Abstract

Objective

Animal studies suggest that regulatory T (Treg) cells play a beneficial role in ventricular remodeling and our previous data have demonstrated defects of Treg cells in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF). However, the mechanisms behind Treg-cell defects remained unknown. We here sought to elucidate the mechanism of Treg-cell defects in CHF patients.

Methods and Results

We performed flow cytometry analysis and demonstrated reduced numbers of peripheral blood CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45RO−CD45RA+ naïve Treg (nTreg) cells and CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45RO+CD45RA− memory Treg (mTreg) cells in CHF patients as compared with non-CHF controls. Moreover, the nTreg/mTreg ratio (p<0.01), CD4+CD25+FOXP3+CD45RO− CD45RA+CD31+ recent thymic emigrant Treg cell (RTE-Treg) frequency (p<0.01), and T-cell receptor excision circle levels in Treg cells (p<0.01) were lower in CHF patients than in non-CHF controls. Combined annexin-V and 7-AAD staining showed that peripheral Treg cells from CHF patients exhibited increased spontaneous apoptosis and were more prone to interleukin (IL)-2 deprivation- and CD95 ligand-mediated apoptosis than those from non-CHF individuals. Furthermore, analyses by both flow cytometry and real-time polymerase chain reaction showed that Treg-cell frequency in the mediastinal lymph nodes or Foxp3 expression in hearts of CHF patients was no higher than that of the non-CHF controls.

Conclusion

Our data suggested that the Treg-cell defects of CHF patients were likely caused by decreased thymic output of nascent Treg cells and increased susceptibility to apoptosis in the periphery.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is regarded as a state of chronic inflammation with elevated T-cell activation and inflammatory cytokine production in the circulatory system [1], [2]. However, the pathogenic mechanisms responsible for this abnormal immune activation remain unknown. Treg cells represent a unique lineage of T cells that play an essential role in the modulation of immune responses and the control of potentially harmful immune activations because of their immunoregulatory and immunosuppressive characteristics [3]. Among the several types of Treg cells that have been defined, one particular subset that constitutively expresses CD4, CD25 and the transcription factor Foxp3 has received much attention. Alterations in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg-cell number or function is directly associated with the pathogenesis of several common human diseases, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [4], [5], multiple sclerosis [6], type 1 diabetes [7], and rheumatoid arthritis [8]. Adoptive transfer of purified Treg cells suppresses immune injury and improves recovery in animal disease models [9]–[12].

Adverse ventricular remodeling occurs upon acute and chronic injury regardless of etiology, and it is related to poor prognosis of patients with heart failure [13]. There is compelling evidence that inflammatory mechanisms contribute to the process of adverse ventricular remodeling [14]. In animal models of heart failure, previous studies demonstrated that Treg cells could be a target of heart failure therapeutics because CCR5-mediated Treg-cell recruitment in the infarcted heart [15] and adoptively transferred Treg cells [16] provided protection from adverse cardiac remodeling by preventing expansion of inflammation and fibrosis after adoptive transfer. In a previous publication, we found that circulating Treg cells were reduced and their function was altered in CHF patients, regardless of etiology, suggesting that the defects in Treg cells are responsible for the aberrant chronic immune activation in CHF patients [17]. It is believed that the understanding of mechanisms underlying Treg-cell defects in CHF patients is of great significance, especially with respect to therapy through Treg-cell manipulation. In the present study, we attempt to explore the mechanisms that might account for the Treg-cell defects in CHF patients by studying Treg-cell production, survival, and tissue reallocation in these patients.

Results

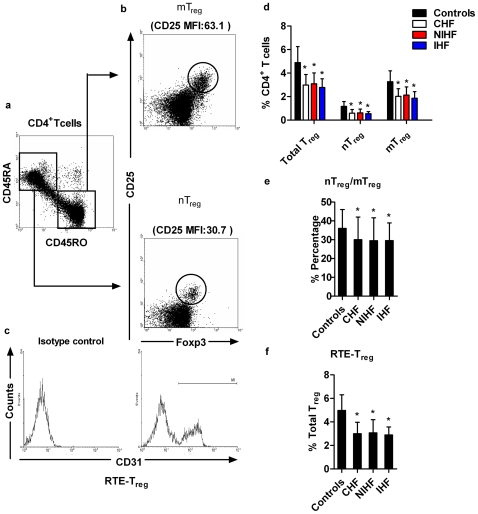

1. Reduced nTreg-, mTreg- and RTE-Treg-cell frequency in CHF patients

To determine the number of total Treg cells and Treg subsets, PBMCs were obtained from 52 CHF patients and 43 age-matched non-CHF controls followed by 6-color flow cytometric analysis. Basic clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Within the naïve CD4+CD45RA+CD45RO− (R1 in Figure 1A) or memory CD4+CD45RA−CD45RO+ (R2 in Figure 1A) T cells, a small subpopulation of cells with high expression of both CD25 and Foxp3 could be readily detected. mTreg cells were characterized as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ CD45RA− CD45 RO+ cells (R3 in Figure 1B, upper panel) and nTreg cells were characterized as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+CD45RA+CD45RO− cells (R4 in Figure 1B, lower panel). nTreg cells exhibited a lower expression of CD25 as compared with mTreg cells (mean fluorescent intensity, MFI: nTreg vs. mTreg: 24.1±5.4 vs. 54.6±8.7, p<0.01). RTE-Treg cells were identified as CD31 co-expressing nTreg cells (Figure 1C). The proportion of Treg cells in total CD4+ T cells was significantly decreased in CHF patients when compared with non-CHF subjects (Figure 1D). The percentages of nTreg and mTreg cells within CD4+ T cells were also significantly lower in CHF patients than in age-matched non-CHF subjects (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: nTreg: 1.17±0.41% vs. 0.59±0.31%, p<0.01; mTreg: 3.27±0.92% vs. 2.02±0.65%, p<0.01; Figure 1D). CHF patients showed a significantly lower nTreg/mTreg ratio (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: 36±10% vs. 30±12%, p<0.05; Figure 1E). Furthermore, we observed that proportions of RTE-Treg cells in the total Treg-cell population in CHF patients were significantly reduced when compared to age-matched, non-CHF controls, suggesting that thymic production of Treg cells was impaired in CHF patients (non-CHF vs. CHF: 4.97±.34% vs. 3.00±0.97%, p<0.01; Figure 1F). However, no difference in total Treg, nTreg, mTreg, and RTE-Treg cells between IHF or NIHF patients was observed (Figure 1D–F). Similar results were obtained when we compared the absolute numbers of total Treg, nTreg, mTreg, and RTE-Treg cells between CHF patients and non-CHF controls (Table 2).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of study population.

