: "typical student"; same sex, ethnicity, or fraternity/sorority status; and all combinations of these three factors.

Results:

Participants generally reported the highest perceived norms for the most distal reference group (typical student), with perceptions becoming more accurate as individuals' similarity to the reference group increased. Despite increased accuracy, participants perceived that all reference groups drank more than was actually the case. Across specific subgroups (fraternity/sorority members and men) different patterns emerged. Fraternity/sorority members reliably reported higher estimates of drinking for reference groups that included fraternity/ sorority status, and, to a lesser extent, men reported higher estimates for reference groups that included men.

Conclusions:

The results suggest that interventions targeting normative misperceptions may need to provide feedback based on participant demography or group membership. Although reference group-specific feedback may be important for some subgroups, typical student feedback provides the largest normative discrepancy for the majority of students.

Considerable research indicates that individuals tend to overestimate the drinking quantity and frequency of others, and this overestimation in turn is related to individuals' own drinking (Baer et al., 1991; Borsari and Carey, 2003; Larimer et al., 2004; Lewis and Neighbors, 2004). Perceptions of peers' drinking behavior are more strongly related to drinking than are parental attitudes, family history of alcohol problems, drinking motives, or alcohol outcome expectancies (Neighbors et al., 2007; Perkins, 2002). A variety of interventions focus on reducing overestimations of drinking norms, and research has generally supported efficacy of interventions using personalized normative feedback (i.e., provision of accurate information contrasting perceived and actual descriptive drinking norms with participant's own drinking behavior) as an efficacious college drinking intervention, alone or in combination with other prevention components (Carey et al., 2007; Larimer and Cronce, 2007; Walters and Neighbors, 2005). Furthermore, reductions in perceived descriptive norms have been shown to mediate efficacy of these interventions (Borsari and Carey, 2000; LaBrie et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2007).

Research suggests that the degree of overestimation varies by the specificity of the normative referent, and perceived drinking norms for more specific referent groups are uniquely associated with alcohol consumption (Larimer et al., 2009; Lewis and Neighbors, 2004; Lewis et al., 2007). Questions remain, however, regarding the extent to which normative perceptions vary based on specificity of the reference group (i.e., a more global reference to the "typical" student versus a reference to a more specific referent) and the extent to which perceived drinking norms for more specific reference groups differ from individual drinking behavior. Thus, it would be helpful to know whether students perceive differences in the prevalence of drinking of "typical students," versus male/female students, versus male/female fraternity/sorority students, versus White male/female fraternity/sorority students.

Similarly, it would be helpful to know whether students are more accurate in estimating the drinking prevalence of peers who are more similar to themselves and whether the relationship between their own drinking and normative perceptions based on more specific and similar reference groups is related to participants' own demographic characteristics. These are not minor issues, given the diversity of college student populations and emerging data suggesting that the efficacy of normative feedback interventions is moderated both by student characteristics and identification with normative reference groups (Lewis and Neighbors, 2007; Neighbors et al., 2010b).

The current research was designed to address these gaps in the literature to provide a basis for strengthening normative feedback interventions. Specifically, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the variability and accuracy of perceived norms for reference groups at increasing levels of specificity and similarity to the respondent and to evaluate differences between perceived norms for different reference groups and personal behavior as a function of participants' own gender, fraternity/sorority affiliation status, and ethnicity (Asian or White).

Specificity of the normative referent group

Although there is now consensus that perceived norms are important and an appropriate target for interventions, there remains an open question with respect to which normative referents matter most and for whom. Specifically, although several social psychological theories support the importance of proximal reference groups as more relevant and thus having greater potential to influence an individual's behavior (e.g., Festinger, 1954; Latané, 1981; Tajfel, 1982; Turner et al., 1987), alcohol research commonly has focused on perceived norms for the typical student (i.e., "college students in general" or "a typical student at your school"; Borsari and Carey, 2003). The quality of peer relationships in terms of level of intimacy, stability, and perceived support appears to be important in determining the magnitude and direction of peer influences on drinking (Borsari and Carey, 2006). Recent studies found that greater identification with a given group moderates associations between perceived drinking norms for that group and one's own drinking (Neighbors et al., 2010a; Reed et al., 2007).

Moreover, interventions have targeted group-specific normative misperceptions, including gender-specific norms (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004, 2007; Lewis et al., 2007; Thombs et al., 2005), freshman-specific norms (Lewis et al., 2007), and fraternity/sorority–specific norms (LaBrie et al., 2008). These efforts demonstrated that group-specific perceptions influence individuals' behavior, and thus, targeting these norms can assist in reducing drinking. For example, among intercollegiate athletes, perceived norms of a school-and gender-specific athletic peer reference group explained 69% of the variance in drinking (Hummer et al., 2009). After receiving group-specific normative feedback, athletes reduced their normative perceptions and drinking to more closely align with actual group norms (LaBrie et al., 2009). Therefore, research is emerging to suggest that, at least for certain groups of students, greater specificity of the normative reference group is important in understanding and using the influence of normative perceptions and misperceptions to reduce drinking.

