Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether urological symptom clusters, as identified in previous studies, were associated with health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and use of healthcare.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The Boston Area Community Health Survey is a population-based epidemiological study of 2301 male and 3201 female residents of Boston, MA, USA, aged 30–79 years. Baseline data collected from 2002 to 2005 were used in this analysis. Data on 14 urological symptoms were used for the cluster analysis, and five derived symptom clusters among men and four among women were used in multivariate linear regression models (adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, and comorbidity) to determine their association with physical (PCS-12) and mental health component scores (MCS-12) calculated from the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form Survey.

RESULTS

For both men and women, being in the most symptomatic cluster was associated with decrements in the PCS-12 score (men, cluster 5, −10.42; women, cluster 4, −9.80; both P < 0.001) and the MCS-12 score (men, cluster 5, −9.35; women, cluster 4, −6.24; both P < 0.001) compared with the asymptomatic groups. Both men and women in these most symptomatic clusters appeared to have adequate access to healthcare.

CONCLUSION

For men and women, those with the most urological symptoms reported poorer HRQoL in two domains after adjusting for age and comorbidity, and despite adequate access to care.

Keywords: lower urinary tract symptoms, cluster analysis, urological symptoms, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Urological symptoms are receiving increasing recognition as a major public health problem in the USA [1]. The burden of urological symptoms is projected to increase, given the ageing of the population [2]. In previous studies, urological symptoms have been associated with a detrimental effect on well-being and quality-of-life (QoL) [2–5]. Moreover, recent research suggests that urological symptoms do not occur in isolation, and that rather than representing discrete entities, symptoms commonly co-occur among both men and women, as documented in population-based epidemiological studies [6,7]. Using data for 14 urological symptoms, our research group recently characterized the nature of symptom overlap among community-dwelling men and women in the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, using a cluster-analysis method that identified mutually exclusive groups considering men and women separately [8,9]. Four urological symptom clusters among women and five clusters among men were identified, with a varied number of symptoms and associated bother; we also validated the stability of these constructs [10]. Among both men and women, a very symptomatic cluster was identified, with substantial overlap of multiple symptoms; these were found to be strongly associated with medical comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors. These findings have clinical significance in that they suggest that providers should be aware that multiple symptoms might be present (complicating treatment), and that current diagnostic categories might be inadequate to capture co-occurrence of symptoms.

The goals of the present study were to extend our previous work on urological symptom clusters by examining: (i) whether clusters are associated with health-related QoL (HRQoL); and (ii) whether clusters are associated with the use of healthcare, including medication use. QoL is a clinically relevant aspect of symptom evaluation and treatment, and identified associations with HRQoL might give further relevance to these findings. Previous analyses of the BACH study compared the HRQoL impact of LUTS and urine leakage [2,5]; in the present analysis we investigated the impact of overlapping symptoms. In addition, it is important to better understand symptoms and other patient-reported outcomes in the light of their acceptance by the USA Food and Drug Administration as clinically relevant endpoints [11]. Health care use among those with urological symptoms is also of interest, to understand whether there is differential access to or use of healthcare among these populations, which also has clinical significance.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The BACH study is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) and is a population-based, epidemiological cohort study of a wide range of urological symptoms conducted among 5502 men and women aged 30–79 years residing in Boston, MA, USA. A multistage, stratified cluster sampling design was used to recruit similar numbers of people to pre-specified age groups (30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and 60–79 years), race and ethnic groups (black, Hispanic, white) and gender. This analysis used the baseline data collected between April 2002 and June 2005 during a 2-h interview conducted by a trained, bilingual interviewer, after written informed consent was obtained. Interviews for 63.3% of eligible subjects were completed, with a resulting study population of 2301 men and 3201 women, comprised of 1766 black, 1877 Hispanic and 1859 white participants. Information collected included urological symptoms, major medical conditions, use of over-the-counter and prescription drugs, anthropometrics, income, education, health behaviour, and psychosocial factors. All protocols and procedures were approved by New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board. Further details of the study design and procedures are available [12].