| CHF patients (n = 52) | NIHF patients (n = 32) | IHF patients (n = 20) | Non-CHF controls(n = 43) | |

| Age (year) | 44±13 | 40±14 | 51±8 | 42±12 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 31/21 | 17/15 | 14/6 | 28/15 |

| NYHA (II/III/IV) | 25/21/6 | 12/16/4 | 13/5/2 | — |

| LVEF (%) | 35.38±6.24 | 35.06±6.41 | 35.9±6.09 | — |

| LVEDD (cm) | 6.11±0.47 | 6.16±0.5 | 6.02±0.41 | — |

| Hypertension (%) | 37 | 16 | 70 | 0 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) | 2955.52±1971.55 | 2756.33±1628.37 | 3176.8±2442.88 | — |

| Medication (%) | ||||

| ACEI/ARBs | 90 | 91 | 90 | 0 |

| Antisterone | 42 | 47 | 35 | 0 |

| Digitalis | 31 | 28 | 35 | 0 |

| β-Blocker | 87 | 88 | 85 | 0 |

| Diuretics | 73 | 50 | 80 | 0 |

Data is presented as mean±SD, or number or percentage of patients or healthy controls (HCs). NIHF: non-ischemic heart failure; IHF: ischemic heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; NT-ProBNP, N-terminal Pro B-type natriuretic peptide; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Figure 1. Frequencies of the regulatory T (Treg)-cell subset in CHF patients and non-CHF controls.

PBMCs of CHF patients (n = 52, 32 NIHF and 20 IHF) and non-CHF controls (n = 43) were included, and a 6-color flow cytometric analysis using mAbs specific for CD4, CD25, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD31 and Foxp3 was performed. a. Representative FACS images from a non-CHF control. Dot plots show CD45RA and CD45RO expression on gated CD4+ T cells. Naïve and memory CD4+ T cells were defined as CD45RA+CD45RO− (R1) and CD45RA−CD45RO+ (R2), respectively. b. A small subpopulation of memory Treg (mTreg) (upper panel) and naïve Treg (nTreg) (lower panel) cells expressing both CD25 and Foxp3 was detectable. c. Histograms show the expression of CD31 on nTreg cells. Recent thymic export-Treg (RTE-Treg) cells were identified as CD4+CD25+Foxp3+CD45RA+CD45RO−CD31+ cells. d. Frequencies of total Treg, nTreg, and mTreg cells in different patient populations were determined as percentages of total CD4+ T cells. e. The ratio of nTreg to mTreg cells in different subject populations. f. RTE-Treg cell frequency in different subject populations was presented as a percentage of total Treg cells. *p<0.05 vs. non-CHF controls.

Table 2. Absolute number of Treg, nTreg, mTreg and RTE-Treg in the study population.

| CD4+ T cells (106/L) | Treg (106/L) | nTreg (106/L) | mTreg (106/L) | RTE-Treg (106/L) | |

| CHF patients (n = 52) | 341.95±206.28 | 9.92±5.78* | 1.92±1.24* | 6.84±4.30* | 0.31±0.24* |

| NIHF patients (n = 32) | 346.55±205.81 | 10.52±6.26* | 2.06±1.37* | 7.38±4.81* | 0.35±0.29* |

| IHF patients(n = 20) | 334.60±212.16 | 8.96±4.92* | 1.69±0.97* | 5.97±3.27* | 0.25±0.13* |

| Non-CHF controls (n = 43) | 289.99±155.36 | 13.96±7.6 | 3.33±2.07 | 9.51±5.49 | 0.70±0.43 |

Data is presented as mean±SD. Treg, regulatory T cells; nTreg, naïve Treg; mTreg, memory Treg; RTE-Treg, recent thymic emigrant Treg. *p<0.05 vs. non-CHF controls.

Consistent with our previous report [17], we observed that total Treg number was negatively correlated with NT-proBNP in CHF patients. Furthermore, the present study also found that NT-proBNP and nTreg or mTreg numbers were negatively correlated (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation analysis between Treg or its subset frequency and NT-proBNP in CHF patients.

| NT-proBNP | |||

| Treg | nTreg | mTreg | |

| Coefficients | −0.589 | −0.557 | −0.446 |

| p values | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

NT-proBNP, N-terminal Pro B-type natriuretic peptide; Treg, regulatory T cells; nTreg, naïve Treg; mTreg, memory Treg.

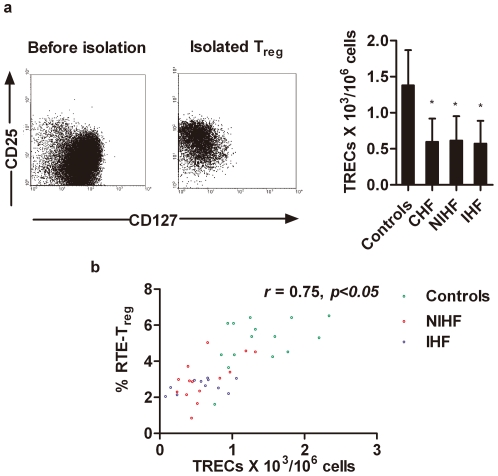

2. Decreased intracellular TREC levels in Treg cells from CHF patients

TREC is a marker for nascent thymic T cells [18]. We studied intracellular levels of TRECs in Treg cells isolated from 25 CHF patients and 15 age-matched non-CHF subjects using quantitative real-time PCR. Flow cytometry was used to determine the purity of Treg cells after cell sorting (Figure 2A, left panel). The TREC content in Treg cells was significantly lower in CHF than that in non-CHF patients (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: 1.38±0.49×103/106 cells vs. 0.60±0.32×103/106 cells, p<0.01; Figure 2A, right panel). There was no significant difference in Treg-cell TREC content between IHF and NIHF patients. Spearman's correlation test revealed a positive association between Treg-cell TREC level and RTE-Treg cell proportion in both CHF patients and non-CHF controls (r = 0.75, p<0.001; Figure 2B).

