Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a severe neuropsychiatric disorder which has complex pathobiology with profound influences of genetic factors in its development. Although the numerous autism susceptible genes were identified, the etiology of autism is not fully explained. Using DNA microarray, we examined gene expression profiling in peripheral blood from 21 individuals in each of the four groups; young adults with ASD, age- and gender-matched healthy subjects (ASD control), healthy mothers having children with ASD (asdMO), and asdMO control. There was no blood relationship between ASD and asdMO. Comparing the ASD group with control, 19 genes were found to be significantly changed. These genes were mainly involved in cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, and nerve system development and function. In addition, the asdMO group possessed a unique gene expression signature shown as significant alterations of protein synthesis despite of their nonautistic diagnostic status. Moreover, an ASD-associated gene expression signature was commonly observed in both individuals with ASD and asdMO. This unique gene expression profiling detected in peripheral leukocytes from affected subjects with ASD and unaffected mothers having ASD children suggest that a genetic predisposition to ASD may be detectable even in peripheral cells. Altered expression of several autism candidate genes such as FMR-1 and MECP2, could be detected in leukocytes. Taken together, these findings suggest that the ASD-associated genes identified in leukocytes are informative to explore the genetic, epigenetic, and environmental background of ASD and might become potential tools to assess the crucial factors related to the clinical onset of the disorder.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication, and restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests. Several twin studies have consistently demonstrated a higher concordance for monozygotic than dizygotic twins [1], [2], [3], [4]. Family studies have shown a marked increase in the occurrence rate of autism and milder phenotypes with subtle communication/social impairments or stereotypic behaviors among the relatives of autistic individuals compared with those of controls [5], [6]. Considering such evidence for familial aggregation of autism phenotypes with various degrees, multiple susceptibility factors, including genetic factors, are considered to be involved in the clinical manifestation of autism spectrum, interacting in complex ways with experiential factors during developmental courses [7].

The susceptibility genes to ASD remain largely unknown yet; however, recent molecular genomic approaches suggest that abnormal synaptic homeostasis represents a risk factor for ASD. For example, ASD-associated genes include glutamate receptors, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, neuroligins (NLGNs), neurexin 1, SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 3 (SHANK3), which are involved in synapse formation and function [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Several genes that are essential for neurological development, such as roundabout, axon guidance receptor, homolog 1 (ROBO1) and early growth response 2 (EGR2) are also differentially expressed in the lympnoblastoid cell lines from monozygotic twins discordant in severity of autism spectrum [13]. Neuronal differentiation- and survival-associated genes, such as wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (WNT2) and homeobox A1 (HOXA1) were also reported as autism susceptibility genes [14], [15]. A large-scale single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association analysis involving 1,168 multiplex families revealed a single region on chromosome 11p12-p13 that exceeded the threshold for suggestive linkage as autism risk loci [16]. Recently, analysis in human postmortem cortical tissues from ASD cases has shown the association between a SNP in the promoter of the met proto-oncogene (MET) gene and a risk for ASD [17], [18]. This gene encodes the MET receptor tyrosine kinase and contributes to development of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum, which process may be disrupted in autism. Voineagu et. al. have reported that analysis of postmortem brain tissue samples from autism cases showed the splicing dysregulation and altered gene expression involved in neuronal and synaptic signaling dysfunction in the ASD brain [19].

Multiple susceptible factors are likely to influence directly or indirectly gene expression, resulting in functional alterations in proteins regulating synaptic homeostasis. The altered gene expression could be detected as gene expression signatures unique to ASD even in peripheral tissues. Increasing molecular genomic studies have indicated the importance of differential expression of ASD-associated genes in peripheral tissues as well as postmortem brains from subjects with ASD [13], [20], [21]. For example, gene expression profiling of lymphoblastoid cell lines are well-studied because of their characteristically homogeneity. These findings led us to speculate that ASD-associated changes in gene expression could be detectable in peripheral blood leucocytes from individuals with ASD.

In addition, identification of genetic etiology of ASD is hampered by the heterogeneity of autism phenotypes. One way of explaining this heterogeneity is broadening studies beyond the strict diagnosis of autism, by doing this, it may determine which components of the autistic symptoms are genetically transmitted and how these components interact [7]. To prove this hypothesis, we examined gene expression in peripheral blood from subjects with ASD and healthy mothers having children with ASD, and found an ASD-associated gene expression signature commonly observed in both individuals with ASD and healthy mothers having children with ASD, between whom there was no blood relationship. These findings may provide novel information for understanding the genetic background of ASD.

Methods

Study Subjects

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (NCNP), Japan and by the Human Study Committee of the Tokushima University Hospital, Japan. After the experimental procedures were fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from each parent of minor subject and participants himself/herself, or from each adult subject. Adolescents and adults with ASD (17 males and 4 females; aged 26.7±5.5 y (mean±SD), range 18–38 y, n = 21) and the healthy women who had children with ASD (asdMO; 44.7±6.7 y, range 33–58 y, n = 21) were recruited from our research volunteer pool or specialized clinics and enrolled as the ASD group and the asdMO group, respectively. Subjects of the ASD group and those of asdMO group were biologically unrelated each other. The pre-existing clinical diagnoses of ASD were confirmed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association, 2000) based on clinical interviews with subjects and/or parents using semi-structured interviews that were validated for Japanese pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) populations [22] by our research team including experienced child psychiatrist and developmental pediatrician. To corroborate the ASD diagnosis, the Japanese version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ-J) [23], [24] were completed by themselves and those scores except 3 subjects were above the cut-off of 26 (Table 1). Intellectual functions of the ASD subjects were evaluated using Japanese versions of WAIS-III: all ASD subjects exhibited normal IQ (mean full scale IQ; 91.86±21.62) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the ASD and asdMO groups.

| ID | gender | age | AQ score | WAIS | ||

| ASD (n = 21) | SUM | VIQ | PIQ | FIQ | ||

| 1 | M | 18 | 34 | 126 | 109 | 122 |

| 2 | M | 18 | 30 | 91 | 92 | 91 |

| 3 | M | 20 | . | 67 | 82 | 71 |

| 4 | M | 20 | 32 | 88 | 61 | 72 |

| 5 | M | 22 | 31 | 70 | 54 | 60 |

| 6 | M | 23 | . | 59 | 62 | 54 |

| 7 | M | 24 | 30 | 109 | 95 | 104 |

| 8 | M | 24 | 31 | 106 | 91 | 100 |

| 9 | M | 26 | 36 | 88 | 70 | 78 |

| 10 | M | 26 | 30 | 72 | 75 | 71 |

| 11 | M | 27 | 31 | 103 | 84 | 94 |

| 12 | M | 28 | 28 | 98 | 64 | 82 |

| 13 | M | 29 | . | 77 | 83 | 78 |

| 14 | M | 29 | 32 | 114 | 128 | 121 |

| 15 | M | 32 | 24 | 132 | 115 | 127 |

| 16 | M | 34 | 21 | 108 | 106 | 107 |

| 17 | M | 38 | 29 | 92 | 64 | 78 |

| 18 | F | 27 | 19 | 111 | 102 | 108 |

| 19 | F | 28 | 37 | 85 | 78 | 80 |

| 20 | F | 32 | 30 | 119 | 110 | 117 |

| 21 | F | 35 | 39 | 105 | 112 | 114 |

| mean±SD | 26.67±5.53 y | 30.22±5.06 | 96.19±19.92 | 87.48±21.62 | 91.86±21.62 | |