DEFINITION OF UROLOGICAL SYMPTOM CLUSTERS

Full details on the cluster-analysis methods, response scales and symptom thresholds are given elsewhere [8,9]. Briefly, participants who were considered symptomatic on 14 common LUTS were eligible for the cluster analysis (others were considered asymptomatic). Symptoms were captured using the IPSS, which is largely equivalent to the AUA Symptom Index [13], and the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI) scale [14]. Symptoms included urinary incontinence (any), nocturia (micturition at least twice nightly) urgency-type urinary incontinence, stress-type urinary incontinence, incomplete emptying, intermittency of urination, weak urinary stream, straining to begin urination, frequency (repeat urination within 2 h), urgency (difficulty postponing urination), dribbling after urination, wet clothes due to dribbling after urination, perceived frequency (self-report of ‘frequent urination during the day’), and urgency (using wording from the ICSI scale). To conduct the cluster analysis, we first used a hierarchical clustering approach (PROC CLUSTER, SAS version 9.1.3 [15]) to identify an appropriate number of clusters. In this approach, each subject begins as his or her own cluster and subjects are grouped into clusters according to their common symptoms. Once the number of clusters was determined, subjects were assigned to clusters using a nonhierarchical, k-means method (PROC FASTCLUS, SAS version 9.1.3 [15]). Subjects were assigned to clusters iteratively, until the solution with the minimum squared deviance was obtained. The internal validity of the cluster solution was assessed using a split-sample replication.

As described in our previous publications [8,9], the final cluster solutions were five symptom clusters among men and four among women. Among symptomatic men, about half were assigned to cluster 1, which was characterized by a low overall prevalence of the 14 symptoms (mean 1.0). Clusters 2 and 3 had intermediate levels considering the number of symptoms (mean 2.4 and 4.9 symptoms, respectively) and the predominant symptoms were frequency, perceived frequency and nocturia. Cluster 4 was characterized by 4.8 symptoms on average, which most commonly were frequency, urinary incontinence and postvoiding symptoms. Cluster 5 (containing 8% of the symptomatic men) was characterized by a high prevalence and frequency of nearly all 14 urological symptoms (mean 9.9 symptoms); nine of the 14 symptoms occurred at a prevalence of ≥72%. Among women, 54% of symptomatic women were assigned to cluster 1, which was characterized by storage symptoms including nocturia and frequency, with a mean of 1.4 symptoms among cluster 1 members. Cluster 2 was characterized by a higher prevalence of frequency and perceived frequency symptoms as well as nocturia, with a mean of 3.9 symptoms. Cluster 3 had a higher prevalence of urgency symptoms and was further distinguished by a higher prevalence of urinary incontinence than in clusters 1 and 2; the mean number of symptoms was 6.0. Cluster 4 (containing 8.3% of symptomatic women) had a high prevalence of nearly all urological symptoms (mean 10.6). Nine of the 14 symptoms occurred at a prevalence of ≥75%, with voiding symptoms generally less common than storage or postvoiding symptoms.

HRQoL

HRQoL was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12) [16]. We considered both the physical (PCS-12) and mental health component score (MCS-12) to understand separate domains of HRQoL; these scores are standardized to have a mean (sd) of 50 (10) among USA adults, with higher scores indicating a better HRQoL. Self-reported health status was also measured using the SF-12; participants reporting ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ health (combined) were compared with those rating their health ‘good’ or ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ (combined).