Figure 2, Analysis of intracellular T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC) levels in purified Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls.

a. CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg cells from CHF patients (n = 25, 14 NIHF and 11 IHF) and non-CHF controls (n = 15) were isolated by magnetic selection (left), and the TREC levels were determined by RT-PCR (right; *p<0.01) and compared to non-CHF controls. b. RTE-Treg frequencies were plotted against TREC levels in purified Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls (r = 0.75, p<0.001).

3. Increased spontaneous and IL-2 deprivation/Fas-mediated apoptosis in Treg cells from CHF patients

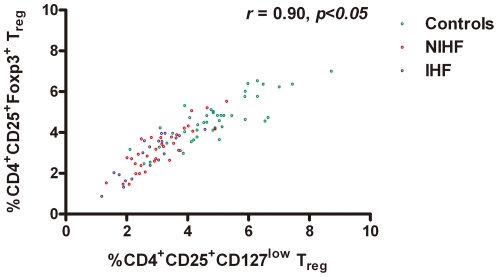

Increased apoptosis and decreased survival could be a mechanism of Treg-cell defects in CHF patients. Because of the fixation and permeabilization procedures used for detecting Treg cells using Foxp3 antibodies by FACS, we detected apoptotic Treg cells with antibodies against CD127, a newly identified Treg surface marker that correlates well with Foxp3 [19]. In both CHF patients and non-CHF controls, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells were correlated with CD4+CD25+CD127low/− Treg cells (r = 0.91, p<0.001, Figure 3). When we gated the CD4+CD25+CD127low/− cells, we found that when this cell population was derived from CHF patients, irrespective of the etiology, there was a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic annexin V+7-AAD− cells than when derived from non-CHF controls (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: 8.79±3.37% vs. 14.78±4.08%, p<0.01; Figure 4A).

Figure 3. Correlation between CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ Treg cells and CD4+CD25+CD127lowTreg cells.

Frequencies of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells were plotted against CD4+CD25+CD127lowTreg cells in 47 CHF patients and 38 non-CHF controls (r = 0.91, p<0.001).

Figure 4. Spontaneous apoptosis of Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls.

PBMCs of 47 CHF patients and 38 non-CHF controls were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25, anti-CD127, annexin-V and 7-AAD and analyzed by flow cytometry. a. Representative FACS analyses from one non-CHF control and one CHF patient are shown. A small subpopulation of CD25+CD127low/− cells were gated and identified as Treg cells (left panels). The staining of annexin-V and 7-AAD was further analyzed on gated Treg cells (middle), and apoptosis levels of the Treg cells are calculated as percentage of annexin-V+7-AAD− cells among 7-AAD− cells (right; *p<0.01 vs. non-CHF controls). b. CD4+CD25+CD127low/− Treg cells from CHF patients (n = 25, 14 NIHF and 11 IHF) and non-CHF controls (n = 15) were isolated by magnetic selection (left), and the expression of both the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 (top panel) and the pro-apoptotic gene Bak (bottom panel) was measured. *p<0.05 vs. non-CHF controls.

Enhanced apoptosis often correlates with altered expression of apoptosis-associated genes. We compared the levels of anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 and pro-apoptotic gene Bak expression between CD4+CD25+CD127low/− Treg cells isolated from CHF patients and non-CHF controls. Significantly lower Bcl-2 expression (p<0.01) and higher Bak expression (p<0.01) were observed in Treg cells from CHF patients when compared with those from non-CHF controls (Figure 4B).

IL-2 is essential for the development, function and homeostasis of Treg cells [20]. However, human Treg cells do not produce this cytokine and therefore are susceptible to IL-2 deprivation, which leads to Treg-cell apoptosis [21]. Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls might exhibit different susceptibilities to IL-2 deprivation. To test this hypothesis, we incubated Treg cells from the different patient populations with anti-human IL-2 monoclonal antibodies for 3 days. Treg cells from CHF patients were more sensitive to IL-2 deprivation-induced apoptosis when compared with Treg cells from non-CHF subjects (non-CHF vs. CHF: 22.35±4.12% vs. 33.26±5.89%, p<0.01; Figure 5A).

Figure 5. IL-2 deprivation and FasL-mediated Treg-cell apoptosis.

PBMCs were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25, anti-CD127, and apoptosis was induced as described in Methods. a. IL-2 deprivation-mediated Treg-cell apoptosis between CHF patients (n = 47) and non-CHF controls (n = 38).b. CD95 expression on gated Treg cells from CHF patients (n = 47) and non-CHF controls (n = 38). c. CD95L induced a dose-dependent apoptosis of Treg cells from CHF patients after incubation with CD95L for 12 h (upper panel; data are means from three separate experiments). Apoptosis of Treg cells from CHF patients in the presence of 100 ng/ml CD95L was plotted against time (lower panel; data are means from three separate experiments). d. FasL-induced apoptosis of Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls (100 ng/ml FasL for 12 hrs). e. ELISA determination of plasma soluble FasL levels in 47 CHF patients and 38 non-CHF controls. *p<0.05 vs. non-CHF controls.