| asdMO (n = 21) | ||||||

| 1 | F | 33 | . | . | . | . |

| 2 | F | 36 | . | . | . | . |

| 3 | F | 37 | . | . | . | . |

| 4 | F | 39 | . | . | . | . |

| 5 | F | 39 | . | . | . | . |

| 6 | F | 41 | . | . | . | . |

| 7 | F | 41 | . | . | . | . |

| 8 | F | 41 | . | . | . | . |

| 9 | F | 42 | . | . | . | . |

| 10 | F | 44 | . | . | . | . |

| 11 | F | 46 | . | . | . | . |

| 12 | F | 46 | . | . | . | . |

| 13 | F | 47 | . | . | . | . |

| 14 | F | 47 | . | . | . | . |

| 15 | F | 49 | . | . | . | . |

| 16 | F | 49 | . | . | . | . |

| 17 | F | 50 | . | . | . | . |

| 18 | F | 51 | . | . | . | . |

| 19 | F | 51 | . | . | . | . |

| 20 | F | 58 | . | . | . | . |

| 21 | F | 58 | . | . | . | . |

| mean±SD | 44.73±6.66 y | |||||

IQ = Intelligence Quotients; VIQ = Verbal IQ; PIQ = Performance IQ; FIQ = Full IQ; AQ = Autism-Spectrum Quotient; M = Male; F = Female; y = year.

Additionally, age- and sex-matched healthy volunteers were recruited from students or staffs of the Faculty of Medicine, the University of Tokushima and NCNP, and the local communities, and enrolled as controls for the ASD group (Control group; aged 27.0±5.5 y, range 19–39 y, n = 21) or controls for asdMO group (ctrlMO group; aged 44.7±6.7 y, range 31–59 y, n = 21). We confirmed that they did not have any serious physical or mental disorders including ASD in the past and at present, the children of the ctrlMO group have not been diagnosed as ASD and were in good health by interviews. All control subjects had not been medicated at least for three months prior to the recruitment.

RNA preparation, amplification, and hybridization

Venous blood (5 ml) was taken from each subject and immediately poured into PAXgeneTM blood RNA tubes (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA was purified using a PAXgene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacture's protocol. Contaminated DNA was removed using a DNase kit (Qiagen). The quality of the purified RNA and its applicability for microarray analysis were assessed by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using a RNA 6000 Nano Labchip kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). High quality RNA with a RIN number above 8.0 was used for microarray analysis and quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qPCR). For microarray analysis, total RNA (400 ng) was used for amplification and labeling of complementary RNA (cRNA) using a Low RNA Input Linear Amplification Kit PLUS and a succinimide-containing fluorescent dye (Cy3)-CTP according to the manufacturer's protocol (Agilent). Cy3-labeled cRNA was applied to the whole human genome oligoDNA microarray (4×44 k; Agilent) following the manufacturer's protocol. Hybridization was performed at 65°C for 17 h. After washing, fluorescence intensity at each spot was measured using a G2565BA Microarray Scanner (Agilent). Table S1 summarizes the array design and profile of subjects that were analyzed in this study.

Microarray analysis

Signal intensities of Cy3 were quantified and analyzed by subtracting backgrounds using Feature Extraction 10 software (Agilent). Raw data output was imported into Genespring GX10 (Agilent) and normalized each chip to the 75th percentile of all measurements (per chip normalization), and normalized each probe to the median expression of matched control intensity for that gene across all samples (per gene normalization). Following normalization, we filtered genes having fluorescence intensities higher than a cutoff value of 50 among all samples.

Pathway and functional analyses

The data sets of differentially expressed genes between the ASD and Control group, and the asdMO and ctrlMO group were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) application (Ingenuity Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA). IPA was used to identify molecular and cellular processes, biological functions, and modules of functionally related genes modified by the genes identified as significantly differentially expressed. IPA utilizes the knowledge in the literature about biological interactions among genes and proteins. The probability of a relationship between each biological function and the identified genes was calculated by Fisher's exact tests. The level of significance was set at p-value of 0.05. A detailed description is given in the online repository (http://www.ingenuity.com).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qPCR) analysis

qPCR was done to validate the results obtained by the oligoDNA microarray. Total RNA (400 ng) from each sample was reverse transcribed with oligo dT primer and SuperScript™ III (invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR reaction was performed with synthesized cDNA using the ABI-PRISM 7500 sequence detection system and TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacture's protocols. For measurement of quantitative gene expression levels, we purchased oligonucleotide primers and gene-specific TaqMan probes from Applied Biosystems (Table S2). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and histone deacetylase 1(HDAC1) were used as endogenous quantity controls. Data were analyzed using SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems). Quantity values were normalized by GAPDH or HDAC1 mRNA levels. After the relative ratios of each mRNA expression level between the ASD and Control group, and the asdMO and ctrlMO group were calculated, the unpaired t tests were used to compare the relative ratios for each mRNA for two pairs.

Results

Altered gene expression in peripheral blood in the ASD group

First, we examined differentially expressed genes in peripheral leukocytes between 21 subjects with ASD and their age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Microarray measurement showed that 19,194 probes in total had fluorescence intensities higher than a cut-off value of 50 among all samples. Unpaired t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons at the 0.05 false discovery rate (FDR) selected 9,784 probes that were differentially expressed between the ASD and Control groups. The raw and normalized values for all samples by microarray analysis were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number: GSE26415). When the fold-change criterion was set at > 2-fold in the mean expression level, 28 probes passed the criterion and corresponded to 19 annotated genes. Among them, 18 genes (NOVA2, SLC22A18AS, C21orf58, LZTR2, RKHD1, BC018095, FAM124A, LHB, TAOK2, UBL4A, ITGA2B, PLCXD2, NRN1, KLHDC7A, MYOG, NUMBL, WDTC2, and SDK2) were significantly up-regulated, while one gene (UTS2) was down-regulated in the ASD group. These transcripts are listed according to greatest fold change in expression in Table 2.