DEMOGRAPHIC, ANTHROPOMETRICS, COMORBIDITIES, MEDICATIONS, AND CARE-SEEKING VARIABLES

Socio-economic status (SES) was constructed as function of standardized income and education variables for the North-eastern USA and reclassified into low, middle and high [17]. Per-capita income was defined as annual household income divided by household size and was categorized into lower (≤$6000 per person), middle ($6001–30 000 per person) and upper (>$30 000 per person). Body mass index (BMI, interviewer-measured weight and height, calculated as usual) was categorized into three groups (normal <25, overweight 25–29.9, and obese >30 kg/m2). Comorbidities were selected based on their impact on QoL and the potential to be a confounder of the urological symptom-HRQoL relationship, and were based on replies to the query, ‘Have you ever been told by a health care provider that you have or had…?’ We included heart disease, vascular disease, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, diabetes (type I or type II), high blood pressure, chronic lung disease, asthma, arthritis, high blood sugar, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and kidney disease as part of a comorbidity count (0, 1, 2, 3+). (We included both high blood sugar and diabetes in the count because there were subjects who did not belong to both groups, and because we wanted to include those subjects who might have had undiagnosed or early diabetes.) Depression was considered present among participants with at least five of eight symptoms on the abridged Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [18].

Healthcare access and use were measured with the following questions: ‘How many times in the last year did you go to see a healthcare provider for any reason?’ and ‘Do you go for regular care?’, as well as the health insurance status of the participant (public only/private/none) and whether or not the participant reported trouble paying for healthcare and/or medications. With respect to medications, BACH participants were asked to gather all over-the-counter, alternative and prescription medications used in the past 4 weeks. Participants were also asked separately if they were taking drugs for specific indications. Medications labels and/or responses were in turn coded using the Slone Drug Dictionary [19], based on a modified form of the American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Pharmacologic Therapeutic Classification System [20]. Medications for urological conditions included: doxazosin, terazosin, prazosin, alfuzosin, tamsulosin, finasteride, propantheline, oxybutynin, tolterodine, hyoscyamine, pentostan polysulphate, and amitriptyline.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Due to the complex two-stage cluster sampling design, all analyses were weighted inversely proportional to the probability of being selected, and were conducted using version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN [21]. This ensures that estimates can be interpreted as representative of the community-dwelling Boston population. To examine statistically significant differences in bivariate analyses, a chi-square test was used for categorical covariates and a Wald-type test from linear regression for continuous variables. To examine the impact of clusters on HRQoL, multiple linear regression models were applied using the PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores as outcome variables. Models were adjusted for design variables (age group and race/ethnicity) and a categorical variable for comorbidities (0, 1, 2 and 3 + comorbidities). The resulting β coefficients represents the mean change in score for the cluster level compared to the asymptomatic group. Missing data were replaced by plausible values using multiple imputation (n = 25); <1% of data was missing for most variables. For income (used to construct SES), 3%, 4% and 11% were missing for white, black and Hispanic subjects, respectively. After multiple imputation, 59 subjects who previously had missing data on urological symptoms were placed into clusters using discriminant analyses; as such, compared to our previous publications on these clusters, these analyses were conducted on the full BACH sample of 3201 women and 2301 men [8,9].

RESULTS

The sociodemographic characteristics of the men and women in the BACH study population by strata of cluster assignment are presented in Table 1. Among men and women, the mean age was greater in the most symptomatic clusters (cluster 5 among men and cluster 4 among women) than in those with no symptoms. There were differences by SES and household income among men and women, with the most symptomatic clusters having the highest proportion of those with low SES and the lowest income level, and the highest proportion of persons reporting trouble paying for healthcare. Among men, the highest proportion of minorities (black and Hispanic) was in the asymptomatic group, while among women, the proportion of minority women in the asymptomatic group was similar to that in the most symptomatic cluster.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic factors by urological symptom cluster assignment among men and women (5502) in the BACH Survey, 2002–2005

| Mean (sem) or % for cluster | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | No symptoms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P* |

| Men | ||||||||

| N | 2301 | 687 | 812 | 289 | 185 | 197 | 131 | |

| Age | 47.6 (0.4) | 44.2 (0.7) | 47.1 (0.7) | 47.0 (1.1) | 50.3 (1.5) | 51.9 (1.6) | 58.9 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Education level (year) | 14.7 (0.2) | 14.6 (0.2) | 14.6 (0.2) | 14.7 (0.4) | 15.3 (0.5) | 15.0 (0.6) | 13.9 (0.6) | 0.59 |