Treg-cell apoptosis could also be induced by the interactions between death receptor CD95 with the CD95 ligand (CD95L) [22]. Human Treg cells constitutively express these death receptors and are thus highly sensitive to CD95-CD95L-mediated apoptosis [23]. Increased apoptosis in Treg cells from CHF patients suggests that Treg cells from these patients express high levels of CD95 and/or are more sensitive to CD95L. To test this hypothesis, we compared the expression level of CD95 and sensitivity toward CD95L-triggered apoptosis in Treg cells from CHF patients and non-CHF controls. CD95 expression on Treg cells from CHF patients was significantly higher than on Treg cells from non-CHF controls (non-CHF vs. CHF: 73.78±8.12% vs. 84.30±6.67%, p<0.01; Figure 5B). CD95L induced apoptosis of Treg cells from CHF patients in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 5C). CD95L initiated Treg-cell apoptosis in 3 hrs, but apoptosis reached a peak after 12 hrs of induction. When incubated with 100 ng/ml of CD95L for 12 hrs, Treg cells prepared from CHF patients showed higher percentages of cells undergoing CD95L-induced apoptosis than in non-CHF subjects (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: 19.43±6.87% vs. 36.52±12.03%, p<0.01; Figure 5D). These observations could explain the increased Treg-cell apoptosis in CHF patients (Figure 4A). Furthermore, we detected significantly higher plasma levels of soluble CD95L in CHF patients than in non-CHF controls (non-CHF vs. CHF patients: 77.28±5.26% vs. 101.22±5.06%, p<0.01; Figure 5E). Among the CHF subgroups IHF and NIHF, we did not detect any differences in either IL-2 deprivation- or CD95-mediated Treg-cell apoptosis (Figure 5A/5D). Plasma CD95L levels were also similar between CHF, IHF, and NIHF patients (Figure 5E). Taken together, these findings suggest that Treg cells from CHF patients were more prone to apoptosis and that IL-2 and CD95/CD95L might be involved in regulation of Treg-cell survival.

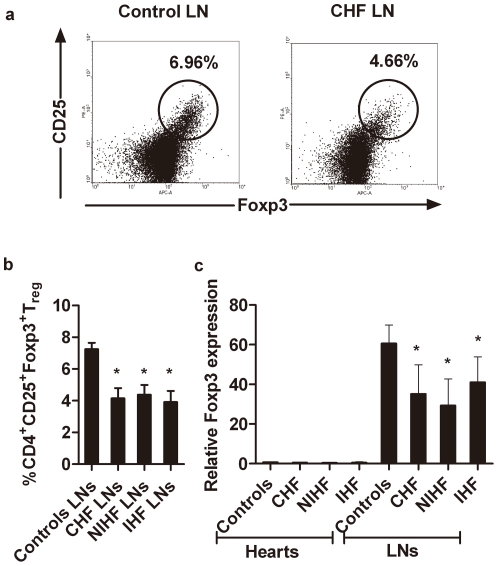

4. Treg cells accumulate neither in mediastinal lymph nodes nor in failing hearts

One possible explanation for reduced Treg-cell number in CHF patients is the reallocation of these cells to the lymph nodes or disease-affected organs. We compared the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells to total CD4+ T cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes from CHF patients and non-CHF controls. Mediastinal lymph node Treg cells from CHF patients were significantly fewer than from non-CHF controls (Figure 6A/6B). Total lymphocyte Foxp3 mRNA levels were also significantly lower in CHF, IHF and NIHF patients than in non-CHF controls (Figure 6C). To examine whether Treg cell accumulation in the heart was different between CHF and non-CHF controls, Foxp3 RT-PCR was performed on biopsied cardiac samples. No difference was found between failing hearts and hearts from donors, although Foxp3 levels were low in all tested heart samples (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Treg cells in mediastinal lymph nodes and hearts.

a. Representative FACS dot plots showed the presence of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes. b. Percentages of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes were determined in six CHF patients (three with idiopathic cardiomyopathy and three with ischemic cardiomyopathy) and three controls without cardiomyopathy. c. Comparison of Foxp3 expression in the mediastinal lymph nodes and hearts of CHF and non-CHF controls. *p<0.05 vs. non-CHF controls.

Discussion

As the final common pathway of many cardiovascular diseases, CHF is a complex multi-step disorder and several mechanisms participate in its pathogenesis. There is compelling evidence that inflammation and autoimmune abnormalities play an important role in the progression of heart failure [1], [24], [25]. Various autoantibodies, which are directed against different cardiac antigens, such as cardiac myosin, cardiac troponin I, cardiolipin, beta1-adrenergic and M2 muscarinic receptors can be detected in the serum of patients with NIHF or IHF [26]–[29]. These autoantibodies can lead to cardiac injury, and they correlate with the deterioration of cardiac function. Other autoimmune abnormalities include infiltration of T cells in endomyocardial biopsies from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Additionally, the transfer of peripheral blood lymphocytes from DCM patients to severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice leads to ventricular remodeling [30]. In animal models, lymphocytes from rats with IHF can recognize and kill normal neonatal rat cardiac myocytes in vitro [31] and lead to autoimmune myocarditis in vivo after adoptive transfer [32].

Treg cells play a key role in the control of inflammation and autoimmune responses, and altered Treg cells predispose patients for uncontrolled immune activation or autoimmunity [3]. CHF patients were previously reported to have impaired Treg-cell number and function, but the precise mechanism behind this defect remains largely unknown [17]. In this study, we showed that reduced Treg cell number and function in CHF patients might be explained by impaired Treg-cell thymic output and increased apoptosis of these cell populations.