Table 2. Differentially expressed genes for the ASD group compared with the Control group.

| Accession No. | GeneSymbol | Description | fold change | corrected p-value |

| Up-regulated gene | ||||

| NM_002516 | NOVA2 | neuro-oncological ventral antigen 2 | 2.34 | 8.23E-03 |

| NM_007105 | SLC22A18AS | solute carrier family 22 (organic cation transporter), member 18 antisense | 2.29 | 4.06E-03 |

| NM_199071 | C21ORF58 | chromosome 21 open reading frame 58 | 2.25 | 4.19E-03 |

| BC009106 | LZTR2 (SEC16B) | leucine zipper transcription regulator 2 | 2.22 | 7.49E-03 |

| NM_203304 | RKHD1 (MEX3D) | ring finger and KH domain containing 1 | 2.22 | 4.27E-03 |

| BC018095 | BC018095 | hypothetical protein LOC441869 | 2.21 | 6.92E-03 |

| NM_145019 | FAM124A | family with sequence similarity 124A | 2.14 | 4.07E-03 |

| NM_000894 | LHB | luteinizing hormone beta polypeptide | 2.13 | 1.09E-02 |

| NM_016151 | TAOK2 | TAO kinase 2 | 2.13 | 1.03E-02 |

| NM_014235 | UBL4A | ubiquitin-like 4A | 2.12 | 9.31E-03 |

| NM_000419 | ITGA2B | integrin, alpha 2b (platelet glycoprotein IIb of IIb/IIIa complex, antigen CD41) | 2.12 | 4.90E-04 |

| NM_153268 | PLCXD2 | phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, X domain containing 2 | 2.12 | 7.29E-03 |

| NM_016588 | NRN1 | neuritin 1 | 2.10 | 4.90E-03 |

| NM_152375 | KLHDC7A | kelch domain containing 7A | 2.08 | 1.37E-02 |

| NM_002479 | MYOG | myogenin (myogenic factor 4) | 2.07 | 1.06E-02 |

| NM_004756 | NUMBL | numb homolog (Drosophila)-like | 2.03 | 1.19E-02 |

| NM_015023 | WDTC1 | WD and tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 2.03 | 1.27E-02 |

| NM_019064 | SDK2 | Homo sapiens sidekick homolog 2 (chicken) | 2.01 | 4.70E-03 |

| Down-regulated gene | ||||

| NM_021995 | UTS2 | urotensin 2 | −4.25 | 1.67E-03 |

*corrected p-value was calculated by unpaired t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons at the 0.05 false discovery rate (FDR).

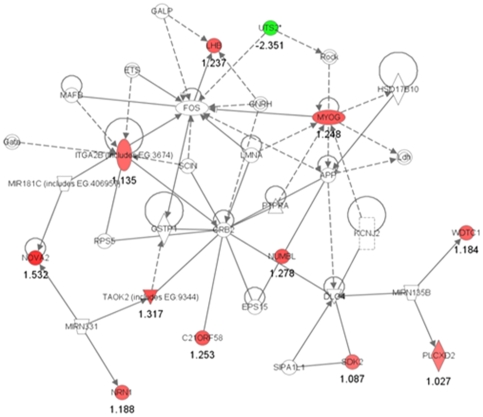

The 19 differentially expressed genes were then subjected to the biofunctional pathway analysis using IPA. The net work analysis ranked “cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, nerve system development and function” as the top-scoring net work (Figure 1). Particularly, 12 (C21ORF58, ITGA2B, LHB, MYOG, NOVA2, NRN1, NUMBL, PLCXD2, SDK2, TAOK2, UTS2 and WDTC1) out of the 19 genes were included in this network. The molecules encoded by 11 up- or 1 down-regulated genes are shown in red and green in this network, respectively (Figure 1). The network analysis picked up several other networks, but only one or two genes were included in those networks. The top-scored biofunctions modified by the 19 genes significantly (p<0.05 by Fisher's exact test) were 1) cardiovascular disease (p-value: 3.46E-04), 2) vitamin and mineral metabolism (7.08E-04), 3) cell signaling (7.08E-04), 4) cellular development (9.90E-04), and 5) genetic disorder (9.90E-04). Although we examined the probability of a relationship between the identified 19 genes and each canonical pathway, IPA did not show any significantly modified pathway with p value of <0.01.

Figure 1. Ingenuity pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes for the ASD group compared with the Control group.

The top scored network using the 19 differentially expressed genes for the ASD group (> 2-fold vs. control) is “cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, nerve system development and function”, with 12 focus molecules and a score of 31. The network is displayed graphically as nodes (gene) and edges (the biological relationship between genes). The color intensity indicates the genes up-regulated or down-regulated in ASD are shown in red or green, respectively. The mean of log2 expression values compared with the Control group are described as logarithm scale.

Differentially expressed genes in the asdMO group

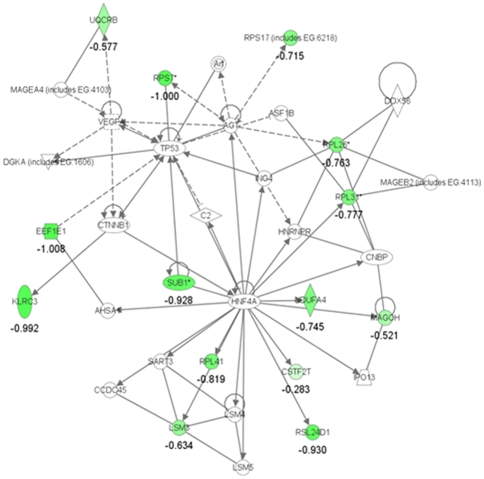

Using a similar way to that mentioned above for the ASD group, 57 annotated genes from 176 probes were identified to be differentially expressed in the asdMO group compared with the ctrlMO group (Table 3). The 57 genes were composed of 17 up-regulated and 40 down-regulated genes in the asdMO group. Analysis of the 57 genes with IPA indicated that “cancer, RNA post-transcriptional modification and reproductive system disease” was ranked as the top network in which 14 down-regulated genes were involved (Figure 2). The 57 genes significantly changed 57 biofunctional pathways in total. The most remarkable change was observed in the function of protein synthesis (p-value = 2.48E-08). Particularly, 10 genes encoding ribosomal proteins (RPL7, RPL26, RPL31, RPL34, RPL39, RPL41, RPL9, RPS17, RPS27L, and RPS3A) were significantly down-regulated in the asdMO group. Furthermore, several down-regulated (CD69, TNFRSF17, and BCL2A1) and up-regulated (KRT1 and C4B) were involved in several immune functions, such as antigen presentation (p-value = 1.95E-07), cell-mediated immune response (p-value = 1.49E-05), and humoral immune response (p-value = 1.49E-05). As for the canonical pathway analysis, IPA did not reveal any significantly pathway modified by the 57 genes.