| SES | 0.04 | |||||||

| Low | 24.3 | 23.3 | 25.1 | 27.3 | 23.0 | 14.6 | 41.1 | |

| Medium | 49.1 | 48.7 | 50.2 | 41.9 | 47.2 | 57.6 | 44.8 | |

| High | 26.6 | 28.0 | 24.7 | 30.8 | 29.7 | 27.8 | 14.1 | |

| Per-capita household income, $ | 0.01 | |||||||

| ≤6000 | 12.2 | 13.4 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 6.5 | 22.9 | |

| 6001–30 000 | 52.2 | 54.3 | 52.9 | 46.7 | 43.0 | 54.5 | 60.6 | |

| >30 000 | 35.6 | 32.2 | 35.4 | 40.7 | 44.7 | 39.0 | 16.5 | |

| Trouble paying for healthcare | 16.9 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 16.6 | 21.1 | 25.1 | 33.9 | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.005 | |||||||

| Black | 25.0 | 28.7 | 25.8 | 26.3 | 21.9 | 14.1 | 26.2 | |

| Hispanic | 13.0 | 17.9 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 7.6 | |

| White | 61.9 | 53.4 | 62.3 | 61.6 | 66.6 | 76.2 | 66.2 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| N | 3201 | 768 | 1309 | 580 | 340 | 204 | – | |

| Age | 49.2 (0.5) | 47.4 (0.9) | 48.9 (0.7) | 48.0 (0.8) | 52.4 (1.4) | 55.0 (1.5) | – | <0.001 |

| Education level (year) | 14.3 (0.1) | 14.1 (0.2) | 14.5 (0.2) | 14.3 (0.3) | 14.7 (0.3) | 12.5 (0.4) | – | <0.001 |

| SES | <0.001 | |||||||

| Low | 30.8 | 33.0 | 28.5 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 57.4 | – | |

| Medium | 45.2 | 42.4 | 46.8 | 46.1 | 47.9 | 35.5 | – | |

| High | 23.9 | 24.5 | 24.8 | 25.4 | 24.7 | 7.1 | – | |

| Per-capita household income, $ | 0.009 | |||||||

| ≤6000 | 20.6 | 21.6 | 19.9 | 19.2 | 15.7 | 38.1 | – | |

| 6001–30 000 | 49.8 | 50.2 | 47.6 | 52.2 | 53.4 | 48.1 | – | |

| >30 000 | 29.7 | 28.3 | 32.5 | 28.6 | 30.9 | 13.8 | – | |

| Trouble paying for healthcare | 18.5 | 12.5 | 16.5 | 20.6 | 22.2 | 41.4 | – | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||||||

| Black | 29.9 | 31.2 | 33.3 | 22.9 | 24.9 | 35.7 | – | |

| Hispanic | 13.3 | 17.5 | 13.7 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 14.0 | – | |

| White | 56.8 | 51.3 | 53.0 | 66.7 | 66.0 | 50.3 | – | |

P for the chi-square test of heterogeneity or Wald F-test (for continuous variables) across levels of cluster variable. All estimates were weighted by the inverse of the probability of being sampled.

Considering comorbidities by cluster membership, we previously reported a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and high blood pressure in the most symptomatic cluster than in those with no symptoms among both men and women [8,9]. Table 2 presents the proportion of those with 0, 1, 2 and 3 + comorbidities, considering an expanded list of 12 comorbidities. Among men, the highest burden of comorbidity was in cluster 5, followed by cluster 3; 45.8% of men in cluster 5 had three or more comorbidities (Table 2). Similarly, among women, the most symptomatic cluster 4 had the highest burden of comorbidity, with 52.9% reporting three or more comorbidities (Table 2). The prevalence of depression was ≈50% in the most symptomatic clusters among men and women, as was the prevalence of self-reported fair or poor health.

TABLE 2.