Recently, Larimer et al. (2009) explored questions regarding the specificity of the normative reference group with respect to three dimensions of specificity: gender, ethnicity, and residence type (i.e., fraternity/sorority system housing, residence halls). Results indicated that college students did distinguish among the three different reference groups in estimating perceived descriptive norms (i.e., they overestimated the drinking among the three levels of specificity compared with both their own behavior and the mean of each specific group). Additionally, perceived norms for more specific groups (i.e., at two or three levels of specificity, such as gender–ethnicity specific) were uniquely related to participants' own drinking. Thus, these three levels of specificity may have particular salience for individuals in the assessment of perceived norms and interventions targeting these misperceptions. However, this research did not take the next step in determining whether these findings were similar for everyone or depended on students' own demographic status (i.e., gender, fraternity/sorority status, or ethnicity). Thus, the current study extends prior work in this area.

Gender specificity.

Male college students drink more frequently and with heavier drinking episodes relative to female students (Johnston et al., 2008; McCabe, 2002; O'Malley and Johnston, 2002). Research suggests that perceptions of normative drinking function differently for men and for women (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004, 2006; Suls and Green, 2003), and presentation of gender-specific feedback has been shown to be an effective intervention technique, particularly for female students with strong identity with their gender (Lewis and Neighbors, 2007). Gender specificity may be particularly relevant for women, given that female norms are lower than male norms or typical student norms. In addition, men and women tend to both view the typical student as male (Lewis and Neighbors, 2006). This fact suggests that perceptions of typical student drinking may be more similar to perceptions of male drinking than of female drinking.

Ethnicity/race specificity.

White and Hispanic college students report heavier drinking and more alcohol consequences than African American and Asian students (Office of Applied Studies, 2008; Paschall et al., 2005; Wechsler et al., 2000). Despite lower prevalence rates on average, Asian students are a group of particular interest and may be disproportionately understudied in clinical alcohol-related research among college students. There is wide variability in drinking behavior between Asian and White students, and there are large individual differences within Asian populations (Lum et al., 2009; Office of Applied Studies, 2008).

Furthermore, the stereotype that Asian students are not at risk for heavy episodic drinking and related consequences is inaccurate. Wechsler and colleagues (1998) found that nearly a quarter of Asian college students reported heavy episodic drinking at least once in the past 2 weeks, and Asian students experienced the greatest increase in prevalence of heavy episodic drinking from 1993 to 1997 of any student group (Wechsler et al., 1998, 2002). In addition, Asian American young adults have experienced significant increases in rates of alcohol abuse and dependence in recent years (Grant et al., 2004). Given that Asian Americans are among the fastest-growing ethnic minority groups in the United States (Barnes and Bennett, 2002), increased rates of heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders in this population are cause for concern.

Relatively little is known about how ethnicity/race–specific normative perceptions of alcohol use are related to actual drinking behavior for ethnic minority populations in general and for Asian college students in particular. Caetano and Clark (1999) found that Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics with more "liberal" attitudes and greater perceived approval of drinking behavior were more likely to be heavy drinkers than those with more "conservative" attitudes and lower perceived approval of drinking behavior. Similarly, Larimer et al. (2009) found that perceived norms for same-ethnicity referents were closer to one's own drinking than were typical student norms. However, Larimer and colleagues were unable to evaluate the extent to which this finding was moderated by ethnic minority or majority status; they also were unable to evaluate normative perceptions for specific ethnic groups. The present study thus extends prior research in important ways by adding to the literature on the role of drinking norms in Asian American college student populations in particular.

Fraternity/sorority status specificity.

Members of fraternities and sororities drink more heavily and more frequently than other students and report higher levels of alcohol-related consequences than students who are not involved in fraternities or sororities (Cashin et al., 1998; Larimer et al., 2004; Park et al., 2008; Sher et al., 2001). Research has shown that fraternity membership is a strong predictor of frequency of heavy drinking (Wechsler et al., 1995) for both alcohol-experienced and alcohol-naive beginning college students (Lo and Globetti, 1995). Overestimations of fraternity/sorority–specific drinking have been documented and have been shown to associate with individual drinking rates (Bartholow et al., 2003; Larimer et al., 1997, 2004), and correction of fraternity/sorority–specific perceived norms have mediated reductions in drinking during intervention (LaBrie et al., 2008).