Table 3. Differentially expressed genes for the asdMO group compared with the ctrlMO group.

| Accession No. | GeneSymbol | Description | fold change | corrected p-value |

| Up-regulated gene | ||||

| AK024445 | C14ORF56 | chromosome 14 open reading frame 56 | 2.85 | 1.16E-03 |

| NM_020478 | ANK1 | ankyrin 1, erythrocytic | 2.73 | 1.32E-03 |

| NM_015431 | TRIM58 | tripartite motif-containing 58 | 2.66 | 3.81E-03 |

| NM_138368 | DKFZP761E198 | DKFZp761E198 protein | 2.54 | 2.40E-03 |

| BC009106 | LZTR2 (SEC16B) | SEC16 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) | 2.33 | 4.54E-02 |

| NM_000419 | ITGA2B | integrin, alpha 2b (platelet glycoprotein IIb of IIb/IIIa complex, antigen CD41) | 2.29 | 6.45E-03 |

| NM_001266 | CES1 | carboxylesterase 1 (monocyte/macrophage serine esterase 1) | 2.23 | 5.81E-03 |

| NM_001002029 | C4B | complement component 4B (Chido blood group) | 2.21 | 2.46E-02 |

| NM_001001957 | OR2W3 | olfactory receptor, family 2, subfamily W, member 3 | 2.15 | 1.50E-02 |

| NM_000894 | LHB | luteinizing hormone beta polypeptide | 2.15 | 4.37E-02 |

| NM_006121 | KRT1 | keratin 1 | 2.13 | 1.67E-02 |

| NM_002501 | NFIX | nuclear factor I/X (CCAAT-binding transcription factor) | 2.09 | 3.31E-03 |

| NM_001039476 | NPRL3 (C16ORF35) | nitrogen permease regulator-like 3 (S. cerevisiae) | 2.06 | 4.84E-03 |

| NM_006798 | UGT2A1 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide A1 | 2.06 | 2.74E-02 |

| NM_001024858 | SPTB | spectrin, beta, erythrocytic | 2.05 | 4.05E-03 |

| NM_198149 | SHISA4 | shisa homolog 4 (Xenopus laevis) | 2.02 | 1.20E-02 |

| NM_007371 | BRD3 | bromodomain containing 3 | 2.02 | 1.11E-03 |

| Down-regulated gene | ||||

| NM_002624 | PFDN5 | prefoldin subunit 5 | −2.00 | 7.37E-03 |

| NM_012459 | TIMM8B | translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 8 homolog B (yeast) | −2.01 | 8.93E-04 |

| NM_014463 | LSM3 | LSM3 homolog, U6 small nuclear RNA associated (S. cerevisiae) | −2.01 | 1.59E-03 |

| AB075859 | ZNF525 | zinc finger protein 525 | −2.01 | 2.31E-03 |

| NM_002489 | NDUFA4 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 4, 9kDa | −2.02 | 2.77E-03 |

| NM_001803 | CD52 | CD52 molecule | −2.03 | 2.58E-03 |

| NM_001019 | RPS15A | ribosomal protein S15a | −2.03 | 3.73E-03 |

| NM_005034 | POLR2K | polymerase (RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide K, 7.0kDa | −2.05 | 2.56E-03 |

| NM_001021 | RPS17 | ribosomal protein S17 | −2.06 | 4.70E-03 |

| NM_021104 | RPL41 | ribosomal protein L41 | −2.09 | 6.64E-03 |

| NM_001781 | CD69 | CD69 molecule | −2.09 | 4.54E-03 |

| NM_005340 | HINT1 | histidine triad nucleotide binding protein 1 | −2.12 | 1.96E-03 |

| NM_000971 | RPL7 | ribosomal protein L7 | −2.12 | 4.29E-03 |

| NM_007333 | KLRC3 | killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 3 | −2.12 | 6.86E-03 |

| NM_016304 | RSL24D1 (C15orf15) | ribosomal L24 domain containing 1 | −2.12 | 5.56E-03 |

| NM_203495 | COMMD6 | COMM domain containing 6 | −2.15 | 5.13E-03 |

| NM_015920 | RPS27L | ribosomal protein S27-like | −2.17 | 2.01E-03 |

| NM_019051 | MRPL50 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L50 | −2.18 | 1.16E-03 |

| NM_001026 | RPS24 | ribosomal protein S24 | −2.18 | 2.80E-03 |

| NM_002370 | MAGOH | mago-nashi homolog, proliferation-associated (Drosophila) | −2.19 | 5.86E-04 |

| NM_001192 | TNFRSF17 | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 17 | −2.23 | 1.83E-02 |

| NM_005213 | CSTA | cystatin A (stefin A) | −2.23 | 1.70E-03 |

| NM_002586 | PBX2 | pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox 2 | −2.27 | 3.17E-03 |

| NM_000987 | RPL26 | ribosomal protein L26 | −2.27 | 6.54E-03 |

| NM_003096 | SNRPG | small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide G | −2.30 | 2.26E-03 |

| NM_004049 | BCL2A1 | BCL2-related protein A1 | −2.32 | 4.72E-03 |

| NM_001000 | RPL39 | ribosomal protein L39 | −2.34 | 2.94E-03 |

| NM_006294 | UQCRB | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase binding protein | −2.34 | 2.79E-03 |

| NM_000985 | RPL17 | ribosomal protein L17 | −2.37 | 1.61E-03 |

| NM_016093 | RPL26L1 | ribosomal protein L26-like 1 | −2.37 | 2.28E-03 |

| NM_015235 | CSTF2T | cleavage stimulation factor, 3′ pre-RNA, subunit 2, 64kDa, tau variant | −2.41 | 1.80E-03 |

| NM_000661 | RPL9 | ribosomal protein L9 | −2.47 | 1.82E-03 |

| NM_004280 | EEF1E1 | eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 epsilon 1 | −2.49 | 8.51E-04 |

| NM_005127 | CLEC2B | C-type lectin domain family 2, member B | −2.53 | 1.45E-03 |

| NM_000993 | RPL31 | ribosomal protein L31 | −2.57 | 3.59E-03 |

| NM_006713 | SUB1 | SUB1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | −2.59 | 2.15E-03 |

| NM_001011 | RPS7 | ribosomal protein S7 | −2.59 | 1.70E-03 |

| NM_033625 | RPL34 | ribosomal protein L34 | −2.64 | 3.73E-03 |

| BC049823 | RPL22L1 | ribosomal protein L22-like 1 | −2.84 | 1.16E-03 |

| NM_001006 | RPS3A | ribosomal protein S3A | −3.08 | 1.64E-03 |

*corrected p-value was calculated by unpaired t test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons at the 0.05 FDR.

Figure 2. Ingenuity pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes for the asdMO group compared with the ctrlMO group.

The top scored network using the 57 genes identified as differentially expressed genes for the asdMO group (> 2-fold vs. ctrlMO) is “cancer, RNA post-transcriptional modification, reproductive system disease”, with 14 focus molecules and a score of 27. The color intensity indicates the genes up-regulated or down-regulated in asdMO are shown in red or green, respectively. The mean of log2 expression values compared with the ctrlMO group are described as logarithm scale.