HRQoL, symptom interference, comorbidities and healthcare use by urological symptom cluster assignment among men and women (5502) in the BACH Survey, 2002–2005

| Mean (sem) or % for cluster | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | No symptoms | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | P* |

| Men | 2301 | 687 | 812 | 289 | 185 | 197 | 131 | |

| PCS | 50.3 (0.3) | 52.4 (0.5) | 50.8 (0.4) | 51.7 (0.7) | 48.5 (1.0) | 48.4 (1.2) | 37.0 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| MCS | 50.4 (0.4) | 52.3 (0.6) | 51.2 (0.4) | 49.4 (1.2) | 47.3 (1.5) | 49.3 (1.0) | 43.4 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity | <0.001 | |||||||

| None | 45.4 | 60.3 | 45.8 | 44.9 | 28.3 | 31.2 | 22.7 | |

| 1 | 25.8 | 22.8 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 30.4 | 27.3 | 18.9 | |

| 2 | 14.2 | 9.4 | 15.4 | 14.3 | 12.8 | 23.2 | 12.7 | |

| ≥3 | 14.6 | 7.5 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 28.6 | 18.4 | 45.8 | |

| Reporting fair or poor health | 15.0 | 10.8 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 24.6 | 11.4 | 51.2 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 14.0 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 15.7 | 23.2 | 19.2 | 50.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.45 | |||||||

| <25.0 | 26.6 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 24.6 | 26.4 | 29.3 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 40.7 | 40.0 | 40.8 | 44.7 | 49.6 | 36.0 | 27.5 | |

| ≥30.0 | 32.7 | 30.0 | 34.2 | 30.3 | 25.8 | 37.6 | 43.2 | |

| Type of health insurance | <0.001 | |||||||

| Private | 67.2 | 69.0 | 68.7 | 74.2 | 55.2 | 67.7 | 45.8 | |

| Public only | 18.1 | 13.5 | 17.8 | 16.3 | 29.6 | 11.0 | 47.6 | |

| None | 14.7 | 17.6 | 13.5 | 9.5 | 15.2 | 21.3 | 6.6 | |

| Goes for regular medical care | 76.9 | 71.4 | 75.4 | 75.5 | 89.1 | 79.9 | 94.7 | <0.001 |

| Median healthcare provider visits/year | 3.1 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 9.8 | |

| Taking urological medications | 4.7 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 4.3 | 14.0 | 0.02 |

| Women | 3201 | 768 | 1309 | 580 | 340 | 204 | – | |

| PCS | 48.2 (0.3) | 51.5 (0.4) | 49.2 (0.4) | 46.9 (0.7) | 46.6 (1.0) | 35.6 (1.3) | – | <0.001 |

| MCS | 49.2 (0.3) | 51.0 (0.4) | 50.0 (0.5) | 49.1 (0.6) | 46.0 (1.3) | 43.8 (1.4) | – | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity | <0.001 | |||||||

| None | 38.7 | 52.8 | 39.2 | 37.7 | 24.0 | 13.5 | – | |

| 1 | 26.4 | 24.0 | 27.5 | 28.0 | 29.6 | 13.4 | – | |

| 2 | 16.0 | 13.3 | 15.4 | 17.1 | 19.6 | 20.1 | – | |

| ≥3 | 18.9 | 9.9 | 17.8 | 17.2 | 26.9 | 52.9 | – | |

| Reporting fair or poor health | 17.8 | 12.5 | 17.0 | 16.8 | 17.2 | 51.7 | – | <0.001 |

| Depression | 20.1 | 17.3 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 26.6 | 49.5 | – | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001 | |||||||

| <25.0 | 33.3 | 38.4 | 32.4 | 35.7 | 31.6 | 14.2 | – | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 28.6 | 29.2 | 29.8 | 29.1 | 27.2 | 17.6 | – | |

| ≥30 | 38.1 | 32.4 | 37.8 | 35.2 | 41.1 | 68.2 | – | |

| Type of health insurance | <0.001 | |||||||

| Private | 61.4 | 61.5 | 61.9 | 66.7 | 63.8 | 30.3 | – | |

| Public only | 29.4 | 27.8 | 27.9 | 24.0 | 32.0 | 63.6 | – | |

| None | 9.2 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 4.2 | 6.1 | – | |

| Goes for regular medical care | 93.9 | 91.3 | 94.2 | 93.7 | 96.5 | 97.2 | – | 0.03 |

| Median healthcare provider visits/year | 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 6.4 | 9.8 | – | |

| Taking urological medications | 3.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 18.3 | – | <0.001 |

P for the chi-square test of heterogeneity or Wald F-test (for continuous variables) across levels of cluster variable. All estimates were weighted by the inverse of the probability of being sampled.