Interestingly, although fraternity/sorority–affiliated students may overestimate the drinking of other fraternity/ sorority members, they may correctly estimate their drinking to be heavier than that of typical students (Larimer et al., 1997). Thus, fraternity/sorority–affiliated students may dismiss the normative information presented on typical students in traditional social norms approaches because they identify with other fraternity- and sorority-affiliated students, and "typical students" may not be a relevant or important reference group from their perspective. Further examinations of the accuracy of normative perceptions among fraternity/sorority–affiliated students and of how fraternity/sorority–specific perceptions are influential in predicting drinking behavior are needed.

Summary and hypotheses

Although findings of Larimer et al. (2009) suggest that the specificity of normative referents—in particular for gender, ethnicity, and residence type—is uniquely predictive of one's own drinking, additional research is needed to more fully understand the relationship of normative specificity to drinking behavior of diverse groups of students. Specifically, the Larimer et al. (2009) study was not sufficiently powered to conduct analyses of moderators of these effects. The current study extends these findings by increasing the sample size, focusing specifically on Asian and White students to better understand the impact of ethnicity on the relationship between perceived norms and drinking and to include sufficient samples of fraternity/sorority–affiliated and non-fraternity/sorority–affiliated students to evaluate differential patterns of relationship between norms and behavior among these different subsets of the population.

In the current study, we assessed self-reported drinking and perceived descriptive drinking norms for students at increasing levels of similarity to the respondents, based on a generic referent (typical student), as well as similarity at one level (sex, ethnicity, or fraternity/sorority affiliation), two levels (sex and ethnicity, sex and fraternity/sorority affiliation, or ethnicity and fraternity/sorority affiliation), and all three levels (perceptions of students who match the respondent on sex, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority affiliation). We hypothesized that students' estimates of drinking behavior would vary by the level of specificity of the normative referent group and that estimates would generally decrease as the level of specificity increased.

Furthermore, we expected that all estimates would be higher than the actual reported drinking behavior of the sample. In relation to relevant demographics (i.e., fraternity/ sorority affiliation, sex, and ethnicity), we expected that estimates for normative referent groups in which fraternity/sorority affiliation was included would be higher than estimates for when fraternity/sorority affiliation was not included. We hypothesized that estimates for normative referent groups in which sex was included would be higher for male normative referents than for female normative referents (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004) and that estimates for normative referents including ethnicity would be higher for White referents than for Asian referents. Finally, we aimed to examine the extent to which the accuracy of normative perceptions for more general versus more specific reference groups would vary among fraternity/sorority affiliation, sex, and ethnic (Asian versus White) subgroups.

Method

Participants and recruitment

Participants were undergraduate students who self-identified as White or Asian, recruited from two West-Coast campuses during the fall of 2007. Campus 1 (n = 1,607) is a large, public research university with an undergraduate enrollment of more than 27,000 students. Campus 2 (n = 1,091) is a private mid-size university with approximately 6,000 undergraduate students. A random sample of 7,000 registered students (3,500 from each campus) received letters and emails describing the study and containing a link to participate, along with a unique participant identification number. Once students clicked on the link and entered their participant identification number, an institutional review board-approved informed consent screen appeared. After providing consent, participants were routed to a 25-minute survey, for which they received $20. All measures and procedures were reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board on both campuses.

Of 3,753 respondents (54% response rate; n1 = 1,936; n2 = 1,817), 2,699 (58% female) self-identified as Asian or White and were included in the present analyses. Participants' ages ranged from 18 to 25 years (M = 19.8, SD = 1.4), with 96% of students ages 18–22 years. Seventy-five percent of participants self-identified as White (n = 2,012), whereas 25% self-identified as Asian (n = 687). Of the 3,248 students who did not respond (47.8% female), 56.5% were White (n = 1,835) and 19.3% were Asian (n = 627). Thus, responders somewhat overrepresented women and Asian students relative to the campus populations.

Combining both campuses, the participants reported consuming an average of 6.4 (SD = 8.9) drinks per week (MCampus 1 = 5.2, SD = 8.3, drinks per week; MCampus 2 = 8.0, SD = 9.6, drinks per week). A total of 32.5% of the students described themselves as nondrinkers (Campus 1 = 37.4%; Campus 2 = 27.3%). The students who identified themselves as drinkers (67.5%) reported an average of 8.9 (SD = 9.1) drinks per week, with a mean frequency of 2.4 (SD = 1.3) drinking occasions per week (MCampus 1 = 8.2 drinks per week, SD = 9.0, on MCampus 1 = 2.3, SD = 1.3, drinking days per week; MCampus 2 = 9.7, SD = 9.2, drinks per week on MCampus 2 = 2.4, SD = 1.3, drinking days per week).

Measures

In addition to demographic information (age, gender, ethnic/racial identification, type of residence, and fraternity/sorority membership), measures in the survey relevant to the current study included items assessing alcohol use and perceived descriptive norms for alcohol use.