Like other T cells, Treg cells develop in the thymus [33]. A small fraction of Treg cells with a naïve CD45RA+CD45RO- surface profile (nTreg) has recently been detected in the circulation. However, this nTreg subset declines with age, as does thymic output and other naïve T cells [34]. By contrast, the majority of circulating Treg cells appear as a mature population with a memory CD45RA−CD45RO+ phenotype; these mTreg cells are stable throughout the life span, and the levels of mTreg cells increase during aging [35], [36]. nTreg cells could represent the de novo generation of thymic lymphocytes, so the assessment of nTreg cells is used to evaluate thymic Treg-cell production. In this study, we provided evidence that, in addition to decreased percentages of nTreg and mTreg cells, a shift from nTreg cells toward mTreg cells was evidenced by a reduced nTreg/mTreg cell ratio in CHF patients. This result indicated the possibility that impaired thymic export contributes to Treg cell defects in this patient population. However, nTreg cells can proliferate after thymic output while retaining their naïve phenotype [37]. CD31 has been used as a direct marker of thymic output and enabled the discrimination of recent thymic emigrant (RTE) Treg cells from peripherally expanded nTreg cells [38]. Thus, the assessment of nTreg cells co-expressing CD31 (RTE-Treg) is now used to evaluate the thymic output of Treg cells. The significant reduction of peripheral RTE-Treg cell content in CHF patients, when compared to the non-CHF controls, suggests a reduction of thymic Treg-cell output during the development of heart failure. An alternative approach to determine impaired Treg-cell thymic output in CHF patients was to assess intracellular concentration of TRECs in purified Treg cells. TRECs are generated during the process of T-cell receptor rearrangement in T-cell differentiation and do not duplicate during mitosis. TRECs are diluted out during homeostatic or antigen-driven T-cell proliferation in the periphery [18]. Therefore, TRECs are enriched in the newly synthesized and exported T-cell pool. nTreg cells, especially RTE-Treg cells, have higher frequencies of TRECs as compared with mTreg cells [38]. TREC content reduction in total Treg cells from CHF patients further supported our hypothesis that the Treg-cell output in the thymus of a CHF patient is functionally altered. Hass et al. recently reported that Treg cells from patients with and without multiple sclerosis showed different activities in suppressing T-effector cells. However, such differences disappeared after depleting the RTE-Treg cells, indicating a crucial role of RTE-Treg cells in the functional properties of the entire Treg population [38]. Thus, impaired thymus export of Treg cells could be associated not only with the number but also with the functional defect of Treg cells in CHF patients. Over the course of multiple sclerosis, for example, patients appear capable of amplifying mTreg-cell subpopulations to compensate for impaired thymic production of Treg cells [39]. In the case of CHF, in contrast, the homeostatic control of Treg cells seems to be disturbed. Both nTreg and mTreg cells were reduced in CHF patients (Figure 1D).

The homeostasis of Treg cells is maintained by a balance between Treg-cell generation and depletion. Apoptosis-induced alteration of Treg-cell levels has been associated with several diseases. For example, intrathyroidal CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases were prone to apoptosis, which led to a local Treg-cell reduction [40]. In contrast, patients with metastatic epithelial cancer demonstrated a significantly elevated proportion of peripheral Treg cells, and these cells were protected from apoptosis [41]. Apoptosis not only reduces the number of Treg cells, but also reduces their functions. By using T-effector cell suppression assays, Treg-cell apoptosis was closely associated with their capacity to inhibit T-effector cell proliferation [42]. In patients with type 1 diabetes, an increase in apoptosis was correlated with a decline in the suppressive potential of Treg cells [43]. As suggested by these studies, high sensitivity to IL-2 deprivation or FasL-induced apoptosis may contribute in part to the defect of Treg cells in CHF patients. Treg cells from CHF patients were more susceptible to apoptosis following IL-2 deprivation. Upon antigen activation, T cells induce the expression of CD95, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor/nerve growth factor receptor superfamily that induces apoptosis by binding to CD95L and subsequently activating caspase [44]. In the present study, we demonstrated that Treg cells in CHF patients had higher CD95 expression levels and were more sensitive to CD95/CD95L-mediated apoptosis than those in non-CHF subjects. Indeed, we also detected concurrent increases in serum soluble CD95L levels in CHF patients, consistent with prior observations [45]. These findings strongly suggest that the CD95/CD95L pathway is an important regulator of Treg-cell apoptosis in CHF patients.

After release from the thymus, Treg cells circulate continuously from blood to lymphoid tissues. In disease conditions, the expression of chemokine receptors, such as CCR4 and CCR8, on Treg cells allows their migration and recruitment to the site of inflammation [46]. In several human diseases, Treg cells preferentially accumulate at lymphoid tissues or sites of affected organs [47], [48]. Therefore, it is possible that decreases in peripheral Treg cells in CHF patients are caused by Treg-cell reallocation rather than an overall decrease. To investigate this possibility, we compared the Treg-cell numbers in the mediastinal lymph nodes or Foxp3 expression in cardiac biopsies between CHF patients and non-CHF controls. The results revealed that Treg-cell frequency in the mediastinal lymph nodes or Foxp3 expression in hearts of CHF patients was no higher than that of the non-CHF controls. However, this possibility could not be excluded due to the very small sample number. In addition to generation in the thymus, Treg cells can also be converted from activated effector or memory CD4+CD25− T cells in the periphery [49]. Peripherally converted Treg cells and thymus-generated Treg cells demonstrate a similar phenotype and suppressive functions. It is possible that such peripheral T-cell phenotype conversion was altered in CHF patients. This hypothesis merits further investigation.

TNF-α is central in the inflammatory cytokines response in CHF and play a role in the pathogenesis and clinical progression of the disease [50]. IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, may offer protection against TNF-α and an improvement in cardiac function in CHF has been associated with an increase in IL-10 [51] or a decrease in TNF-α/IL-10 ratio [52]. Our data indicated that Treg frequency was negatively correlated with serum level of TNF-α or the TNF-α/IL-10 ratio (Figure S1). In both our previous study [17] and the present study, we observed that total Treg number was significantly negatively correlated NT-proBNP which is considered as the most sensitive index of cardiac dysfunction in CHF patients. Based on these observations, we may speculate that Treg cells provided protection for the failing heart and defects in Treg cells is involved in the deterioration of cardiac function in CHF patients. However, the direct effect of Treg cells on cardiac dysfunction still needs to be studied in animal model.

IL-10 and TGF- β1 have been identified as the main effector cytokines of Treg cells [53]. We investigated the hypothesis that impaired Treg-cell function was associated with the decreased expression of these two cytokines. Disappointedly, we failed to observe a decrease in the expression of either IL-10 or TGF- β1 in CHF patients (Figure S2).