The increased burden of comorbidities in the most symptomatic clusters was also accompanied by greater use of healthcare. Among men, the clusters with the highest number of symptoms (clusters 5 and 3) showed the largest median number of annual visits to a healthcare provider, as well as the highest proportion reporting going for regular care; the pattern was the same among women in cluster 4. Men and women in the most symptomatic clusters were more likely to have any type of insurance coverage and were more likely to have only public insurance than were the other groups. Although the overall prevalence of use of urological medications was low (<5% in either gender), it was highest in the more symptomatic clusters in both men and women.

The mean PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores for men and women were lower in the most symptomatic clusters, indicating a poorer HRQoL. Compared to the PCS-12 score among asymptomatic men (52.4), the cluster 5 mean was lower (37.0). Similarly, among women, the mean PCS-12 score was 51.5 among those without symptoms, in contrast to 35.6 in cluster 4. MCS-12 scores were also significantly different across clusters among men and women, with the lowest scores in the most symptomatic clusters (means of 43.4 among men in cluster 5 and 43.8 among women in cluster 4), while scores in the asymptomatic groups were similar to the standardized score of 50 in the USA population.

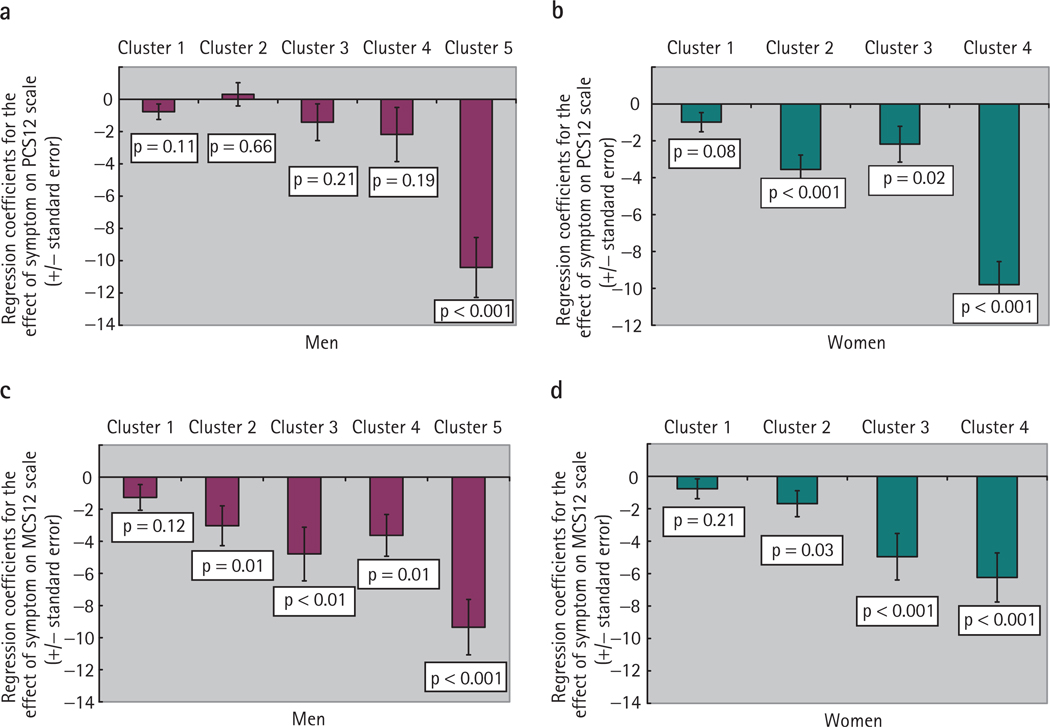

Because greater age and the greater burden of comorbidity were likely confounders of the relationship between the most symptomatic clusters and HRQoL measures, we used multivariate linear regression models to adjust for the influence of age, race and comorbidity (Fig. 1). For the PCS-12 score among men, being in cluster 5 was associated with a −10.42 unit change on the scale (P < 0.001, exceeding one sd) compared to the asymptomatic group. For MCS-12 scores among men, membership in any cluster (except cluster 1) was significantly associated with a negative shift on the scale, with the most pronounced shift again being in Cluster 5 (− 9.35, P < 0.001). Among women, all clusters were significantly associated with a lower physical health score, as shown by the PCS-12 score, with a shift of similar magnitude to the men in the most symptomatic cluster (−9.80 for cluster 4, P < 0.001). For mental health (MCS-12), clusters 3 and 4 were associated with shift of −4.96 for cluster 3 and −6.24 for cluster 4 (both P < 0.001).

FIG. 1.

The relative impact of cluster membership on HRQoL: regression coefficients with SEs for the PCS-12 for men (a) and women (b), and the MCS-12 for men (c) and women (d). Models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and comorbidity.

DISCUSSION