Alcohol consumption.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985; Kivlahan et al., 1990) assessed average drinking on each day of a typical week, estimated over the past month. The participants were provided with information regarding a standard drink for use in all measures of alcohol consumption and perceived descriptive norms. Specifically, a drink was defined as a beverage that contained approximately one half ounce of ethyl alcohol (with examples provided ranging from 12 oz. of beerto 1 measured shot of distilled spirits).

Perceived descriptive norms.

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer et al., 1991) parallels the Daily Drinking Questionnaire and assesses the participants' perceptions of their peers' drinking habits. The participants provided an estimated number of drinks consumed by the typical student in each of their eight reference groups (described below) for each day of the week, resulting in 56 estimations.

Reference groups.

Participants answered Drinking Norms Rating Form items for eight reference groups. Reference groups were operationalized at four levels of specificity, involving estimations for reference groups of increasing similarity to the respondent based on gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority membership. Thus, the first level of specificity was the typical student on a given campus. The second level referred to the typical student similar to the respondent on a single level across these dimensions (e.g., "typical male student"; "typical Asian student"; "typical student in a fraternity or sorority"). The third level involved all combinations of two types of specificity (e.g., "typical male Asian student"). The final level involved estimation of drinking behavior for the typical student matching the respondent on all three levels of specificity (e.g., "typical female Asian, non–fraternity/sorority–affiliated student").

Results

Descriptive analyses

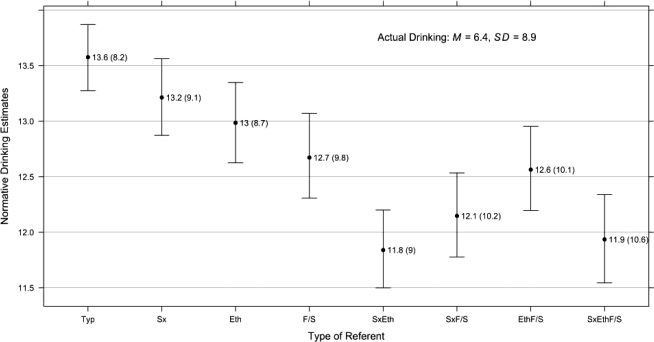

The participants' normative estimates of drinking across a variety of referents are shown in Figure 1. Mean normative drinking estimates for the typical student are highest, and, as the reference group becomes more similar, estimates generally decrease, although this pattern is not as clear when several reference groups are combined (e.g., students with similar ethnicity and fraternity/sorority status). Moreover, all estimates are far above the mean of students' actual reported weekly drinking, by approximately a factor of two.

Figure 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for normative drinking across eight reference groups. Means and standard deviations are reported adjacent to plotted data. Acronyms for reference groups: Typ = typical; Sx = same gender; Eth = same ethnicity; F/S = same fraternity/sorority status; SxEth = same gender and ethnicity; SxF/S = same gender and fraternity/sorority status; EthF/S = same ethnicity and fraternity/sorority status; SxEthF/S = same gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status.

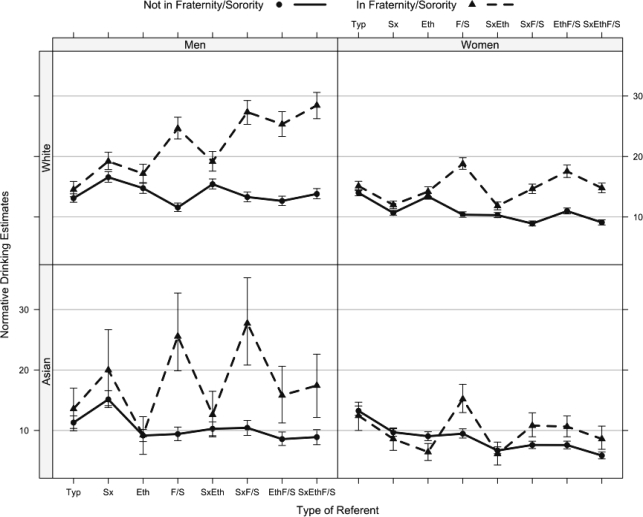

Figure 2 presents means and 95% confidence intervals for normative drinking estimates, with data presented by gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status of the respondent. The figure reveals that the overall downward trend in normative drinking estimates by more specific referents does not hold for all subgroups. In particular, the downward trend with increasing specificity is primarily driven by students who are not affiliated with a fraternity or sorority, regardless of ethnicity or gender (solid black lines in all four panels), although it is somewhat more notable among women (solid black lines in right two panels).