To conclude, our study revealed that both impaired export from the thymus and enhanced apoptosis can account for impaired Treg-cell number and function in CHF patients, offering a mechanistic explanation for the phenotypes and providing possible novel targets for CHF therapy through Treg-cell manipulation.

Materials and Methods

1. Subjects

samples were collected from 52 CHF patients (31 men and 21 women, 44±13 years old) and 43 non-CHF controls (28 men and 15 women, 42±12 years old). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Sigma, USA). Plasma was obtained after centrifugation and stored at −80°C. CHF diagnoses were based on clinical history, physical examination, echocardiography, chest X-ray, electrocardiography and levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), according to available guidelines pertaining to CHF. Patients were classified as having non-ischemic heart failure (NIHF) (n = 32, 17 men and 15 women) if they had no history of myocardial infarction and did not have significant coronary artery stenosis upon coronary angiography. Patients were considered to have ischemic heart failure (IHF) (n = 20, 14 men and 6 women) if the coronary angiography presented significant coronary artery disease (>50% stenosis in more than one major epicardial coronary artery) or the patients had a history of myocardial infarction or previous revascularization. Patients were excluded (1) if they were currently treated with anti-inflammatory drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids, (2) if they had collagen disease, thromboembolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation, advanced liver disease, renal failure, malignant disease, other inflammatory disease (such as septicemia, pneumonia), valvular heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or (3) if they had pacemakers. Patients with higher serum cholesterol than the target values after risk stratification [54], who received statin therapy within 3 months, were also excluded. Mediastinal lymph nodes [55] and left ventricular biopsies were obtained from six CHF patients (three patients with dilated cardiomyopathy who underwent cardiac transplantation and three patients with coronary heart disease who underwent the combined bypass surgery and left ventricular aneurysm resection) and three controls (heart graft donors without cardiomyopathy who died in car accidents).

2. Ethics statement

The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and patients and controls provided written informed consent.

3. Naïve Treg (nTreg), memory Treg (mTreg) and recent thymic emigrant-Treg (RTE-Treg) cells in the circulation

A 6-color flow cytometry analysis was performed to determine levels of nTreg, mTreg and RTE-Treg in the circulation. PBMCs were stained with surface antibodies for APC/Cy7 anti-human CD4, PE anti-human CD25, FITC anti-human CD45RA, Percp/Cy5.5 anti-human CD45RO and PE/Cy7 anti-human CD31 (Biolegend) for 30 min at 4°C. After surface staining, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with APC anti-human Foxp3, according to the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience, USA). Antibody isotype controls were performed to ensure antibody specificity. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with FACS Aria (BD Biosciences, USA).

4. Treg−cell isolation

A two-step selection using a CD4+CD25+CD127dim/− Regulatory T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) was used to isolate Treg cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, non-CD4+ and CD127high cells were magnetically labeled with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated antibodies and anti-biotin microbeads and subsequently depleted by negative selection. Pre-enriched CD4+ T cells were then labeled with anti-CD25 microbeads, and CD4+CD25+CD127dim/− Treg cells were isolated by positive selection. FACS was used to confirm the purity (>90%) of the isolated Treg cells.

5. Quantification of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs)

The Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA) was used to extract genomic DNA (gDNA) from purified Treg cells. Quantitative real-time PCR on an ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to determine the number of TRECs. Primer pairs and probes were as follows:

TREC: F: 5′-aacagcctttgggacactatcg-3′, R: 5′-gctgaacttattgcaactcgtgag-3′, probe: 5′-6FAM-ccacatccctttcaaccatgctgacacctc-TAMAR-3′;

RAG2: F: 5′-gcaacatgggaaatggaactg-3′, R: 5′-ggtgtcaaattcatcatcaccatc-3′, probe: 5′-6FAM-cccctggatcttctgttgatgtttgactgtttgtga-TRAMRA-3′. Data were expressed as TRECs/106 cells.

6. Apoptosis assays

Freshly isolated PBMCs were first stained with surface antibodies APC/Cy7 anti-human CD4, PE anti-human CD25, Percp/Cy5.5 anti-human CD95 (Fas) (Biolegend, USA) and Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-human CD127 (eBioscience, USA). Cells with the phenotype CD4+CD25+CD127low were identified as Treg cells. Apoptosis was measured using annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) co-staining (Bender MedSystems, USA). The proportion of annexin V+7-AAD− apoptotic cells in 7-AAD− viable Treg cells and the surface expression of CD95 on Treg cells were analyzed using FACS Aria (BD Biosciences, USA).

For IL-2 deprivation-mediated apoptosis, cells were stimulated with 2 µg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 (eBioscience, USA) and anti-human IL-2 monoclonal antibodies (Peprotech, 2 µg/ml) for 3 days. For Fas ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis, cells were stimulated with gradient concentrations of soluble recombinant FasL (Peprotech, USA) in complete RPMI1640 containing IL-2 (100 IU/ml) for 12 hrs [56]. CD4+CD25+CD127low/− Treg cells were also gated for annexin V+7-AAD– to determine apoptotic cell populations. Cell death was presented as (Percent of IL-2 deprivation- or FasL-mediated apoptosis - percent of apoptosis in the absence of anti-human IL-2 or FasL) / (100% - percent of cells in the absence of anti-human IL-2 or FasL)×100.

7. Soluble CD95 ligand (sCD95L) ELISA detection

Human FasL/TNFSF6 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, USA) was used to determine the plasma sCD95L levels. The minimal detectable concentration was 2.66 pg/ml, and intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <10%. All samples were measured in duplicate.

8. Treg-cell detection in mediastinal lymph node

Mediastinal lymph nodes were minced and filtered through a cell strainer to create a single cell suspension preparation. Lymphocytes were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque, stained with specific antibodies for CD4, CD25 and Foxp3, and subjected to FACS analysis. The number of Treg cells in the lymph nodes was quantified by flow cytometry.

9. Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol lysis buffer (Invitrogen, USA), and cDNA was prepared using the Revertra Ace® kit (Toyobo, Japan). Expression of target genes (Bcl-2 and Bak in purified Treg and Foxp3 cells) in heart tissues and lymphocytes isolated from mediastinal lymph nodes was quantified using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara, Japan) on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA). Primer pairs were as follows:

Bcl-2: F, 5-tacctgaaccggcacctg-3, R, 5-gccgtacagttccacaaagg-3;

Bak: F, 5-cctgccctctgcttctgag-3, R, 5-ctgctgatggcggtaaaaa-3;

Foxp3: F, 5′-gaaacagcacattcccagagttc-3′, R, 5′-atggcccagcggatgag-3′

GAPDH: F, 5′-ccacatcgctcagacaccat-3′, R, 5′-ggcaacaatatccactttaccagagt-3′

For each sample, the mRNA expression level was normalized to that of GAPDH. The mean of duplicate measurements was normalized and expressed as a ratio of target mRNA copies to GAPDH mRNA copies.

10. Quantification of transforming growth factor (TGF)-α and interleukin (IL)-10 expression in Treg cells

PBMCs were cultured in RPMI1640 containing 10% FBS and stimulated with PMA (50ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), ionomycin (1 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and monensin (1 µΜ, eBioscience, USA) for 4 h. Cells were stained with surface antibodies for APC/Cy7 anti-human CD4, PE anti-human CD25 (Biolegend, USA), Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-human CD127 (ebioscience, USA) for 30 min at 4°C. After surface staining, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with PE-cy7 anti-human TNF-α or PE-cy7 anti-human IL-10 (Biolegend, USA). Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with FACS Aria (BD Biosciences, USA).

11. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-10 ELISA detection

Commercial ELISA Kits (Invitrogen, USA) were used to determine the plasma TNF-α and IL-10 levels. The minimal detectable concentrations were 0.5 pg/ml and 0.78 pg/ml for TNF-α and IL-10 respectively. All samples were measured in duplicate.

12. Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or percentage in the text and figures. For variables with normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, independent t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test differences among two or more groups. For skewed variables, either non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test or Mann-Whitney U test were used for analyses. For the ranked data, Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test were used for the comparison between multiple groups. Spearman's correlation analysis was performed to determine correlation between the variables. In all cases, two-tailed, p<0.05 was considered significant.

Supporting Information

Correlation analysis between Treg frequency and plasma levels of cytokines in CHF patients (n = 20).

(TIF)

Comparison of intracellular IL-10 and TGF-β1 in CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg between CHF patients (n = 10) and healthy controls (n = 10).