In a population-based sample we sought to examine whether previously identified urological symptom clusters were associated with HRQoL and use of healthcare. While men and women in the most symptomatic clusters were older, of lower income and SES than those with no symptoms, they did not appear less likely to be insured and appeared to have adequate access to medical care, as reflected in annual visits to providers (although also reported more trouble paying for care and/or medications). Among both men and women, even after adjustment for the greater burden of comorbidity among the more symptomatic clusters, there remained a substantial association with both physical and mental health QoL scores, suggesting that the association was not due exclusively to the presence of comorbidity and poorer overall health status. There was a high prevalence of depression in the most symptomatic clusters, but due to its interrelationship with the mental health score we did not adjust for it in models for MCS-12. However, adjustment for depression in the PCS-12 models did not substantially change the results observed for the cluster variable (data not shown). Whereas PCS-12 scores were more similar by gender, there was a larger negative impact on MCS-12 scores of being in the most symptomatic cluster for men than for women, perhaps indicating that overlapping urological symptoms especially affect this domain of QoL for men.

Previous investigations of urological symptoms have found a significant association with HRQoL, e.g. in the BACH Survey, an investigation of LUTS as well as weekly urine leakage found that the impact on physical and mental health was roughly comparable to or greater than the impact of diabetes among both men and women [2]. The cluster analysis method has the ability to capture the overlap or co-occurrence of 14 urological symptoms, and the large impact on HRQoL in the most symptomatic clusters suggests that more symptoms are potentially contributing in an additive or multiplicative fashion to HRQoL.

The cluster analysis method is considered exploratory and is associated with certain conceptual and methodological limitations [22]. However, our previous work has replicated the clusters [8,9] and explored the impact of including different symptoms, the use of continuously scaled vs dichotomous thresholds, and compared our study population cluster analysis results to an external cohort, with relatively consistent results [10]. The substantial association of the most symptomatic clusters with two different domains of HRQoL in the present analysis might be viewed as further validation that these are a clinically meaningful state. Additional strengths of the present analysis are the inclusion of both genders, a diversity of age range, race/ethnicity and SES, and known general applicability of the comorbidities in the study population [12,23].

These data show that urological symptoms not only co-occur but also are prevalent with many other comorbidities. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data used for this analysis, we are unable to determine if a poor HRQoL due to comorbidities or their treatment preceded urological symptoms, or if urological symptoms resulted in poorer HRQoL. Similarly, it is not possible to conclude that treatment of urological symptoms would necessarily improve HRQoL over and above treatment of associated comorbidities.