Similarity in gene expression profiling between the ASD and asdMO group

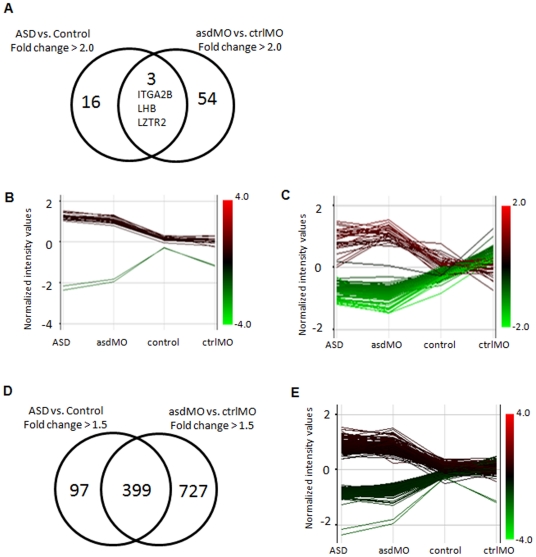

As described above, we identified 19 differentially expressed genes in young subjects with ASD compared their age- and sex-matched controls, and 57 differentially expressed genes comparing healthy women with and without ASD children. Among the 19 and 57 genes which were separately identified according to our 2-fold change criterion by two comparisons, three genes (ITGA2B, LHB, and LZTR2) overlapped (Figure 3A). It should be noted that expression of the 19 genes (Figure 3B) and the 57 genes (Figure 3C) changed in a parallel direction between the ASD and asdMO group, indicating that healthy women having ASD children shared some gene expression signature in common with individuals diagnosed as ASD, although they had no full symptoms above clinical threshold of ASD. When the fold change criterion was lowered from > 2.0 to > 1.5, 496 differentially expressed genes were identified in the ASD group compared with the Control group. In this case, 399 out of 496 genes were also included in 1126 genes differentially expressed in the asdMO group compared with the ctrlMO group by a looser cutoff of 1.5-fold change (Figure 3D), and the altered direction of 399 genes was similar between the ASD and asdMO group (Figure 3E). The 399 overlapping genes are listed in Table S3. We also examined a pathway or functional analysis of the 399 genes. As shown in Table 4, the network analysis ranked “Nervous System Development and Function, Tissue Development, Genetic Disorder” as the top-scoring net work. Subsequently, the overlapping gene set modified “Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Tissue Development, Embryonic Development” and “Gene Expression, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Hematological System Development and Function”. The top-scored biofunctions modified by the overlapping genes were 1) Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction (p-value: 5.86E-06), 2) Reproductive System Development and Function (5.86E-06), 3) Tissue Development (5.86E-06). These results indicated that some genetic predisposition of ASD specifically found in the ASD group was also shared by only healthy women having ASD children, but not healthy women having non-ASD children or healthy adults, which could be detectable as an ASD-associated gene expression signature in peripheral leukocytes.

Figure 3. Similarity in gene expression profiling between the ASD and asdMO group.

Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes for the ASD group compared with the Control group and the asdMO group compared with the ctrlMO group (> 2-fold change) (A). RNA was prepared from each group and subjected to microarray analysis. Differentially expressed 19 and 57 genes by >2-fold in ASD group and asdMO group, respectively. Three genes were overlapped. The mean of expression values of the 19 genes (B) and the 57 genes (C) changed in a parallel direction between the ASD and asdMO group. The normalized intensity value of genes, which was up-regulated or down-regulated by 2-fold, is shown in red or green, respectively, compared with control or ctrlMO. Venn diagram of differentially expressed 496 and 1126 genes by >1.5-fold in ASD group and asdMO group (D). 399 genes were overlapped. The mean of expression values of the overlapped 399 genes was similar direction between the ASD and asdMO group (E). The normalized intensity value of genes, which was up-regulated or down-regulated by 1.5-fold, is shown in red or green, compared with control.

Table 4. Biological roles of overlapping genes (>1.5-fold change) between ASD and asdMO group.

| A) Associated Network Functions for overlapping genes | ||

| score | ||

| Nervous System Development and Function, Tissue Development, Genetic Disorder | 40 | |

| Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Tissue Development, Embryonic Development | 36 | |

| Gene Expression, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Hematological System Development and Function | 34 |

Confirmation by qPCR

Based on the microarray data, we selected putative ASD-associated genes (16 out of the 19 ASD-associated genes identified by comparison between the ASD and Control group, and 19 out of 57 asdMO-associated genes by comparison between the asdMO and ctrlMO group, shown in Table 5) and validated changes in their expression levels using qPCR. Among the 19 ASD-associated genes, three mRNA levels (C21orf58, SDK2, and BC018095) could not be measured, since appropriate TaqMan gene probes for them were not available. Among the 57 asdMO-associated genes, we preferentially selected a group of genes encoding key molecules in the regulation of the top-scoring biological function (protein synthesis). GAPDH mRNA levels were used as an internal control. In addition, we measured HDAC1 mRNA levels as another internal quantity control, since the microarray measurement showed constant expression levels of these two mRNAs among all subjects, which were also confirmed by qPCR. The result using GAPDH as an internal control was similar to that using HDAC1 instead (data not shown).

Table 5. Real-time qPCR validation of ASD-related/asdMO-related gene expression levels (relative mRNA expression to GAPDH).

| Control | ASD | ctrlMO | asdMO | p-value | ||

| Gene | relative expression | expression value | expression value | expression value | ||

| mean±SEM | mean±SEM | mean±SEM | mean±SEM | ASD vs control | asdMO vs ctrlMO | |