Figure 2.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for normative drinking across eight reference groups, separately for subgroups of gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status. Means and standard deviations are reported adjacent to plotted data. Acronyms for reference groups: Typ = typical; Sx = same gender; Eth = same ethnicity; F/S = same fraternity/sorority status; SxEth = same gender and ethnicity; SxF/S = same gender and fraternity/sorority status; EthF/S = same ethnicity and fraternity/sorority status; SxEthF/S = same gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status.

There also appear to be interactions (tested below) between demographic characteristics of the participants and specific referent groups. This is most obvious with fraternity/ sorority students (dotted lines in each panel), who show reliably higher drinking estimates for referent groups with fraternity/sorority identities. To a lesser degree, a similar pattern appears with gender (i.e., men in left panels reliably show higher estimates and women in right panels show lower estimates when gender is part of the referent) and with ethnicity (i.e., White students in upper panels show reliably higher estimates for students of the same ethnicity relative to Asian students in lower panels). The variability in confidence intervals is strongly related to sample sizes for the various subgroups (e.g., there were only 21 Asian men in fraternities and 25 Asian women in sororities).

Multilevel model of descriptive norms

A multilevel model was fit to the descriptive norms data that directly maps onto the data presented in Figure 2. Specifically, log-transformed estimates of drinking were the dependent variable, and dummy-coded predictors included the type of referent (seven contrasts compared with the typical student), gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status. A random intercept term accounted for the correlation because of eight drinking estimates for each student. Given the patterns shown in Figure 2, we included all main effects, two-way interactions, and three-way interactions. The resulting model is quite complex, including 56 separate fixed effects, although these effects are estimated from a total of 21,148 data points. Given that the present focus is on broader patterns of drinking across referents and demographic characteristics, omnibus F tests are used, as opposed to presenting all 56 individuals' fixed effects (although tables with these effects are available from the first author).

As seen in Table 1, all main effects are significant, as are all two-way and three-way interactions involving the type of referent. These results broadly confirm what is seen in Figure 2, that drinking estimates at different levels of specificity vary by demographic subgroups. For example, the Reference × Fraternity/Sorority × Gender interaction reflects that fraternity/sorority members make higher drinking estimates when fraternity/sorority affiliation is part of the referent but that men increase their estimates by a greater amount.

Table 1.

Hierarchical linear modeling results of descriptive norms predicted from type of referent, gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status

| Variable | df | F | P |

| Intercept | 1 | 39,898.7 | <.01 |

| Reference | 7 | 172.4 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/sorority | 1 | 221.3 | <.01 |

| Gender | 1 | 52.8 | <.01 |

| Ethnicity | 1 | 154.7 | <.01 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority | 7 | 303.3 | <.01 |

| Reference × Gender | 7 | 203.4 | <.01 |

| Reference × Ethnicity | 7 | 133.1 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Gender | 1 | 8.0 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Ethnicity | 1 | 0.2 | .68 |

| Gender × Ethnicity | 1 | 0.3 | .57 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority × Gender | 7 | 9.5 | <.01 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority × Ethnicity | 7 | 3.5 | <.01 |

| Reference × Gender × Ethnicity | 7 | 2.4 | <.02 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Gender × Ethnicity | 1 | 0.3 | .56 |

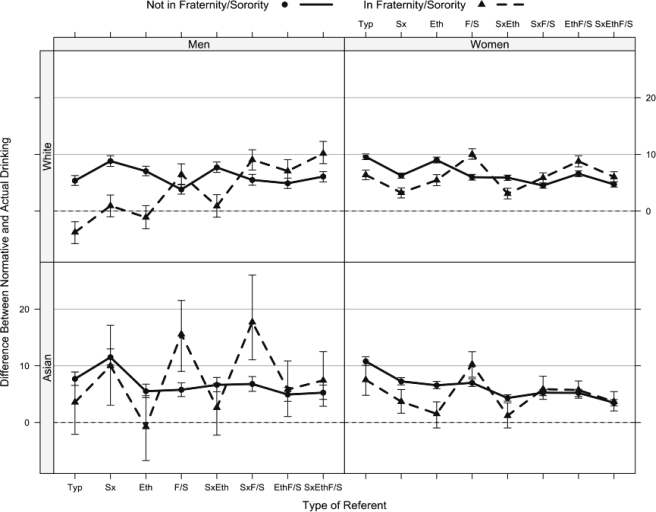

Multilevel model of difference between normative estimates and actual drinking

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate that college students overestimate true drinking rates. However, it is possible that particular subgroups are more accurate than others in their estimates. To examine this possibility, we created a new dependent variable that was the difference between the students' own reported drinking and their estimates for each of the eight referents. A multilevel model similar to that for descriptive norms was fit but used the difference score as the outcome (and without the log transformation, which was not needed). Results are found in Table 2, and means and 95% confidence intervals for each subgroup are found in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear modeling results of difference between descriptive norms and actual drinking predicted from type of referent, gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status