Another limitation is that although we attempted to adjust for the influence of comorbidity in our models, we might have missed undiagnosed conditions (despite the broad range of included comorbidities that could affect HRQoL). However, despite its limitations, our study has clinical implications. Cluster analyses provide an innovative way of identifying patient groups with interrelated symptoms with potentially important other medical comorbidities (such as features of the metabolic syndrome), which have previously been masked by emphasis on associating all LUTS solely with specific disease entity labels, such as prostate disease in the male, sphincteric weakness and pelvic floor disorders in the female, and detrusor overactivity in both sexes. This approach is consistent with a new, broader consensus emphasising recognition of the lower urinary tract as an integrated unit (but also influenced by a wide range of systemic factors and medical comorbidities), rather than exclusive use of discrete organ-based symptom derivations [24]. The strong association of multiple urological symptoms with comorbidity suggests that primary-care clinicians should consider a high likelihood of having coexisting urological problems when evaluating patients presenting with multiple medical conditions, and vice-versa. This interrelationship has implications for the design and delivery of new therapies, while complicating clinical treatment (as well as the secondary prevention of comorbidities) and emphasising the importance of the overall assessment of any patient presenting with LUTS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Gretchen R. Esche for programming assistance and Deborah Brander for proofreading and editing.

Funding for the BACH Survey is provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (NIH) DK 56842. Additional funding was provided from Pfizer, Inc for analyses presented in this paper. Susan A. Hall, Carol L. Link, Sharon L. Tennstedt and Raymond C. Rosen are employees of NERI, who received funding from Pfizer in connection with the development of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- (HR)QoL

(health-related) quality-of-life

- PCS

Physical Health Component Score

- MCS

Mental Health Component Score

- BACH

Boston Area Community Health

- ICSI

Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index

- SF-12

Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form Survey

- SES

socioeconomic status

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK or the NIH. The corresponding author retains the right to provide a copy of the final manuscript to the NIH upon acceptance for publication, for public archiving in PubMed Central as soon as possible but no later than 12 months after publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Litwin MS, Saigal CS. Urologic Diseases in America. Vol. 2007. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litman HJ, McKinlay JB. The future magnitude of urological symptoms in the USA: projections using the Boston Area Community Health survey. BJU Int. 2007;100:820–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07018.x. (erratum BJU Int 2007; 100 : 971) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–1395. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarpero HM, Fiske J, Xue X, Nitti VW. American Urological Association Symptom Index for lower urinary tract symptoms in women: correlation with degree of bother and impact on quality of life. Urology. 2003;61:1118–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kupelian V, Wei JT, O’Leary MP, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2381–2387. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry MJ, Link CL, McNaughton-Collins MF, McKinlay JB. Overlap of different urological symptom complexes in a racially and ethnically diverse, community-based population of men and women. BJU Int. 2007;101:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne K, Matza LS, Kopp ZS, et al. Examining lower urinary tract symptom constellations using cluster analysis. BJU Int. 2008;101:1267–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Çinar A, Hall SA, Link CL, et al. Cluster Analysis and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) in Men: findings from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. BJU Int. 2008;101:1247–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall SA, Çinar A, Link CL, et al. Do urologic symptoms cluster among women? Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. BJU Int. 2008;101:1257–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen RC, Coyne KS, Henry D, et al. Beyond the cluster: methodological and clinical implications in the Boston Area Community Health survey and EPIC studies. BJU Int. 2008;101:1274–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.USA Food and Drug Administration. [accessed 3 June, 2007];The Importance of Patient-Reported Outcomes… It’s All About the Patients. available at http://fda.gov/fdac/features/2006/606_patients.html.

- 12.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg. Design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, Whitmore KE, Spolarich-Kroll J. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAS Institute Inc. SAS. 9.1.3 Help and Documentation. Cary, NC: SAS; 2002–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley KE, Kelley TP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. The Slone Drug Dictionary: a research driven pharmacoepidemiology tool. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12:168–169. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. AHFS. Drug Information. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Cluster analysis in family psychology research. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:121–132. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New England Research Institutes. Comparison of BACH batch 1–4 data with data from three national surveys (NHIS, NHANES, and BRFSS) Web-based technical report. New England Research Institutes; 2006. Can the BACH data be generalized to the U.S. population? [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapple CR, Wein AJ, Abrams P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms revisited: a broader clinical perspective. Eur Urol. 2008;54:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]