| (ASD-related) | ||||||

| ITGA2B | 4.68±0.92 | 8.47±0.94 | 5.62±2.35 | 9.64±1.93 | 4.0E-03* | 5.11E-03* |

| NRN1 | 3.53±0.40 | 5.41±0.59 | 3.92±0.58 | 6.65±0.85 | 2.2E-02* | 4.08E-02* |

| WDTC1 | 1.23±0.09 | 1.57±0.11 | 1.27±0.10 | 1.60±0.16 | 2.5E-02* | 3.50E-01 |

| PLCXD2 | 1.09±0.11 | 0.73±0.06 | 0.93±0.09 | 0.79±0.11 | 6.2E-03* | 6.01E-02 |

| UTS2 | 1.24±0.31 | 1.00±0.30 | 0.98±0.21 | 0.61±0.16 | 8.1E-02 | 4.55E-01 |

| KLHDC7A | 1.17±0.17 | 0.80±0.10 | 1.00±0.20 | 0.78±0.23 | 6.0E-01 | 4.89E-01 |

| LHB | 2.03±0.21 | 1.74±0.19 | 2.21±0.37 | 1.81±0.24 | 3.5E-01 | 3.82E-01 |

| LZTR2 | 0.68±0.68 | 0.55±0.54 | 1.03±1.03 | 0.76±0.76 | 6.3E-01 | 5.88E-01 |

| NUMBL | 0.72±0.07 | 0.90±0.14 | 1.17±0.21 | 1.17±0.29 | 8.1E-01 | 7.39E-01 |

| RKHD1 | 1.02±0.14 | 0.84±0.14 | 1.36±0.18 | 1.10±0.21 | 2.6E-01 | 1.38E-01 |

| SLC22A18AS | 4.53±0.49 | 4.65±0.46 | 3.79±0.40 | 5.32±0.84 | 6.9E-01 | 3.67E-01 |

| TAOK2 | 0.62±0.06 | 0.78±0.11 | 0.93±0.14 | 0.87±0.19 | 2.1E-01 | 3.84E-01 |

| UBL4A | 1.06±0.06 | 1.15±0.08 | 1.04±0.05 | 1.02±0.11 | 3.6E-01 | 4.46E-01 |

| NOVA2 | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | ||

| FAM124A | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | ||

| MYOG | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | ||

| (asdMO-related) | ||||||

| CSTA | 0.55±0.06 | 0.40±0.05 | 0.81±0.11 | 0.39±0.07 | 2.9E-02* | 3.45E-04* |

| CLEC2B | 0.88±0.06 | 0.68±0.12 | 1.50±0.14 | 0.88±0.13 | 1.5E-02* | 7.50E-04* |

| RPL34 | 0.71±0.06 | 0.51±0.10 | 1.07±0.13 | 0.63±0.12 | 8.8E-03* | 2.04E-03* |

| EEF1E1 | 0.49±0.05 | 0.34±0.06 | 0.58±0.05 | 0.38±0.07 | 5.5E-03* | 4.39E-03* |

| RPL9 | 0.50±0.07 | 0.34±0.08 | 0.68±0.09 | 0.42±0.12 | 1.0E-02* | 4.85E-03* |

| RPS3A | 0.51±0.05 | 0.35±0.06 | 0.64±0.07 | 0.40±0.09 | 3.7E-03* | 3.31E-03* |

| CES1 | 2.56±0.41 | 10.09±4.63 | 2.60±0.48 | 5.56±0.89 | 5.4E-03* | 6.88E-03* |

| ANK1 | 7.98±1.32 | 12.23±1.44 | 7.80±1.37 | 18.29±2.87 | 2.3E-02* | 5.88E-03* |

| BCL2A1 | 0.69±0.10 | 0.51±0.10 | 1.28±0.30 | 0.65±0.12 | 1.1E-01 | 1.26E-02* |

| RPS7 | 0.56±0.07 | 0.29±0.06 | 0.74±0.14 | 0.37±0.07 | 2.5E-03* | 7.73E-03* |

| SUB1 | 0.32±0.04 | 0.21±0.04 | 0.36±0.04 | 0.28±0.07 | 4.9E-03* | 3.06E-02* |

| TRIM58 | 5.92±0.77 | 9.71±1.11 | 6.42±1.37 | 12.41±2.36 | 1.4E-02* | 2.51E-02* |

| RPL39 | 0.72±0.17 | 0.38±0.09 | 0.77±0.13 | 0.52±0.14 | 2.4E-02* | 3.18E-02* |

| SPTB | 2.93±0.45 | 4.89±0.66 | 3.32±0.78 | 8.02±1.78 | 2.2E-02* | 2.98E-02* |

| UQCRB | 0.49±0.05 | 0.41±0.05 | 0.51±0.05 | 0.39±0.03 | 1.5E-01 | 1.98E-01 |

| PBX2 | 0.92±0.09 | 0.94±0.12 | 0.74±0.14 | 1.14±0.23 | 8.4E-01 | 6.46E-02 |

| SNRPG | 0.55±0.06 | 0.40±0.06 | 0.53±0.07 | 0.42±0.06 | 1.8E-02* | 2.75E-01 |

| NDUFA4 | 2.81±0.37 | 2.89±0.38 | 2.68±0.36 | 3.36±0.39 | 7.4E-01 | 9.06E-02 |

| (putativeASD-related) | ||||||

| FMR1 | 1.05±0.06 | 0.71±0.07 | 1.00±0.12 | 0.92±0.10 | 3.8E-03* | 7.13E-01 |

| MECP2 | 1.01±0.04 | 1.22±0.08 | 0.99±0.05 | 1.33±0.09 | 4.5E-02* | 3.47E-03* |

| SLC9A6 | 1.74±0.15 | 1.37±0.13 | 1.53±0.15 | 1.62±0.17 | 6.4E-02 | 4.88E-01 |

| UBE3A | 0.93±0.05 | 0.88±0.09 | 0.81±0.04 | 0.88±0.08 | 3.1E-01 | 6.50E-01 |

| MET | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | ||

| NRXN1 | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | u.d. | ||

p-value was calculated by t test using control (n = 21) and ASDs (n = 21), and ctrlASD (n = 21) and asdMO (n = 19).

*p<0.05.

Of the 16 ASD-associated genes, we could confirm significant changes in mRNA levels in only four genes (ITGA2B, NRN1, WDTC1, and PLCXD2). ITGA2B and NRN1 were also detected as significantly up-regulated in the asdMO group (Table 5). Changes in the other mRNA levels were not significant.

Of the measured 19 asdMO-associated genes, 14 genes (CSTA, CLEC2B, RPL34, EEFE1, RPL9, RPS3A, CES1, ANK1, BCL2A1, RPS7, SUB1, TRIM58, RPL39, and SPTB) were validated to significantly alter their mRNA levels. All genes except BCL2A1 also significantly changed their expression in the same direction in the ASD group (Table 5).

In addition to the 35 genes described above, we measured mRNA levels of six genes known as putative ASD-related genes based on the previous studies; FMR1, MET, MECP2, NRXN1, UBE3A, and SLC9A6 [25]. All these genes were not included in the 19 ASD-associated genes when identified using the 2-fold criterion, but MECP2, NRXN1, UBE3A, and SLC9A6 were included in the 496 ASD-associated genes, when the fold-change criterion was set at >1.5-fold. As shown in Table 5, MECP2 mRNA levels were found to elevate significantly in both the ASD and asdMO groups by qPCR, and FMR1 expression significantly reduced only in the ASD group, compared with the respective controls.

Discussion

Using a whole human genome microarray and the statistical analysis with 2-fold change criteria, we first identified the 19 genes differentially expressed in peripheral leukocytes between subjects with ASD and their age- and sex-matched controls. These ASD-associated genes were preferentially included in the network of cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, nerve system development and function. In addition, we identified the 57 genes whose mRNA levels were significantly different between unaffected mothers having children with ASD and mothers having children without any mental disorders. Differential expression of the 57 genes could be characterized as significant alterations of biosynthesis of protein and processing of ribosomal RNA. Intriguingly, unaffected mothers having children diagnosed with ASD possessed a unique gene expression signature, which could also be detected in the affected subjects with ASD, although the mothers having affected children and affected subjects had no direct heredity of blood between them.