| Variable | df | F | P |

| Intercept | 1 | 1,382.5 | <.01 |

| Reference | 7 | 53.2 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/sorority | 1 | 8.5 | <.01 |

| Gender | 1 | 1.8 | .18 |

| Ethnicity | 1 | 0.1 | .75 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority | 7 | 392.7 | <.01 |

| Reference × Gender | 7 | 249.3 | <.01 |

| Reference × Ethnicity | 7 | 72.4 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Gender | 1 | 4.5 | <.03 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Ethnicity | 1 | 0.7 | .41 |

| Gender × Ethnicity | 1 | 2.4 | .12 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority × Gender | 7 | 62.9 | <.01 |

| Reference × Fraternity/Sorority × Ethnicity | 7 | 7.2 | <.01 |

| Reference × Gender × Ethnicity | 7 | 2.5 | <.01 |

| Fraternity/Sorority × Gender × Ethnicity | 1 | 2.3 | .13 |

Figure 3.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for difference between normative and actual drinking across eight reference groups, separately for subgroups of gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status. Means and standard deviations are reported adjacent to plotted data. Acronyms for reference groups: Typ = typical; Sx = same gender; Eth = same ethnicity; F/S = same fraternity/sorority status; SxEth = same gender and ethnicity; SxF/S = same gender and fraternity/sorority status; EthF/S = same ethnicity and fraternity/sorority status; SxEthF/S = same gender, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status.

The results show that every term in the model involving the type of referent is significant, whereas most terms not involving the type of referent are not (with the notable exception of the main effect of fraternity/sorority status). This finding reveals that, once a student's own drinking is taken into account (in the difference score), most subgroup differences based on demographic factors go away. This result is not surprising, because self-reported drinking and normative estimates of drinking are moderately correlated (r = .45), and the difference score essentially removes the students’ drinking from the variance in their normative estimates. This effect also is seen in Figure 3. Within a subgroup (i.e., the pattern of connected means within each panel of the figure), there is still notable variability, but the differences between subgroups (i.e., average effects by gender or ethnicity) are largely absent, with the exception of fraternity/sorority status.

With the difference score, a value of zero means that the drinking estimate is the same as the individual's self-reported drinking. Virtually every mean in Figure 3 is positive, indicating that, regardless of referent category or demographic subgroup, students generally overestimate others' drinking relative to their own. Fraternity/sorority students reveal several negative and near-zero difference scores and thus might be considered more accurate in their drinking estimates (and this finding is driven primarily by their higher drinking rates). However, this interpretation would apply only to reference groups not including fraternity/sorority affiliation as part of their identity. In instances where fraternity/sorority affiliation status is part of the referent group, fraternity/ sorority members (as with other demographic subgroups) overestimate normative drinking relative to their actual drinking.

Discussion

The current study was designed to extend the results of Larimer et al. (2009). It aimed to contribute to the literature regarding normative perceptions and misperceptions of drinking by examining the degree of relationship between norms for general versus more specific reference groups and actual drinking behavior and by evaluating the extent to which personal characteristics of participants (i.e., sex, ethnicity, and fraternity/sorority status) moderated these relationships. The results replicate and extend prior findings (Larimer et al., 2009), indicating that the perceived norms for reference groups at different levels of specificity vary and that, in general, students report the highest perceived norms for the most distal reference group (i.e., typical student), with perceptions becoming more accurate as similarity to the reference group increases. Despite this increasing accuracy, students perceive that all reference groups consume more alcohol than is actually the case.

Extending the social norms literature, the present findings show that, when considering specific subgroups of students (especially fraternity/sorority members and men), different patterns emerge. Specifically, members of the fraternity/sorority system reliably report higher estimates of drinking for reference groups that include fraternity/sorority status, and to a somewhat lesser extent men report higher normative estimates for reference groups that include men. Furthermore, fraternity/sorority members are more likely to report that non–fraternity/sorority reference groups drink less than they themselves drink, whereas they continue to report perceived norms for fraternity/sorority reference groups that are higher than their own drinking. This result was true for both men and women and for both Asian and White fraternity/sorority members, although the largest effects of fraternity/sorority status by reference group were noted among men.

The current research also extends the social norms literature through the inclusion of a large sample of Asian students and an evaluation of the relationship of both Asian-specific and generic ("typical student") norms to personal drinking in this population. Both types of norms were positively related to personal drinking, and, even within this relatively lower-drinking subpopulation, the norms for both Asian students and typical students are overestimated. This finding reduces concerns that the provision of normative feedback regarding typical students might increase drinking among lower-drinking subsets of the population, and it provides support for the use of normative feedback interventions for Asian students. Given the rapid growth among Asian ethnic groups in the United States (Barnes and Bennett, 2002) and recent increases in heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders in this population (Grant et al., 2004; Wechsler et al., 1998, 2002), these findings have implications for college drinking prevention in diverse populations.