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Li Yangqiu for providing the TREC plasmid. We also thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 30600234 and 30871067 to XC; 81070106 to XT); the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in the University of China (NCET-09-0380 to XC); the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2007CB512000 and 2007CB5 12005 to YHL; 2012CB517805 to YHL and XC); and the National Institutes of Health (USA) (HL60942, HL81090, and HL88547 to GPS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yndestad A, Damås JK, Oie E, Ueland T, Gullestad L, et al. Systemic inflammation in heart failure–the whys and wherefores. Heart Fail Rev. 2006;11:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s10741-006-9196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yndestad A, Holm AM, Müller F, Simonsen S, Frøland SS, et al. Enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines and activation markers in T-cells from patients with chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakaguchi S, Ono M, Setoguchi R, Yagi H, Hori S, et al. Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor A, Luboshits G, Planer D, Keren G, George J. Altered status of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2530–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng X, Yu X, Ding YJ, Fu QQ, Xie JJ, et al. The Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;971:9–19. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindley S, Dayan CM, Bishop A, Roep BO, Peakman M, et al. Defective suppressor function in CD4(+)CD25(+) T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:92–99. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrenstein MR, Evans JG, Singh A, Moore S, Warnes G, et al. Compromised function of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and reversal by anti-TNF alpha therapy. J Exp Med. 2004;200:277–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ait-Oufella H, Salomon BL, Potteaux S, Robertson AK, et al. Natural regulatory T cells control the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:178–180. doi: 10.1038/nm1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Fang L, Song S, Guo TB, Liu A, et al. Thymic regulation of autoimmune disease by accelerated differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells through IL-7 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2009;183:6135–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, et al. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1455–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan ME, Flierman R, van Duivenvoorde LM, Witteveen HJ, van Ewijk W, et al. Effective treatment of collagen-induced arthritis by adoptive transfer of CD25+ regulatory T cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2212–2221. doi: 10.1002/art.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling–concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frantz S, Bauersachs J, Ertl G. Post-infarct remodelling: contribution of wound healing and inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:474–481. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobaczewski M, Xia Y, Bujak M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. CCR5 signaling suppresses inflammation and reduces adverse remodeling after myocardial infarction-mediated recruitment of regulatory T cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2177–2187. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kvakan H, Kleinewietfeld M, Qadri F, Park JK, Fischer R, et al. Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Circulation. 2009;119:2904–2912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang TT, Ding YJ, Liao YH, Yu X, Xiao H, et al. Defective circulating CD4+CD25+Foxp3+CD127low regulatory T-cells in patients with chronic heart failure. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:451–458. doi: 10.1159/000303050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazenberg MD, Verschuren MC, Hamann D, Miedema F, van Dongen JJ. T cell receptor excision circles as markers for recent thymic emigrants: basic aspects, technical approach, and guidelines for interpretation. J Mol Med. 2001;79:631–640. doi: 10.1007/s001090100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FOXP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson BH. IL-2, regulatory T cells, and tolerance. J Immunol. 2004;172:3983–3988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, Salmon M, Poulter LW, et al. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1122::aid-immu1122>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krammer PH. CD95's deadly mission in the immune system. Nature. 2000;407:789–795. doi: 10.1038/35037728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fritzsching B, Oberle N, Eberhardt N, Quick S, Haas J, et al. In contrast to effector T cells, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are highly susceptible to CD95 ligand- but not to TCR-mediated cell death. J Immunol. 2005;175:32–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason JW. Myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: an inflammatory link. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caforio AL, Tona F, Bottaro S, Vinci A, Dequal G, et al. Clinical implications of anti-heart autoantibodies in myocarditis and dilated cardiomy opathy. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:35–45. doi: 10.1080/08916930701619235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teplliakov AT, Bolotskaia LA, Dibirov MM, Stepacheva TA, et al. Clinicoimmunological disorders in patients with postinfarction left ventricular remodeling and chronic cardiac failure. Ter Arkh. 2008;80:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Düngen HD, Platzeck M, Vollert J, Searle J, Müller C, et al. Autoantibodies against cardiac troponin I in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:668–675. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deubner N, Berliner D, Schlipp A, Gelbrich G, Caforio AL, et al. Etiology, Titre-Course, and Survival-Study Group. Cardiac beta1-adrenoceptor autoantibodies in human heart disease: rationale and design of the Etiology, Titre-Course, and Survival (ETiCS) Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:753–762. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omerovic E, Bollano E, Andersson B, Kujacic V, Schulze W, et al. Induction of cardiomyopathy in severe combined immunodeficiency mice by transfer of lymphocytes from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity. 2000;32:271–280. doi: 10.3109/08916930008994101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varda-Bloom N, Leor J, Ohad DG, Hasin Y, Amar M, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes are activated following myocardial infarction and can recognize and kill healthy myocytes in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2141–2149. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maisel A, Cesario D, Baird S, Rehman J, Haghighi P, et al. Experimental autoimmune myocarditis produced by adoptive transfer of splenocytes after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 1998;82:458–463. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Josefowicz SZ, Rudensky A. Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity. 2009;30:616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valmori D, Merlo A, Souleimanian NE, Hesdorffer CS, Ayyoub M. A peripheral circulating compartment of natural naive CD4 Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1953–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI23963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Zhang Y, Cook JE, Fletcher JM, McQuaid A, et al. Human CD4+ CD25hi Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are derived by rapid turnover of memory populations in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2423–2433. doi: 10.1172/JCI28941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregg R, Smith CM, Clark FJ, Dunnion D, Khan N, et al. The number of human peripheral blood CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells increases with age. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akbar AN, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Taams LS, Macallan DC. The dynamic co-evolution of memory and regulatory CD4+ T cells in the periphery. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:231–7. doi: 10.1038/nri2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas J, Fritzsching B, Trübswetter P, Korporal M, Milkova L, et al. Prevalence of newly generated naïve regulatory T cells (Treg) is critical for Treg suppressive function and determines Treg dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2007;179:1322–1330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venken K, Hellings N, Broekmans T, Hensen K, Rummens JL, et al. Natural naive CD4+CD25+CD127low regulatory T cell (Treg) development and function are disturbed in multiple sclerosis patients: recovery of memory Treg homeostasis during disease progression. J Immunol. 2008;180:6411–6420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakano A, Watanabe M, Iida T, Kuroda S, Matsuzuka F, et al. Apoptosis-induced decrease of intrathyroidal CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in autoimmune thyroid diseases. Thyroid. 2007;17:25–31. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanzer S, Dandachi N, Balic M, Resel M, Samonigg H, et al. Resistance to apoptosis and expansion of regulatory T cells in relation to the detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic epithelial cancer. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:107–114. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fritzsching B, Korporal M, Haas J, Krammer PH, Suri-Payer E, et al. Similar sensitivity of regulatory T cells towards CD95L-mediated apoptosis in patients with multiple sclerosis and healthy individuals. J Neurol Sci. 2006;251:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glisic-Milosavljevic S, Waukau J, Jailwala P, Jana S, Khoo HJ, et al. At-risk and recent-onset type 1 diabetic subjects have increased apoptosis in the CD4+CD25+ T-cell fraction. PLoS One. 2007;2:e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu G, Shi Y. Apoptosis signaling pathways and lymphocyte homeostasis. Cell Res. 2007;17:759–771. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi S, Yamaoka M, Okuyama M, Nitoube J, Fukui A, et al. Elevated circulating levels and cardiac secretion of soluble Fas ligand in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1500–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei S, Kryczek I, Zou W. Regulatory T-cell compartmentalization and trafficking. Blood. 2006;108:426–431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hesse M, Piccirillo CA, Belkaid Y, Prufer J, Mentink-Kane M, et al. The pathogenesis of schistosomiasis is controlled by cooperating IL-10-producing innate effector and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3157–3166. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suvas S, Azkur AK, Kim BS, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control the severity of viral immunoinflammatory lesions. J Immunol. 2004;172:4123–4132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang S, Alard P, Zhao Y, Parnell S, Clark SL, et al. Conversion of CD4+ CD25- cells into CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo requires B7 costimulation, but not the thymus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:127–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleinbongard P, Schulz R, Heusch G. TNFα in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, remodeling and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16(1):49–69. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adamopoulos S, Parissis JT, Paraskevaidis I, et al. Effects of growth hormone on circulating cytokine network, and left ventricular contractile performance and geometry in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(24):2186–96. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stumpf C, Lehner C, Yilmaz A, Daniel WG, Garlichs CD. Decrease of serum levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;105(1):45–50. doi: 10.1042/CS20020359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Askenasy N, Kaminitz A, Yarkoni S. Mechanisms of T regulatory cell function. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(5):370–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joint committee for developing Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults. Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults. Chin J Cardiol. 2007;35:390–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luppi P, Rudert WA, Zanone MM, Stassi G, Trucco G, et al. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a superantigen-driven autoimmune disease. Circulation. 1998;98:777–785. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.8.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Badoual C, Dorgham K, et al. Global natural regulatory T cell depletion in active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2005;175:8392–8400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation analysis between Treg frequency and plasma levels of cytokines in CHF patients (n = 20).

(TIF)

Comparison of intracellular IL-10 and TGF-β1 in CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg between CHF patients (n = 10) and healthy controls (n = 10).

(TIF)