Based on the twin and family studies, the etiology of autism has a substantial genetic component [25]. With genome-wide differential display approaches, a number of recent studies have highlighted SNPs, copy number variants (CNVs), and epigenetic factors in the dysregulated expression of candidate genes related to the occurrence of autism [26]. Putative and known candidates for susceptibility to autism are categorized to differentiation of neurons (e.g. DISC1, MET, PTEN, and ITGB3), neuronal cell adhesion (e.g. NRXN1, NLGN3, and NLGN4X), transmission of nervous system (e.g. OXTR, SLC6A4, GABRB3, and SHANK3), and regulation of neuronal activity (e.g. FMR1, MECP2, and UBE3A).

In addition to the known ASD-related genes (FMR1, MET, MECP2, NRXN1, UBE3A, and SLC9A6), we selected 36 genes from the 19 and 57 genes, and then validated changes in mRNA levels of 42 genes in total by qPCR. Finally, we found that expression of the 15 genes (ITGA2B, NRN1, CSTA, CLEC2B, RPL34, EEFE1, RPL9, RPS3A, CES1, ANK1, RPS7, SUB1, TRIM58, RPL39, and SPTB) was significantly changed to the same direction in both ASD subjects and women having ASD children (Table 5).

We observed that mRNA levels of ITGA2B encoding glycoprotein (GP) αIIβ were up-regulated about 2-fold in the peripheral leukocytes of the both ASD and asdMO groups (Table 5). GP αIIβ forms αIIbβ3 integrin with GP βIII encoded by ITGB3 [27]. ITGB3 is known as an autism-susceptible gene, which was identified as a male quantitative trait locus for whole blood serotonin levels [28]. αIIbβ3 integrin has an important role in the cell morphology, including synapse maturation. The increased expression of ITGA2B mRNA might modify cellular morphology of peripheral cells in mothers having children with ASD as well as subjects with ASD.

Another interesting observation was the reduction of SUB1 mRNA expression in ASD and asdMO groups. SUB1 encodes a transcription factor that activates RNA polymerase II transcription. A recent study has shown that SUB1 is also involved in the transcription of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase [29]. The significant down-regulation of SUB1 observed in our ASD subjects may be related to the reduction of MET protein reported in ASD cases [17], [18].

In addition to the important findings described above, validation of candidate genes by qPCR provided novel and unique gene expression changes in subjects with ASD and healthy women having ASD children. Interestingly, several genes encoding ribosomal proteins (RPL34, RPL9, RPS3A, RPS7, and RPL39) were all down-regulated in both ASD and asdMO groups. The ribosomal proteins play a crucial role in the regulation of protein synthesis; therefore, their expression must be strictly controlled [30]. Several lines of evidence have identified the linkage between ribosome biogenesis and diseases such as cancer, anemia, and aging. A recent review has also emphasized that protein synthesis is tightly linked to the regulation of neurological processes and cell growth [31]. The down-regulation of the genes encoding ribosomal proteins may indirectly reflect some atypical process of neurological development in subjects with ASD and also mothers having children with ASD.

qPCR also validated differential expression of two genes (MECP2 and fragile X mental retardation-1 (FMR1)), well-known candidates for susceptibility to autism, in ASD and/or asdMO group. The MECP2 gene encodes the X-linked methyl CpG binding protein 2 and its mutations and dysfunctions have also been associated with a broad array of other neurodevelopmental disorders including autism [32]. Consistent with increased expression of MECP2 in our study, several reports show that overexpression of MECP2 by gene duplication is a cause of neurodevelopmental delay in human clinical cases [33], [34]. Mutation in the MECP2 gene identical to some classical Rett syndrome mutations has been identified in small numbers of autistic phenotypes in females [35], [36]. Linkage analysis has identified the over- and undertransmittance of specific MECP2 variants in families with autistic children [37]. Taken together, these studies suggested a link between MECP2 and susceptibility to autism. The phenotypic differences between different clinical diagnoses may arise from differences in genetic background and environmental exposures in each affected individual. MECP2 may serve as a central epigenetic regulator of activity-dependent synaptic maturation.

The mutation of FMR1 triggers abnormal methylation, resulting in a loss of FMR1 expression in the lymphoblastoid cells in Fragile X syndrome, and such loss of FMR1 expression was also reported in the frontal cortex of postmortem brains from subjects with ASD [38]. In parallel with these findings, our subjects with ASD, but not unaffected mothers having affected children, showed significantly decreased FMR1 mRNA levels compared with their controls (Table 5). One might say that FMR1 may be involved in overt manifestations of ASD.

Although the underlying mechanism of autism is considered to be closely associated with brain maldevelopment, our results mentioned above suggest that the dysregulated expression of multiple candidate genes could be at least in part detectable in peripheral leukocytes. In fact, Hu et. al. demonstrated that the ASD-associated changes in gene expression involving in nervous system development could be detected in lymphoblastoid cell lines [39], [40]. Recent studies have suggested the possibility of identifying blood biomarkers by gene expression profiling studies in patients with mood disorders [41] and psychosis [42]. Moreover, Alter et. al. have shown autism- and increased paternal age-related changes in global levels of gene expression regulation in peripheral blood lymphocytes [43]. Thus, several lines of evidence suggest that gene expression signatures for neurodevelopmental disorders may be detectable in peripheral blood leukocytes. More recently, Voineagu et. al. have reported that the expression levels of neuronal specific splicing factor A2BP1 were dysregulated in the ASD brain [19]. The splicing of A2BP1-dependent alternative exons was also altered. However, in our cases, A2BP1 mRNA expression was not significantly changed in peripheral blood lymphocytes.

The implications of our approach suggest that several genes commonly found in both affected subjects and unaffected mothers having affected children might be potentially useful for understanding of mechanisms shaping the pathophysiology of ASD. Among our validated candidates, decreased expression of FMR1 [38] and increased expression of MECP2 [33] were already reported in lymphoblastoid cells and peripheral blood lymphocytes, respectively. However, the other candidate genes such as ITGA2B, SUB1, and ribosomal protein-related genes have not been documented. Identifying such genes could be helpful for objective diagnosis not solely relied on overt behavioral manifestations. The unique signatures observed in this study are informative to explore the genetic, epigenetic, and environmental background of ASD and might be a potential tool to find out the crucial factors-related to the overthreshold and subthreshold manifestations of ASD. To confirm these novel findings, we need more evidence established by case-case analysis and animal- and molecular-based studies. To show the predictive ability of the identified marker genes, a completely independent cohort study with larger numbers of subjects is currently underway.

Supporting Information

Experimental design for DNA microarrays.

(DOC)

TaqMan probe ID or sequences of primers for qRT-PCR analysis.

(DOC)

The list of overlapping genes between the ASD and asdMO group (fold-change > 1.5, vs. control or ctrlMO.