The present research provides a unique contribution to the emerging literature related to social norms and drinking among college students. Early work in this area (Baer et al., 1991; Perkins and Berkowitz, 1986), indicating that perceptions of others' drinking are inaccurate overestimations and that these perceptions are strongly associated with behavior, has been consistently confirmed (Borsari and Carey, 2003). More recently, investigations have begun to consider the importance of who the "others" are, how they relate to the perceiver, and how these factors might translate into improved strategies for prevention and treatment. Although some research has considered who the "others" are from a subjective standpoint (i.e., quality of the peer relationships or how closely one identifies with the relevant group; Borsari and Carey, 2006; Neighbors et al., 2010a; Reed et al., 2007), other research has evaluated specificity as a function of more objectively defined group membership based on demographic representation (e.g., Larimer et al., 2009; Lewis and Neighbors, 2006), gender (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004; Suls and Green, 2003), and class standing (Pedersen et al., 2010), among other dimensions. The present research represents the most comprehensive evaluation of the influence of group specificity of drinking norms on alcohol consumption to date.

Results from the present research have direct implications for alcohol prevention and intervention on college campuses. Relevant to normative feedback interventions are the apparent changes occurring in who makes up these others described above, in addition to what might be the typical student on college campuses. It has been suggested that there is an increasing similarity between the general population and the college population in terms of demographic representation (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2003); because the United States is diverse, so are the nation's college campuses. This fact could have direct implications for traditional norms-based interventions describing what the typical student does, and it highlights the value of efforts (such as the current study) to understand what type of norm could be most impactful and for whom it could be most effective.

Furthermore, increased diversity on college campuses also reflects the need to be aware of potential cultural barriers to access efficacious interventions. For example, Eisen-berg and colleagues (2007) examined factors associated with failure to access clinical services among a sample of college students who screened positive for depression and felt that they needed help. One factor associated with not seeking help included less service use by those who identified as Asian or Pacific Islanders. The authors suggest that colleges and universities take steps to address issues that could interfere with student access to interventions (Eisenberg et al., 2007). Incorporating prevention elements most related to drinking by Asian students, such as ethnicity-specific normative feedback, may improve prevention efforts through increasing perceived relevance of the intervention and represents a step toward determining unique needs related to student diversity. Future research efforts designed to better understand the role of drinking norms for different reference groups in diverse populations and contexts is needed.

Despite potential advantages of incorporating more specific reference group norms into feedback-based interventions, prior research has suggested that the magnitude of the discrepancy between the perceived and actual norm, as well as discrepancy between the actual norm and one's own drinking, are important factors influencing the impact of normative feedback on drinking behavior. From this perspective, the current data suggest that provision of feedback targeting the largest discrepancy between actual and perceived norms would focus on typical student drinking behavior for the majority of students. In contrast, theories highlighting the role of reference group salience in the impact of normative feedback would suggest that, at least for members of the fraternity/sorority system, fraternity/sorority–specific feedback may have greater impact. This suggestion may be especially true for men in fraternities, who are already aware that they drink more than the typical student. Findings from the present research are congruent with recent interventions that interactively provide group-specific norms within intact groups using real-time interactive technology (LaBrie et al., 2008, 2009), and they suggest that these approaches may be especially effective for use in fraternities.

Limitations

Although a strength of the study was the inclusion of multiple sites (i.e., one large and one mid-size university), with the current sample representing approximately 5% and 20% of the undergraduate population, respectively, both institutions were located in the western United States—which may limit the generalizability to universities and colleges in different areas of the United States or in different countries. In addition, assessment at institutions smaller in size, such as small liberal arts colleges with student populations in the low thousands, might have revealed different patterns related to group membership. Furthermore, we selected ethnicity (Asian and White), sex, and fraternity/sorority affiliation as possible referents. It is possible that in other settings (e.g., schools without fraternities or sororities) alternative referents could have revealed different patterns or been viewed as more salient.

Related to methodology, questions addressing normative categories were not counterbalanced when presented to the participants, so the order in which the reference groups were introduced could have affected response sets; this could be examined in subsequent research. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported data collected over the Internet. However, research suggests that confidential surveys may enhance the reliability and validity of self-report (Babor and Higgins-Biddle, 2000; Babor et al., 1987; Chermack et al., 1998; Darke, 1998), and response rates are typically higher for web-based than for mailed surveys (McCabe et al., 2006). Although the 54% response rate for the current study is typical of Internet-based college drinking research and the obtained sample was broadly representative of the campus population, women and Asian students were somewhat over-represented—which could influence the generalizability of the results.

Finally, the study was cross-sectional by design, and both drinking and perceived norms were assessed at the same time point. There is potential for perceived norms (at varying levels of specificity) to affect students at varying points in their college career, particularly if engagement in different groups and friendship circles on campus changes throughout college (e.g., a man drops out of a fraternity during his third year; a female student joins a mostly male-dominated athletic sport club and begins spending most of her free time with male friends). Although research suggests that perceived norms are relatively stable over time, perceived norms at one time point may predict future drinking at another (Neighbors et al., 2006). Additional research evaluating how perceived norms of varying levels of specificity predict later drinking is warranted.

Conclusion

Given these findings, future research may need to be more granular in considering which normative feedback to provide for specific populations and whether to do so individually or in a group format. Continued research is needed to evaluate whether some student populations respond better to typical student feedback, whereas others benefit from feedback specific to their normative reference group. Moreover, studies will need to further integrate the role of identification with the normative reference group as a potential moderator of these treatment effects. For example, someone who more closely identifies with the student body as a whole may respond better to typical student norms, whereas someone who closely identifies with his or her ethnic group, gender, or fraternity/sorority affiliation may not.

In addition, this study did not examine reference groups that may feel more marginalized from the student body, such as sexual minority students. It is possible that more marginalized students may be particularly important to examine, because these groups may benefit most from tailored rather than generic normative feedback. Exploration of the influence of norms for majority and minority students in additional ethnic groups, such as Latino and African American students, is also an important future direction.

Footnotes

Data collection and article preparation were supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA012547.The preparation of this article also was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32AA07455 and K01AA016966.

References

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention: Dissemination strategies for medical practice and public health. Addiction. 2000;95:677–686. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Stephens RS, Marlatt GA. Verbal report methods in clinical research on alcoholism: response bias and its minimization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:410–423. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JS, Bennett CE. The Asian population: 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BD, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Changes in heavy drinking over the third decade of life as a function of collegiate fraternity and sorority involvement: A prospective, multilevel analysis. Health Psychology. 2003;22:616–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:361–370. doi: 10.1080/09595230600741339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in situational norms and attitudes toward drinking among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;54:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashin JR, Presley CA, Meilman PW. Alcohol use in the Greek system: Follow the leader? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:63–70. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Singer K, Beresford TP. Screening for alcoholism among medical inpatients: How important is corroboration of patient self-report? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1393–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. discussion 267–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Gollust SE. Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care. 2007:45,594–601. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, LaBrie JW, Lac A. The prognostic power of normative influences among NCAA student-athletes. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–45. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. (NIH Publication No. 08–6418B) [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Huchting KK, Neighbors C. A brief live interactive normative group intervention using wireless keypads to reduce drinking and alcohol consequences in college student athletes. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Pedersen ER. Live interactive group-specific normative feedback reduces misperceptions and drinking in college students: A randomized cluster trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:141–148. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Irvine D, Kilmer J, Marlatt GA. College drinking and the Greek system: Examining the role of perceived norms for high-risk behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Kaysen DL, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Lewis MA, Dillworth T, Neighbors C. Evaluating level of specificity of normative referents in relation to personal drinking behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latané B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist. 1981;36:343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Who is the typical college student? Implications for personalized normative feedback interventions. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2120–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:228–237. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CC, Globetti G. The facilitating and enhancing roles Greek associations play in college drinking. International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:1311–1322. doi: 10.3109/10826089509105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum C, Corliss HL, Mays VM, Cochran SD, Lui CK. Differences in the drinking behaviors of Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:568–574. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE. Gender differences in collegiate risk factors for heavy episodic drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Couper MP, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. Comparison of Web and mail surveys for studying secondary consequences associated with substance use: Evidence for minimal mode effects. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Depression, substance abuse and college student engagement: A review of the literature. New York, NY: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010a;24:522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010b;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08–4343, NSDUH Series H-34) [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Risky drinking in college changes as fraternity/sorority affiliation changes: A person-environment perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:219–229. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: A national study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:266–274. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Neighbors C, LaBrie JW. College students' perceptions of class year-specific drinking norms. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education programming. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:961–976. doi: 10.3109/10826088609077249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Lange JE, Ketchie JM, Clapp JD. The relationship between social identity, normative information, and college student drinking. Social Influence. 2007;2:269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Nanda S. Short- and long-term effects of fraternity and sorority membership on heavy drinking: a social norms perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Green P. Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psychology. 2003;22:479–486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology. 1982;33:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Ray-Tomasek J, Osborn CJ, Olds RS. The role of sex-specific normative beliefs in undergraduate alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2005;29:342–351. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J, Hogg M, Oakes P, Reicher S, Wetherell M. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Castillo S. Correlates of college student binge drinking. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:921–926. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: A randomized factorial study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2509–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]