(XLS)

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported in part by grants from Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists B (10016093) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (to YK), and from Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research B (10003128) from the JSPS (to KR). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Folstein S, Rutter M. Genetic influences and infantile autism. Nature. 1977;265:726–728. doi: 10.1038/265726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steffenburg S, Gillberg C, Hellgren L, Andersson L, Gillberg IC, et al. A twin study of autism in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1989;30:405–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25:63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauritsen M, Ewald H. The genetics of autism. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:411–427. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton P, Macdonald H, Pickles A, Rios P, Goode S, et al. A case-control family history study of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35:877–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey A, Palferman S, Heavey L, Le Couteur A. Autism: the phenotype in relatives. J Autism Dev Disord. 1998;28:369–392. doi: 10.1023/a:1026048320785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belmonte MK, Cook EH, Jr, Anderson GM, Rubenstein JL, Greenough WT, et al. Autism as a disorder of neural information processing: directions for research and targets for therapy. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:646–663. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamain S, Betancur C, Quach H, Philippe A, Fellous M, et al. Linkage and association of the glutamate receptor 6 gene with autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:302–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin ER, Menold MM, Wolpert CM, Bass MP, Donnelly SL, et al. Analysis of linkage disequilibrium in gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit genes in autistic disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:43–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000207)96:1<43::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma DQ, Whitehead PL, Menold MM, Martin ER, Ashley-Koch AE, et al. Identification of significant association and gene-gene interaction of GABA receptor subunit genes in autism. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:377–388. doi: 10.1086/433195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talebizadeh Z, Lam DY, Theodoro MF, Bittel DC, Lushington GH, et al. Novel splice isoforms for NLGN3 and NLGN4 with possible implications in autism. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e21. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39:25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu VW, Frank BC, Heine S, Lee NH, Quackenbush J. Gene expression profiling of lymphoblastoid cell lines from monozygotic twins discordant in severity of autism reveals differential regulation of neurologically relevant genes. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wassink TH, Piven J, Vieland VJ, Huang J, Swiderski RE, et al. Evidence supporting WNT2 as an autism susceptibility gene. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:406–413. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingram JL, Stodgell CJ, Hyman SL, Figlewicz DA, Weitkamp LR, et al. Discovery of allelic variants of HOXA1 and HOXB1: genetic susceptibility to autism spectrum disorders. Teratology. 2000;62:393–405. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200012)62:6<393::AID-TERA6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szatmari P, Paterson AD, Zwaigenbaum L, Roberts W, Brian J, et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell DB, Sutcliffe JS, Ebert PJ, Militerni R, Bravaccio C, et al. A genetic variant that disrupts MET transcription is associated with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16834–16839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605296103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Judson MC, Bergman MY, Campbell DB, Eagleson KL, Levitt P. Dynamic gene and protein expression patterns of the autism-associated met receptor tyrosine kinase in the developing mouse forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:511–531. doi: 10.1002/cne.21969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voineagu I, Wang X, Johnston P, Lowe JK, Tian Y, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011;474:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron CA, Liu SY, Hicks C, Gregg JP. Utilization of lymphoblastoid cell lines as a system for the molecular modeling of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:973–982. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura Y, Martin CL, Vazquez-Lopez A, Spence SJ, Alvarez-Retuerto AI, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of lymphoblastoid cell lines distinguishes different forms of autism and reveals shared pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1682–1698. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamio Y, Wolf J, Fein D. Automatic processing of emotional faces in high-functioning pervasive developmental disorders: An affective priming study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurita H, Koyama T, Osada H. Autism-Spectrum Quotient-Japanese version and its short forms for screening normally intelligent persons with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:490–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe JS. Genetics. Insights into the pathogenesis of autism. Science. 2008;321:208–209. doi: 10.1126/science.1160555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bill BR, Geschwind DH. Genetic advances in autism: heterogeneity and convergence on shared pathways. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bray PF, Barsh G, Rosa JP, Luo XY, Magenis E, et al. Physical linkage of the genes for platelet membrane glycoproteins IIb and IIIa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8683–8687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss LA, Ober C, Cook EH., Jr ITGB3 shows genetic and expression interaction with SLC6A4. Hum Genet. 2006;120:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0196-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell DB, Li C, Sutcliffe JS, Persico AM, Levitt P. Genetic evidence implicating multiple genes in the MET receptor tyrosine kinase pathway in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2008;1:159–168. doi: 10.1002/aur.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caldarola S, De Stefano MC, Amaldi F, Loreni F. Synthesis and function of ribosomal proteins–fading models and new perspectives. FEBS J. 2009;276:3199–3210. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Twiss JL, Fainzilber M. Ribosomes in axons–scrounging from the neighbors? Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzales ML, LaSalle JM. The role of MeCP2 in brain development and neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Esch H, Bauters M, Ignatius J, Jansen M, Raynaud M, et al. Duplication of the MECP2 region is a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and progressive neurological symptoms in males. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:442–453. doi: 10.1086/444549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meins M, Lehmann J, Gerresheim F, Herchenbach J, Hagedorn M, et al. Submicroscopic duplication in Xq28 causes increased expression of the MECP2 gene in a boy with severe mental retardation and features of Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e12. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.023804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carney RM, Wolpert CM, Ravan SA, Shahbazian M, Ashley-Koch A, et al. Identification of MeCP2 mutations in a series of females with autistic disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(02)00624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zappella M, Meloni I, Longo I, Canitano R, Hayek G, et al. Study of MECP2 gene in Rett syndrome variants and autistic girls. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;119B:102–107. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loat CS, Curran S, Lewis CM, Duvall J, Geschwind D, et al. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 polymorphisms and vulnerability to autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:754–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Butler MG. Whole genome microarray analysis of gene expression in subjects with fragile X syndrome. Genet Med. 2007;9:464–472. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e3180ca9a9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu VW, Sarachana T, Kim KS, Nguyen A, Kulkarni S, et al. Gene expression profiling differentiates autism case-controls and phenotypic variants of autism spectrum disorders: evidence for circadian rhythm dysfunction in severe autism. Autism Res. 2009;2:78–97. doi: 10.1002/aur.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu VW, Nguyen A, Kim KS, Steinberg ME, Sarachana T, et al. Gene expression profiling of lymphoblasts from autistic and nonaffected sib pairs: altered pathways in neuronal development and steroid biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le-Niculescu H, Kurian SM, Yehyawi N, Dike C, Patel SD, et al. Identifying blood biomarkers for mood disorders using convergent functional genomics. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;2:156–74. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurian SM, Le-Niculescu H, Patel SD, Bertram D, Davis J, et al. I Identification of blood biomarkers for psychosis using convergent functional genomics. Mol Psychiatry. 2011. pp. 37–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Alter MD, Kharkar R, Ramsey KE, Craig DW, Melmed RD, et al. Autism and increased paternal age related changes in global levels of gene expression regulation. PLoS One. 2011;2:e16715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental design for DNA microarrays.

(DOC)

TaqMan probe ID or sequences of primers for qRT-PCR analysis.

(DOC)

The list of overlapping genes between the ASD and asdMO group (fold-change > 1.5, vs. control or ctrlMO.

(XLS)